Abstract

The characteristics of the spatial distribution of surface soil moisture (SM) on the Qinghai‒Tibet Plateau (QTP) on a fine scale are unclear due to the lack of high-spatial-resolution SM datasets. To improve this situation, we first supplemented 659 SM datasets in areas on the QTP containing sparse monitoring stations from 2021–2022 and integrated published SM datasets. Based on Sentinel-1&2 and measured SM data, we developed an SM retrieval algorithm for the ascending and descending orbits. Then, 100-m-resolution SM spatial data were generated for the thawing season of 2017–2023 in the SAR signal-applicable area on the QTP. As validated by the measured data, the correlation coefficients of the retrieval results for the ascending and descending orbits were 0.72 and 0.69, respectively, and the bias reached 0.07 m³/m³ and an RMSE of 0.07 m³/m³ for both. These SM datasets exhibit notable promise for improving our understanding and analysis of the ecology and hydrology of different environments on the QTP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background and Summary

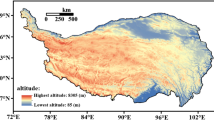

The Qinghai‒Tibet Plateau (QTP) plays a critical role in regional and global climate systems due to its unique geographical location and topographic features1,2,3. Surface soil moisture (SM), a key parameter in the process of land‒atmosphere exchange of energy and water, fulfills an essential role in the study of climate and land surface processes on the QTP4,5,6,7. In addition, variations in SM directly affect ecosystem stability and the hydrological cycle on the QTP, influencing the development of livestock husbandry. Moreover, SM in this region exhibits high spatial heterogeneity influenced by the complex topography, thus rendering relevant studies difficult. Therefore, high-spatial-resolution SM data for the QTP are urgently needed. These data can significantly enhance our ability to study the spatial and temporal distribution of soil moisture (SM) and its complex interactions with climate systems. Furthermore, it plays a crucial role in refining the accuracy of models that simulate hydrological processes such as infiltration and evapotranspiration8,9,10,11.

Currently, there are SM products produced by using retrieval algorithms, model simulations, and data assimilation techniques, such as the European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative (ESA CCI)12, Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS)13, and Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP)14, the fifth generation of the land component of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Atmospheric Reanalysis (ERA5-Land)15, and the Global Land Data Assimilation System (GLDAS)16. These products exhibit wide coverage and temporal continuity at global and continental scales, but their spatial resolutions are coarse. The SM distribution on the QTP is highly heterogeneous due to the complex topography, variable precipitation, and significant differences in altitude17,18. Currently available SM products cannot describe spatial heterogeneity and are biased in this region. Therefore, applying these SM products to ecohydrological studies on the QTP introduces uncertainties and hinders fine-scale studies19,20.

Synthetic aperture radar (SAR) technology, particularly with the advent of Sentinel-1, has provided a new data source for SM retrieval with higher spatial resolution21,22. However, acquiring high-spatial-resolution SM data across the QTP using SAR data currently faces various challenges and difficulties. First, there are few ground-based SM measurements available due to the limitations of the unique geographical conditions and accessibility. However, the training and validation of SM retrieval algorithms at the plateau scale require measured data. Second, in the frozen soil region of the QTP, the effect of soil freeze‒thaw cycles on SAR signals is significant, leading to high uncertainty in the SM retrieval results. Third, models and algorithms for SM retrieval using SAR data have been developed and widely applied on local and fine scales but are difficult to apply to the entire QTP23,24,25,26,27. Therefore, acquiring SM data with high spatial resolution and high accuracy remains challenging.

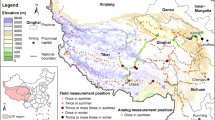

To address the above issues, our first step was to integrate measured SM datasets. In recent decades, researchers have deployed hydrological, meteorological, and permafrost monitoring stations across the QTP, partially alleviating data scarcity issues and substantially contributing to spatial SM studies28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. However, the spatial distribution of such monitoring stations is uneven, with the majority located in the Ali region, Nagqu, Maqu, Qilian Mountains (QLM), and along the Qinghai-Tibet Highway (QTH) region (Fig. 1). SM retrieval studies on the QTP have primarily focused on areas proximal to these stations, resulting in significant regional limitations in the developed algorithms36,37. Therefore, we first integrated these published datasets to obtain measured SM data for different environments on the QTP. Moreover, during the thawing season of 2021–2022, our team collected 659 SM samples across the QTP to supplement the measured dataset, and the sampling areas included the QTH region, Ali region, Qiangtang Plateau, and West Kunlun, where there are fewer monitoring stations (Fig. 1). This dataset partly resolved the scarcity of measured SM data for the QTP and could contribute to SM retrieval studies.

The thawing season (July and August) exhibits the most intense land–atmosphere energy exchange in the frozen soil region of the QTP. During this period, soil water remains in a liquid state, while during the other seasons, it exists as a combination of ice and unfrozen water38. Thus, complete SM, i.e., SM that entirely comprises liquid, can be represented by radar signals only during the thawing season39. In this study, the complete thawing season was chosen as the period for SM retrieval, which could minimize the interference of radar signals due to frozen soil and other factors and improve the sensitivity of SM to SAR signals. The acquisition of SM data during this period is important for understanding the impact of regional climate change, developing ecological conservation measures, and improving the accuracy of weather forecasting and climate modeling. In 2022, our team developed an empirical algorithm for SM retrieval using in situ SM data and Sentinel-1&2 data for a permafrost area along the QTH40. Our findings indicated that the algorithm exhibits potential applicability to frozen soil regions across the QTP.

