Abstract

Modulation of behavioural responses by neuronal signalling pathways remains incompletely understood. Signalling via mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascades regulates multiple neuronal functions. Here, we show that neuronal p38α, a MAP kinase of the p38 kinase family, has a critical and specific role in modulating anxiety-related behaviour in mice. Neuron-specific p38α-knockout mice show increased levels of anxiety in behaviour tests, yet no other behavioural, cognitive or motor deficits. Using CRISPR-mediated deletion of p38α in cells, we show that p38α inhibits c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activity, a function that is specific to p38α over other p38 kinases. Consistently, brains of neuron-specific p38α-knockout mice show increased JNK activity. Inhibiting JNK using a specific blood-brain barrier-permeable inhibitor reduces JNK activity in brains of p38α-knockout mice to physiological levels and reverts anxiety behaviour. Thus, our results suggest that neuronal p38α negatively regulates JNK activity that is required for specific modulation of anxiety-related behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases are centrally involved in signal transduction of mammalian cells. The MAP kinase families c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) and p38 MAP kinases – together also termed stress-activated protein kinases (SAPKs) – were mostly studied in the context of cellular stressors such as inflammatory cytokines and other danger signal molecules, UV radiation or osmotic stress1. In fact, p38 was discovered as a kinase responsive to inflammatory stimuli2. Four individual genes termed p38α (MAPK14), p38β (MAPK11), p38γ (MAPK12) and p38δ (MAPK13) encode p38 isoforms in mammalian organisms3. Despite significant similarity (~60% primary sequence identity), non-redundant functions in different cell types have been discovered for the individual p38 genes, which suggest physiological functions of p38 kinases beyond stressor-related signalling4,5,6,7.

While substantial work has been done on p38 isoforms in non-neuronal cells (reviewed in7,8,9), non-redundant functions of p38 isoform in neurons and cognitive processes are incompletely understood. Due to the specificity of compound inhibitors towards p38α, studies have focussed on functions of this p38 kinase and have suggested roles for neuronal p38α in neurodegeneration10,11,12,13. Results from p38α gene-targeted mice imply a specific contribution of p38α in dorsal Raphe nucleus neurons to opioid-induced addictive behaviour14,15. Thus, insights on behavioural regulation by neuronal p38α have mainly been obtained from gene targeting in specific subsets of neurons. We recently showed that pan-neuronal p38α is dispensable for modulating progression of excitotoxic seizures induced by the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) antagonist pentylenetetrazole5. p38α may yet be involved in other modes of neurotoxicity12,16. However, effects of a pan-neuronal p38α deletion on behaviour are not known.

Genetic deletion of p38α has been reported for different cell types, such as in hepatocytes, keratinocytes or in cells of the immune system17,18. Deletion of p38α in early hematopoietic progenitor cells as well as in fibroblasts results in cell-autonomous hyperproliferation19. Interestingly, these models show increased JNK activity in the absence of p38α, suggesting that JNK activity is regulated by p38α9. Hepatocyte-specific p38α deletion sensitizes liver to cytokine signalling due to enhanced activity of the JNK pathway17. Furthermore, hepatocytes deficient in p38α show enhanced capacity for proliferation that is dependent on increased activity of the JNK pathway19. JNK inhibition can reduce levels of cellular proliferation in myoblasts after deletion of p38α suggesting that this cross-talk is of functional relevance20. However, whether cross-regulation of JNK MAPK signalling by p38α is present in neurons and whether it has implications for behavioural or cognitive functions in mammalian organisms is unknown.

Here, we show that pan-neuronal deletion of p38α in mice results in increased anxiety. We show that inhibition of the JNK pathway by p38α translates also to the brain. CRISPR-mediated targeting of p38α results in low levels of p38α expression and concomitantly uncontrolled activation of JNK. Furthermore, treatment with a central nervous system (CNS)-penetrant JNK- specific inhibitor reverts abnormally high levels of active JNK and anxiety levels in p38α knockout mice. Thus, our data suggest anxiety-related behaviour in mice is modulated through inhibition of JNK by neuronal p38α.

