Abstract

Subthreshold depression, defined as a depressive status falling short of the diagnostic threshold for major depression, is common, disabling and constitutes a risk factor for future depressive episodes. Cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) have been shown to be effective but are usually provided as packages of various skills. Little research has been done to investigate whether all their components are beneficial and contributory to mental health promotion. We addressed this issue by developing a smartphone CBT app that implements five representative CBT skills (behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, problem solving, assertion training and behavior therapy for insomnia), and conducting a master randomized study that included four 2 × 2 factorial trials to enable precise estimation of skill-specific efficacies. Between September 2022 and February 2024, we recruited 3,936 adult participants with subthreshold depression. Among those randomized, the follow-up rate was 97% at week 6 and adherence to the app was 84%. The study showed that all included CBT skills and their combinations differentially beat all three control conditions of delayed treatment, health information or self-check, with effect sizes ranging between −0.67 (95% confidence interval: −0.81 to −0.53) and −0.16 (−0.30 to −0.02) for changes in depressive symptom severity from baseline to week 6, as measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores. Knowledge of the active ingredients of CBT can better inform the design of more effective and scalable psychotherapies in the future. (UMIN Clinical Trials Registry UMIN000047124).

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Subthreshold depression, or mild depression falling short of the diagnostic threshold for major depressive disorder, is prevalent, persistent and disabling. Its prevalence is estimated to be around 11% across the world1. It often runs a fluctuating yet chronic course2,3. Subthreshold depression is associated with impaired social function and decreased quality of life4,5, increased use of health services6 and mortality7. Although these negative impacts may be less grave than those associated with fully syndromal major depression at the individual level, given the sheer prevalence of those affected, subthreshold depression is responsible for economic losses to society that are indeed comparable to those of major depressive disorder8. Moreover, people with subthreshold depression are three times more likely to develop a major depressive episode than those without1,9.

Subthreshold depression is responsive to treatments10, which can decrease the symptom burden, promote mental wellbeing and also decrease future major depressive episodes11,12. Current guidelines unanimously recommend psychotherapies, and cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) in particular, for people with subthreshold to mild major depression13,14. Given the prevalence of the condition and the human and time resources typically necessary for the face-to-face delivery of psychotherapies, digital delivery formats have received increasing attention in the past two decades15, and we now have strong evidence to show that internet CBT (iCBT) is effective for subthreshold depression16.

CBT, however, is typically provided as a package of variable combinations of cognitive and behavioral skills17, and we do not know whether all of them are contributory to mental health promotion. Such knowledge is indispensable in providing the most efficacious interventions in the most efficient way at scale in the population, because inefficacious and possibly harmful components can be dropped and more efficacious combinations can be prioritized. Efficiency and accessibility are particularly important to enhance psychological health especially among those who may feel hesitant about seeking professional help.

We therefore developed a self-help smartphone CBT app that contained modules for five representative CBT skills17: behavioral activation (BA), cognitive restructuring (CR), problem solving (PS), assertion training (AT) and behavior therapy for insomnia (BI). Briefly, BA aims to enhance mood by increasing engagement in pleasant activities, CR corrects the negative thoughts underlying depressed mood, PS teaches a structured approach to solving overwhelming problems at hand, AT helps articulate phrases to convey one’s wishes without hurting others’ feelings and in BI people learn and practice evidence-based efficient sleeping patterns.

We conducted a randomized controlled trial to estimate the specific efficacies of these CBT skills for adults with subthreshold depression in the general population. In this trial, dubbed the RESiLIENT trial (Resilience Enhancement with Smartphone in Living ENvironmeTs)18, we adopted a master protocol design for a randomized controlled trial because this offers the optimal design to evaluate multiple intervention components simultaneously against common controls19,20,21. Because we may need large sample sizes to make precise estimates of the efficacy of each individual skill, we embedded four 2 × 2 factorial trials using each skill as a factor to make efficient use of the sample size. This paper focuses on the acute intervention effects of the five CBT skills.

Results

Participant flow and study design

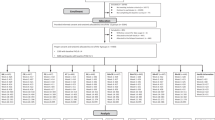

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants. Of 34,123 adults assessed for eligibility, 5,364 were judged eligible, provided informed consent and were randomized to one of the 12 intervention or control arms between 5 September 2022 and 21 February 2024. Two participants later withdrew their consent, and 1,426 had baseline Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores of ≤4, leaving 3,936 as the intention-to-treat cohort for this study, which met the preplanned sample size requirement. Participants were randomly allocated in equal proportions to one of these 12 arms.

The BA arm and control arm were common across the four 2 × 2 trials and are shown by the dotted squares in trials 2 to 4. The prespecified control condition was the delayed treatment. We conducted sensitivity analyses by replacing the delayed treatment with the health information arm and the self-check arm (Methods). aParticipants working on a three-shift schedule were excluded in the primary and sensitivity analyses for trial 4 (199 (5.1%) of the total sample were shift workers). AT, assertion training; BA, behavioral activation; BI, behavior therapy for insomnia; CR, cognitive restructuring; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PS, problem solving.

For the primary analysis, we embedded four 2 × 2 factorial trials. Factorial trial 1 evaluated BA and CR, trial 2 evaluated BA and PS, trial 3 evaluated BA and AT, and trial 4 evaluated BA and BI. The BA only arm and the control arm were common across the four 2 × 2 trials, thus enabling efficient use of the sample size. BA was prioritized because it was the most effective skill in the component network meta-analysis of iCBT17 and has increasingly been used in iCBT interventions aiming at scalability as BA alone or in a combination of BA plus PS16. Because there is no universally accepted gold standard control condition in psychotherapy trials22,23, we included three control conditions in the master protocol: in the delayed treatment condition, participants had to wait 6 weeks before they could start active interventions; the health information arm provided information about physical exercise, nutrition and oral health on the app; and in the self-check arm participants were only prompted to fill in the PHQ-9 on the app every week. The delayed treatment was the prespecified primary control arm, but we also included the health information and self-check arms for sensitivity analyses to test whether the primary results against the delayed treatment arm also held against controls with potentially different levels of stringency.

Participant disposition

Table 1 gives the baseline characteristics of all the included participants. The participants were mainly in their 30s, 40s and 50s, 51% were men and most were married and employed. Their mean baseline PHQ-9 score was 8.1 (s.d. 2.7), 17% had suspected problematic alcohol use, 29% had a history of mental health treatment and 33% had some physical comorbidities. Supplementary Table 1 compares the distribution of these variables between the presence and absence of each intervention in the factorial design trials and shows that they were well balanced.

Primary outcome

Table 2 shows the results of the primary analyses of changes in PHQ-9 scores from baseline to week 6 (the primary outcome) for each of the four 2 × 2 factorial trials using the delayed treatment arm as the control, as prespecified in the statistical analysis plan (SAP)24. In this primary analysis for each of the four factorial trials (for example, trial 1, which examined the two factors BA and CR) (Fig. 1), we estimated the efficacy of BA by comparing participants who had been allocated to that skill (for example, BA + CR or BA) with those who had not (for example, CR or delayed treatment) in a mixed-model repeated measures analysis (MMRM). The results showed that all CBT skills had specific efficacies when present compared with when the skills were absent. The standardized mean difference (SMD) was −0.38 (95% confidence interval (CI): −0.48 to −0.27, P = 5.3 × 10−13) for BA; −0.27 (−0.37 to −0.16, P = 2.9 × 10−7) for CR; −0.27 (−0.37 to −0.17, P = 1.8 × 10−7) for PS; −0.24 (−0.34 to −0.14, P = 2.2 × 10−6) for AT; and −0.27 (−0.37 to −0.16, P = 3.8 × 10−7) for BI.

