Abstract

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are common in people at clinical high-risk for psychosis (CHR), however, the relationship between ACEs and long-term clinical outcomes is still unclear. This study examined associations between ACEs and clinical outcomes in CHR individuals. 344 CHR individuals and 67 healthy controls (HC) were assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), the Bullying Questionnaire and the Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA). CHR were followed up for up to 5 years. Remission from the CHR state, transition to psychosis (both defined with the Comprehensive Assessment of an At Risk Mental State), and level of functioning (assessed with the Global Assessment of Functioning) were assessed. Stepwise and multilevel logistic regression models were used to investigate the relationship between ACEs and outcomes. ACEs were significantly more prevalent in CHR individuals than in HC. Within the CHR cohort, physical abuse was associated with a reduced likelihood of remission (OR = 3.64, p = 0.025). Separation from a parent was linked to an increased likelihood of both remission (OR = 0.32, p = 0.011) and higher level of functioning (OR = 1.77, p = 0.040). Death of a parent (OR = 1.87, p = 0.037) was associated with an increased risk of transitioning to psychosis. Physical abuse and death of a parent are related to adverse long-term outcomes in CHR. The counter-intuitive association between separation from a parent and outcomes may reflect the removal of a child from an adverse environment. Future studies should investigate whether interventions targeting the effect of specific ACEs might help to improve outcomes in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Some of the most studied environmental and psychological risk factors for psychosis are Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)1. ACEs include different traumatic experiences such as psychological and physical abuse and neglect, sexual abuse, parental loss or separation, and bullying. Several studies have consistently pointed to a heightened risk of psychosis associated with ACEs2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, and that ACEs are related to negative outcomes in schizophrenia spectrum disorders, such as poor functioning and persistence of symptoms11. Mall and colleagues12 reported that individuals who experienced ACEs showed 2.44 times increased odds of developing schizophrenia compared to those who did not. These compelling findings not only suggest a plausible causal connection between ACEs and the onset of schizophrenia spectrum disorders but also highlight the critical need for in-depth exploration of the links between specific ACEs and their cumulative effects on psychosis outcomes.

Most previous studies on the role of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) on psychopathological long-term outcomes in psychotic disorders have relied on samples of patients with established psychosis. The extent to which these measurements are confounded by effects of illness duration and treatment, or by recall bias, is therefore unclear13. One way to reduce the potential effects of these confounders is to evaluate ACEs before the onset of illness, in people at clinical high-risk for psychosis (CHR).

ACEs are more common in CHR individuals than in healthy volunteers14,15, with a meta-analytical mean prevalence rate of 86.8%16. Furthermore, around 5% of this population also meets criteria for a comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)17. This is particularly relevant considering the increasing evidence suggesting that trauma exposure is associated to both transition to psychosis18,19 and higher severity of attenuated psychotic symptoms20. However, people at CHR may experience other adverse clinical outcomes, such as non-remission of symptoms and poor functioning at the 24-months follow-up8,21,22. Moreover, a larger proportion of the CHR population experience these outcomes than the minority that develop a psychotic disorder21,22,23. Childhood trauma has been consistently associated with worse functioning at an adult age, including poorer cognitive performance24, worse social functioning25 and health outcomes26, for both general and clinical populations. However, factors linked to non-remission or poor functioning have been much less studied than factors associated with increased risk of transitioning to psychosis.

In particular, social functioning and subjective quality of life are recognized as important treatment outcomes in psychosis and psychosis risk27,28,29. They have been described as global constructs or as individual’s ability to adapt to societal, familial, and professional demands. ACEs in individuals with psychosis have been associated with disruptions to social and academic functioning in adult life30, however, little is known about the contribution of ACEs to impaired social functioning in people at CHR of psychosis. Understanding the factors that contribute to and are associated with the emergence of negative medium- and long-term outcomes is critical for eventually developing interventions to prevent ACEs and developing psychological treatments designed to reduce the detrimental effects of ACEs.

The aims of the present study were to assess whether specific ACESs are related to adverse outcomes (non-remission of CHR symptoms, levels of social and occupational functioning, and transition to psychosis) in people at CHR. We tested the hypothesis that ACEs would be associated with non-remission of symptoms, low level of social and occupational functioning as well as with transition to psychosis.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a multicentre, prospective study. ACEs and clinical characteristics were collected from participants in the The EUropean Network of National Schizophrenia Networks Studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) High Risk study31, a naturalistic prospective case-control study involving 11 sites in 6 countries (London, Amsterdam, The Hague, Basel, Cologne, Copenhagen, Paris, Barcelona, Vienna, Sao Paulo, and Melbourne). The sites were chosen to represent a blend of rural and urban regions, featuring diverse proportions of minority ethnic groups, and assessment measures were standardized across the different countries32. The total EU-GEI sample comprised 344 CHR individuals and 67 healthy controls (HC). For individuals at CHR, exclusion criteria were past or present diagnosis of psychotic disorders or neurological disorders and estimated intelligence quotient (IQ) lower than 60. For HC, inclusion criteria were not meeting criteria for the CHR state, no past or present diagnosis of psychotic disorders or neurological disorders and being recruited from the same geographical areas as the CHR group. Ethical approval was obtained from each site’s local research ethics committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