Results and Discussion

Neuronal p38α knockout results in altered anxiety-related response

Previous studies have reported the effects of conditional deletion of p38α in the CNS, specifically targeting dopaminergic15 or serotonergic neurons21. To address outcomes of pan-neuronal deficiency of p38α, we crossed p38α floxed (p38αlox) mice22 with mice that express cre recombinase under control of the pan-neuronal murine Thy1.2 promoter23. Efficient neuron-restricted deletion in the resulting p38αΔNeu mice was confirmed by immunostaining of p38α and neuronal marker NeuN or astrocytic marker GFAP on hippocampal sections (Fig. S1A,B) and by immunoblot of cortical and hippocampal extracts (Fig. S1C). These results showed in addition that hippocampal levels of p38α protein are relatively higher as compared with cortical or cerebellar p38α levels (Fig. S1C). p38α expression was previously reported in CNS cell types other than neurons14,24. Consistently, immunoblots showed residual p38α signal in p38αΔNeu brain lysates (Fig. S1C). However, immunostaining did not show detectable p38α in p38αΔNeu mice likely due to sensitivity limitations. Pan-neuronal p38α knockout mice reproduced at Mendelian ratio, were phenotypically normal and showed normal body weight gain as well as metabolism (Fig. S1D,E).

To address functional consequences of neuronal deletion of p38α on behavioural and cognitive performance, we subjected 6-month old p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox control mice to a series of behaviour tests. To test anxiety-related behaviour based on the natural aversion of mice for open and elevated areas, we subjected mice to the elevated plus maze (EPM) paradigm25. Strikingly, p38αΔNeu mice showed significantly lower occupancy of the open arms and higher occupancy of the closed arms than p38αlox/lox controls during EPM testing (Fig. 1A–C), suggesting increased anxiety. Accordingly, the overall ratio of time spent in open to time spent in closed arms was approximately 3-fold lower in p38αΔNeu mice (Fig. 1D). Number of entries into arms and average speed were similar between both groups of mice, while there was a trend toward reduced time spent in the centre for p38αΔNeu mice (Fig. S2A–D). A tendency towards lower occupancy of open arms in the EPM was found in p38αΔNeu mice at 10–14 weeks of age, suggesting this phenotype develops with age (Fig. S2E–H). Taken together, these data suggest that neuronal p38α controls levels of anxiety in mice.

Mice with neuron-specific p38α deletion show abnormal anxiety-related responses. (A–D) Anxiety-related response in mice was tested for 5 minutes using the elevated plus maze (EPM) with p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu mice. (n = 10–11) (A) Representative EPM traces. Traces reflect movement within the first minute of testing. OA, open arm; CA, closed arm. (B) Time in the open arms (C) Time in the closed arms. (D) Ratio of time in open/time in closed arms. (E–H) Activity in a novel environment was addressed using the open field paradigm (OFT) with p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu mice. (n = 10–16) (E) Representative OFT traces. (F) Average speed in OFT (G) total distance covered in OFT. (H) Thigmotaxis index in OFT (I) Object recognition memory was addressed using the novel object recognition test (NOR) with p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu mice. (n = 10–16) Ratio of time spent with novel object/time spent with familiar object is shown. (J–N) Spatio-temporal memory acquisition and retrieval was tested using the Morris water maze (MWM) with p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu mice. (n = 8–10) (J) Representative MWM traces on acquisition day 6 (K) MWM acquisition curve on days 1–6 (L) MWM quadrant occupancy during probe trial on day 7. (M) Escape latency during visual cued trial on day 8 (N) Average swim speed during probe trial on day 7. (O) Motor assessment using the Rotarod with p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu mice. (n = 13–14) Average latency to fall is shown. Values are mean ± S.E.M. (Student’s t-test) ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05 ns, non-significant.

The open field paradigm tests locomotion, explorative and anxiety-related behaviour in a novel environment5. 6-month-old p38αΔNeu mice showed significantly lower levels of movement and total distances covered in the open field test as compared to p38αlox/lox controls (Fig. 1E–G). Though it did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.05), p38αΔNeu mice showed a trend towards more thigmotaxis, i.e. movement restricted to the periphery of the open field arena (Fig. 1H). Younger mice (10–14 weeks of age) did not show significant differences in the open field paradigm (Fig. S2I,J). Both, reduced movement and increased tendency towards thigmotaxis indicate enhanced anxiety in mice in this test paradigm26. Thus, the open field testing suggests altered anxiety-related responses in mice lacking neuronal p38α at 6 months, in line with our findings from EPM testing at this age.

