Abstract

Neurobiological and psychological models of learning emphasize the importance of prediction errors (surprises) for memory formation. This relationship has been shown for individual momentary surprising events; however, it is less clear whether surprise that unfolds across multiple events and timescales is also linked with better memory of those events. We asked basketball fans about their most positive and negative autobiographical memories of individual plays, games and seasons, allowing surprise measurements spanning seconds, hours and months. We used advanced analytics on National Basketball Association play-by-play data and betting odds spanning 17 seasons, more than 22,000 games and more than 5.6 million plays to compute and align the estimated surprise value of each memory. We found that surprising events were associated with better recall of positive memories on the scale of seconds and months and negative memories across all three timescales. Game and season memories could not be explained by surprise at shorter timescales, suggesting that long-term, multi-event surprise correlates with memory. These results expand notions of surprise in models of learning and reinforce its relevance in real-world domains.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All relevant data necessary to reproduce these results are available at https://github.com/JamesWardAntony/bball_am. Other databases include the following: NBA API for play-by-play data (https://github.com/swar/nba_api); expert website with play-by-play win probabilities (https://www.inpredictable.com); year-by-year data on points scored versus points scored against for each team (for calculating team strength) (https://www.basketball-reference.com). Note that data we obtained on game-by-game betting odds are no longer available from the source that we obtained them from, but many of them can be found at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ehallmar/nba-historical-stats-and-betting-data and all the ones used in our dataset are in our data repository.

Code availability

All relevant code necessary to reproduce these results as Google Colab notebooks are available at https://github.com/JamesWardAntony/bball_am.

References

Rouhani, N., Norman, K. & Niv, Y. Dissociable effects of surprising rewards on learning and memory. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 44, 1430 (2018).

Rouhani, N., Norman, K. A., Niv, Y. & Bornstein, A. M. Reward prediction errors create event boundaries in memory. Cognition 203, 104269 (2020).

Jang, A. I., Nassar, M. R., Dillon, D. G. & Frank, M. J. Positive reward prediction errors during decision-making strengthen memory encoding. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 719–732 (2019).

Huang, J., Velarde, I., Ma, W. J. & Baldassano, C. Schema-based predictive eye movements support sequential memory encoding. eLife 12, e82599 (2023).

Rescorla, R. A. & Wagner, A. R. in Classical Conditioning II: Current Research and Theory (eds Black, A. H. & Prokasy, W. F.) 64–99 (Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1972).

Metcalfe, J. Learning from errors. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 68, 465–489 (2017).

Antony, J. W. et al. Behavioral, physiological, and neural signatures of surprise during naturalistic sports viewing. Neuron 109, 377–390 (2021).

Brod, G. Predicting as a learning strategy. Psychonom. Bull. Rev. 28, 1839–1847 (2021).

Kapur, N. Syndromes of retrograde amnesia: a conceptual and empirical synthesis. Psychol. Bull. 125, 800–825 (1999).

Lisman, J. E. & Grace, A. A. The hippocampal-VTA loop: controlling the entry of information into long-term memory. Neuron 46, 703–713 (2005).

Greve, A., Cooper, E., Kaula, A., Anderson, M. C. & Henson, R. Does prediction error drive one-shot declarative learning? J. Mem. Lang. 94, 149–165 (2017).

Pine, A., Sadeh, N., Ben-Yakov, A., Dudai, Y. & Mendelsohn, A. Knowledge acquisition is governed by striatal prediction errors. Nat. Commun. 9, 1673 (2018).

Kafkas, A. & Montaldi, D. Striatal and midbrain connectivity with the hippocampus selectively boosts memory for contextual novelty. Hippocampus 25, 1262–1273 (2015).

Takahashi, Y. K. et al. Dopamine neurons respond to errors in the prediction of sensory features of expected rewards. Neuron 95, 1395–1405.e3 (2017).

Howard, J. D. & Kahnt, T. Identity prediction errors in the human midbrain update reward-identity expectations in the orbitofrontal cortex. Nat. Commun. 9, 1611 (2018).