Clinical assessment and outcomes

At baseline, the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS)33 was used to determine whether participants met inclusion criteria for the CHR state. Participants meeting CHR criteria who were receiving antipsychotic medication were included, provided the medication had not been prescribed for a psychotic episode. Participants were also evaluated with the GAF disability scale34. Raters were trained in the use of the CAARMS and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) prior to the study and completed online training videos every 12 months from study onset to assess interrater reliability (see previous publication35). Data on age, sex, and race were obtained using the Medical Research Council Sociodemographic Schedule36. IQ was estimated using the shortened version of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale37. Current and lifetime mental disorders were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I and II Disorders (SCID-I, SCID-II)38,39.

Participants were monitored for up to 5 years, with face-to-face interviews at 6, 12 and 24 months. Transition to psychosis was defined according to the CAARMS criteria33. Where possible, participants were assessed with the SCID-I at each planned follow-up to establish a formal diagnosis according to DSM-IV criteria40. This allowed to ascertain diagnosis of psychotic disorder or other psychiatric disorders throughout the duration of the study. If a participant was unable to attend a follow-up or was lost at follow-up, Electronical Health Care Records (eHCR) were used to determine if transition to psychosis had occurred. This information was identified in eHCR as a code (i.e. International Classification of Diseases code) or as a single entry (i.e. name of diagnosis). Remission from the CHR state was defined as an individual no longer meeting CAARMS inclusion criteria at the last available follow-up41. Level of functioning was defined using the GAF disability scale based on the last available follow-up data. GAF data were subsequently dichotomized into high and low GAF, with high GAF score equal or greater than 60 entailing better functioning in CHR samples42,43. This approach is in line with previous studies and reflect the clinical significance of the GAF scores (GAF \(\ge\) 60 corresponds to relatively good functioning), 44.

Adverse Childhood experiences (ACEs)

ACEs were assessed retrospectively using the Brief version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)45, the Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA-Q)46 and the Retrospective Bullying Questionnaire47.

The CTQ is a 25-item self-report questionnaire which assesses traumatic experiences before the age of 17. Individuals rated their level of exposure on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). This generated a total score, as well as subscores for five domains: emotional abuse (EA), physical abuse (PA), sexual abuse (SA), emotional neglect (EN) and physical neglect (PN). Cut-off scores were then used to classify individuals into groups based on the presence or absence of clinically significant histories of abuse and neglect. These moderate to severe thresholds have been previously used identify these cases while minimizing the risk of false positives48,49. Moderate-severe cut-off scores for each subscale were \(\ge\) 13 for EA; \(\ge\) 10 for PA; \(\ge\) 8 for SA; \(\ge\) 15 for EN; and >= 10 for PN50. Being identified as positive for a category corresponds with endorsing a substantive number of experiences as “often true”.

The CECA-Q assesses traumatic experiences such as the death of a parent, separation from parents (including being in foster care), parental discordance, lack of adult support, poverty, cruelty, and violence. These different measures of ACEs were categorized as present or absent.

The Retrospective Bullying Questionnaire measures the severity of the bullying experience (emotional, psychological, or physical violence) on a 0 to 3 score. Then, exposure to childhood bullying was dichotomized using \(\ge\) as the cut-off point (0 = “absent” and \(\ge\) 1 = present).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 17 (StataCorp, 2023). Demographic and clinical data were compared using independent t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Significant effects are reported at p < 0.05. To assess collinearity among the ACEs variables, we used the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Only ACEs items that did not show multicollinearity, as indicated by VIF values below 10, were included in the analyses.

An a priori sample size calculation was conducted based on a 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error, and 80% statistical power. Each outcome was dichotomous, and the approximate prevalence of each outcome was estimated from previously reported data in the literature. For the transition to psychosis in CHR populations, a prevalence of 19.0% was used51. For symptom remission in CHR, a prevalence of 33.4% was applied52. Lastly, a prevalence of 25.0% was chosen for poor functional prognosis53. This yielded required sample sizes of 237, 342, and 289 for each outcome, respectively.

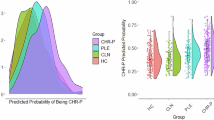

We used the whole CHR sample to analyze the relationship between ACEs and transition to psychosis. Analyses of other outcomes were limited to participants for whom data on symptom remission and functioning were available. Specifically, the sample used to analyze the association between symptom remission and ACEs included 241 CHR individuals, 74.27% of whom completed a face-to-face assessment at 12 months, and 34.63% of those completed an additional assessment at 24 months. At the last follow-up, 70 showed symptom remission, and 171 still met CHR criteria. Healthy controls (HC) were not included in the transition and remission analyses. The sample available to analyze the association between functioning (measured using the Global Assessment of Functioning, GAF disability) and ACEs comprised 221 CHR individuals and 50 HC. Among the CHR, 68.33% were assessed face-to-face at 12 months, and 39.73% of those completed an additional assessment at 24 months. 122 CHR participants presented poor functioning and 99 good functioning while all HC presented good functioning. Participants without information on symptom remission or functioning were excluded from these analyses. In each analysis, sex, age, race and site were included as covariates. Approximate IQ was also included as a covariate, as evidence suggests that neurocognitive function is one of the primary determinants of functional outcome in CHR individuals54.

