Abstract

The protocol of a randomized trial is the foundation for study planning, conduct, reporting and external review. However, trial protocols vary in their completeness and often do not address key elements of design and conduct. The SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) statement was first published in 2013 as guidance to improve the completeness of trial protocols. Periodic updates incorporating the latest evidence and best practices are needed to ensure that the guidance remains relevant to users. Here, we aimed to systematically update the SPIRIT recommendations for minimum items to address in the protocol of a randomized trial. We completed a scoping review and developed a project-specific database of empirical and theoretical evidence to generate a list of potential changes to the SPIRIT 2013 checklist. The list was enriched with recommendations provided by lead authors of existing SPIRIT/CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) extensions (Harms, Outcomes, Non-pharmacological Treatment) and other reporting guidelines (TIDieR). The potential modifications were rated in a three-round Delphi survey followed by a consensus meeting. Overall, 317 individuals participated in the Delphi consensus process and 30 experts attended the consensus meeting. The process led to the addition of two new protocol items, revision to five items, deletion/merger of five items, and integration of key items from other relevant reporting guidelines. Notable changes include a new open science section, additional emphasis on the assessment of harms and description of interventions and comparators, and a new item on how patients and the public will be involved in trial design, conduct and reporting. The updated SPIRIT 2025 statement consists of an evidence-based checklist of 34 minimum items to address in a trial protocol, along with a diagram illustrating the schedule of enrollment, interventions and assessments for trial participants. To facilitate implementation, we also developed an expanded version of the SPIRIT 2025 checklist and an accompanying explanation and elaboration document. Widespread endorsement and adherence to the updated SPIRIT 2025 statement have the potential to enhance the transparency and completeness of trial protocols for the benefit of investigators, trial participants, patients, funders, research ethics committees, journals, trial registries, policymakers, regulators and other reviewers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

“Readers should not have to infer what was probably done; they should be told explicitly.” Douglas G. Altman1

Robustly designed, properly conducted and fully reported randomized trials underpin evidence-based practice and policy. As the most important record of planned methods and conduct, a well-written protocol has a key role in promoting consistent and rigorous execution by the trial team. The protocol also serves as the basis for oversight and review of scientific, ethical, safety and operational issues by funders, regulators, research ethics committees/institutional review boards (REC/IRBs), journal editors, researchers, patients and the public2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. After trial completion, the protocol is essential for understanding and interpreting the results.

Despite the central role of protocols, there is substantial variation in the completeness of protocol content10,11. Many trial protocols do not adequately describe important elements, including the primary outcomes, treatment allocation methods, use of blinding, measurement of adverse events, sample size calculations, data analysis methods, dissemination policies, and roles of sponsors and investigators in trial design10,11,12. Gaps in protocol content can lead to avoidable protocol amendments13, inconsistent or poor trial conduct, and lack of transparency in terms of what was planned and implemented.

In response to these protocol deficiencies, the SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) guidance was first published in 2013 (refs. 14,15). Aligned with the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidance for reporting completed trials16, the international SPIRIT initiative aims to improve the completeness of trial protocols by producing evidence-based recommendations for a minimum set of items to be addressed in protocols. The SPIRIT 2013 guidance has been translated into seven languages and is widely endorsed by national funders, research organizations, over 150 medical journals and the World Association of Medical Editors.

In January 2020, the SPIRIT and CONSORT executive groups held a joint meeting in Oxford, UK, to discuss strategic planning. There was broad recognition of the need to update both checklists to reflect the evolving trials environment and methodological advancements, including the growing international support for improved research transparency, accessibility and reproducibility (collectively referred to as open science)17, as well as greater patient and public involvement in research.

As the SPIRIT 2013 and CONSORT 2010 statements were conceptually linked with overlapping content and implementation strategies, the two groups decided to merge into the joint SPIRIT–CONSORT executive group and to update both checklists simultaneously. The joint update was an opportunity to further align the checklists and provide consistent guidance in the reporting of trial design, conduct and analysis — from study conception to the publication of results. Harmonizing the reporting recommendations could help improve usability and adherence18. Here, we introduce the updated SPIRIT 2025 statement; the CONSORT 2025 statement is published separately16.

