Abstract

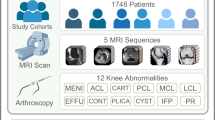

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become a standard examination method for the knee, facilitating the identification of a range of knee-related issues, including injuries, arthritis, and other conditions. The lengthy image acquisition time inherent to MRI results in the generation of motion artifacts, which in turn impairs the efficiency of MRI applications. To address this challenge, we present a multi-view, multi-sequence knee joint paired MRI dataset (image with motion artifact vs. Ground Truth obtained after rescanning), named Knee MRI for Artifact Removal (KMAR)-50K, which includes 1,190 patients, 1,444 pairs of MRI sequences, and 62,506 scan images. The dataset comprises images of anonymous paired NIfTI files that have undergone bias field correction, maximum minimum normalization, and paired image spatial registration in sequence. The objective of our data-sharing program is to facilitate the benchmark testing of methods of knee MRI motion artifact removal. Benchmarking three models revealed U-Net’s superior transverse plane performance (PSNR = 28.468, SSIM = 0.927) with fastest inference (0.5 s/volume), highlighting its clinical value in accuracy-efficiency balance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is a non-invasive imaging method, which has been widely applied in clinical practice1. Compared to X-ray and computerized tomography (CT), MRI stands out for its high spatial resolution, excellent soft tissue contrast, and lack of radiation2. It enables accurate examination of soft tissue structures such as ligaments and menisci of the knee, showcasing advantages such as a high detection rate, low misdiagnosis rate, and high specificity. Consequently, MRI has become the standard imaging modality for assessing the knee joint disorders and provides valuable support for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of knee joint diseases3,4.

Due to its prolonged image acquisition period, MRI is more prone to motion artifacts in comparison to other imaging modalities, such as CT and ultrasound5. Although rescanning can to some extent reduce the impact of motion artifacts, it also results in a greater investment of valuable machine time, which ultimately diminishes clinical efficiency. Moreover, in specific clinical scenarios, such as with infants, patients experiencing involuntary tremors, individuals with traumatic injuries, and those in pain, a repeated scan may not necessarily yield clear images. Consequently, images with motion artifacts have the potential to impede accurate diagnosis by physicians, which could result in misdiagnosis. This has the effect of undermining the applicability of MRI technology. Therefore, effectively overcoming motion artifacts caused by movement is one of the key areas of research in the field of magnetic resonance technology.

Despite the advent of several proposed techniques aimed at preventing, mitigating, and correcting motion artifacts, including physically restricting patient movement6,7, advanced sampling techniques8,9,10, faster imaging sequences11,12, and the implementation of some prospective13,14 and retrospective correction methods15,16,17, motion correction remains an evolving field. It is not feasible to eliminate motion artifacts by applying a single method5.

At present, numerous retrospective artifact correction techniques are based on deep learning methodologies18,19,20, which frequently necessitate a substantial quantity of paired artifact and artifact-free image data to substantiate their efficacy. It is noteworthy that there are existing public knee MRI image datasets, such as fastMRI21, MRNet22, and kneeMRI23, whose primary focus is on utilizing machine learning models to aid in diagnosis instead of artifact removal. Although the fastMRI project incorporates certain aspects of image reconstruction, its principal objective is to expedite the MRI process. These publicly available databases have an obvious limitation: the absence of critical paired image data, namely knee MRI images with motion artifacts and without artifacts after rescanning from the same patient. In light of this, the importance of our dataset comes to the fore, as it provides paired data not provided in the aforementioned datasets and fills a gap in the field of image quality improvement of knee MRI.

In this study, we propose KMAR-50K dataset, which includes 1,444 pairs of knee joint scans from 1,190 patients, for a total of 62,506 slices. These images are from two different machines with field strengths of 3.0 T and 1.5 T, respectively, ensuring the diversity and breadth of the data. The dataset includes the mostly frequently and routinely used MRI sequences in medical diagnosis: Proton Density-weighted Turbo Spin Echo (PD-TSE), Proton Density-weighted Fast Spin Echo (PD-FSE), T1-weighted Turbo Spin Echo (T1-TSE), T1-weighted Fast Spin Echo (T1-FSE), T2-weighted Turbo Spin Echo (T2-TSE), and T2-weighted Fast Spin Echo (T2-FSE). Moreover, we registered the corresponding paired images from the coronal, sagittal, and transverse planes, respectively, which allows for more precise adjustment of image accuracy and benefits the generalization ability of deep learning models.

