Abstract

Many patients with COPD use inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) without proper indication. We developed a multifaceted tailor-made de-implementation strategy—including a toolbox, communication plan, and training—to reduce inappropriate ICS use in general practice. We evaluated its effectiveness (i.e. decline in percentage of patients with COPD that use ICS) and other outcomes during a 15-month study in Drenthe, the Netherlands. Less patients (−4.7%,95%CI: 2.6–6.7%) used ICS at the end of follow-up and the percentage of ICS-users declined by 8.2% (95%CI: 2.9–13.4%) across the 14 practices that fully participated in the project. ICS user percentages declined significantly moreover time in the fully participation group than in the control group (beta-regression, β = −0.041,SE = 0.011, p < 0.01). While these findings are promising, further research is needed to assess additional penetration and sustainability of the strategy in the region and to explore the applicability of comparable regional ICS de-implementation plans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous respiratory condition characterized by chronic respiratory symptoms like dyspnoea and cough. It is due to abnormalities of the airways and/or alveoli that cause persistent, often progressive, airflow obstruction1. Approximately 392 million people worldwide suffer from COPD2. Antimuscarinic and beta2-agonist drugs dilate the bronchi, relieve symptoms and improve lung function in COPD3. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are effective in suppressing the inflammatory response seen in asthma and are considered the cornerstone of asthma management4. Moreover, ICS can help reduce exacerbation risk in COPD patients, especially in those with a blood eosinophil count ≥ 300 cells/μL5,6,7. Therefore, the therapeutic value of ICS for COPD is limited to patients who have comorbid asthma and/or are prone to exacerbations where previous ICS treatment showed to reduce the patient’s exacerbation risk. According to a recent estimate, approximately 25% of COPD patients benefit from the use of ICS, while 60% of COPD patients in the Netherlands use ICS8.

Many patients use combination inhalers, often containing bronchodilators with ICS, without realizing it—leading to a lack of awareness of ICS use and positive perceptions driven by bronchodilator effects9. ICS use should be avoided in patients who do not benefit from its use for several reasons. First, several side-effects have been documented, like increased risk of osteoporosis, fractures, oral candidiasis, diabetes, cataracts, skin bruising, and pneumonia10,11,12. Second, inappropriate ICS use results in needless medication use and medical costs13. Therefore, inappropriate ICS use by patients with COPD should be de-implemented. De-implementation is the practice of abandoning ineffective and harmful medical practices to improve outcomes for patients and mitigate the unsustainable rise in healthcare care costs14. De-implementation is challenging and even more difficult than the implementation of effective new medical strategies15. To improve success rate it is important to give healthcare professionals the lead in reducing the low-value care that is targeted, to involve all stakeholders (especially patients) in the set-up and execution of the strategy, to take account of the regional context and cultural differences, and to design a tailormade strategy16,17. Most previous programs on ICS reduction in COPD have merely focused on de-prescribing ICS to patients who have no indication for ICS use18,19,20,21,22,23. The effectiveness of these programs in terms of reducing ICS use is limited, which is in contrast with the resounding results of the WISDOM study, a landmark double-blind randomized controlled trial on ICS withdrawal in patients with COPD24. In the WISDOM study, ICS withdrawal was considered successful, as it did not lead to an increased risk of exacerbations or greater need for changes in respiratory medication compared to patients who continued ICS therapy. The difference between the WISDOM results and real life studies may stem from participants’ awareness of ICS discontinuation, potentially prompting premature ICS restart due to temporary symptom changes18,25,26.

We aimed to reduce inappropriate ICS use by patients with COPD in a regional primary care setting with a multifaceted, tailor-made de-implementation strategy. The focus of this strategy was to (a) avoid first prescriptions of ICS to patients with no indication for ICS use, (b) withdraw inappropriate ICS use, and (c) prevent restarting ICS for inappropriate reasons. This paper describes the development and evaluation of the strategy, with a focus on its effectiveness, safety, implementation outcomes, and user satisfaction.

