Abstract

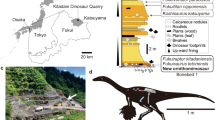

Eutyrannosaurians were large predatory dinosaurs that dominated Asian and North American terrestrial faunas in latest Cretaceous times. These apex predators arose from smaller-bodied tyrannosauroids during the ‘middle’ Cretaceous that are poorly known owing to the paucity of fossil material1,2,3. Here we report on a new tyrannosauroid, Khankhuuluu mongoliensis gen. et sp. nov., from lower Upper Cretaceous deposits of Mongolia that provides a new perspective on eutyrannosaurian origins and evolution. Phylogenetic analyses recover Khankhuuluu immediately outside Eutyrannosauria and recover the massive, deep-snouted Tyrannosaurini and the smaller, gracile, shallow-snouted Alioramini as highly derived eutyrannosaurian sister clades. Khankhuuluu and the late-diverging Alioramini independently share features related to a shallow skull and gracile build with juvenile eutyrannosaurians, reinforcing the key role heterochrony had in eutyrannosaurian evolution. Although eutyrannosaurians were mainly influenced by peramorphosis or accelerated growth4,5,6,7,8,9,10, Alioramini is revealed as a derived lineage that retained immature features through paedomorphosis and is not a more basal lineage as widely accepted11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Our results reveal that Asian tyrannosauroids (similar to Khankhuuluu) dispersed to North America, giving rise to Eutyrannosauria in the mid-Late Cretaceous. Eutyrannosauria diversified and remained exclusively in North America until a single dispersal to Asia in the latest Cretaceous that established Alioramini and Tyrannosaurini. Stark morphological differences between Alioramini and Tyrannosaurini probably evolved due to divergent heterochronic trends—paedomorphosis versus peramorphosis, respectively—allowing them to coexist in Asia and occupy different ecological niches.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data files relevant to our analyses and results are provided in the Article, its Supplementary Information and at Dryad59 (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fj6q5744h). These files include our phylogenetic character dataset (.xlsx and .nex), phylogenetic characters illustrated graphically (.pdf), rationalization of cut-off values used for proportional characters (.xlsx), resultant tree files (.tre) and a file (log.txt) providing Templeton’s test results. The holotype and referred specimens of K. mongoliensis are catalogued and available for study to qualified researchers at the Institute of Paleontology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

Code availability

All R scripts and corresponding data files for replication of our time-calibration and ancestral state estimation used to reproduce our results are provided in the Supplementary Information and in the associated source data files located at Dryad59 (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fj6q5744h).

References

Brusatte, S. L., Averianov, A., Sues, H.-D., Muir, A. & Butler, I. B. New tyrannosaur from the mid-Cretaceous of Uzbekistan clarifies evolution of giant body sizes and advanced senses in tyrant dinosaurs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 3447–3452 (2016).

Nesbitt, S. J. et al. A mid-Cretaceous tyrannosauroid and the origin of North American end-Cretaceous dinosaur assemblages. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 892–899 (2019).

Zanno, L. E. et al. Diminutive fleet-footed tyrannosauroid narrows the 70-million-year gap in the North American fossil record. Commun. Biol. 2, 64 (2019).

Long, J. A. & McNamara, K. J. in Evolutionary Change and Heterochrony (ed. McNamara, K. J.) 151–168 (Wiley, 1995).

Long, J. A. & McNamara, K. J. in Dinofest International. Proceedings of a Symposium held at Arizona State University (eds. Wolberg, D. L. et al.) 113–123 (Academy of Natural Sciences, 1997).

Erickson, G. M. Assessing dinosaur growth patterns: a microscopic revolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 677–684 (2005).

Erickson, G. M. et al. Gigantism and comparative life-history parameters of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs. Nature 430, 772–775 (2004).

Cullen, T. M. et al. Osteohistological analyses reveal diverse strategies of theropod dinosaur body-size evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20202258 (2020).

Voris, J. T. et al. Two exceptionally preserved juvenile specimens of Gorgosaurus libratus (Tyrannosauridae, Albertosaurinae) provide new insight into the timing of ontogenetic changes in tyrannosaurids. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 41, e2041651 (2022).

D’Emic, M. D. et al. Developmental strategies underlying gigantism and miniaturization in non-avialan theropod dinosaurs. Science 379, 811–814 (2023).

Holtz Jr, T. R. in Mesozoic Vertebrate Life (eds Tanke, D. H. et al.) 64–83 (Indiana Univ. Press, 2001).

Brusatte, S. L., Carr, T. D., Erickson, G. M., Bever, G. S. & Norell, M. A. A long-snouted, multihorned tyrannosaurid from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 17261–17266 (2009).

