Abstract

Additively manufactured Ni-base alloy IN625 suffered from intergranular oxidation (IGO) during air exposure at 900 °C. IGO is triggered by oxide buckling over the alloy’s grain boundaries (GBs), followed by oxidation of the open intergranular voids. Application of a 10 nm thick PVD coating of Ce induced a slower inward growth of the Cr2O3 scale, better oxide adherence and as a result strongly suppressed IGO. The main beneficial effect provided by Ce is improved oxide adherence preventing oxide buckling and oxidation of intergranular voids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to their optimum combination of superior mechanical properties and high corrosion resistance, Ni-base superalloys find numerous high-temperature applications in power generation, jet-engine technology, petrochemical industry, nuclear technologies, heat processing, etc1.

Additive manufacturing (AM) of Ni-base superalloys has been increasingly attracting attention, especially in the aeronautic branch, where AM of complex shaped components offers significant advantages2,3,4,5. Wrought Ni-base alloys IN718 and IN625 are commercially available Ni-base superalloys that are also widely studied in an AM context. The mechanical properties, primarily creep strength, of AM IN7186,7 and IN6258,9 are reported to be close to the baseline of their conventionally manufactured (CM) counterparts although a significant microstructural anisotropy is commonly reported. Additionally, the oxidation behavior of AM IN62510,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 and IN71823,24,25,26 has been extensively studied over the past decade resulting in three main observations systematically reported in the literature:

-

I.

In most case studies, oxidation rates for AM are 20-30% higher compared to CM.

-

II.

The anisotropic AM microstructure has minimal effect on the oxidation kinetics, i.e., no oxidation rate anisotropy in contrast to mechanical properties27,28,29.

-

III.

AM IN718 and IN625 suffer from severe intergranular oxidation (IGO), i.e., oxidation of metal grain boundaries.

In our previous publications13,14,30, AM IN625 was found to suffer from IGO attack, in agreement with most reported data in the literature10,11,12,15,17,18,19,20,22. Manipulations of the AM alloy microstructure, e.g., homogenization heat-treatment and recrystallization via hot-rolling, were demonstrated to have no effect on the oxidation morphology13. IGO was thus believed to occur in AM IN625 due to differences in chemical composition between AM and CM, e.g., a lower Si content in AM compared to CM14. However, the exact mechanism triggering IGO in AM Ni-base alloys is still actively debated in literature10,11,12,23,24,30, while more evidence is required to prove the batch-to-batch variation hypothesis.

Even though the nature of the IGO damage in AM Ni-base alloys is still not fully understood, available mitigation methods can be tested on existing materials to evaluate their potential efficiency. Rare-earth or reactive elements (REs) such as Y, Hf, La, Ce have been known to improve oxidation properties of both chromia- and alumina-forming high-temperature alloys31,32,33,34 for around 80 years. It is generally accepted that REs in chromia scales (a) lower the oxidation rate, (b) segregate to GBs in the oxide scale and suppress outward cation transport, and (c) improve scale adhesion. It is thus fathomable that REs may also suppress IGO of AM IN625, lowering the overall Cr consumption rate and thereby mitigating the enhanced outward Cr transport through the alloy grain boundaries (GBs) in AM alloy.

In the present work, the AM IN625 alloy batch studied in refs. 13,14 was PVD coated with 10 nm Ce and exposed in air for up to 1000 h at 900 °C. The obtained oxidation morphologies were compared with those on exposed uncoated AM IN625. The oxide scales were characterized with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDX), electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) and atom probe tomography (APT). The outcome of this work may lay ground for an industrial application of RE-coatings to AM materials and stimulate further research on the introduction of REs in the AM route.

Results

Effect of Ce on the oxidation of AM alloy IN625

Figure 1 shows the oxygen uptake by uncoated AM IN625 (circles) and Ce-coated AM IN625 (squares) after exposures at 900 °C in air. The Ce-coated material shows a markedly lower oxidation rate (~40%). Very similar mass changes were measured for the Y- and Z-cut specimens, which is consistent with previous reports in multiple studies for alloy 62513,14,21 and alloy 71823,24, where it was found that AM alloys do not demonstrate oxidation rate anisotropy in discontinuous long-term exposures.

The SEM micrographs in Fig. 2 demonstrate the temporal evolution of the oxide scale morphologies on uncoated and Ce-coated AM alloy IN625. The uncoated AM alloy demonstrates a characteristic oxidation morphology reported in our previous studies of this AM alloy batch13,14,30, as well as in other oxidation studies on AM IN62510,11,12,15,17,18.

The Cr2O3 scale grown on uncoated AM IN625 is prone to buckling. This mostly occurs over the alloy GBs and is already visible after 24 h. A hollow void forms underneath the buckled oxide. After longer oxidation times, the void is filled with newly grown Cr2O3 and appears as a compact ridge in the cross-section. The oxide ridge is accompanied by a network of elongated intergranular voids along the alloy GBs. After longer oxidation times, these voids are often filled with Cr2O3 and Al2O313. The intermetallic phase δ-Ni3Nb is enriched at the oxide metal interface, which is common for alloy 62535.

Applying a 10 nm Ce coating dramatically improves the oxidation behavior of the AM alloy: (i) the Cr2O3 scale appears thinner than on the exposed uncoated alloy; (ii) neither oxide buckling nor pronounced oxide ridges are observed although the Cr2O3 layer is convoluted; (iii) the occurrence of voids is essentially suppressed, which can be quantified in terms of the porosity depth, as well as the apparent volume fraction of the IG voids.

The effect of Ce on the growth kinetics of Cr2O3 on the alloy is illustrated in Fig. 3. Flat sections (away from alloy GBs) of the Cr2O3 scale were measured in SEM images and the oxide thickness is presented as a function of exposure time. Coating with Ce resulted in thinner Cr2O3 scales (see also Fig. 2). However, the immediate effect of Ce on the Cr2O3 thickness is weaker than the overall effect of Ce on the mass change (Fig. 1); approximately 20% vs 40% difference. This difference is attributed to the more extensive oxidation of voids in the uncoated case.