Table 3 shows the prespecified sensitivity analysis, examining the interaction of the two interventions used in each of the 2 × 2 factorial trials as hypothesized in the protocol18 and the SAP24. Interactions between the two interventions were observed in all four trials. When interactions were taken account of, estimated SMDs for single-skill interventions varied from −0.52 (−0.66 to −0.38, P = 5.9 × 10−13) for PS to −0.65 (−0.79 to −0.51, P = 2.2 × 10−19) for BA, whereas those for two-skill interventions varied from −0.57 (−0.71 to −0.43, P = 7.7 × 10−15) for BA + BI to −0.67 (−0.81 to −0.53, P = 2.4 × 10−20) for BA + PS. Administering two skills did not double the efficacy of providing one skill because the interaction was antagonistic.

In the protocol18 and in the SAP24 we prespecified that although research so far has not been suggestive of interactions among iCBT components17,25, we would interpret the results considering the interaction if the analyses identified a strong interaction. We therefore conducted the following sensitivity analyses using more stringent control conditions of health information or self-check in each of the four 2 × 2 trials while including the interaction term (Extended Data Tables 1 and 2). The stronger control condition corresponded to a smaller estimated SMD. However, even when we used the most stringent control condition of self-check, we observed demonstrable specific efficacies for all the interventions, corresponding with SMDs of −0.16 (−0.30 to −0.02) for PS and −0.31 (−0.45 to −0.17) for BA + PS.

The combined analysis, which conducted MMRM for the pooled dataset encompassing the four factorial trials, provides a summary of all intervention arms contrasted against all of the control arms (Table 4). In the analysis of trial 4 we excluded participants on a three-shift work schedule as per the SAP because they were considered to be less likely to benefit from BI; however, we did not exclude these participants in the combined analysis and the effect estimates for BI were essentially unchanged. The 95% CIs for the SMDs of all interventions were below zero, or the point of null effect, against all controls. The three control conditions differentiated among themselves, showing that delayed treatment was the weakest control, followed by health information and self-check in that order.

Secondary outcomes

Supplementary Tables 2–4 show the results of analyses of the main and interaction effects using MMRM for the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale (GAD-7; anxiety), the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; insomnia) and the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS; mental wellbeing). Extended Data Tables 3–5 show the combined analyses for these three secondary outcomes. The health information arm was the strongest control for these outcomes.

With regard to anxiety (GAD-7), all interventions were superior to the delayed treatment or self-check controls. BA and BI were particularly efficacious for treating anxiety even when compared with the health information arm, showing SMDs of −0.24 (95% CI: −0.37 to −0.10) and −0.21 (−0.34 to −0.08), respectively. For insomnia (ISI), all interventions were superior to the delayed treatment and self-check controls, but only BI and BA + BI were superior to the health information with SMDs of −0.33 (−0.45 to −0.21) and −0.27 (−0.39 to −0.15), respectively. For mental wellbeing (SWEMWBS), almost all interventions were better than the delayed treatment control, but only BA, BI and BA + AT were better than the self-check control and none of the interventions were superior to the health information control. The SMDs of BA, BI or BA + AT over the self-check control were 0.15 (0.03 to 0.27), 0.17 (0.05 to 0.29) and 0.13 (0.01 to 0.24).

Adherence to program and completion of follow-up assessments

Participants actively engaged with the smartphone CBT app during the initial six weeks. The chapters that constituted the app differed by week in the amount of learning that was expected of users (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Participants spent an average 20–60 min on chapter 1 (when all active intervention arm participants were introduced to a new skill) or chapter 3 (when the two-skill intervention programs began to teach the second skill); for other chapters in which reviewing was the main focus, participants tended to spend less time, between 10 and 20 min (Extended Data Table 6).

Across interventions, between 51% and 84% of participants (average 63%) completed all the intervention programs for the acute phase intervention. Between 74% and 93% of the participants for each intervention arm (average 78%) completed at least up to chapter 4 of the program covering all the major contents for the interventions (Extended Data Table 7).

The proportions of participants completing the assessments were 95.3% (3,751 of 3,936) at week 3 and 97.2% (3,824 of 3,936) at week 6 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 5). In total, 2.8% of participants (107 of 3,824) confirmed that they had sought mental health care from a professional (psychiatrist or psychologist) by the week 6 follow-up.

Safety

As of the close date for the acute phase intervention (19 April 2024), we observed 225 warnings of increased depression and suicidality as indicated by PHQ-9 scores of ≥10 and an item 9 (suicidality) score of ≥2, of which 53 warnings happened on two consecutive occasions for 39 users (1% of 3,936 participants). No serious adverse events have been reported. These adverse events were too infrequent to allow meaningful comparisons among arms.

Sensitivity analyses

Supplementary Tables 6–9 show the results of all the prespecified sensitivity analyses subgrouping participants by baseline ISI scores to see whether the scores moderated the primary outcome of the PHQ-9, or limiting participants to those with elevated baseline scores for each secondary outcome to mitigate floor and/or ceiling effects. All the sensitivity analyses corroborated the main findings regarding the primary and secondary outcomes.

Post hoc analyses

We added two post hoc analyses to facilitate interpretation of the primary analysis results, first by extending the follow-up and second by component analysis of CBT skills.

We followed up the cohort to week 26. Participants continued to have free access to the app but, after week 6, and especially after week 10 when most of the participants had completed the program, they accessed the app for only 1–4 min per month on average (Extended Data Table 6). By week 30, the rate of adherence to the interventions increased to an average of 79% (range: 66–92%) for the whole program and 84% (range: 73–94%) for the main parts of the program (Extended Data Table 7). Supplementary Table 10a,b shows the results of analyses of the main and interaction effects, and Extended Data Table 8 shows combined analysis of the PHQ-9 up to week 26. All the interventions maintained their superiority compared with the two controls at week 26, and the two-skill interventions were generally superior to single-skill interventions with an SMD of −0.08 (−0.16 to −0.00, P = 0.049). The health information and self-check were no longer differentiated as control conditions (Extended Data Fig. 2).

Supplementary Tables 11 and 12 show the component analyses at weeks 6 and 26 respectively, with or without interaction terms in the MMRM. Table 5 juxtaposes the results with interaction terms from the two timepoints. At week 6, nonspecific treatment effects were beneficial (reducing the total effect size by −0.18 (−0.32 to −0.04)), while the waiting list effect was harmful (increasing the total effect size by 0.17 (0.03 to 0.31)). Specific efficacies of individual cognitive or behavioral skills were evident, while their interactions also tended to be influential. At week 26, however, the nonspecific effects were diminished (0.08, 95% CI: −0.09 to 0.25), and interactions among the skills also grew weaker. The specific effects of individual cognitive or behavioral skills tended to increase in size.

Discussion

We developed a self-help smartphone CBT app involving five representative cognitive or behavioral skills (BA, CR, PS, AT and BI) and conducted an individually randomized controlled trial of these interventions for subthreshold depression26,27. We achieved a follow-up rate of 97% at week 6 and the average completion rate for the program was 84%. All skills and their combinations were differentially superior to the delayed treatment, health information and self-check controls, with effect sizes ranging between 0.67 and 0.16 for the primary outcome of depression at week 6. These interventions were also differentially efficacious for the secondary outcomes of anxiety, insomnia and wellbeing. The efficacy of cognitive and behavioral interventions was maintained up to week 26.

