Abstract

Acanthocephala (thorny-headed worms), characterized by the presence of an eversible proboscis with hooks, are a diverse endoparasitic group that infect a wide range of vertebrates and invertebrates1. Although long regarded as a separate phylum, they have several putative sister taxa based on morphological features, including Platyhelminthes (flatworms)2, Priapulida (penis worms)3 and Rotifera (wheel animals)4. Molecular phylogenies have instead recovered them within rotifers5,6,7,8,9,10, suggesting acanthocephalans are derived from free-living worms with a jaw apparatus (Gnathifera). Their only fossil record is Late Cretaceous eggs11, contributing limited palaeontological information to deciphering their early evolution. Here we describe an acanthocephalan body fossil, Juracanthocephalus daohugouensis gen. et. sp. nov., from the Middle Jurassic Daohugou biota of China. Juracanthocephalus shows unambiguous acanthocephalan characteristics, for example a hooked proboscis, a bursa, as well as a jaw apparatus with discrete elements that is typical of other gnathiferans. Juracanthocephalus shares features with Seisonidea (an epizoic member of Rotifera) and Acanthocephala, bridging the evolutionary gap between jawed rotifers and the obligate parasitic, jawless acanthocephalans. Our results reveal previously unrecognized ecological and morphological diversity in ancient Acanthocephala and highlight the significance of transitional fossils, revealing the origins of this highly enigmatic group of living organisms.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data analysed in this paper, including the phylogenetic datasets, are available as part of the Article, Extended Data Figs. 1–6 or the Supplementary Information. The nomenclature of J. daohugouensis gen. et sp. nov. has been registered at ZooBank (LSID, urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:4F294930-AE20-45E4-A9E2-8FC96919B56B).

References

Kennedy, C. R. Ecology of the Acanthocephala (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006).

Van Cleave, H. J. Relationships of the Acanthocephala. Am. Nat. 75, 31–47 (1941).

Conway Morris, S. & Crompton, D. W. T. The origins and evolution of the Acanthocephala. Biol. Rev. 57, 85–115 (1982).

Ahlrichs, W. H. Epidermal ultrastructure of Seison nebaliae and Seison annulatus, and a comparison of epidermal structures within the Gnathifera. Zoomorphology 117, 41–48 (1997).

Garey, J. R., Near, T. J., Nonnemacher, M. R. & Nadler, S. A. Molecular evidence for Acanthocephala as a subtaxon of Rotifera. J. Mol. Evol. 43, 287–292 (1996).

Herlyn, H., Piskurek, O., Schmitz, J., Ehlers, U. & Zischler, H. The syndermatan phylogeny and the evolution of acanthocephalan endoparasitism as inferred from 18S rDNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 26, 155–164 (2003).

Sørensen, M. V. & Giribet, G. A modern approach to rotiferan phylogeny: combining morphological and molecular data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 40, 585–608 (2006).

Wey-Fabrizius, A. R. et al. Transcriptome data reveal syndermatan relationships and suggest the evolution of endoparasitism in Acanthocephala via an epizoic stage. PLoS ONE 9, e88618 (2014).

Laumer, C. E. et al. Spiralian phylogeny informs the evolution of microscopic lineages. Curr. Biol. 25, 2000–2006 (2015).

Sielaff, M. et al. Phylogeny of Syndermata (syn. Rotifera): mitochondrial gene order verifies epizoic Seisonidea as sister to endoparasitic Acanthocephala within monophyletic Hemirotifera. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 96, 79–92 (2016).

Cardia, D. F. F., Bertini, R. J., Camossi, L. G. & Letizio, L. A. First record of Acanthocephala parasites eggs in coprolites preliminary assigned to Crocodyliformes from the Adamantina Formation (Bauru Group, Upper Cretaceous), São Paulo, Brazil. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 91, e20170848 (2019).

Smith, M. R., Harvey, T. H. P. & Butterfield, N. J. The macro- and microfossil record of the Cambrian priapulid. Ottoia. Palaeontology 58, 705–721 (2015).