Determined from SEM images of uncoated (red circles) and Ce-coated (blue squares) AM alloy IN625 specimens exposed in air at 900 °C. Lines denote a power-law fit \({X}_{{{Cr}}_{2}{O}_{3}}={{kt}}^{n}\) with \({k}^{{AM}}\,\)= 1.4 × 10−8 m s−0.4 and \(n=\,\)0.4 for uncoated alloy as well as \({k}^{{AM}-{Ce}}\,\)= 2.5 × 10−9 m s−0.5 and \(n=\,\)0.5 for Ce-coated AM alloy IN625.

The strongest effect of Ce is found for the observed depth of porosity (Fig. 4), which is a factor of two lower in the Ce-coated specimens of AM IN625, as compared to the uncoated AM material.

Determined from SEM images of uncoated (circles) and Ce-coated (squares) AM alloy IN625 exposed in air for up to 1000 h at 900 °C. Lines denote parabolic fits with \({k}_{p}^{{void},{AM}}\,\)= 3.6 × 10−16 m2 s−1 for uncoated and \({k}_{p}^{{void},{AM}-{Ce}}\,\)= 7.3 × 10−17 m2 s−1 for Ce-coated AM alloy IN625.

Figure 5 shows Cr concentration profiles measured with EDS in uncoated (circles) and Ce-coated (squares) AM alloy IN625. The Cr-depletion profiles are similar for the longitudinally (Y-cut) and transversally (Z-cut) sectioned specimens. The interface Cr concentration in uncoated AM IN625 is 15 wt%, which has also been reported for CM IN625 exposed in air at 900 °C36. Applying Ce to AM IN625 resulted in a higher Cr-interface concentration, 18 wt%, as well as a shallower Cr-depletion zone: 60 μm in the Ce-coated specimen compared to 80 μm in the uncoated AM IN625. Integration of depletion profiles, as described e.g., in ref. 37, allows determining a cumulative Cr loss due to selective oxidation of Cr and yields 3.4 and 1.7 mg/cm2 for uncoated and Ce-coated alloy, respectively. The corresponding oxygen uptakes are 1.56 and 0.78 mg/cm2, the latter numbers agreeing well with the experimentally measured mass gains in Fig. 1.

Ce-doping and microstructure of Cr2O3 scales

The SEM BSE images in Fig. 6 show the oxide scale grown on uncoated (Fig. 6a,b) and Ce-coated (Fig. 6c, d) specimens of AM IN625 after 1000 h air oxidation at 900 °C. On the uncoated alloy, thick and dense oxide ridges are visible over the GBs in the alloy. Apart from the elongated IG voids, spherical Kirkendall voids can be seen within the grains underneath the oxide scale. The Cr2O3 scales grown on the Ce-coated specimens are thinner and did not produce massive oxide ridges above alloy GBs. The void occurrence in the alloy subsurface is shallower and less intense in this case.

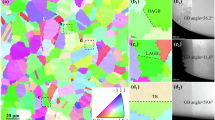

The EBSD maps in Fig. 7 illustrating the grain structure of the Cr2O3 scales shown in Fig. 6 demonstrate that on uncoated AM IN625 (Fig. 7a, b) Cr2O3 grows outwards, i.e., the smaller Cr2O3 grains are located at the oxide-metal interface while the larger Cr2O3 grains are located in the outer part of the scale. Small grains of the newly formed Cr2O3 can be seen in the bulk of the oxide ridges in the immediate vicinity of the oxide-metal interface and the corresponding GB. The latter is an indication of healing of the void underneath the Cr2O3 layer buckled over the alloy GB.

After 1000 h exposure, the IG voids are filled with Cr2O3 as previously reported in refs. 13, 30. The δ-Ni3Nb phase precipitated at the oxide-metal interface, as well as in the IG voids along GBs, but not in the spherical in-grain pores.

In contrast to the uncoated AM alloy, in the Ce-coated specimens Cr2O3 apparently grew inwards (Fig. 7c, d) as there are smaller Cr2O3 grains in the outer part of the Ce-doped scale, at the gas-oxide interface, while larger grains can be seen at the bottom of the oxide film. In addition to the changed oxide growth direction, the Ce-doped Cr2O3 is more adherent and reveals no signs of oxide delamination and re-healing. Underneath the tightly adherent outer oxide scale, the elongated IG voids do not contain any Cr2O3. Finally, the δ-Ni3Nb phase segregated to the oxide-metal interface, with IG voids at the GBs in the alloy subsurface. The black continuous layer between the Cr2O3 and the metal (δ-Ni3Nb and FCC-Ni) in Fig. 7 is a specimen preparation artifact. Polishing with colloidal silica etches the metal faster than Cr2O3 creating a step that appears black in EBSD maps.

Figure 8 shows SEM EDS maps for uncoated and Ce-coated AM IN625. The elongated voids underneath the oxide scale grown on both specimens contain oxide. The uncoated specimens reveal both Cr and Al enrichment in the voids, while the voids in the Ce-coated alloy do not contain Cr. This additionally confirms that the application of Ce prevents the voids from opening due to increased oxide adhesion to the metal, which is a well-known consequence of RE doping (compare also oxide ridges in coated and uncoated specimens in Fig. 2), hindering oxidation of Cr by the incoming gas from the atmosphere. With the Ce coating the voids are isolated from the atmosphere and contain exclusively Al2O3 formed due to internal oxidation (Fig. 7c, d).

Tracing Ce at Cr2O3 grain boundaries

Figure 9 shows SEM SE images of oxidized surfaces of uncoated (a) and Ce-coated (b) AM alloy IN625 after 24 h of air oxidation at 900 °C. Massive oxide ridges protrude above the GBs of the uncoated AM alloy. Oxide ridges on the Ce-coated alloy surface are less pronounced. For more details, TEM lamellas were sampled across ridges in both specimens.

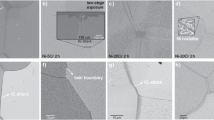

Figure 10 displays BF and HAADF TEM images of the Cr2O3 scale thermally grown on uncoated alloy after 24 h in air at 900 °C. The oxide scale is around 1.2 μm thick. The average grain size of Cr2O3 in the outer part of the scale is approximately 200 nm, decreasing to tens of nm towards the bottom of the scale. The scale contains small (10–20 nm) bright inclusions in the inner part close to the metal-oxide interface (Fig. 10a). EELS analysis of these inclusions (Fig. 11) shows that the particles are primarily rich in Ni, as Ni L is the only large edge, in addition to the O K and Cr L edges.

