Abstract

Uveal melanoma (UM), the primary intraocular tumor in adults, arises from eye melanocytes and poses a significant threat to vision and health. Despite its rarity, UM is concerning due to its high potential for liver metastasis, resulting in a median survival of about a year after detection. Unlike cutaneous melanoma, UM responds poorly to immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI) due to its low tumor mutational burden and PD-1/PD-L1 expression. Tebentafusp, a bispecific T cell engager (TCE) approved for metastatic UM, showed potential in clinical trials, but the objective response rate remains modest. To enhance TCE efficacy, we explored quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) modeling in this study. By integrating a TCE module into an existing QSP model and using clinical data on UM and tebentafusp, we aimed to identify and rank potential predictive biomarkers for patient selection. We selected 30 important predictive biomarkers, including model parameters and cell concentrations in tumor and blood compartments. We investigated biomarkers using different methods, including comparison of median levels in responders and non-responders, and a cutoff-based biomarker testing algorithm. CD8+ T cell density in the tumor and blood, CD8+ T cell to regulatory T cell ratio in the tumor, and naïve CD4+ density in the blood are examples of key biomarkers identified. Quantification of predictive power suggested a limited predictive power for single pre-treatment biomarkers, which was improved by early on-treatment biomarkers and combination of predictive biomarkers. Ultimately, this QSP model could facilitate biomarker-guided patient selection, improving clinical trial efficiency and UM treatment outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

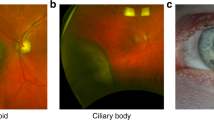

Uveal melanoma (UM), the most common primary intraocular tumor in adults, emerges from melanocytes in the iris, ciliary body, or choroid, and can pose a significant threat to vision and overall health1,2,3. Despite its rarity, UM is a highly concerning malignancy due to its propensity to metastasize, and up to 50% of patients develop metastases most commonly in the liver. The prognosis for those with metastatic disease is bleak, with a median survival of ~1 year after metastases are detected4,5,6.

The remarkable success of immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI) in treating metastatic cutaneous melanoma (CM) generated high hopes for similar benefits in patients with metastatic UM7. Unfortunately, the outcomes of applying these new therapy options to patients with UM were far from promising8,9,10. While both UM and CM originate from melanocytes and share common risk factors, these two melanoma subtypes exhibit significant biological and clinical differences11. Unlike CM, UM is characterized by a low tumor mutational burden (TMB)12,13. Currently, TMB is recognized as one of the most reliable biomarkers for predicting the response to ICI in various tumor types, and UM’s low TMB is considered one of the potential mechanisms for ICI resistance14. Additionally, patients with UM exhibit lower levels of PD-1 and PD-L1 expression compared to those with metastatic CM, which further contributes to the limited effectiveness of ICI mediated by anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies in UM15.

Immunotherapies using bispecific T cell engagers (TCEs), which activate cytotoxic T cells to effectively eliminate cancer cells, have garnered a significant interest in treating patients with UM16. Tebentafusp, formerly known as IMCgp100, is a bispecific antibody designed to target gp100, a protein highly expressed in melanomas, and CD3 on T cells, facilitating the redirection of T cells to eliminate gp100-expressing cancer cells17,18. In vitro experiments have demonstrated tebentafusp’s ability to induce potent and selective killing of antigen-positive cancer cells. Notably, it was found that both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells were directed to lyse gp100+ cancer cells due to activation by tebentafusp19. Throughout various phases of clinical trials, tebentafusp (Kimmtrak®) has shown promising responses with manageable side effects20,21, leading to its FDA approval in 2022 for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic UM in adult patients who are HLA-A*02:01-positive.

Even though the phase 3 trial for the tebentafusp group demonstrated a high disease control rate (46%; 95% CI, 39–52) compared to the control group (27%; 95% CI, 20–36), where single-agent pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, or dacarbazine were used as per the investigator’s choice of therapy, the percentage of patients showing an objective response to tebentafusp therapy remained relatively low, at 9% (95% CI, 6–13)21. Enhancing the benefits of bispecific TCE therapies in the treatment of solid tumors remains a significant challenge in this field. It is crucial to identify predictive biomarkers that can effectively differentiate responders from non-responders, as this could improve the outcomes of clinical trials.

Quantitative system pharmacology (QSP) modeling has been demonstrated as a promising approach to address current challenges in bispecific TCEs and in general biomarker selection22. For instance, Betts et al. introduced a QSP model to quantify and predict the transition from preclinical to clinical stages for a P-cadherin/CD3 DART bsAb23. Another QSP model developed by Van De Vyver et al. was utilized to forecast tumor killing and T cell activation driven by cibisatamab, a CEA/CD3 T cell bispecific antibody as a function of target expression levels24. In a work by Hosseini et al., the QSP modeling was used to support the design of a phase I trial for mosunetuzumab, a CD20/CD3 T cell bispecific. The primary objective of this study was to minimize the risk of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) while retaining efficacy25. Similarly, to further understand the CRS following bispecific dosing in solid tumors, a QSP model was developed and tebentafusp was used as the case study26. Moreover, in the previous studies of our group, the QSP modeling of bispecific TCE was used to investigate predictive biomarkers27,28, optimize combination dose regimens, and explore potential drug synergy29 when cibisatamab (CEA/CD3 T cell bispecific) was used in combination with the PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor, atezolizumab.

In this study, we expanded our previously developed QSP models29,30 with a TCE module to investigate potential biomarkers for patients with UM. To ensure accuracy, the model was calibrated using available experimental data of UM and published clinical data of UM patients’ treatment with tebentafusp. Our QSP model enables the development of a biomarker-guided patient selection process that enhances the efficiency of clinical trials.