Brusatte, S. L. et al. Tyrannosaur paleobiology: new research on ancient exemplar organisms. Science 329, 1481–1485 (2010).

Loewen, M. A., Irmis, R. B., Sertich, J. J. W., Currie, P. J. & Sampson, S. D. Tyrant dinosaur evolution tracks the rise and fall of Late Cretaceous oceans. PLoS ONE 8, e79420 (2013).

Lü, J. et al. A new clade of Asian Late Cretaceous long-snouted tyrannosaurids. Nat. Commun. 5, 3788 (2014).

Brusatte, S. L. & Carr, T. D. The phylogeny and evolutionary history of tyrannosauroid dinosaurs. Sci. Rep. 6, 20252 (2016).

Carr, T. D., Varricchio, D. J., Sedlmayr, J. C., Roberts, E. M. & Moore, J. R. A new tyrannosaur with evidence for anagenesis and crocodile-like facial sensory system. Sci. Rep. 7, 44942 (2017).

Voris, J. T., Therrien, F., Zelenitsky, D. K. & Brown, C. M. A new tyrannosaurine (Theropoda:Tyrannosauridae) from the Campanian Foremost Formation of Alberta, Canada, provides insight into the evolution and biogeography of tyrannosaurids. Cretac. Res. 110, 104388 (2020).

Dalman, S. G. et al. A giant tyrannosaur from the Campanian–Maastrichtian of southern North America and the evolution of tyrannosaurid gigantism. Sci. Rep. 14, 22124 (2024).

Delcourt, R. & Grillo, O. N. Tyrannosauroids from the Southern Hemisphere: implications for biogeography, evolution, and taxonomy. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 511, 379–387 (2018).

Gignac, P. M. & Erickson, G. M. The biomechanics behind extreme osteophagy in Tyrannosaurus rex. Sci. Rep. 7, 2012 (2017).

Tanaka, K., Anvarov, O. U. O., Zelenitsky, D. K., Ahmedshaev, A. S. & Kobayashi, Y. A new carcharodontosaurian theropod dinosaur occupies apex predator niche in the early Late Cretaceous of Uzbekistan. R. Soc. Open Sci. 8, 210923 (2021).

Perle, A. On the discovery of Alectrosaurus from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. Probl. Mong. Geol. 3, 104–113 (1977).

Carr, T. D. A reappraisal of tyrannosauroid fossils from the Iren Dabasu Formation (Coniacian–Campanian), Inner Mongolia, People’s Republic of China. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 42, e2199817 (2023).

Mader, B. J. & Bradley, R. L. A redescription and revised diagnosis of the syntypes of the Mongolian tyrannosaur Alectrosaurus olseni. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 9, 41–55 (1989).

Gilmore, C. W. On the dinosaurian fauna of the Iren Dabasu Formation. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 67, 23–95 (1933).

Van Itterbeeck, J., Horne, D. J., Bultynck, P. & Vandenberghe, N. Stratigraphy and palaeoenvironment of the dinosaur-bearing Upper Cretaceous Iren Dabasu Formation, Inner Mongolia, People’s Republic of China. Cretac. Res. 26, 699–725 (2005).

Holtz Jr, T. R. in The Dinosauria (eds Weishampel, D. B. et al.) 111–136 (Univ. California Press, 2004).

Brochu, C. A. Osteology of Tyrannosaurus rex: insights from a nearly complete skeleton and high-resolution computed tomographic analysis of the skull. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 22, 1–138 (2003).

Averianov, A. & Sues, H.-D. Skeletal remains of Tyrannosauroidea (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Bissekty Formation (Upper Cretaceous: Turonian) of Uzbekistan. Cretac. Res. 34, 284–297 (2012).

von Huene, F. Das natürliche system der Saurischia. Zentralbl. Mineral. Geol. Paläontol. B 1914, 154–158 (1914).

Gauthier, J. A. Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds. Mem. Calif. Acad. Sci. 8, 1–55 (1986).

Osborn, H. F. Tyrannosaurus and other Cretaceous carnivorous dinosaurs. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 21, 259–265 (1905).

Tsuihiji, T., Watabe, M., Tsogtbaatar, K., Barsbold, R. & Suzuki, S. A tyrannosauroid frontal from the Upper Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Santonian) of the Gobi Desert, Mongolia. Vertebr. Palasiat. 50, 102–110 (2012).

Averianov, A. & Sues, H.-D. Correlation of Late Cretaceous continental vertebrate assemblages in middle and central Asia. J. Stratigr. 36, 462–485 (2012).