In summary, the first objective of this study was to integrate published SM sampling data and in situ SM data for the thawing season on the QTP, aiming to facilitate the subsequent retrieval and validation of SM in this region, as well as the assessment of SM products. The second objective was to develop SM retrieval algorithms applicable to the frozen soil region of the QTP using the integrated measured SM dataset and Sentinel 1&2 data and to obtain high-spatial-resolution SM data. We hope that these high-resolution data and field sampling data can serve as a foundation for enhanced SM research on the QTP, facilitating studies on regional ecohydrology, climate change, and planning of engineering and production activities.

Methods

Experimental design

In 2022, an empirical algorithm for SM retrieval was developed by Li et al. for the permafrost areas of the QTP hinterland40. This algorithm references long-term change detection methods and utilizes seasonal backscatter differences to delineate variations in SM while reducing the impact of surface roughness. Additionally, it incorporates the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and the normalized difference moisture index (NDMI) to account for vegetation contributions. Notably, this SM retrieval algorithm has been successfully applied in the QTP hinterland, with satisfactory retrieval accuracy.

In this study, more measured SM data from diverse surface environments, along with ascending and descending Sentinel-1 data, were utilized to enhance the existing SM retrieval algorithm for obtaining spatial SM data across the entire QTP. High-spatial-resolution SM datasets were produced through three main steps, as shown in Fig. 2 dataset preparation, construction of the SM retrieval algorithm, and retrieval and postprocessing of SM data. In the subsequent sections, the data and algorithms employed in this study are detailed.

In situ data

The in situ data employed in this study were sourced from the National Tibetan Plateau Scientific Data Centre of China and were generated by Zhao et al.28, Liu et al.29,30, Yang et al.19,31, Che et al.30, Li et al.32, Zhao et al.33 and Zhang et al.34. The corresponding in situ sites span the eastern, central, western, and northeastern parts of the QTP and are characterized by different surface environments (refer to Fig. 1). The geographical coverage includes the Ali region in the western expanse of the QTP, characterized by its alpine desert landscape; the eastern Maqu region, dominated by lush alpine meadows; the QTH region and the central Nagqu region, situated within the transitional dry‒wet partition zone of the QTP; and finally, the QLM in the northeastern quadrant, notable for its complex topography and hydrothermal conditions. The elevation gradient of these stations ranges from 3033 to 5100 m above sea level, spanning approximately 2000 km from west to east. At these sites, a range of quintessential vegetation types native to the QTP can be observed, including alpine swamp meadows, alpine meadows, alpine steppes, and alpine deserts41. Details of the observation network are provided in Table 1. In this study, we performed time screening and quality control of these datasets.

From 2021 to 2022, our team collected 659 SM data points at a depth of 10 cm via the ring-knife sampling method and the time-domain reflectance method in the Ali region, along the QTH, on the Qiangtang Plateau, and in the West Kunlun region, as shown in Fig. 1. The sampling environments extended from the central to the western parts of the QTP, from alpine meadows to alpine steppes and to alpine deserts. These sampling points were located away from roads at a minimum distance of 300 m to mitigate potential anthropogenic impacts. Moreover, the selection of sampling locations prioritized relatively homogeneous ground terrain to minimize the impact of spatial heterogeneity in SM. 140 of these samples were collected on the same days as the Sentinel-1 transects, which suggests that they can be used for retrieval studies. In this study, all measured SM data were randomly divided into two parts, one for training and the other for validation. It is worth noting that the penetration depth of the Sentinel-1 C-band signal is lower than that of the in situ observations, which may lead to uncertainties in the construction and validation of the algorithm.

Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data

In 2014, a significant milestone was achieved with the successful launch of the Sentinel-1 satellite, which includes Sentinel-1A (S1A) and Sentinel-1B (S1B), as part of the Copernicus program of the ESA. S1A has an orbital period of 98.6 minutes and a revisit period of 12 days and operates in conjunction with S1B on a combined orbital cycle of 6 days. The interferometric wide (IW) imaging mode, boasting a spatial resolution of 5 m by 20 m, offers enhanced precision and better aligns with the demands of this research. In this study, the ground range detection (GRD) products of Sentinel-1 data in IW acquisition mode were utilized from the Google Earth Engine (GEE)42. Backscattered images of VV polarization over the completely thawing season (July and August) and the completely freezing season (January and February) from 2017 to 2023 were captured for SM retrieval algorithm development and validation.

Sentinel-2, launched by the European Space Agency (ESA) on June 23, 2015, carries the Multi-Spectral Instrument (MSI). The MSI sensor provides 13 spectral bands covering the visible spectrum (VIS), near-infrared (NIR), and shortwave infrared (SWIR) regions43. Sentinel-2A (S2A) offers three distinct spatial resolutions—10, 20, and 60 m—with a revisit interval of 10 days. The Sentinel-2 mission, overseen by Global Environment and Security Monitoring (GMES), employs a dual-satellite setup to frequently capture high-resolution multispectral optical observations, with global coverage of approximately 5 days44.