Methods

Study design

A mixed-method study was designed to evaluate the de-implementation strategy to De-implement inappropriate ICS use in COPD patients in the province of Drenthe (DECIDE), the Netherlands. The implementation strategy was evaluated using the Proctor framework27. The Proctor framework is a widely used model for evaluating implementation projects, distinguishing between implementation, service, and client outcomes. The study consisted of three interrelated parts: (1) a retrospective cohort analysis of regional ICS prescription data to assess changes in ICS use over time, serving as the primary outcome; (2) a prospective study in general practices evaluating the safety, effectiveness, and patient satisfaction of ICS withdrawal, while capturing strategy adoption and implementation fidelity; and (3) semi-structured interviews with patients and nurses to explore implementation outcomes and overall satisfaction. Box 1 provides an overview of evaluated outcomes. The study was exempted from ethics review by the medical ethics review board of the Radboud University Medical Center (file number 2021-12394) as it did not fall under the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act.

Regional context

Drenthe is one of the 12 provinces of the Netherlands, with approximately 500,000 inhabitants. All inhabitants of Drenthe receive care from one of the 140 general practices that are part of a regional general practices cooperation (RGPC) called ‘Doctor Drenthe’ (in Dutch: Dokter Drenthe, see www.dokterdrenthe.nl). In 2008, the RGPC launched a health insurer-funded integrated disease management (IDM) program for COPD, supported by dedicated RGPC nurse consultants that assist local general practices with implementation. In 2021, a large group of program-affiliated practices were invited to use the de-implementation strategy and participate in the evaluation study. Recruitment ran from July 2021 to September 2022, with several COVID-19-related delays.

Development of the de-implementation strategy to reduce inappropriate ICS use in COPD

We used the de-implementation guide of the Dutch program “To Do or not to Do” as framework to design our de-implementation strategy28. The step-by-step approach outlined in this de-implementation guide closely aligns with the Grol and Wensing model for implementing change in healthcare and incorporates a determinant framework to support comprehensive problem analysis29. We identified key regional stakeholders (i.e., a patient, chest physician, general practitioner (GP), clinical nurse specialist, practice nurse (PN), psychologist, pharmacist, and representative of the health insurance company) and invited them for one-on-one interviews about potential barriers and opportunities to reduce inappropriate ICS use in patients with COPD. Next, all stakeholders were invited for and participated in a digital stakeholder meeting to prioritize barriers and opportunities to reduce inappropriate ICS use in the region and decide on effective intervention strategies. The project team set up a de-implementation strategy based on the prioritized barriers and facilitators and consensus for the strategy was reached among the stakeholders.

De-implementation strategy

The de-implementation strategy comprised three main elements: a communication plan, training for general practice staff, and a digital toolbox. The communication plan aimed to inform and educate healthcare providers about the project and appropriate use of ICS in COPD management. A number of newsletters, personal outreach, and articles in professional magazines were published to enhance appropriate ICS prescribing practices and reduce inappropriate ICS use in patients with COPD. Additionally, project information was included in regional communication platforms and integrated into several asthma and COPD-related regional training courses to further raise awareness and promote best practices. Video material (in Dutch) was developed to support the implementation.

A training program was developed to help GPs and PNs reduce inappropriate ICS use in COPD, featuring a one-hour in-practice session by RGPC consultants, a digital self-learning version, and follow-up support through at least two consultant contacts.

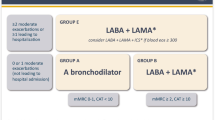

The toolbox (in Dutch, see eSupplement) was set-up with pre-existing and newly developed information, resources, and tools that general practice health care professionals could use to de-implement inappropriate ICS use in COPD. The toolbox covered key themes like diagnosing asthma and COPD, patient education on medication, appropriate ICS indications, selecting and supervising ICS withdrawal, and criteria for restarting ICS when needed. Examples of the tools that were available in the toolbox were: a decision tree on appropriate inhaler medication use for COPD, a flowchart to help select patients for ICS withdrawal, templates of patient information letters, a questionnaire to evaluate side effects of ICS, and links to informative videos on public websites. The RGPC’s consultants explained how to use the toolkit to GPs and PNs during the educational session.

Data collection and outcomes

Part 1. Regional data from integrated disease management for COPD

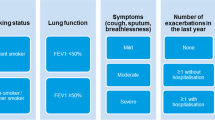

Every three months data was extracted from the electronic patient journal systems of all general practices that participate in the IDM program for COPD through a regional health information platform (VIPlive, Topicus, the Netherlands). The quarterly reports consisted of information on: the total number of patients with COPD registered with a general practice, the number that participated in the COPD IDM program, respiratory medication use (including ICS use), lifestyle (like smoking status), disease severity (like Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 s (FEV1) as a percentage of predicted value (FEV1%pred), exacerbations, and Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) scores. These data were aggregated at the practice level for patients who participated in the COPD IDM program and whose participation was claimed from a healthcare insurance company.