Methods

The methods have been detailed elsewhere19,20. In brief, we followed the EQUATOR Network guidance for developers of health research guidelines21. We first conducted a scoping review of the literature from 2013 to 2022 to identify published comments suggesting modifications or reflecting on the strengths and challenges of SPIRIT 2013; these findings have been published separately22. We also conducted a broader search for empirical and theoretical evidence published from 2013 to 2024 that was relevant to SPIRIT and risk of bias in randomized trials, producing the SPIRIT–CONSORT Evidence Bibliographic database23. The evidence identified in the literature was combined with recommendations provided by the lead authors of key SPIRIT and CONSORT extensions (Harms24, Outcomes25, Non-pharmacological Treatment26), and the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR)27, along with user feedback.

Based on the gathered evidence, a preliminary list of five potential additions to the SPIRIT 2013 checklist was created for review in an international, three-round online Delphi survey. A total of 317 participants were recruited through professional research networks, societies and the project website. Participants represented a broad range of roles in clinical trials, including statisticians/methodologists/epidemiologists (n = 198), trial investigators (n = 73), systematic reviewers/guideline developers (n = 73), clinicians (n = 58), journal editors (n = 47), and patients and members of the public (n = 17) (numbers are not mutually exclusive). During each survey round, participants rated the importance of modifications on a five-point Likert scale and provided comments or suggestions for additional items. A high level of agreement was defined by at least 80% of respondents rating the importance of a proposed modification as high (score of 4 or 5) or low (score of 1 or 2).

The Delphi survey results were then discussed at a two-day online consensus meeting in March 2023, attended by 30 invited international experts representing a range of relevant groups. Meeting participants discussed potential new and modified SPIRIT checklist items, with anonymous polling of participants in cases of ongoing disagreement.

The executive group met in person in April 2023 to develop a draft checklist based on the consensus meeting discussion. After a further round of review by consensus meeting participants, the executive group finalized the SPIRIT 2025 statement.

Updated SPIRIT 2025 statement

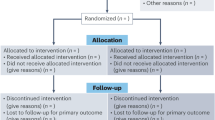

The SPIRIT 2025 statement comprises a checklist of 34 minimum protocol items (Table 1) and a diagram illustrating the schedule of enrollment, interventions and assessments (Table 2). An accompanying SPIRIT 2025 explanation and elaboration document provides background and context for each checklist item, along with examples of good reporting28. We strongly recommend that the SPIRIT 2025 explanation and elaboration document be used routinely alongside the SPIRIT 2025 statement to facilitate better understanding of and adherence to the checklist items.

To present the recommendations in diverse formats, we also developed an expanded version of the SPIRIT 2025 checklist with bullet points of key issues to consider for each item (Supplementary Table 1), as done with other initiatives29,30,31. The expanded checklist comprises an abridged version of elements presented in the SPIRIT 2025 explanation and elaboration document28, with examples and references removed.

Main changes

Substantive changes made in this update are detailed in Box 1. We added two new checklist items, revised the content of five items, deleted three items, merged two items and integrated key items from CONSORT Harms 2022 (ref. 24), SPIRIT-Outcomes 2022 (ref. 25) and TIDieR27 into the main checklist and explanatory document. We also restructured the SPIRIT checklist and created a new open science section consolidating items critical to promoting access to information about trial methods and results, including trial registration; sharing of the full protocol, statistical analysis plan and de-identified participant level data; and disclosure of funding sources and conflicts of interest. We have also harmonized the wording between SPIRIT and CONSORT checklist items and clarified the wording of some items. A comparison of the SPIRIT 2025 and 2013 checklists is available in Supplementary Table 2.

Definition of a randomized trial protocol

The protocol is a central document that provides sufficient detail to enable (1) understanding of the rationale, objectives, population, interventions, methods, statistical analyses, ethical considerations, dissemination plans and administration of the trial; (2) replication of trial methods and conduct; and (3) appraisal of trial validity, feasibility and ethical rigor14.

The full protocol must be submitted for approval by an REC/IRB before enrolling participants32. As a living document that is often formally amended during the trial13,33, every protocol version should contain a transparent audit trail documenting the dates and descriptions of changes. Important protocol amendments should be reported to REC/IRBs and trial registries as they occur, and subsequently described in reports of completed trials34.