Auxiliary data

In this study, other SM datasets, such as ERA5-Land, GLDAS, and ESA CCI, were selected for comparison with the retrieval results. ERA5-Land, developed and maintained by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), offers a global surface dataset specifically designed to provide high-resolution surface element and meteorological variable data15. The GLDAS dataset, widely employed in the study of land surface hydrological processes, provides assimilation data from 1978 to the present16. The ESA CCI dataset represents the inaugural generation of ESA SM datasets, amalgamating active and passive microwave remote-sensing data products from across the globe12. The SMAP-1km product is a global daily surface SM dataset with 1-kilometer resolution, derived from SMAP L-band radiometer observations and downscaled using MODIS land surface temperature data through an algorithm. It has been validated against in situ SM measurements from a dense global network representing various land cover types. In 2021, Yao et al. transferred the benefits of SMAP to AMSR-E/2, and developed a global daily SSM dataset45. In 2023, Zheng et al. acquired a 1-km spatial resolution SM dataset by fusing ESA CCI products and ERA5 reanalysis dataset46. Detailed information on these datasets, along with the first layer of the depth range, is provided in Table 2. Additionally, land use type data with a spatial resolution of 10 m (ESA World Cover) were utilized for postprocessing of the retrieval results47.

Preprocessing of Sentinel-1 data

Data preprocessing and retrieval procedures were seamlessly conducted on the GEE platform, which is renowned as the world’s leading cloud-based geographic information processing system48. The GEE also provides certain preliminary data preprocessing tasks of Sentinel-1 data, facilitated through the utilization of the ESA S1 Toolbox (S1TBX)49. These tasks encompass multifaceted processes, including the integration of orbit files, mitigation of thermal noise, elimination of GRD border noise, radiometric calibration, and range-Doppler terrain correction. Furthermore, incident angle normalization, spatial filtering, and radiometric slope correction of Sentinel-1 data are needed to ensure that the data are as correct as possible.

-

(1)

Threshold masking

The very high and very low backscatter coefficients (σ°) are unlikely to carry a valid SM signal and are discarded. The threshold of σ° for the Sentinel-1 SAR image was set at -5 – -20 dB22.

-

(2)

Refined Lee filtering

Previous studies have shown that the refined Lee filter is more effective at processing SAR data than many other filtering methods50,51. Hence, the refined Lee filter with a window size of 7 × 7 was chosen to reduce the effect of anomalous signal values.

-

(3)

Sentinel-1incident angle normalization

Notably, σ° is affected by the incidence angle (θ) of Sentinel-1, resulting in a slight deviation from the actual situation. There is a certain correlation between θ and σo, which can be expressed as a slope (β). Figure 3 shows 10000 randomly selected experimental points in three strips in the eastern, central, and western parts of the study area, which are used to represent the relationship between σo and θ for the ascending and descending orbits. There is a weak negative correlation between σo and θ, with correlation coefficients of -0.16 and -0.1, respectively.

Fig. 3 The negative correlation between σo and θ for the ascending and descending data can be corrected for β52,53. In this study, the central θ value of the strip (38°) was chosen as the reference angle to reduce the overall error caused by extrapolation22. Therefore, as expressed in Eq. 1 and Eq. 2, we uniformly corrected σo to a value corresponding to an incident angle of 38° (σ(38°)).

$${\sigma }_{{\rm{asc}}}^{o}={\sigma }^{o}(\theta )+0.16\ast (\theta -38^\circ )[{\rm{dB}}].$$(1)$${\sigma }_{{\rm{desc}}}^{o}={\sigma }^{o}(\theta )+0.1\ast (\theta -38^\circ )[{\rm{dB}}].$$(2)where σoasc and σodesc denote the corrected σo values for the ascending and descending data, respectively. Equations (1) and (2) can be calculated using the GEE.

-

(4)

Radiometric slope correction

Andreas et al. provided an angular-based radial slope correction procedure on the basis of Sentinel-1 SAR images based on two physical reference models54. By extending the framework of this volume scattering model and the surface scattering model, a mask of invalid data can be generated in the active stopover region and the shadow-affected region. This method overcomes the influence of the surface environment on backscatter and improves a wide range of potential use scenarios for the GEE platform in mapping various ground parameters with Sentinel-1 on a large scale and in a rapid mode55.

Calculation and processing of optical indices

In this study, the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and normalized difference moisture index (NDMI) were used to reflect vegetation characteristics and the vegetation water content42,56,57,58. In addition, we utilized the normalized difference water index (NDWI) to identify the water bodies for removal in postprocessing59. These indices were calculated as follows:

Where ρgreen, ρred, ρnir, and ρswir are the reflection signals in the red spectrum, the green spectrum, the near-infrared spectrum, and the shortwave infrared spectrum, corresponding to the B3, B4, B8, and B11 band of Sentinel-2, respectively. The Sentinel-2 data were processed by the cloud removal function in GEE. The data from one week before and after the Sentinel-1 acquisition is selected to calculate these indices.

SM retrieval method

The SM retrieval algorithm developed based on the CD algorithm has been validated and applied in SM retrieval studies in semiarid and mountainous regions40. We characterized the changes in SM by the difference in σo (Δσo) between the thawing and freezing seasons. It can be expressed as:

Where σot is the σo value of the thawing season and σof is the σo value of the freezing season.

In this study, 1287 sets for the descending orbits and 2105 sets for the ascending orbits were collected during the thawing season from 2017 to 2023. In situ SM, Δσo, NDVI, and NDMI data were included in each set. Then, a multiple linear regression model was constructed based on the linear relationships between SM and Δσo, NDVI, and NDMI, and the SM retrieval algorithm can be expressed as follows:

where a, b, and c are the coefficients of the three variables (Δσo, NDVI, and NDMI, respectively) and d is a constant. To ensure the universality of the retrieval algorithm, we arranged the in situ data of different years together and then performed 10000 random divisions, with a ratio of nearly 8 to 2, to determine the optimal coefficient. One part was used to obtain model coefficients (a, b, c, and d). The other was used to verify the accuracy of the retrieved SM. Thus, we could obtain 10000 sets of coefficients and training and validation R2 values. Finally, we calculated the sum of R2 for the training and validation processes using their sample sizes as the weights. The optimal coefficient set was determined based on the maximum sum of the R2 values obtained from the training and validation processes.

