Abstract

Throughout the last centuries, European climate changed substantially, which affected the potential to plant and grow crops. These changes happened not just over time but also had a spatial dimension. Yet, despite large climatic fluctuations, quantitative historical studies typically rely on static measures for agricultural suitability due to the non-availability of time-varying indices. Relying on recent advances in paleoclimatology, we bridge this gap by constructing a spatio-temporal measure for agricultural suitability across Europe for a period of 500 years. Our gridded index has a 0.5° resolution and is available at a yearly level. It relies on a simple surface energy and water balance model, focusing only on so-called exogenous geographic and climatic features. Our index captures not just long-term trends, such as the Little Ice Age, but also short-term climatic shocks. It will empower researchers to explore the interplay between climatic fluctuations and Europe’s agricultural landscape, analyze human responses at a local and regional scale, and foster a deeper understanding of the region’s historical dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

“To understand our world’s changing climate, it is imperative that we understand how climates of the past varied. Paleoclimatic data are the language we use to look into the past to understand ourselves and ultimately our future.” — Dowsett, 20201

Climate change, referring to long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns, is one of the pressing topics of our time. Throughout the last years, it has received increasingly more attention, both from the public and from scientists. Climate change, however, is not a recent phenomenon. Advances in the field of paleoclimatology, the study of ancient climates prior to the widespread availability of instrumental records, allow us to increasingly understand what the Earth’s past climate was like. One of the main themes that emerges from these studies is that climate change not only had a temporal but also a spatial dimension.

The link between temperature and precipitation fluctuations and agricultural productivity is widely recognized in modern agriculture2. Crops rely on suitable growing conditions, including optimal temperatures and adequate soil moisture and nutrients, to successfully complete their life cycles3. Consequently, alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns directly impact the suitability of land for agricultural use4. Before the industrial era, when irrigation and chemical fertilizers were not yet prevalent, these climatic influences were even more significant. This dependency was reinforced at a societal level by the fact that over half of the population was directly involved in agriculture during pre-industrial times5,6. As a result, fluctuations in climate often had profound effects on both the economic system and human well-being by directly impacting agricultural productivity7,8,9.

These effects do not occur uniformly across space. Climate change, instead, also has the potential to change the geography of crop suitability4,10,11,12. The climatic, soil and topographic requirements may vary over a wide range of different geographic areas and the climate experienced at any one location is unique to that point, at no other location will an identical climate occur. Historical examples for heterogeneous shifts in agricultural suitability are well documented already for the 14th century13. The famine period from 1315-1322 in Northern Europe was driven by diminished crop yields due to wet and cold summers. After a shift of the Atlantic westerlies, rainfall increased in southern Europe, leading to harvest failures in the 1330s and 1340s without affecting the north in a similar fashion. The disappearance of viticulture that only occurred in the north of Europe would be another example14.

Given that climate can vary significantly over short distances, it is crucial for researchers working with disaggregated historical data to account for the spatial nuances and significance of micro-climates15. Despite the spatial and temporal nature of climatic change, until now, quantitative historical studies have primarily relied on static indices of agricultural suitability - mainly due to the lack of indices that vary over time.

In order to overcome this limitation, we combine recent advances in paleoclimatology and construct the first time-varying index for agricultural suitability in Europe from 1500 to 2000 at a yearly level. We use a simple surface energy and water balance model as proposed by Ramankutty et al.3. Specifically, we rely on spatio-temporal data for temperature by Luterbacher et al.16 and Xoplaki et al.17, and precipitation by Pauling et al.18. Previous research has demonstrated that a combination of growing season length and moisture availability to crops effectively encapsulates pertinent characteristics to define the cold and dry boundaries of agricultural land19. The remaining components of the index emphasize the vital significance of soil potential hydrogen (pH) and carbon content in delineating agricultural boundaries, which are fundamental in determining nutrient availability for crops and maintaining soil functionality3,20,21. The temporal and spatial extent, as well as the resolution at the 0.5° × 0.5° level, are imposed by these paleoclimatic datasets.

This novel index is able to capture not just long-term trends, such as the so-called Little Ice Age (LIA), but also short-term climatic shocks. Specifically, we illustrate that the index captures negative shocks on agriculture induced by both precipitation and temperature, highlighting the importance of looking at the joint role of these features, their interaction with local soil conditions and their non-linear impacts. For example, temperatures that are both too high and too low are detrimental to crops. The same holds for precipitation as drought-like conditions are not conducive to plant growth, whereas too much rainfall during summer and autumn constituted the greatest hazard to crops in pre-industrial Europe22,23. In addition, there are potential interactions, such as, for example, the combination of cold weather and droughts, which seem to have created the most unfavorable conditions for crop cultivation in Mediterranean Europe24. Their effects are thus non-linear and interact with each other, suggesting that some functional form is needed25.

Importantly, in the construction of the index, we deliberately abstain from incorporating any information on actual historical land use and only include features that are exogenous to human activity. This is in contrast to an interesting literature with a different goal which tries to estimate and reconstruct historical cropland cover26,27,28,29,30,31. Such an approach necessarily needs to make assumptions about the level and spatial distribution of population over time - which is something that is viewed as an endogenous outcome in the types of historical studies for which our index will be useful. Irrespective of that, population estimates before the 19th century, let alone their spatial distribution, are not well-known and often based on educated guesses and assumptions32.

Furthermore, we deliberately do not aim to estimate the potential agricultural output of a particular piece of land, which varied across time and space based on a multitude of institutional and cultural factors. For example, land-tenure systems, the type of crop-rotation, the availability of new-world crops, the availability of horses as draft animals, episodes of war or conflict, and many others. It is thus desirable to separate out land use and potential production and only focus on factors that are exogenously imposed by nature. Our index, therefore, aims to define the likelihood of an area being suitable for cultivation, irrespective of whether it was cultivated or not. This leaves ample room for the expert researcher of any study using our index to determine how much of the output is actually caused by the human-environment interaction and, therefore, makes it easier to alleviate concerns about environmental determinism7.

By capturing the evolution of agricultural suitability over time and space, our dataset will empower researchers to explore the interplay between climatic fluctuations and Europe’s agricultural landscape, analyze human responses at a local and regional scale, and foster a deeper understanding of the region’s historical dynamics. It will be particularly relevant for research in the area of ’history of climate and society’ (HCS), where recent emphasis has been placed on the need to account for local and spatio-temporal heterogeneity of past climate changes33. In studies that just wish to account for (exogenous) changes in agricultural suitability at a fine-grained level, our dataset will be a useful time-varying control variable, for example, in regression analysis.

Scholars across many disciplines have long traced the cascading effects of climate and geography in shaping societies34,35. Climate and land suitability for agriculture have historically influenced crop productivity and the essential role of agriculture in providing nutrients, calories, proteins, and vitamins. These factors not only fueled labor but also shaped the organizational frameworks of pre-industrial societies, setting the stage for modern energy transitions36. This perspective illuminates the profound influence of land’s capacity to sustain crops, whether in terms of overall suitability or specific crop requirements, in elucidating persistent developmental disparities, such as state formation37, distribution of economic activity38, structural transformation39, growth40, as well as time preferences41, cultural dynamics42, and cooperation43.

Therefore, understanding changes in agricultural suitability and its implications is crucial for assessing the role of human activity as a driver of global environmental change44. In this context, our study naturally attaches to studies analyzing the spatial and temporal dynamics of agricultural suitability in current times, emphasizing its critical importance for food security and its integration into climate change research45,46,47,48.

Understanding the past human-climate interrelationship is essential for decision-makers and institutions seeking to comprehend a range of issues and take effective actions in the future. Climate variability over the last millennium provides crucial context for assessing future changes, particularly as anthropogenic effects become increasingly dominant49. Our index will aid researchers in addressing important questions regarding the impact of changes in agricultural suitability induced by climate change on people’s lives and the economy in the past. This insight can inform strategies to tackle contemporary challenges, especially in low- and middle-income countries that are often highly vulnerable to climatic shocks.