Figure 12 shows BF and HAADF STEM images of the Cr2O3 scale grown on the Ce-coated AM IN625 after 24 h in air at 900 °C. Application of Ce resulted in a thinner scale (0.6 μm) and grain refinement of the oxide. The average grain size of Cr2O3 in the Ce-doped scale is approximately 40 nm and does not vary through the scale thickness.

Figure 13a shows HAADF STEM image of the Cr2O3 scale grown after 24 h air exposure at 900 °C (Fig. 12) along with an EELS spectrum from Fig. 13a, highlighting the presence of Ce (Fig. 13b) and a linescan across a Cr2O3 GB (Fig. 13c), demonstrating a Ce-enrichment.

Chemistry of Cr2O3 grain boundaries

The Ce-enrichment at the oxide GBs is further confirmed by APT. Reconstructions of APT data collected from the Cr2O3 scale grown after 1000 h air exposure at 900 °C are presented in Fig. 14 and Fig. 15 for uncoated AM IN625 and Ce-coated AM IN625, respectively. From these images, it is possible to determine that the Cr2O3 scale grown on the uncoated material contains significant amounts of most alloying elements, both at GBs and in the grain interior. Among these elements, Ti, Al, Si and Nb appear to segregate preferentially at GBs. Ni, Ti and Al seem to preferentially enrich specific grains and regions, which may indicate that these segregations emerged during the initial transient oxidation stage as explained e.g., in ref. 38.

Cr2O3 scales were grown on uncoated AM IN625 after 1000 h air exposure at 900 °C. Box A shows an overview of the full run, while box B shows Ni, Al, Ti, and Si plotted separately. The arrow indicates the location and direction of the 1D composition profile across the oxide grain boundary, shown in Fig. 16.

Cr2O3 scale grown on Ce-coated AM IN625 after 1000 h air exposure at 900 °C. Box A shows an overview of the full run, while box B shows Ni, Al, Ti, Si, and Ce plotted separately. The arrow indicates the location and direction of the 1D composition profile across the grain boundary shown in Fig. 16.

Ni can be also found forming particles in the 3–15 nm size range with total compositions around 60 at% Ni, 15 at% Cr, 25 at% O. Interestingly, these Ni-rich particles were not found in the Ce-doped Cr2O3 (Fig. 12 and Fig. 15). The most plausible explanation of their origin is the transient oxidation stage during which all alloy elements oxidize on the alloy surface. Once the protective oxidation regime is established, the NiO particles were occluded in the Cr2O3 grains and further reduced to pure nickel due to the low oxygen potential at the NiO/Cr2O3 boundaries. According to Whittle and Stringer31 REs shorten the transient stage and promote the transition to the selective oxidation regime. This would explain the much cleaner Cr2O3 scales observed for the Ce-coated alloy.

Quantitative composition profiles across oxide GBs and the interface between the oxide matrix and Ni-particles are plotted in Fig. 16. A significant difference is obvious when comparing the uncoated AM IN625 Cr2O3 scale with the scale obtained under identical conditions on the Ce-coated AM IN625. In the Ce-coated specimen, very little impurities can be measured both at GBs and inside the grains. Ni-particles are virtually absent, with only very small signs of Ni clustering around the GB triple point region. Small amounts of Ti and Al can be found doping different oxide grains, but their concentration is more homogeneous across the measured volume. Most importantly, significantly lower enrichment of Ti, Al, Si and Nb can be found at GBs where Ce accumulates instead.

Cr2O3 scales were grown on uncoated (AM) and Ce-coated (Ce-AM) AM alloy IN625 exposed for 1000 h in air at 900 °C. a Main segregating elements in GB of Cr2O3 on AM, b trace elements found in GB of Cr2O3 on AM. c Main segregating elements in GB of Ce-doped Cr2O3 on Ce-AM, d trace elements found in GB of Ce-doped Cr2O3 on Ce-AM. Proxigram across Ni-isosurface (3.5 at.%) found in the Cr2O3 grown on AM IN625 (e).

Discussion

The oxidation kinetics of CM and AM alloy IN625 has been recently analyzed and reviewed by Chyrkin et al.30. Thickening of the flat and unwrinkled Cr2O3 scale was demonstrated to be independent of the alloy substrate (CM or AM) and to be sub-parabolic. The slowing down of the oxide thickening over time is related to the grain size distribution in the scale. The Cr2O3 scales shown in Fig. 7a, b and Fig. 10 demonstrate that the Cr2O3 grain size gradually increases from the oxide-metal towards the oxide-gas interface. The sub-parabolic oxidation kinetics is well-documented for slowly growing α-Al2O3-scales in which transport is governed by inward diffusion of oxygen via oxide GBs. The columnar grains in the Al2O3 scale are wider at the bottom of the oxide scale. The GB density decreasing over time leads to a slower oxide growth39. A similar mechanism prevails in Cr2O3 at 700-900 °C, i.e., the outward diffusion of Cr cations is the dominating transport mode in air-grown Cr2O3 scales40, which makes the oxide growth kinetics sensitive to the GB density and, hence, the grain size distribution in the scale.

In the present study, Cr2O3 scaling on the uncoated AM alloy IN625 is also sub-parabolic Fig. 3. Application of the Ce-coating resulted in a more homogeneous grain distribution (Fig. 12) and the parabolic scaling kinetics prevails for up to 300 h. Further thickening of the Cr2O3 scale resulted in larger grains in the inner part of the scale after 1000 h (Fig. 7c, d) and some deceleration of the scaling process (see sub-parabolic fits in Fig. 3). However, the overall oxide growth kinetics for the Ce-coated alloy was much closer to the parabolic time-law than that for the uncoated alloy. Further beneficial effects of coating with Ce will be discussed below.