Postprocessing of the retrieval results

Theoretically, there is a positive correlation between σo and SM, and σo during the thawing season should be greater than that in winter. Several studies have indicated significant anomalies in SM retrieval in global arid and hyperarid environments60,61,62. This phenomenon is associated with a notable bias in SM modeling and remote sensing-based estimation. Hence, in this study, the area where ∆σo is less than zero was considered abnormal and was masked during postprocessing. In addition, areas where SAR monitoring is not effective, such as water bodies and forests, were masked. The water body masks were processed by setting thresholds using the normalized difference water index (NDWI)59. ESA land use type data were used to extract forestland, inhabited land, and agricultural land to create a mask.

Data Records

The measured SM dataset has been uploaded to Figshare63. These datasets published in this study were divided into two parts, one comprising in situ monitoring data from the thawing season through quality control. The other part comprises field sampling data for 2021–2022. These data were saved in Excel, and the station data were named after the observation network with a serial number. For example, QLS-1 indicates the Qilian Mountain Observation Network No. 1 station. The sampling point data were directly named by a serial number. Some sampling sites were supplemented with environmental photographs, which are named according to the serial number of the sampling site.

These 100-m-resulotion SM datasets have been uploaded to Figshare63. According to the SM retrieval algorithms developed for both the ascending and descending orbits, users can access SM data for the frozen soil region of the QTP with a spatial resolution of up to 10 m. However, due to data storage capacity constraints, we provide 100-m-resolution SM spatial data from 2017 to 2023 for the ascending and descending orbits. For ease of use, the SM data for the thawing season are stored in GeoTIFF format, with one file for each month covering the entire QTP. Users can utilize various geographic information system (GIS) and remote sensing software packages to read and manipulate the data. The file names follow the structure of “SM_YYYY_A/D.tif”, where “SM” denotes the 100-m SM product, “YYYY” is the year, and “A/D” denotes the ascending or descending orbit.

Additionally, the algorithms and codes developed in this study are openly available for users or scholars who require SM data at the Sentinel-1 transit time or higher spatial resolution. Alternatively, users can obtain the data by contacting the authors via email (zhibinli@nuist.edu.cn) and providing details regarding the desired time frame, extent, and spatial resolution. We encourage interested parties to leverage these resources for their research and analysis purposes.

Technical Validation

Validation of the SM Retrieval Algorithm

Table 3 provides an overview of the means, standard deviations, and optimal coefficients (a, b, c, and d) derived from 10000 regressions for both the ascending and descending datasets. These regressions were conducted to validate the SM retrieval algorithm. The optimal coefficients were determined based on the regression coefficients corresponding to the maximum weighted R2 values obtained from the training and validation processes. According to Table 3, the SM retrieval algorithms for the ascending and descending orbits can be expressed as follows:

Where SMasc is the SM value retrieved by the ascending algorithm and SMdesc is the SM value retrieved by the descending algorithm. As indicated in Table 3, the mean values of the 10000 sets of regression coefficients for the ascending and descending orbit algorithms are very close to the optimal values, and the standard deviations are relatively small. This suggests that the coefficients of the two algorithms remain relatively stable and are not greatly affected by the different divisions of the training and validation samples, which indicates the robustness of the model.

In this study, 421 sets of ascending orbit data and 258 sets of descending orbit data were used to validate the retrieval algorithms. As indicated in Table 3 and Fig. 4, the retrieved results demonstrated satisfactory performance, with correlation coefficients (r) of 0.77 for the ascending algorithm and 0.71 for the descending algorithm. Additionally, the bias reached 0.07 m³/m³ and an RMSE of 0.07 m³/m³ for both algorithms, further confirming the accuracy and reliability of the retrieval process.

Generation and validation of 100-resolution SM spatial data

We mapped SM across the QTP at a 100-m resolution from 2017 to 2023 during the thawing season using Eqs. (6) and (7). The QTP spans multiple Sentinel-1 strips of both ascending and descending orbits, each characterized by different transit times. This diversity poses challenges in simultaneously acquiring SM data across the entire QTP for our study. To comprehensively assess the SM conditions across the QTP, we generated mean SM spatial data at a 100-m resolution for both the ascending and descending orbits during the thawing season from 2017 to 2023. As shown in Fig. 5, these data were validated using the mean SM across 86 monitoring stations. The r values for the ascending and descending data were 0.72 and 0.69, respectively, with a bias of 0.07 m3/m3 and an RMSE of 0.08 m3/m3 for both. Overall, the validation accuracy was satisfactory. In contrast, these spatial SM data were significantly biased low in wet regions, especially when SM exceeded 0.35 m3/m3. This indicates that our algorithm is deficient in modeling SM in wet regions, which may be related to the insufficient SM training samples in these regions.

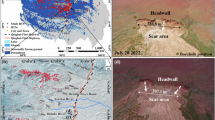

Figure 6 shows the mean SM over the thawing season in the selected years for the ascending and descending orbits. The white areas in the retrieval results are caused by postprocessing, where water bodies, mountain shadows, and anomalous areas are masked. Among them, the Karakorum region in the northwestern part of the study area encompasses more white areas because the mountain surfaces in this region comprise mostly exposed rocks. Comparing the retrieval results for these years, there was a notable decrease in SM in 2022, especially in the eastern part of the QTP. Referring to the precipitation data from the meteorological monitoring stations and ERA5-Land products, there was also a significant decrease in precipitation in the same year, thus validating the reliability of the retrieval results.