In summary, this dataset is highly comprehensive in terms of size, device source, and sequence type for paired data. It went thorough quality control for inclusion and professional scoring by experienced radiologists. It is represented in a ready-to-use format. In addition, its usability was validated by three commonly used models and their results of artifact removal can be compared using Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), structural similarity index matric (SSIM), and error metrics. Benchmark validation across validation and independent testing cohorts revealed U-Net’s consistent superiority, achieving peak transverse-plane performance (PSNR = 28.683, 28.468, SSIM = 0.933, 0.927) with 0.5 s/volume inference speed – 18 times faster than Enhanced Deep Residual Networks for Single Image Super-Solution (EDSR) while maintaining <0.06 in 3 error metrics across all anatomical planes. The standardized paired data structure facilitates direct comparison of artifact removal methods, establishing KMAR-50K as a foundational resource for developing clinically deployable MRI reconstruction solutions.

Methods

This section provides a comprehensive account of the sources and processing procedures utilized in the provided dataset (Fig. 1). In order to prove the usability of the dataset for the purpose of motion artifact removal, we have presented a detailed introduction to three categories of frequently-used image motion-artifact removal models, accompanied by an evaluation of the models and the results they generate (Fig. 2).

Study flowchart of the enrolled patients. Non-motion artifacts include fold over artifacts, vascular pulsation artifacts and metal artifacts. Other problems include inconsistencies in scope before and after rescanning, changes in PD sequence parameters, uneven magnetic fields, etc. Failing to meet data processing criteria include missing frames, inconsistencies before and after rescanning. Roughly divided into training cohort and validation cohort by a ratio of approximately 9:1. Additionally, an independent testing cohort was collected for model evaluation.

Workflow of this study. This study was conducted in five steps. Firstly, pairs of ground truth images and noise images were collected for a total of 1,104 patients (1,341 pairs of MR images). Subsequently, the ground truth and noise images were subjected to preprocessing, including N4 bias field correction, normalization and image registration. Thirdly, the de-artifact model was trained based on the pre-processed images of 90% of the patients. The network included in this study comprised DDPM (Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models), EDSR (Enhanced Deep Residual Networks for Single Image Super-Resolution) and U-Net. Fourthly, the performance of models were evaluated in the remaining 10% of patients and independent testing cohort by comparing the difference between the generated image and the pre-processed ground truth images. Furthermore, subgroup analyses were conducted to assess the performance of images with varying axes.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (Approval No. (Research) 3, 2024). The committee granted a waiver of informed consent for the following reasons:

-

(1)

This is a retrospective study using previously acquired clinical imaging data;

-

(2)

All personal identifiers and protected health information were completely removed from the DICOM files and associated data;

-

(3)

The research involves no more than minimal risk to participants.

The ethics committee explicitly approved the open publication of this fully anonymized dataset. All DICOM tags containing personal information (including patient names, IDs, birth dates, and examination dates) were systematically removed prior to data sharing.

KMAR-50K dataset

The multi-parametric knee MRI dataset of this study comprises 1,190 patients who underwent knee joint scans twice, providing images with motion artifact and ground truth images without artifact (after rescanning while staying in that scanner). The imaging data was acquired in three different views: coronal, sagittal, and transverse. The following three data sources are provided:

-

(1)

Anonymous but unprocessed data: these data from two field strengths (1.5 T and 3.0 T), with a layer thickness range of 3 mm to 5 mm, and a median thickness of 3.5 mm. It includes six sequences: PD-TSE, PD-FSE, T1-TSE, T1-FSE, T2-FSE, and T2-TSE.

-

(2)

Preprocessed data: Images generated after N4 bias field correction and maximum minimum normalization for both artifact and ground-truth images. In addition, this dataset also provides ground-truth images mapped to the artifact images by spatial registration.

-

(3)

Radiologist’s subjective scoring data: In evaluating the artifact and ground truth images, junior and senior radiologists conducted subjective assessments, including the degree of artifact, target structure, and overall image quality. Each of the three indicators was scored on a five-point scale, with higher scores indicating lower severity of image artifacts, superior diagnostic ability of target structures, and higher overall image quality.