IGO is common for chromia-forming AM Ni-base alloys and has been reported for IN62510,11,12,13,14,15,17,18,22, IN71823,24,25 and other AM Ni-base alloys41,42,43. IGO is a complex phenomenon involving (i) oxide buckling over the alloy GBs and formation of oxide ridges, (ii) formation of voids in the alloy subsurface, (iii) internal oxidation of alloy components with a higher affinity for oxygen than Cr, e.g., Mn, Ti, Al, Si, (iv) oxidation of open intergranular voids after oxide cracking and/or spallation.

The relevance of these phenomena for IGO as well as the current hypotheses explaining the occurrence of IGO in AM alloys were assessed by de Leon Nope et al.12: (i) grain boundary misorientation44,45, (ii) minor differences in chemical composition of CM and AM13,14, (iii) void formation16,23,24. Both spherical and elongated voids are interpreted as Kirkendall effect46 arising from a supersaturation of vacancies due to a mismatch of Cr- and Ni-flux induced by the Cr-depletion47. These vacancies tend to condense at available interfaces, i.e., (i) oxide/metal interface, (ii) alloy GBs and (iii) internal precipitates. The authors12 believe that the void formation and thus IGO is promoted by internal oxidation and excess interstitially dissolved oxygen resulting from the atomizing process.

In the present study, the microstructural evolution of the oxide scale on the uncoated AM alloy in Fig. 2 allows reconstructing the timeline of these events and summarize the IGO mechanism in Fig. 17:

-

a.

Oxide growth and formation of voids. The voids appear in the early stages of the Cr2O3 scale growth, as demonstrated already after 2 h exposures in ref. 13. It is evident that the void formation is related to oxidation-induced Cr-depletion. Based on the available literature, voids are inevitable in AM alloys such as IN625.

-

b.

Oxide delamination/buckling comprises the second important step in the IGO mechanism. Thermally grown Cr2O3 is known to be under compressive stresses because the molar volume of the oxide is twice as high as that of the consumed metal48,49. These stresses can be dissipated through oxide delamination, wrinkling, buckling, blistering, as e.g., reported for Cr2O3 grown on Fe-28Cr50 or even pure Cr40. Remarkably, the Cr2O3 scale buckles primarily over the alloy GBs, where oxide adhesion seems to be the weakest and/or metal creep deformation is easier (see Fig. 2 and Fig. 9). The underlying void is eventually filled with the newly grown Cr2O3 as evidenced by finer grains in the oxide formed underneath the buckled layer in Fig. 7a, b. This local re-healing intensifies Cr-depletion underneath the buckled oxide and promotes further void formation, oxide growth along the underlying GB and increases thereby local stresses.

-

c.

Voids open and oxidize. Apart from oxide buckling, the stresses in the oxide scale can be relieved via creep and plastic deformation of the underlying alloy. Application of external mechanical loads is demonstrated to exacerbate IGO11 through opening the IG voids and letting them oxidize.

From this perspective, the key trigger of IGO occurring in AM alloys is poorer adherence of Cr2O3 to the alloy substrate compared to CM. Impairment of adhesion may have various reasons: (i) a different chemical composition of the AM alloy batch, namely, lower concentrations of minor elements with high affinity to oxygen, such as Mn, Ti, Al, Si14. Minor precipitations of SiO2 and Al2O3 at the scale-alloy interface may act as anchors and pegs increasing oxide adherence31,51; (ii) higher concentration of interstitial oxygen and nitrogen due to AM process may have a similar effect reported for carbon and sulfur in FeCrAl-base alloys33, although this effect seems to be less relevant for Cr2O333; (iii) higher density of dislocations in the AM material, i.e., the main source of IG porosity, may also aggravate a supersaturation of vacancies injected at the oxide metal interface, resulting in poorer adherence and oxide delamination under compressive stresses47.

It should be noted though that the exact mechanism of oxide delamination, as well as the effect of AM on adherence of oxide scales thermally grown on AM high-temperature alloys, is not understood yet and goes far beyond the scope of the present study. Dedicated experiments tracing the exact chemical compositions and metallurgical states, e.g., grain size/orientation, density of dislocations, etc., should be carried out to identify and clarify these effects. Another important reservation to be made is that the proposed IGO mechanism applies only to oxidation in air or oxygen. It is well-known that intergranular attack can occur without any oxide delamination and mechanical ingress of oxygen. IGO may be triggered by more corrosive species than molecular oxygen such as H2O, CO2, SO2, etc. 52,53,54,55,56.

The effect of Ce on the oxidation behavior of a binary Ni-Cr alloy was explored through alloying NiCr with Ce as early as in the pioneering work patented by Pfeil in 193757. Starting from the late 1960s, the RE effect has been intensely explored and summarized in numerous fundamental reviews31,32,33,58,59,60. The RE addition to the alloy can be technically achieved in different ways. RE can be added during the metallurgical process as a metallic addition61. The RE can also be added as an oxide dispersion in a powder metallurgical route, so-called mechanical alloying62. It is also possible to apply an RE to the alloy surface without alloying via an ion implantation process or as PVD-coatings, which was demonstrated for ferritic stainless steels for application as interconnects in solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) stacks63,64.

In the present work, the 10 nm Ce-coating applied to AM IN625 was expected to improve the overall oxidation resistance. Four main phenomena characteristic for the RE effect in Cr2O3 were detected:

-

I.

Reduced growth rate of the chromia scale. The oxide thickness measured on the flat sections of the scale over the larger alloy grains indicated a lowering of the oxide scale thickness after the application of Ce (Fig. 3).

-

II.

The transport mechanism through the Cr2O3 scale is changed from predominantly outward Cr transport (without Ce addition) to inward oxygen transport on the Ce-coated specimens Fig. 7.

-

III.

The resistance of the scale to buckling is significantly improved.

-

IV.

Reduced growth stresses in the Ce-doped Cr2O3 scale (less oxide rumpling, see Fig. 2) resulting in no ruptures of the underlying metal.

All four mentioned phenomena may in principle be correlated with the change in the scale growth mechanism by RE-addition suppressing outward cation diffusion, as discussed by Quadakkers et al.65 based on oxygen tracer experiments. The latter authors suggested that the change from combined outward metal/inward oxygen transport to predominantly inward oxygen diffusion would substantially reduce the growth stresses (thereby reducing scale buckling), not only by reducing the volume of oxide formed per unit surface area per second, but also by avoiding formation of new oxide within the pre-formed scale. In addition, oxide scales grown by inward oxygen transport were claimed to generate reduced vacancy injection to the oxide/metal interface, thus explaining the improved scale adhesion.