Next, we addressed memory function; We used the novel object recognition (NOR) paradigm to address recognition memory27. We found no significant differences between p38αΔNeu mice and p38αlox/lox controls subjected to NOR testing, suggesting that depletion of neuronal p38α does not affect recognition memory (Figs 1I and S2E). To assess spatial learning and memory, we used the Morris Water Maze task (MWM)5. Both p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox controls showed similar learning during the acquisition phase as indicated by escape path lengths on day 6 (Fig. 1J) and progressive reduction in escape latencies (Fig. 1K). Performance during the probe trials was similar in both p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox mice, indicating that spatial memory was unaffected by lack of neuronal p38α (Fig. 1L). Escape latency and swim speed during the visual cued test phase were similar in both p38αΔNeu mice and p38αlox/lox controls (Fig. 1M,N), suggesting comparable visual and motor performance under MWM test conditions. Overall, our results from NOR and MWM testing suggest normal learning and memory in p38αΔNeu mice.

Lastly, we addressed motor performance in p38αΔNeu mice and p38αlox/lox controls using the accelerated rotating rod test (Rotarod)5 (Fig. 1O), the pole test5,28 (Fig. S2F), and by measuring grip strength5 (Fig. S2G). Performance of p38αΔNeu mice and p38αlox/lox controls was indistinguishable in all motor tests, suggesting that neuronal p38α depletion does not alter motor coordination or muscle function. In summary, using a battery of behaviour, cognitive and motor tests we revealed a specific involvement of neuronal p38α in anxiety-related behaviour.

Active p38α impairs activation of JNK in cultured cells

Previous reports have shown increased activation of JNK in different cell types lacking p38α17,18,19,29, suggesting a regulation of JNK activity by p38α. This increased JNK activity has been shown to have diverse functional consequences in these cell types17,19,30. To extend these studies, we addressed whether p38α could affect JNK activity in a heterologous cell model. Therefore, we transiently transfected 293 T human embryonic kidney cells with constitutively active p38α (p38αCA) or GFP as a control. Using anisomycin, a potent stimulator of JNK activity, we addressed JNK activation in these cells using immunoblotting of cell lysates for phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK), a marker for activation of this kinase31. Anisomycin treatment (25 μg/ml, 30 minutes) induced JNK activation much less in p38αCA-expressing cells as compared to GFP-expressing controls (Fig. 2A,B). Activation of endogenous p38 was induced to a similar extent by anisomycin treatment in both experimental and control conditions (Fig. 2A).

p38α impairs activation of JNK. (A) Expression of active p38α inhibits stimulated JNK activation in cultured cells. 293 T cells were transfected with constructs expressing either enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) as control or constitutively active p38α (p38αCA). After stimulation with anisomycin (ANI; 25 ng/ml for 30 minutes) or vehicle (VEH), cell lysates were prepared for immunoblots for pThr183/pTyr185 JNK (pJNK), JNK (Cell Signaling Technologies), pThr180/Tyr182 p38 (p-p38) and p38α. GAPDH, loading control. (B) Quantification of immunoblots from three independent experiments (Student’s t-test) ***p < 0.001 (C) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated ablation of p38α increases stimulated JNK activation. eGFP-sorted 293 T cells transfected with Cas9 and p38α gRNA-expressing constructs (CRISPR p38α) or Cas9-expressing empty vector (Cas9 EV). Two different p38α gRNAs were co-transfected. After stimulation with anisomycin (ANI; 25 ng/ml for 30 minutes) or vehicle (VEH), cell lysates were prepared for immunoblots for pThr183/pTyr185 JNK (pJNK), JNK (Sigma) and p38α. GAPDH, loading control. (D) Quantification of immunoblots from three independent experiments (Student’s t-test) ***p < 0.001 (F) Of the four p38 MAPKs, only p38α inhibits JNK activation. 293 T cells were transfected with constructs expressing constitutively active hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged p38α (p38αCA), HA-tagged p38β (p38βCA), HA-tagged p38γ (p38γCA) or p38δ (p38αCA). Cells expressing eGFP served as control. After stimulation with anisomycin (ANI; 25 ng/ml for 30 minutes) or vehicle (VEH), cell lysates were prepared for immunoblots for pThr183/pTyr185 JNK (pJNK), JNK, pThr180/Tyr182 p38 (p-p38), HA and p38δ. GAPDH, loading control. Representative blots from two experiments are shown.