Frank, D., Kafkas, A. & Montaldi, D. Experiencing surprise: the temporal dynamics of its impact on memory. J. Neurosci. 42, 6435–6444 (2022).

Murty, V. P., LaBar, K. S. & Adcock, R. A. Distinct medial temporal networks encode surprise during motivation by reward versus punishment. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 134, 55–64 (2016).

Duncan, K., Ketz, N., Inati, S. J. & Davachi, L. Evidence for area CA1 as a match/mismatch detector: a high-resolution fMRI study of the human hippocampus. Hippocampus 22, 389–398 (2012).

Bein, O., Duncan, K. & Davachi, L. Mnemonic prediction errors bias hippocampal states. Nat. Commun. 11, 3451 (2020).

Garrido, M. I., Barnes, G. R., Kumaran, D., Maguire, E. A. & Dolan, R. J. Ventromedial prefrontal cortex drives hippocampal theta oscillations induced by mismatch computations. NeuroImage 120, 362–370 (2015).

Long, N. M., Lee, H. & Kuhl, B. A. Hippocampal mismatch signals are modulated by the strength of neural predictions and their similarity to outcomes. J. Neurosci. 36, 12677–12687 (2016).

Gruber, M. J. et al. Theta phase synchronization between the human hippocampus and prefrontal cortex increases during encoding of unexpected information: a case study. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 30, 1646–1656 (2017).

Frank, D., Montemurro, M. A. & Montaldi, D. Pattern separation underpins expectation-modulated memory. J. Neurosci. 40, 3455–3464 (2020).

Sinclair, A. H., Manalili, G. M., Brunec, I. K., Adcock, R. A. & Barense, M. D. Prediction errors disrupt hippocampal representations and update episodic memories. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2117625118 (2021).

Preuschoff, K., ’t Hart, B. M. & Einhauser, W. Pupil dilation signals surprise: evidence for noradrenaline’s role in decision making. Front. Neurosci. 5, 115 (2011).

Braem, S., Coenen, E., Bombeke, K., van Bochove, M. E. & Notebaert, W. Open your eyes for prediction errors. Cogn., Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 15, 374–380 (2015).

Filipowicz, A. L. S., Glaze, C. M., Kable, J. W. & Gold, J. I. Pupil diameter encodes the idiosyncratic, cognitive complexity of belief updating. eLife 9, e57872 (2020).

Clewett, D., Gasser, C. & Davachi, L. Dynamic arousal signals construct memories of time and events. Nat. Commun. 11, 4007 (2020).

Theobald, M. et al. Predicting vs guessing: the role of confidence for pupillometric markers of curiosity and surprise. Cogn. Emot. 36, 731–740 (2022).

Ostwald, D. et al. Evidence for neural encoding of Bayesian surprise in human somatosensation. NeuroImage 62, 177–188 (2012).

Reichardt, R., Polner, B. & Simor, P. Novelty manipulations, memory performance, and predictive coding: the role of unexpectedness. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 1–11 (2020).

Pearce, J. M. & Hall, G. A model for Pavlovian learning: variations in the effectiveness of conditioned but not of unconditioned stimuli. Psychol. Rev. 87, 532–552 (1980).

Redgrave, P., Prescott, T. J., Gurney, K., Redgrave, P. & Prescott, T. J. Is the shortlatency dopamine response too short to signal reward error? Trends Neurosci. 2236, 146–151 (1999).

Corbetta, M. & Shulman, G. L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 201–215 (2002).

Ranganath, C. & Rainer, G. Neural mechanisms for detecting and remembering novel events. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 193–202 (2003).

Bradley, M. M. Natural selective attention: orienting and emotion. Psychophysiology 46, 1–11 (2009).

Sukalla, F., Shoenberger, H. & Bolls, P. D. Surprise! An investigation of orienting responses to test assumptions of narrative processing. Commun. Res. 43, 844–862 (2016).

Demeter, E., Glassberg, B., Gamble, M. L. & Woldorff, M. G. Reward magnitude enhances early attentional processing of auditory stimuli. Cogn., Affect., Behav. Neurosci. 22, 268–280 (2022).

Itti, L. & Baldi, P. Bayesian surprise attracts human attention. Vis. Res. 49, 1295–1306 (2009).

