Abstract

Extrinsic reward and intrinsic motivation jointly influence memory. While studies show that rewards diminish the effect of intrinsic motivation on memory, rewards usually precede intrinsic motivation, leaving a gap in understanding their interaction when rewards are presented afterward. So, this study investigated how the timing of reward cues moderated the interaction between reward and intrinsic motivation on memory over time. Participants viewed film clips, rated interest, and completed memory tests at different delays. Reward cues were presented either before or after each clip and rating. Results showed that when cued before clips, rewards improved memory and attenuated forgetting for low-interest clips, thereby decreasing the interest effect on memory. Conversely, when cued after clips, rewards improved memory and attenuated forgetting for high-interest clips, thereby increasing the interest effect. Both patterns emerged through time-dependent consolidation. These findings clarify how extrinsic reward and intrinsic motivation interact across temporal dynamics to influence memory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Motivation is an important drive of individual behavior, including learning and memory. Stronger motivation, either due to extrinsic rewards such as food and money, or intrinsic motivation such as curiosity and interest, leads to enhanced memory performance1,2,3,4. On the other hand, daily activities are not driven by a single motivation. For instance, students work hard not only due to their desire to gain higher scores in courses, but also due to their interest in and enjoyment of exploring and obtaining new knowledge. The two types of motivation interact to influence memory and decision-making5,6. How to effectively take advantage of extrinsic reward to enhance memory is an issue with theoretical and practical significance.

A notable phenomenon for the interaction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation is the undermining effect5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Studies have shown that providing extrinsic reward contingent upon task performance, as opposed to providing no reward, decreases the intrinsic appeal of the task7. The undermining effect also extended to memory domain12,13,14. In a study of Murayama and Kuhbandner12, participants viewed trivia questions that varied in interest levels. Half of the participants were given a monetary reward when they guessed correctly, while the other half were not. The results showed a significant interaction between interest and reward at 1 week. Compared to those in the no-reward group, participants in the reward group showed non-significant memory enhancement for interesting questions, while their memory for uninteresting questions was significantly enhanced12.

The undermining effect is typically explained by the self-determination theory, which assumes that as an external controller, extrinsic reward destroys intrinsic motivation by reducing behavior autonomy6,11,15. Accordingly, when extrinsic rewards are administered before an intrinsically motivated task, individuals perceive the rewards as controlling and consequently engage in tasks primarily for rewards rather than their inherent interest16,17, thereby decreasing the interest effect on task performances. This crowding-out effect of intrinsic motivation also accounts for the interaction between reward and intrinsic motivation on memory performance12,13,14. That is, rewards weaken memory enhancement effect of intrinsic motivation13,14, or in another direction, the effect of reward on memory is diminished when intrinsic motivation is high12.

On the other hand, extrinsic rewards do not always weaken intrinsic motivation on task performance5,6,7,18 or memory19,20. Previous studies have shown that compared to rewards provided beforehand, rewards provided after tasks do not decrease intrinsic motivation8,10,21,22, or even increase it when the initial interest is high23. In such scenarios, individuals are unaware of potential rewards when they perform the tasks, thus they are less likely to perceive their behaviors as externally controlled and their intrinsic motivation is preserved. In a memory study20, when rewards were delayed as presented during trivia answers rather than during questions, the results showed independent effects of reward and curiosity on memory at 1 week, which also differed from those where reward cues were presented before tasks12,13,14.

As shown in the meta-analysis studies5,6, controlling or direct rewards tend to weaken the effect of intrinsic motivation, whereas less controlling or indirect rewards may preserve or even enhance intrinsic motivation8,10,21,22,23. Based on this framework, we propose that manipulating the timing of reward cues influences the controlling quality of extrinsic reward, alters the relative priority of reward and intrinsic motivation, and in turn modulates the allocation of encoding resources during memory formation. Specifically, when reward cues are presented before stimuli, individuals are explicitly aware of which stimuli would be rewarded. In this case, reward acts as a controlling factor that enhances the salience of rewarded stimuli and directly facilitates their encoding24,25, leading to improved memory even for low-interest stimuli. In contrast, when reward cues are presented after stimuli, individuals do not know which stimuli would be rewarded during encoding. In this case, intrinsic motivation remains unaffected by extrinsic rewards8,10,21,22, allowing intrinsic motivation to dominate the encoding process and prioritize high-interest stimuli. However, direct empirical evidence on how post-stimulus rewards and intrinsic motivation jointly influence memory encoding remains limited.

Moreover, selective consolidation may be important for the interaction between extrinsic reward and intrinsic motivation on memory. Studies have suggested that selective consolidation is more pronounced for memory associated with reward26,27. The undermining effect on memory is also observed at delayed tests12,13,14. The information with rewards or high intrinsic motivation can be tagged as salient, because such information is prioritized for future adaptive behavior28,29,30, thereby enabling sleep-dependent consolidation31,32. When reward cues are presented before stimuli, those associated with reward are tagged as salient and important, but not all of them can be strongly encoded due to limited resources. In such cases, weakly encoded but tagged stimuli rely more on sleep-dependent consolidation33,34,35. In contrast, when reward cues are presented after stimuli, those with high intrinsic motivation are tagged as salient. Subsequent rewards retroactively reassess the importance of these stimuli27,36, additively enhancing their selective consolidation.

In sum, the current study investigated how the timing of reward cues moderated the interaction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on memory over time. Participants viewed film clips and rated their interest after each clip. Reward cues, which indicated whether clips were rewarded or not, were presented either before (Experiment 1) or after (Experiment 2) the clip and rating. Short film clips were used because they are vivid and vary in interest for individuals, closely mimicking naturalistic experiences in daily lives37,38,39,40. Median split analyses were used to classify the interest levels (high, low)4,20. In order to examine the interaction of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on memory over time, memory was tested at two delays in both experiments (10 min [immediate] and 1 day), with an additional 1-week delay included for Experiment 112,20.

Memory accuracy was analyzed as a primary dependent variable. It was calculated as the proportion of correct responses with high confidence out of all responses. In addition, the forgetting rate and interest effect were employed to clarify complex interactions on accuracy. Forgetting rate, as an index of consolidation41,42,43, was used to clarify how the interaction between reward and interest on memory changed over time. It was calculated as the accuracy difference between the immediate and delayed tests, divided by the accuracy of the immediate test. Interest effect was used to connect the effect of interest on memory with the typical undermining effect and was calculated as the accuracy difference between high- and low-interest conditions. The main differences between the two experiments were the use of before- or after-clip reward cues, and three or two delays employed to test memory.