Outcomes for ICS use

The quarterly (Q) reports included information on the proportion of patients with current ICS use. Current ICS use is defined as having an ICS prescription issued within the past 28 days or a repeat prescription scheduled in the future, without a documented stop order for ICS within the past 28 days. Due to unforeseen and unavoidable COVID-19 measures at the time, the invitation of COPD patients to discuss ICS withdrawal with their PN was postponed until the first quarter of 2022 (Q1 2022). Current ICS use data collection commenced with the start of these visits, as this variable was included in the IDM dataset on 1 January 2022. Data collection concluded in the second quarter of 2023 (Q2 2023), following the final ICS withdrawal attempt in Q1 2023. Therefore, our analysis covers the period from Q1 2022 to Q2 2023.

Selection and categorization of general practices

Data from general practices was excluded from further analyses if (i) information of more than one quarterly reports was missing; (ii) the practice was new and still building a patient base (<1000 registered patients); or, (iii) the practice had just started with the COPD IDM program. Practices were categorized as (A) fully participated in the prospective evaluation study (part 2), (B) intended to reduce inappropriate ICS use in COPD patients in their practice but incomplete participation in the evaluation study, and (C) other general practices in Drenthe that participate in the COPD IDM program but did not receive or accept our invitation to participate in the study (i.e. ‘passive exposure’ group).

Part 2. Prospective study on ICS withdrawal in COPD patients in general practices

Data on ICS withdrawals in patients with COPD during the study period were collected from the participating general practices classified in Group A (full participation). A practice was considered to have fully participated if it met all of the following criteria: (i) agreement to take part in both the DECIDE program and the evaluation study; (ii) received training and follow-up support from a RGPC consultant ; and (iii) inclusion of patients who were willing to discontinue ICS and participate in the study. There was no control group or blinding in this study. One GP per practice gave written consent for practice participation in the study. Patients received study information and gave written informed consent before de-identified information on their ICS withdrawal attempt was forwarded to the project team.

Data collection

Participating practices kept a registration list of patients that stopped ICS use. This list included some characteristics of the patients (gender, age, smoking status), inhaler medication used before and after ICS withdrawal, occurrence of moderate to severe exacerbations in the 3 months after ICS withdrawal (defined as hospitalizations, antibiotics use, and/or prednisone use), and restarts (if any) of ICS including the reasons (e.g., newly diagnosed asthma). Patients that did not want to participate in the study but did agree to quit ICS were reported without further details on their characteristics or the success of their ICS withdrawal attempt. Participating patients were asked to fill out an online questionnaire after three months on their experience and satisfaction with ICS withdrawal.

Implementation outcomes and safety

Adoption of DECIDE was defined as the number and proportion of practices participating in the COPD IDM program with the intent to actively reduce inappropriate ICS use in their COPD patients. Fidelity was assessed across three key aspects:

-

ICS withdrawal – To ascertain the extent to which ICS was discontinued in COPD patients who do not benefit from it, assuming that 25% of the COPD population had a valid ICS indication8.

-

Respiratory medication management after withdrawal – This evaluated whether post-discontinuation prescriptions followed guideline recommendations, specifically whether a long-acting beta-2 agonist (LABA) and/or long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) was prescribed30. The Dutch guideline for general practitioners recommends to prescribe either a LABA or a LAMA, with no specific preference for LAMA.

-

Justification for restarting ICS – Was ICS reintroduced for a clinically appropriate reason (i.e., a new asthma diagnosis), or due to a moderate to severe exacerbation.

Safety was operationalized as the number of moderate and severe exacerbations after ICS withdrawal.

Part 3. Semi-structured interviews in patients and practice nurses

Interviews based on grounded theory methodology were used to explore patients’ and PNs’ experiences and attitudes towards the DECIDE strategy31. Patients with COPD and PNs that participated in the prospective study (Part 2) were approached for semi-structured interviews. All PNs who volunteered to be interviewed were practice nurses that supervised patients with COPD in their ICS quit attempts.