Brusatte, S. L., Carr, T. D. & Norell, M. A. The osteology of Alioramus, a gracile and long-snouted tyrannosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 366, 1–197 (2012).

Foster, W. et al. The cranial anatomy of the long-snouted tyrannosaurid dinosaur Qianzhousaurus sinensis from the Upper Cretaceous of China. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 41, e1999251 (2022).

Carr, T. D. A high-resolution growth series of Tyrannosaurus rex obtained from multiple lines of evidence. PeerJ 8, e9192 (2020).

Carr, T. D. Craniofacial ontogeny in Tyrannosauridae (Dinosauria, Coelurosauria). J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 19, 497–520 (1999).

Currie, P. J. Allometric growth in tyrannosaurids (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of North America and Asia. Can. J. Earth Sci. 40, 651–665 (2003).

Currie, P. J. Cranial anatomy of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta,Canada. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 48, 191–226 (2003).

Tsuihiji, T. et al. Cranial osteology of a juvenile specimen of Tarbosaurus bataar (Theropoda, Tyrannosauridae) from the Nemegt Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of Bugin Tsav, Mongolia. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 31, 497–517 (2011).

Xu, X. et al. Basal tyrannosauroids from China and evidence for protofeathers in tyrannosauroids. Nature 431, 680–684 (2004).

Hutt, S., Naish, D., Martill, D. M., Barker, M. J. & Newbery, P. A preliminary account of a new tyrannosauroid theropod from the Wessex Formation (Early Cretaceous) of southern England. Cretac. Res. 22, 227–242 (2001).

Naish, D. & Cau, A. The osteology and affinities of Eotyrannus lengi, a tyrannosauroid theropod from the Wealden Supergroup of southern England. PeerJ 10, e12727 (2022).

Li, D., Norell, M. A., Gao, K.-Q., Smith, N. D. & Makovicky, P. J. A longirostrine tyrannosauroid from the Early Cretaceous of China. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 183–190 (2010).

Voris, J. T., Zelenitsky, D. K., Therrien, F. & Currie, P. J. Reassessment of a juvenile Daspletosaurus from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada with implications for the identification of immature tyrannosaurids. Sci. Rep. 9, 17801 (2019).

Benson, R. B. J. New information on Stokesosaurus, a tyrannosauroid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from North America and the United Kingdom. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 28, 732–750 (2008).

Brusatte, S. & Benson, R. The systematics of Late Jurassic tyrannosauroids (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from Europe and North America. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 58, 47–54 (2012).

Carr, T. D., Williamson, T. E. & Schwimmer, D. R. A new genus and species of tyrannosauroid from the Late Cretaceous (Middle Campanian) Demopolis Formation of Alabama. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 25, 119–143 (2005).

Brusatte, S. L., Benson, R. B. J. & Norell, M. A. The anatomy of Dryptosaurus aquilunguis (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and a review of Its tyrannosauroid affinities. Am. Mus. Novit. 3717, 1–53 (2011).

Currie, P. J., Hurum, R. H. & Sabath, K. Skull structure and evolution in tyrannosaurid dinosaurs. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 48, 227–234 (2003).

Carr, T. D. & Williamson, T. E. Diversity of late Maastrichtian Tyrannosauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from western North America. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 142, 479–523 (2004).

Goloboff, P. A. & Morales, M. E. TNT version 1.6, with a graphical interface for MacOS and Linux, including new routines in parallel. Cladistics 39, 144–153 (2023).

Groh, S. S., Upchurch, P., Barrett, P. M. & Day, J. J. How to date a crocodile: estimation of neosuchian clade ages and a comparison of four time-scaling methods. Palaeontology 65, e12589 (2022).

Bapst, D. W. A stochastic rate-calibrated method for time-scaling phylogenies of fossil taxa. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 724–733 (2013).

Lloyd, G. T., Bapst, D. W., Friedman, M. & Davis, K. E. Probabilistic divergence time estimation without branch lengths: dating the origins of dinosaurs, avian flight and crown birds. Biol. Lett. 12, 20160609 (2016).

Revell, L. J. phytools 2.0: an updated R ecosystem for phylogenetic comparative methods (and other things). PeerJ 12, e16505 (2024).