Results

Virtual clinical trial of tebentafusp

We developed a QSP model to explore tebentafusp therapy in UM. This QSP model consists of four compartment, each of which represents a distinct component of a patient: central (blood), peripheral (other tissues and organs), tumor, and tumor-draining lymph node (TDLN), Fig. 1 (see “Methods” section for details on model structure). Pharmacokinetics (PK) parameters were fitted to clinical measurements of plasma concentration for tebentafusp following a single 20 μg dose, observed over a 1-week period in the central compartment (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Due to the lack of plasma concentration data for subsequent doses, these estimated PK parameters are based solely on the initial 20 μg dose. However, to evaluate the model’s behavior over the full treatment course, we simulated the predicted plasma and tumor drug concentrations for the complete dosing regimen: 20 μg on day 1, followed by 30 μg on day 8, and 68 μg weekly for up to five cycles (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

The model is divided into four compartments: central, peripheral, tumor, and tumor-draining lymph node, which describe cycles of immune activation in lymph nodes, T cell trafficking to the tumor, killing of cancer cells, immune evasion, and antigen release and lymphatic transport. MHC major histocompatibility complex, nT naïve T cell, aT activated T cell by mAPC that migrated from tumor to the lymph node where they present the antigen to naïve T cells, NO nitric oxide, Arg-I arginase I, Treg regulatory T cell, Teff effector T cell, Th helper T cell, Texh exhausted T cell, MDSC myeloid derived suppresser cells, Mac macrophage, mAPC mature antigen-presenting cell. Cytokine degradation and cellular clearance were omitted in the diagram. Modified from refs. 29,30.

We aimed to reproduce the clinical setting in our model simulations to conduct a virtual clinical trial of tebentafusp following a phase 3 trial for patients with metastatic UM, NCT0307039221. Following the same dosing schedule used in the trial, we performed our simulations with tebentafusp at a dose of 20 μg on day 1, 30 μg on day 8, and 68 μg weekly thereafter for all the virtual patients (VPs). In this clinical trial, a total of 378 patients were randomly assigned to either the tebentafusp group (252 patients) or the control group (126 patients), and the overall response rate was calculated for each group. To have sufficient data for statistical analysis, we conducted the simulations with a higher number of patients. In this study, we started with a virtual cohort of 1500 patients created by the Latin-Hypercube Sampling (LHS) method. Each VP was generated with a random sample of parameter values based on the list of parameters provided in Supplementary Data 2 and 3. Based on the screening rules (initial tumor diameter, range of reported T cells densities, and Teff/Treg ratio), 910 VPs were filtered out and selected for further processing. The overall response rate (ORR) was calculated for VPs following RECIST 1.1, and the parameters with no experimentally reported values were fitted to the outcome of the clinical trial for each category of RECIST, shown in Fig. 2a. We also calculated the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the result of the simulation by randomly sampling 252 VPs from the 910 simulated VPs (number of patients in the tebentafusp group of the clinical trial) 10,000 times, presented as error bars in Fig. 2a.

a Response status comparison between model prediction and clinical results of tebentafusp monotherapy by RECIST 1.1. Model predictions are presented with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals. Rate of response in model-predicted tumor diameter of b 100 randomly selected VPs, c all VPs. Solid line represents the median and the shaded area denotes the median absolute deviation (mad); CR complete response, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease.

In order to visualize the dynamics of individual VPs, we plotted the response status based on RECIST criteria as spider plots, showing both the individual variabilities of patients by randomly selecting 100 VPs in Fig. 2b and the median behavior of the virtual population in Fig. 2c.

We investigated the sensitivity of the percent tumor size change from baseline against the model parameters with a range using partial rank correlation coefficient (PRCC), whose values range between −1 (negative correlation) and +1 (positive correlation), Fig. 3. As the result shows, tumor growth rate was identified at most positively correlated parameter to the precent of tumor size change. Regarding the parameters with negative correlation on the tumor volume, Neo-Ag specific T cell clone was observed as the most sensitive one. Additionally, we used feature ranking methods in the context of machine learning and tested the importance of each parameter on tumor volume using three algorithms of minimum redundancy feature selection (MRMR), F-test, and RReliefF which are included in the feature selection part of Regression Learner App of MATLAB, Supplementary Fig. 2. Similar to the PRCC method, tumor growth rate was selected as the most sensitive parameter predicted by all three methods. However, the relative sensitivity of other parameters was different based on each method, and in general RReliefF method showed the most similar parameter sensitivity analysis to the PRCC method, Supplementary Fig. 2.

As shown in Fig. 4a–f, we chose the six most sensitive factors found using the PRCC method and used waterfall plots to illustrate the model-predicted tumor diameter changes from baseline for all 910 simulated VPs while taking into account one parameter of interest. Based on the cutoff values for each parameter, the patients were separated into two groups. If a patient’s value is lower than the median, it is displayed in blue; otherwise, it is represented in orange. While the low tumor growth rate is the most significant parameter separating responders from non-responders, a larger portion of responders also show lower values of the rate of Teff death by Tregs and higher values of Neo-Ag specific T cell clone. Other parameters like Kd of antigen and rate of T cell exhaustion by cancer cells were evenly distributed between responders and non-responder.

Identification and ranking of potential predictive biomarkers

To investigate the predictive biomarkers that would help with patient identification for tebentafusp therapy, parameters and derived quantities from the QSP model were selected as candidates for the biomarker analysis. The possible biomarkers were identified based on relevant biomarker data for cancer immunotherapy and TCEs, while availability and accessibility of measurement in patients were taken into account. This resulted in 30 biomarker candidates. Some of those selected biomarkers such as initial tumor diameter, gp100 and CD47 expression on cancer cells, and CD3 expression on cytotoxic T cells (presented in Fig. 5) serve as constant model parameters throughout the treatment. However, other biomarkers like tumor purity (the proportion of cancer cells in the tumor tissue to other cells31), immune cell counts in the central (blood) and tumor compartments, cytokine concentrations (presented in Fig. 6) are the emergent properties of model parameter.