Scope of SPIRIT 2025

SPIRIT 2025 addresses the minimum content of a protocol, focusing on the most common type of randomized trial — the two-group parallel design. However, most of the SPIRIT items are relevant to any type of trial. SPIRIT 2025 has been designed to complement and enhance the expanding trial registration requirements mandated by legislation, journals and funding policies35. SPIRIT 2025 encompasses and builds upon recommendations from the International Council for Harmonization Good Clinical Practice E6(R3) guidance36 and 2024 Declaration of Helsinki32, including the Declaration of Helsinki’s requirement that the protocol address potential conflicts of interest and provision of post-trial care.

It is feasible to address all SPIRIT 2025 checklist items in a single protocol document, as illustrated by the examples we identified from existing protocols for every item28. There are often related documents (for example, full statistical analysis plan37, data management plan) that provide further details on specific items. Any such documents should be referenced in the protocol and made available for review.

The main purpose of SPIRIT 2025 is to promote transparency and an adequate description of what is planned — not to prescribe how a trial should be designed or conducted. The checklist also does not focus on the protocol format, which is often subject to local regulations or practice. The checklist should not be used to appraise the quality of trial design or conduct, as it is possible for the protocol of a poorly designed trial to address all checklist items by fully describing its inadequate design and conduct features. Recent guidance from the World Health Organization (WHO) outlines best practices for designing and conducting trials38.

Implementation

The SPIRIT 2025 statement supersedes the SPIRIT 2013 statement, which should no longer be used or cited. We encourage research organizations, sponsors, funders, REC/IRBs, journal editors and publishers to endorse SPIRIT 2025 and request that they update their resources and instructions to research teams and reviewers with reference to the updated guidance.

When protocols are submitted for review or publication, we recommend the submission of a completed SPIRIT 2025 checklist that indicates where (for example, page number) checklist items are reported in the protocol. Trial investigators and sponsors should address all SPIRIT 2025 checklist items in the protocol before REC/IRB submission. If an item is not relevant for a particular trial (for example, no interim analysis planned), then this should be explicitly stated, along with an explanation. We encourage investigators to ensure consistency of information in the protocol, related documents (for example, full statistical analysis plan)37 and trial registry record39.

To facilitate implementation, a new SPIRIT–CONSORT website (https://consort-spirit.org) provides resources based on the SPIRIT and CONSORT 2025 statements, including a fillable checklist, protocol-writing tools, and training materials for researchers, trainees, journal editors, peer reviewers, patients and the public.

Limitations

As a minimum standard focused on parallel group randomized trials, SPIRIT 2025 may not encompass every protocol item relevant for a particular trial. For example, a factorial trial design has additional analytical considerations related to potential statistical interactions40, and trials evaluating patient-reported outcomes have specific considerations regarding data-collection methods41. Extensions to SPIRIT 2013 were developed to provide additional guidance on reporting different types of trial designs, data and interventions25,34,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. We will engage with the leaders of these extensions to implement a process for aligning them with the updated SPIRIT 2025 statement. In the meantime, we recommend that the existing version of the relevant SPIRIT extensions be used.

Potential impact

The updated SPIRIT 2025 statement and its accompanying explanation and elaboration document can be helpful in several ways. SPIRIT 2025 will continue to serve as an educational resource for new investigators, trainees, peer reviewers and REC/IRB members. The explicit incorporation of an open science section in the SPIRIT checklist will support the growing global push for greater transparency and sharing of trial materials and outputs to facilitate evidence synthesis and reproducibility of research.

Trial investigators can consult the guidance when drafting their protocols to ensure that all elements are addressed. Meta-research reviews of protocols have found improved completeness of protocol content after SPIRIT 2013 was introduced10,11,48,49. In addition to improved reporting, adherence to SPIRIT 2025 may promote high-quality trial design and implementation because SPIRIT is used during the planning stage of a trial. This provides an opportunity to improve the validity and successful completion of trials by reminding investigators about important issues to consider before the study begins. Better protocols can also help study personnel to implement the trial consistently across sites.

Another potential benefit of SPIRIT 2025 is its impact on administrative burden. Improved completeness of protocols may improve the efficiency of external review by reducing avoidable queries to investigators about incomplete or unclear protocol-related information50,51. High-quality protocols addressing all SPIRIT items may also help to reduce the number and burden of protocol amendments during the trial — many of which can be avoided with careful consideration of key issues when developing the protocol13,33. Widespread adoption of SPIRIT 2025 as a common standard across REC/IRBs, funding agencies, regulatory agencies and journals could simplify the work of trial investigators and sponsors because a SPIRIT-based protocol would then fulfil the harmonized application requirements of multiple groups.