Rouhani, N. & Niv, Y. Signed and unsigned reward prediction errors dynamically enhance learning and memory. eLife 10, e61077 (2021).

Niv, Y. & Schoenbaum, G. Dialogues on prediction errors. TICS 12, 265–272 (2008).

Mackintosh, N. J. A theory of attention: variations in the associability of stimuli with reinforcement. Psychol. Rev. 82, 276–298 (1975).

Schultz, W., Dayan, P. & Montague, P. R. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 275, 1593–1599 (1997).

D’Ardenne, K., McClure, S. M., Nystrom, L. E. & Cohen, J. D. BOLD responses reflecting dopaminergic signals in the human ventral tegmental area. Science 319, 1264–1267 (2008).

Bayer, H. M. & Glimcher, P. W. Midbrain dopamine neurons encode a quantitative reward prediction error signal. Neuron 47, 129–141 (2005).

Calderon, C. B. et al. Signed reward prediction errors in the ventral striatum drive episodic memory. J. Neurosci. 41, 1716–1726 (2021).

De Loof, E., Naert, L., Van Opstal, F. & Verguts, T. Signed reward prediction errors drive episodic learning. PLoS ONE 13, e0189212 (2018).

Momennejad, I. & Howard, M. W. Predicting the future with multi-scale successor representations. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/449470 (2018).

Wimmer, G. E. & Buchel, C. Learning of distant state predictions by the orbitofrontal cortex in humans. Nat. Commun. 10, 2554 (2019).

Tiganj, Z., Tang, W. & Howard, M. W. A computational model for simulating the future using a memory timeline. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 43, 1173–1179 (2021).

Rabovsky, M., Hansen, S. S. & Mcclelland, J. L. Modelling the N400 brain potential as change in a probabilistic representation of meaning. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 693–705 (2018).

Goldstein, A. et al. Shared computational principles for language processing in humans and deep language models. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 369–380 (2022).

Kumar, M. et al. Bayesian surprise predicts human event segmentation in story listening. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/qd2ra (2022).

Nieuwland, M. S. & Van Berkum, J. J. A. When peanuts fall in love: N400 evidence for the power of discourse. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 18, 1098–1111 (2006).

Chien, H. S. & Honey, C. J. Constructing and forgetting temporal context in the human cerebral cortex. Neuron 106, 675–686 (2020).

Weinstein, N. D. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 39, 806–820 (1980).

Ersner-Hershfield, H., Wimmer, G. E. & Knutson, B. Saving for the future self: Neural measures of future self-continuity predict temporal discounting. SCAN 4, 85–92 (2009).

Brietzke, S. & Meyer, M. L. Temporal self-compression: behavioral and neural evidence that past and future selves are compressed as they move away from the present. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2101403118 (2021).

Loewenstein, G. & D. Schkade, D. in Well-Being: Foundations of Hedonic Psychology (eds Kahneman, D. et al.) 85–105 (Russell Sage Foundation, 1997).

Granberg, D. & Brent, E. When prophecy bends: the preference-expectation link in U.S. presidential elections, 1952-1980. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 45, 477–491 (1983).

Babad, E. & Katz, Y. Wishful thinking–against all odds. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 21, 1921–1938 (1991).

Ferguson, P. J. & Lakhani, K. R. Consuming contests: Outcome uncertainty and spectator demand for contest-based entertainment. Unit Working Paper No. 21-087. Working Knowledge https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/consuming-contests-outcome-uncertainty-and-spectator-demand (2021).

Whitney, J. D. Winning games versus winning championships: the economics of fan interest and team performance. Econom. Inq. XXVI, 703–724 (1988).

Congleton, A. R. & Berntsen, D. How suspense and surprise enhance subsequent memory: the case of the 2016 United States Presidential Election. Memory 30, 317–329 (2022).

Chiew, K. S., Harris, B. B. & Adcock, R. A. Remembering election night 2016: subjective but not objective metrics of autobiographical memory vary with political affiliation, affective valence, and surprise. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 151, 390–409 (2021).