Statistical significance is calculated by Wilcoxon test (ns/NS: p > 0.05; *: p < =0.05; ****: p < =0.0001). Box represents the interquartile range (IQR), line within the box indicates the median value of the data, whiskers extend to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 * IQR, outliers are the individual points that fall outside the whiskers. NR non-responder, R responder.

Pre-treatment (day 1), early-treatment (day 8), and post-treatment (day 400) distributions of potential predictive biomarkers in responders and non-responders. Statistical significance is calculated by Wilcoxon test (**: p < =0.01; ***: p < =0.001; ****: p < =0.0001). Box represents the interquartile range (IQR), line within the box indicates the median value of the data, whiskers extend to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 * IQR, outliers are the individual points that fall outside the whiskers. APC antigen-presenting cell, TumorPurity: ratio of cancer cells to all the cells in the tumor compartment, NR non-responder, R responder.

As the first step, statistical comparisons were conducted between the non-responders (SD and PD) and responders (PR/CR) to identify the most significant differences between them. By studying the potential predictive model parameters shown in Fig. 5, Neo-Ag specific T cell clone is the most significant parameter differentiating the responders and non-responders. The distribution of other parameters like initial tumor diameter, CD47, PDL1 and gp100 expression on tumor, and CD3 expression on T cells do not show a notable difference among responders and non-responders.

Furthermore, we investigated the distributions of model components as potential predictive biomarkers including the density of different model cell types, and cytokine concentrations in the tumor and central compartment. To further explore these predictive biomarkers, we looked into different time points of the simulation, including pre-treatment (day 1), early on-treatment (here day 8, clinical trial taken at days 3–1717), and finally at the end of treatment (day 400). The nine most predictive biomarkers which are different among responders and non-responders are presented in Fig. 6. CD8+ T cell density in the tumor and central compartment, CD4+ T cells, helper T cells, and CD8+/Treg ratio in the tumor are higher in responders. We also looked into other predictive biomarkers like myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC), M1 and M2 macrophage density, which showed less significant differences among responders and non-responders (Supplementary Fig. 3). Regarding the cytokine concentrations, IFN-γ concentration was the most important one, having higher values in responders shown in Fig. 6, while the density of other cytokines like TGFβ, IL2, IL10, and IL12 were either less significant or showed no significance, Supplementary Fig. 4.

We further studied the potential biomarkers by ranking the biomarker candidates based on the highest response probability achieved among the VP subgroups generated for each biomarker candidate (see “Methods” section). Among the biomarker candidates tested, CD8+ density in tumor had the highest response probability of 0.43 (Fig. 7a). This was followed by the ratio of CD8+ T cells to the regulatory T cells, Treg, in the tumor compartment, which had a response probability of 0.36. Other biomarkers including CD3 expression on effector T cells, CD8+ T cell density in the central compartment, MDSC density in the tumor and Neo-Ag specific T cell clones had response probabilities between 0.15 and 0.2.

Top 15 single predictive biomarkers ranked based on response probability (a) and responder inclusion score (RIS) (b). c, d Comparison of response probability and RIS of the best single biomarker and biomarker combinations. e, f Distribution of response probability and RIS for all the biomarkers and their combinations tested. Response probability is calculated as the fraction of responders among VPs included in the subset. RIS is defined as the difference between the fraction of responders selected among responders in the entire patient cohort and the fraction of non-responders selected among non-responders in the whole cohort. Statistical significance is calculated using Wilcoxon test (ns/NS: p > 0.05; *: p ≤ 0.05; **: p ≤ 0.01; ****: p ≤ 0.0001). Box represents the interquartile range (IQR), line within the box indicates the median value of the data, whiskers extend to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 * IQR, outliers are the individual points that fall outside the whiskers. Patients with CR/PR were considered as responders. IFNg interferon-γ, Ag antigen, APC antigen-presenting cell, Th helper T cell.

To maximize the number of responders in the best subgroups selected (Supplementary Fig. 5), the responder inclusion score (RIS) metric was used (see “Methods” section). When biomarker candidates were ranked on the basis of the RIS, CD8+ density in the tumor showed the highest score, 0.55 (Fig. 7b). This was followed by the ratio of CD8+ T cell and Treg in the tumor compartment, CD8+ density in the central compartment and IL2 with a RIS above 0.26. Although biomarkers with high response probability do not necessarily have high RIS, the top two single biomarkers, CD8+ T cell density in the tumor and the ratio of CD8+ T cell to Treg density in the tumor were consistently the topmost for both metrics (Supplementary Fig. 6).

While the metric response probability is chosen to identify positive predictive biomarkers, i.e., biomarkers that select patients for treatment inclusion, biomarkers that inform exclusion criteria such as the negative predictive biomarkers are also clinically informative. To this end, we tested negative predictive biomarkers using the metric 1-response probability (Supplementary Fig. 7). Many biomarkers attained the highest score of 1, including biomarkers that were top-ranked for the selection of responders such as the ratio of CD8+ T cell to Treg density in the tumor. However, the predictive power of the identified biomarkers was low in excluding responders from the entire cohort, as <25% of non-responders from the entire cohort were correctly selected for treatment exclusion.

Combinations of pre-treatment predictive biomarkers

We evaluated whether combination of biomarkers achieve improved predictive power since the predictive ability of single biomarkers may be constrained. We tested combinations of biomarker candidates and generated subgroups of VPs on the basis of the levels of both biomarker candidates in the combination as described in “Methods” section. Among combinations of two biomarkers, the combination of naïve CD4+ T cell density in the central compartment with the ratio of CD8+ T cells to Treg in the tumor compartment had the highest response probability of 0.67. The best three and four biomarker combinations had response probability of 0.8 (Fig. 7c). The higher score achieved for biomarker combinations compared to single biomarker score of 0.43, shows a higher predictive power using biomarker combinations based on response probability analysis. Further, the distribution of response probability of the tested biomarker combinations showed a shift to the right compared to the distribution for single biomarkers (Fig. 7e). When two biomarker combinations were ranked on the basis of the RIS, the highest RIS attained was 0.57 for the combination of CD8+ T cell density in the tumor compartment and the ratio of CD8+ T cell and Tregs in the tumor compartment, suggesting only a small improvement in the predicitve power compared to the best single biomarker (Fig. 7d). No notable improvement in RIS was observed even for combinations of three or four biomarkers. Although the RIS of best single biomarker and best biomarker combinations were similar, there was a notable shift in the distribution of RIS to the right, for all combinations tested with two biomarkers compared to the distribution of single biomarkers (Fig. 7f). This observation suggests that there are several combinations that showed improved RIS compare to single biomarkers.