Interestingly, the application of a Ce coating had a relatively moderate effect on the oxide growth rate, i.e., a factor of 2 after 24 h and 1.3 after 1000 h (Fig. 3), whereas Ce ion implantation in a binary model alloy Ni-20Cr66 resulted in a much stronger (a factor of 5–6) reduction of the oxidation rate during air oxidation at 1000 °C. An even stronger effect of the Ce-coating amounting to an order of magnitude was found for Cr2O3 growing on a binary model Fe-18Cr alloy in H2/H2O at 900 °C67. At the same time, Ce-coatings applied to commercial steels68 also demonstrate a moderate effect not exceeding a factor of 2. Such a big difference between commercial and model alloys can be explained by segregation of alloy constituents to the GBs of the growing Cr2O3 scale. The APT maps in Fig. 15 demonstrate segregations of literally all elements from the alloy at the sampled GB in the oxide. Similar APT results were reported for Cr2O3 grown on a Fe-22%Cr steel69. These segregation of e.g., Ti, Mn, Si, etc. apparently play their own role in impeding the outward transport of Cr cations along the GBs in the Cr2O3 scale. It is thus reasonable to assume that a RE effect based on the segregation of the RE to the oxide GBs should be stronger on “cleaner” model alloys than on commercial alloys and steels.

The occurrence of intergranular voids was suppressed by the following beneficial effects of the Ce-coating: (i) a reduced scaling rate resulted in a lower Cr flux within the alloy towards the oxide-metal interface (Fig. 5); (ii) a better oxide adhesion prevented the oxide scale from buckling and decohesion thereby suppressing initiation of the interfacial voids; (Fig. 7c, d); (iii) reduced ruptures along the GBs in the underlying metal due to lower growth stresses in the Ce-doped Cr2O3.

Application of Ce did not completely suppress the voids in the AM specimens (Fig. 6c, d). Apparently, the subsurface oxidation-induced Kirkendall voids are an inevitable intrinsic feature of the AM high-temperature alloys with the characteristic deficient microstructures. However, an improvement with respect to IGO can be achieved through a better oxide adherence (Fig. 1), which prevents the IG voids from oxidation attack by gas penetration through the cracks in the buckled Cr2O3.

In light of the above findings, the question arises whether RE additions can be used in AM materials to avoid IGO. The coating approach used here clearly proves effective, but requires an extra processing step, hence adding RE to the alloy is a more attractive approach. The challenge when it comes to RE alloy additions in AM is that RE are high oxygen affinity elements and their oxides possess very low dissociation pressures. Therefore, powders pre-alloyed with RE, such as Y, will likely be converted into RE-rich oxides, such as Y2O3 or Y3Al5O12 (YAG), during the AM step70. This is not necessarily problematic, as RE-oxide additions have proven to also show a beneficial effect on oxidation: Quadakkers et al.65,71 used isotope tracers to study the oxidation mechanism of wrought Ni-25Cr and with MA754 (which includes Y2O3 additions). Due to the Y2O3 addition (0.5 wt%), MA754 alloy formed a single-phase Cr2O3 scale and exhibited much better oxidation performance with improved oxide adhesion and slow oxide growth rate. In fact, besides their beneficial effect on oxidation properties, RE oxide additions (Y2O3) are used to improve the mechanical properties, especially creep resistance72. When it comes to AM-produced alloys, the literature on the effect of RE additions focuses mostly on improving the mechanical properties73,74. Oxidation studies of such alloys are limited and mainly carried out on Al2O3 forming alloys75,76,77. In summary, it is not unreasonable to expect that RE-oxide additions can effectively mitigate IGO in a similar way as presented here by a Ce coating. However, this remains unknown at the moment, and further experimental work is needed to confirm this.

Methods

Materials

Cubes of AM IN625 measuring 15 × 15 × 15 mm3 were additively manufactured by Powder Bed Fusion-Laser Beam (PBF-LB) and provided by Siemens Energy AB (Finspång, Sweden) in the as-received condition. To analyze the microstructural anisotropy of the obtained AM material, the AM IN625 cubes were sectioned in 2 directions: parallel (AM-X and AM-Y) and perpendicular (AM-Z) to the build axis. As no differences between the longitudinal X and Y cuts were detected, both parallel to the build direction, hereinafter only AM-Y is compared with the transversal AM-Z cut. The chemical composition of AM IN625 obtained by ICP-OES is given in Table 1. The alloy coupons of AM IN625 were machined to 15 × 15 × 2 mm3 dimensions. The surfaces were ground with SiC papers and polished down to 0.25 µm with diamond pastes. A set of mirror-polished coupons was PVD coated with 10 nm Ce by Alleima AB (Sandviken, Sweden).

Exposures

Discontinuous exposures were performed in tube furnaces (⌀ 44 mm) at 900 °C in stagnant lab air for up to 1000 h. The specimens were degreased in ethanol and acetone prior to exposure and directly introduced into the hot zone of the tube furnace. The temperature calibration was performed by an external Pt/Rh-thermocouple placed next to the specimens. The specimens were removed from the hot zone of the furnace and cooled down in air for weighing. The specimens were re-introduced into the hot zone to continue the exposure after every weighing step. Selected specimens, e.g., 72, 168, and 300 h, were exposed isothermally, i.e., without intermediate cooling. As no measurable difference between the isothermal and discontinuous mass change could be detected, oxide spallation was ruled out.

After exposures, the specimens were removed from the hot zone of the furnace. The mass gain curves were obtained by gravimetric measurements prior and after the exposures using Mettler Toledo XP6 microbalance with a 1 µg resolution.