All outcomes were analysed using stepwise regression and multilevel logistic regression models with data clustered by site as a random intercept, to consider that observations from the same site could be correlated. In the first step we conducted a stepwise regression, including all the variables related to ACEs measures and socio-demographic variables that could potentially influence the outcomes (Table 1), which is a method of fitting regression models in which the choice of predictive variables is carried out by an automatic procedure. We used a significance level of 0.255 for variables to enter and stay in the model. In the second step we performed a multilevel logistic regression (melogit) to analyze the binary outcomes based on a subset of variables from the stepwise regression and accounting for clustering by site. This approach allows for the examination of how specific factors are associated with the outcomes, controlling for the non-independence of observations within sites, and adjusting for potential confounding variables identified in the stepwise regression. Variables with a final significance p < 0.05 were considered significant in the model.

Results

Demographic and clinical data

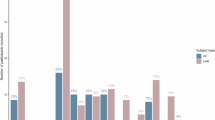

Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample are detailed in Table 1. HC had more years in education, higher IQ, and higher GAF scores than CHR individuals. Most ACEs were significantly more frequent in the CHR group, except for death of a parent, separation from a parent, and being taken into care. 65 individuals transitioned to psychosis during the follow-up (CHR-T) and 279 did not (CHR-NT). The mean time to transition to psychosis was 373.14 days (SD = 404.10). Black race was associated with increased odds of transition to psychosis (OR = 1.77, 95% CI [1.10, 2.83], p = 0.017) and lower odds of good functioning at follow-up (OR = 0.43, 95% CI [0.23, 0.81], p = 0.009) compared with White race.

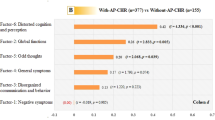

Relationship between ACEs and symptom remission

Physical abuse was associated with a more than a threefold increase in odds of CHR symptoms non-remission (OR = 3.64, 95%CI 1.18 to 11.23, p = 0.025). Conversely, separation from a parent substantially increased the odds of remission (OR = 0.32, 95%CI 0.14 to 0.73, p = 0.011). The results are detailed in Table 2 and Fig. 1.

Relationship between ACEs and functioning

Individuals who experienced separation from a parent had 1.77 times the odds of presenting with good functioning as measured with the GAF disability scale compared to individuals who had not experienced parental separation (OR = 1.77, 95% CI 1.01–3.07, p = 0.040). HC were finally excluded from the model because their status perfectly predicted the functioning, as all the controls presented high functioning, resulting in no variation for the model to estimate an effect (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Relationship between ACEs and transition to psychosis

Individuals reporting the death of a parent presented increased odds of transition to psychosis (OR = 1.87, 95% CI 1.04–3.38, p = 0.037), (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between ACEs and long-term outcomes in a large multi-centre cohort of individuals at CHR for psychosis, including participants with diverse backgrounds and ethnicities from Europe and South America. As expected, based on previous studies56,57,58, the CHR group reported significantly higher levels of several different forms of ACEs (CTQ total score, all five trauma subtypes, CECA trauma subtypes, and bullying). Our hypotheses, that within the CHR group, ACEs would be associated with adverse clinical outcomes, were partially confirmed.

Physical abuse was associated with a reduced likelihood of remission from the CHR state. Several studies have related the experience of ACEs to higher chances of suffering a mental health condition in adulthood59,60,61. Physical abuse, particularly in the formative years, can have profound and long-lasting effects on psychological well-being and development. This type of trauma can disrupt the psychological development and the ability to regulate emotions and distress62. Research has shown that individuals who have experienced physical abuse may have a greater vulnerability to a range of mental health disorders63. The trauma stemming from the abuse may lead to changes in emotion regulation, stress response, and impulse control64. For example, it can alter the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to a heightened stress response that could exacerbate symptoms of mental health disorders65. Physical abuse can also erode trust in others66,67, potentially preventing or delaying help-seeking when distress arises and making the formation of therapeutic relationships — a crucial aspect of many mental health treatments — more challenging.

Contrary to our hypothesis, childhood separation from a parent was associated with increased probability of CHR symptom remission and with a higher level of functioning and was not associated with transition to psychosis. Importantly, while these associations are significant, these participants still met intake criteria for CHR status. Both groups - those with and without parental separation – demonstrate individual vulnerability to developing a mental health disorder. This vulnerability might also be influenced by other risks factors, including genetic predisposition, exposure to other ACEs or a combination of these factors. Nonetheless, these counter-intuitive findings might be explained by the child’s removal from a challenging or difficult family environment68,69. Past studies have reported greater odds of psychosis and other mental health conditions following parental separation70,71,72. However, children who have navigated the challenges of parental separation often develop a greater degree of resilience72,73. The process of adapting to significant life changes can foster coping skills and psychological strength, which might aid in recovery from mental health conditions. Childhood separation from their parents due to difficulties within the family could often mean being placed in more supportive environments, whether with other family members, in foster care, or through adoption, along with increased access to mental health resources. These environments and therapeutic services can provide the emotional support and stability needed for the child to thrive and for mental health symptoms to remit74. Parental separation changes the family dynamics and might relieve the child from certain dysfunctional roles they might have adopted, i.e. acting as a caretaker or mediator, roles that can be associated with distress and anxiety75. For some, the experience of separation and the subsequent challenges can lead to significant personal growth and development, while for others, separation from a parent can mainly be a source of trauma and emotional distress72.