We hypothesized that the timing of reward cues would influence the priority in memory encoding and adaptive consolidation. Thus, when reward cues are presented before clips12,13,14, rewards would improve memory and attenuate forgetting for low-interest clips. Thus, rewards decrease the interest effect, and an undermining effect would appear. Conversely, when reward cues are presented after clips, rewards would improve memory and attenuate forgetting for high-interest clips. Thus, rewards increase the interest effect, and an additive effect would appear.

Results

Interactive effect when reward cues were presented before the clips

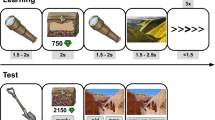

To replicate the interactive effect observed in previous studies12,13,14, reward cues were presented before the participants viewed the film clips and rated their interest levels in Experiment 1 (Fig. 1a). Memory performance was tested 10 mins, 1 day and 1 week after the encoding. A repeated-measures ANOVA with factors of reward (reward, no reward), interest (high, low), and delay (10 min, 1 day, 1 week) revealed significant main effects of reward (F (1, 40) = 13.06, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.25), interest (F (1, 40) = 56.21, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.58), and delay (F (2, 80) = 186.94, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.82). The participants showed better memory performance when the clips were rewarded, more interesting or tested at shorter delays (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 1a). As predicted, there was a significant interaction between reward and interest (F (1, 40) = 7.77, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.16). Post-hoc analysis revealed that high-interest clips were better remembered than low-interest clips in both reward (p < 0.001) and no-reward conditions (p < 0.001). In another direction, the clips with rewards were better remembered than those without rewards (i.e., reward effect) for low-interest clips (p < 0.001) but not for high-interest clips (p = 0.12).

a In Experiment 1, a reward cue (gold coin or gray round) was first presented, followed by a film clip title and the corresponding clip. Then, the participants rated their interest level in this clip. b In Experiment 2, a film clip title and the corresponding clip were first presented, followed by the interest rating. The reward cue was presented afterwards.

a Memory accuracy in each condition in Experiment 1. Memory accuracy was significantly higher for reward vs. no-reward conditions when the participants had low interest in the clips, but not when they had high interest at 1 day. This pattern was not obvious at 10 min and 1 week. b Memory accuracy in each condition in Experiment 2. Memory accuracy was significantly higher for reward vs. no-reward conditions when the participants had high interest in the clips, but not when they had low interest at 1 day. This pattern was not obvious at 10 min. Individual data points are shown as dots, with error bars representing the standard error of the mean (SEM). ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01.

In addition, the interaction between reward and delay was significant (F (2, 80) = 4.10, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.09). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the reward effect (i.e., reward > no reward) was significant at 10 minutes (p < 0.001) and 1 day (p = 0.007), but was not significant at 1 week (p = 0.54). Based on these results, although the three-way interaction among reward, interest, and delay was not significant (F (2, 80) = 2.35, p = 0.10, ηp2 = 0.06), it is interesting to conduct an exploratory analysis to clarify this three-way interaction when only two delays were included (10 min, 1 day).

In the ANOVA with reward, interest, and two delays (10 min, 1 day) as factors, the three-way interaction among reward, interest, and delay was significant (F (1, 40) = 5.23, p = 0.03, ηp2 = 0.12). Post-hoc analysis showed that rewards improved memory for low-interest clips (p < 0.001) but not for high-interest clips (p = 0.81) at 1 day, but the pattern was not observed at 10 minutes, where rewards improved memory for both high- and low-interest clips (p’s < 0.05). In addition, the main effects of reward, interest, delay, and the interaction between reward and interest were significant (p’s < 0.05). The results highlight the role of overnight consolidation in the reward-interest interaction on memory.

Interactive effect when reward cues were presented after the clips

To temporally separate the timing of reward from interest, and explore the predicted additive effect on memory over time, reward cues were presented after the participants viewed the clips and rated their interest in Experiment 2 (Fig. 1b). Memory performance was tested at 10 min and 1 day due to non-significant reward effect at 1 week in Experiment 1. Similarly, the ANOVA with factors of reward (reward, no reward), interest (high, low), and delay (10 minutes, 1 day) revealed significant main effects of reward (F (1, 41) = 5.18, p = 0.03, ηp2 = 0.11), interest (F (1, 41) = 65.73, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.62), and delay (F (1, 41) = 36.44, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.47). The participants showed better memory performance when the clips were rewarded, more interesting or tested at 10 min (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1b).

Importantly, the interaction between reward and interest was significant (F (1, 41) = 4.56, p = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.10). Post-hoc analysis showed that high interest significantly improved memory for both reward and no-reward conditions (p’s < 0.001). Different from that in Experiment 1, the clips with rewards were better remembered than those without rewards for high-interest clips (p = 0.004), but the effect of reward was not significant for low-interest clips (p = 0.92). The three-way interaction among reward, interest, and delay was also significant (F (1, 41) = 6.64, p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.14). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the reward effect on memory was significant only for high-interest clips at 1 day (p < 0.001). Other interactions were not significant (p’s > 0.05).

Collectively, when reward cues were presented after clips in Experiment 2, a different interactive effect was observed. These findings suggest that the timing of reward cues plays an important role in moderating the interaction between reward and interest on memory over time.

Timing of reward cues influenced the interaction between reward and interest

To further clarify how the timing of reward cues moderated the interaction between reward and interest on memory over time, we first conducted an ANOVA for the primary dependent variable - memory accuracy, then clarified the complex interactions on accuracy by ANOVAs for the forgetting rate and the interest effect (see Methods for details). The experiment/timing of reward cues (Experiment 1, Experiment 2) was included as a between-subjects factor, and 1-week delay in Experiment 1 were excluded to maintain temporal comparability across experiments.

For memory accuracy, an ANOVA was conducted with experiment (Experiment 1, Experiment 2), reward (reward, no reward), interest (high, low), and delay (10 min, 1 day) as factors (Supplementary Table 1). Importantly, the four-way interaction was significant (F (1, 81) = 11.59, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.13). Post-hoc analysis showed that at 1 day, when reward cues were presented before clips, the reward effect on memory was only significant for low-interest clips (p < 0.001), but not significant for high-interest clips (p = 0.62). However, this pattern was not observed at 10 min, with reward improving memory for both low- (p = 0.001) and high-interest (p < 0.001) clips. In contrast, when reward cues were presented after clips, the reward effect was significant for high-interest clips (p = 0.005), but not significant for low-interest clips (p = 0.40) at 1 day. This pattern was not observed at 10 min, with reward showing no memory improvement for either high- (p = 0.45) or low-interest (p = 0.50) clips. These results suggest that the timing of reward cues modulates interactions between reward and interest in memory over time, and the interactive effects need time to consolidate.