Microstructural characterization

EBSD maps were obtained using a Zeiss Ultra 55 field emission gun (FEG) SEM equipped with an HKL Channel 5 EBSD detector. EBSD maps of the as-received material can be found in ref. 30. An FEI Quanta 200 SEM equipped with an Oxford X-Max 80 energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) was employed for pre- and post-exposure analysis. Aztec software was used to evaluate the EDS data. Cross-sections were made on exposed samples by the broad-ion beam (BIB) technique using a Leica EM TIC 3X, as well as by conventional polishing with diamond pastes (0.25 µm) and colloidal silica (≈50 nm) after hot-mounting into conductive mounting resin Polyfast (Struers, Denmark). The specimens were gold-sputtered and electroplated with nickel prior to hot-mounting.

Focused ion beam/scanning electron microscopy, FIB/SEM

An FEI Versa 3D combined Focused Ion Beam/SEM (FIB/SEM) workstation was used to produce cross-section thin foils from the oxide scale and subjacent metal. In order to protect the oxidized surface during the subsequent ion milling, a thin Pt layer was first deposited with the aid of electrons on the surface (25 × 5 μm2) and then a thicker Pt layer (with a thickness of ∼2 μm) was deposited on top using Ga-ions. At the initial stages of the milling, higher ion currents were used, while lower currents were chosen at the final stages to produce finer surfaces. Lower ion energies (2 and 5 kV with ion currents of 49 and 27 nA, respectively) were selected in the final stages of polishing to minimize the potential artifacts from FIB milling.

Scanning transmission electron microscopy, STEM

Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) was performed using an FEI Titan 80-300 TEM/STEM equipped with an Oxford Instruments EDS detector and a FEG to acquire STEM micrographs in High Angle Annular Dark Field (HAADF) and Bright Field (BF) modes as well as to obtain EELS.

Atom probe tomography

An FEI Versa 3D dual-beam FIB–SEM workstation was used to prepare samples for APT. The APT samples were taken from the fine-grain areas to ensure the analysis of the oxide GBs. The well-established in situ lift-out specimen preparation of APT tips was employed78. The atom probe measurements were performed using a local electrode atom probe CAMECA LEAP 6000 XR. The instrument was used in laser pulse mode at 40 K specimen temperature, 0.5–1.0% evaporation rate, and 50 pJ laser energy. Auto pulse frequency control was implemented and set to guarantee a minimum mass spectrum range of 180 Da. CAMECA APT Suite 6 reconstruction software was used to analyze the obtained APT data.

Data availability

All data that support the results of the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Reed, R. C. The Superalloys. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511541285 (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Murr, L. E. Metallurgy of additive manufacturing: examples from electron beam melting. Addit. Manuf. 5, 40–53 (2015).

Frazier, W. E. Metal additive manufacturing: a review. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 23, 1917–1928 (2014).

DebRoy, T. et al. Additive manufacturing of metallic components—process, structure and properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 92, 112–224 (2018).

Karmuhilan, M. & Kumanan, S. A review on additive manufacturing processes of Inconel 625. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 31, 2583–2592 (2022).

Sanchez, S. et al. The creep behaviour of nickel alloy 718 manufactured by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Des. 204, 109647 (2021).

Kassner, M. E., Son, K. T., Lee, K. A., Kang, T.-H. & Ermagan, R. The creep and fracture behavior of additively manufactured Inconel 625 and 718. Mater. High. Temp. 39, 499–506 (2022).

Son, K., Kassner, M. E. & Lee, K. A. The creep behavior of additively manufactured Inconel 625. Adv. Eng. Mater. 22, 1900543 (2020).

Son, K.-T. et al. The creep and fracture properties of additively manufactured Inconel 625. Materialia 15, 101021 (2021).

de Leon Nope, G., Wang, G., Alvarado-Orozco, J. M. & Gleeson, B. Role of elemental segregation on the oxidation behavior of additively manufactured alloy 625. JOM 74, 1698–1706 (2022).

de Leon Nope, G., Wang, G., Alvarado-Orozco, J. M. & Gleeson, B. Effects of High-temperature oxidation on fatigue life of additive-manufactured alloy 625. Miner., Met. Mater. Ser. 249, 269 (2023).

de Leon Nope, G., Wang, G. & Gleeson, B. Influence of alloy 625 manufacturing process on 950 °C oxidation behavior in air and post-oxidation high-cycle fatigue performance. High. Temp. Corros. Mater. 1, 13 (2024).

Chyrkin, A. et al. High-temperature oxidation behavior of additively manufactured IN625: Effect of microstructure and grain size. Corros. Sci. 205, 110382 (2022).

Chyrkin, A. et al. Intergranular oxidation of additively manufactured Ni-base alloy 625: the role of Si. Corros. Sci. 219, 111234 (2023).

Parizia, S. et al. Effect of heat treatment on microstructure and oxidation properties of Inconel 625 processed by LPBF. J. Alloy. Compd. 846, 156418 (2020).

Ramenatte, N. et al. A comparison of the high-temperature oxidation behaviour of conventional wrought and laser beam melted Inconel 625. Corros. Sci. 164, 108347 (2020).

Pineda-Arriaga, K. Y. et al. Oxidation in water vapor of Inconel 625 fabricated by additive manufacturing. High. Temp. Corros. Mater. 101, 1–11 (2024).

Pineda-Arriaga, K. Y. et al. Characterization of the high-temperature oxidation behavior of Inconel 625® fabricated by additive manufacturing and conventional methods. Oxid. Met. 98, 489–510 (2022).

Condruz, M. R., Matache, G., Paraschiv, A., Badea, T. & Badilita, V. High temperature oxidation behavior of selective laser melting manufactured IN625. Metals 10, 668 (2020).

Sharifitabar, M., Khorshahian, S., Shafiee Afarani, M., Kumar, P. & Jain, N. K. High-temperature oxidation performance of Inconel 625 superalloy fabricated by wire arc additive manufacturing. Corros. Sci. 197, 110087 (2022).

Lewis, E. R. et al. Microstructural characterisation and high-temperature oxidation of laser powder bed fusion processed Inconel 625. Mater. Lett. 311, 131582 (2022).

Andrade, B. W., Mariani, F. E., Coelho, R. T. & de Sousa Malafaia, A. M. Comparison of the oxidation behavior at high temperature of INCONEL 625 forged and produced by additive manufacturing. High. Temp. Corros. Mater. 1, 14 (2024).