Analysis of potential predictive biomarkers

To further explore the effect of the biomarkers on model predictions, for the most significant biomarkers that were also common in both statistical analysis of responder and non-responders and biomarker ranking analysis, we sorted the VPs by each parameter in ascending order and evenly divided them into multiple subgroups. The ORR of each subgroup of therapy is plotted against the median parameter values in Fig. 8. As a result, predicted ORRs show a trend of increase with CD8+ density in the tumor and central compartment, CD4+, helper T cell densities, and CD8+/Treg ratio in the tumor, as well as APC and IFN-γ concentration, while ORRs decrease as naïve CD4+ density in central increases.

The virtual patient population was sorted by the pre-treatment variable level in ascending order for each variable and separated into five equal subgroups. Each subgroup in the combination therapy has its response status shown against the relevant median variable level. Blue represents partial or complete response (PR/CR). Green represents stable disease (SD). Red represents progressive disease (PD).

Predictive power of on-treatment biomarkers

In the final step, we evaluated on-treatment biomarkers, measured at early stages after treatment initiation, to test if they have higher predictive power compared to pre-treatment or baseline biomarkers. We calculated relative change in biomarker candidates at day 15 and day 30 after treatment initiation with respect to the baseline measurement. A large fraction of the tested biomarker candidates had an increase in response probability and RIS for relative change in biomarker candidates at day 15, compared to the predictive power at baseline (Fig. 9a, b). M1 macrophage density showed a >300% increase in response probability when relative change at day 15 was evaluated compared to baseline (Fig. 9a). Mature antigen-presenting cells showed a >1500% increase in RIS (Fig. 9b).

a, b Percentage change in response probability or RIS, for relative change in single biomarker quantities at day 15 after treatment initiation from baseline, calculated with respect to predictive power at baseline. Quantities shown in green and golden yellow, show an increase and decrease in predictive power with respect to baseline. c, d Comparison of response probabilities and RIS of the best single or composite biomarkers at different time points. Colors represent the time point of biomarker quantification (baseline, relative changes at day 15 or day 30 with respect to baseline). The numbers at the top of (c) and (d) indicate the number of biomarkers combined. Quantities that were assumed to be constant over time were excluded while calculating the relative change with respect to baseline. Statistical significance is calculated using Wilcoxon test (ns/NS: p > 0.05; ****: p ≤ 0.0001). Box represents the interquartile range (IQR), line within the box indicates the median value of the data, whiskers extend to the smallest and largest values within 1.5 * IQR, outliers are the individual points that fall outside the whiskers.

However, biomarkers such as CD8+ T cell density in central compartment and the ratio of CD8+ T cells to Tregs in tumor, had a decrease in predictive power, when relative change at early time point was considered compared to the baseline (Fig. 9a, b). Reduction in the predictive power of certain biomarkers after treatment initiation was also observed in biomarker analysis for PD-1 inhibition in breast cancer32, suggesting that this observation is not cancer-type or treatment specific. When the predictive power of best biomarkers was compared, relative change at day 15 or day 30 were higher compared to the pre-treatment biomarkers (Fig. 9c, d). Among all the tested single and composite biomarkers, the highest RIS attained was 0.82 with a combination of four biomarkers, including relative changes of M1/M2 macrophage ratio in the tumor, CD8+ T cell density in the tumor, ratio of CD8+ to Treg in the tumor and naïve CD8+ density in the central compartment, at day 15 with respect to the baseline. For a combination of relative changes in M2 macrophage density, CD8+/Treg ratio in the tumor and mature antigen-presenting cells, at day 15 from baseline, the maximum response probability of 1 was observed.

Discussion

Bispecific TCEs have grown to be a crucial component of cancer treatment research. However, improving the efficacy of bispecific TCE treatments in solid tumor treatment remains a significant challenge33,34. For instance, the clinical trials of tebentafusp showed great potential for the treatment of UM patients, yet the objective response rate remains modest21. Identifying the predictive biomarkers that can effectively distinguish responders from non-responders could improve the outcomes of clinical trials. To achieve this goal, mechanistic modeling approaches like QSP models are effective tools that can help predict and design trials to enhance efficacy35.

In this study, we extend our previously developed QSP platform for TCE29, to study predictive biomarkers for the treatment of UM patients with tebentafusp. To this end, we calibrated the model by fitting the model to available clinical and experimental data of UM and tebentafusp. In particular, the PK model was fitted to the published data of tebentafusp plasma concertation following the initial 20 mcg dose over a 1-week period20, other model parameters were fitted to available experimental data (Supplementary Data 2 and 3), and uncertain parameters were calibrated so the predicated ORR by simulation mimicking the ORR of phase 3 clinical trial21. We have also adopted the dynamics of T cells, helper T cells, APCs, tumor-specific neoantigens and tumor-associated self-antigens, immune checkpoints, and MDSCs from Wang et al.30.