In this study, the SM retrieval results for all thawing seasons from 2017–2023 were integrated, and the multiyear thawing season mean SM was used to represent the general patterns of the SM spatial distribution on the QTP. As shown in Fig. 6, the retrieval results for the ascending and descending orbits exhibited similar SM spatial distribution patterns. The mean SM over seven years for the ascending and descending orbits were 0.141 m³/m³ and 0.135 m³/m³, respectively. The values for the descending orbits were greater than those for the ascending orbits in arid regions, such as the Ali region, Qiangtang Plateau, and Qaidam Basin.

Figure 7(a) shows the multiyear mean SM from 2017 to 2023 for the ascending and descending orbits. The average SM was 0.14 m³/m³ across the QTP during the thawing season. Overall, the spatial distribution of SM exhibited a clear pattern of decreasing from southeast to northwest. The West Kunlun region and the Qaidam Basin are the most arid, which is the result of low precipitation and a surface dominated by bare rock and Gobi. It is encouraging to note that the retrieval results could capture oasis-like areas in these regions, such as small wetlands in the valleys and small river-affected areas in the Gobi region. The Maqu region in the eastern part of the QTP is influenced by the southeast monsoon and topography, resulting in higher precipitation levels, and this region was identified as the wettest region in the retrieval results. Through an overlay of the topographic shadow map, the retrieval results demonstrated the advantages of high-spatial-resolution SM data in describing the spatial distribution of SM. For example, SM was generally higher in mountainous areas than in plains, such as foothill regions, which is consistent with field survey records. At the local scale, the retrieval results effectively captured the heterogeneity in the SM distribution on the QTP, providing detailed insights into the substantial variability due to regional climatic and topographic differences.

As shown in Fig. 7, we planned two transects, i.e., a west‒east transect and a north‒south transect, and we collected SM data from the sample plots associated with the retrieval results. The longitudinal transect clearly demonstrated the gradual increase in SM from east to west, which is generally lower in the Qiangtang Plateau region in the western part of the QTP and higher in the Maqu region in the eastern part of the QTP. The latitudinal transect more clearly demonstrated the spatial variation in SM across different topographies. SM consistently remained low in the Qaidam Basin, while it showed obvious fluctuating changes in the Kunlun Mountains and gradually increased toward the south. These changes in SM profiles are consistent with field observations, which again confirms the accuracy of these spatial SM data and their advantages in describing the spatial heterogeneity in SM.

Comparison of the SM retrievals with other SM products

Research on the applicability of SM derived from remote sensing products and reanalysis data in the QTP region has been conducted based on long-term in situ observations or sampling data in the temporal or spatial dimension at local scales, e.g., Xing, Qin, Yang, and Li20,64,65,66. The high-spatial-resolution SM data generated in this study provide new insight into the spatial distribution characteristics of SM on the QTP. This study provides a coarse comparison of the ability and accuracy of the retrieval results and six SM products (GLDAS, ERA5-Land, ESA CCI, data published by Yao et al., SMAP_1km, and data published by Zheng et al.) in describing the spatial distribution of SM in the QTP. As shown in Fig. 8, the six SM products exhibited similar SM distribution patterns on the QTP. Regarding the distribution of the regional SM value, the Qaidam Basin was the driest, followed by the Qiangtang Plateau, while the southeastern part and the southern edge of the QTP were the wettest. Referring to Fig. 7, we also extracted SM along the profile line for these SM products. The results of extraction along the latitudinal and longitudinal profiles for the six products showed that the SMAP_1km and SM product published by Zheng et al. attained the best performance in describing variations in SM but still notably lacked detailed information. The GLDAS and ESA CCI products provided accurate SM trends in the longitudinal profiles but anomalies in the latitudinal profiles. The SM data published by Yao et al. show a similar pattern to SMAP_1km, but are still limited by the coarse spatial resolution45. Notably, all datasets exhibited high bias in arid regions, indicating potential limitations in accurately characterizing the SM distribution in such environments.

To clearly demonstrate the effect of SM data with 100-m spatial resolution at the local scale, we selected three areas (Golmud, the source area of the Yangtze River, and Zhari Namco) for finer comparisons, based on field investigations (Fig. 9). The results show that coarse spatial resolution SM data products are not ideal for characterizing SM distribution at the local scale, making it difficult to integrate with field imagery for effective user interpretation. Among other SM products, the 1-km resolution product by Zheng et al. performs best, matching some wet and dry information shown in the field images. While the downscaled SM data from SMAP also have 1-km resolution, the impact of the downscaling process persists at the local scale. This emphasizes the importance of spatial resolution in accurately capturing the SM distribution. The 100-m spatial resolution SM data from this study, however, provides more detailed information, as seen in Golmud, where it reveals a relatively wet area influenced by the water system flowing north into the Qaidam Basin—something that coarse-resolution products cannot detect. In the source area of the Yangtze River, field studies show the river floodplain is mostly sandy and gravelly, with a dry surface layer, while the foothills are wetter, a pattern also reflected in the 100-m resolution data. Similarly, this high-resolution data captures the wet areas near the inlet on the western shore of Zhari Namco, as well as wetlands around the two lakes to the north. Although the SM data published by Zheng et al. and the SMAP_1km data also capture wetland information, they are far less clear than the retrieval results. These comparisons highlight the advantages of higher spatial resolution in representing SM distribution, and users can further compute SM data at even finer resolutions (down to 10 m) using the algorithms and codes provided in this study. Although retrieval results excels in spatial resolution, its temporal resolution is still inferior compared to other available products.