We next addressed JNK activation when p38α expression was abolished. To achieve targeted disruption of the MAPK14 gene in human 293 T cells, we employed CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing32. Excision of exon 1 in the murine Mapk14 gene is sufficient to ablate gene product22. The murine and human p38α loci have similar exon structure, and exon 1 contains the start codon in both species (Fig. S3A). Therefore, we targeted exon 1 in the human MAPK14 by CRISPR. A combination of two guide RNAs targeting the MAPK14 gene was efficient in abolishing detectable levels of p38α (Figs 2C,D and S3B). This resulted in increased activation of JNK upon stimulation with anisomycin as compared with Cas9-expressing control cells (Fig. 2C,D). Thus, modulation of p38α inversely correlates with stimulus-dependent JNK activation in cultured cells.

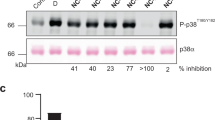

We next addressed specificity among p38 MAP kinase family members for this effect on JNK activation. Expression of active p38β, p38γ or p38δ did not result in lower JNK activation levels after stimulation with anisomycin (Fig. 2E). Thus, an inhibitory effect of active p38 kinase on JNK activity appears specific to the p38α family member of p38 kinases. Taken together, our data confirm p38α-mediated inhibition of JNK activation as a cell-autonomous mechanism prevalent in different mammalian cell types and further suggest that this function is unique to p38α compared with the other p38 kinases.

Neuronal p38α deletion results in increased JNK activation

We next addressed whether neuronal deletion of p38α would result in higher JNK activity in the CNS. Addressing JNK activation first by immunoblotting, we found higher levels of pJNK in hippocampal lysates of p38αΔNeu mice as compared to p38αlox/lox controls at 6 months of age and under physiological conditions (Fig. 3A,B). Furthermore, we did not find differences in levels of activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) between p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox control mice (Fig. 3A,B), suggesting that deficiency of p38α does not affect the ERK MAP kinase cascade. Deletion of p38α in hematopoietic lineage or in fibroblasts results in elevated proliferation and cell numbers19. To address whether neuronal deletion of p38α affects numbers of neurons, we sectioned brains from p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox control mice at 6 months of age and performed Nissl staining or immunostaining for NeuN, a marker for neuronal nuclei33. Nissl staining showed normal development and size of all brain structures. Furthermore, we addressed thickness of NeuN-positive neuronal cell layers in the hippocampal formation (Figs 3C,D and S4). Cell layers were of similar thickness in CA1, CA3 and DG cell layers in both p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox brains (Fig. 3C,D). This suggests that deletion of p38α has no significant effect on hippocampal development or on neuronal numbers in the hippocampus. GFAP immunoreactive cells, a marker of astrocytes in adult mice, were also similarly distributed in hippocampi of p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox control mice (Fig. 3C,E). Cortical neuronal layer structure was similar between p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox control mice. Increased JNK activation in neurons has been linked to cell death34. Despite higher levels of JNK activity in p38αΔNeu hippocampus, neuronal and astrocytic numbers appear normal, suggesting that elevated levels of active JNK are without adverse consequences on cell viability, development or glial reactivity in p38αΔNeu mice.

Neuron-specific p38α deletion results in increased hippocampal JNK activation in mice. (A) Immunoblots of hippocampal lysates (RIPA buffer with 10 µM okadaic acid) from p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu mice (n = 5) were probed for pThr183/pTyr185 JNK (pJNK) using 2 independent antibodies (pJNK Ab#1 and Ab#2), JNK, pThr202/pTyr204 ERK (pERK), ERK and p38α. Gapdh, loading control. Note the high levels of pJNK in p38αΔNeu as compared to p38αlox/lox. (B) Quantification of immunoblots shown in (A). p38α levels are expressed relative to Gapdh levels. pJNK and pERK levels are expressed relative to total JNK and total ERK, respectively, and normalized to Gapdh levels. (n = 5) values are mean ± S.E.M. (Student’s t-test) ***p < 0.001; ns, non-significant. (C) Hippocampal sections (5 µm) of p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu mice were prepared and immunostained for astrocytic marker GFAP and neuronal nuclear marker NeuN. Scale bar, 100 µm. Note the similar hippocampal structure, neuronal and astrocytic numbers in p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu mice. (D) Thickness of NeuN+ cell layers in the hippocampus of p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu mice. CA1, cornu ammonis 1; CA3, cornu ammonis 3; DG, dentate gyrus. (n = 5) values are mean ± S.E.M. (Student’s t-test) ns, non-significant. (E) Numbers of GFAP-positive astrocytic cells in the hippocampus of p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu mice. MOL, molecular layer; SR, stratum radiatum. (n = 5) values are mean ± S.E.M. (Student’s t-test) ns, non-significant.