Sanviemvongsak, T., Monceau, D., Desgranges, C. & Macquaire, B. Intergranular oxidation of Ni-base alloy 718 with a focus on additive manufacturing. Corros. Sci. 170, 108684 (2020).

Sanviemvongsak, T., Monceau, D. & Macquaire, B. High temperature oxidation of IN 718 manufactured by laser beam melting and electron beam melting: effect of surface topography. Corros. Sci. 141, 127–145 (2018).

Sanviemvongsak, T. et al. Cyclic oxidation of alloy 718 produced by additive manufacturing compared to a wrought-718 alloy. Corros. Sci. 192, 109804 (2021).

Calandri, M. et al. Solution treatment study of Inconel 718 produced by SLM additive technique in view of the oxidation resistance. Adv. Eng. Mater. 20, 1800351 (2018).

Kunze, K., Etter, T., Grässlin, J. & Shklover, V. Texture, anisotropy in microstructure and mechanical properties of IN738LC alloy processed by selective laser melting (SLM). Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 620, 213–222 (2015).

Rezaei, A. et al. Microstructural and mechanical anisotropy of selective laser melted IN718 superalloy at room and high temperatures using small punch test. Mater. Charact. 162, 110200 (2020).

Pleass, C. & Jothi, S. Influence of powder characteristics and additive manufacturing process parameters on the microstructure and mechanical behaviour of Inconel 625 fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Addit. Manuf. 24, 419–431 (2018).

Chyrkin, A. et al. Oxidation of additively manufactured Ni-base alloy IN625: mechanism of intergranular oxidation. Corros. Sci. 256, 113218 (2025).

Whittle, D. P. & Stringer, J. Improvements in high temperature oxidation resistance by additions of reactive elements or oxide dispersions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 295, 309–329 (1980).

Hou, P. Y. & Stringer, J. The effect of reactive element additions on the selective oxidation, growth and adhesion of chromia scales. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 202, 1–10 (1995).

Pint, B. A. Progress in understanding the reactive element effect since the Whittle and Stringer literature review. John Stringer Symp. High. Temp. Corros. 9, 19 (2001).

Quadakkers, J. & Singheiser, L. Practical aspects of the reactive element effect. Mater. Sci. Forum 369–372, 77–92 (2001).

Chyrkin, A., Huczkowski, P., Shemet, V., Singheiser, L. & Quadakkers, W. J. Sub-scale depletion and enrichment processes during high temperature oxidation of the nickel base alloy 625 in the temperature range 900–1000 °C. Oxid. Met. 75, 143–166 (2011).

Huczkowski, P. et al. Effect of gas flow rate on oxidation behaviour of alloy 625 in wet air in the temperature range 900–1000 °C. Mater. Corros. 68, 159–170 (2017).

Chyrkin, A. et al. Modelling compositional changes in nickel base alloy 602 CA during high temperature oxidation. Mater. High Temp. 32, 102–112 (2015).

Vayyala, A. et al. A nanoscale study of thermally grown chromia on high-Cr ferritic steels and associated oxidation mechanisms. J. Electrochem. Soc. 167, 061502 (2020).

Naumenko, D., Gleeson, B., Wessel, E., Singheiser, L. & Quadakkers, W. J. Correlation between the microstructure, growth mechanism, and growth kinetics of alumina scales on a FeCrAlY alloy. Met. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Met. Mater. Sci. 38 A, 2974–2983 (2007).

Caplan, D., Harvey, A. & Cohen, M. Oxidation of chromium at 890°–1200°C. Corros. Sci. 3, 161–IN8 (1963).

Dryepondt, S., Kirka, M. M. & List III, F. A. Oxidation Behavior of Ni-Based Alloys Fabricated by Additive Manufacturing. In CORROSION 2019, pp. 1–11, Paper No. C2019–13558 (2019).

Romedenne, M., Pillai, R., Kirka, M. & Dryepondt, S. High temperature air oxidation behavior of Hastelloy X processed by Electron Beam Melting (EBM) and Selective Laser Melting (SLM). Corros. Sci. 171, 108647 (2020).

Romedenne, M., Stack, P., Pillai, R. & Dryepondt, S. Isothermal and Cyclic Oxidation of Haynes 282 Processed by Electron Beam Melting (EBM) and Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) in Dry Air at 800 and >950 °C. JOM 74, 1–12 (2022).

Yamaura, S., Igarashi, Y., Tsurekawa, S. & Watanabe, T. Structure-dependent intergranular oxidation in Ni–Fe polycrystalline alloy. Acta Mater. 47, 1163–1174 (1999).

Trindade, V. B., Krupp, U., Wagenhuber, P. E., Virkar, Y. M. & Christ, H.-J. Studying the role of the alloy-grain-boundary character during oxidation of Ni-base alloys by means of the electron back-scattered diffraction technique. Mater. High. Temp. 22, 207–212 (2005).

Balogh, Z. & Schmitz, G. Diffusion in metals and alloys. Phys. Metall.: Fifth Ed. 1, 387–559 (2014).

Desgranges, C., Lequien, F., Aublant, E., Nastar, M. & Monceau, D. Depletion and voids formation in the substrate during high temperature oxidation of Ni-Cr alloys. Oxid. Met. 79, 93–105 (2013).

Rhines, F. N. & Wolf, J. S. The role of oxide microstructure and growth stresses in the high-temperature scaling of nickel. Met Trans. 1, 1701–1710 (1970).

Evans, H. E. Stress effects in high temperature oxidation of metals. Int. Mater. Rev. 40, 1–40 (1995).

Wei, F. I. & Stott, F. H. The development of Cr2O3 scales on iron-chromium alloys containing reactive elements. Corros. Sci. 29, 839–861 (1989).

Hou, P. Y. & Stringer, J. The effect of aluminum as an alloying addition or as an implant on the high-temperature oxidation of Ni-25Cr. Oxid. Met. 34, 299–321 (1990).

Yaedu, A. E. et al. Understanding preferential intergranular oxidation in alloy X-750 in 480 °C CO-CO2 environments at the nanoscale. Corros. Sci. 240, 112496 (2024).

Madhusudan, S. et al. High Temperature Intergranular Oxidation of Nickel Based Superalloy Inconel 718. High. Temp. Corros. Mater. 101, 873–884 (2024).