CHR individuals who had experienced the death of a parent before age 11 had more than two-fold increase likelihood of later transition to psychosis. Consistent with this finding, a recent large multi-centre study that investigated the relationship between early parental death in childhood and psychosis reported significantly greater odds of psychosis with parental loss and even greater odds with the loss of both parents76. The experience of losing a parent before reaching adulthood is among the most traumatic events one can endure, with a significant increase in the risk of adjustment, psychotic, and personality disorders, among others77,78. The environment and conditions a child faces after the loss of a parent may have a greater long-term impact on their mental health than the event of death itself76, and these post-loss conditions can either mitigate or intensify the potential negative outcomes. On the other hand, a recent meta-analysis reported no association between CTQ subtypes and transition to psychosis79, with the exception of sexual abuse, which was correlated with a higher likelihood of transition. Furthermore, this meta-analysis reported high heterogeneity among the included studies and follow-up periods ranging from 6 months to 15 years, which limits the interpretation of the results. An earlier investigation of individuals drawn from the same cohort reported that emotional abuse was associated with transition to psychosis80. However, in the latter study, follow-up of the CHR sample had not been fully completed, with a duration of only 24 months, and only 11.9% had developed psychosis at the time of analysis. In the present study, the follow-up period was up to 5 years, and 11 participants that had previously been classed as non-transitioned had gone on to develop psychosis, increasing the transition rate to 17%. These differences are likely to account for the non-replication of this preliminary finding.

Finally, even though it was not the primary focus of our study, it is important to highlight the significant association found between Black race and poorer outcomes at follow-up, including lower functioning and higher odds of transitioning to psychosis. This finding aligns with previous literature indicating that ethnic minority and migrant groups are at greater risk of mental health difficulties, particularly psychosis, with Black individuals being at the highest risk81. Several explanations have been proposed, including the impact of racial harassment and discrimination experienced by minority groups82, the disproportionate risk of deprivation83, and, in some cases, the migration processes, which can be a traumatic experience itself84.

ACEs have been consistently associated with poor mental health, including and not limited to the development of psychosis. ACEs are also significantly more prevalent in CHR than in HC. ACEs seem to therefore be good candidate targets for preventive interventions85,86. Specifically, it is essential to understand the role of protective factors against ACEs in individuals at CHR. Previous studies highlight the protective potential of community engagement and mother-child relationships in mitigating negative outcomes, even after an adverse event has occurred78. However, it remains unclear whether these factors could also serve as protective mechanisms in preventing the development of psychotic symptoms.

Furthermore, therapeutic interventions may need to be tailored to address the specific needs of individuals who have experienced ACEs, and treatment plans may need to be more intensive and longer in duration. Given the high prevalence of ACEs in individuals at CHR; interventions targeting this population should always aim to be trauma-informed. Additionally, for those with comorbid PTSD, trauma-focused interventions should be offered. These include Eye Movement Desensitisation Reprocessing, which is being implemented within some early intervention for psychosis services with some positive results87,88,89, as well as prolonged exposure treatments, which have demonstrated equal or superior efficacy in populations within the psychosis spectrum90,91. Interventions based on cognitive processing within the framework of cognitive-behavioural therapy have also demonstrated a robust effect on trauma-related symptoms and cognitions in psychotic disorders92,93.

Finally, early preventive interventions, including school-based interventions able to reach most children and adolescents regardless of their ethnic and financial background, intensive support and interventions within the family of origin, temporary or prolong foster care in those cases where it is not possible to successfully support the original family, might be appropriate72,94,95,96.