In a previous component network meta-analysis of iCBT, we found that BA was the most efficacious component; there was some suggestive evidence supporting BI, PS and AT, but no strong support for CR17. The results of the current study are aligned with these estimates because the 95% CIs of the effect sizes of the components in our study overlapped with those from the meta-analysis. However, our study demonstrated specific efficacies of individual cognitive or behavioral skills directly in a single randomized trial and yielded more precise effect estimates for these components because of its large sample size, fixed intervention components and master protocol design. Moreover, we were able to demonstrate the efficacy of CR per se, in contrast to the meta-analysis.

We prioritized BA in the design of the four 2 × 2 factorial trials because previous studies have shown it to be among the more efficacious of the skills17 and therefore a good candidate for inclusion in future iCBT packages16 or even as a standalone intervention28. As expected, BA was among the more efficacious skills at week 6 (Table 4), but seemed to lose its edge at week 26 (Extended Data Table 8). There was greater adherence to BA than to the other skills, except for BI (Extended Data Table 7). However, combining BA with another skill did not result in a straightforward sum of the single-skill intervention arms at week 6. In retrospect, this was to be expected because all intervention arms must have had some common nonspecific treatment effects due to the placebo effect, self-monitoring and encouragement emails. Intervention arms teaching two skills could not double these effects and therefore were not a simple sum of the efficacies of single-skill interventions. This was evident in analyses of the interaction terms of factorial trials (Table 3) and was corroborated by the component analyses at week 6 (Table 5). When we followed up the cohort to week 26, however, there were no longer demonstrable nonspecific treatment effects and interactions among the skills became less influential. Individual skills maintained their effect sizes. In other words, learning skills continued to be beneficial up to week 26, and learning two skills was more beneficial than learning one.

The five cognitive or behavioral skills were also differentially efficacious for the secondary outcomes of anxiety, insomnia and mental wellbeing. The intervention arms BA, BI and probably to a lesser degree BA + CR or BA + PS were particularly efficacious in reducing anxiety symptoms. As expected, BI and BA + BI had the largest effect sizes in improving sleep. For positive mental wellbeing, BA, BI and BA + AT were more promotional than the delayed treatment or self-check controls. Although all the cognitive or behavioral skills we included in the app were beneficial overall, these differentiations provide the first step in matching interventions with the status and needs of individual participants. A future study should also take into account participants’ other characteristics to personalize and optimize the interventions.

We were able to monitor participant access to the program through the remote server. The access logs indicated that the participants’ app usage occurred in short, intermittent sessions, typically lasting between 2 and 10 min. This suggests that participants engaged with the app during brief moments of free time throughout their day.

The amount of time spent accessing the app dramatically decreased after week 6 or week 10, by which time most participants had finished all of the lessons in their allocated intervention. However, the efficacies of the CBT skills persisted over the 26 weeks of follow-up. We interpret this as a sign of true learning: once users master the essentials of BA, CR or any other CBT skill, they do not need to go back to the app but can practice them on their own and continue to benefit from the learned skills.

The rate of adherence to the program, defined as completing the main learning materials for the interventions, reached 78% by week 10 and 84% by week 30, on average. These figures compare favorably with those reported in the literature for similarly defined adherence rates of iCBT programs, which are 30% for unguided iCBT29 or 68% for therapist-guided iCBT30. Throughout the acute intervention and follow-up, PS, CR, BA + PS and BA + CR tended to have lower adherence rates than the other intervention arms. However, although PS tended to show smaller effect sizes, BA + PS and BA + CR were usually associated with the largest effect sizes among all the interventions.

Our results provide insights into control conditions in psychotherapy trials22. There have been several network meta-analyses suggesting that waiting list controls may be harmful and produce larger effect size estimates than no treatment for the same intervention23,31. However, the comparisons were mostly indirect because few studies directly compared the waiting list against no treatment. The current study provides evidence that the waiting list is inferior to other commonly used control conditions in psychotherapy trials. The health information arm in our study, without weekly self-checks or encouragement emails from the central office, represents an ‘informed, health-conscious life as usual’ and may be considered the most appropriate control when the research question of the study is to ask whether it is meaningful to do something more than this informed life as usual. The self-check arm included repeated administration of the PHQ-9 and weekly encouragement email from the office; although none of these constitute specifically cognitive or behavioral interventions, they are integral parts of any guided CBT intervention and comparison with them is meaningful only when we are interested in the specific efficacies of particular intervention components (as in our component analyses). However, the self-check control would be inappropriate if the relevant study question was the efficacy of the total program including specific as well as nonspecific, but essential, ingredients of CBT. Although the self-check was the strongest control for the PHQ-9, this was not the case for the other outcomes, for which the health information was strongest. In other words, repeating self-reports may improve scores on the self-report scale, but not on others. In comparison with these, the waiting list overestimates the efficacy of the intervention by SMDs of −0.35 (−0.50 to −0.21) or −0.18 (−0.33 to −0.04) respectively, and should not be used in confirmatory trials of interventions (late phase 2 or phase 3 studies). Its use may be justifiable in exploratory early phase 2 or pragmatic phase 4 studies but in such instances interpretation of the obtained effect sizes must be nuanced accordingly. A corollary to this is that no future meta-analysis of psychotherapies should combine these different control conditions, otherwise the resultant pooled effect estimate of a therapy would be uninterpretable.

Our results contrast with the so-called Dodo bird verdict, which claims that all bona fide psychotherapies have comparable efficacies32. If this claim held true for iCBT, we should expect: (1) all skills to be equally effective for depression, anxiety, insomnia and wellbeing; and (2) one-skill interventions to match two-skill interventions in efficacy. However, we found that different cognitive or behavioral skills had varying efficacy for depression and other symptoms. Although the benefits were not additive at week 6, by week 26, learning two skills proved more efficacious than learning one skill. The inability to differentiate between psychotherapies in past research is probably due to the fact that different skills were combined in various ways and in variable quality, and also to the small sample sizes in dismantling studies (typically only ten per arm)33. Mixing various control conditions may have further diluted the differences. Our study used standardized and well-controlled interventions to provide support for differential efficacies among the five cognitive or behavioral skills, distinct from nonspecific common effects or the nocebo effect due to the waiting list condition. Given the results from several component network meta-analyses distinguishing helpful, neutral or even harmful elements in interventions traditionally classified under one name (for example, CBT for panic disorder34, iCBT for depression17 and CBT for insomnia35), more rigorous and granular research on the Dodo bird verdict is warranted.

Psychotherapies are complex interventions and are intrinsically multifarious. Allegedly new interventions appear every year but their efficacies per se, let alone their relative efficacies against older therapies, often remain elusive. When multiple interventions and control conditions are available, the master protocol design allows for the comparison of several interventions against common controls and the platform trial allows for the entry of new interventions (and the dropping of old, inefficacious ones)20,21. Our RESiLIENT trial is one of the earlier adoptions of this advanced trial methodology in the field of psychotherapy19,20. It must be pointed out that the master randomized trial not only enables efficient use of the sample size by sharing common controls, but also saves time, effort and money on the part of researchers because multiple hypotheses can be tested on the same platform, obviating the costs of starting and closing individual trials. When a new arm is added to an existing platform, recruitment can start at full speed.