Further, adherence to SPIRIT 2025 may help ensure that protocols contain the requisite information for critical appraisal and trial interpretation by peer reviewers, funders, REC/IRBs and journals7. High-quality protocols provide important information about trial methods and conduct that is usually not available in trial registries or publications reporting completed trials. As a transparent record of the investigators’ original intent, comparison of protocols with reports of completed trials helps to identify selective reporting of results and undisclosed amendments, such as changes to primary outcomes or analyses52,53. These benefits of SPIRIT based protocols can only be fully realized when trial protocols are routinely made publicly available through trial registries (for example, PDF upload), journals and online repositories7,54,55.

The SPIRIT 2025 statement incorporates new evidence and emerging perspectives to ensure that the guidance remains relevant to users. Widespread endorsement and adoption of the updated recommendations have the potential to improve protocol content and implementation; facilitate registration, oversight and appraisal of trials; and ultimately enhance transparency and translation to better healthcare.

References

Altman, D. G. Better reporting of randomised controlled trials: the CONSORT statement. BMJ 313, 570–571 (1996).

Strengthening the credibility of clinical research. Lancet 375, 1225 (2010).

Jones, G. & Abbasi, K. Trial protocols at the BMJ. BMJ 329, 1360 (2004).

Li, T. et al. Review and publication of protocol submissions to trials - what have we learned in 10 years? Trials 18, 34 (2016).

Krleza-Jerić, K. et al. Principles for international registration of protocol information and results from human trials of health related interventions: Ottawa statement (part 1). BMJ 330, 956–958 (2005).

Lassere, M. & Johnson, K. The power of the protocol. Lancet 360, 1620–1622 (2002).

Chan, A.-W. & Hróbjartsson, A. Promoting public access to clinical trial protocols: challenges and recommendations. Trials 19, 116 (2018).

Zarin, D. A., Fain, K. M., Dobbins, H. D., Tse, T. & Williams, R. J. 10-year update on study results submitted to ClinicalTrials.gov. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1966–1974 (2019).

Public Citizen Health Research Group v. Food and Drug Administration, 964 F Supp. 413 (DDC, 1997).

Gryaznov, D. et al. Reporting quality of clinical trial protocols: a repeated cross-sectional study about the Adherence to SPIrit Recommendations in Switzerland, CAnada and GErmany (ASPIRE-SCAGE). BMJ Open 12, e053417 (2022).

Speich, B. et al. A longitudinal assessment of trial protocols approved by research ethics committees: The Adherance to SPIrit REcommendations in the UK (ASPIRE-UK) study. Trials 23, 601 (2022).

Kasenda, B. et al. Agreements between industry and academia on publication rights: a retrospective study of protocols and publications of randomized clinical trials. PLoS Med. 13, e1002046 (2016).

Getz, K., Smith, Z., Botto, E., Murphy, E. & Dauchy, A. New benchmarks on protocol amendment practices, trends and their impact on clinical trial performance. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 58, 539–548 (2024).

Chan, A.-W. et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 158, 200–207 (2013).

Chan, A.-W. et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 346, e7586 (2013).

Hopewell, S. et al. CONSORT 2025 statement: updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ 389, e081123 (2025).

United Nations Educational Scientific Cultural Organization. UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science. UNESDOC Digital Library https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379949 (accessed 9 September 2024).

Hopewell, S. et al. An update to SPIRIT and CONSORT reporting guidelines to enhance transparency in randomized trials. Nat. Med. 28, 1740–1743 (2022).

Hopewell, S. et al. Protocol for updating the SPIRIT 2013 (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) and CONSORT 2010 (CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) Statements (version 1.0). (August 2022).

Tunn, R. et al. Methods used to develop the SPIRIT 2024 and CONSORT 2024 Statements. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 169, 111309 (2024).

Moher, D., Schulz, K. F., Simera, I. & Altman, D. G. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med. 7, e1000217 (2010).