Terner, Z. & Franks, A. Modeling player and team performance in basketball. Ann. Rev. Stat. Appl. 8, 1–23 (2021).

Branscombe, N. R. & Wann, D. L. The positive social and self concept consequences of sports team identification. J. Sport Soc. Issues 15, 115–127 (1991).

Wann, L. & Branscombe, R. Die-hard and fair-weather fans: effects of identification on BIRGing and CORFing tendencies. J. Sport Soc. Issues 14, 103–117 (1990).

Kensinger, E. A. When the Red Sox shocked the Yankees: comparing negative and positive memories. Psychonom. Bull. Rev. 13, 757–763 (2006).

Kensinger, E. A. & Corkin, S. Memory enhancement for emotional words: are emotional words more vividly remembered than neutral words? Mem. Cogn. 31, 1169–1180 (2003).

Wang, J., Tambini, A. & Lapate, R. C. The tie that binds: temporal coding and adaptive emotion. Trends Cogn. Sci. 26, 1103–1118 (2022).

Brown, R. & Kulik, J. Flashbulb memories. Cognition 5, 73–99 (1977).

Cooper, R. A., Kensinger, E. A. & Ritchey, M. Memories fade: the relationship between memory vividness and remembered visual salience. Psychological Sci. 30, 657–668 (2019).

Dolcos, F., Labar, K. S. & Cabeza, R. Remembering one year later: role of the amygdala and the medial temporal lobe memory system in retrieving emotional memories. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2626–2631 (2005).

Williams, S. E., Ford, J. H. & Kensinger, E. A. The power of negative and positive episodic memories. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 22, 869–903 (2022).

Sharot, T., Delgado, M. R. & Phelps, E. A. How emotion enhances the feeling of remembering. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 1376–1380 (2004).

Maguire, E. A. & Mummery, C. J. Differential modulation of a common memory retrieval network revealed by positron emission tomography. Hippocampus 9, 54–61 (1999).

Yonelinas, A. P. & Ritchey, M. The slow forgetting of emotional episodic memories: an emotional binding account. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19, 259–267 (2015).

Pillemer, D. B. Flashbulb memories of the assassination attempt on President Reagan. Cognition 16, 63–80 (1984).

Bohannon, J. N. Flashbulb memories for the space shuttle disaster: a tale of two theories. Cognition 29, 179–196 (1988).

Wright, D. B. Recall of the Hillsborough disaster over time: systematic biases of ‘flashbulb’ memories. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 7, 129–138 (1993).

Hirst, W. et al. Long-term memory for the terrorist attack of September 11: flashbulb memories, event memories, and the factors that influence their retention. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 138, 161–176 (2009).

Chan, H. K. & Toyoizumi, T. An economic decision-making model of anticipated surprise with dynamic expectation. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2108.12347 (2021).

Clark, A. A nice surprise? Predictive processing and the active pursuit of novelty. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 17, 521–534 (2018).

Hsiung, A., Poh, J.-H., Huettel, S. A. & Adcock, R. A. Spoiler alert! Curiosity encourages patience and joy in the presence of uncertainty. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/x5hgc (2022).

Su-lin, G., Tuggle, C. A., Mitrook, M. A., Coussement, S. H. & Zillman, D. The thrill of a close game: who enjoys it and who doesn’t? J. Sport Soc. Issues 21, 53–64 (1997).

Ely, J., Frankel, A. & Kamenica, E. Suspense and surprise. J. Political Econ. 123, 215–260 (2015).

Geana, A., Wilson, R. C., Daw, N. & Cohen, J. D. Boredom, information seeking and exploration. in Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (eds Papafragou, A. et al.) 1751–1756 (Cognitive Science Society, 2016).

Cikara, M., Botvinick, M. M. & Fiske, S. T. Us versus them: social identity shapes neural responses to intergroup competition and harm. Psych. Sci. 22, 306–313 (2011).

Otto, A. R., Fleming, S. M. & Glimcher, P. W. Unexpected but incidental positive outcomes predict real-world gambling. Psych. Sci. 27, 299–311 (2016).