This study is not without limitations. First, given the nature of the interventions, it was not possible to keep participants blind to the intervention, as is the case with all psychotherapy trials. This could lead to performance bias. However, in the RESiLIENT trial there were 12 arms and the nature of each arm—whether it was intended as an active intervention or a control and comparison intervention—was not emphasized to participants (except for the delayed treatment where it was obvious that the active intervention was withheld to week 6). Thus participants experienced the nine intervention arms as well as the weekly self-check arm and the health information arm as if they were receiving intervention outside the trial setting. There was no apparent deviation in the interventions because of the trial setting, which should therefore not constitute a risk of bias due to deviations from intended interventions as per the new Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool36. In addition, the lack of participant blinding could also be associated with assessment bias, because all outcomes in this study were self-rated by participants. However, there is growing empirical evidence to show that self-ratings tend to lead to more conservative effect size estimates than blinded observer ratings in clinical trials37,38,39,40. Second, this study focused on the acute intervention effects and examined their durability up to 26 weeks. Longer follow-up and an examination of the enduring effects of the skills are warranted. Third, we examined five representative cognitive or behavioral skills but did not include relaxation, mindfulness or acceptance, among others, which sometimes are considered effective elements in broadly conceived CBT41. We limited ourselves to CBT skills based on classical behavioral or cognitive techniques that had some empirical support17, but did not include relaxation because there is evidence suggestive of its harmful effects17,34,35. We did not include third-wave components such as mindfulness or acceptance because theoretically they are posited to be antithetical to CR and might present some interpretational difficulties when combined with the selected skills. We need comparative and combinational studies for these and other new interventions before we can be certain of their inclusion in empirically proven psychotherapy arsenals. Fourth, as we accumulate knowledge about effective ingredients of psychotherapies, they may or may not be additive if they are provided altogether. In this study, two-skill interventions including the BA were not additive at week 6, but were largely so at week 26 (except for BA and BI). Ultimately, this is another empirical question for future studies. Lastly, it is unclear whether our findings about the five skills are limited to our smartphone app only for adults with subthreshold depression and may not be generalizable to CBT skills administered using other apps or by human therapists; extrapolate to the school setting, to elderly people or to people with comorbidities; apply to populations other than Japanese; or extrapolate to major depressive disorder. These are all empirical questions that require further research.

In conclusion, CBT skills as implemented in our smartphone app proved differentially efficacious against depressive symptoms for up to 26 weeks in adults with subthreshold depression. Differential efficacies will enable efficient packaging of skills that match individual participant’s characteristics and needs by providing an evidence base to decide which skills to prioritize. Careful attention must be given to the combinations of skills in the package to address potential interactions. Given the substantial and persistent global burden of depression, the widespread implementation of a scalable service platform based on this app to promote mental health among people with subthreshold depression is both timely and crucial. Leveraging smartphone technology and remote server connectivity offers a promising avenue for the continued improvement of digital interventions.

Methods

The RESiLIENT trial is a master protocol trial involving four 2 × 2 factorial trials. The study was approved by Kyoto University Ethics Committee (C1556) on 3 March 2022. Recruitment of participants took place between 5 September 2022 and 21 February 2024. We preregistered the trial in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000047124) on 1 August 2022. We have previously published the study protocol18. We published the SAP24 on 18 March 2024 after the last-participant-in but before the last-participant-out. The protocol and SAP are available in the Supplementary Information and are summarized here. This report follows the CONSORT 2010 statement42 and its extensions for nonpharmacologic treatments43 and for factorial randomized trials44.

The study protocol is available as an open-access publication18 and the SAP is available on MedRxiv24; both are given in the Supplementary Information.

Participants

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) people of any gender, aged 18 years or older at the time of providing informed consent; (2) in possession of their own smartphone (either iOS or Android); (3) written informed consent for participation in the trial; (4) completion of all the baseline questionnaires within 1 week after providing informed consent; (5) screening PHQ-945 total scores of (a) between 5 and 9, inclusive, or (b) between 10 and 14, inclusive, but not scoring 2 or 3 on its item 9 (suicidality). Exclusion criteria were: (1) cannot read or write Japanese; and (2) receiving treatment from mental health professionals at the time of screening.

Study setting

Participants were recruited across Japan from: (1) health insurance societies. There are several types of public health insurance scheme together constituting universal healthcare in Japan. We collaborated with two large associations, the National Federation of Health Insurance Societies covering employees and their families in large corporations (~30 million insured) and the Japan Health Insurance Association covering employees of small- to middle-sized corporations and their families (~35 million insured); (2) business companies and corporations; (3) community and local governments; and (4) direct-to-consumer advertisements.

Procedures, randomization and masking

We asked interested, potential participants to log onto a website specifically prepared for the trial and fill in the screening questionnaire. Once we had ascertained the minimum eligibility criteria (age, possession of smartphone, not receiving treatment from mental health professionals), we invited them to attend the online informed consent session on Zoom in which we explained all the details of the study and its procedures. Once individuals had agreed and signed their digital consent forms, we allowed them access to the app downloaded from the App Store or Google Play by using an ID and password. Consenting individuals then had to complete all the baseline questionnaires within 1 week. After they had completed all the questionnaires, the app automatically randomly allocated participants to 1 of the 12 intervention or control arms according to their employment status (yes versus no) using the preinstalled permuted block randomization sequence, prepared by an independent statistician. The block size was known only to the statistician and allocation was concealed from any study personnel involved in participant recruitment.

Given the nature of the intervention and the study procedure, neither the participants nor the trial management team were blinded to the intervention. All the assessments in this study were completed by the participants on the app.

The participants were remunerated with 1,000 yen for completing the week 3 questionnaires, 2,000 yen at week 6, 1,000 yen at week 26 and 2,000 yen at week 50.

Interventions and controls

Nine intervention arms and one of the three control arms were combined to form the four 2 × 2 factorial trials, as shown in Fig. 1. The participants were randomized equally to one of the nine intervention arms or three control arms.

Interventions

The intervention arms were: BA, CR, PS, AT, BI, BA + CR, BA + PS, BA + AT and BA + BI. BA consists of psychoeducation about pleasurable activities according to the ‘outside-in’ principle. It provides a worksheet for a personal experiment to test out a new activity and also a gamified ‘action marathon’ to promote such personal experiments. CR consists of psychoeducation using the cognitive behavioral model and CR. The participant learns how to monitor their reactions to situations in terms of feelings, thoughts, body reactions and behaviors by filling in mind maps, which the participant then uses to apply CR and find alternative thoughts. PS teaches participants how to break down the issue at hand, to specify a concrete and achievable objective for the issue, to brainstorm possible solutions and compare their advantages and disadvantages, and finally to choose the most desirable action and act on it. A worksheet to guide participants through this process is provided. AT consists of psychoeducation of assertive communication in contrast to aggressive or passive communication. The participant learns how to express their true feelings and wishes without hurting others or sacrificing themselves. They complete worksheets to construct appropriate lines in response to their own real-life interactions. BI teaches the mechanisms of healthy sleep, invites the participant to keep daily sleep records, based on which the participant can start to apply sleep restriction and stimulus control techniques.

Controls

In psychotherapy trials, there is no gold standard control condition such as the pill placebo in pharmacotherapy trials22. Psychotherapy controls must be designed in accordance with the clinical questions of the study as well as the participants’ needs and the available resources, and may produce different effect size estimates23. In the RESiLIENT trial, we therefore used three different control conditions with different levels of stringency: (1) weekly self-checks, (2) health information and (3) delayed treatment.

In the weekly self-check arm, participants received weekly encouragement emails and monitored their moods via weekly PHQ-9 measurements up to week 6 (as in the intervention arms) and then monthly PHQ-9 measurements thereafter up to week 50. This arm is intended as an attention control to match the attention provided through encouragement emails and self-checks but lacking in active ingredients.