Limitations

Although information on ACEs was collected using well-established instruments (CTQ, CECA, and the Retrospective Bullying Questionnaire) in adolescents and young adults who had not yet developed psychosis, the assessments were still retrospective and can therefore be affected by factors such as recollection, repression or reporting biases13,97. Nevertheless, previous findings support the predictive validity of retrospective measures of ACEs on clinical outcomes98 and indicate that retrospective assessments are more likely to underestimate rather than overestimate the prevalence of ACEs97. Another potential limitation is the use of the GAF to assess functioning, as it blends clinical symptoms, social functioning, and academic/role functioning into a single score. This approach may obscure nuanced differences in functional profiles, particularly in CHR populations, where functional decline is less pronounced than in progressed psychosis and profiles are often imbalanced (e.g., intact social functioning alongside declining academic performance). Missing data at follow up, especially in relation to the variables of symptom remission and functioning, as well as the low number of events in some of the included ACEs might have reduced the sample’s statistical power. A larger sample would therefore be appropriate, in particular, to replicate our findings that childhood separation from a parent is associated with increased probability of CHR symptom remission, and with a higher level of functioning. The statistical analysis employs a stepwise regression model, which can introduce biases in variable selection and increase the risk of overfitting. To minimize this risk, covariates for the analyses were chosen based on factors that have shown a strong association with the outcomes in prior literature. Nevertheless, it remains essential to replicate these findings in independent samples to confirm their robustness. Finally, ACEs, their timing, their influence and relationship with one another, are incredibly complex and have an impact on biological, psychological and social pathways99,100. A much larger multi-modal dataset with detailed premorbid and longitudinal data would allow the in-depth analysis of the effects of ACEs on the bio-psycho-social systems.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that some ACEs in the CHR population are associated with adverse clinical outcomes. Although the relationship between ACEs and psychosis is complex, addressing ACEs within early intervention services, for example offering trauma-focused interventions, could be beneficial. Additionally, preventive strategies targeting early childhood and adolescence within the school environment might have the potential to mitigate or modify the effects of ACEs on long-term outcomes. Further research is needed to confirm this association and to refine intervention approaches.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to restrictions from the ethical approvals obtained, which do not include provisions for data sharing. Therefore, the data cannot be shared.

References

Zhang, L. et al. Adverse childhood experiences in patients with schizophrenia: related factors and clinical implications. Front. Psychiatry 14, 1247063 (2023).

Janssen, I. et al. Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 109, 38–45 (2004).

Lardinois, M., Lataster, T., Mengelers, R., Van Os, J. & Myin-Germeys, I. Childhood trauma and increased stress sensitivity in psychosis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 123, 28–35 (2011).

van Nierop, M. et al. Psychopathological mechanisms linking childhood traumatic experiences to risk of psychotic symptoms: analysis of a large, representative population-based sample. Schizophr. Bull. 40, S123–S130 (2014).

Varese, F. et al. A meta-analysis of patient- control prospective- andcross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr. Bull. 38, 661–671 (2012).

Isvoranu, A. M. et al. A Network Approach to Psychosis: Pathways Between Childhood Trauma and Psychotic Symptoms. Schizophr. Bull. 43, 187–196 (2017).

Tognin, S. et al. Emotion Recognition and Adverse Childhood Experiences in Individuals at Clinical High Risk of Psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 46, 823–833 (2020).

Popovic, D. et al. Traces of Trauma: A Multivariate Pattern Analysis of Childhood Trauma, Brain Structure, and Clinical Phenotypes. Biol. Psychiatry 88, 829–842 (2020).

Stanton, K. J., Denietolis, B., Goodwin, B. J. & Dvir, Y. Childhood Trauma and Psychosis: An Updated Review. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 29, 115–129 (2020).

Inyang, B. et al. The Role of Childhood Trauma in Psychosis and Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. Cureus 14, e21466 (2022).

Thomas, S., Hofler, M., Schafer, I. & Trautmann, S. Childhood maltreatment and treatment outcome in psychotic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 140, 295–312 (2019).

Mall, S. et al. The relationship between childhood trauma and schizophrenia in the Genomics of Schizophrenia in the Xhosa people (SAX) study in South Africa. Psychol. Med. 50, 1570–1577 (2020).

Baldwin, J. R., Coleman, O., Francis, E. R. & Danese, A. Prospective and Retrospective Measures of Child Maltreatment and Their Association With Psychopathology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.0818 (2024).

Loewy, R. L. et al. Childhood trauma and clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.003 (2018).

Haidl, T. K. et al. Validation of the Bullying Scale for Adults - Results of the PRONIA-study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 129, 88–97 (2020).

Kraan, T., Velthorst, E., Smit, F., de Haan, L. & van der Gaag, M. Trauma and recent life events in individuals at ultra high risk for psychosis: review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 161, 143–149 (2015).

Solmi, M. et al. Meta-analytic prevalence of comorbid mental disorders in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis: the case for transdiagnostic assessment. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 2291–2300 (2023).

Bechdolf, A. et al. Experience of trauma and conversion to psychosis in an ultra-high-risk (prodromal) group. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 121, 377–384 (2010).

Thompson, A. D. et al. Sexual trauma increases the risk of developing psychosis in an ultra high-risk “prodromal” population. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 697–706 (2014).

Varese, F. et al. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy for psychosis (EMDRp): Protocol of a feasibility randomized controlled trial with early intervention service users. Early Inter. Psychiatry 15, 1224–1233 (2021).

Michel, C., Ruhrmann, S., Schimmelmann, B. G., Klosterkotter, J. & Schultze-Lutter, F. Course of clinical high-risk states for psychosis beyond conversion. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 268, 39–48 (2018).

Salazar de Pablo, G. et al. Clinical outcomes in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis who do not transition to psychosis: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 31, e9 (2022).

Rutigliano, G. et al. Persistence or recurrence of non-psychotic comorbid mental disorders associated with 6-year poor functional outcomes in patients at ultra high risk for psychosis. J. Affect Disord. 203, 101–110 (2016).

Petkus, A. J., Lenze, E. J., Butters, M. A., Twamley, E. W. & Wetherell, J. L. Childhood Trauma Is Associated With Poorer Cognitive Performance in Older Adults. J. Clin. Psychiatry 79, https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.16m11021 (2018).