Otto, A. R. & Eichstaedt, J. C. Real-world unexpected outcomes predict city-level mood states and risk-taking behavior. PloS ONE 13, e0206923 (2018).

Villano, W. J., Otto, A. R., Chiemeka Ezie, C. E., Gillis, R. & Heller, A. S. Temporal dynamics of real-world emotion are more strongly linked to prediction error than outcome. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 149, 1755–1766 (2020).

Bhatia, S., Mellers, B. & Walasek, L. Affective responses to uncertain real-world outcomes: sentiment change on Twitter. PLoS ONE 14, e0212489 (2019).

Feather, N. T. Valence of outcome and expectation of success in relation to task difficulty and perceived locus of control. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 7, 372–386 (1967).

Verinis, J. S., Brandsma, J. M. & Cofer, C. N. Discrepancy from expectation in relation to affect and motivation: tests of Mcclelland’S hypothesis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 9, 47–58 (1968).

Ben-Yakov, A., Smith, V. & Henson, R. The limited reach of surprise: evidence against effects of surprise on memory for preceding elements of an event. Psychonomic Bull. Rev. 29, 1053–1064 (2021).

Gershman, S. J. & Daw, N. D. Reinforcement learning and episodic memory in humans and animals: an integrative framework. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 68, 101–128 (2017).

Knutson, B., Taylor, J., Kaufman, M., Peterson, R. & Glover, G. Distributed neural representation of expected value. J. Neurosci. 25, 4806–4812 (2005).

Hastorf, A. H. & Cantril, H. Case reports they saw a game: a case study. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 49, 129–134 (1951).

Huff, M. et al. Fandom biases retrospective judgments not perception. Sci. Rep. 7, 43083 (2017).

Price, P. C. Wishful thinking in the prediction of competitive outcomes. Think. Reason. 6, 161–172 (2000).

Marks, R. W. The effect of probability, desirability, and ‘privilege’ on the stated expectations of children. J. Personal. 19, 332–351 (1951).

Irwin, F. W. Stated expectations as functions of probability and desirability of outcomes. J. Personal. 21, 329–335 (1953).

Irwin, F. W. & Snodgrass, J. G. Effects of independent and dependent outcome values upon bets. J. Exp. Psychol. 71, 282–285 (1966).

Bell, D. E. Disappointment in decision making under uncertainty. Op. Res. 33, 1–27 (1985).

Rainey, D. W., Larsen, J. & Yost, J. H. Disappointment theory and disappointment among baseball fans. J. Sport Behav. 32, 339–356 (2009).

Van Dijk, W. The impact of probability and magnitude of outcome on disappointment and elation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 69, 277–284 (1997).

Kahneman, D. & Friedman, D. The psychology of preferences. Sci. Am. 246, 160–173 (1981).

Reid, R. L. The psychology of the near miss. J. Gambl. Behav. 2, 32–39 (1986).

Clark, L., Lawrence, A. J., Astley-Jones, F. & Gray, N. Gambling near-misses enhance motivation to gamble and recruit win-related brain circuitry. Neuron 61, 481–490 (2009).

Ong, D. C., Goodman, N. D. & Zaki, J. Near-misses sting even when they are uncontrollable. in Proceedings of the 37th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, CogSci 2015 (eds David C. Noelle, D. C. et al.) 339–356 (Cognitive Science Society, 2015).

Medvec, V. H., Madey, S. F. & Gilovich, T. When less is more: counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic medalists. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 69, 603–610 (1995).

Clark, L., Crooks, B., Clarke, R., Aitken, M. R. F. & Dunn, B. D. Physiological responses to near-miss outcomes and personal control during simulated gambling. J. Gambl. Stud. 28, 123–137 (2012).

Mellers, B. A., Schwartz, A., Ho, K. & Ritov, I. Decision affect theory: emotional reactions to the outcomes of risky options. Psych. Sci. 8, 423–429 (1997).

Sutton, R. S & Barto, A. G. Introduction to Reinforcement Learning 2nd edn (MIT Press, 1998).

Gershman, S. J., Moore, C. D., Todd, M. T. & Norman, K. A. The successor representation and temporal context. Neural Comput. 24, 1553–1568 (2012).