Image acquisition

The MRI scan was obtained from two manufacturers - Siemens (87.0% for Aera 1.5 T, 11.8% for Verio 3.0 T) and Alltech Medical Systems (1.2%) at the Department of Radiology, Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital, Chengdu, China. The quartiles of slice thickness (unit: mm) are 3.5 (3.5~4.0) and 3.5 (3~5.0), respectively. The specific parameters are shown in the Table 1.

Image inclusion

The study initially included 330, 445, 439 and 86 patients who underwent knee MRI at Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital from 2020 to 2023, resulting in a total of 1,300 cases. In 51 cases, non-motion artifacts were excluded. In 57 cases, other problems were identified, including inconsistent ranges before and after rescanning, altered PD sequence parameters, magnetic field inhomogeneity, and so forth. Two additional cases were excluded due to missing frames and inconsistencies before and after rescanning. These exclusions resulted in a total of 110 cases being excluded from further analysis. Ultimately, a total of 1,104 patients were included in the study from 2020 to 2022, which were randomly divided into a training cohort (n = 994) and a validation cohort (n = 110) in a ratio of 9:124. Patients starting from 2023 were included as an independent testing cohort (n = 86). This partitioning strategy is designed to provide the model with sufficient data for generalization while also ensuring an unbiased evaluation of its performance. The process flowchart is shown in Fig. 1.

Scanning image quality evaluation

A junior and a senior radiologist independently evaluated the quality of the images before and after rescanning. The criteria and basis for scoring the degree of artifact, target structure, and overall image quality are shown in Table 2. All features were evaluated using a 5-point scale, with lower scores indicating the presence of liger artifacts, less obvious target structures, and poorer image quality. Higher scores indicate superior image quality, which can be utilized for clinical diagnosis. The intra-class correlation (ICC) method was employed to assess the inter-observer agreement in the evaluation of two radiologists25.

Pre-processing and quality control

Image preprocessing consists of the following steps: (1) The raw DICOM files were sorted by sequence and converted to NIfTI format; (2) All images underwent N4 bias field correction in order to eliminate intensity inhomogeneity correction of MR images26; (3) The adaptive normalizer was employed to remove voxels with MR image intensity values exceeding 95% and falling below 5%27; (4) Max-min Normalization was employed to standardize the image intensity values between 0 and 1; (5) By employing the motion artifact image as a fixed image and leveraging the synchronous normalization algorithm of the Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) toolkit28, which is a form of intensity-based image registration, the ground truth image is mapped onto a fixed image. This process achieves spatial alignment of paired images, ensuring that subsequent analyses account for any spatial variations introduced by motion artifacts.

Model construction

In order to investigate the efficacy of different baseline models for the removal of motion artifacts, this study explored three frequently used baseline models on the KMAR-50K dataset.

-

(1)

DDPM: The Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM) is introduced and developed in the work of Jonathan Ho29, which are essential probabilistic models for generating data distributions gradually. In particular, the forward diffusion process defines an operation where the data structure is gradually destroyed, for example, by corrupting it with noise30. The reverse diffusion process is an iterative de-noising method whereby a U-Net is trained to model a target distribution, gradually recovering the ground truth image data structure.

-

(2)

EDSR: The Enhanced Deep Residual Networks for Single Image Super-Solution (EDSR) model represents an advanced deep learning framework that has been specifically designed for the purpose of single image super-resolution reconstruction. The EDSR model was proposed by Ming Hui Zhang et al. and effectively addresses the issues of blur and artifacts present in traditional super-resolution methods through the use of a Residual in Residual structure31. This model is capable of generating high-quality, high-resolution images by learning the mapping relationship between low-resolution and high-resolution images.

-

(3)

U-Net: We have implemented novel enhancements to the EDSR model by substituting the initial deep residual network configuration with the widely acknowledged U-Net architectural framework. The U-Net, as proposed by Ronneberger et al., is an efficient convolutional neural network that achieves super-resolution reconstruction of images through an encoder-decoder structure32. The primary advantage of U-Net is its symmetrical network design, which enables the network to capture comprehensive feature information during the encoding phase and accurately restore the details of high-resolution images during the decoding phase.