Nejstgaard, C. H. et al. A scoping review identifies multiple comments suggesting modifications to SPIRIT 2013 and CONSORT 2010. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 155, 48–63 (2023).

Østengaard, L. et al. Development of a topic-specific bibliographic database supporting the updates of SPIRIT 2013 and CONSORT 2010. Cochrane Evid. Synth. Methods 2, e12057 (2024).

Junqueira, D. R. et al. CONSORT Harms 2022 statement, explanation, and elaboration: updated guideline for the reporting of harms in randomized trials. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 158, 149–165 (2023).

Butcher, N. J. et al. Guidelines for reporting outcomes in trial protocols: The SPIRIT-Outcomes 2022 Extension. JAMA 328, 2345–2356 (2022).

Boutron, I. et al. CONSORT Statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: A 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann. Intern. Med. 167, 40–47 (2017).

Hoffmann, T. C. et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 348, g1687 (2014).

Hróbjartsson, A. et al. SPIRIT 2025 Explanation and Elaboration: updated guideline for protocols of randomised trials. BMJ 389, e081660 (2025).

Barnes, C. et al. Impact of an online writing aid tool for writing a randomized trial report: the COBWEB (Consort-based WEB tool) randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 13, 221 (2015).

Chauvin, A. et al. Accuracy in detecting inadequate research reporting by early career peer reviewers using an online CONSORT-based peer-review tool (COBPeer) versus the usual peer-review process: a cross-sectional diagnostic study. BMC Med. 17, 205 (2019).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 10, 89 (2021).

World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. JAMA 333, 71–74 (2025).

Getz, K. A. et al. The impact of protocol amendments on clinical trial performance and cost. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 50, 436–441 (2016).

Orkin, A. M. et al. Guidelines for reporting trial protocols and completed trials modified due to the COVID-19 pandemic and other extenuating circumstances: The CONSERVE 2021 Statement. JAMA 326, 257–265 (2021).

Chan, A.-W. et al. Reporting summary results in clinical trial registries: updated guidance from the World Health Organization. Lancet Glob. Health 13, e759–e768 (2025).

International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) harmonised guideline. Guideline for good clinical practice, E6(R3). ICH https://www.ich.org/page/efficacy-guidelines (6 January 2025).

Gamble, C. et al. Guidelines for the content of statistical analysis plans in clinical trials. JAMA 318, 2337–2343 (2017).

World Health Organization. Guidance for best practices for clinical trials. WHO https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240097711 (accessed 9 September 2024).

Chan, A.-W. et al. Association of trial registration with reporting of primary outcomes in protocols and publications. JAMA 318, 1709–1711 (2017).

Kahan, B. C. et al. Consensus statement for protocols of factorial randomized trials: extension of the SPIRIT 2013 Statement. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2346121 (2023).

Calvert, M. et al. Guidelines for inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial protocols: The SPIRIT-PRO Extension. JAMA 319, 483–494 (2018).

Porcino, A. J. et al. SPIRIT extension and elaboration for n-of-1 trials: SPENT 2019 checklist. BMJ 368, m122 (2020).

Yap, C. et al. Enhancing quality and impact of early phase dose-finding clinical trial protocols: SPIRIT Dose-finding Extension (SPIRIT-DEFINE) guidance. BMJ 383, e076386 (2023).

Kendall, T. J. et al. Guidelines for cellular and molecular pathology content in clinical trial protocols: the SPIRIT-Path extension. Lancet Oncol. 22, e435–e445 (2021).

Cruz Rivera, S. et al. Guidelines for clinical trial protocols for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the SPIRIT-AI extension. Nat. Med. 26, 1351–1363 (2020).

Dai, L. et al. Standard Protocol Items for Clinical Trials with Traditional Chinese Medicine 2018: Recommendations, Explanation and Elaboration (SPIRIT-TCM Extension 2018). Chin. J. Integr. Med. 25, 71–79 (2019).

Manyara, A. M. et al. Reporting of surrogate endpoints in randomised controlled trial protocols (SPIRIT-Surrogate): extension checklist with explanation and elaboration. BMJ 386, e078525 (2024).

Blanco, D., Donadio, M. V. F. & Cadellans-Arróniz, A. Enhancing reporting through structure: a before and after study on the effectiveness of SPIRIT-based templates to improve the completeness of reporting of randomized controlled trial protocols. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 9, 6 (2024).