The mean SM during the thawing season at the monitoring network sites was overlaid on the other SM products for further comparison with the validation results shown in Fig. 5. Figure 10 shows a scatterplot of the other SM products versus the in-situ SM data for the thawing season from 2017–2021 at all sites. Among these data products, the 1-km spatial resolution SM published by Zheng et al. had the highest accuracy, with validated r, bias, and RMSE of 0.71, 0.06 m3/m3, and 0.08 m3/m3, respectively. The SMAP downscaled 1 km data also had good accuracy with r of 0.67, bias of 0.06 m3/m3, and RMSE of 0.08 m3/m3. However, the results of comparison indicate that it is also biased low. For ERA5-Land, ESA CCI, and GLDAS, the results of validation show that these data are more clustered, e.g., the SM values extracted from the ESA CCI and GLDAS data are mainly concentrated in the range of 0.2-0.3 m3/m3, and the ERA5-Land is mainly concentrated around 0.4 m3/m3. It may be related to the coarser spatial resolution of these data. The accuracy of the GLDAS product in the spatial dimension was better than that of the other two products, which is consistent with the findings for the source area of the Yangtze River64. The SM data product published by Yao et al. was developed based on SMAP and AMSR-E/245. Therefore, the validation results of the SM data product from Yao et al. were similar to SMAP, but with a slightly higher overall accuracy. In general, several SM products can describe the overall spatial distribution of SM in large-scale regions, but there are limitations and biases in the QTP. Comparing the validation results in Fig. 5 and Fig. 10 and the profile line extraction results in Fig. 7 and Fig. 8, the SM data generated in this study not only provide a high overall accuracy but also provide detailed information on the spatial distribution of SM on the QTP.

In this study, while five SM observation networks cover various regions of the QTP, the SM distribution remains uneven across the plateau. For instance, the Nagqu region encompasses numerous stations, whereas the Ali region and QLM areas exhibit limited coverage. This nonuniform distribution results in varying station densities and significant differences in the number of observed data samples. Consequently, regions with a higher station density benefit from more accurate retrieval results, whereas lower-density areas may suffer from insufficient observation data, potentially introducing biases into the findings. Therefore, expanding the observational station network and collecting field sampling data, particularly in regions with a low station density, is necessary to mitigate any biases stemming from spatial nonuniformity.

In follow-up research, several measures could enhance the accuracy of SM retrieval algorithms on the QTP. First, refinement of the long-term change detection algorithm is crucial for better capturing seasonal surface variations while considering factors such as surface roughness, snow cover, and actual surface conditions. Second, improvements in the quality of remote sensing data, including the development of algorithms to address satellite transit time differences and cloud cover issues, are essential for minimizing NDVI and NDMI estimation errors. By comprehensively implementing these measures, the accuracy of SM retrieval algorithms on the QTP could be significantly enhanced, resulting in better alignment with the unique geographical and climatic conditions of the region and providing more reliable support for both research and practical applications.

Usage Notes

In this study, we compiled 659 sets of sampling data and in situ monitoring data from 86 stations during the thawing season through temporal screening and quality control. The compiled data cover a wide range of areas, even uninhabited areas, and the data could provide references and insights for large-scale ecological and hydrological studies. In the subsequent development of SM retrieval algorithms and models, these data could be used directly as input data for training and validation. In addition, these data could be used for SM product assessment on the QTP to improve the accuracy of assessments.

We generated 100-m-resolution SM data for 2017–2023 on the QTP by using an SM retrieval algorithm, which provides higher accuracy than other SM products. Based on these data, we can more precisely characterize the spatial variability in SM on the QTP and can preliminarily and quantitatively analyze the spatial distribution of SM in different surface environments. When incorporated into models, these data can provide the necessary inputs for hydrological processes such as infiltration, runoff, and evapotranspiration, thereby greatly improving the simulation accuracy.

In addition, we developed an empirical algorithm for SM retrieval applicable to the frozen soil region of the QTP, which is very concise, understandable, and easy to implement. We integrated the algorithm and the data processing procedure into the code of the GEE and expect to publish it. The user must only select the period and study area of interest, as well as the processing procedures and retrieval algorithms for the ascending or descending orbits in the code, and high-spatial-resolution SM data (up to 10 m) can be acquired after running the program.

Code availability

The code for SM retrieval and data processing will be available at: https://gist.github.com/DrLibuyan/c8cb3a9f20d7012028af9d0a99b963f6.

References

Lin, Z. et al. Permafrost changes and its effects on hydrological processes on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 34, 1233–1246 (2019).

Immerzeel et al. Asian Water Towers: More on Monsoons–Response. Science 330, 585–585 (2010).

Cheng, G. et al. Characteristic, changes and impacts of permafrost on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Chin. Sci. Bull. 64, 2783–2795 (2019).

Crowther, T. W. et al. Quantifying global soil carbon losses in response to warming. Nature 540, 104–108 (2016).

Assouline, S. Infiltration into soils: Conceptual approaches and solutions. WRR 49, 1755–1772 (2013).

Yi, S., Wang, X., Qin, Y., Xiang, B. & Ding, Y. Responses of alpine grassland on Qinghai–Tibetan plateau to climate warming and permafrost degradation: a modeling perspective. Environ Res Lett 9, 074014 (2014).

Zeng, J. et al. Evaluation of remotely sensed and reanalysis soil moisture products over the Tibetan Plateau using in-situ observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 163, 91–110 (2015).

Zhao, T. et al. Soil moisture experiment in the Luan River supporting new satellite mission opportunities. Remote Sens. Environ. 240, 111680 (2020).