Giribet, G. & Edgecombe, G. D. Current understanding of Ecdysozoa and its internal phylogenetic relationships. Integr. Comp. Biol. 57, 455–466 (2017).

Smith, M. R. A palaeoscolecid worm from the Burgess Shale. Palaeontology 58, 973–979 (2015).

Palm, H. W. The Trypanorhyncha Diesing, 1863 (PKSPL-IPB, 2004).

Wang, S. et al. High-resolution taphonomic and palaeoecological analyses of the Jurassic Yanliao Biota of the Daohugou area, northeastern China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 530, 200–216 (2019).

Yang, J., Smith, M. R., Zhang, X.-G. & Yang, X.-Y. Introvert and pharynx of Mafangscolex, a Cambrian palaeoscolecid. Geol. Mag. 157, 2044–2050 (2020).

Howard, R. J., Parry, L. A., Clatworthy, I., D’Souza, L. & Edgecombe, G. D. Palaeoscolecids from the Ludlow Series of Leintwardine, Herefordshire (UK): the latest occurrence of palaeoscolecids in the fossil record. Pap. Palaeontol. 10, e1558 (2024).

Luo, C. et al. Exceptional preservation of a marine tapeworm tentacle in Cretaceous amber. Geology 52, 497–501 (2024).

Fonseca, M. C. G. D. et al. Acanthocephalan parasites of the flounder species Paralichthys isosceles, Paralichthys patagonicus and Xystreurys rasile from Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. V. 28, 346–359 (2019).

Bekkouche, N. & Gąsiorowski, L. Careful amendment of morphological data sets improves phylogenetic frameworks: re-evaluating placement of the fossil Amiskwia sagittiformis. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 20, 1–14 (2022).

Herlyn, H. in The Evolution and Fossil Record of Parasitism: Identification and Macroevolution of Parasites (eds De Baets, K. & Huntley, J. W.) 273–313 (Springer International Publishing, 2021).

Ahlrichs, W. H. Zur Ultrastruktur und Phylogenie von Seison nebaliae Grube, 1859 und Seison annulatus Claus, 1876. Hypothesen zu phylogenetischen Verwandtschaftsverhältnissen innerhalb der Bilateria (Georg-August-Univ., 1995).

Vasilikopoulos, A. et al. Whole-genome analyses converge to support the Hemirotifera hypothesis within Syndermata (Gnathifera). Hydrobiologia 851, 2795–2826 (2024).

Melone, G., Ricci, C., Segers, H. & Wallace, R. L. Phylogenetic relationships of phylum Rotifera with emphasis on the families of Bdelloidea. Hydrobiologia 387, 101–107 (1998).

Mauer, K. M. et al. Genomics and transcriptomics of epizoic Seisonidea (Rotifera, syn. Syndermata) reveal strain formation and gradual gene loss with growing ties to the host. BMC Genomics 22, 604 (2021).

Hagemann, L., Mauer, K. M., Hankeln, T., Schmidt, H. & Herlyn, H. Nuclear genome annotation of wheel animals and thorny-headed worms: inferences about the last common ancestor of Syndermata (Rotifera s.l.). Hydrobiologia 851, 2827–2844 (2023).

Ferraguti, M. & Melone, G. Spermiogenesis in Seison nebaliae (Rotifera, Seisonidea): further evidence of a rotifer-acanthocephalan relationship. Tissue Cell 31, 428–440 (1999).

Struck, T. H. et al. Platyzoan paraphyly based on phylogenomic data supports a noncoelomate ancestry of Spiralia. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 1833–1849 (2014).

Clément, P. The phylogeny of rotifers: molecular, ultrastructural and behavioural data. Hydrobiologia 255, 527–544 (1993).

Ricci, C. Are lemnisci and proboscis present in the Bdelloidea? Hydrobiologia 387, 93–96 (1998).

Sørensen, M. V. On the evolution and morphology of the rotiferan trophi, with a cladistic analysis of Rotifera. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 40, 129–154 (2002).