The interviews took place between September 2022 and May 2023 by two experienced interviewers (IM, LB). The interview guides were used flexibly and were modified to accommodate new topics identified by participants. An online communication platform (Zoom) was used to interview participants by video or audio only, depending on the interviewee’s preference. The interviews for patients lasted between 15 and 30 min, for PNs 20–45 min. The interviews were summarized by the interviewer and three randomly selected summaries of patient and PN interviews were checked for accuracy against the recordings by the second interviewer.

Analyses

Characteristics of the COPD patient population in Drenthe were described in numbers with percentages. General practice characteristics were described in medians with 25–75 percentiles (unless stated otherwise). For Part 1 change in the percentage of patients with ‘current ICS use’ (from Q1 2022 to Q2 2023: 6 time points of measurement) was estimated using a beta regression model that included time (i.e., Q1-2022 to Q2-2023), general practice category (i.e., category A, B, or C) and time * general practice category interaction terms with the passive exposure group (group C) as reference category. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, with p < 0.01 considered highly significant.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM) and betareg package in R (version 2025.05.0). Atlas.ti version 23 (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH) was used to code and analyse the patient and PN interviews. Open coding was used followed by axial coding and finally selective coding. Coding was done by two authors (LB, JG). After the coding of the first three interviews, the two evaluators compared and aligned their coding to ensure consistency.

Results

Recruitment and characteristics of population

Characteristics the COPD patient population

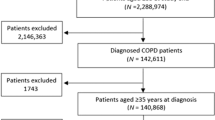

A total of 114 general practices in the province of Drenthe were active in the RGPC’s COPD IDM program in January 2022 (Fig. 1). An overall 2.2% of the general practice population was diagnosed with COPD and the majority of these patients (n = 6,129, 62.2%) were treated by a GP for their COPD. Of these patients 5,003 (81.6%) participated in the COPD IDM program with care data available for 4,269 (85.3%) of them. A total of 51.2% of these patients had used ICS in the previous year, while 37.6% were currently using ICS.

Recruitment of practices and patients for the prospective study (Part 2)

Of the practices interested in reducing inappropriate ICS use, 27 (75%) agreed to participate in the prospective study (Fig. 1). One practice dropped out, and seven reported no ICS withdrawals due to clinical and patient-reported reasons. In four practices, patients discontinued ICS, but declined study participation. In total, 15 practices reported ICS withdrawals (Fig. 1). COPD prevalence in these practices was 2.0%, with ICS prescribed to 49.8% of patients with COPD.

Overall, 67.1% of patients who had quit ICS participated in the study (n = 51; Fig. 3). Their median age was 70 years (IQR: 65–77), with 26 (51.0%) males. Median ICS use duration was 6 years (IQR: 3–11.25), and median time since COPD diagnosis was 10 years (IQR: 6–15). Most participants (n = 38, 74.5%) were former smokers. Forty-two patients (82.4%) completed the online questionnaire.

Selection of general practices for analysis of current ICS use (Part 1)

One group A practice and five group C practices were excluded from the analyses due to recent IDM program starts or missing reports. Therefore, prescription data were analysed for 14 fully participating (group A), 20 incompletely participating (group B), and 74 passive exposure (group C) practices. Practice and patient characteristics (Tables 1 and 2) showed no significant group differences.

Recruitment of patients and practice nurses for interviews (Part 3)

Nine patients (5 males) and six PNs (all women) were interviewed. eTables 2, 3 provide characteristics of these participants. The patients were between 52 and 84 years old and had used ICS for 3–14 years. All PNs had experience with successful ICS withdrawal in at least one of the patients with COPD.

Outcomes

Service outcomes (effectiveness and safety)

Change in current ICS use

Figure 2 illustrates the change in proportion of COPD patient with current ICS use over 15 months. Overall, current ICS use declined by 4.7% (95%CI: 2.6–6.7%). The smallest decrease in ICS use over time occurred in the passive exposure practices (Group C, 3.8%; 95%CI: 1.3–6.3%) though the decline was statistically significant (eTable 1, β = −0.028, SE = 0.008, p < 0.01). Incomplete participation practices (Group B) demonstrated a slightly larger reduction (5.2%;95%CI: 0.4–10.1%) but not significantly different from the passive exposure group (β = −0.008, SE = 0.011). Overall, the incomplete participation group had consistently more ICS users compared to the passive exposure group (β = 0.091, SE = 0.043, p < 0.05). fully participation practices showed the largest decrease in proportion of patients with current ICS use (8.2%, 95%CI: 2.9–13.4%). Full participation was associated with a significant greater reduction in the proportion of patients with current ICS use over time compared to group C (β = −0.041, SE = 0.011, p < 0.01).