Using this calibrated model, we investigated single predictive biomarkers as well as the combination of the selected biomarkers. CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells both play major roles in the UM tumor microenvironment, as evidenced by flow cytometry examination of 27 tumors, which revealed that a significant number of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes (TIL) were CD8+ T cells, with some CD4+ T cells36. Our findings showed that the density of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in the tumor compartment is substantially linked with response status, with a higher value in the responders’ group at all three time points of treatment investigated, Fig. 6. This is supported further by the mechanism of action of tebentafusp, which has been demonstrated to activate and redirect both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells to lyse gp100+ cancer cells19. Moreover, Foxp3+ Treg were found to be present in 12–24% of UMs37,38 and our work demonstrated that the pre-treatment CD8+/Treg cell ratio can serve as an important predictive biomarker, with higher values of this ratio for responders, Fig. 6. Furthermore, statistical analysis of responders and non-responders revealed that the average Treg density in the tumor compartment is higher for responders, whereas the Treg density in the central compartment is lower for the responder group, Supplementary Fig. 3.

It is noteworthy to highlight that the assessment report of tebentafusp revealed a decrease in lymphocyte count within 24 h following the initial dose, with a return to baseline levels by day 839. While our analysis does not specifically address the lymphocyte density at the 24-h mark, the simulated values of early treatment at day 8 for CD8+ T cells, T helper, and Tregs in the central (blood) compartment exhibit a very similar distribution to baseline values on day 1, as shown in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 3.

Not only T cells but also tumor-associated macrophages are commonly present in UM with the majority of them being M2 type, and in the study of UM patients without treatment survival was much better in patients with low M2 macrophages40. However, the statistical analysis revealed somewhat higher M2 macrophage levels in responders at the start of treatment, and a significant rise in M2 macrophage levels after treatment with tebentafusp. This observation has been also reported by clinical/experimental studies for other treatments. Local treatment of UM tumors with thermotherapy, for example, promoted the influx of macrophages41, and following transscleral thermotherapy, a high density of M2 macrophages was identified along the boundaries of treated regions42.

Cytokines also play an essential role in the tumor microenvironment of UM as was demonstrated by a high concentration of various cytokines and chemokines in a study of UM patients43. In this work, we looked at the differences between responders and non-responders based on the cytokines used in the model, which included IFN-γ, TGFb, IL2, IL10, and IL12. Among these cytokines, IFN-γ was chosen as the most significant biomarker. Although IFN-γ can have both anti-tumor and pro-tumor functions44, our study results suggest a higher value of this cytokine in the responder group with tebentafusp therapy.

Another powerful predictive biomarker is tumor purity, which is defined as the ratio of cancer cells to all species in the tumor compartment (e.g., T cells, macrophages, MDSC). Although tumor purity is lower at all treatment time points for responders, the values after treatment are notably different for the two groups, reflecting cancer lysis for the responders’ group at the end of therapy.

Although the selected range of expression levels for biomarkers such as CD47 and gp100 on tumor cells and CD3 on T cells did not show a significant difference between responders and non-responders and they were among the middle-ranked biomarkers, their expression may be important for further analysis with a wider range of expression level and also their interaction with other cell types in the tumor microenvironment. For example, the study of immune cell populations in UM patients showed a significantly higher number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells can be found in patients with high CD47 levels45. Furthermore, we assumed in our simulations that biomarker expression levels are constant and do not vary during treatment. While it has been demonstrated that tebentafusp does not change gp100 expression levels17, the drug’s effect on the expression levels of other biomarkers is not well understood.

One of the limitation of our model is its focus on Tregs and PD-1/PD-L1 signaling as the primary causes of T cell exhaustion. Our model does not incorporate the effects of prolonged exposure to inflammatory cytokines or continuous antigen exposure which both are contributors to T cell exhaustion. Future incorporation of these factors to the model would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms driving T cell exhaustion and to enhance the model’s predictive accuracy.

Quantification of predictive power also revealed combinations of pre-treatment and on-treatment biomarkers with high predictive power. Future work examining clusters of correlated predictive biomarkers will provide mechanistic insights and would enable a rational development of strategies to accurately predict treatment responses. The metrics used to evaluate biomarkers, response probability and RIS could be interpreted in terms of specificity and sensitivity32. Biomarkers with high response probability have high specificity, which is defined as the ability of biomarkers to exclude non-responders or minimize false positives, and are useful only for a specific population of patients. On the other hand, biomarkers with high RIS have high specificity and sensitivity, where sensitivity is the ability of biomarkers to minimize false negatives. Thus, biomarkers identified based on RIS are widely applicable and are preferable. However, while none of the biomarkers and their combinations tested achieved a RIS of 1 suggesting that the tested biomarkers had a specificity or sensitivity less than 100%, a combination of on-treatment M2 macrophage density, CD8+/Treg ratio in the tumor and mature antigen-presenting cells had 100% specificity or response probability of 1. Thus, biomarkers will have to be selected depending on the required tradeoff between sensitivity and sensitivity.

It should be noted that we consider ratios of two quantities such as the ratio of CD8+ T cell and Treg density as a single derived biomarker quantity. For single biomarker analysis in this work, a single cutoff for the (derived) quantity is used to select VPs. In the case of biomarker combination analysis, multiple cutoffs (each for a biomarker quantity in combination) are used in the selection of VPs. However, in a strict sense, the ratios of two quantities could be considered as biomarker combination and the predictive power would vary depending on the way the two quantities are combined. Future studies comparing different strategies to combine biomarker quantities are required to establish a standard method for testing biomarker combinations.

In summary, the objective of this study is to establish a patient selection process driven by biomarkers, using a QSP modeling methodology. Nevertheless, accurately estimating parameters and generating VPs remain a significant challenge in QSP models. Looking forward, we anticipate that as more data become accessible, these models will enhance their capacity to predict outcomes with higher precision46,47.

Methods

Model structure

The QSP model used in this study was based on our previous models developed for triple-negative breast cancer and TCE, and detailed governing equations have been formulated and explained in detail29,30. The model comprises four compartments representing different aspects of the patient: central (blood), peripheral (other tissues and organs), tumor, and TDLN, Fig. 1. This entire model is formulated using a combination of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) and algebraic equations. The model includes specific modules for cancer cells, T cells, antigen presentation, MDSC, macrophages, and TCE antibody PK.