Several different time-varying indices of agricultural suitability, covering periods starting from the 1960s, have been proposed4,44,50,51. Since all of them require a rich set of input variables with spatio-temporal variation, which are essentially only available since the advent of satellite data, none of these can be extended backward to cover longer periods of time. To overcome this, researchers working with historical data typically use either a static index3,41 or, e.g., choose one cross-section of the GAEZ index52 to proxy for suitability in pre-industrial times. Alternatively, if researchers are willing to disregard geographic variability, they could just use readily available paleoclimatic time series data measured for the entire continent or parts of it. Relying only on variation in temperature or rainfall in isolation in order to capture agricultural suitability, however, is not recommended due to interactive and non-linear effects, as pointed out above. Our paper is the first one to offer an index with temporal as well as geographic variation in agricultural suitability covering the European landscape from 1500 to 2000. The temporal and spatial coverage of our index is limited, however, we hope we were able to illustrate the immense usefulness of the geographical component of paleoclimatic data for social science research and spur further research in this area. Such advances would allow to extend our approach to areas outside of Europe and periods farther back in time.

The most comparable paper to our work is the spatially explicit Old-World Drought Atlas (OWDA)53, which is a 0.5° gridded tree-ring based reconstruction of soil moisture spanning the entire common era. OWDA estimates a boreal summer self-calibrating Palmer’s Drought Severity Index (scPDSI), therefore focusing on severe drought and wetness. These precipitation-related events are usually the ones that trigger famine54, and the OWDA is thus able to capture extreme outlier events well. Especially in the North of Europe, however, crop cultivation is often found to be much more temperature sensitive23. Droughts are also typically much more spatially restricted than temperature anomalies55. Our index takes this into account and also captures more nuanced suitability fluctuations that naturally occurred due to changes in both temperature and precipitation.

The article is organized as follows: The Methods section provides an in-depth exploration of our approach, offering a schematic overview of the methodology (Fig. 1), and detailing the various building blocks that constitute our index. In the Data records section, we describe the dataset along with instructions for accessing and downloading it. Finally, we offer an overview of our index and conduct a technical validation with relevant benchmark indices.

Study design. Historical temperature data are taken from Luterbacher et al.16 and Xoplaki et al.17. Historical precipitation data are from Pauling et al.18. Windspeed, humidity, elevation, and sunshine hours are taken from the Climate Research Unit (CRU) CRU v.2.0 dataset58. Soil characteristics such as carbon content and soil pH are from the Harmonized World Soil Database59.

Methods

Agricultural suitability is influenced by natural constraints, including local climate, soil characteristics, and topography, which collectively determine the availability of energy, water, and nutrients necessary for crop cultivation. Changes in temperature and precipitation patterns directly impact the suitability of land for agricultural use4, however, the specific impact of these climatic factors varies widely based on crop type, geographical location, production practices, and technological advancements56.

Our agricultural suitability index follows the approach by Ramankutty et al.3 and consists of four main building blocks: a measure for cumulative temperature exposure (growing degree days), a measure for soil moisture (aridity index), the carbon content of the soil, and its potential hydrogen value. Land suitability is then defined as the predicted value of the propensity of a given piece of land to be suitable for cultivation.

By choosing a simple surface energy and water balance model, we illustrate how existing spatio-temporal paleoclimatic data can be used to create a spatially explicit suitability index that reaches several centuries into the past. Importantly, we are relying on temporal variation only from rainfall and temperature, sources that are exogenous to human activity in Europe - at least in our historical context. Since one of the primary uses of this index is to help scholars study how climate change affected human behavior in the past, it would be far from ideal to incorporate human behavior itself into the index. It would, in fact, induce a form of circular reasoning that would make it difficult to distinguish cause from effect.

This section describes in detail how each of these blocks were constructed and how we combine them into an index at a yearly level. The time frame and the spatial extent of our index were dictated by the spatio-temporal historical data on temperature and precipitation which are the main inputs.

Data overview

The starting point of our data construction is a uniform grid with dimensions of 0.5° × 0.5°, bounded by the following geographical coordinates: 25° W to 40° E and 35° N to 70° N. The core historical climate datasets under investigation include temperature data16,17 and precipitation data18. These datasets provide reconstructed seasonal temperature values (in degrees Celsius) and precipitation values (in millimeters) for four seasons (Autumn, Winter, Spring, and Summer) at a 0.5° × 0.5° grid resolution (approximately 55km by 55km measured at the equator). Our constructed initial grid aligns with these data sources.

To construct a comprehensive crop suitability index, we have adopted the methodology introduced by Ramankutty et al.3 as our foundational framework. This index integrates multiple critical factors, including growing degree days, soil moisture, soil pH, and carbon content, as primary determinants of soil suitability. Due to the lack of temporal data on soil parameters, we assume that soil pH and carbon content remain constant over time, attributing temporal variability exclusively to growing degree days and the soil moisture index. Numerous inputs were indispensable for the computation of various parameters, extending beyond just temperature and precipitation data. We incorporated additional environmental variables such as potential sunshine hours, average wind speed, relative humidity, and elevation. A comprehensive description of all the data utilized in this study is provided bellow:

Historical temperature

In this study, we employ the European Seasonal Temperature Dataset, constructed by Luterbacher et al.16 and Xoplaki et al.17. This dataset represents a high-resolution grid (0.5° × 0.5°) capturing seasonal temperature patterns across European land areas spanning from 25° W to 40° E and 35° N to 70° N from the year 1500 to 2000. The dataset draws upon various sources, incorporating homogenized and quality-assured instrumental data series, historical records documenting sea-ice and temperature indices from past centuries, and seasonally resolved proxy temperature reconstructions sourced from Greenland ice cores and tree rings originating from Scandinavia and Siberia16,17. The dataset segments the year into four distinct seasons, each spanning three months: winter (December, January, and February), spring (March, April, and May), summer (June, July, and August), and autumn (September, October, and November). To match the resolution and grid structure, the data has been resampled by extracting the seasonal mean value for every cell to our grid covering Europe, specifically ranging from 25° W to 40° E and 35° N to 70° N.

Link to data: Historical temperature (https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/projects/soap/data/recon/#paul05).

Historical precipitation

We exploit the historical precipitation dataset sourced from the work of Pauling et al.18. This gridded dataset (0.5° × 0.5°) encompasses the European landscape extending from 30° W to 40° E and from 30° N to 71° N. It provides a comprehensive view of precipitation patterns from the year 1500 to 1900, also incorporating the gridded reanalysis data spanning the years 1901 to 2000 documented by Mitchell et al.57. The construction of this dataset required the use of advanced statistical techniques, prominently employing Principal Component Regression methods. It combines an extensive array of data sources, including long instrumental precipitation records, precipitation indices rooted in historical documentation, and natural proxies such as tree rings chronologies, ice cores, corals, and speleothems, all sensitive to precipitation signals18. Similar to the historical temperature dataset, it segments the year into four distinct seasons, each spanning three months: winter (December, January, and February), spring (March, April, and May), summer (June, July, and August), and autumn (September, October, and November). To match the resolution and grid structure, the data has been resampled by extracting the seasonal mean value for every cell to our 0.5° grid covering Europe, specifically ranging from 25° W to 40° E and 35° N to 70° N.

Link to data: Historical precipitation (https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/projects/soap/data/recon/#paul05).

Other surface climate

The remaining surface climate data has been gathered from the CRU v.2.0 dataset58. This dataset is a reconstruction of a 10-minute latitude/longitude data set of mean monthly surface climate over the global land area, excluding Antarctica. In this study, we used four climate elements from this dataset: relative humidity, sunshine duration, wind speed, and elevation. These elements were interpolated from the data set of station means for the period 1961 to 1990. To match the resolution and grid structure, the data has been resampled by extracting the seasonal mean value for every cell to our 0.5° grid covering Europe, specifically ranging from 25° W to 40° E and 35° N to 70° N.

Link to data: CRU V.2.0 (https://crudata.uea.ac.uk).