Mohanty, B. P. & Skaggs, T. Spatio-temporal evolution and time-stable characteristics of soil moisture within remote sensing footprints with varying soil, slope, and vegetation. AdWR 24, 1051–1067 (2001).

Dai, A., Trenberth, K. E. & Qian, T. A global dataset of Palmer Drought Severity Index for 1870–2002: Relationship with soil moisture and effects of surface warming. J. Hydrometeorol. 5, 1117–1130 (2004).

Hu, G. & Jia, L. Monitoring of evapotranspiration in a semi-arid inland river basin by combining microwave and optical remote sensing observations. Remote sens 7, 3056–3087 (2015).

Dorigo, W. et al. ESA CCI Soil Moisture for improved Earth system understanding: State-of-the art and future directions. Remote Sens. Environ. 203, 185–215 (2017).

Kerr, Y. H. et al. The SMOS mission: New tool for monitoring key elements ofthe global water cycle. Proc. IEEE. 98, 666–687 (2010).

Entekhabi, D. et al. The Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) Mission. Proc. IEEE. 98, 704–716 (2010).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: an improved version of the ERA5 reanalysis land component. Joint ISWG and LSA-SAF Workshop IPMA, Lisbon., 26-28 (2018).

Rodell, M. et al. The global land data assimilation system. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc. 85, 381–394 (2004).

Sun, Y., Wang, Y., Yang, W., Sun, Z. & Zhao, J. Variation in soil hydrological properties on shady and sunny slopes in the permafrost region, Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Earth Sci. 78, 1–11 (2019).

Zhang, M., Pei, W., Li, S., Lu, J. & Jin, L. Experimental and numerical analyses of the thermo-mechanical stability of an embankment with shady and sunny slopes in a permafrost region. Appl. Therm. Eng. 127, 1478–1487 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Evaluation of SMAP, SMOS, and AMSR2 soil moisture retrievals against observations from two networks on the Tibetan Plateau. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 122, 5780–5792 (2017).

Xing, Z. et al. A first assessment of satellite and reanalysis estimates of surface and root-zone soil moisture over the permafrost region of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. Environ. 265, 112666 (2021).

Tomer, S. K. et al. MAPSM: A spatio-temporal algorithm for merging soil moisture from active and passive microwave remote sensing. Remote sens 8, 990 (2016).

Bernhard et al. Toward Global Soil Moisture Monitoring With Sentinel-1: Harnessing Assets and Overcoming Obstacles. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 57, 520–539 (2019).

Kornelsen, K. C. & Coulibaly, P. Advances in soil moisture retrieval from synthetic aperture radar and hydrological applications. J. Hydrol. 476, 460–489 (2013).

Zhu, L. et al. A multi-frequency framework for soil moisture retrieval from time series radar data. Remote Sens. Environ. 235, 111433 (2019).

Wagner, W., Lemoine, G. & Rott, H. A method for estimating soil moisture from ERS scatterometer and soil data. Remote Sens. Environ. 70, 191–207 (1999).

Gao, Q., Zribi, M., Escorihuela, M. J. & Baghdadi, N. Synergetic use of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data for soil moisture mapping at 100 m resolution. Sensors. 17, 1966 (2017).

Attema, E. & Ulaby, F. T. Vegetation modeled as a water cloud. Radio Sci 13, 357–364 (1978).

Zhao, L. et al. A synthesis dataset of permafrost thermal state for the Qinghai–Tibet (Xizang) Plateau, China. Earth Syst Sci Data. 13, 4207–4218 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. The Heihe Integrated Observatory Network: A basin‐scale land surface processes observatory in China. Vadose Zone J. 17, 1–21 (2018).

Che, T., Li, X., Liu, S., Li, H. & Yang, X. Integrated hydrometeorological, snow and frozen-ground observations in the alpine region of the Heihe River Basin, China. Earth System Science Data. 11, 1483–1499 (2019).

Yang et al. A Multiscale Soil Moisture and Freeze-Thaw Monitoring Network on the Third Pole. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1907–1916 (2013).

Li, X. et al. Qinghai Lake Basin Critical Zone Observatory on the Qinghai‐Tibet Plateau. Vadose Zone J. 17, 1–11 (2018).

Zhao Changming, Z. R. Qilian Mountains integrated observatory network: cold and arid research network of Lanzhou university (an observation system of meteorological elements gradient of Xiyinghe station, 2018). N. T. P. T. P. E. D. Center National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center (2019).

Zhang, P. et al. Status of the Tibetan Plateau observatory (Tibet-Obs) and a 10-year (2009–2019) surface soil moisture dataset. Earth Syst Sci Data. 13, 3075–3102 (2021).

Yang, K. et al. A multiscale soil moisture and freeze–thaw monitoring network on the third pole. Bull. Amer. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1907–1916 (2013).

Yang, M. et al. Soil moisture retrievals using multi-temporal sentinel-1 data over nagqu region of tibetan plateau. Remote Sensing. 13, 1913 (2021).

Xiaojing, B. et al. First Assessment of Sentinel-1A Data for Surface Soil Moisture Estimations Using a Coupled Water Cloud Model and Advanced Integral Equation Model over the Tibetan Plateau. Remote sens. 9, 714 (2017).

Zhao, L., Cheng, G., Li, S., Zhao, X. & Wang, S. Thawing and freezing processes of active layer in Wudaoliang region of Tibetan Plateau. Chin. Sci. Bull. 45, 2181–2187 (2000).