ICS withdrawal attempts

An overall 76 patients stopped their ICS use in 15 practices (see Fig. 3) and 84.3% of reported withdrawal attempts were successful. Results varied widely between practices (see Table 3).

Safety

One patient was hospitalized for reasons unrelated to COPD. Five experienced moderate exacerbations (i.e., received a prescription for antibiotics and/or prednisolone) during follow-up, leading to ICS reintroduction in three patients as deemed necessary by the GP.

Implementation outcomes

Adoption

Of the 115 general practices in Drenthe involved in the COPD IDM programme, 82 responses were collected regarding their willingness to participate in the ICS de-implementation program. Although other practices did not receive a formal invitation, they may have learned about the initiative through local newsletters or informal channels. Among respondents, 36 (43.9%) expressed interest in reducing inappropriate ICS use. However, 9 practices did not participate in the prospective study due to prior piloting of the de-implementation strategy (n = 2), involvement in another ICS withdrawal project (n = 2), or believing participation was unnecessary as they were already taking sufficient measures to reduce inappropriate ICS use (n = 4). One practice gave no reason. Overall, the adoption rate among the practices was 43.9%, with 27 practices (32.9%) actually implementing the strategy.

Feasibility of the de-implementation strategy

ICS withdrawal in patients with COPD was considered feasible by the interviewed PNs. ‘Starting small’ with patients you know well and gradually expand was suggested as a successful strategy. Good collaboration between the GP and PN was considered a necessary precondition for successful ICS withdrawal. Moreover, PNs mentioned that the success of a withdrawal attempt depended on appropriate bronchodilator treatment. Advance notice of possible temporal symptom increase was considered critical to avoid inappropriate restart of ICS.

The DECIDE toolbox and training were found to be valuable, comprehensive and practical by the PNs. Frequently used toolbox components included: instruction on practice list creation of patients with COPD that use ICS; a flowchart for selecting COPD patients eligible for ICS withdrawal; an ICS side effect questionnaire; online patient information; and monitoring recommendations during withdrawal. PNs suggested enhancing the toolbox with visual/video materials on the pros and cons of ICS use and a brief user manual of the toolbox.

Fidelity of ICS withdrawal attempts

Among the 629 patients included in the 14 active practices with follow-up data, 233 patients (37.0%) had used ICS in the previous month. ICS treatment was withdrawn in 73 patients, leading to a reduction in current ICS use to 25.4%. However, due to the dynamic nature of the cohort, current ICS use at the end of follow-up was 28.9%.

Post-ICS withdrawal medication were available for 48 patients, five received no respiratory medication, 20 were prescribed a LABA, seven a LAMA, 13 a combination of LABA and LAMA, and 3 only short-acting bronchodilators. Thus, adherence to the Dutch guideline was 83.3%.

Fifty-one patients agreed to share data about the ICS withdrawal attempt with the research team, of which 43 (84.3%) did not restart ICS within 3 months (Fig. 3). In three cases ICS was reintroduced because of a moderate exacerbation. In five ICS was restarted because of a respiratory symptom increase. Three out of these eight ICS restarts were due to a moderate exacerbation that was considered a justified reason for reinitiation.

Patient satisfaction

A vast majority of 38 patients that filled out the digital questionnaire (90.5%) were positive on the supervision received during their ICS withdrawal attempt, categorizing it as good to excellent. Conversely, six patients (10.5%) would not recommend an ICS withdrawal to other patients. Four of those patients had experienced an exacerbation.

All nine patients that were interviewed were positive about their ICS withdrawal. They particularly valued the communication by and guidance from the PN. Patients also appreciated switching to more user-friendly inhalers. Patients and PNs emphasized that a strong relationship between them was key to ICS withdrawal decisions and success. Confidence in their ability to succeed and alignment of the ICS withdrawal attempt with their daily life were important success factors for patients. For example, one patient indicated that because she was retired she had more time and flexibility to stop ICS. A conversation with the GP helped hesitant patients. Key success factors included follow-up care, easy to access the PN, and reassurance that ICS could be restarted if needed.