Soil characteristics

Soil data parameters have been sourced from the Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD)59, a repository renowned for its comprehensive representation of soil characteristics. The re-gridded HWSD dataset is presented in the form of files at a resolution of 0.05°, encompassing a diverse array of soil attributes. These attributes encapsulate information derived from actual soil profiles, reflecting varying stages of pedogenic evolution, land utilization, historical land use, and past disturbances. Within the HWSD, soil properties are accessible for both surface soil horizons (ranging from 0 to 30 cm) and deeper soil profiles (spanning depths of 30 to 100 cm)59. For our specific investigation, we have carefully chosen two pivotal components essential for assessing crop suitability: topsoil carbon content (T_C, in kg C m-2) and topsoil pH (T_PH_H20, in H20, −log(H+)). To match the resolution and grid structure, the data has been resampled by extracting the seasonal mean value for every cell to our 0.5° grid covering Europe, specifically ranging from 25° W to 40° E and 35° N to 70° N.

Link to data: HWSD (https://daac.ornl.gov).

Actual agricultural suitability

Our model is calibrated to the most recent and precise measure of suitability sourced from the FAO GAEZ v4 data portal. To align with the scope of our study, we constructed the actual measure of agricultural suitability by considering an average of four main types of crops historically prevalent in pre-industrial Europe: wheat, oat, rye, and barley. These crops were assessed over the time period of 1971-2000 under rainfed conditions and low input levels without considering CO2 fertilization effects. The resulting index has been normalized to a scale from 0 to 1 and then extracted to a grid with a resolution of 0.5° covering the European landscape, specifically ranging from 25° W to 40° E and 35° N to 70° N.

Link to data: FAO GAEZ v4 Data Portal (https://gaez.fao.org).

Administrative units

The polygon delineating the coastlines of Europe is taken from Natural Earth. The dataset represents land polygons, including major islands at 1:50m covering the extent of the study: 25° W to 40° E and 35° N to 70° N.

Link to data: Natural Earth, version 4.0.0. (https://www.naturalearthdata.com).

Data processing

We processed the data in two primary stages. First, all geographic datasets were resampled extracting the mean value for each input within our 0.5° grid to ensure uniform spatial resolution and grid structure. Second, specific adjustments were made to certain inputs to meet some functional form requirements, particularly for incorporation into the evapotranspiration calculations.

For instance, potential sunshine hours per day were derived using the percentage of daylight (Sun) from the CRU dataset58, capped at a maximum of 11 hours per day in accordance with the World Meteorological Organization Standard Normals (https://data.un.org). Additionally, wind speed data provided at 10 meters height (U10) in the CRU dataset58 was adjusted to a 2-meter height (U2) using a logarithmic wind profile appropriate for measurements over short grassed surfaces, with the relationship approximated as U2 = 0.75U10, following and established methodology60.

Furthermore, seasonal temperature extremes were calculated by identifying the minimum (\({T}_{\min }\)) and maximum (\({T}_{\max }\)) temperatures for each grid cell across the four seasons. Precipitation (P) in mm/year was computed as the total annual sum across these seasons. For detailed information on the variables used, their sources, the specific processing steps undertaken, and the final outputs, please refer to Table 1.

Building blocks for the suitability index

To construct a comprehensive crop suitability measure, in line with the approach outlined by Ramankutty et al.3 as our foundational framework, we require four key components: growing degree days, soil moisture, soil pH, and carbon content, which collectively serve as the primary determinants of agricultural suitability. In the upcoming sections, we will provide an overview of the four parameters and their significance in evaluating crop development.

Growing Degree Days (GDD)

GDD serves as a vital metric for estimating the growth and developmental progress of plants and insects during the active growing season. It is commonly used in the agronomic literature as a measure for cumulative temperature exposure61. The concept is based on the notion that development occurs only when temperatures surpass a minimum developmental threshold, typically set at 5° C for most European crop varieties, as depicted by the European Environment Agency (EEA, https://www.eea.europa.eu).

Originally, GDD is computed by summing daily temperature values over the course of a year. However, given our dataset’s lack of daily temperature observations, we have tailored the calculation of the GDD to align with our available seasonal data. To achieve this, we have evenly distributed the weight of each season, consisting of approximately 91 days, to construct the GDD measure for each year t from 1500 to 2000. The four seasons represent averages over 3 months as follows: Winter (December, January, February), Spring (March, April, May), Summer (June, July, August), and Autumn (September, October, November). Hence, this measure, contingent on the average seasonal temperature i in year t, is defined as follows:

Aridity Index (AI)

We employ the AI as a proxy for soil moisture. The AI is a straightforward and widely accepted measure of aridity, rooted in the assessment of long-term climatic water deficits62. Beyond its role in forecasting drought and flood patterns, such indices are recognized for their utility in gauging moisture availability, crucial for the potential growth of reference crops and various vegetation types63.

Aridity can be expressed as a generalized function of the ratio of precipitation over potential evapotranspiration (PET, or ET0 in our case).

Evapotranspiration (ET) constitutes a pivotal phenomenon within the realm of biology, with particular significance in the study of crop water requirements. Over the different measures of potential water loss, reference evapotranspiration (ET0) is considered a more suitable indicator for estimating potential evapotranspiration compared to temperature-based metrics due to its utilization of an energy balance approach64.

ET0 can be computed according to the Penman-Monteith equation, which calculates the rate of ET from a hypothetical reference crop characterized by a standard crop height of 12 cm, a consistent canopy resistance of 70 ms−1, and an albedo of 0.23, closely resembling the rate of ET from an extensive expanse of green grass65,66. To execute the computation of ET0 effectively, the model needs several input parameters such as potential sunshine hours per day SD (hours), wind speed U2 (ms−1), mean daily relative humidity RH (%), latitude L (deg), elevation A (m), minimum temperature Tmin (°C), maximum temperature Tmax (°C) and mean temperature Ta (°C).

To ensure uniformity and relevance, we undertook specific data transformations. Notably, we converted the potential sunshine dataset from CRU, originally expressed as a percentage, into potential sunshine hours by imposing a maximum of 11 hours of daylight, using country averages from the World Meteorological Organization Standard Normals. Furthermore, we adjusted the wind speed data, initially measured at a height of 10 meters, to the standard measurement height of 2 meters. This adjustment was made using a logarithmic wind speed profile for measurements conducted above a short grassed surface60, resulting in an approximate equivalence of U2 = 0.75U10. All necessary inputs are comprehensively described in Table 1.

We provide below a step-by-step derivation of the different parameters necessary to compute ET0 following the method described by the FAO GAEZ framework67.

1) Latent heat of vaporization (λ, in MJ kg−1) represents the amount of energy required to change a unit mass of liquid into vapor at a given temperature location (Ta).

2) Atmospheric pressure (P, in kPa) is the pressure exerted by the weight of the earth’s atmosphere. Measured using elevation above sea level in meter (A), at higher altitudes where atmospheric pressure is lower, evaporation tends to occur more readily due to reduced pressure.

3) Psychrometric constant (γ, in kPa°C−1) serves as a bridge between the partial pressure of water vapor in the air and the air temperature. Given that atmospheric pressure (P) changes with altitude, the psychrometric constant (γ) also varies accordingly. Consequently, water evaporates at higher altitudes and boils at lower temperatures due to the decrease in atmospheric pressure depending on the latent heat of vaporization (λ).

4) Aerodynamic resistance (ra) determines the transfer of heat and water vapor from the evaporating surface into the air according to wind speed measurement at 2 m (U2). Assuming a constant crop height of 0.12 m and a standardized height for wind speed at 2 m, temperature, and humidity at 2 m, the aerodynamic resistance ra for the grass reference surface can be approximated as follows:

5) Crop canopy resistance (rc) relates to the resistance offered by the crop canopy to the transfer of water vapor from the leaves to the atmosphere. It represents the extent to which the crop canopy limits the evapotranspiration process. Setting the average daily stomata resistance of a single leaf (Rl) equal to 100, and a leaf area index of the reference crop (LAI) at 2.8867, rc can be computed according to the following equation:

6) Modified psychrometric constant (γ*, in kPa°C−1) can be computed using previous steps.