Accordingly, the three-way interaction among experiment, reward, and interest was significant (F (1, 81) = 13.53, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.14) (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 2a). Post-hoc analysis revealed that when reward cues were presented before clips, reward (vs. no reward) improved memory for low-interest clips (p < 0.001) more obviously than for high-interest clips (p = 0.01). In contrast, when reward cues were presented after clips, reward significantly improved memory for high-interest clips (p = 0.01), but not for low-interest clips (p = 0.94). We also observed a significant two-way interaction between experiment and reward (F (1, 81) = 7.76, p = 0.007, ηp2 = 0.09). Post-hoc analysis showed that the reward effect was significant in Experiment 1 (p < 0.001), but not in Experiment 2 (p = 0.13). In addition, the interaction between experiment and delay was significant (F (1, 81) = 7.43, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.08). Post-hoc analysis showed that although memory accuracy significantly declined in both experiments (p’s < 0.001), there was a greater memory decline in Experiment 1 (MD = 0.18) compared to Experiment 2 (MD = 0.11). No other significant interactions were observed (p’s > 0.05). The main effects of reward, interest, and delay were significant (p’s < 0.05), but the main effect of the experiment was not (p = 0.78).

a Rewards (vs. no rewards) improved accuracy for low-interest clips more obviously when reward cues were presented before clips. However, rewards improved accuracy for high-interest clips when reward cues were presented after clips. Memory accuracy was averaged across two delays (10 min and 1 day) in each experiment. b Rewards attenuated the forgetting for the low-interest clips but increased the forgetting for the high-interest clips when reward cues were presented before clips. However, rewards attenuated the forgetting for the high-interest clips when reward cues were presented after clips. Individual data points are shown as dots, with error bars representing the SEM. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Forgetting rate

To elucidate the four-way interaction of accuracy, an ANOVA for the forgetting rate was conducted, with experiment (Experiment 1, Experiment 2), reward (reward, no reward), and interest (high, low) as factors (Supplementary Table 2). The forgetting rate, which inherently incorporated the factor of delay in its calculation while controlling for the initial performance, could better demonstrate accuracy change over time. The results revealed a significant three-way interaction on the forgetting rate (F (1, 78) = 19.13, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.20) (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 2b), which mirrored the four-way interaction on accuracy. Post-hoc analysis showed that when the reward cues were presented before clips, rewards decreased the forgetting rate for the clips with lower interest (p = 0.003), and increased the forgetting rate for the clips with higher interest (p = 0.01). In contrast, when reward cues were presented after clips, the reward effect on the forgetting rate occurred for the clips with higher interest (p = 0.04), but not for those with lower interest (p = 0.28). No other interactions and main effects were significant (p’s > 0.05). These results consistently suggest that the timing of reward cues is important for the interaction of reward and interest on memory change over time.

Interest effect

To better understand how the timing of reward cues moderated the interactive effects, and connect the memory effect with the typical undermining effect7,9, an ANOVA on the interest effect (i.e., accuracy difference between high- and low-interest conditions) was conducted, with experiment (Experiment 1, Experiment 2), reward (reward, no reward), and delay (10 minutes, 1 day) as factors (Supplementary Table 3). Consistent with the four-way interaction on accuracy, results showed a significant three-way interaction among experiment, reward, and delay on the interest effect (F (1, 81) = 11.52, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.12) (Fig. 4a). Post-hoc analysis showed that when reward cues were presented before clips, the interest effect was significantly weaker under reward than no-reward conditions at 1 day (p < 0.001), evidenced as a typical undermining effect. However, the interest effect was not influenced by reward at 10 minutes (p = 0.65). In contrast, when reward cues were presented after clips, the interest effect was significantly stronger under reward than no-reward conditions at 1 day (p = 0.002), but not significant at 10 min (p = 0.93). Accordingly, there was a significant two-way interaction between experiment and reward (F (1, 81) = 13.51, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.14) (Fig. 4b), showing that rewards decreased the interest effect when cued before clips (p = 0.003), but increased the interest effect when cued after clips (p = 0.03). No other interactions and main effects were significant (p’s > 0.05). The results highlighted that the timing of reward cues moderates the influence of reward on the interest effect, which relies on the time-dependent consolidation.

a At 1 day, rewards decreased the interest effect on memory when reward cues were presented before clips, but increased the interest effect when reward cues were presented after clips. The patterns were not observed at 10 min. b The interest effect was weaker for rewarded than non-rewarded clips when reward cues were presented before clips, but was stronger when reward cues were presented after clips. Individual data points are shown as dots, with error bars representing the SEM. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Control analysis for interest rating

To confirm that the reward manipulation did not influence interest ratings, an ANOVA for the interest rating was performed, with experiment (Experiment 1, Experiment 2), reward (reward, no reward), interest (high, low), and delay (10 min, 1 day) as factors. There was a significant interaction between experiment and interest (F (1, 81) = 22.28, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.22). Post-hoc analysis showed that the interest ratings were comparable in two experiments in the high-interest condition (p = 0.36), but they were significantly higher in Experiment 1 than in Experiment 2 in the low-interest condition (p < 0.001) (Fig. 5). The results suggest that presenting reward cues before clips (vs. after clips) increases the interest levels for low-interest clips. Additionally, the influence of experiment was significant (F (1, 81) = 8.01, p = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.09), showing a higher interest rating when reward cues were presented before clips (vs. after clips). Moreover, the effect of interest was significant (F (1, 81) = 645.60, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.89), indicating clear separation between high- and low-interest conditions. Note that all the main effects and interactions related to reward or delay were not significant (p’s > 0.05). These results confirmed that participants’ interest rating was not influenced by reward and delay conditions in each experiment, and the median split group analysis effectively separated high- and low-interest levels.

Discussion

By manipulating the timing of reward cues, our study found that the interaction between extrinsic reward and intrinsic motivation on memory was significantly altered over time. Particularly, when reward cues were presented before clips, rewards improved memory and attenuated forgetting of the clips with lower interest, thereby decreasing the interest effect on memory. In contrast, when reward cues were presented after clips, rewards improved memory accuracy and attenuated forgetting of the clips with higher interest, thereby increasing the interest effect. The interactive effects on accuracy and the interest effect were observed at 1 day, but not at 10 min, which aligned with the results of the forgetting rate, suggesting an important role of the time-dependent consolidation. These results collectively revealed how extrinsic reward and intrinsic motivation interact across temporal dynamics to influence memory and retention.