The three models above were trained in a computing environment equipped with a NVIDIA A40 GPU, thereby achieving dual improvements in image quality and resolution. The input for model training is uniformly a cropping size of 256 × 256 pixels, which simulate an imaging spacing of 0.5 × 0.5. This ensures consistency and comparability of the input data. During the training process, the EDSR and U-Net models were further enhanced in their ability to generalize through the utilization of data augmentation techniques, including shift, rotation, and flip, which enabled the simulation of various image deformations that may be encountered in practical applications. To ensure precise optimization of the predictive performance of the models, all three models employ the L1 loss function, which enhances the accuracy of reconstructed images by minimizing the absolute error between the predicted results and the ground truth images. Additionally, the Adam optimizer was selected, as it is an adaptive learning rate optimization algorithm that can effectively adjust the learning rate and accelerate the learning process of the model. The experimental environment is based on Python 3.7.13 and utilizes Torch 1.13.1 and torch-vision 0.14.1 libraries, which provide robust support for these models.

Evaluation methods

This study employed six key indicators to evaluate image quality, which are categorized into three distinct groups: similarity, error, and signal-to-noise ratio metrics. The similarity metrics include the structural similarity index matric (SSIM) and normalized cross-correlation (NCC)33, which evaluate the structural and correlation similarities between images. The error metrics consist of the mean absolute error (MAE)34, normalized root mean square error (NRMSE)35 and L1 loss, which quantify the discrepancies between predicted and actual values. Additionally, the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) is employed as a signal-to-noise ratio metric, reflecting the image’s contrast and the efficacy of noise suppression. A variance analysis was conducted to identify significant performance differences among the models. Additionally, subgroup analyses were performed for transverse, sagittal, and coronal view to evaluate the impact of direction on image quality. Computational efficiency was also compared, encompassing parameters, floating point operations (FLOPS), memory, convolutional layers, maximum stride, and forward time. This provides a comprehensive reference for model selection and evaluation.

Data Records

The dataset is publicly available via Mendeley Data repositories36: Repository 1 (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/xw7mrg7ntg) and Repository 2 (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/95w9f5tzz8)37.

The Training Cohort (1,341 sequences from 1,104 patients) is stored in folders ArtifactData_part1, GroundTruthData_part1 (Repository 1) and ArtifactData_part2, GroundTruthData_part2 (Repository 2), while the Independent Testing Cohort (103 sequences from 83 patients) is in folders Testing_ArtifactData (Repository 2) and Testing_GroundTruthData (Repository 1). All files are in NIfTI format (.nii.gz), with filenames denoting processing stages: “N4” indicates N4 bias field correction, “Norm” signifies subsequent intensity normalization, and “SegSyN” (exclusive to ground truth folders) denotes ground truth images registered to artifact space via SyN algorithm of ANTs (https://antspy.readthedocs.io).

Metadata tables include TrainingCohort.csv and TestingCohort.csv, with columns: Patient (ID format: Year_Order_Direction_SeriesNumber, matching filenames), StudyDate, SeriesDescription, MagneticFieldStrength, SequenceName, RepetitionTime, EchoTime, FlipAngle, SliceThickness, PixelSpacing, Manufacturer, ManufacturerModel.

Technical Validation

Subject characteristics

The data set was derived from 1,190 patients who underwent knee scans, with a total of 1,444 pairs of MRI sequences (Table 3) in training, validation and independent testing cohort. The population consisted of 558 males (47%) and 632 females (53%), with a median age of 46 years (quartile range: 18–83 years). The PD-TSE, T1-TSE, and T2-TSE accounted for 82.83% (n = 1,196), 16.00% (n = 231), and 1.17% (n = 17), respectively. The distribution of sequences across the transverse, sagittal, and coronal planes was as follows: 34% (n = 492), 31% (n = 441), and 35% (n = 511), respectively.