Dayan, P. Improving generalization for temporal difference learning: the successor representation. Neural Comput. 5, 613–624 (1993).

Newsome, W. T., Britten, K. H. & Movshon, J. A. Neuronal correlates of a perceptual decision. Nature 341, 52–54 (1989).

Brunton, B. W., Botvinick, M. M. & Brody, C. D. Rats and humans can optimally accumulate evidence for decision-making. Science 340, 95–98 (2013).

Pinto, L., Tank, D. W. & Brody, C. D. Multiple timescales of sensory-evidence accumulation across the dorsal cortex. eLife 11, e70263 (2022).

Morcos, A. S. & Harvey, C. D. History-dependent variability in population dynamics during evidence accumulation in cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1672–1681 (2017).

Akrami, A., Kopec, C. D., Diamond, M. E. & Brody, C. D. Posterior parietal cortex represents sensory history and mediates its effects on behaviour. Nature 554, 368–372 (2018).

Chao, Z. C., Takaura, K., Wang, L., Fujii, N. & Dehaene, S. Large-scale cortical networks for hierarchical prediction and prediction error in the primate brain. Neuron 100, 1252–1266.e3 (2018).

Wacongne, C. et al. Evidence for a hierarchy of predictions and prediction errors in human cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20754–20759 (2011).

Hwang, E. J., Dahlen, J. E., Mukundan, M. & Komiyama, T. History-based action selection bias in posterior parietal cortex. Nat. Commun. 8, 1242 (2017).

Baldassano, C. et al. Discovering event structure in continuous narrative perception and memory. Neuron 95, 709–721.e5 (2017).

Folkerts, S., Rutishauser, U. & Howard, M. W. Human episodic memory retrieval is accompanied by a neural contiguity effect. J. Neurosci. 38, 4200–4211 (2018).

Tsao, A. et al. Integrating time from experience in the lateral entorhinal cortex. Nature 561, 57–62 (2018).

Bright, I. M. et al. A temporal record of the past with a spectrum of time constants in the monkey entorhinal cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 20274–20283 (2020).

Hasson, U., Furman, O., Clark, D., Dudai, Y. & Davachi, L. Enhanced intersubject correlations during movie viewing correlate with successful episodic encoding. Neuron 57, 452–462 (2008).

Honey, C. J. et al. Slow cortical dynamics and the accumulation of information over long timescales. Neuron 76, 423–434 (2012).

Wise, R. A. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 483–494 (2004).

Nour, M. M. et al. Dopaminergic basis for signaling belief updates, but not surprise, and the link to paranoia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E10167–E10176 (2018).

Starkweather, C. K., Babayan, B. M., Uchida, N. & Gershman, S. J. Dopamine reward prediction errors reflect hidden-state inference across time. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 581–589 (2017).

Bromberg-Martin, E. S., Matsumoto, M., Nakahara, H. & Hikosaka, O. Multiple timescales of memory in lateral habenula and dopamine neurons. Neuron 67, 499–510 (2010).

Kim, H. R. et al. A unified framework for dopamine signals across timescales. Cell 183, 1600–1616 (2020).

Davachi, L. Item, context and relational episodic encoding in humans. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16, 693–700 (2006).

Eichenbaum, H., Yonelinas, A. P. & Ranganath, C. The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 123–152 (2007).

Pritzel, A. et al. Neural episodic control. In Proc. 34th International Conference on Machine Learning 2827–2836 (PMLR, 2016).

Ritter, S. et al. Been there, done that: meta-learning with episodic recall. In Proc. 35th International Conference on Machine Learning 4354–4363 (2018).

Lu, Q., Hasson, U. & Norman, K. A. A neural network model of when to retrieve and encode episodic memories. eLife 11, e74445 (2022).

Lengyel, M. & Dayan, P. Hippocampal contributions to control: the third way. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 20, 889–896 (2008).

Tulving, E. & Pearlstone, Z. Availability versus accessibility of information in memory for words. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 5, 381–391 (1966).

Congleton, A. R. & Berntsen, D. The devil is in the details: investigating the influence of emotion on event memory using a simulated event. Psych. Res. 84, 2339–2353 (2020).