The behavior and interactions of crucial cellular and molecular species, including T cells, cancer cells, antigen-presenting cells, antigens, checkpoint ligands and receptors, and antibodies, are represented by each module in this complete model. This level of cellular and molecular specificity makes it simple to incorporate new modules that can describe different species and therapeutic agents.

The model consists of a total of 154 ODEs, 42 algebraic equations, and 285 parameters. To ensure the paper’s comprehensiveness and self-sufficiency, we have provided the computational code for the entire model. Moreover, all the equations with descriptions of reactions and rules governing tumor growth, antigen processing and presentation, T cell activation, proliferation, and distribution, MDSC recruitment into tumor, macrophage dynamics, and drug PK/PD are provided in Supplementary Data 5 and 6.

In this study, we focused on tebentafusp, distributed under the brand name Kimmtrak®, which is bivalent for the target antigen (gp100) on cancer cells and monovalent for CD3 on T cells. PK parameters were fitted to the data reported and the simulated plasma concentration of tebentafusp together with the clinical measurements at dose levels of 20 mcg QW in the central compartment (Supplementary Note and Supplementary Fig. 1a). In our model, we considered the CD3 expression on both Teff and Treg cells, and equations used for the binding model can be found in Supplementary Data 5.

Model initiation and virtual clinical trial

In order to simulate a VP group mirroring the real clinical population, values of a selected subset of model parameters are randomly generated via LHS, while others are held at their baseline values. These baseline values and the parameter distributions are informed by existing experimental and clinical data. For instance, the pre-treatment size of UM tumor in 8033 patients was reported by Shields et al.48. The tumor growth rate was estimated using the calculated doubling times of UM tumors reported by Char et al.49. The range of TMB which is represented by the number of neoantigen (Neo-Ag)-specific T cell clones, was fitted to the data of the reported genetic landscape of UM40. Moreover, we have used available experimental data for UM to select the range of expression levels of different proteins like PDL1, PDL2, CD4750, and gp100 on cancer cells51, CD3 on T cells52, and the ratio of M2/M1 macrophages53. For the full list of parameters and selected ranges, see Supplementary Data 2 and 3.

It is important to emphasize that there are certain parameters for which the distributions are unavailable. For these parameters, we have approximated their ranges in a way that ensures the simulated ORR’s 95% CI aligns with the clinical trial outcomes (the percentage of partial or complete response (PR/CR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD)) as per RECIST criteria.

The model is simulated by representing each randomly generated set of parameters as a VP. Then, the simulations are conducted within the MATLAB SimBiology Toolbox (MathWorks, Natick, MA) using the SUNDIALS solver. For every VP, a pre-treatment tumor size was randomly assigned, and the simulation began with a small number of cancer cells and continued until the tumor attained the desired size. VPs unable to achieve this desired pre-treatment tumor size are excluded from the treatment simulation. Upon reaching the desired pre-treatment size, the drug administration is simulated through a SimBiology dose object. This object defines parameters like dosage, infusion duration, and dosing schedule. Subsequently, the tumor dynamic is simulated for 400 days. During the post-processing phase, additional filtration is applied to the VPs to ensure that their attributes (e.g., range of reported T cells densities, and Teff/Treg ratio) remain within biologically plausible ranges.

Statistical analysis

In order to investigate the effects of different parameters on model data, global uncertainty and sensitivity analyses are carried out using LHS and PRCC approaches54. The 95 percentile bootstrap CIs are produced for comparison between model predictions and clinical results, and the overall response rate (ORR) and duration of response are projected based on RECIST V.1.155. Based on the normal approximation for the binomial distribution, 95% Agresti–Coull CIs are computed for the ORR predictions in subgroup analysis. Additionally, three algorithms of MRMR, F-test, and RReliefF which are included in the feature selection section of the Regression Learner App of MATLAB56 were used to quantify the importance of each parameter on tumor volume in the context of machine learning. Finally, to compare model observations in subgroups with various response statuses and treatment regimens, the Wilcoxon test is performed using the ggpubr package in RStudio V.1.257.

Biomarker ranking

To quantify and rank the biomarker candidates, the cutoff-based biomarker testing algorithm described in ref. 32 was used. This method is a modified version of the algorithm introduced in ref. 58 with improved computational speed and robustness, and it enables testing single and combination of predictive biomarkers. The 910 VPs generated were randomly split into train and test sets comprising 637 (70%) and 273 (30%) VPs, respectively. First, optimal cutoffs for single biomarkers were identified using the train dataset as follows. For every biomarker candidate, eight quantiles were chosen as potential cutoffs and VPs with the corresponding biomarker level above/below the cutoff points were generated. VP subsets with <20 patients were excluded from the analysis to avoid artifacts due to the low number of patients. Two metrics were used separately to rank the biomarker candidates (1) response probability and (2) RIS. Response probability is calculated as the fraction of responders among VPs included in the subset. RIS is defined as the difference between the fraction of responders selected among responders in the entire patient cohort and the fraction of non-responders selected among non-responders in the whole cohort. Thus, RIS maximizes the selection of responders from the whole patient cohort but response probability only maximizes the fraction of responders within the subset of selected patients. For each biomarker, the optimal cutoff values that maximized response probability and RIS were separately identified. The predictive power of biomarkers based on the two metrics were evaluated with the test dataset, using the optimal cutoff identified. Biomarker candidates were then ranked based on the highest value of response probability/RIS attained among the VP subsets generated using the test dataset. To analyze biomarker combinations, a random forest-based feature selection was applied to prefilter biomarker candidates using the train data. Subsequently, all possible combinations (combinations of two, three, and four biomarkers) of selected biomarker candidates and their cutoffs were chosen to identify the optimal set of cutoffs for biomarkers in combination. For each set of cutoffs, VP subsets were generated that satisfy the cutoff criteria of all biomarkers in the combination, using the train dataset. This also includes scenarios where one biomarker is above the cutoff while the other biomarker is below the cutoff. Predictive power of optimal cutoffs identified for biomarkers in combination was evaluated using the test dataset. A flow chart of the biomarker testing algorithm is provided in the Supplementary text of ref. 32.