Discussion

We aimed to reduce the inappropriate use of ICS in COPD through a regional, multifaceted de-implementation program for general practice. Over a 15-month period, current ICS use among patients with COPD in Drenthe decreased by 4.7%. This reduction may not appear substantial, but it is important to note that this decline was observed across the entire COPD population, including the 62.3% of patients that did not use ICS at the start of the project. In general practices that fully participated (Group A), end-of-project ICS use approached (i.e., 28.9%) the estimated 25% of patients who may benefit from its use. A vast majority (84.3%) of study participants did not restart ICS within 3 months. There were no severe exacerbations (i.e., hospitalizations) and only few moderate exacerbations requiring prednisolone or antibiotic treatment. Patients were satisfied with the supervision they received from the PNs. A positive relationship between patients and PNs seems essential to ensure successful ICS withdrawal. The availability of good follow-up care, easy access to the PN, and the ability to restart ICS if needed were all considered important success factors. One major limitation was the small number of practices that fully participated.

This project took place in the RGPC ‘Dokter Drenthe’ which performs slightly better on COPD care indicators than other RGPCs. Lower ICS use (51.2% regional vs 60.2% national), more frequent inhaler technique training, and more recorded smoking status may have influenced the results8,32. This may have facilitated implementation but also left less room for improvement.

Unlike previous studies that focused solely on ICS withdrawal, our strategy aimed to also prevent inappropriate initiation and minimize inappropriate reintroductions of ICS. This makes it difficult to compare results with previous studies. An exception is the study by Cole et al., which aimed to reduce inappropriate ICS use in UK general practices21. They trained GPs on appropriate ICS use, integrated alerts for inappropriate prescribing into electronic records, and offered incentives to reduce ICS in COPD patients. ICS use declined by 0.84% per quarter, which appears roughly comparable to the trend observed in our study. Our findings align with earlier studies on ICS withdrawal rates. For example, 27.3% of COPD patients withdrew ICS in a Dutch general practice study18. Another feasibility study found that 26.8% of patients were both eligible for and willing to discontinue ICS treatment22. In contrast, in our study only 16% of patients restarted ICS. Restart rates in previous studies ranged from 32.8–61.9%, especially in patients with severe disease or asthma COPD overlap, where asthma traits hinder withdrawal18,23,33. Notably, none of these studies found a link between ICS restart and exacerbations18,23,33. In our project, GPs were advised to consider restarting ICS after a single moderate exacerbation – an approach that may not always be clinically justified and could risk inappropriate use. However, paradoxically, offering this option appeared to support overall ICS de-implementation, as many patients viewed it as a key condition for agreeing to ICS withdrawal.

One strength of this study is the combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods to provide a broad insights in the effects of the de-implementation strategy. We used a well-known framework for evaluation of implementation, although some recommended outcomes are not reported in this paper27. Acceptability and appropriateness were assessed in a pilot phase, while penetration and sustainability will be explored in future stages. A cost evaluation was considered but not conducted due to the study’s pragmatic design34.

The real-life design enabled us to capture outcomes reflective of everyday clinical practice. For instance, information on ICS withdrawal attempts was not restricted to patients who consented to participate in the study, thereby enhancing the generalizability of our findings. This approach also introduced limitations. We only had access to aggregated data at a practice level, which meant that individual patient-level changes could not be assessed. For example, although we had access to the total number of patients that smoked within each practice, individual patient smoking status was not available. Consequently, we were unable to assess how smoking may have influenced individual treatment decisions—such as the ICS prescribing of, patients’ willingness to attempt ICS withdrawal, or the likelihood of successfully doing so.

Additionally, the number of patients with COPD included in the reports fluctuated over time—although the overall numbers remained relatively stable (i.e., increased from 4,156 to 4,385 over the study period). Another study limitation is the absence of a control region. Substantial differences between regional COPD IDM programs and patient populations made a comparison impossible.

A key strength of our de-implementation plan was its broad focus—not only on withdrawing inappropriate ICS in COPD patients, but also on reducing initial overprescribing and unnecessary restarts. Even non-active practices were likely influenced through education, media, and local clinical leaders. The strategy was tailored to regional goals and was strongly supported by local stakeholders.