Tan, Z. W. et al. Has the reporting quality of published randomised controlled trial protocols improved since the SPIRIT statement? A methodological study. BMJ Open 10, e038283 (2020).

Happo, S. M., Halkoaho, A., Lehto, S. M. & Keränen, T. The effect of study type on research ethics committees’ queries in medical studies. Res. Ethics 13, 115–127 (2017).

Russ, H., Busta, S., Jost, B. & Bethke, T. D. Evaluation of clinical trials by Ethics Committees in Germany–results and a comparison of two surveys performed among members of the German Association of Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies (vfa). Ger. Med. Sci. 13, Doc02 (2015).

Meta-Research Group & Collaborators, T. A. R. G. Estimating the prevalence of discrepancies between study registrations and publications: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open 13, e076264 (2023).

Chan, A.-W., Hróbjartsson, A., Haahr, M. T., Gøtzsche, P. C. & Altman, D. G. Empirical evidence for selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials: comparison of protocols to published articles. JAMA 291, 2457–2465 (2004).

Schönenberger, C. M. et al. A meta-research study of randomized controlled trials found infrequent and delayed availability of protocols. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 149, 45–52 (2022).

Spence, O., Hong, K., Onwuchekwa Uba, R. & Doshi, P. Availability of study protocols for randomized trials published in high-impact medical journals: A cross-sectional analysis. Clin. Trials 17, 99–105 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We dedicate SPIRIT 2025 to the late Doug Altman, who was instrumental in the development of the SPIRIT and CONSORT statements and whose files and correspondence contributed to this update following his death. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all those who participated in the SPIRIT-CONSORT 2025 update Delphi survey. We also acknowledge Camilla Hansen Nejstgaard for conducting the scoping review to identify suggested changes to SPIRIT 2013 and for comparing SPIRIT 2025 with RoB2; Lasse Østengaard for developing the SCEB (SPIRIT-CONSORT Evidence Bibliographic) database of empirical evidence to support the development of SPIRIT 2025 and for assisting with handling references; Lina Ghosn for supporting the drafting of the expanded checklist; and Jen de Bayer and Patricia Logullo for their involvement during the consensus meeting.

SPIRIT-CONSORT executive group: Isabelle Boutron, Université Paris Cité, France; An-Wen Chan, University of Toronto, Canada; Sally Hopewell, University of Oxford, UK; Asbjørn Hróbjartsson, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; David Moher, University of Ottawa, Canada; and Kenneth Schulz, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA. Gary Collins and Ruth Tunn, both of University of Oxford, UK, were also involved in leading the SPIRIT and CONSORT 2025 update.

SPIRIT-CONSORT 2025 consensus meeting participants: Rakesh Aggarwal, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, India; Michael Berkwits, Office of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (formally JAMA and the JAMA Network at time of consensus meeting); Jesse A. Berlin, Rutgers University/JAMA Network Open USA; Nita Bhandari, Society for Applied Studies, India; Nancy J. Butcher, The Hospital for Sick Children, Canada; Marion K. Campbell, University of Aberdeen, UK; Runcie C.W. Chidebe, Project PINK BLUE, Nigeria/Miami University, Ohio, USA; Diana Elbourne, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK; Andrew J. Farmer, University of Oxford, UK; Dean A. Fergusson, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Canada; Robert M. Golub, Northwestern University, USA; Steven N. Goodman, Stanford University, USA; Tammy C. Hoffmann, Bond University, Australia; John P.A. Ioannidis, Stanford University, USA; Brennan C. Kahan, University College London, UK; Rachel L. Knowles, University College London, UK; Sarah E. Lamb, University of Exeter, UK; Steff Lewis, University of Edinburgh, UK; Elizabeth Loder, The BMJ, UK; Martin Offringa, Hospital for Sick Children Research Institute, Canada; Dawn P. Richards, Clinical Trials Ontario, Canada; Frank W. Rockhold, Duke University, USA; David L. Schriger, University of California, USA; Nandi L. Siegfried, South African Medical Research Council, South Africa; Sophie Staniszewska, University of Warwick, UK; Rod S. Taylor, University of Glasgow, UK; Lehana Thabane, McMaster University/St Joseph’s Healthcare, Canada; David Torgerson, University of York, UK; Sunita Vohra, University of Alberta, Canada; and Ian R. White, University College London, UK.