7) Saturation vapor pressure (ea, in kPa) represents the maximum amount of water vapor that air can hold for given minimum and maximum temperatures Tmin and Tmax. At higher temperatures, the saturation vapor pressure increases because warmer air can hold more moisture, while at lower temperatures, the saturation vapor pressure decreases.

8) Vapor pressure at dew point (ed in kPa), i.e. at the temperature at which water vapor begins to condense into water can be computed using relative humidity (RH, in %) and saturated vapor pressure eax and ean.

9) Slope vapor pressure curve (ϑ, in kPa°C−1) gives the relationship between saturation vapor pressure (eax and ean) for given temperatures Tmax and Tmin:

10) Latitude (φ, in rad) using latitude (L) in degree.

11) Solar declination (δ, in rad) varies throughout the year due to the tilt of the Earth’s axis relative to its orbit around the Sun. It can be approximated using the Spencer formula68.

Where τ is called the day angle (in radian) and depends on the Day of the Year (J).

12) Relative distance Earth to Sun (d) throughout the year, as influenced by the Earth’s elliptical orbit around the Sun and the tilt of its axis.

13) Sunset hour angle (Ψ, in rad) to determine the timing of sunset using the latitude in rad (φ) of the location and the solar declination angle in rad (δ).

14) Extraterrestrial radiation (Ra, in MJ m−2d−1) refers to the amount of solar radiation received at the top of the Earth’s atmosphere under ideal conditions, assuming there are no atmospheric factors such as clouds, haze, or air pollution to attenuate the solar radiation. The computation of the extraterrestrial radiation is found using the relative distance from Earth to the Sun (d), the sunset hour angle (Ψ, in rad), the latitude (φ, in rad), and the solar declination (δ, in rad) previously computed.

15) Maximum daylight hours (DL) represents the theoretical maximum duration of daylight at a specific location for a given day given the sunset hour angle (Ψ).

16) Short-wave radiation (Rs, in MJ m−2d−1) gives the solar radiation received at the Earth’s surface given sunshine hours per day (SD), maximum daylight hours (DL) and extraterrestrial radiation (Ra).

17) Net incoming short-wave radiation (Rns, in MJ m−2d−1) represents the solar radiation absorbed by the Earth’s surface depending on short-wave radiation (Rs), contributing to surface heating and various environmental processes. Assuming an albedo coefficient (α) of 0.23 for a reference crop, the net incoming radiation is defined as follows67.

18) Net outgoing long-wave radiation (Rnl, in MJ m−2d−1) is the energy emitted by the Earth’s surface in the form of long-wave infrared radiation, primarily due to its temperature. Given sunshine hours per day (SD), maximum daylight hours (DL), the vapor pressure at dew point (ed), maximum and minimum temperature (Tmax and Tmin), the net outgoing long-wave radiation is computed as follow.

19) Net radiation flux at surface (Rn, in MJ m−2d−1) gives the balance between incoming solar radiation absorbed by the Earth’s surface (Rns) and outgoing long-wave radiation emitted by the surface (Rnl).

Wrapping up the inputs we have computed in the previous steps, we can define an aerodynamic (ETar) and radiation (ETra) term according to the Penman-Monteith combination equation51. While the computation of soil heat flux (G) holds significance at the monthly level, its relevance diminishes considerably on a larger spatial scale, raising the potential for inaccuracies in its estimation63. Therefore, in our study, we opt to omit the computation of the soil heat flux (G) altogether, effectively setting it to zero (G = 0).

The output is a 0.5° × 0.5° set of grids indicating the yearly measure of ET0 in millimeters per day from 1500 to 2000.

20) Reference evapotranspiration (ET0, in mm per day).

Soil pH and carbon content

In line with the methodology outlined by Ramankutty et al.3, we designate soil pH and carbon content within the topsoil, where the majority of crop roots reside, as pivotal factors in determining soil suitability for agricultural purposes.

Primarily, soil pH, a fundamental parameter, profoundly influences soil fertility and nutrient availability, thereby directly impacting crop productivity. Lower pH levels, indicative of soil acidity, can impede the accessibility of essential plant nutrients while facilitating the uptake of detrimental elements such as aluminum, manganese, and hydrogen, along with the leaching of vital nutrients like calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium69. Conversely, elevated soil pH, characteristic of alkaline soils, hampers crop growth and yield by altering nutrient availability and disrupting natural microbial communities. The presence of sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) and sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) exacerbates these challenges, inducing nutritional stress and iron deficiency in plants and ultimately diminishing crop yields21.

Secondly, soil organic carbon assumes a pivotal role in determining soil functionality and ecological services. Its presence significantly enhances various chemical properties of soil, including infiltration capacity, water-holding ability, and nutrient availability for crops20. Nevertheless, low levels of organic carbon may indicate nutrient deficiencies, rendering the soil unsuitable for cultivation. Conversely, excessively high organic matter content can exacerbate water retention, leading to waterlogging conditions in poorly drained soils, thereby rendering them unsuitable for optimal crop growth3.

To assess topsoil suitability conditions, we utilized data from the Harmonized World Soil Database59, which provides measurements of pH (in H2O −log(H+)) and carbon content (in kg C m-2) at depths ranging from 0 to 30 cm.

Computation of agricultural suitability measure

In the following, we show how the building blocks are combined in order to obtain a yearly index.

Model calibration

In line with the methodology outlined by Ramankutty et al.3, the determination of our agricultural suitability index relies on functions denoted as f(GDD), f(AI), f(C), and f(pH), each detailed below. These functions are established by fitting curves to capture the relationship between actual agricultural suitability and the four parameters: GDD, AI, C, and pH. Essentially, each functional form represents the probability of suitability as a function of these input parameters.

To avoid dependence on historical endogenous cropland cover maps, we opted to construct the actual agricultural suitability by averaging the suitability indices of major crops historically present in the region. In pre-industrial Europe, wheat, rye, barley, and oat were the predominant crops, with rice, maize, and potatoes becoming significant only in later centuries in certain regions36.

To align with our most recent observations, we collected the suitability indices of wheat, rye, barley, and oat across from the FAO GAEZ data portal to our 0.5° × 0.5° grid covering the European landscape for the period 1971-2000. To simulate historical conditions accurately, these measures were constructed under rain-fed conditions, low input levels, and without CO2 fertilization. Subsequently, the suitability indices of different crops were averaged and scaled over the grid to yield a normalized index of actual agricultural suitability ranging from 0 to 1.

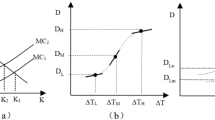

For the GDD and AI, we employed simple sigmoidal curves, terminating the curve fitting when reaching the first peak. This approach aligns with prior research indicating that a combination of growing season length and moisture availability effectively delineates the cold and dry boundaries of agricultural land19. While GDD indicates sufficient warmth for cultivation, AI accounts for plant-available moisture. The functional forms are calibrated as follows:

Where GDD2000 represents the average GDD measure over the period 1971-2000 to match the FAO suitability measure. The fitting yields a = 0.0079 and b = 982.75.

Where AI2000 denotes the average AI measure over the period 1971-2000 to align with the FAO suitability measure. The fitting gives a = 22.95 and b = 0.237.

The choice of a double sigmoidal curve to model the relationship between carbon content (C) and agricultural suitability is underpinned by key agricultural and environmental considerations. Soil carbon content, serving as a measure of the total organic content within the soil, plays a pivotal role in determining nutrient availability for crop growth. A low soil carbon content implies limited nutrient availability, thereby restricting optimal plant development and agricultural productivity. Conversely, excessively high soil carbon content levels often indicate waterlogging, particularly prevalent in wetland areas. In such instances, soil drainage becomes imperative for cultivation, necessitating significant investment in land preparation3. Hence, the functional form is calibrated as follows:

The fitting gives a = 0.99, b = 1.7, c = 2.345, d = − 0.458 and e = 14.347.