Consistent with previous studies12,13,14, the results of Experiment 1 showed a significant interactive effect at 1 day when the reward cues were presented before clips, with rewards selectively enhancing memory for low-interest clips but not for high-interest clips. Importantly, rewards reduced the interest effect on memory at 1 day, revealing an undermining effect in the memory domain. The results support the view that extensive overlaps in the cognitive mechanisms underlie both extrinsic reward and intrinsic motivation at memory encoding4,9,44,45, creating potential competition for limited resources14,20. Thus, when rewards are perceived as controlling, they effectively crowd out the interest effect on memory12,13,14. Note that a previous study observed this effect at 1 day13,14 or 1 week12. However, as memory was tested13,14 or analyzed12 for the interactive effect of reward and interest at only one delay, they could not delineate the time changes of the interactive effect. By including various delays in the analysis, our study extends previous findings in that the interactions between reward and interest, and the influence of reward on the interest effect are significant at 1 day but not at 10 min in Experiment 1. In addition, rewards attenuated forgetting for low-interest clips, but increased forgetting for high-interest clips. These results consistently provide evidence that the undermining effect is time-dependent and requires sleep-associated consolidation.

One interesting issue is understanding the undermining effect on memory. The term of “undermining effect” was traditionally used to describe the phenomenon that extrinsic reward for an initially enjoyable task reduces subsequent intrinsic motivation for the task6,16. For example, participants in the reward group exhibited significantly fewer voluntary behaviors compared to the control group7,9. In line with this idea, we interpreted the reward-interest interaction on accuracy in Experiment 1 by calculating the interest effect (i.e., the accuracy difference between high- and low-interest conditions), and found that the interest effect was significantly decreased by reward (vs. no reward) at 1 day but not at 10 min. Therefore, the terminology of “undermining effect” maintains conceptual continuity with prior studies, and broadens the scope of undermining effect in memory field12,13,14. On the other hand, it is true that when examining only the high-interest condition, memory accuracy did not differ between reward and no-reward conditions. We consider that the unique characteristics of memory processes, such as attention allocation, selective consolidation and retrieval efforts, may counteract the typical undermining effect of extrinsic reward on intrinsic motivation for memory tasks, as also discussed in detail in the previous study12.

One novel finding of our study was that the additive effect of extrinsic reward and intrinsic motivation appeared when reward cues were applied after the clips. The additive effect has two important features. First, the reward-related memory enhancement appeared for the clips with higher interest, but not for those with lower interest. Second, the additive effect was significant at 1 day but not at 10 min, as evidenced by the findings on both memory accuracy and the interest effect. The results suggest that interest and reward could work independently19,20, and their underlying mechanisms complement each other, leading to an additive effect that promotes subsequent memory. When reward cues are presented after the clips, intrinsic motivation guides the encoding process, and the subsequent reward selectively enhances memory of high-interest clips through post-encoding consolidation29,46. This aligns with prior findings that post-encoding reward selectively improves memory for previously encoded items that are conceptually27,47 or spatiotemporally36 related to reward, while further extending this effect to motivationally relevant items.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that manipulates the timing of reward cues and examines their influence on reward-interest interactions on memory over time. This manipulation determines whether reward-associated or interest-associated information is prioritized during encoding, thereby modulating processes such as how to allocate attention/encoding resources and which type of information is selected for subsequent consolidation. The results are consistent with the framework, indicating that the interaction of extrinsic reward and intrinsic motivation is moderated by controlling (vs. less controlling) quality of rewards5,6. Specifically, reward cues before clips make extrinsic reward dominant, prioritizing encoding of rewarded even low-interest clips, while reward cues after clips allow high interest to guide the encoding process3,4,48,49. Therefore, by changing the controlling quality of rewards, the timing of reward cues determined whether rewarded or high-interest clips are salient and prioritized during encoding.

Moreover, the four-way interaction for accuracy and the three-way interaction for the interest effect revealed that both the undermining and additive effects were significant at 1 day but not at 10 min. These findings were confirmed by the significant three-way interaction for the forgetting rate, showing that the interactive effects were time-dependent and relied on consolidation. These features are consistent with the dopaminergic memory consolidation hypothesis32 and the adaptive memory consolidation framework28, which propose that the prioritized information, whether reward-associated, future-relevant, or semantic-related, undergoes a selective consolidation process. Specifically, when reward cues are presented before clips, as not all of the rewarded clips are strongly encoded, sleep-dependent consolidation rescues memory of those tagged as salient but weakly encoded33,34,35, i.e., clips with low interest. In contrast, when reward cues are presented after clips, high-interest stimuli have priority to be encoded, and subsequent reward cues retroactively27,47 reinforce the importance of high-interest stimuli, resulting in improved accuracy and attenuated forgetting for them. The results emphasized a crucial role of adaptive consolidation in effective interactions of reward and interest, and furthermore, of the bias toward the retention of prioritized features.

Taken together, our study has significant theoretical implications. The findings complement and extend our knowledge about interactions of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on memory over time. In addition to the undermining effect, extrinsic reward and intrinsic motivation could additively enhance memory by reducing the controlling quality of rewards, changing priority in memory encoding, and facilitating selective consolidation. The findings also provide clear evidence on how memory is established and maintained in complex motivational contexts where reward and intrinsic motivation coexist. That is, only prioritized information is selectively retained and stabilized over time to support flexible and adaptive memory28,32.

From a practical perspective, there are many things and events that are inherently interesting in our lives. How to effectively utilize extrinsic rewards based on one’s intrinsic motivation is an important issue. Our results provide a novel approach to enhancing memory by utilizing reward and intrinsic motivation in their temporal dynamics. For example, when students already possess a high level of interest in a course, pre-learning extrinsic rewards may be unnecessary. Instead, unexpected rewards given after learning could help further improve their performance. Conversely, when students lack intrinsic motivation to learn a course, promising rewards linked to their performance before learning could boost their engagement. Furthermore, these strategies could be applied to other workplaces by considering both reward and intrinsic motivation.

This study has several limitations that need further investigation. First, we manipulated reward and delay as within-subjects factors and timing of reward cue as a between-subjects factor, and applied intentional memory instructions in this study. Although these manipulations are effective, alternative experimental designs12,13,14 could provide additional insights. Second, unlike previous studies that used trivia questions, which allowed pre-experimental curiosity/interest evaluations13,19, our clip titles lacked sufficient information for participants to evaluate their interest in the clips. So, although the title interest levels were controlled across conditions and ANOVA results supported the independence of reward and interest rating in clips in our study, future studies could use other material types, such as trivia questions, to replicate current findings. Third, we did not observe a significant interactive effect at 1 week in Experiment 1, as in a previous study12. The discrepancy may be attributed to differences in the reward manipulation, learning approach, and material type, which need further investigation. For example, the retrieval-based learning approach may boost subsequent memory and consolidation50,51,52, leading to a significant interactive effect at 1 week. Fourth, in addition to the timing of reward cues, whether the interactive effect on memory is influenced by other factors, such as memory strength and memory type, and which prioritized information is further consolidated, needs future investigations via electrophysiology or neuroimaging technologies.