Koch, N. M. & Parry, L. A. Death is on our side: paleontological data drastically modify phylogenetic hypotheses. Syst. Biol. 69, 1052–1067 (2020).

De Baets, K., Dentzien-Dias, P., Harrison, G. W. M., Littlewood, D. T. J. & Parry, L. A. in The Evolution and Fossil Record of Parasitism: Identification and Macroevolution of Parasites (eds De Baets, K. & Huntley, J. W.) 231–271 (Springer International Publishing, 2021).

Verweyen, L., Klimpel, S. & Palm, H. W. Molecular phylogeny of the Acanthocephala (class Palaeacanthocephala) with a paraphyletic assemblage of the orders Polymorphida and Echinorhynchida. PLoS ONE 6, e28285 (2011).

Vinther, J. & Parry, L. A. Bilateral jaw elements in Amiskwia sagittiformis bridge the morphological gap between gnathiferans and chaetognaths. Curr. Biol. 29, 881–888 (2019).

Park, T.-Y. S. et al. A giant stem-group chaetognath. Sci. Adv. 10, eadi6678 (2024).

Sullivan, C. et al. The vertebrates of the Jurassic Daohugou Biota of northeastern China. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 34, 243–280 (2014).

Hejnol, A. in Evolutionary Developmental Biology of Invertebrates 2: Lophotrochozoa (Spiralia) (ed. Wanninger, A.) 1–12 (Springer, 2015).

Ricci, C., Melone, G. & Sotgia, C. Old and new data on Seisonidea (Rotifera). Hydrobiologia 255, 495–511 (1993).

Haustein, T., Lawes, M., Harris, E. & Chiodini, P. L. An eye-catching acanthocephalan. Clin. Microbiol. Infec. 16, 787–788 (2010).

Nickol, B. B. in Fish Diseases and Disorders, Volume 1: Protozoan and Metazoan Infections (ed. Woo, P. T. K.) 444–465 (CAB International, 2006).

Al-Jahdali, M. O., Hassanine, R. M. E.-S. & Touliabah, H. E.-S. The life cycle of Sclerocollum saudii Al-Jahdali, 2010 (Acanthocephala: Palaeacanthocephala: Rhadinorhynchidae) in amphipod and fish hosts from the Red Sea. J. Helminthol. 89, 277–287 (2015).

Cong, P. et al. Host-specific infestation in early Cambrian worms. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1465–1469 (2017).

Massini, J. G., Escapa, I. H., Guido, D. M. & Channing, A. First glimpse of the silicified hot spring biota from a new Jurassic chert deposit in the Deseado Massif, Patagonia, Argentina. Ameghiniana 53, 205–230 (2016).

Southcott, R. V. & Lange, R. T. Acarine and other microfossils from the Maslin Eocene, South Australia. Rec. S. Aust. Mus. 16, 1–21 (1971).

Poinar, G. O. & Ricci, C. Bdelloid rotifers in Dominican amber: evidence for parthenogenetic continuity. Experientia 48, 408–410 (1992).

Waggoner, B. M. & Poinar, G. O. Fossil habrotrochid rotifers in Dominican amber. Experientia 49, 354–357 (1993).

Near, T. J., Garey, J. R. & Nadler, S. A. Phylogenetic relationships of the Acanthocephala inferred from 18S ribosomal DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 10, 287–298 (1998).

Kapli, P., Yang, Z. & Telford, M. J. Phylogenetic tree building in the genomic age. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 428–444 (2020).

Huelsenbeck, J. P. & Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17, 754–755 (2001).

Lewis, P. O. A likelihood approach to estimating phylogeny from discrete morphological character data. Syst. Biol. 50, 913–925 (2001).

Swofford, D. L. PAUP*. [Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (and other methods)] v.4 (Sinauer Associates, 2003).