The representation of soil pH (pH) involves a composite of fitted lines, each delineating distinct pH ranges and their respective effects on soil suitability for cultivation. Soil pH levels significantly impact soil fertility and nutrient availability, thus influencing agricultural productivity. Extremely low pH levels characterize overly acidic soils, while excessively high pH levels denote soil alkalinity, both of which are unsuitable for cultivation. As soil pH gradually increases from toxic conditions towards the optimal range, nutrient availability improves, consequently enhancing the probability of successful cultivation until reaching an optimal plateau, as depicted by the first fitted line. Soil with pH values ranging between 6.5 and 7 represents an ideal range for cultivation, as indicated by the second flat line, reflecting optimal soil conditions conducive to crop growth. However, as soil pH continues to rise beyond the optimal range, nutrient availability diminishes under alkaline conditions, leading to decreased suitability for cultivation, as depicted by the third fitted line3. The functional representation of f(pH) incorporates these considerations, with parameters tailored to capture the nuanced relationship between pH levels and agricultural suitability. Specifically, the function f(pH) is defined as follows:

Figure 2 gives a visual representation of the different fitting curves. It is important to note that, in contrast to the study by Ramankutty et al.3, which employs a soil moisture index derived from the ratio of actual evapotranspiration (ETa) to potential evapotranspiration (PET), we have opted to utilize the AI as a proxy for soil moisture. This decision allows us to directly incorporate precipitation as a crucial factor in assessing agricultural land suitability and overcomes the limitation on historical temporal data for inputs necessary to compute the rate of ETa.

Calibration of the model using the FAO suitability index, growing degree days (GDD), the aridity index (AI), soil potential hydrogen, pH (in H20 −log(H+)) and carbon content, C (kg C/m2). Each point on the x-axis represents observations averaged over bins, and values on the y-axis correspond to the best suitability value reached by each bin. Selected points have for each calibration (except for their own): 4 < Csoil < 10, AI > 0.5, GDD > 1300, 6 < pHsoil < 8. The lines represent the different fitting curves: f(GDD), f(AI), f(C), f(pH).

Combining the building blocks

By incorporating time-varying parameters denoted as AIt and GDDt with soil suitability conditions C and pH, our agricultural suitability metric is constructed on an annual basis, combining the four foundational components described previously:

As each of the different functions produces values between 0 and 1, the product of the four parameters always generates a value between 0 and 1 by construction. In practical terms, this computation yields a spatial grid at a resolution of 0.5° × 0.5°, defined as the yearly probability for a given piece of land to be suitable for cultivation based on four distinct climatic and soil factors. It deliberately does not account for the potential agricultural output of a particular piece of land, which varied across time and space based on a multitude of factors. For example, institutional factors such as land-tenure systems, the type of crop rotation, the availability of new-world crops (which only started to diffuse later), the availability of horses as draft animals, or agricultural technology. In short, we try to abstract from possibly everything endogenous to human activity - which, we hope, makes the index appealing for many research applications.

Figure 3 presents the time series of the agricultural suitability index, averaged across Europe, accompanied by a 25-year moving average. The first time series underscores the notable impact of temperature and precipitation fluctuations on the suitability index. The moving average, on the other hand, elucidates overarching trends more distinctly. It delineates the peak of the Little Ice Age in the 16th and 17th centuries, succeeded by nearly a century of increase. Notably, around the time of the French Revolution, the index embarks on a century-long decline. From 1900 onward, a sustained ascent becomes evident, driven by the well-documented rise in average temperatures expounded upon in the contemporary climate change literature.

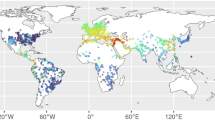

Figures 4 and 5 visually depict the spatial variability of different climate indices and the suitability index for selected years marked by “extreme events”. In the year 1669 AD (Fig. 4), Europe experienced one of the lowest mean levels of precipitation, totaling 622.62 millimeters for the year, whereas 1775 AD (Fig. 5) represented the most suitable year with a mean suitability index of 0.55 across Europe. Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the temperature and precipitation time series respectively, where these events are discernible. In 1695 AD, the lowest temperature level over Europe was estimated with a daily mean of 5.37 °C. In 1720 AD, the highest level of precipitation was observed, with an average of 808.65 millimeters over Europe. The lowest amount of yearly precipitation occurred in 1686 AD with an average of 620.8 millimeters. Regarding agricultural suitability, 1902 AD represented the least suitable year, with a mean suitability index of 0.434 across the continent. Finally, 1989 AD estimated the highest temperature in Europe, with a daily mean of 8.67 °C. While these snapshots represent only a few among numerous maps, the diverse nature of these shocks underscores the significance of their spatial dimension and their interaction with other climate and soil variables.

Case study 1 (1669 AD). The left panels show the mean precipitation18, mean temperature16,17, and our measure of agricultural suitability for the year 1669, where we register one of the lowest levels of precipitation across Europe (662.62 mm over the year). Z-score values (right panels) for each grid i have been computed using the standard formula: Z-scorex,i,t = (xi,t − μx,i)/σx,i where \({\mu }_{{x}_{i},i}\) and σx,i are the mean and standard deviation of variable x in grid i over the 1500-2000AD period respectively. xi,t is either yearly mean temperature, precipitation, or mean agricultural suitability for grid i at time t.

Case study 2 (1775 AD). The left panels show the mean precipitation18, mean temperature16,17, and our measure of agricultural suitability for the year 1775, where we register the highest overall mean of agricultural suitability across Europe (0.55). Z-score values (right panels) for each grid i have been computed using the standard formula: Z-scorex,i,t = (xi,t − μx,i)/σx,i where \({\mu }_{{x}_{i},i}\) and σx,i are the mean and standard deviation of variable x in grid i over the 1500-2000AD period respectively. xi,t is either yearly mean temperature, precipitation, or mean agricultural suitability for grid i at time t.

In 1669 (Fig. 4), temperatures in Western Europe were up to 1.20 standard deviations above their mean, while temperatures in the remaining part of the continent remained relatively stable. This temperature increase could be interpreted as having a positive impact on crop suitability, particularly evident through the GDD measure. However, Central Europe experienced extremely low levels of precipitation, with some regions recording deviations of up to -5 standard deviations from the usual levels. Two notable observations can be made regarding the change in agricultural suitability for that year. Firstly, the combination of relatively high temperatures and extremely low precipitation significantly reduced soil moisture available for plants through the AI, rendering most areas unsuitable for cultivation, with some areas deviating by up to -22 standard deviations from the usual values. Secondly, the increase in temperature in the arid part of the study area (Southern Europe and Northern Africa) was counterbalanced by higher levels of precipitation, providing sufficient moisture to compensate for the temperature increase and thereby enhancing the agricultural suitability of the area.

In our second case study (Fig. 5), dated back to the year 1775 AD, we observed the highest suitability index (0.55). While Southern Europe and Northern Africa experienced a decline in suitability due to the interplay of higher temperatures and reduced precipitation, Eastern Europe witnessed a notable uptick in suitability primarily attributed to temperature rise. This case study underscores an important insight: regions traditionally deemed too cold for sustained cultivation, especially those hovering around the 5°C threshold conducive to crop growth, stand to gain the most from temperature increases. Such temperature shifts, when coupled with appropriate moisture levels and soil conditions, have the potential to metamorphose previously unsuitable areas into viable cultivation zones. A pertinent example is Northern Europe, where land suitability saw a remarkable rise, reaching values up to 4.50 standard deviations above the norm, spurred by elevated temperatures peaking at 1.80 standard deviations above the mean level. This illustrates how changes in temperature, particularly in regions near the colder boundary for cultivation, can profoundly influence crop suitability, opening new avenues for agricultural productivity in areas once deemed largely unsuitable.

The importance of changes in climate conditions is also noteworthy and varies depending on soil conditions. Areas with different soil suitability conditions will be impacted differently by climate shocks, with areas having less suitable soil being more vulnerable to significant climate shocks. Conversely, areas with relatively high soil suitability, while negatively impacted by the shock, could potentially still sustain cultivation due to their favorable soil conditions. Thus, understanding the interplay between climate and soil conditions is crucial for predicting the resilience of agricultural systems to climate change.