Consistency analysis of subjective evaluation of scanned images

The inter-rater reliability for the degree of artifacts, target structure display, and overall image quality was strong. The ICC results demonstrated that both radiologists assigned a score of 2 (1~3) to the degree of artifacts in the first scan, with an ICC value of 0.882 (0.866~0.895). Following the rescanning, the distribution of artifact degree scores shifted to 5 (4~5), with an ICC value of 0.871 (0.855~0.886). Similarly, the target structure score distribution after the first scan and rescans was 2 (2~3) and 4 (3~4), with ICC values of 0.837 (0.816~0.856) and 0.869 (0.852~0.884), respectively. The overall quality of the image after the first scan and the rescan was rated 2 (1~2) and 4 (3~4), respectively. The radiologists score consistency was 0.864 (0.847~0.88) and 0.891 (0.877~0.903), respectively. The average scores of the rescanned images were found to be significantly higher than those of the first scanned images for all three of these metrics (paired Wilcox-test, p < 0.001).

Motion artifacts removal performance of different models

The evaluation results of three different motion artifact removal models are presented in Table 4 and Fig. 3. In the independent testing cohort, the ESDR method exhibited the most optimal performance in terms of PSNR and NRSME, with average values of 27.704 and 0.046, respectively. With regard to SSIM, NCC, MSA, and L1 Loss, the U-Net demonstrated the most optimal performance, with average values of 0.921, 0.979, 0.011 and 0.026, respectively. The subgroup analysis of transverse, sagittal and coronal images revealed that the performance of transverse images was superior, whereas that of sagittal images was the least effective. Figure 4 illustrates the comparison of generated images and ground truth for three instances under different models. While the ESDR and U-Net excel in specific metrics, their performance trade-offs suggest that no single method universally addresses all aspects of motion artifact removal. The persistent underperformance on sagittal images across all models may indicate inherent challenges in capturing anisotropic motion patterns or limited representation of sagittal-plane artifacts in training data.

Raincloud plot of each matrix on different models in testing cohort. The larger the three indicators, PSNR, SSIM, and NCC (the first row), the superior the model performance. Conversely, the smaller the NRSME, MSA, and L1 Loss (the second row), the more optimal the result. The dots represent the testing samples. The width of the violin plot represents the concentration trend of the various matrices under consideration. In a box-and-whisker plot, the box represents the inter-quartile range (IOR), the central line represents the median, the whisker boundaries extend to a distance of 1.5 IOR, and points outside the whisker boundaries represent outliers.

The de-motion-artifact results of various algorithms are compared in three subjects with different axial views. The image input to the model was preprocessed. In DDPM, EDSR and U-Net models, the PSNR values for the subject 1 (the first row) were 30.80, 27.11 and 31.91, while the SSIM values were 0.93, 0.92 and 0.96. The corresponding values for the subjects 2 (the second row) and 3 (the third row) were 26.93, 22.737, 28.66 and 0.91, 0.84, 0.95; 28.62, 25.63, 30.72 and 0.95, 0.91, 0.97.

Comparison results of different models

According to ANOVA test, there were statistically significant differences among the DDPM, EDSR and U-Net with regard to the six evaluation metrics (all p < 0.001). A pairwise comparison of the models using a paired t-test or a paired Wilcoxon test revealed that the EDSR exhibited significantly superior performance compared to the DDPM and U-Net for the PSNR metric (p < 0.001). Conversely, the U-Net demonstrated significantly enhanced performance compared to the DDPM and EDSR for the SSIM, NCC, NRMSE, MSA and L1 loss (all p < 0.001). The results of the subgroup analyses of the three views were found to be consistent. Subgroup analyses (transverse, sagittal, and coronal) yielded consistent results.

A comparative analysis was conducted on the parameters, memory consumption, FLOPS, forward time (average of 132 experiments from validation cohort conducted on NVIDIA A40), number of convolutional layers, and maximum stride of different networks. In comparison to DDPM, U-Net exhibits a markedly reduced parameter count (17.3 M), memory consumption (11.41MB), FLOPs (39991), and convolutional layers (20). In contrast to EDSR, the forward time has been observed to decrease from 9 s to 0.5 s (for further details, please refer to Table 5). The computational efficiency of U-Net (0.5 seconds inference time) comes at the cost of a lower PSNR, while the high accuracy of ESDR requires 18 times the computational time of U-Net, limiting its real-time clinical applicability. While DDPM’s 3315-second inference time is clinically impractical, its visually plausible motion artifact removal motivates future work on accelerated diffusion models (e.g., latent diffusion) to reduce computational costs while preserving perceptual fidelity.