In this analysis, responders refer to patients with CR/PR and non-responders include patients with SD and PD. This analysis was performed separately for pre-treatment or baseline biomarkers and on-treatment biomarkers such as relative changes in biomarker candidates at day 15 or day 30 after treatment initiation with respect to the baseline.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and the Supplementary Material.

Code availability

The model code and MATLAB script used in this study are available at Anbari, Samira (2024), “Identifying biomarkers for treatment of uveal melanoma by T cell engager using a QSP model. Mendeley Data, V1. https://doi.org/10.17632/vfj4wrkkfs.1.

References

Chang, A. E., Karnell, L. H. & Menck, H. R. The National Cancer Data base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: a summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. Cancer 83, 1664–1678 (1998).

McLaughlin, C. C. et al. Incidence of noncutaneous melanomas in the U.S. Cancer 103, 1000–1007 (2005).

Chattopahdyay, C. et al. Uveal melanoma: from diagnosis to treatment and the science in between. Aust. Art F. Pract. Policies Inst. 122, 2299–2312 (2016).

Seedor, R. S. et al. An outcome assessment of a single institution’s longitudinal experience with uveal melanoma patients with liver metastasis. Cancers 12, 1–14 (2020).

Diener-West, M. et al. Screening for metastasis from choroidal melanoma: the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Report 23. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 2438–2444 (2004).

Rodriguez-Vidal, C. et al. Treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma: systematic review. Cancers 12, 1–22 (2020).

Wessely, A. et al. The role of immune checkpoint blockade in uveal melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 879 (2020).

Piulats Rodriguez, J. M. et al. Phase II study evaluating ipilimumab as a single agent in the first-line treatment of adult patients (Pts) with metastatic uveal melanoma (MUM): the GEM-1 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 9033 (2014).

Zimmer, L. et al. Phase II DeCOG-study of ipilimumab in pretreated and treatment-naïve patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. PLoS ONE 10, 1–13 (2015).

Algazi, A. P. et al. Clinical outcomes in metastatic uveal melanoma treated with PD-1 and PD-L1 antibodies. Cancer 122, 3344–3353 (2016).

Weis, E., Shah, C. P., Lajous, M., Shields, J. A. & Shields, C. L. The association of cutaneous and iris nevi with uveal melanoma: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 116, 536–543.e2 (2009).

Johansson, P. et al. Deep sequencing of uveal melanoma identifies a recurrent mutation in PLCB4. Oncotarget 7, 4624–4631 (2016).

Bakhoum, M. F. & Esmaeli, B. Molecular characteristics of uveal melanoma: insights from the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) project. Cancers 11, 1061 (2019).

Yarchoan, M., Hopkins, A. & Jaffee, E. M. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 2500–2501 (2017).

Javed, A. et al. PD-L1 expression in tumor metastasis is different between uveal melanoma and cutaneous melanoma. Immunotherapy 9, 1323–1330 (2017).

Orloff, M., Seedor, R. & Sato, T. Review of bi-specific therapies in uveal melanoma. Cancer Gene Ther. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41417-022-00442-9 (2022).

Middleton, M. R. et al. Tebentafusp, a TCR/Anti-CD3 bispecific fusion protein targeting gp100, potently activated antitumor immune responses in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 5869–5878 (2020).

Martinez-Perez, D., Viñal, D., Solares, I., Espinosa, E. & Feliu, J. Gp-100 as a novel therapeutic target in uveal melanoma. Cancers 13, 1–9 (2021).

Boudousquie, C. et al. Polyfunctional response by ImmTAC (IMCgp100) redirected CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Immunology 152, 425–438 (2017).

Carvajal, R. D. et al. Phase I study of safety, tolerability, and efficacy of tebentafusp using a step-up dosing regimen and expansion in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 1939–1948 (2022).

Nathan, P. et al. Overall survival benefit with tebentafusp in metastatic uveal melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1196–1206 (2021).

Betts, A. & van der Graaf, P. H. Mechanistic quantitative pharmacology strategies for the early clinical development of bispecific antibodies in oncology. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 108, 528–541 (2020).

Betts, A. et al. A translational quantitative systems pharmacology model for CD3 bispecific molecules: application to quantify T cell-mediated tumor cell killing by P-cadherin LP DART®. AAPS J. 21, 66 (2019).

van de Vyver, A. J. et al. Predicting tumor killing and t-cell activation by t-cell bispecific antibodies as a function of target expression: combining in vitro experiments with systems modeling. Mol. Cancer Ther. 20, 357–366 (2021).

Hosseini, I. et al. Mitigating the risk of cytokine release syndrome in a Phase I trial of CD20/CD3 bispecific antibody mosunetuzumab in NHL: impact of translational system modeling. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 6, 28 (2020).

Weddell, J. Mechanistically modeling peripheral cytokine dynamics following bispecific dosing in solid tumors. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 1–12 https://doi.org/10.1002/psp4.12928 (2023).

Ma, H. et al. A quantitative systems pharmacology model of T cell engager applied to solid tumor. AAPS J. 22, 1–16 (2020).

Ma, H. et al. Combination therapy with T cell engager and PD-L1 blockade enhances the antitumor potency of T cells as predicted by a QSP model. J. Immunother. Cancer 8, 1–11 (2020).

Anbari, S. et al. Using quantitative systems pharmacology modeling to optimize combination therapy of anti-PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor and T cell engager. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1–10 (2023).

Wang, H., Zhao, C., Santa-Maria, C. A., Emens, L. A. & Popel, A. S. Dynamics of tumor-associated macrophages in a quantitative systems pharmacology model of immunotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer. iScience 25, 104702 (2022).