Braun, E. K., Wimmer, G. E. & Shohamy, D. Retroactive and graded prioritization of memory by reward. Nat. Commun. 9, 4886 (2018).

Mather, M. & Sutherland, M. R. Arousal-biased competition in perception and memory. Perspect. Psych. Sci. 6, 114–133 (2011).

Bennion, K. A., Ford, J. H., Murray, B. D. & Kensinger, E. A. Oversimplification in the study of emotional memory. J. Int. Neuropsych. Soc. 19, 953–961 (2013).

Talarico J. M. & Rubin, D. C. (eds) in Flashbulb Memories 73–95 (Routledge, 2017).

Henson, R. N. & Gagnepain, P. Predictive, interactive multiple memory systems. Hippocampus 1326, 1315–1326 (2010).

Quent, J. A., Henson, R. N. & Greve, A. A predictive account of how novelty influences declarative memory. Neurobiol. Learning Mem. 179, 107382 (2021).

Kintsch, W. Learning from text, levels of comprehension, or: why anyone would read a story anyway?. Poetics 9, 87–98 (1980).

Reisenzein, R., Horstmann, G. & Schutzwohl, A. The cognitive-evolutionary model of surprise: a review of the evidence. Top. Cogn. Sci. 11, 50–74 (2019).

Modirshanechi, A., Brea, J. & Gerstner, W. A taxonomy of surprise definitions. J. Math. Psychol. 110, 102712 (2022).

Gold, B. P. et al. Musical reward prediction errors engage the nucleus accumbens and motivate learning. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 3310–3315 (2019).

Tobin, V. Elements of Surprise: Our Mental Limits and the Satisfactions of Plot (Harvard Univ. Press, 2018).

Bermejo-Berros, J., Lopez-Diez, J. & Gil Martínez, M. A. Inducing narrative tension in the viewer through suspense, surprise, and curiosity. Poetics 93, 101664 (2022).

Botzung, A., Rubin, D. C., Miles, A., Cabeza, R. & Labar, K. S. Mental hoop diaries: emotional memories of a college basketball game in rival fans. J. Neurosci. 30, 2130–2137 (2010).

Bernhardt, P. C., Dabbs, J. M., Fielden, J. A. & Lutter, C. D. Testosterone changes during vicarious experiences of winning and losing among fans at sporting events. Physiol. Behav. 65, 59–62 (1998).

Tomita, T. M., Barense, M. D. & Honey, C. J. The similarity structure of real-world memories. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.28.428278 (2021).

Breslin, C. W. & Safer, M. A. Effects of event valence on long-term memory for two baseball championship games. Psychol. Sci. 22, 1408–1412 (2011).

Talarico, J. M. & Moore, K. M. Memories of ‘The Rivalry’: dsifferences in how fans of the winning and losing teams remember the same game. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 756, 746–756 (2012).

Schmolck, H., Buffalo, E. A. & Squire, L. R. Memory distortions develop over time: recollections of the O.J. Simpson trial verdict after 15 and 32 months. Psychol. Sci. 11, 39–45 (2000).

Stern, H. A Brownian motion model for the progress of sports scores. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 89, 1128–1134 (1994).

Soligard, T. et al. How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. Br. J. Sports Med. 50, 1030–1041 (2016).

Teramoto, M. et al. Game injuries in relation to game schedules in the National Basketball Association. J. Sci. Med. Sport 20, 230–235 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The following individuals assisted with data collection and scoring: J. V. Figueroa, T. Guerra, J. Henige, N. Saito and M. Smith. We thank E. Robinson and B. Holladay for help with statistics. We received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W.A. conceived, programmed and analysed data from the experiment, and drafted the manuscript. J.V.D. and J.R.M. contributed to study design and scored a large portion of the recall data. A.J.B. contributed to study design. K.A.B. contributed to study design and coordinated all data collection.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Alyssa Sinclair, Hal Stern and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Extra participant response attributes.