Voris, J. T et al. Data for ‘A new Mongolian tyrannosauroid and the evolution of Eutyrannosauria’. Dryad https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fj6q5744h (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank U. Sanjaadash and I. Damdinsuren for specimen access and assistance; P. Makovicky, X. Xing and J. Shu’an for photographs of specimens. D.K.Z. thanks the musician/guitarist Slash for his unwavering support and encouragement. Funding was provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Discovery Grant (RGPIN 04854) to D.K.Z., the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (JP23K03557) to Y.K., and by an Izaak Walton Killam Memorial Research Scholarship to J.T.V.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.T.V. and D.K.Z. conceived and designed the project. J.T.V. and D.K.Z. collected and compiled data and performed analyses. Y.K., S.P.M., F.T, H.T., T.C. and K.T. provided data and support for analyses. The original manuscript draft was written by J.T.V. and D.K.Z. All of the authors contributed to manuscript revisions. J.T.V., D.K.Z., Y.K., H.T., T.C. and K.T. examined key specimens.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Roger Benson, Mark Loewen and Darren Naish for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

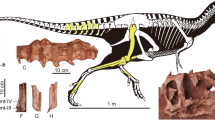

Extended Data Fig. 1 Diagnostic and phylogenetically significant characters of Khankhuuluu. Autapomorphies of Khankhuuluu in yellow.

Synapomorphies of Khankhuuluu+Eutyrannosauria or characters restricted to Eutyrannosauria in magenta. Nasals of Khankhuuluu MPC-D 100/50 (1a, 2a) and Gorgosaurus ROM 1247 (1b, 2b) in dorsal (1a, b) and ventral (2a, b) views. Quadratojugals of Khankhuuluu (3a) and Daspletosaurus (3b). Scapulocoracoid of Khankhuuluu MPC-D 100/50 (4a) and Albertosaurus TMP 1986.064.0001 (4b). Quadrates of Khankhuuluu MPC-D 100/50 (5a) and MPC-D 100/51 (6a) and Gorgosaurus TMP 1986.144.0001 (5b and 6b) in lateral (5) and posterior (6) views. Distal tibia of Khankhuuluu MPC-D 100/51 (7a) and Albertosaurus TMP 1986.064.0001 (7b) in anterior view. Scale bars = 5 cm. Abbreviations: aco, astragalar contact orientation changes across angle (unambiguous synapomorphy); edp, expanded dorsal process of quadratojugal; lcp, lacrimal cornual process; mfp, medial frontal process; npr, small nasal pneumatic recess present; nr, nasal rugosities; qf, quadrate foramen; qjc, quadratojugal contact medial margin; qr, quadrate recess; qrwa, quadrate recess aperture medial wall absent; qrwp, quadrate recess aperture medial wall present; sad, deep subacromial depression; sfp, supernumerary frontal processes present medial frontal process absent; sgf, subglenoid fossa ventral face present.

Extended Data Fig. 2

Cladogram with examples of Tyrannosaurinae skulls, including: a, Bistahieversor, b, Daspletosaurus, c, Alioramus (Alioramini), and d, Tyrannosaurus (Tyrannosaurini). Alioramini is supported as both a highly derived member of Tyrannosaurinae and as a sister taxon to the Tyrannosaurini by numerous unambiguous and exclusive synapomorphies. See Supplementary Information 8 for a full list of synapomorphies.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Phylogeny of Tyrannosauroidea following a priori pruning of taxa scoring for less than 20% of characters.

Taxa excluded from the comprehensive analysis depicted in Fig. 3 are Kileskus, Juratyrant, Sinotyrannus, Stokesososaurus, Timurlengia, Alectrosaurus, Dryptosaurus, Nanuqsaurus, Thanatotheristes, and Zhuchengtyrannus. Values adjacent to nodes denote node support values: Bremer supports (left values < 20), bootstrap indices (right values > 50). Bremer support values and bootstrap indices increase significantly for most clades relative to those clades in the comprehensive analysis in Fig. 3. Among derived tyrannosaurine taxa (e.g., Alioramini+Tyrannosaurini), higher node values are found here relative to similar positions in the comprehensive tree in Fig. 3. This reveals that lower overall support values in the comprehensive tree is primarily due to ambiguity incurred in character state transformations with the inclusion of highly fragmentary taxa, particularly in late-diverging tyrannosauroids (e.g., Nanuqsaurus [8.1% of characters scored], Thanatotheristes [19.0%] Zhuchengtyrannus [10.3%]).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supporting information for main text includes measurements and ontogenetic assessment for Khankhuuluu mongoliensis, supplementary discussions for the phylogenetic position of Alioramini, phylogenetic protocols including taxon and character omissions, character list, clade synapomorphies, Templeton’s test results, and additional tests of time calibration.

Supplementary Data

Character scoresheet: phylogenetic character scoresheet.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Voris, J.T., Zelenitsky, D.K., Kobayashi, Y. et al. A new Mongolian tyrannosauroid and the evolution of Eutyrannosauria. Nature 642, 973–979 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08964-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08964-6