While it is acknowledged that more sophisticated tools for measuring crop suitability over time have been developed, particularly the FAO GAEZ grids available for periods from 1960 onwards50, for periods in the 20th century, our index remains valuable for studies requiring consistent, uninterrupted suitability measurements spanning multiple centuries, thereby avoiding structural discontinuities in the dataset.

Data Records

The agricultural suitability index presented in this paper is available on the Harvard Dataverse70 (https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ECWMZS).

Users of the statistical programming language R have the option to directly load the data through the environmentalhist package (https://github.com/axlehner/environmentalhist). The dataset provides a reconstruction of agricultural suitability for the European landscape ranging from 25° W to 40° E and 35° N to 70° N at a 0.5° × 0.5° resolution for the 1500–2000 period in GeoTIFF (.tif) format:

suit.tif

Geospatial raster dataset with 501 bands representing the annual average agricultural suitability index for the period from 1500 to 2000. The index ranges from 0 (unsuitable for cultivation) to 1 (highly suitable for cultivation).

Technical Validation

Validating our agricultural suitability index presents challenges due to its pioneering nature and the lack of comparable historical data. As the first to develop a time-varying index reaching back beyond the mid-20th century, we lack benchmarks to technically validate for the earlier time periods. Additionally, agricultural output data linked to specific geolocations is sparse prior to the 20th century, further complicating validation efforts. However, we believe that technical validation only on periods in the second half of the 20th century is sufficient to demonstrate the robustness of our index for several reasons. First, the index is defensive in the sense that the time-varying component is induced only by the temperature and precipitation datasets16,17,18, which have undergone rigorous validation themselves. Second, our simple surface energy and water balance model - as proposed by Ramankutty et al.3 - relies on relatively weak assumptions and standard functional forms and thus should have almost equal applicability across several centuries. Additionally, the methodology remains widely embraced across many academic fields.

We proceed to validate our index for post-World War II periods (1961-1990 and 1971-2000), the furthest extent to which we can compare our index with other existing agricultural suitability measures. This analysis involves comparing our index to the well-established FAO GAEZ product and the static Ramankutty et al.3 index itself. First, we analyze the cross-sectional correlation and see the goodness of fit. Second, we spatially compare the differences across all grid cells. Lastly, a histogram shows that these errors are roughly symmetrically distributed.

To enable accurate comparison, all indices have been extracted to our 0.5° resolution grid covering the European landscape, specifically ranging from 25° W to 40° E and 35° N to 70° N. Since the FAO GAEZ suitability index uses climate data from 1971-2000 AD and the index built by Ramankutty et al.3 uses data from 1961-1990 AD, we average our index over these two time spans to facilitate temporal comparison.

Figure 8 (left panel), illustrates a fairly strong correlation between the agricultural suitability index derived from FAO data and our measure of agricultural suitability with an R-squared of almost 60%. Several factors contribute to this observation. Primarily, our index employs a focused approach to assessing agricultural suitability, relying on four main parameters to delineate favorable conditions. In contrast, the FAO index integrates numerous factors, including soil quality, water supply systems, and crop-specific soil suitability ratings, which contributes to its higher level of detail and reliability. Given that we do not target to fit the FAO index ex-ante and that its functional forms are quite different, we believe the observed correlation is very reassuring.

The left panel shows the correlation between the suitability index built in this study (Suit) with data averaged over the period 1971 - 2000 and a suitability index from FAO. The right panel shows the correlation between the suitability index built in this study (Suit) with data averaged over the period 1961 - 1990 and the suitability index from Ramankutty et al.3. The red dashed line represents the 45° line, and the solid red line represents the linear model y = βx. The coefficient and R2 from the linear regression are shown in the top left corner.

Figure 8 (right panel) exhibits the correlation with the index developed by Ramankutty et al.3. The achieved R-squared of over 70% is remarkably good, and it can be seen in the scatterplot that the observations line up fairly well along the 45-degree line. Our index tends to identify slightly more suitable areas. This discrepancy arises due to several differences in our methodology. Firstly, we rely on different and more recent weather and soil data, as well as incorporating a composite index of agricultural suitability from FAO instead of historical cropland cover maps for parameter calibration. Consequently, these differences impact the definition of functional forms in our index. Secondly, the limited global coverage of our temperature and precipitation data over the European landscape results in geographically more constrained observations for model training thus driving some of the observed difference. Our index is, therefore, more optimized for the European continent, whereas Ramankutty et al.3 covers the entire globe.

Figure 9 illustrates the spatial disparities between our index and the two benchmark indices, calculated as follows: difference = Suiti − Xi, where Suiti represents our measure of agricultural suitability and Xi denotes either the composite measure of agricultural suitability defined by the FAO GAEZ (left panels) or the measure of agricultural suitability by Ramankutty et al.3 (right panels) for grid i. Consequently, negative values indicate areas identified as more suitable by the other dataset, while positive values imply that our measure indicates grids with higher suitability conditions for cultivation.

Illustration of the spatial difference between suitability indices. The top panels show our measure of agricultural suitability averaged over the period 1971-2000 (as in FAO) and the period 1961-1990 (as in Ramankutty et al.3) to allow consistent temporal comparison with the two benchmark indices. The middle panels represent the composite measure of agricultural suitability from FAO GAEZ and the measure of agricultural suitability by Ramankutty et al.3. The lower panels show the spatial difference between suitability indices computed as follow: Difference = Suiti − Xi, where Suiti represents our measure of agricultural suitability (Suit1971−2000 for FAO and Suit1961−1990 for Ramankutty et al.3) and Xi denotes the benchmark indices for grid i. Consequently, negative values indicate areas identified as more suitable by the other dataset, while positive values imply that our measure indicates grids with higher suitability conditions for cultivation.

Looking at the FAO difference, we observe differences in the arid south and cold north boundaries of Europe for the FAO index, whereas our index slightly shows more suitable areas in southern Europe and along the East coast of the Adriatic Sea, most likely due to our simplified soil suitability conditions. Comparing spatial differences with Ramankutty et al.3, we still observe differences in the arid south but also note what appears to be more generally suitable areas in central Europe. As climate is unlikely to differ substantially enough in these areas to account for such differences, the variations likely result from differences in datasets on soil suitability (carbon content and soil pH), as well as induced changes in model calibration.

As a final step, we observe that these differences are minor and distributed symmetrically (Fig. 10). However, a slight shift towards the positive spectrum suggests that our index tends to identify higher suitability conditions on average in Europe for this time period, particularly when compared to the index developed by Rmankutty et al.3. It is important to emphasize that our index is not designed to compete with the precision of modern indices built by the FAO GAEZ.

The histogram shows the distribution of the differences for all 9100 grids as shown in the lower panel of Figure 9. Difference = Suiti − Xi, where Suiti represents our measure of agricultural suitability, and Xi denotes either the composite measure of agricultural suitability defined by the FAO GAEZ (FAO) or the measure of agricultural suitability by Ramankutty et al.3 for grid cell i. Consequently, negative values indicate areas identified as more suitable by the other dataset, while positive values imply that our measure indicates grids with higher suitability conditions for cultivation.

Usage Notes

The precision of our agricultural suitability index is inherently tied to the quality of its input data. Historical climate data predating the twentieth century are limited, often requiring reconstruction from documentary evidence and natural proxies, each with inherent limitations and potential biases34. Consequently, any calibration errors in the reconstruction of historical temperature and precipitation data may propagate through our model.

Our index currently offers robust estimates for the European climate due to the availability of historical data for this region. However, the scarcity of global historical data limits the model’s applicability to different climates, particularly in more arid and humid areas of the world. This could result in less reliable estimates for some regions outside of our study area.