In conclusion, our study not only confirmed and extended the findings on the different interactive effects of reward and interest on memory over time, but also clarified the crucial role of reward cue timing in moderating the directions of their interactions. Notably, memory enhancement was manifested for clips of lower interest when the reward was cued before the clips, whereas for clips of higher interest when the reward was cued after the clips. The patterns emerged only after consolidation and were absent at immediate tests. These results deepen our understanding of the mechanisms involved in the interaction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation and emphasize the important roles of encoding priority and selective consolidation in adaptive memory. They also provide practical guidance on tailoring reward strategies to individuals’ internal states to optimize memory performance.

Methods

Participants

A total of 86 participants were recruited in the study. Half of them participated in Experiment 1 (28 females, age = 20.65 ± 2.05 yrs), and the other half participated in Experiment 2 (29 females, age = 21.30 ± 2.19 yrs). The sample size was determined by a prior sample size estimation using MorePower53. Previous study revealed that the average effect size (ηp2) of a two-way interaction between extrinsic factor and intrinsic motivation on memory was 0.13 (ηp2 = 0.06-0.22)12,14,41. Given that our study examined a higher-order four-way interaction, a conservative estimated effect size of ηp2 = 0.09 was adopted. To achieve 80% power at α = 0.05 for a mixed-design ANOVA with one between-subjects factor (two levels: Experiment 1, Experiment 2) and three within-subjects factors (two levels each: reward, interest, delay), the analysis indicated a required sample size of 84. All the participants had no history of neurological or psychiatric disease and no history of medication use. They were right-handed and fluent in Chinese. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human and Animal Protection of the School of Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, Peking University (Protocol number: 2020-04-08) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All the participants filled out the informed consent form and acknowledged that they would be paid an additional performance-based bonus, along with a baseline payment, before starting the experiment.

Design

In each experiment, there were three within-subjects factors: reward (reward, no reward), interest (high, low) and delay (10 min, 1 day). The 1-week delay was additionally included in Experiment 1.

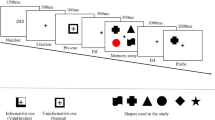

Stimuli

In Experiment 1, 30 film clips were used as stimuli, which were taken from previous studies41,54,55. Each clip was around 25 s in duration with a coherent plot of human activities (e.g., taking photos, cooking breakfast, stealing neckless) and limited dialog. The features of the film clips were evaluated by an independent group of participants (N1 = 24; 12 males, with mean age of 22.29 ± 2.80 yrs), including visual complexity (2.89 ± 0.32), story complexity (2.54 ± 0.34), sound complexity (2.33 ± 0.30), and emotional features (valence 3.02 ± 0.59 and arousal 2.48 ± 0.34) on a 5-point scale (one as the least and five as the most)40,41. In Experiment 2, additional two film clips were added as stimuli to be divisible by four conditions (2 reward * 2 delay), resulting in a total of 32 film clips. The selected film clips exhibited similar properties to those in Experiment 1 with respect to visual complexity (2.88 ± 0.32), story complexity (2.54 ± 0.36), sound complexity (2.32 ± 0.30), valence (3.02 ± 0.58) and arousal (2.47 ± 0.36).

Each clip had a unique title (e.g., “White headscarf”, “Long flute”), which was derived from perceptual information in each of the clip episodes. These titles also served as the encoding and retrieval cues. The reason for choosing perceptual information as the title was based on findings from a previous study, which revealed that the level of interest has a stronger effect on memory enhancements in clips when detailed titles (perceptual-based) were used as memory cues compared to gist titles41. Ten questions for each clip were used during the memory tests (Table 1). These questions were created based on a pilot study (N2 = 10; 9 females, with a mean age of 22.20 ± 2.10 yrs). In the pilot study, participants viewed a total of 73 film clips and were asked to recall both the story content and contextual details immediately after viewing each clip. Based on their descriptions, questions were created to test memory for both the main storyline (e.g., what happened and who did it) and the perceptual information of the clips (e.g., the appearance of a character, the form of an object)40,41. Each question had three options, with one option being the correct answer and the other two options being foils.

To diminish the influence of prior experience of the film clips on memory, the baseline performance (i.e., the probability of accurately answering questions without viewing the film clips) was tested by an independent group of participants (N3 = 16, seven males, with mean age of 21.13 ± 1.93 yrs). The participants were presented with each of clip titles and questions with three options, and were asked to choose one option. The baseline performance was well controlled to a chance level (0.33) (Experiment 1: 0.33 ± 0.07, p = 0.88; Experiment 2: 0.33 ± 0.07, p = 0.83). In addition, before answering the questions, participants rated their interest in the clip titles on a 5-point scale (“How interested are you in the title of the clips?”) (1 = very uninterested, 5 = very interested). The interest in the clip titles was not significantly correlated with the interest in the clips (p’s > 0.05).

In Experiment 1, the clips were first divided into two sets that were used for conditions of reward (reward, no reward), then each set was divided into three subsets that were used for three delays (10 min, 1 day and 1 week), resulting in six subsets in total. For each set, there were five film clips with 50 questions in total. Similarly, in Experiment 2, the clips were first divided into two sets and then divided into four subsets used for conditions of reward (reward, no reward) and delays (10 min, 1 day). For each set, there were eight film clips with 80 questions in total. The features of film clips (e.g., visual complexity, story complexity, sound complexity, emotional content), the number of words for the clip titles, interest in the clip titles, and the baseline performance were matched among all the subsets in each experiment (p’s > 0.05). The clip subsets were counterbalanced across participants using a Latin square design. This approach guaranteed that each clip had an equal chance of being assigned to different conditions.

Procedure

The procedures included the encoding and retrieval phases in both experiments (Fig. 1). The participants learned the film clips during encoding and took memory tests at different delays.