Hjelseng, I. V. et al. Childhood trauma is associated with poorer social functioning in severe mental disorders both during an active illness phase and in remission. Schizophr. Res. 243, 241–246 (2022).

Wu, N. S., Schairer, L. C., Dellor, E. & Grella, C. Childhood trauma and health outcomes in adults with comorbid substance abuse and mental health disorders. Addict. Behav. 35, 68–71 (2010).

Figueira, M. L. & Brissos, S. Measuring psychosocial outcomes in schizophrenia patients. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 24, 91–99 (2011).

Schmidt, S. J. et al. Multimodal prevention of first psychotic episode through N-acetyl-l-cysteine and integrated preventive psychological intervention in individuals clinically at high risk for psychosis: Protocol of a randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Early Inter. Psychiatry 13, 1404–1415 (2019).

van der Gaag, M., van den Berg, D. & Ising, H. CBT in the prevention of psychosis and other severe mental disorders in patients with an at risk mental state: A review and proposed next steps. Schizophr. Res. 203, 88–93 (2019).

Stain, H. J. et al. Impact of interpersonal trauma on the social functioning of adults with first-episode psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 1491–1498 (2014).

European Network of National Networks studying Gene-Environment Interactions in, S. et al. Identifying gene-environment interactions in schizophrenia: contemporary challenges for integrated, large-scale investigations. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 729–736 (2014).

Gayer-Anderson, C. et al. The EUropean Network of National Schizophrenia Networks Studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI): Incidence and First-Episode Case-Control Programme. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 55, 645–657 (2020).

Yung, A. R. et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 39, 964–971 (2005).

Morosini, P. L., Magliano, L., Brambilla, L., Ugolini, S. & Pioli, R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 101, 323–329 (2000).

Tognin, S. et al. The Relationship Between Grey Matter Volume and Clinical and Functional Outcomes in People at Clinical High Risk for Psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. Open 3, sgac040 (2022).

Mallett, R. Sociodemographic schedule (Institute of Psychiatry, 1997).

Velthorst, E. et al. To cut a short test even shorter: reliability and validity of a brief assessment of intellectual ability in schizophrenia-a control-case family study. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 18, 574–593 (2013).

First, M., Spitzer, R., Gibbon, M. & Williams, J. B. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) (New York State Psychiatric Institute Biometrics Research, 1995).

First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W. & Benjamin, L. S. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders, (SCID-II) (American Psychiatric Press, Inc., 1997).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Press Inc, 1994).

Allen, P. et al. Resting Hyperperfusion of the Hippocampus, Midbrain, and Basal Ganglia in People at High Risk for Psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry 173, 392–399 (2016).

Egerton, A. et al. Relationship between brain glutamate levels and clinical outcome in individuals at ultra high risk of psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 2891–2899 (2014).

Allen, P. et al. Functional outcome in people at high risk for psychosis predicted by thalamic glutamate levels and prefronto-striatal activation. Schizophr. Bull. 41, 429–439 (2015).

Catalan, A. et al. Relationship between jumping to conclusions and clinical outcomes in people at clinical high-risk for psychosis. Psychol. Med. 52, 1569–1577 (2022).

Bernstein, D. P. et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abus. Negl. 27, 169–190 (2003).

Bifulco, A., Brown, G. W. & Harris, T. O. Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse (CECA): A Retrospective Interview Measure. Child Psychol. Psychiat 35, 1414–1419 (1994).

Schäfer, M. et al. Lonely in the crowd: Recollections of bullying. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 22, 379–394 (2010).

Bernstein, D. P., Ahluvalia, T., Pogge, D. & Handelsman, L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36, 340–348 (1997).

Walker, E. A. et al. Adult health status of women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect. Am. J. Med. 107, 332–339 (1999).

Bernstein, D. P. F., L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective Self-Report: Manual (Harcourt Brace & Company, 1998).

Salazar de Pablo, G. et al. Probability of Transition to Psychosis in Individuals at Clinical High Risk: An Updated Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 970–978 (2021).

Salazar de Pablo, G. et al. Longitudinal outcome of attenuated positive symptoms, negative symptoms, functioning and remission in people at clinical high risk for psychosis: a meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 36, 100909 (2021).

de Wit, S. et al. Adolescents at ultra-high risk for psychosis: long-term outcome of individuals who recover from their at-risk state. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 24, 865–873 (2014).

Carrion, R. E. et al. Prediction of functional outcome in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 1133–1142 (2013).

Ruengvirayudh, P. & Brooks, G. P. Comparing stepwise regression models to the best-subsets models, or, the art of stepwise. Gen. Linear Model J. 42, 1–14 (2016).

Brew, B., Doris, M., Shannon, C. & Mulholland, C. What impact does trauma have on the at-risk mental state? A systematic literature review. Early Inter. Psychiatry 12, 115–124 (2018).

Shevlin, M., Houston, J. E., Dorahy, M. J. & Adamson, G. Cumulative traumas and psychosis: an analysis of the national comorbidity survey and the British Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Schizophr. Bull. 34, 193–199 (2008).