(a) Distribution of responses for each team combined for plays, games, and seasons. (b, c) Memory ages. Data were collected over the course of 9 months, so as an alternative to Fig. 1c,d, we plotted the time in days between the game date and study date for plays and games (b) or the time in years between the season start and study date (c).

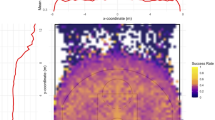

Extended Data Fig. 2 Full win probability model.

(a, b) We plotted win probability by expected home minus away score difference and game time remaining when the home (a) and away (b) teams had possession of the ball. To illustrate the importance of team possession, we also plotted the contrast of home possession minus away possession (c). All graphs show data only from the 4th quarter of games.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Prediction algorithm validation against an expert.

Play surprise values from our algorithm correlated strongly with those from an expert.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Unsigned surprise over time across a game.

(a, b) We plotted the mean (a) and standard deviation of unsigned surprise (b) against game time using our metric. Mean surprise had momentary troughs and peaks at the beginning and end of each game, likely due to the momentary decrease and increase in shots taken within these short time frames. Interestingly, mean surprise tended to decrease throughout the game, owing to the probability that the outcome of many basketball games would be nearly decided at that point. However, standard deviation increased exponentially until the end of games, due to the combination of games with a near-certain outcome, which have almost no surprise, and close games, which involve increasingly rapid swings in win probability as one nears the finish.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Prediction algorithm validations related to game memories.

Signed full-game (a) and within-game surprise (b) values correlated strongly with those from an expert site. Similarly, full-game surprise values from the algorithm correlated strongly with those based on pre-game Las Vegas betting odds data (c).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Control analyses ruling out maximum play surprise as an alternative explanation for game surprise findings.

(a) Maximum unsigned play surprise within a game was greater for the positive and negative games chosen by participants than a null distribution of all games (left) [positive vs. null Mann-Whitney U = 6.9*10^5, p = 0.002, r = 0.20, 95% confidence interval: (−0.03,−0.007); negative vs. null Mann-Whitney U = 5.8*10^5, p < 0.001, r = 0.30, 95% confidence interval: (−0.05,−0.02)]. We therefore selected subsets of the positive and negative games that did not differ from the null distribution (right) (p > 0.10, enforced). (b) Using these modified distributions, negative games still had greater unsigned full-game (left) and within-game surprise (right) values than the null distribution (99% and 100% of the samples, respectively). Shown are averages across resamples. (c, d) We plotted the t-statistics of subsets of the game data that did not differ significantly in maximum play surprise. (c) t-statistics for positive (top) and negative (bottom) full-game surprise. (d) t-statistics for positive (top) and negative (bottom) within-game surprise. Both negative distributions remained significant, whereas both positive ones were not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Season surprise after adjusting for differences in maximum full- and within-game surprise.

(a–d) We plotted the t-statistics of subsets of the season data that did not differ from the null distribution in maximum game surprise. (a-b) t-statistics for positive (a) and negative (b) seasons, adjusting for maximum full-game surprise. (c-d) t-statistics for positive (c) and negative (d) seasons, adjusting for within-game maximum surprise. All distributions remained significant after adjusting for game surprise deviations from the null.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Characteristics of participant memories.

We plotted metrics for each type of memory on (a) how long fans were affected by the outcome (1=minutes, 2=hours, 3=days, 4=months, 5=still affected), (b) emotionality with respect to everyday life (−5 to 5; worst to best thing that happened on a given day, week, month, year, ever), (c) unsigned emotionality, (d) their level of fandom (1=almost indifferent, 2=preferred team in that sport, 3=favorite team in that sport, 4=favourite team in any sport), and (e) approximate number of times they re-watched the play, parts of the game, or parts of the season.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Antony, J.W., Van Dam, J., Massey, J.R. et al. Long-term, multi-event surprise correlates with enhanced autobiographical memory. Nat Hum Behav 7, 2152–2168 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01631-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01631-8

This article is cited by

-

Adaptive compression as a unifying framework for episodic and semantic memory

Nature Reviews Psychology (2025)

-

Schemas, reinforcement learning and the medial prefrontal cortex

Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2025)

-

Brain network dynamics predict moments of surprise across contexts

Nature Human Behaviour (2024)