During the encoding phase, in Experiment 1, the participants were first presented with a reward cue (i.e., a gold coin or gray round) for 6 s. They were instructed that “the gold coin represents that remembering the upcoming clip in the memory test could earn a reward of up to ¥5, while the gray round represents no reward for remembering the clip”. Subsequently, the title of the clip (e.g., “White headscarf”) was displayed for 4 s, after which the corresponding clip was played. Then the participants rated their interest in the clip on a 7-point scale, with the instruction: “Please rate how interested are you in the film clip (1 = very uninterested, 7 = very interested)” (Fig. 1a). They were explicitly instructed that “your ratings should reflect your genuine interest and willingness to continue viewing the clips, independent of whether the clips are associated with a reward or not”. For example, an interesting clip featured a thief being proud about his theft but later being caught on surveillance camera; an uninteresting clip featured a pregnant woman buying food at the market with a bamboo basket. An inter-trial interval of 1 s was used, during which the message “Next trial begins” signaled the start of the next trial.

In Experiment 2, the procedure was the same except the following: (1) the participants were first presented with the title and the corresponding film clip, then rated their interest in the clip, and finally were presented with the reward cue for 6 s. (2) the participants were instructed that “the gold coin represents that remembering the previously watched clip in the memory test could earn a reward of up to ¥5, while the gray round represents no reward for remembering the clip” (Fig. 1b). Similarly, the inter-trial interval of 1 s was used before each trial. The film clips were pseudo-randomly presented during encoding so that no more than three clips belonging to the same conditions were presented consecutively.

The procedures of the retrieval phase were identical for the two experiments. The title of the clip being tested was first presented as the retrieval cue for 16 s, during which participants were asked to “visualize the clip in your mind from start to end.” This manipulation enabled the participants to elaborate the story contents and perceptual details as much as possible41. Subsequently, a forced-choice task38,41,56 was performed. The questions related to the same clip were presented, with three answer options provided below and the title provided above. The participants were asked to “choose the correct answer within a time limit of 10 s”. After choosing the answer, participants provided a confidence judgment for their choice on a 6-point scale, with the instruction: “Please rate how confident you are in your choice (1 = least confident, 6 = most confident)”, and the clarification that “this judgment would not affect the extra rewards”. All ten questions for each clip were presented in a predetermined random order to ensure that the questions presented earlier would not affect the participants’ responses to the later questions. Once all the questions for the current clip had been tested, the title and questions for the next clip were presented.

In Experiment 1, one-third of the film clips and corresponding questions were assigned to each of the three delay conditions (10 min, 1 day, and 1 week). In Experiment 2, half of the clips and questions were assigned to the 10 min test and the other half to the 1-day test. This design prevented test repetition effects caused by repeated exposures12,57. The position of the correct answer in the forced-choice task was counterbalanced across the conditions. The clips were also pseudo-randomly presented so that no more than three clips belonging to the same conditions were presented consecutively.

Before the retrieval phase at the 10 min delay, the participants were asked to count backward by seven continuously from 1000 for 5 min as the distractor task to avoid rehearsal of the film contents. Additionally, the participants were given separate opportunities to practice the encoding and retrieval trials before the formal phases.

Data analyses

In both experiments, the participants rated their interest level after they viewed each of the film clips. As the experiments were designed by factorial factors, and the sample sizes were estimated accordingly, each participant’s trials were split into high and low conditions according to that participant’s median interest level4,20 at each reward condition and each delay. The high- and low-interest film clips were evenly divided in the reward and no reward cues conditions, separately. For example, in Experiment 1, we split the five rewarded clips tested at 10 min based on the median of their interest values, and did the same for the five unrewarded clips tested at 10 min. Because there were five clips in each condition (reward * delay) in Experiment 1, one clip with the middle interest level was removed from the analysis (20 questions for each condition) (high interest: 5.61 ± 0.68; low interest: 3.24 ± 0.96). Accordingly, two clips with the middle interest levels were removed from the analysis in Experiment 2 (30 questions for each condition) (high interest: 5.87 ± 0.85; low interest: 2.36 ± 0.83). (We also performed the analysis of removing the middle four clips in Experiment 2 to match the number of questions in the two experiments, and the results were similar).

We performed five types of analyses, i.e., ANOVAs for memory accuracy within each experiment, and ANOVAs for memory accuracy, forgetting rate, interest effect on accuracy, and interest rating across experiments. Memory accuracy in the forced-choice tasks was used as a primary dependent variable. Consistent with findings that rewards preferentially enhance high-confidence memory1,27,58,59 and supported by a film clip study validating high-confidence performance as a reliable memory index38, we focused our analysis on correct responses with high confidence (confidence > 3). Additional analyses were conducted for accuracy using all correct responses and correct responses with low-confidence (confidence < 4) separately. The ANOVA results for all responses (see Supplementary Materials) replicated the main findings observed in high-confidence responses, whereas those for the low-confidence responses did not exhibit the same patterns.

First, separate ANOVAs were conducted for memory accuracy with three within-subjects factors in each experiment. The factors were reward (reward, no reward), interest (high, low), and three delay conditions (10 min, 1 day, 1 week) in Experiment 1. Given the reward effect and the interaction between reward and interest were not significant at 1 week, a follow-up analysis was conducted excluding this time point (retaining only the 10 min and 1-day delays) in Experiment 1. The factors of reward, interest, and delay (10 min, 1 day) were included in the ANOVA of Experiment 2. In addition, linear mixed-effects models were performed with interest as a continuous predictor13. The models predicted memory accuracy (coded as 1 for correct responses with high confidence and 0 otherwise) from reward (no reward as -0.5, reward as 0.5), interest (individually normalized scores), delay (10 min as -0.5, 1 day as 0.5), and their interactions13,60,61, while incorporating random intercepts of participants and random slopes of reward, interest, delay, and their interaction61. The results (see Supplementary Materials) replicated the main findings of the ANOVAs.

Second, to clarify how the timing of reward cues moderated the interaction between reward and interest on memory accuracy, a mixed ANOVA was conducted. This analysis included experiment (Experiment 1, Experiment 2), reward (reward, no reward), interest (high, low), and delay (10 min, 1 day) as factors. Similarly, we incorporated experiment as a fixed factor in a linear mixed-effects model that included reward (no reward: -0.5, reward: 0.5), interest (individually normalized), delay (10 minutes: -0.5, 1 day: 0.5), experiment (Experiment 1: -0.5, Experiment 2: 0.5), and their interactions as fixed effects, with random effects including intercepts of participants and slopes for reward, interest, delay, experiment and their interaction61. The results (see Supplementary Materials) also aligned with findings of the ANOVA.