JNK inhibitor reduces JNK activity in p38α-deficient mice to wild-type levels

We next addressed whether a mechanistic relationship existed between p38α-mediated inhibition of JNK activity and the anxiety-related behaviour of p38α-deficient mice. To modulate JNK activity, we compared reported properties of previously characterized pharmacological JNK inhibitors35. The D-amino acid peptide-based inhibitor D-JNKi was shown to impair JNK activity in rodents upon crossing the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) with high selectivity and a half-life that makes it suitable for acute in vivo studies of behavioural processes36,37,38,39,40. Cells treated with D-JNKi reduced JNK activation upon treatment with anisomycin (Fig. 4A), similar to SP600,125, as widely used JNK inhibitor35. This confirmed inhibition of JNK by D-JNKi.

D-JNKi reduces JNK activation in neuronal p38α knockout mice to levels in control mice. (A) 293 T cells were treated with D-JNKi (1 μM), SP600125 (10 μM) for 30 minutes at 37 °C. After stimulation with anisomycin (ANI; 25 ng/ml for 30 minutes) or vehicle (VEH), cell lysates were prepared for immunoblots for pThr183/pTyr185 JNK (pJNK), JNK. GAPDH, loading control. (B) Quantification of immunoblots in (A). (n = 3) (Student’s t-test) ***p < 0.001. (C) Immunoblots of hippocampal lysates from p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu mice 30 minutes post-application (i.p.) of D-JNKi (0.3 mg/kg body weight) or control vehicle (VEH). Immunoblots were probed for pThr183/pTyr185 JNK (pJNK), JNK, p38α and Gapdh. 30 minutes post injection of D-JNKi, activation levels of JNK were comparable between p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu brains, whereas control-treated p38αΔNeu brains show consistently higher levels of active JNK than control-treated p38αlox/lox. (n = 5) (D) Quantification of immunoblots in (A). (n = 5) (Student’s t-test) ***p < 0.001.

Next, we injected p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox controls with D-JNKi (0.3 mg/kg body weight i.p.38) or a vehicle control solution and addressed JNK activation levels in the hippocampus 30 minutes post-injection by immunoblotting. Hippocampal lysates of p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox control mice that were injected with D-JNKi showed significantly lower levels of p-JNK as compared with lysates from vehicle treated mice (Fig. 4B,C). Notably, D-JNKi-injected p38αΔNeu mice showed levels of p-JNK that were comparable to vehicle-injected p38αlox/lox control mice (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that increased JNK activation in p38αΔNeu mice is amenable to acute modulation by D-JNKi treatment.

Inhibition of JNK restores anxiety-related behaviour in p38α ΔNeu mice

We addressed functional consequences of acute reduction of JNK activation in p38αΔNeu mice on anxiety-related behaviour in the EPM paradigm. p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox control mice were treated with D-JNKi (0.3 mg/kg body weight i.p.) or vehicle 30 minutes prior to EPM testing. As expected, vehicle-injected mice lacking neuronal p38α showed significantly lower occupancy of the open maze arms than p38αlox/lox control mice after vehicle injection (Fig. 5A–C). However, both p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox control mice spent similar amounts of time in open arms after injection with D-JNKi (Fig. 5A–C). The average speed of vehicle-treated p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox control mice was comparable, as was the average speed of D-JNKi-treated p38αΔNeu and p38αlox/lox control mice (Fig. 5D). However, D-JNKi application enhanced general locomotion in mice (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that lowering JNK activity using D-JNKi can acutely revert the altered anxiety-related behaviour in p38αΔNeu mice. This supports the mechanistic concept that neuronal p38α controls behavioural states relevant to anxiety through inhibition of JNK in the CNS. Thus, the p38α-JNK pathway can support physiological functions in the CNS related to anxiety behaviour.