Funding: The 2025 update of SPIRIT and CONSORT was funded by an MRC-NIHR: Better Methods, Better Research grant (MR/W020483/1). The funder reviewed the design of the study but had no role in the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the MRC, or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Ethical approval: Ethics approval was granted by the Central University Research Ethics Committee, University of Oxford (R76421/RE001). All Delphi participants provided informed consent to participate.

Patient and public involvement: The SPIRIT 2025 checklist items and the explanations here were developed using input from an international Delphi survey and consensus meeting. The Delphi survey was advertised via established patient and public involvement (PPI) networks, and 17 respondents self-identified as a “patient or public representative” and completed the Delphi survey. In addition, three participants in the expert consensus meeting were patient or public representatives who were leaders in advancing PPI.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: SPIRIT 2025 will be disseminated via a new website, https://consort-spirit.org, which will include materials designed for patients and the public.

The SPIRIT 2025 statement is being simultaneously published in The BMJ, JAMA, The Lancet, Nature Medicine and PLoS Medicine. The articles are identical except for minor stylistic and spelling differences in keeping with each journal’s style.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.-W.C., I.B., S.H., A.H., D.M. and K.F.S. were responsible for the concept; and S.H., I.B., A.-W.C., G.S.C., A.H., K.F.S. and D.M. were responsible for the funding. A.-W.C., I.B., S.H., A.H., G.S.C., D.M. and K.F.S. drafted specific sections of the manuscript. A.-W.C. was guarantor of the work. All authors then critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at https://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare the following: support from MRC-NIHR for the submitted work; S.H., I.B., A.-W.C., A.H., K.F.S. and D.M. are members of the SPIRIT-CONSORT executive group. S.H., I.B., A.-W.C., A.H., K.F.S., G.S.C., D.M., M.K.C., N.J.B., M.O., R.S.T. and S.V. are involved in the development, update, implementation and dissemination of several reporting guidelines. G.S.C. is the director of the UK EQUATOR Centre and a statistical editor for The BMJ; D.M. is the director of the Canadian EQUATOR Centre and a member of The BMJ’s regional advisory board for North America; I.B. is deputy director and P.R. is director of the French EQUATOR Centre; T.C.H. is director of the Australasian EQUATOR Centre; J.P.A.I. is director of the US EQUATOR Centre; R.A. is president of the World Association of Medical Editors. M.K.C. is chair of the MRC-NIHR: Better Methods Better Research funding panel. R.C.W.C. is executive director of Project PINK-BLUE, which receives funding from Roche-Product. A.F. is director of the UK National Institute for Health and Care Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. D.P.R. is a full-time employee of Five02 Laboratories (which under contract to Clinical Trials Ontario and provides services related to patient and public engagement) and is the volunteer vice president of the Canadian Arthritis Patient Alliance (which receives funding through independent grants from pharmaceutical companies). D.L.S. is the JAMA associate editor and receives editing stipends from JAMA and Annals of Emergency Medicine. I.R.W. was supported by the MRC Programmes MCUU00004/07 and MCUU00004/09.

Peer review

Peer review information

Primary Handling Editor: Joao Monteiro, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, AW., Boutron, I., Hopewell, S. et al. SPIRIT 2025 statement: updated guideline for protocols of randomized trials. Nat Med 31, 1784–1792 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03668-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03668-w

This article is cited by

-

Efficacy and acceptability of a blended intervention for emotion regulation (MAISHA) among young people in Kenya: study protocol for a cluster RCT

BMC Psychology (2025)

-

A large language model for clinical outcome adjudication from telephone follow-up interviews: a secondary analysis of a multicenter randomized clinical trial

Nature Communications (2025)

-

The Power of Negative Autobiographical Memories: Regulating Affect Through Intensive Mindfulness and Compassion Interventions in a Crossover Design

Cognitive Therapy and Research (2025)

-

BLNK as an important prognostic indicator for survival in pediatric classic hodgkin lymphoma patients: a single-center retrospective study

Annals of Hematology (2025)

-

Lobectomy-first versus lymphadenectomy-first on long-term survival for operable non-small cell lung cancer: protocol of LOFTY trial

Trials (2025)