Third, there was a significant four-way interaction in ANOVA for memory accuracy, which suggests that participants in two experiments have different forgetting patterns. Therefore, the forgetting rate, as a behavioral marker of consolidation42,43, was used to elucidate this interaction and exclude the influence of initial memory performance on the forgetting patterns. The forgetting rate was calculated following Eq. (1): the accuracy differences between the immediate test (at 10 min) and the delayed test (at 1 day), divided by the immediate accuracy41,42,43

An ANOVA for the forgetting rate was conducted, with experiment (Experiment 1, Experiment 2), reward (reward, no reward), and interest (high, low) as factors.

Fourth, to better clarify the interaction between reward and interest and to align our findings with the typical undermining effect7,9, we quantified the interest effect by the accuracy difference between high- and low-interest conditions, calculated using Eq. (2). This approach focused on the contribution of interest to memory, and allowed us to directly examine the influence of reward on intrinsic motivation. The ANOVA for the interest effect was performed, with experiment (Experiment 1, Experiment 2), reward (reward, no reward), and delay (10 min, 1 day) as factors.

Fifth, to confirm that the pre-experimental designed manipulations (i.e., reward and delay), particularly reward, did not influence interest ratings, an ANOVA was conducted for the interest rating, with experiment (Experiment 1, Experiment 2), reward (reward, no reward), interest (high, low), and delay (10 min, 1 day) as factors.

Two participants in Experiment 1 were excluded from the analysis due to poor memory performance (below 2 SD) and one participant in Experiment 2 was excluded due to misunderstanding the instructions, resulting in 41 participants in Experiment 1 (26 females, age = 20.73 ± 2.06 yrs) and 42 participants in Experiment 2 (28 females, age = 21.31 ± 2.21 yrs). Three participants in Experiment 1 were excluded from the analysis for the forgetting rate. They did not have correct responses with high confidence at 10 min test in the no-reward-low-interest condition, so the forgetting rate was unable to be calculated in this condition. All ANOVAs were performed using SPSS (version 27), with partial eta squared (ηp2) calculated to estimate effect sizes. To control for the Type I error, post-hoc comparisons were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction for all the ANOVA analyses (p < 0.05, two-tailed). The linear mixed-effects models were implemented in R (version 4.2.1) using the lme4 package62 and the lmerTest package63. Data visualization was implemented in R using the ggplot2 package64.

Data availability

The data, materials, and instructions are available at the Open Science Framework and can be accessed at https://osf.io/smy6b/files/osfstorage (in folder Mem.EI).

Code availability

The codes are available at the Open Science Framework and can be accessed at https://osf.io/smy6b/files/osfstorage (in folder Mem.EI).

References

Adcock, R. A., Thangavel, A., Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., Knutson, B. & Gabrieli, J. D. E. Reward-motivated learning: mesolimbic activation precedes memory formation. Neuron 50, 507–517 (2006).

Wittmann, B. C. et al. Reward-related fMRI activation of dopaminergic midbrain is associated with enhanced hippocampus-dependent long-term memory formation. Neuron 45, 459–467 (2005).

Gruber, M. J., Gelman, B. D. & Ranganath, C. States of curiosity modulate hippocampus-dependent learning via the dopaminergic circuit. Neuron 84, 486–496 (2014).

Kang, M. J. et al. The wick in the candle of learning: epistemic curiosity activates reward circuitry and enhances memory. Psychol. Sci. 20, 963–973 (2009).

Cerasoli, C. P., Nicklin, J. M. & Ford, M. T. Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives jointly predict performance: a 40-year meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 140, 980–1008 (2014).

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R. & Ryan, R. M. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol. Bull. 125, 627–668 (1999).

Deci, E. L. Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 18, 105–115 (1971).

Lepper, M. R., Greene, D. & Nisbett, R. E. Undermining children’s intrinsic interest with extrinsic reward: a test of the “overjustification” hypothesis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 28, 129–137 (1973).

Murayama, K., Matsumoto, M., Izuma, K. & Matsumoto, K. Neural basis of the undermining effect of monetary reward on intrinsic motivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 20911–20916 (2010).

Pretty, G. H. & Seligman, C. Affect and the overjustification effect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 46, 1241–1253 (1984).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 54–67 (2000).

Murayama, K. & Kuhbandner, C. Money enhances memory consolidation - but only for boring material. Cognition 119, 120–124 (2011).

Swirsky, L. T., Shulman, A. & Spaniol, J. The interaction of curiosity and reward on long-term memory in younger and older adults. Psychol. Aging 36, 584–595 (2021).

Xue, J. M. et al. The interactive effect of external rewards and self-determined choice on memory. Psychol. Res. 87, 2101–2110 (2023).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61, 101860 (2020).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Brick by brick: the origins, development, and future of self-determination theory. In Advances in Motivation Science (ed. Elliot, A. J.) 111–156 (Elsevier, 2019).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. The general causality orientations scale – self-determination in personality. J. Res. Pers. 19, 109–134 (1985).

Marsden, K. E., Ma, W. J., Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M. & Chiu, P. H. Diminished neural responses predict enhanced intrinsic motivation and sensitivity to external incentive. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Ne. 15, 276–286 (2015).

Duan, H. X., Fernández, G., van Dongen, E. & Kohn, N. The effect of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on memory formation: insight from behavioral and imaging study. Brain Struct. Funct. 225, 1561–1574 (2020).

Halamish, V., Madmon, I. & Moed, A. Motivation to learn. Exp. Psychol. 66, 319–330 (2019).

Greene, D. & Lepper, M. R. Effects of extrinsic rewards on children’s subsequent intrinsic interest. Child Dev 45, 1141–1145 (1974).

Harackiewicz, J. M., Manderlink, G. & Sansone, C. Rewarding pinball wizardry - effects of evaluation and cue value on intrinsic interest. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 47, 287–300 (1984).

Eisenstein, N. Effects of contractual, endogenous, or unexpected rewards on high and low interest preschoolers. Psychol. Rec. 35, 29–39 (1985).

Jang, A. I., Nassar, M. R., Dillon, D. G. & Frank, M. J. Positive reward prediction errors during decision-making strengthen memory encoding. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 719–732 (2019).

Mason, A., Farrell, S., Howard-Jones, P. & Ludwig, C. J. H. The role of reward and reward uncertainty in episodic memory. J. Mem. Lang. 96, 62–77 (2017).

Murayama, K. & Kitagami, S. Consolidation power of extrinsic rewards: reward cues enhance long-term memory for irrelevant past events. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 143, 15–20 (2014).

Patil, A., Murty, V. P., Dunsmoor, J. E., Phelps, E. A. & Davachi, L. Reward retroactively enhances memory consolidation for related items. Learn. Mem. 24, 65–69 (2017).