In the health information arm, participants received the URLs of websites containing tips for a healthy life (physical activities, nutrition and oral health, none of which focused on mental health) for the initial 3 weeks and then were asked to answer quizzes to test comprehension. Participants were asked to complete self-reports at weeks 3 and 6 (without encouragement emails), and then follow-up evaluations thereafter up to week 50. This arm is intended to emulate a placebo intervention.

In the delayed treatment arm, the participants were placed on the wait list and asked to complete self-reports at weeks 3 and 6. They were then randomized to 1 of the 11 arms (1 to 11) at week 6, if they so wished, and completed the respective programs thereafter.

Resilience Training app

All the interventions and controls were provided on the Resilience Training app v.2.1. Each intervention module consisted of seven chapters, each divided into two to five lessons as appropriate. Extended Data Fig. 1a shows how chapters and lessons were combined in each of the 12 intervention and control arms.

Extended Data Fig. 1b provides screenshots from the smartphone app. Each chapter provided explanations of the skill to be learned as well as a worksheet to practice the learned skill. Participants were expected to complete one chapter per week and could only move on to the next chapter one week after they started the previous chapter and having completed one worksheet.

In addition participants received weekly encouragement emails (except in the health information and delayed treatment arms), which were templated but tailored in accordance with each participant’s progress by the trial coordinators in the management team. Participants were prompted to complete the PHQ-9 every week on the app. All the coordinators were forbidden from providing any therapeutic contents.

2 × 2 factorial trials

In the factorial design, we prioritized BA because it has been shown to be as good as full-package CBT28, was the most effective skill in the component network meta-analysis of iCBT17 and has increasingly been used in iCBT interventions aiming at scalability as BA alone or in combination of BA plus PS16. We used delayed treatment as the control arm in the primary analyses but replaced it with the health information and self-check arms in the sensitivity analyses (‘Statistical analyses’ below).

Concomitant interventions

All participants in the active and control arms were free to seek whatever mental health interventions they wished over the 26 weeks. We recorded the received professional interventions, either pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy at week 6.

Safety monitoring

All serious adverse events were handled according to standard operationalized procedure 10 by the Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine (http://www.ec.med.kyoto-u.ac.jp/doc/SOP10.pdf). In addition, when any increase in suicidality (defined as a score of 10 or more on the total PHQ-9 and 2 or more on item 9 of PHQ-9 for two consecutive weeks) was noted, an email was sent to the participant recommending that they visit the consultation services listed by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare for the general public (https://kokoro.mhlw.go.jp/agency/) or other mental health professionals.

Baseline measurements

Demographic, psychosocial and clinical variables were measured at baseline as detailed below. Details of each scale are given in the protocol (Supplementary Information). All measurements were collected on the Resilience Training app.

The measured demographic variables were: (1) age; (2) gender; (3) marital status; (4) number of cohabitants; (5) Area Deprivation Index (as estimated by the zip code in 2020)46; (6) education; (7) employment; (8) physical conditions and illnesses, including past and current treatments; (9) physical disability; (10) mental health conditions, including past and current treatments; (11) alcohol use; and (12) the CAGE questionnaire47,48.

The following psychosocial scales were used: (1) the short form of the Big-5 questionnaire49,50,51; (2) Adverse Childhood Experiences52,53; (3) Assessment of Signal Cases (ASC)–Life difficulties54; (4) ASC–Social support54; (5) CBT Skills Scale55; and (6) Readiness for smartphone CBT, (a) ASC–Motivation54 and (b) familiarity with smartphone use.

Clinical variables were measured using: (1) PHQ-956, (2) GAD-757, (3) ISI58, (4) past and current major depressive episodes according to the major depression section of the computerized WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview59,60, (5) Work and Social Adjustment Scale61, (6) Health and Work Performance Questionnaire62,63, (7) Utrecht Work Engagement Scale64, (8) EuroQOL-5D-5L65,66, (9) SWEMWBS67,68, (10) CSQ-369, (11) adherence to smartphone CBT and (12) safety information.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is the change in PHQ-9 score from baseline to week 6.

Secondary outcome

The secondary outcomes include: (1) changes in PHQ-9 from baseline to weeks 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5; (2) changes in the GAD-757 from baseline to weeks 3 and 6; (3) changes in the ISI70 from baseline to weeks 3 and 6; (4) changes in the SWEMWBS68 from baseline to weeks 3 and 6; (5) adherence to the smartphone CBT; and (6) safety.

Anxiety usually coexists with depression and we aimed to examine what effects the intervention components, although mainly targeting depression, may have on anxiety. We aimed to monitor the broad psychopathology of common mental disorders encompassing depression, anxiety and insomnia as well as positive mental health which deteriorates in common mental disorders.

Sample size

The RESiLIENT trial was powered for each factorial trial for its primary outcome, that is, PHQ-9 at week 6. The Fun to Learn, Act and Think through Technology trial showed an SMD of 0.3–0.4 for an earlier version of the Resilience Training app using the combination of BA + CR over the waiting list control among patients with drug-refractory depression71. To detect an SMD of 0.2 at alpha = 0.05 and beta = 0.10, each factorial trial in the current master protocol would need 1,053 participants in total (FactorialPowerPlan, http://methodology.psu.edu), hence 264 in each arm. Altogether the RESiLIENT trial will require 264 × 12 = 3,168 participants with baseline PHQ-9 scores of 5 or more. The Healthy Campus Trial, which used an earlier version of the Resilience Training app among university students, had 5% dropout rates for its eighth week outcome25. We expected somewhat higher dropout rates in the RESiLIENT trial, which targets the general adult population in the community. Assuming a 10% dropout rate, the required sample size was 3,520.

Statistical analyses

We conducted all the analyses with R (v.4.3.1), and used the packages mmrm (v.0.3.11)72 and emmeans (v.1.9.0)73.

Efficacy analyses of the primary outcome

Primary efficacy analyses

In the preplanned primary analysis, each of the four 2 × 2 factorial trials was analyzed independently in accordance with the master protocol design framework. The four trials used the BA arm (intervention arm 1) and the control arm (intervention arm 12, delayed treatment) in common. Intervention arms 11 (health information) and 10 (self-check), with increasing stringency as the control, were used in sensitivity analyses; that is, we performed additional analyses changing the control arm to arm 11 or 10 respectively. For the fourth trial involving BA and BI, participants who worked in three shifts were excluded because shift workers cannot be expected to make optimal use of BI.

We used the MMRM74,75 to estimate the mean difference in change scores on the PHQ-9 for each component while adjusting for missing outcomes. The model included fixed effects of treatment, visit (as categorical) and treatment-by-visit interactions, adjusted for baseline PHQ-9 scores, employment status, age and gender. Each of the experimental factors was coded at two levels (presence was coded as 1 and absence was coded as 0). The covariance matrix structure of outcome variables was set to unstructured. The standard error estimates and degrees of freedom were adjusted using the Kenward–Roger method76,77. We also estimated least squares mean change scores for the PHQ-9 at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 based on the estimated models of the MMRM analysis. For the effect of BA, which was estimated in all four 2 × 2 trials, we presented the effect size estimate of the first trial (the 2 × 2 trial involving BA and CR) as the primary result because BA and CR are the most typical ingredients across broadly conceived CBT interventions.

We applied no adjustment for multiple testing in examination of statistical significance of the main effects and the conventional threshold for statistical significance (P < 0.05, two-sided), because the multiple hypotheses have been tested independently in these trial designs assuming as if the tested interventions could have been assessed in separate trials78,79. We performed another MMRM analysis involving a two-way interaction term of each two components to assess the interaction between the treatments as a sensitivity analysis. Previous research has not been suggestive of interactions among iCBT components17,25, but when we identified a strong interaction, we interpreted the results considering the interaction.