Aran, D., Sirota, M. & Butte, A. J. Systematic pan-cancer analysis of tumour purity. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–12 (2015).

Arulraj, T. et al. Virtual patient analysis identifies strategies to improve the performance of predictive biomarkers for PD-1 blockade. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.21.595235 (2024).

Dahlén, E., Veitonmäki, N. & Norlén, P. Bispecific antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. Ther. Adv. Vaccines Immunother. 6, 3–17 (2018).

Zhou, S., Liu, M., Ren, F., Meng, X. & Yu, J. The landscape of bispecific T cell engager in cancer treatment. Biomark. Res. 9, 1–23 (2021).

Morcos, P. N., Li, J., Hosseini, I. & Li, C. C. Quantitative clinical pharmacology of T-cell engaging bispecifics: current perspectives and opportunities. Clin. Transl. Sci. 75–85 https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12877 (2020).

Char, D. H., Char, D. H. & Kaleta-Michaels, S. Infiltrating lymphocytes and antigen expression in uveal melanoma. Ophthalmic Res. 24, 20–26 (1992).

Lagouros, E. et al. Infiltrative T regulatory cells in enucleated uveal melanomas. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 107, 223–228 (2009).

Mougiakakos, D. et al. Intratumoral forkhead box p3-positive regulatory t cells predict poor survival in cyclooxygenase-2-positive uveal melanoma. Cancer 116, 2224–2233 (2010).

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Assessment report (EPAR)—Saphnelo. 31 (EMA, 2022).

Royer-Bertrand, B. et al. Comprehensive genetic landscape of uveal melanoma by whole-genome sequencing. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 1190–1198 (2016).

Schurmans, L. R. H. M. et al. Effects of transpupillary thermotherapy on immunological parameters and apoptosis in a case of primary uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 9, 297–302 (1999).

Dennaoui, J. et al. Changes in immunological markers and influx of macrophages following trans-scleral thermotherapy of uveal melanoma. Acta Ophthalmol. 89, 268–273 (2011).

Nagarkatti-Gude, N., Bronkhorst, I. H. G., van Duinen, S. G., Luyten, G. P. M. & Jager, M. J. Cytokines and chemokines in the vitreous fluid of eyes with uveal melanoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53, 6748–6755 (2012).

Zaidi, M. R. The interferon-gamma paradox in cancer. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 39, 30–38 (2019).

Petralia, M. C. et al. Characterization of the pathophysiological role of CD47 in uveal melanoma. Molecules 24, 2450 (2019).

Azer, K. et al. History and future perspectives on the discipline of quantitative systems pharmacology modeling and its applications. Front. Physiol. 12, 637999 (2021).

Cheng, L., Qiu, Y., Schmidt, B. J. & Wei, G. W. Review of applications and challenges of quantitative systems pharmacology modeling and machine learning for heart failure. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 49, 39–50 (2022).

Shields, C. L. et al. Metastasis of uveal melanoma millimeter-by-millimeter in 8033 consecutive eyes. Arch. Ophthalmol. 127, 989–998 (2009).

Char, D. H., Kroll, S. & Phillips, T. L. Uveal melanoma growth rate and prognosis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 115, 1014–1018 (1997).

Basile, M. S. et al. Differential modulation and prognostic values of immune-escape genes in uveal melanoma. PLoS ONE 14, 1–16 (2019).

Lepage, S. & Lapointe, R. Melanosomal targeting sequences from gp100 are essential for MHC class II-restricted endogenous epitope presentation and mobilization to endosomal compartments. Cancer Res. 66, 2423–2432 (2006).

Nicolas, L. et al. Human γδ T cells express a higher TCR/CD3 complex density than αβ T cells. Clin. Immunol. 98, 358–363 (2001).

Matsuo, H., Kamatani, T., Hamba, Y., Boroevich, K. A. & Tsunoda, T. Association between high immune activity and worse prognosis in uveal melanoma and low-grade glioma in TCGA transcriptomic data. BMC Genomics 23, 1–10 (2022).

Marino, S., Hogue, I. B., Ray, C. J. & Kirschner, D. E. A methodology for performing global uncertainty and sensitivity analysis in systems biology. J. Theor. Biol. 254, 178–196 (2008).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009).

Regression Learner App. https://www.mathworks.com/help/stats/regression-learner-app.html.

Kassambara, A. ggpubr: ‘ggplot2’ based publication ready plots. R package version 0.2.2. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggpubr (2019).

Arulraj, T., Wang, H., Emens, L. A., Santa-Maria, C. A. & Popel, A. S. A transcriptome-informed QSP model of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer identifies predictive biomarkers for PD-1 inhibition. Sci. Adv. 9, 1–18 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and in part by NIH Grant R01CA138264 (A.S.P.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A., S.H., and A.S.P. designed the project; A.S.P., S.H. and J.W. directed the project; S.A. and H.W. built and modified the model; S.A., H.W. and T.A. contributed analysis tools; S.A. performed all simulations, collected the data and drafted the manuscript; S.A., H.W., T.A., M.N., J.W., M.P., S.H., and A.S.P. revised the manuscript critically; all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.P., M.N., J.W., and S.H. are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. A.S.P. is a consultant to J&J/Janssen, Incyte, and AsclepiX Therapeutics. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Anbari, S., Wang, H., Arulraj, T. et al. Identifying biomarkers for treatment of uveal melanoma by T cell engager using a QSP model. npj Syst Biol Appl 10, 108 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-024-00434-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-024-00434-5

This article is cited by

-

Quantitative systems pharmacology models: unleashing their potential in cancer immunotherapy

Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation (2026)

-

Quantitative cancer-immunity cycle modeling for predicting disease progression in advanced metastatic colorectal cancer

npj Systems Biology and Applications (2025)

-

QSP modeling of loncastuximab tesirine with T-cell-dependent bispecific antibodies guides dose-regimen strategy

npj Systems Biology and Applications (2025)