We found a critical gap between a promising level of initial engagement and the relative small number of practices that became active participants in the project. Group B encompassed a heterogeneous mix of practices —from those casually interested in reducing ICS use to highly motivated ones with patients that were willing to withdrawn ICS but no study participation. This heterogeneity complicates interpretation. Given the small group and high variability, further subdivision of practices was not feasible. Nonetheless, this finding underscores the need for extra targeted support mechanisms to convert early enthusiasm into sustained actions. However, we anticipated a ripple effect in participation, fuelled by the success stories reported by the actively involved general practices. Key issues for further research include the long-term effectiveness of the de-implementation strategy, identify barriers to active participation among practices that initially expressed interest, options to upscale the strategy to RGPCs in other regions, and the role of eosinophil testing in guiding ICS treatment in patients with COPD35,36. The latter was not added as a strategy at the time of our project, as it is not recommended in the current Dutch general practitioners guideline for COPD30.

Conclusion

This study evaluated a regional de-implementation strategy aimed at reducing inappropriate ICS use in patients with COPD. The strategy led to a relevant reduction in ICS prescriptions across the region, with both patients and practice nurses expressing high levels of satisfaction and engagement. While these findings are promising, further research is needed to assess further penetration of the strategy in the region and its long-term sustainability, and to explore the applicability of comparable plans in other regions.

Data availability

The data will be made available through the Radboud Data Repository and are expected to be accessible from October 2025.

References

Celli, B. et al. Definition and nomenclature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: time for its revision. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 206, 1317–1325 (2022).

Adeloye, D. et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 10, 447–458, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00511-7 (2022).

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). https://goldcopd.org/2025-gold-report/ (2025).

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). https://ginasthma.org/2025-gina-strategy-report/ (2025).

Pascoe, S., Locantore, N., Dransfield, M. T., Barnes, N. C. & Pavord, I. D. Blood eosinophil counts, exacerbations, and response to the addition of inhaled fluticasone furoate to vilanterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a secondary analysis of data from two parallel randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 3, 435–442 (2015).

Bafadhel, M. et al. Predictors of exacerbation risk and response to budesonide in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a post-hoc analysis of three randomised trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 6, 117–126 (2018).

Siddiqui, S. H. et al. Blood eosinophils: a biomarker of response to extrafine beclomethasone/formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 192, 523–525 (2015).

Fens, T., van der Pol, S., Kocks, J. W. H., Postma, M. J. & van Boven, J. F. M. Economic impact of reducing inappropriate inhaled corticosteroids use in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: ISPOR’s guidance on budget impact in practice. Value Health 22, 1092–1101 (2019).

Gilworth, G., Harries, T., Corrigan, C., Thomas, M. & White, P. Perceptions of COPD patients of the proposed withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids prescribed outside guidelines: a qualitative study. Chron. Respir. Dis. 16, 1479973119855880 (2019).

Yang, I. A., Ferry, O. R., Clarke, M. S., Sim, E. H. A. & Fong, K. M. Inhaled corticosteroids versus placebo for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3, CD002991 (2023).

Price, D. B. et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and onset of type 2 diabetes and osteoporosis: matched cohort study. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 29, 38 (2019).

Pace, W. D., Callen, E., Gaona-Villarreal, G., Shaikh, A. & Yawn, B. P. Adverse outcomes associated with inhaled corticosteroid use in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann. Fam. Med. 23, 127–135 (2025).

Verkerk, E. W., Tanke, M. A. C., Kool, R. B., van Dulmen, S. A. & Westert, G. P. Limit, lean or listen? A typology of low-value care that gives direction in de-implementation. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 30, 736–739 (2018).

Prasad, V. & Ioannidis, J. P. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implement. Sci. 9, 1 (2014).

Born, K., Kool, T. & Levinson, W. Reducing overuse in healthcare: advancing Choosing Wisely. BMJ 367, l6317 (2019).

Colla, C. H., Mainor, A. J., Hargreaves, C., Sequist, T. & Morden, N. Interventions aimed at reducing use of low-value health services: a systematic review. Med. Care Res. Rev. 74, 507–550 (2017).