Effect sizes (SMDs) were calculated using the observed baseline SD for within-group change scores and the observed week 6 SD for group differences.

Secondary efficacy analyses

To assess the comparative efficacy of the five CBT skills and their combinations, we additionally performed a combined analysis via pooling the four factorial trials along with all the control arms. For this we performed the MMRM analysis for the pooled dataset and provided comparative effect size information for all the CBT skills and their combinations evaluated in the four trials. In this analysis we included all the three control conditions and compared comprehensively. In this combined analysis, we included shift workers, although such inclusion may lead to underestimating the effect of BI on depression, to maintain the statistical power for the analysis and make the results as comparable as possible to those in the primary 2 × 2 trial analyses.

Efficacy analyses for secondary outcomes

We performed MMRM analyses for the repeated measurement outcomes of GAD-7, ISI and SWEMWBS until week 6. We used the same modeling strategy with the analysis of the primary outcome.

Sensitivity analyses

We evaluated the robustness of the foregoing analyses by conducting the following prespecified sensitivity analyses.

For the 2 × 2 trials:

-

(1)

We examined interactions among the skills as a sensitivity analysis. In examining interactions among components, we also performed linear regression analyses using only the week 6 data for each of the 2 × 2 trials.

-

(2)

We used control arm 10 (self-check) or 11 (health information) instead of 12 (delayed treatment) in each of the 2 × 2 trials.

-

(3)

For the factorial trial examining BA and BI, we subgrouped participants into those who scored ≥8 versus those who scored ≤7 on the ISI at baseline. Here, the primary outcome was the PHQ-9, and this subgroup analysis confirmed whether the effect of BI is similar regardless of the baseline insomnia severity.

For the secondary outcomes:

-

(4)

For the secondary outcome of the GAD-7, we limited participants to those who scored ≥5 on the GAD-7 at baseline (that is, those who presented with at least some anxiety symptoms at baseline). This mitigated the floor effect on the GAD-7.

-

(5)

For the secondary outcome of the ISI, we limited participants to those who scored ≥8 on the ISI at baseline (that is, those who presented with at least some insomnia symptoms at baseline). This mitigated the floor effect on the ISI.

-

(6)

For the secondary outcome of the SWEMWBS in the four 2 × 2 factorial trials, we limited participants to those who scored ≤20 on the SWEMWBS at baseline (that is, those who showed reduced wellbeing at baseline). This mitigated the ceiling effect on the SWEMWBS.

Adherence

We used two definitions of adherence to the program in accordance with the previous literature: completion of the whole program and completion of the main parts of the program29,30. In this study, we operationally defined the former as completing all seven chapters (the introduction, chapters 1 to 5 and the epilogue) and the required worksheets, and the latter as finishing at least up to chapter 4 and the associated worksheets because the Introduction and the first four chapters cover the main learning materials to be taught in each arm, whereas chapter 5 and the epilogue are only review materials (Extended Data Fig. 1a). We set the deadline for the acute phase intervention at week 10 and that for the follow-up at week 30 to allow participants some additional time beyond the program schedule to complete any missed lessons or tasks.

Safety analyses

We descriptively reported potential adverse reactions and serious adverse events during the 6-week intervention via user self-reports.

Lived experience involvement

We revised the texts and the user interface of the app in collaboration with a group of people with lived experiences. However, they were not involved in the trial design, data analyses or interpretations of the current study findings.

Changes from the protocol or the SAP

The published protocol (Supporting Information) declared that we had two analyses planned for the RESiLIENT trial, focusing on the change in PHQ-9 from baseline to week 6 (analysis 1) and the incidence of a major depressive episode by week 50 (analysis 2). This paper is a report for analysis 1, and we prespecified the SAP accordingly before the relevant data became available (Supplementary Information). We will report analysis 2 and the outcomes listed as secondary in the published protocol, but not covered in the current SAP, in future papers. We plan to publish a SAP for the latter analyses before the data for the one-year outcomes become available.

In this study, we followed the analyses as prespecified in the SAP for analysis 1 (Supplementary Information) but added two post hoc analyses to inform and facilitate interpretations of the primary analysis results.

First, we extended the MMRM analyses of the primary outcome (PHQ-9) up to week 26 to test the durability of the effects we had confirmed immediately after the interventions at week 6. The statistical power for these additional analyses remained adequate for an SMD of 0.2 at alpha = 0.05 and beta = 0.10 assuming a 10% dropout rate, as originally required for the week 6 primary analyses of the 2 × 2 factorial trials.

Second, we applied the analytical methods of component analyses to the week 6 and week 26 outcomes to more finely differentiate the specific efficacies of individual CBT skills in addition to the nonspecific treatment effects and the waiting list effect based on the MMRM model. In this model, we considered the health information control, in which participants read information on physical, nutritional and oral health on the app, but received no encouragement emails and did not fill in the PHQ-9 on a weekly basis, as the reference. In comparison with this, the delayed treatment control was considered to have the waiting list component wl17,23,35. All the intervention arms were assumed to include a nonspecific treatment component ns, which included the placebo effect, human contact via encouragement emails and weekly self-checks17,35, in addition to their specific skill effects.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Deidentified individual participant data and data dictionary will be made available 24 months after publication on UMIN-ICDR, an individual case data repository managed by the Japanese University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Center (https://www.umin.ac.jp/icdr/index.html). Proposals with specific aims and an analysis plan should be directed to the corresponding author, T.A.F. (furukawa@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp). The decision will be made within a month.

Code availability

R code files used in the statistical analyses are available on GitHub at https://github.com/nomahi/RESiLIENT.

References

Zhang, R. et al. The prevalence and risk of developing major depression among individuals with subthreshold depression in the general population. Psychol. Med. 53, 3611–3620 (2023).

Jinnin, R. et al. Detailed course of depressive symptoms and risk for developing depression in late adolescents with subthreshold depression: cohort study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 13, 25–33 (2017).

Sigstrom, R., Waern, M., Gudmundsson, P., Skoog, I. & Ostling, S. Depressive spectrum states in a population-based cohort of 70-year olds followed over 9 years. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 33, 1028–1037 (2018).

Karsten, J., Penninx, B. W., Verboom, C. E., Nolen, W. A. & Hartman, C. A. Course and risk factors of functional impairment in subthreshold depression and anxiety. Depress. Anxiety 30, 386–394 (2013).

Backenstrass, M. et al. A comparative study of nonspecific depressive symptoms and minor depression regarding functional impairment and associated characteristics in primary care. Compr. Psychiatry 47, 35–41 (2006).

Goldney, R. D., Fisher, L. J., Dal Grande, E. & Taylor, A. W. Subsyndromal depression: prevalence, use of health services and quality of life in an Australian population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 39, 293–298 (2004).

Cuijpers, P. et al. Differential mortality rates in major and subthreshold depression: meta-analysis of studies that measured both. Br. J. Psychiatry 202, 22–27 (2013).

Cuijpers, P. et al. Economic costs of minor depression: a population-based study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 115, 229–236 (2007).

Lee, Y. Y. et al. The risk of developing major depression among individuals with subthreshold depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Psychol. Med. 49, 92–102 (2019).

Cuijpers, P. et al. Psychotherapy for subclinical depression: meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 205, 268–274 (2014).

Buntrock, C. et al. Psychological interventions to prevent the onset of major depression in adults: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 11, 990–1001 (2024).

Harrer, M. et al. Psychological intervention in individuals with subthreshold depression: individual participant data meta-analysis of treatment effects and moderators. Br. J. Psychiatry (in press).