Limits of the dataset

Our dataset has several limitations. Firstly, the dataset is constrained by its single-center retrospective design, which may not fully encompass the diversity of practices and patient demographics across different centers. Secondly, the overwhelming majority of the data in the dataset (98.9%) originates from Siemens scanners, which introduces vendor-specific biases that may impact the generalizability of our results on other manufacturer platforms. Additionally, the data from the 1.5 T scanner (88%) is markedly larger than that from 3.0 T and higher field strengths, indicating that our method may not be fully evaluated under a more diverse range of imaging conditions. Moreover, the retrospective nature of our study may introduce selection bias, which may not accurately reflect the characteristics of a more inclusive patient population.

Code availability

In this study, U-Net is available at https://github.com/milesial/Pytorch-UNet, EDSR can be assessed at https://github.com/yulunzhang/EDSR-PyTorch, and DDPM can be found at https://gitcode.com/gh_mirrors/me/med-seg-diff-pytorch. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of these open-source projects and encourage readers to consult the respective repositories for detailed implementation and usage instructions.

References

Carr, M. W. & Grey, M. L. Magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Nurs 102, https://doi.org/10.1097/00000446-200212000-00012 (2002).

Kijowski, R. A.-O. & Fritz, J. Emerging Technology in Musculoskeletal MRI and CT. Radiology 306, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.220634 (2023).

Del Grande, F. et al. Five-Minute Five-Sequence Knee MRI Using Combined Simultaneous Multislice and Parallel Imaging Acceleration: Comparison with 10-Minute Parallel Imaging Knee MRI. Radiology 299, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2021203655 (2021).

Chalian, M. A.-O. et al. The QIBA Profile for MRI-based Compositional Imaging of Knee Cartilage. Radiology 301, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2021204587 (2021).

Spieker, V. et al. Deep Learning for Retrospective Motion Correction in MRI: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 43, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2023.3323215 (2024).

McClelland, J. R. et al. Respiratory motion models: a review. Med Image Anal 17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2012.09.005 (2013).

Ringe, K. A.-O. X. & Yoon, J. A.-O. Strategies and Techniques for Liver Magnetic Resonance Imaging: New and Pending Applications for Routine Clinical Practice. Korean J Radiol 24, https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2022.0838 (2023).

Sander, J., de Vos, B. D. & Išgum, I. Autoencoding low-resolution MRI for semantically smooth interpolation of anisotropic MRI. Med Image Anal 78, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2022.102393 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. Fast Multi-Contrast MRI Acquisition by Optimal Sampling of Information Complementary to Pre-Acquired MRI Contrast. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 42, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2022.3227262 (2023).

Lei, P. et al. Joint Under-Sampling Pattern and Dual-Domain Reconstruction for Accelerating Multi-Contrast MRI. IEEE Trans Image Process 33, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2024.3445729 (2024).

Friedrich, M. A.-O. Steps and Leaps on the Path toward Simpler and Faster Cardiac MRI Scanning. Radiology 298, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2021204084 (2021).

Haldar J. P. & Setsompop, K. Linear Predictability in MRI Reconstruction: Leveraging Shift-Invariant Fourier Structure for Faster and Better Imaging. IEEE Signal Process Mag 37, https://doi.org/10.1109/msp.2019.2949570 (2020).

Pietsch, M., Christiaens, D., Hajnal, J. V. & Tournier, J. D. dStripe: Slice artifact correction in diffusion MRI via constrained neural network. Med Image Anal 74, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2021.102255 (2021).

An, H. J. et al. MRI-Based Attenuation Correction for PET/MRI Using Multiphase Level-Set Method. J Nucl Med 57, https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.115.163550 (2016).

Klodowski, K. A.-O., Sengupta, A., Dragonu, I. & Rodgers, C. A.-O. Prospective 3D Fat Navigator (FatNav) motion correction for 7T Terra MRI. NMR Biomed 38, https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.5283 (2024).

Hewlett, M. A.-O. X., Oran, O. A.-O., Liu, J. A.-O. & Drangova, M. A.-O. Prospective motion correction for brain MRI using spherical navigators. Magn Reson Med 91, https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.29961 (2024).