Verkerk, E. W. et al. Reducing low-value care: what can we learn from eight de-implementation studies in the Netherlands?. BMJ Open. Qual. 11, e001710 (2022).

van den Bemt, L. et al. Pragmatic trial on inhaled corticosteroid withdrawal in patients with COPD in general practice. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 30, 43, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-020-00198-5 (2020).

van Schayck, O., Chavannes, N. & Kocks, J. W. Terugdringen van onjuist ICS-gebruik bij COPD. Huisarts-. en. Wet. 63, 30–33, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12445-020-0929-6 (2020).

Patel, I. The future hospital: integrated working and respiratory virtual clinics as a means of delivering high-value care for a population. Future Hosp. J. 3, s28 (2016).

Cole, J. N., Mathur, R. A. & Hull, S. A. Reducing the use of inhaled corticosteroids in mild-moderate COPD: an observational study in east London. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 30, 34 (2020).

Harries, T. H. et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids from patients with COPD with mild or moderate airflow limitation in primary care: a feasibility randomised trial. BMJ Open. Respir. Res. 9, e001311 (2022).

Nielsen, A. O. et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with COPD - a prospective observational study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 16, 807–815 (2021).

Magnussen, H. et al. Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1285–1294 (2014).

Kruis, A. L. et al. Primary care COPD patients compared with large pharmaceutically-sponsored COPD studies: an UNLOCK validation study. PLoS One 9, e90145 (2014).

Whittaker, H. R., Wing, K., Douglas, I., Kiddle, S. J. & Quint, J. K. Inhaled corticosteroid withdrawal and change in lung function in primary care patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in England. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 19, 1834–1841 (2022).

Proctor, E. et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 38, 65–76 (2011).

van Dulmen, S., Kool, T. & Verkerk, E. Deimplementatiegids voor het terugdringen van niet-gepaste zorg in uw organisatie. IQ HealthCare, (Radboudumc, Nijmegen, 2019).

Wensing, M., Grol, R. & Grimshaw, J. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in clinical practice. Third edition edn, (Wiley Blackwell, 2020).

Bischoff, E., Bouma, M., Broekhuizen, L., Donkers, J., Hallensleben, C., de Jong, J., Snoeck-Stroband, J., In ’t Veen, J.C. van Vugt, S. Wagenaar, M. NHG Guideline COPD (M26). Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG); April 2021. https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/copd (2025).

Charmaz, K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd edition, (Sage, 2014).

InEen. Transparante ketenzorg 2021. Rapportage zorggroepen diabetes mellitus, vrm, copd en astma. Spiegel voor het verbeteren van chronische zorg. (InEen, 2022).

Magnussen, H. et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids versus continuation of triple therapy in patients with COPD in real life: observational comparative effectiveness study. Respir. Res. 22, 25 (2021).

Gold, H. T., McDermott, C., Hoomans, T. & Wagner, T. H. Cost data in implementation science: categories and approaches to costing. Implement. Sci. 17, 11 (2022).

Lee, J. H., Kim, S. & Oh, Y. M. A prediction scoring model for the effect of withdrawal or addition of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 18, 113–127 (2023).

Chalmers, J. D. et al. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: a European Respiratory Society guideline. Eur. Respir. J. 55, 2000351 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all stakeholders involved in developing the implementation strategy. We are also grateful to the general practitioners, practice nurses, and patients who participated in the project. In particular, we would like to thank the practice consultants from Dokter Drenthe for their invaluable dedication and support throughout the project. Finally we would like to thank Irma Maassen for her help with the interviews and Reinier Akkermans for his help with the Beta-regression.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Healthcare Institute of the Netherlands (in Dutch: Zorginstituut Nederland). The preliminary results of this study have been presented at the CAHAG conference 2023, Zeist The Netherlands (in Dutch).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.B., A.P., and J.B. are local experts. L.B., B.B., T.S. and T.K. designed the study. The de-implementation strategy was developed with regional experts, including B.B., J.B. and A.P. B.B., J.B., A.P. were responsible for recruitment. J.G., J.B. and A.P. were responsible for data collection with support from L.B. L.B., T.S., and J.G. analysed the data and L.B. drafted the manuscript with initial support from T.S., T.K. and E.B. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript, contributing important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van den Bemt, L., van Bremen, B., de Boer, J. et al. De-implementation of inappropriate inhaled corticosteroid use in patients with COPD in general practice, results of a mixed methods study. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 35, 44 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00448-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00448-4