Simon, G. E., Moise, N. & Mohr, D. C. Management of depression in adults: a review. JAMA 332, 141–152 (2024).

Herrman, H. et al. Time for united action on depression: a Lancet–World Psychiatric Association Commission. Lancet 399, 957–1022 (2022).

Cuijpers, P., Noma, H., Karyotaki, E., Cipriani, A. & Furukawa, T. A. Effectiveness and acceptability of cognitive behavior therapy delivery formats in adults with depression: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 76, 700–707 (2019).

Karyotaki, E. et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: a systematic review and individual patient data network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 361–371 (2021).

Furukawa, T. A. et al. Dismantling, optimising, and personalising internet cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis using individual participant data. Lancet Psychiatry 8, 500–511 (2021).

Furukawa, T. A. et al. Four 2 × 2 factorial trials of smartphone CBT to reduce subthreshold depression and to prevent new depressive episodes among adults in the community-RESiLIENT trial (Resilience Enhancement with Smartphone in LIving ENvironmenTs): a master protocol. BMJ Open 13, e067850 (2023).

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Master Protocols for Drugs and Biological Product Development: Guidance for Industry (Draft Guidance) (2023); https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/master-protocols-drug-and-biological-product-development

Gold, S. M. et al. Transforming the evidence landscape in mental health with platform trials. Nat. Mental Health https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-025-00391-w (2025).

Park, J. J. H. et al. An overview of platform trials with a checklist for clinical readers. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 125, 1–8 (2020).

Gold, S. M. et al. Control conditions for randomised trials of behavioural interventions in psychiatry: a decision framework. Lancet Psychiatry 4, 725–732 (2017).

Michopoulos, I. et al. Different control conditions can produce different effect estimates in psychotherapy trials for depression. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 132, 59–70 (2021).

Noma, H. et al. RESiLIENT (Resilience Enhancement with Smartphone in LIving ENvironmenTs) Trial: The Statistical Analysis Plan. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.16.24304261 (2024).

Sakata, M. et al. Components of smartphone cognitive-behavioural therapy for subthreshold depression among 1093 university students: a factorial trial. Evid. Based Ment. Health 25, e18–e25 (2022).

METAPSY. Meta-Analytic Database of Psychotherapy Trials (2024); https://www.metapsy.org/

Cuijpers, P., Harrer, M., Miguel, C., Ciharova, M. & Karyotaki, E. Five decades of research on psychological treatments of depression: A historical and meta-analytic overview. Am. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001250 (2023).

Cuijpers, P. et al. Psychotherapies for depression: a network meta-analysis covering efficacy, acceptability and long-term outcomes of all main treatment types. World Psychiatry 20, 283–293 (2021).

Karyotaki, E. et al. Predictors of treatment dropout in self-guided web-based interventions for depression: an ‘individual patient data’ meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 45, 2717–2726 (2015).

van Ballegooijen, W. et al. Adherence to internet-based and face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 9, e100674 (2014).

Furukawa, T. A. et al. Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: a contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 130, 181–192 (2014).

Wampold, B. E. et al. A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: empirically, ‘all must have prizes’. Psychol. Bull. 122, 203–215 (1997).

Cuijpers, P., Cristea, I. A., Karyotaki, E., Reijnders, M. & Hollon, S. D. Component studies of psychological treatments of adult depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychother. Res. 29, 15–29 (2019).

Pompoli, A. et al. Dismantling cognitive-behaviour therapy for panic disorder: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 48, 1945–1953 (2018).

Furukawa, Y. et al. Components and delivery formats of cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia in adults: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 81, 357–365 (2024).

Sterne, J. A. C. et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366, l4898 (2019).

Cuijpers, P., Li, J., Hofmann, S. G. & Andersson, G. Self-reported versus clinician-rated symptoms of depression as outcome measures in psychotherapy research on depression: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30, 768–778 (2010).

Sayer, N. et al. The relations between observer-rating and self-report of depressive symptomatology. Psychol. Assess. 5, 350–360 (1993).

Greenberg, R. P., Bornstein, R. F., Greenberg, M. D. & Fisher, S. A meta-analysis of antidepressant outcome under ‘blinder’ conditions. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 60, 664–669 (1992); discussion 670–667.

Miguel, C. et al. Self-reports vs clinician ratings of efficacies of psychotherapies for depression: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 34, e15 (2025).

Watkins, E., Newbold, A., Tester-Jones, M., Collins, L. M. & Mostazir, M. Investigation of active ingredients within internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: a randomized optimization trial. JAMA Psychiatry 80, 942–951 (2023).

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G. & Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340, c332 (2010).

Boutron, I. et al. CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann. Intern. Med. 167, 40–47 (2017).

Kahan, B. C. et al. Reporting of factorial randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA 330, 2106–2114 (2023).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K. & Williams, J. B. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 282, 1737–1744 (1999).

Nakaya, T. et al. Associations of all-cause mortality with census-based neighbourhood deprivation and population density in Japan: a multilevel survival analysis. PLoS ONE 9, e97802 (2014).

Fiellin, D. A., Reid, M. C. & O’Connor, P. G. Screening for alcohol problems in primary care: a systematic review. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 1977–1989 (2000).

Bush, B., Shaw, S., Cleary, P., Delbanco, T. L. & Aronson, M. D. Screening for alcohol abuse using the CAGE questionnaire. Am. J. Med. 82, 231–235 (1987).

Wada, S. Construction of the Big Five Scales of personality trait terms and concurrent validity with NPI [in Japanese]. Shinrigaku Kenkyu 67, 61–67 (1996).

Namikawa, T. et al. Development of a short form of the Japanese Big-Five Scale, and a test of its reliability and validity [in Japanese]. Shinrigaku Kenkyu 83, 91–99 (2012).

Toyomoto, R. et al. Validation of the Japanese Big Five Scale Short Form in a university student sample. Front. Psychol. 13, 862646 (2022).

Felitti, V. J. et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 14, 245–258 (1998).

Tsuboi, S. Creating a Japanese version Adverse Childhood Experiences score calculator [in Japanese]. in KAKENHI Reports (2014); https://kaken.nii.ac.jp/ja/report/KAKENHI-PROJECT-24790625/24790625seika/

Probst, T., Lambert, M. J., Dahlbender, R. W., Loew, T. H. & Tritt, K. Providing patient progress feedback and clinical support tools to therapists: is the therapeutic process of patients on-track to recovery enhanced in psychosomatic in-patient therapy under the conditions of routine practice? J. Psychosom. Res 76, 477–484 (2014).

Sakata, M. et al. Development and validation of the cognitive behavioural therapy skills scale among college students. Evid. Based Ment. Health 24, 70–76 (2021).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med 16, 606–613 (2001).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. & Lowe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092–1097 (2006).

Bastien, C. H., Vallières, A. & Morin, C. M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2, 297–307 (2001).

Peters, L. & Andrews, G. Procedural validity of the computerized version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI-Auto) in the anxiety disorders. Psychol. Med. 25, 1269–1280 (1995).

Shimoda, H., Inoue, A., Tsuno, K. & Kawakami, N. One-year test–retest reliability of a Japanese web-based version of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) for major depression in a working population. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 24, 204–212 (2015).

Mundt, J. C., Marks, I. M., Shear, M. K. & Greist, J. H. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br. J. Psychiatry 180, 461–464 (2002).

Kessler, R. C. et al. The World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). J. Occup. Environ. Med. 45, 156–174 (2003).

Kawakami, N. et al. Construct validity and test–retest reliability of the World Mental Health Japan version of the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire Short Version: a preliminary study. Ind. Health 58, 375–387 (2020).