Weiser, M., Olszta, M. J., Engelhard, M. H., Zhu, Z. & Schreiber, D. K. Visualizing oxygen transport pathways during intergranular oxidation in Ni-Cr. npj Mater. Degrad. 7, 1–11 (2023).

Kruska, K., Olszta, M. J., Wang, J. & Schreiber, D. K. Intergranular corrosion of Ni-30Cr in high-temperature hydrogenated water after removing surface passivating film. npj Mater. Degrad. 8, 1–10 (2024).

Chyrkin, A., Cossu, C., Svensson, J.-E. & Froitzheim, J. Internal oxidation of a Fe–Cr binary alloy at 700–900 °C: the role of hydrogen and water vapor. Oxid. Met. 98, 273–289 (2022).

Pfeil, L. B. Improvement in heat-resisting alloys, UK Patent, No. 459848 (1937).

Hou, P. Y. The reactive element effect—past, present and future. Mater. Sci. Forum 696, 39–44 (2011).

Chevalier, S. What did we learn on the reactive element effect in chromia scale since Pfeil’s patent?. Mater. Corros. 65, 109–115 (2014).

Naumenko, D., Pint, B. A. & Quadakkers, W. J. Current Thoughts on reactive element effects in alumina-forming systems: in memory of John Stringer. Oxid. Met. 86, 1–43 (2016).

Ecer, G. M. & Meier, G. H. The effect of cerium on the oxidation of Ni-50Cr alloys. Oxid. Met. 13, 159–180 (1979).

Nagini, M. & Murty, B. S. Mechanical alloying: an advanced processing route for development of iron-based oxide-dispersion-strengthened alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 27, 2401111 (2025).

Falk-Windisch, H., Claquesin, J., Sattari, M., Svensson, J. E. & Froitzheim, J. Co- and Ce/Co-coated ferritic stainless steel as interconnect material for intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cells. J. Power Sources 343, 1–10 (2017).

Sattari, M., Sachitanand, R., Froitzheim, J., Svensson, J. E. & Jonsson, T. The effect of Ce on the high temperature oxidation properties of a Fe–22%Cr steel: microstructural investigation and EELS analysis. Mater. High. Temp. 32, 118–122 (2015).

Quadakkers, W. J., Holzbrecher, H., Briefs, K. G. & Beske, H. Differences in growth mechanisms of oxide scales formed on ODS and conventional wrought alloys. Oxid. Met. 32, 67–88 (1989).

Li, M., Qian, Y., Li, Y. & Zhou, Y. Beneficial effects of Ce implantation into preformed Cr2O3 scales on the subsequent oxidation of Ni-20Cr alloy. Oxid. Met. 61, 529–544 (2004).

Chyrkin, A., Froitzheim, J., Zurek, J. & Naumenko, D. Austenitization triggering breakaway oxidation of FeCr-base alloys at 900. C. Corros. Sci. 244, 112605 (2025).

Reddy, Chausson, M. J., Svensson, T. E. & Froitzheim, J. E. J. 11–23% Cr steels for solid oxide fuel cell interconnect applications at 800 °C—how the coating determines oxidation kinetics. Int J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 12893–12904 (2023).

Vayyala, A. et al. Effect of gas composition on the oxide scale growth mechanisms in a ferritic steel for solid oxide cell interconnects. Corros. Sci. 221, 111317 (2023).

Wilms, M. B., Rittinghaus, S. K., Goßling, M. & Gökce, B. Additive manufacturing of oxide-dispersion strengthened alloys: materials, synthesis and manufacturing. Prog. Mater. Sci. 133, 101049 (2023).

Quadakkers, W. J. Growth mechanisms of oxide scales on ODS alloys in the temperature range 1000–1100°C. Mater. Corros. 41, 659–668 (1990).

Wasilkowska, A., Bartsch, M., Messerschmidt, U., Herzog, R. & Czyrska-Filemonowicz, A. Creep mechanisms of ferritic oxide dispersion strengthened alloys. J. Mater. Process Technol. 133, 218–224 (2003).

Rakhmonov, J. U., Kenel, C., De Luca, A., Leinenbach, C. & Dunand, D. C. Effect of Y2O3 dispersoids on microstructure and creep properties of Hastelloy X processed by laser powder-bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 3, 100069 (2022).

Luu, D. N., Zhou, W. & Nai, S. M. L. Influence of nano-Y2O3 addition on the mechanical properties of selective laser melted Inconel 718. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 845, 143233 (2022).

Hoffman, A. K. et al. Oxidation resistance in 1200°C steam of a FeCrAl alloy fabricated by three metallurgical processes. JOM 74, 1690–1697 (2022).

Fedorova, I. et al. Oxidation behavior of additively manufactured Ti-added FeCrAl alloys. High. Temp. Corros. Mater. 101, 1155–1165 (2024).

Gunduz, K. O. et al. The effect of additive manufacturing on the initial High temperature oxidation properties of RE-containing FeCrAl alloys. Corros. Sci. 188, 109553 (2021).

Thompson, K. et al. In situ site-specific specimen preparation for atom probe tomography. Ultramicroscopy 107, 131–139 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This study was accomplished within the Swedish High Temperature Corrosion Centre (HTC) partly funded by the Swedish Energy Agency and its member companies (in this work Siemens Energy AB, AB Sandvik Materials Technology, Kanthal AB). The authors also gratefully acknowledge Chalmers Materials Analysis Laboratory (CMAL), where the materials characterizations were carried out. A.C. acknowledges his funding by the European Union, project MSCA4Ukraine, grant No. 1232975. The present publication reflects only the author’s views, and the European Union is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Chalmers University of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C. conceived and planned the experiments. A.C., A.F., M.S., E.W. carried out experiments and analyses. A.C. wrote the original draft. J.F., D.N., M.T., K.S. and M.H. reviewed and edited the manuscript. A.C. and J.F. received funding and supervised the work. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chyrkin, A., Fazi, A., Sattari, M. et al. PVD Ce-coating to mitigate intergranular oxidation of additively manufactured Ni-base alloy IN625. npj Mater Degrad 9, 117 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00677-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00677-5