Regarding other climatic variables essential for computing evapotranspiration rates, such as historical indices of wind speed, relative humidity, or potential sunshine hours, time-varying data are nonexistent. Our model assumes these variables remained relatively stable over past centuries. Major changes in these variables, such as sunshine hours influenced by volcanic activity, for instance, could introduce measurement errors. While this assumption simplifies the water balance model, it does mean that variations in moisture availability are primarily attributed to changes in temperature and precipitation, potentially leading to some measurement errors.

Additionally, the use of a 5-degree threshold in calculating growing degree days means that areas, where temperatures hover around this threshold, are particularly sensitive to temperature fluctuations. Researchers should interpret these results carefully, distinguishing between meaningful changes in weather conditions and potential noise.

To minimize potential errors and noise, we recommend researchers extract rasters for the specific years of interest and then use zonal averages via buffers when measuring suitability for a particular location, such as a city. This approach helps average out possible noise and measurement errors. For average suitability over larger areas, such as countries, zonal means within the relevant polygons for the given year are sufficient. For studies spanning longer periods, we suggest averaging the grid data over these years before taking zonal statistics.

If researchers are interested in agricultural suitability only in the second half of the 20th century, we recommend relying on the much more detailed products provided by the FAO cited in this text and also used for technical validation. If, however, a research project covers periods before and after the turn of the 20th century, we suggest relying on our index throughout to ensure consistency. The year 2000 is the temporal limit imposed by the historical spatial temperature and precipitation datasets.

The presented model could tremendously benefit from advances in paleoclimatology. More extensive and finer-grained paleoclimatic data extending farther back in time and geographically beyond Europe would allow to extend its scope both spatially and temporally. Arguably the most important element to achieve this would be new and expanded datasets containing geolocalized tree-ring records.

Although the model is calibrated for common European crops, combining seasonal measurements with crop-specific water, temperature, and soil requirements could yield further insights into the spatial distribution of crops and their interaction with climate. Adjusting the model for specific crop types would not just allow an understanding of their distribution but could, for example, be also informative for modern efforts to reintroduce certain indigenous crops. These potential improvements are avenues for future research. Collaborations across disciplines could significantly enhance the utility of climate data inputs, addressing diverse research needs.

Our time-varying suitability index also has the potential for being used as an input for other models dealing with changes in Europe’s historical landscape - especially when it comes to the growing interest in studying the usage and depletion of natural resources leading up to the Industrial Revolution. For example, studies examining historical deforestation patterns typically use agricultural suitability as an important input71. These datasets can potentially increase the accuracy and precision of their estimates of historical forest coverage by incorporating a time-varying suitability index.

Code availability

The computation of the index has been entirely built using R version 4.3.0 (2023-04-21 ucrt) with the following device specifications: processor 11th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-1165G7 @ 2.80GHz 2.80 GHz, installed RAM 32.0 GB (31.7 GB usable) and system type 64-bit operating system, x64-based processor.The code that generates our index is fully available on Github (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13767029) and is structured as follows:• Agricultural_Suitability.Rmd is the main replication file, setting the extent of the study, importing the raw data, processing the different parameters, constructing and saving the suitability index into a multi-layer raster: suit.tif. The file calls the following functions that have been compartmentalized for readability purposes. These scripts only define functions and do not need to be executed separately.- [fun]CRU_manipulation.R is a function that processes the raw data from the CRU58 into a list before extraction.- [fun]temp_data_manipulation.R is a function that processes the raw temperature data16,17 and stores into a list: the mean, minimum, and maximum average temperature before extraction.- [fun]pre_data_manipulation.R is a function that processes the raw precipitation data18 into a list before extraction.- [fun]evapo_grid.R is a function that computes the rate of reference evapotranspiration (ET0) using the Penman-Monteith equation following the FAO GAEZ method67.• Technical_validation.Rmd imports, compares and saves the various outputs from the technical validation part.• Figures_tables.R generates all figures and tables shown in the manuscript.• Pre_raster_generation.R imports, processes, and saves the raw precipitation data18 into multi-layer rasters for the Winter, Spring, Summer and Autumn season: precip_win.tif, precip_spr.tif, precip_sum.tif, precip_aut.tif.• Temp_raster_generation.R imports, processes, and saves the raw temperature data16,17 into multi-layer rasters for the Winter, Spring, Summer, and Autumn season: temp_win.tif, temp_spr.tif, temp_sum.tif, temp_aut.tif.

References

Dowsett, H. Speaking to the past. Scientific Data 7, 195, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-0531-6 (2020).

Lobell, D. B. & Gourdji, S. M. The Influence of Climate Change on Global Crop Productivity. Plant Physiology 160, 1686–1697, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.112.208298 (2012).

Ramankutty, N., Foley, J. A., Norman, J. & McSweeney, K. The global distribution of cultivable lands: Current patterns and sensitivity to possible climate change. Global Ecology and Biogeography 11, 377–392 (2002).

Zabel, F., Putzenlechner, B. & Mauser, W. Global Agricultural Land Resources – A High Resolution Suitability Evaluation and Its Perspectives until 2100 under Climate Change Conditions. PLoS ONE 9, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107522 (2014).

Cipolla, C. M. The Economic History of World Population (Penguin Books, Baltimore, 1962), 1 edn.

Malanima, P. Pre-Modern European Economy: One Thousand Years (10th-19th Centuries). (BRILL, Boston, NETHERLANDS, 2009).

Brooke, J. L. Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2014).

Bulliet, R., Crossley, P., Headrick, D., Hirsch, S. & Johnson, L. The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History (Cengage Learning, Australia ; Boston, MA, 2018), 7th edition edn.

Davies, N. Europe: A History. (Harper Perennial, New York, 1996).

Adams, R. M. et al. Global climate change and US agriculture. Nature 345, 219–224, https://doi.org/10.1038/345219a0 (1990).

Rosenzweig, C. & Hillel, D. Climate Change and the Global Harvest: Potential Impacts of the Greenhouse Effect on Agriculture (Oxford University Press, New York, 1998), first edition edn.

Schlenker, W., Michael Hanemann, W. & Fisher, A. C. Will U.S. Agriculture Really Benefit from Global Warming? Accounting for Irrigation in the Hedonic Approach. American Economic Review 95, 395–406, https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828053828455 (2005).

Campbell, B. M. S. The Great Transition: Climate, Disease and Society in the Late-Medieval World. 2013 Ellen Mcarthur Lectures (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Smith, C. T. An Historical Geography of Western Europe before 1800. Geographies for Advanced Study (Longman Pub Group, London, 1967), revised edn.

Kemppinen, J. et al. Microclimate, an important part of ecology and biogeography. Global Ecology and Biogeography 33, e13834, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13834 (2024). E13834 GEB-2023-0294.R2.

Luterbacher, J., Dietrich, D., Xoplaki, E., Grosjean, M. & Wanner, H. European seasonal and annual temperature variability, trends, and extremes since 1500. Science (New York, N.Y.) 303, 1499–503, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1093877 (2004).

Xoplaki, E. et al. European spring and autumn temperature variability and change of extremes over the last half millennium. Geophysical Research Letters 32, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL023424 (2005).

Pauling, A., Luterbacher, J., Casty, C. & Wanner, H. Five hundred years of gridded high-resolution precipitation reconstructions over europe and the connection to large-scale circulation. Climate Dynamics 26, 387–405, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-005-0090-8 (2006).

Cramer, W. P. & Solomon, A. M. Climatic classification and future global redistribution of agricultural land. Climate Research 3, 97–110 (1993).

Biswal, T. & Panda, R. Impact of fly ash on soil properties and productivity. Agricultural and Food Sciences, Environmental Science 11, 275–283, https://doi.org/10.30954/0974-1712.04.2018.8 (2018).

Byrt, C. S., Millar, A. H. & Munns, R. Staple crops equipped for alkaline soils. Nature Biotechnology 41, 911 – 912 (2023).

Grigg, D. B. Population Growth and Agrarian Change: An Historical Perspective. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Eng. ; New York, 1980).

Ljungqvist, F. C., Seim, A. & Huhtamaa, H. Climate and society in European history. WIREs Climate Change 12, e691, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.691 (2021).