Schaufeli, W. B., Shimazu, A., Hakanen, J., Salanova, M. & De Witte, H. An ultra-short measure for work engagement. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 35, 577–591 (2017).

Herdman, M. et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 20, 1727–1736 (2011).

Ikeda, S. et al. Developing a Japanese version of the EQ-5D-5L value set. J. Natl Inst. Public Health 64, 47–55 (2015).

Bartram, D. J., Sinclair, J. M. & Baldwin, D. S. Further validation of the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) in the UK veterinary profession: Rasch analysis. Qual. Life Res. 22, 379–391 (2013).

Shah, N., Cader, M., Andrews, B., McCabe, R. & Stewart-Brown, S. L. Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): performance in a clinical sample in relation to PHQ-9 and GAD-7. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 19, 260 (2021).

Attkisson, C. C. & Zwick, R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval. Program Plann. 5, 233–237 (1982).

Morin, C. M., Belleville, G., Bélanger, L. & Ivers, H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep 34, 601–608 (2011).

Mantani, A. et al. Smartphone cognitive behavioral therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for refractory depression: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 19, e373 (2017).

Sabanes Bove, D. et al. mmrm: Mixed Models for Repeated Measures (2024); https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.mmrm

Lenth, R. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means (2023); https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.emmeans

Mallinckrodt, C. H., Clark, W. S. & David, S. R. Accounting for dropout bias using mixed-effects models. J. Biopharm. Stat. 11, 9–21 (2001).

Mallinckrodt, C. H., Kaiser, C. J., Watkin, J. G., Molenberghs, G. & Carroll, R. J. The effect of correlation structure on treatment contrasts estimated from incomplete clinical trial data with likelihood-based repeated measures compared with last observation carried forward ANOVA. Clin. Trials 1, 477–489 (2004).

Kenward, M. G. & Roger, J. H. Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics 53, 983–997 (1997).

Kenward, M. G. & Roger, J. H. An improved approximation to the precision of fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 53, 2583–2595 (2009).

Balakrishnan, N. Methods and Applications of Statistics in Clinical Trials, Volume 1 and Volume 2: Concepts, Principles, Trials, and Designs (Wiley, 2014).

Fleiss, J. L. Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments (Wiley, 1999).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (grant no. JP21de0107005), awarded to T.A.F. (principal investigator), A.T., R.T., M.S., Y.L., M.H., T.A., N. Kawakami, T.N., N. Kondo and S.F. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.A.F. and M.H. conceived the study. T.A.F., J.M.S.W. and H.N. designed the study. Additional advice about design and statistical analysis was given by R.C.K., H.C. and P.C. Funding was obtained by T.A.F., M.H., T.A., N. Kawakami, T.N., N. Kondo, S.F. and H.N. T.A.F., M.H. and T.A. led the software development, with input from A.T., R.T., M.S. and Y.L. A.T., R.T., M.S. and Y.L. established the databases and managed the recruitment, data collection and processing, with help from N. Kawakami, T.N., N. Kondo and S.F. H.N. and T.A.F. undertook the statistical analyses, and had direct access to the full data. T.A.F. and H.N. wrote the first draft, and all the authors contributed to the interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript, and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

T.A.F. reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, DT Axis, Micron, Shionogi, SONY and UpToDate, and a grant from DT Axis and Shionogi, outside the submitted work. In addition, T.A.F. has a patent (7448125) and a pending patent (2022-082495), and has licensed intellectual properties for Kokoro-app to DT Axis. A.T. reports personal fees from Eisai and Shionogi outside the submitted work. M.S. is employed in the Department of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, which is an endowment department supported by the City of Nagoya, and has received a personal fee from SONY outside the submitted work. M.H. has a patent (7448125) and has licensed intellectual properties for Kokoro-app to Mitsubishi Tanabe. T.A. has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Chugai, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Kowa, Kyowa Kirin, Lundbeck, MSD, Meiji-Seika Pharma, Merck, Nipro, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shionogi, Sumitomo pharma, Takeda, Tsumura, UCB and Viatris, and a grant from Shinogi and royalties from Igaku-Shoin, outside the submitted work. T.A. serves as the representative director of the General Incorporated Association NCU CRESS and receives compensation as an advisor to Snom Inc. T.A. has pending patents (2020-135195 and 2024-516288) (Institute) and patents (7313617) (Institute). N. Kawakami is employed by the Junpukai Foundation and the Department of Digital Mental Health, The University of Tokyo, an endowment department that is supported by an unrestricted grant from 15 enterprises (https://dmh.m.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en). T.N. reports grants or contracts with I&H, Cocokarafine, Konica Minolta and NTT DATA, consulting fees from Ohtsuka, Takeda, Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca and Nippon Zoki, payment or honoraria for lectures, manuscript writing or educational events from Pfizer, MSD, Chugai, Takeda, Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Novartis, Allergan, Novo Nordisk, Toa Eiyo, AbbVie, Ono, GSK, Alexion, Cannon Medical Systems, Kowa, Araya, Merck and Amicus, stock options in BonBon Inc., and a donation from Cancerscan and JMDC, all outside the submitted work. S.F. received personal fees from Kyowa Kirin, Boehringer Ingelheim, Toray Medical, Health and Global Policy Institute, White Healthcare and Health Insurance for Start-up Companies, and research grants from the Japan Health Insurance Association, National Health Insurance Association for Civil Engineering and Construction, Osaka Prefecture and Cancerscan, outside this work. R.C.K. was a consultant for Cambridge Health Alliance, Canandaigua VA Medical Center, Child Mind Institute, Holmusk, Massachusetts General Hospital, Partners Healthcare, Inc., RallyPoint Networks, Inc., Sage Therapeutics and University of North Carolina. He has stock options in Cerebral Inc., Mirah, PYM (Prepare Your Mind), Roga Sciences and Verisense Health. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Thole Hoppen, Zhirong Yang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Ming Yang, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Contents of the interventions and controls.

The intervention arms #1 through #10 (BA through Self-check) filled in the PHQ-9 every week and received weekly encouragement emails from the clinical research coordinators at the central office. #11 (Health information) and #12 (Delayed treatment) were asked to fill in the PHQ-9 at weeks 3 and 6 only, and did not receive encouragement emails. AT: Assertion training, BA: Behavioural activation, BI: Behaviour therapy for insomnia CR: Cognitive restructuring, PS: Problem solving.

Extended Data Fig. 2 PHQ-9 change from baseline up to week 26.

Data represent least squares mean changes of the PHQ-9 scores estimated by the combined MMRM model. The regression model included fixed effects of treatment, visit (as categorical), and treatment-by-visit interactions, adjusted for baseline PHQ-9 scores employment status, age and gender. The error bars at weeks 6 and 26 represent SEMs. For more information, see Table 4, Extended Data Table 8, and Supplementary Table 2. AT: Assertion training, BA: Behavioural activation, BI: Behaviour therapy for insomnia, CR: Cognitive restructuring, PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PS: Problem solving.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary protocol, statistical analysis plan and Tables 1–12.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Furukawa, T.A., Tajika, A., Toyomoto, R. et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy skills via a smartphone app for subthreshold depression among adults in the community: the RESiLIENT randomized controlled trial. Nat Med 31, 1830–1839 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03639-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03639-1

This article is cited by

-

Associations of depression, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms in subthreshold depression: a network analysis

BMC Psychiatry (2025)

-

Trials for computational psychiatry

Nature Computational Science (2025)

-

Personalised & optimised therapy (POT) algorithm using five cognitive and behavioural skills for subthreshold depression

npj Digital Medicine (2025)