Goloboff, P. A. & Morales, M. E. TNT version 1.6, with a graphical interface for MacOS and Linux, including new routines in parallel. Cladistics 39, 144–153 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to H. Herlyn, H. Zhang, M. V. Sørensen, A. Rasnitsyn, J. Zhang and D. Zheng for helpful discussions and comments, Y. Fang for the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analyses and D. Yang for artistic reconstruction. We also thank M. Knoff for providing the image of S. sagittifer. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42125201 and 42293280) and the Jiangsu Innovation Support Plan for International Science and Technology Cooperation Programme (BZ2023068). This paper is a contribution to the IUGS “Deep-time Digital Earth” Big Science Program, Geobiodiversity Database. L.A.P. is supported by a NERC independent research fellowship (NE/W007878/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.W. designed the project. C.L., L.A.P. and B.E.B. carried out the phylogenetic analysis. S.W. conducted the SEM and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analyses. H.Z. and B.W. collected the specimen. C.L., L.A.P. and B.W. wrote the original draft with review and editing from B.E.B., S.W., E.A.J. and H.Z. All authors carried out the morphological analysis, discussed the results and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Tae-Yoon Park, Jakob Vinther and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Elemental analysis of holotype of J. daohugouensis gen. et sp. nov., NIGP206848.

a, Photograph in alcohol. b, Backscatter scanning electron (BSE) image under a scanning electronic microscope. c–h, Elemental maps of b from energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. c, Overlay image of element C (green colour), O (red colour), Al (blue colour), Si (purple colour), and K (yellow colour) concentrations. d, O map. e, Al map. f, Si map. g, K map. h, Fe map. i, EDS spectrum of the complete montage. Scale bar, 2.0 mm.

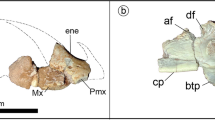

Extended Data Fig. 2 Proboscis of holotype of J. daohugouensis gen. et sp. nov., NIGP206848.

a–d, Elemental maps from energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. a, C map. b, O map. c, Si map. d, K map. e, Higher magnification of proboscis (dry), white arrows mark hooks. f, Higher magnification of mouth opening area (in alcohol). at, alimentary tract. All analyses were performed three times. Scale bars, 0.5 mm (a–d), 0.2 mm (e, f).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Phylogenetic tree from strict consensus tree of parsimony analysis.

a, Strict consensus tree including J. daohugouensis of 593 most parsimonious trees (410 scores each) from PAUP parsimony analysis (Methods), CI = 0.566, RI = 0.834. b, Strict consensus tree excluding J. daohugouensis of 659 most parsimonious trees (409 scores each) from PAUP parsimony analysis (Methods), CI = 0.567, RI = 0.833. The strict consensus tree fails to resolve the relationship between Seisonidea, Rotifera and Acanthophala when Juracanthocephalus is excluded.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Full list of apomorphies of Gnathifera.

Apomorphies are optimized computationally unless followed by an asterisk, which denotes an apomorphy suggested by our results but lacking sufficient sampling to optimise computationally. The apomorphic losses of Acanthocephala are also added. The topology is derived from the strict consensus tree based on a matrix of 68 taxa and 247 characters; the non-gnathiferans were omitted for clarity but were included in the analyses in which synapomorphies were optimised; the precise systematic position of Gnathostomulida has not been recovered in the strict consensus tree, but it is widely considered as the sister group of other gnathiferans. Yellow rectangles represent characters associated with jaw apparatus, green rectangles represent characters associated with gut (including mouth and anus), red rectangles represent characters associated with body shape, and grey rectangles represent characters associated with other body structures. Characters that can be observed in J. daohugouensis are in red colour, otherwise in black. Cross indicates extinct taxa.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Note 1

Characters used in phylogenetic analysis.

Supplementary Data 1

Matrix of the Bayesian approach.

Supplementary Data 2

Matrix of parsimony analyses using PAUP.

Supplementary Data 3

Matrix of parsimony analyses using TNT.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, C., Parry, L.A., Boudinot, B.E. et al. A Jurassic acanthocephalan illuminates the origin of thorny-headed worms. Nature 641, 674–680 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08830-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08830-5