Ariyurek, C. A.-O., Wallace, T. A.-O., Kober, T. A.-O., Kurugol, S. A.-O. & Afacan, O. A.-O. Prospective motion correction in kidney MRI using FID navigators. Magn Reson Med 89, https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.29424 (2023).

Zheng, S. et al. A Deep Learning Method for Motion Artifact Correction in Intravascular Photoacoustic Image Sequence. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 42, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2022.3202910 (2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. Sinogram domain metal artifact correction of CT via deep learning. Comput Biol Med 155, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.106710 (2023).

Luo, L. et al. Scale-Aware Super-Resolution Network With Dual Affinity Learning for Lesion Segmentation From Medical Images. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 28, https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2024.3477947 (2024).

Zbontar, J. et al. fastMRI: An Open Dataset and Benchmarks for Accelerated MRI. arXiv:1811.08839 https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1811.08839 (2018).

Bien, N. A.-O. et al. Deep-learning-assisted diagnosis for knee magnetic resonance imaging: Development and retrospective validation of MRNet. PLoS Med 27, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002699 (2018).

Štajduhar, I., Mamula, M., Miletić, D. & Ünal, G. Semi-automated detection of anterior cruciate ligament injury from MRI. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 140, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2016.12.006 (2017).

Alvarez Villela, M. et al. Feasibility of high-intensity interval training in patients with left ventricular assist devices: a pilot study. ESC Heart Fail 8, 498–507, https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.13106 (2021).

Yen, M. & Lo, L. H. Examining test-retest reliability: an intra-class correlation approach. Nurs Res 51, https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200201000-00009 (2002).

He, X. et al. Test Retest Reproducibility of Organ Volume Measurements in ADPKD Using 3D Multimodality Deep Learning. Acad Radiol 31, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2023.09.009 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. The Association Between Tumor Radiomic Analysis and Peritumor Habitat-Derived Radiomic Analysis on Gadoxetate Disodium-Enhanced MRI With Microvascular Invasion in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Magn Reson Imaging https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.29523 (2024).

Pilutti, D., Strumia, M. & Hadjidemetriou, S. Bi-modal Non-rigid Registration of Brain MRI Data with Deconvolution of Joint Statistics. IEEE Trans Image Process 23, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2014.2336546 (2014)

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. arXiv:2006.11239 https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2006.11239 (2020).

Zhao, K. et al. MRI Super-Resolution with Partial Diffusion Models. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 17, https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2024.3483109 (2024).

Lee, B. L. A. S. S. A. H. K. A. S. N. A. K. M. Enhanced Deep Residual Networks for Single Image Super-Solution. arXiv:1707.02921 https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1707.02921 (2017).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 9351, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1505.04597 (2015).

Chen, X., Fan, X., Meng, Y. & Zheng, Y. AI-driven generalized polynomial transformation models for unsupervised fundus image registration. Front Med (Lausanne) 16, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1421439 (2024).

Haubold, J. A.-O. et al. Contrast agent dose reduction in computed tomography with deep learning using a conditional generative adversarial network. Eur Radiol 31, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-021-07714-2 (2021).

Robeson, S. A.-O. & Willmott, C. J. Decomposition of the mean absolute error (MAE) into systematic and unsystematic components. PLoS One 17, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279774 (2023).

Wang, Y. & Shi, F. KMAR-50K-part1. Mendeley Data https://doi.org/10.17632/xw7mrg7ntg.5 (2025).

Wang, Y. & Shi, F. KMAR-50K-part2. Mendeley Data https://doi.org/10.17632/95w9f5tzz8.6.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Talent Program of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (No.30420220145).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. worked on the concept of the dataset. Y.X. and R.L. worked on the image inclusion. Y.X. and Y.L. performed the quality control and subjective evaluation of the data. F.W. Q.Z. and F.S. wrote the simulation scripts and performed the model-based technical validation. Y.X. and F.W. wrote the main parts of the manuscript; Y.W. and F.S. revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

F.W. and F.S. are employees of United Imaging Intelligence. The company has no role in designing and performing the surveillances and analyzing and interpreting the data. All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xi, Y., Wang, F., Shi, F. et al. A Multi-view Open-access Dataset of Paired Knee MRI for Motion Artifact Removal. Sci Data 12, 1173 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05439-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05439-1