Spauwen, J., Krabbendam, L., Lieb, R., Wittchen, H. U. & van Os, J. Impact of psychological trauma on the development of psychotic symptoms: relationship with psychosis proneness. Br. J. Psychiatry 188, 527–533 (2006).

Adams, J., Mrug, S. & Knight, D. C. Characteristics of child physical and sexual abuse as predictors of psychopathology. Child Abus. Negl. 86, 167–177 (2018).

McCrory, E., De Brito, S. A. & Viding, E. The link between child abuse and psychopathology: a review of neurobiological and genetic research. J. R. Soc. Med. 105, 151–156 (2012).

Frohberg, J. et al. Early Abusive Relationships-Influence of Different Maltreatment Types on Postpartum Psychopathology and Mother-Infant Bonding in a Clinical Sample. Front Psychiatry 13, 836368 (2022).

De Bellis, M. D. & Zisk, A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 23, 185–222 (2014).

Lippard, E. T. C. & Nemeroff, C. B. The Devastating Clinical Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect: Increased Disease Vulnerability and Poor Treatment Response in Mood Disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 177, 20–36 (2020).

Bremner, J. D. Traumatic stress: effects on the brain. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 8, 445–461 (2006).

Herman, J. P. et al. Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Stress Response. Compr. Physiol. 6, 603–621 (2016).

Hepp, J., Schmitz, S. E., Urbild, J., Zauner, K. & Niedtfeld, I. Childhood maltreatment is associated with distrust and negatively biased emotion processing. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregul 8, 5 (2021).

Schmitz, S. E., Niedtfeld, I., Lane, S. P., Seitz, K. I. & Hepp, J. Negative affect provides a context for increased distrust in the daily lives of individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment. J. Trauma Stress 36, 808–819 (2023).

Kganyago Mphaphuli, L. in Parenting in Modern Societies (ed Teresa Silva) (IntechOpen, 2023).

Haidl, T. et al. Expressed emotion as a predictor of the first psychotic episode - Results of the European prediction of psychosis study. Schizophr. Res. 199, 346–352 (2018).

Ayerbe, L., Perez-Pinar, M., Foguet-Boreu, Q. & Ayis, S. Psychosis in children of separated parents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 63, e3 (2020).

Karhina, K., Boe, T., Hysing, M. & Nilsen, S. A. Parental separation, negative life events and mental health problems in adolescence. BMC Public Health 23, 2364 (2023).

Bos, K. et al. Psychiatric outcomes in young children with a history of institutionalization. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 19, 15–24 (2011).

Stokkebekk, J., Iversen, A. C., Hollekim, R. & Ness, O. Keeping balance”, “keeping distance” and “keeping on with life”: Child positions in divorced families with prolonged conflicts. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 102, 108–119 (2019).

D’Onofrio, B. & Emery, R. Parental divorce or separation and children’s mental health. World Psychiatry 18, 100–101 (2019).

Xerxa, Y. et al. The Complex Role of Parental Separation in the Association between Family Conflict and Child Problem Behavior. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 49, 79–93 (2020).

Misra, S. et al. Early Parental Death and Risk of Psychosis in Offspring: A Six-Country Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 8, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8071081 (2019).

Burrell, L. V., Mehlum, L. & Qin, P. Parental death by external causes during childhood and risk of psychiatric disorders in bereaved offspring. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 27, 122–130 (2022).

Haapea, M., Nordstrom, T., Rasanen, S., Miettunen, J. & Niemela, M. Parental death due to natural death causes during childhood abbreviates the time to a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder in the offspring: A follow-up study. Death Stud. 46, 168–177 (2022).

Peh, O. H., Rapisarda, A. & Lee, J. Childhood adversities in people at ultra-high risk (UHR) for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med., 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171800394X (2019).

Kraan, T. C. et al. Child Maltreatment and Clinical Outcome in Individuals at Ultra-High Risk for Psychosis in the EU-GEI High Risk Study. Schizophr. Bull. 44, 584–592 (2018).

Baker, S. J., Jackson, M., Jongsma, H. & Saville, C. W. N. The ethnic density effect in psychosis: a systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 219, 632–643 (2021).

Becares, L. & Das-Munshi, J. Ethnic density, health care seeking behaviour and expected discrimination from health services among ethnic minority people in England. Health Place 22, 48–55 (2013).

Oduola, S. et al. Change in incidence rates for psychosis in different ethnic groups in south London: findings from the Clinical Record Interactive Search-First Episode Psychosis (CRIS-FEP) study. Psychol. Med. 51, 300–309 (2021).

Morgan, C., Knowles, G. & Hutchinson, G. Migration, ethnicity and psychoses: evidence, models and future directions. World Psychiatry 18, 247–258 (2019).

Jones, C. M., Merrick, M. T. & Houry, D. E. Identifying and Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences: Implications for Clinical Practice. JAMA 323, 25–26 (2020).

Jorm, A. F. & Mulder, R. T. Prevention of mental disorders requires action on adverse childhood experiences. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 52, 316–319 (2018).