Xu, L., Abbaszadeh, P., Moradkhani, H., Chen, N. & Zhang, X. Continental drought monitoring using satellite soil moisture, data assimilation and an integrated drought index. Remote Sens. Environ. 250, 112028 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Retrieving Soil Moisture in the Permafrost Environment by Sentinel-1/2 Temporal Data on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Remote sens. 14, 5966 (2022).

Wang, Z.-w. et al. Mapping the vegetation distribution of the permafrost zone on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Mountain Sci. 13, 1035–1046 (2016).

Zeng, X., Xing, Y., Shan, W., Zhang, Y. & Wang, C. Soil water content retrieval based on Sentinel-1A and Landsat 8 image for Bei’an-Heihe Expressway. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 25, 118–126 (2017).

Drusch, M. et al. Sentinel-2: ESA’s optical high-resolution mission for GMES operational services. Remote Sens. Environ. 120, 25–36 (2012).

Li, J. & Roy, D. P. A global analysis of Sentinel-2A, Sentinel-2B and Landsat-8 data revisit intervals and implications for terrestrial monitoring. Remote sens. 9, 902 (2017).

Yao, P. et al. A long term global daily soil moisture dataset derived from AMSR-E and AMSR2 (2002–2019). Scientific data. 8, 143 (2021).

Zheng, C., Jia, L. & Zhao, T. A 21-year dataset (2000–2020) of gap-free global daily surface soil moisture at 1-km grid resolution. Scientific Data. 10, 139 (2023).

Zanaga, D. et al. ESA WorldCover 10 m 2021 v200. (2022).

Gorelick, N. et al. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 202, 18–27 (2017).

Veci, L., Lu, J., Foumelis, M., Engdahl, M., in EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts. pp. 19398 (2017).

Lee, J.-S., Grunes, M. R. & De Grandi, G. Polarimetric SAR speckle filtering and its implication for classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 37, 2363–2373 (1999).

He, L. et al. Soil moisture retrieval using multi-temporal Sentinel-1 SAR data in agricultural areas. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 32, 142–148 (2016).

Baghdadi, N., Zribi, M., Loumagne, C., Ansart, P. & Anguela, T. P. Analysis of TerraSAR-X data and their sensitivity to soil surface parameters over bare agricultural fields. Remote Sens. Environ. 112, 4370–4379 (2008).

Pathe, C., Wagner, W., Sabel, D., Doubkova, M. & Basara, J. B. Using ENVISAT ASAR global mode data for surface soil moisture retrieval over Oklahoma. USA. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 47, 468–480 (2009).

Hoekman, D. H. & Reiche, J. Multi-model radiometric slope correction of SAR images of complex terrain using a two-stage semi-empirical approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 156, 1–10 (2015).

Vollrath, A., Mullissa, A. & Reiche, J. Angular-based radiometric slope correction for Sentinel-1 on google earth engine. Remote sens. 12, 1867 (2020).

Bao, Y., Lin, L., Wu, S., Deng, K. A. K. & Petropoulos, G. P. Surface soil moisture retrievals over partially vegetated areas from the synergy of Sentinel-1 and Landsat 8 data using a modified water-cloud model. International journal of applied earth observation geoinformation 72, 76–85 (2018).

El Hajj, M. et al. Soil moisture retrieval over irrigated grassland using X-band SAR data. Remote Sens. Environ. 176, 202–218 (2016).

Gao, B., NDWI-a normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Remote Sens. Environ. 58 (1996).

McFeeters, S. K. The use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 17, 1425–1432 (1996).

Ullmann, T. et al. Exploring Sentinel-1 backscatter time series over the Atacama Desert (Chile) for seasonal dynamics of surface soil moisture. Remote Sens. Environ. 285, 113413 (2023).

Wagner, W. et al. Widespread occurrence of anomalous C-band backscatter signals in arid environments caused by subsurface scattering. Remote Sens. Environ. 276, 113025 (2022).

Morrison, K. & Wagner, W. Explaining anomalies in SAR and scatterometer soil moisture retrievals from dry soils with subsurface scattering. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 58, 2190–2197 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. 100-m-resolution surface soil moisture data during the thawing season on the Qinghai‒Tibet Plateau. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27239613 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Analysis of soil moisture content in the active layer in the permafrost region of the Tuotuo River source in frozen season. J. Glaciolo. Geocryol. 44, 56–68 (2022).

Yang, S., Li, R., Wu, T., Hu, G. & Qiao, Y. Evaluation of reanalysis soil temperature and soil moisture products in permafrost regions on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Geoderma. 377, 114583 (2020).

Qin, Y. et al. Assessment of reanalysis soil moisture products in the permafrost regions of the central of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. HyPr. (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (2019QZKK0201), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41931180, 42376254).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhibin Li: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing – original draft. writing—review and editing. Lin Zhao: conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing. Lingxiao Wang: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing. Guangyue Liu: data curation, investigation, writing—review and editing. Erji Du: methodology, data curation, investigation. Defu Zou: methodology, conceptualization. Guojie Hu: methodology, writing—review and editing. Luhui Yin: data curation, investigation. Chong Wang: data curation, writing—review and editing. Zanpin Xing: methodology, formal analysis, validation. Shibo Liu: data curation, investigation. Minxuan Xiao: data curation, investigation. Yiwei Wang: data curation, investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest for this article. The funding agencies had no role in the design of the study, the data processing and writing or in the decision to publish the results.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Zhao, L., Wang, L. et al. 100-m-resolution surface soil moisture data during the thawing season on the Qinghai‒Tibet Plateau. Sci Data 12, 497 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04831-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04831-1