Cowan, E. T., Schapiro, A. C., Dunsmoor, J. E. & Murty, V. P. Memory consolidation as an adaptive process. Psychon. B. Rev 28, 1796–1810 (2021).

Dunsmoor, J. E., Murty, V. P., Clewett, D., Phelps, E. A. & Davachi, L. Tag and capture: how salient experiences target and rescue nearby events in memory BR. Trends Cogn. Sci. 26, 782–795 (2022).

Mather, M., Clewett, D., Sakaki, M. & Harley, C. W. Norepinephrine ignites local hotspots of neuronal excitation: how arousal amplifies selectivity in perception and memory. Behav. Brain Sci. 39, e200 (2016).

Bennion, K. A., Steinmetz, K. R. M., Kensinger, E. A. & Payne, J. D. Sleep and cortisol interact to support memory consolidation. Cereb. Cortex 25, 646–657 (2015).

Shohamy, D. & Adcock, R. A. Dopamine and adaptive memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14, 464–472 (2010).

Bäuml, K. H. T., Holterman, C. & Abel, M. Sleep can reduce the testing effect: it enhances recall of restudied items but can leave recall of retrieved items unaffected. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 40, 1568–1581 (2014).

Dunsmoor, J. E., Murty, V. P., Davachi, L. & Phelps, E. A. Emotional learning selectively and retroactively strengthens memories for related events. Nature 520, 345–348 (2015).

Lutz, N. D., Albert, E. M., Friedrich, H., Born, J. & Besedovsky, L. Sleep shapes the associative structure underlying pattern completion in multielement event memory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2314423121 (2024).

Braun, E. K., Wimmer, G. E. & Shohamy, D. Retroactive and graded prioritization of memory by reward. Nat. Commun. 9, 4886 (2018).

da Silva Castanheira, K., Lalla, A., Ocampo, K., Otto, A. R. & Sheldon, S. Reward at encoding but not retrieval modulates memory for detailed events. Cognition. 219, 104957 (2022).

Furman, O., Dorfman, N., Hasson, U., Davachi, L. & Dudai, Y. They saw a movie: long-term memory for an extended audiovisual narrative. Learn. Mem. 14, 457–467 (2007).

Furman, O., Mendelsohn, A. & Dudai, Y. The episodic engram transformed: time reduces retrieval-related brain activity but correlates it with memory accuracy. Learn. Mem. 19, 575–587 (2012).

Sekeres, M. J. et al. Recovering and preventing loss of detailed memory: differential rates of forgetting for detail types in episodic memory. Learn. Mem. 23, 72–82 (2016).

Hu, Z. Y. & Yang, J. J. Effects of memory cue and interest in remembering and forgetting of gist and details. Front. Psychol. 14, 1244288 (2023).

Li, C. H., Hu, Z. Y. & Yang, J. J. Rapid acquisition through fast mapping: stable memory over time and role of prior knowledge. Learn. Mem. 27, 177–189 (2020).

Murty, V. P., DuBrow, S. & Davachi, L. Decision-making increases episodic memory via postencoding consolidation. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 31, 1308–1317 (2019).

Lau, J. K. L., Ozono, H., Kuratomi, K., Komiya, A. & Murayama, K. Shared striatal activity in decisions to satisfy curiosity and hunger at the risk of electric shocks. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 531–543 (2020).

Gottlieb, J., Hayhoe, M., Hikosaka, O. & Rangel, A. Attention, reward, and information seeking. J. Neurosci. 34, 15497–15504 (2014).

Lisman, J., Grace, A. A. & Duzel, E. A neoHebbian framework for episodic memory: role of dopamine-dependent late LTP. Trends Neurosci 34, 536–547 (2011).

Oyarzún, J. P., Packard, P. A., de Diego-Balaguer, R. & Fuentemilla, L. Motivated encoding selectively promotes memory for future inconsequential semantically-related events. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 133, 1–6 (2016).

Fastrich, G. M., Kerr, T., Castel, A. D. & Murayama, K. The role of interest in memory for trivia questions: an investigation with a large-scale database. Motiv. Sci. 4, 227–250 (2018).

Marvin, C. B. & Shohamy, D. Curiosity and reward: valence predicts choice and information prediction errors enhance learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 145, 266–272 (2016).

Brod, G. Predicting as a learning strategy. Psychon. B. Rev 28, 1839–1847 (2021).

Pashler, H., Rohrer, D., Cepeda, N. J. & Carpenter, S. K. Enhancing learning and retarding forgetting: choices and consequences. Psychon. B. Rev 14, 187–193 (2007).

Roediger, H. L. & Butler, A. C. The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 20–27 (2011).

Campbell, J. I. D. & Thompson, V. A. MorePower 6.0 for ANOVA with relational confidence intervals and Bayesian analysis. Behav. Res. Methods 44, 1255–1265 (2012).

St-Laurent, M., Moscovitch, M., Jadd, R. & McAndrews, M. P. The perceptual richness of complex memory episodes is compromised by medial temporal lobe damage. Hippocampus 24, 560–576 (2014).

St-Laurent, M., Moscovitch, M. & McAndrews, M. P. The retrieval of perceptual memory details depends on right hippocampal integrity and activation. Cortex 84, 15–33 (2016).

Gellersen, H. M. et al. Medial temporal lobe structure, mnemonic and perceptual discrimination in healthy older adults and those at risk for mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol. Aging 122, 88–106 (2023).

Roediger, H. L. III & Karpicke, J. D. Test-enhanced learning: taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychol. Sci. 17, 249–255 (2006).

Bowen, H. J., Marchesi, M. L. & Kensinger, E. A. Reward motivation influences response bias on a recognition memory task. Cognition 203, 104337 (2020).

Nagel, J. et al. Memory for rewards guides retrieval. Commun. Psychol. 2, 31 (2024).

Fandakova, Y. & Gruber, M. J. States of curiosity and interest enhance memory differently in adolescents and in children. Dev. Sci. 24, e13005 (2021).

Pupillo, F., Ortiz-Tudela, J., Bruckner, R. & Shing, Y. L. The effect of prediction error on episodic memory encoding is modulated by the outcome of the predictions. npj Sci. Learn. 8, 18 (2023).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Soft. 67, 1–48 (2014).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Soft. 82, 1–26 (2017).

Wickham, H., Chang, W. & Wickham, M. H. ggplot2 v2.1 (R Foundation, 2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32071027 to JY).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H. designed the research, performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. J.Y. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Z., Yang, J. Timing of reward cues alters the interaction between reward and interest on memory over time. npj Sci. Learn. 10, 82 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-025-00374-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-025-00374-7