Varese, F. et al. Trauma-focused therapy in early psychosis: results of a feasibility randomized controlled trial of EMDR for psychosis (EMDRp) in early intervention settings. Psychol. Med. 54, 874–885 (2024).

Mitchell, S., Shannon, C., Mulholland, C. & Hanna, D. Reaching consensus on the principles of trauma-informed care in early intervention psychosis services: A Delphi study. Early Inter. Psychiatry 15, 1369–1375 (2021).

Adams, R., Ohlsen, S. & Wood, E. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) for the treatment of psychosis: a systematic review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 11, 1711349 (2020).

van den Berg, D. P. et al. Prolonged exposure vs eye movement desensitization and reprocessing vs waiting list for posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with a psychotic disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 259–267 (2015).

Deleuran, D. H. K., Skov, O. & Bo, S. Prolonged Exposure for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Patients Exhibiting Psychotic Symptoms: A Scoping Review. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 31, e3027 (2024).

Nishith, P., Morse, G. & Dell, N. A. Effectiveness of Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD in serious mental illness. J. Behav. Cognit. Therapy 34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbct.2024.100486 (2024).

Peters, E. et al. Multisite randomised controlled trial of trauma-focused cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis to reduce post-traumatic stress symptoms in people with co-morbid post-traumatic stress disorder and psychosis, compared to treatment as usual: study protocol for the STAR (Study of Trauma And Recovery) trial. Trials 23, 429 (2022).

Jackson, A. L., Frederico, M., Cleak, H. & Perry, B. D. Interventions to Support Children’s Recovery From Neglect-A Systematic Review. Child Maltreat, https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595231171617 (2023).

Levey, E. J. et al. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of interventions designed to decrease child abuse in high-risk families. Child Abus. Negl. 65, 48–57 (2017).

Valadez, E. A. et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Parenting Intervention During Infancy Alters Amygdala-Prefrontal Circuitry in Middle Childhood. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 63, 29–38 (2024).

Hardt, J. & Rutter, M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 45, 260–273 (2004).

Tajima, E. A., Herrenkohl, T. I., Huang, B. & Whitney, S. D. Measuring child maltreatment: a comparison of prospective parent reports and retrospective adolescent reports. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 74, 424–435 (2004).

Ellis, B. J., Sheridan, M. A., Belsky, J. & McLaughlin, K. A. Why and how does early adversity influence development? Toward an integrated model of dimensions of environmental experience. Dev. Psychopathol. 34, 447–471 (2022).

Fareri, D. S. & Tottenham, N. Effects of early life stress on amygdala and striatal development. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 19, 233–247 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants who took part in the study.

Funding

The European Network of National Schizophrenia Networks Studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) Project is funded by grant agreement HEALTH-F2-2010-241909 (Project EU-GEI) from the European Community Seventh Framework Programme. Additional support was provided by a Medical Research Council Fellowship to M Kempton (grant MR/J008915/1). C.A. is supported by the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation. B.N. is supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (1137687). N Barrantes-Vidal was supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación e Universidades (PSI2017-87512-C2-1-R; PID2020-119211RB-I00) and the Generalitat de Catalunya (2021SGR01010 and ICREA Academia Award). E.V. is funded by the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. This manuscript represents independent research partly funded by the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Stefania Tognin (Conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft), Ana Catalan (Conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft), Claudia Aymerich (Writing – review and editing), Anja Richter (Methodology, data curation), Matthew J Kempton (Methodology, data curation), Gemma Modinos (Data acquisition, data curation), Ryan Hammoud (Data curation), Iñigo Gorostiza (Data curation), Evangelos Vassos (Review and editing), Mark van der Gaag (Recruiting, data acquisition, data curation), Lieuwe de Haan (Recruiting, data acquisition, data curation), Barnaby Nelson (Recruiting, Conceptualization, data curation), Anita Riecher-Rössler (Recruiting, data acquisition, data curation), Rodrigo Bressan (Recruiting, data acquisition, data curation), Neus Barrantes-Vidal (Recruiting, data acquisition, data curation), Marie-Odile Krebs (Recruiting, data acquisition, data curation), Merete Nordentoft (Recruiting, data acquisition, data curation), Stephan Ruhrmann (Recruiting, data acquisition, data curation), Gabriele Sachs (Recruiting, data acquisition, data curation), Bart P.F. Rutten (Recruiting, data acquisition, data curation), The EU-GEI High Risk Study (Conceptualization, data acquiring, data curation), Lucia Valmaggia (Conceptualization, Recruiting, data acquisition, Supervision, writing – review and editing), Philip McGuire (Conceptualization, Recruiting, data acquisition, Supervision, writing – review and editing). All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.C. reports personal fees and grants from Janssen-Cilag, ROVI, and Otsuka-Lundbeck outside the submitted work. C.A. reports personal fees and grants from Janssen-Cilag and Neuraxpharm outside the submitted work. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Ethical approval

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tognin, S., Catalan, A., Aymerich, C. et al. Association between Adverse Childhood Experiences and long-term outcomes in people at Clinical High-Risk for Psychosis. Schizophr 11, 23 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00562-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00562-9