Izdebski, A., Mordechai, L. & White, S. The Social Burden of Resilience: A Historical Perspective. Human Ecology 46, 291–303, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-018-0002-2 (2018).

Schlenker, W. & Roberts, M. J. Nonlinear temperature effects indicate severe damages to U.S. crop yields under climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, 15594–15598, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0906865106 (2009).

Goldewijk, K. K. Estimating global land use change over the past 300 years: The hyde database. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 15, 417–433, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999GB001232 (2001).

Klein Goldewijk, K., Beusen, A., Doelman, J. & Stehfest, E. Anthropogenic land use estimates for the holocene – hyde 3.2. Earth System Science Data 9, 927–953, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-9-927-2017 (2017).

Ramankutty, N. & Foley, J. A. Characterizing patterns of global land use: An analysis of global croplands data. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 12, 667–685, https://doi.org/10.1029/98GB02512 (1998).

Ramankutty, N. & Foley, J. A. Estimating historical changes in global land cover: Croplands from 1700 to 1992. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 13, 997–1027, https://doi.org/10.1029/1999GB900046 (1999).

Pongratz, J., Reick, C., Raddatz, T. & Claussen, M. A reconstruction of global agricultural areas and land cover for the last millennium. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 22, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GB003153 (2008).

Kaplan, J. O. et al. Holocene carbon emissions as a result of anthropogenic land cover change. The Holocene 21, 775–791, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683610386983 (2011).

Guinnane, T. W. We do not know the population of every country in the world for the past two thousand years. The Journal of Economic History 83, 912–938, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050723000293 (2023).

Degroot, D. et al. Towards a rigorous understanding of societal responses to climate change. Nature 591, 539–550, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03190-2 (2021).

Brázdil, R., Pfister, C., Wanner, H., Von Storch, H. & Luterbacher, J. Historical climatology in europe – the state of the art. Climatic Change 70, 363–430, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-005-5924-1 (2005).

Degroot, D. et al. The history of climate and society: a review of the influence of climate change on the human past. Environmental Research Letters 17, 103001, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac8faa (2022).

Kander, A., Malanima, P. & Warde, P. Power to the People (Princeton University Press, 2014).

Mayshar, J., Moav, O. & Pascali, L. The origin of the state: Land productivity or appropriability? Journal of Political Economy 130, 1091–1144, https://doi.org/10.1086/718372 (2022).

Henderson, V., Squires, T., Storeygard, A. & Weil, D. The Global Distribution of Economic Activity: Nature, History, and the Role of Trade. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133, 357–406, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx030 (2018).

Gollin, D., Parente, S. & Rogerson, R. The role of agriculture in development. American Economic Review 92, 160–164, https://doi.org/10.1257/000282802320189177 (2002).

Matsuyama, K. Agricultural productivity, comparative advantage, and economic growth. Journal of Economic Theory 58, 317–334, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0531(92)90057-O (1992).

Galor, O. & Özak, O. The agricultural origins of time preference. American Economic Review 106, 3064–3103, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150020 (2016).

Giuliano, P. & Nunn, N. Understanding Cultural Persistence and Change. The Review of Economic Studies 88, 1541–1581 (2020).

Zhou, X., Alysandratos, T. & Naef, M. Rice Farming and the Origins of Cooperative Behaviour. The Economic Journal 133, 2504–2532 (2023).

Schneider, J. M., Zabel, F. & Mauser, W. Global inventory of suitable, cultivable and available cropland under different scenarios and policies. Scientific Data 9, 527, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01632-8 (2022).

Akpoti, K., Kabo-bah, A. T. & Zwart, S. J. Review - agricultural land suitability analysis: State-of-the-art and outlooks for integration of climate change analysis. Agricultural Systems 173, 172–208, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2019.02.013 (2019).

Peter, B., Messina, J., Lin, Z. & Snapp, S. Crop climate suitability mapping on the cloud: a geovisualization application for sustainable agriculture. Scientific reports 10, 15487, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72384-x (2020).

Feng, L., Wang, H., Ma, X., Peng, H. & Shan, J. Modeling the current land suitability and future dynamics of global soybean cultivation under climate change scenarios. Field Crops Research 263, 108069, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108069 (2021).

Pan, Y., Yang, R., Qiu, J., Wang, J. & Wu, J. Forty-year spatio-temporal dynamics of agricultural climate suitability in china reveal shifted major crop production areas. CATENA 226, 107073, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107073 (2023).

Bradley, R. S., Briffa, K. R., Cole, J., Hughes, M. K. & Osborn, T. J. The Climate of the Last Millennium. In Alverson, K. D., Pedersen, T. F. & Bradley, R. S. (eds.) Paleoclimate, Global Change and the Future, 105–141, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-55828-3_6 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003).

Fischer, G., Velthuizen, H., Shah, M. & Nachtergaele, F. Global Agro-ecological Assessment for Agriculture in the 21st Century: Methodology and Results (International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, 2002).

FAO. Report on the expert consultation on revision of fao methodologies for crop water requirements. Land and Water Development Division, FAO, Rome, Italy (1992).

FAO & IIASA. Global Agro Ecological Zones version 4 (GAEZ v4).

Cook, E. R. et al. Old World megadroughts and pluvials during the Common Era. Science Advances 1, e1500561, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500561 (2015).

Alfani, G. & Ó Gráda, C. The timing and causes of famines in Europe. Nature Sustainability 1, 283–288, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0078-0 (2018).

Ljungqvist, F. C., Seim, A. & Collet, D. Famines in medieval and early modern Europe—Connecting climate and society. WIREs Climate Change n/a, e859, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.859 (forthcoming).

Federico, G. Feeding the World: An Economic History of Agriculture, 1800-2000. (Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 2005).

Mitchell, T. D. & Jones, P. D. An improved method of constructing a database of monthly climate observations and associated high-resolution grids. International Journal of Climatology 25 (2005).

New, M., Lister, D., Hulme, M. & Makin, I. A high-resolution data set of surface climate over global land areas. Climate Research 21, 1–25 (2002).

Wieder, W., Boehnert, J., Bonan, G. & Langseth, M. Regridded harmonized world soil database v1.2, https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1247 (2014).

Allen, R. G., Pereira, L. S., Raes, D. & Smith, M. Crop evapotranspiration - Guidelines for computing crop water requirements. FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56 15 (1998).

McMaster, G. S. & Wilhelm, W. W. Growing degree-days: One equation, two interpretations. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 87, 291–300, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1923(97)00027-0 (1997).

Cherlet, M., Hutchinson, C., Reynolds, J., Hill, S. & von Maltitz, G. World Atlas of Desertification. (Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2018).

Zomer, R. J., Xu, J. & Trabucco, A. Version 3 of the Global Aridity Index and Potential Evapotranspiration Database. Scientific Data 9, 409, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01493-1 (2022).

Abatzoglou, J., Dobrowski, S., Parks, S. & Hegewisch, K. Terraclimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Scientific Data 5, 170191, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2017.191 (2018).

Monteith, J. Evaporation and environment. Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology 19, 205–34 (1965).

Monteith, J. L. Evaporation and surface temperature. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 107, 1–27, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49710745102 (1981).

IIASA/FAO. Global agro-ecological zones (gaez v3.0). Luxemburg, Austria and FAO, Rome, Italy. (2012).

Spencer, J. Fourier series representation of the position of the sun. Search 2, 172 (1971).

Jimma, T. B. et al. Coupled impacts of soil acidification and climate change on future crop suitability in ethiopia. Sustainability 16 (2024).

Lehner, A., Philippe, D. A time-varying index for agricultural suitability across Europe from 1500–2000 Harvard Dataverse https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ECWMZS (2024).

Kaplan, J. O., Krumhardt, K. M. & Zimmermann, N. The prehistoric and preindustrial deforestation of europe. Quaternary Science Reviews 28, 3016–3034, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.09.028 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the internal seminar at the Wyss Academy for Nature at the University of Bern and two anonymous referees for their valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made equal contributions throughout all stages of the project.

Corresponding author