Inhibition of JNK restores anxiety-related behaviour in neuronal p38α knockout mice. (A–D) EPM tests (2 minutes) in p38αlox/lox and p38αΔNeu mice 30 minutes post-application (i.p.) of D-JNKi (0.3 mg/kg body weight) or control vehicle (VEH). (n = 15–16). (A) Representative EPM traces reflect movement within the first 2 minutes of testing. OA, open arm; CA, closed arm. (B) Time in the open arms. (C) Time in the closed arms. (D) Ratio of time in open/time in closed arms. Values are mean ± S.E.M. (ANOVA) **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 ns, non-significant.

Our results show that inhibition of JNK activation by neuronal p38α controls anxiety-related behaviour in mice. JNK activity is constitutively higher in mammalian brain as compared with other tissues41, suggesting that the brain maintains high JNK activity for physiological functions. JNK signalling has been previously linked to regulation of anxiety in rodents. Jnk1-deficient mice or mice after long-term treatment with D-JNKi present with reduced responses in anxiety-related behaviour42,43. Though other mouse models with specifically increased JNK activity in the CNS have not been reported, phenotypes of mice with genetic mkp-1 deletion are of note; mkp-1-deficient mice show increased activity of JNK, ERK and p38 MAP kinase in the brain, are more resilient to stress and show decreased anxiety levels in the EPM44. However, the individual contributions of the different MAP kinase families to behaviour in mkp-1 knockout mice remain unclear, leaving it uncertain whether the effects in mkp-1-deficient mice can be attributed to activity of JNK. Our results using JNK inhibitor D-JNKi in p38αΔNeu mice support the idea, however, that neuronal JNK activity specifically contributes to dysregulation of anxiety responses with increased anxiety behaviour in the EPM and open field paradigms. Though our experimental control is consistent with other studies using D-JNKi, further experiments using a scrambled D-amino acid peptide control may be needed in future studies, based on experience with similar peptide kinase inhibitors45.

During development, JNK1 is required for migration of cortical interneurons46. However, cortex and hippocampal formation of p38αΔNeu mice were histologically normal. Furthermore, the Thy1.2 promoter-driven deleter strain we employed expresses cre recombinase postnatally in forebrain neurons23. The observed anxiety-related phenotype of p38αΔNeu mice during testing is unlikely due to developmental alterations, since JNK inhibition fully reverted the deficits. In addition, p38αΔNeu mice do not show overt neurological phenotypes and develop normally.

Aberrant protein kinase-mediated signal transduction in neurons may contribute to development and persistence of anxiety-related disorders such as depression47 and other psychiatric disorders34. Understanding molecular pathways that are important in these disorders is critical to inform development of anxiolytic drugs. Studies in mouse models suggest that p38 and JNK MAP kinases are both valuable targets in anxiety disorders21,42. Beyond anxiety-related disorders, inhibition of p38α has been suggested as a treatment for neurological diseases, including neurodegeneration13,48,49,50 and neuropathic pain51. Our study suggests that inhibition of neuronal p38α may result in altered anxiety-related behaviour, which is important to bear in mind when considering p38α inhibitors as a therapeutic option.

Methods

Mice

Mice with targeted (floxed) mapk14 (p38alpha) allele on a C57BL6 background have previously been described22. Neuron-specific cre deleter strain Tg(Thy1-cre)1Vln/J on a C57BL6 background has been described before23. Mice were housed in 12 hour/12 hour light-dark cycle with food ad libitum (Rodent chow; Gordon Specialty Feeds). Genotyping was performed by PCR on DNA isolated from tail biopsies using the following oligonucleotide primers: p38αloxfwd 5′TCCTACGAGCGTCGGCAAGGTG’3, p38αloxrev 5′AGTCCCCGAGAGTTCCTGCCTC3′, Thy1.2-Cre-fwd 5′GCGGTCTGGCAGTAAAAACTATC3′, Thy1.2-Cre-rev 5′GTGAAACAGCATTGCTGTCACTT3′. Experiments were performed with age-matched mice and equal distribution of genders in experimental groups. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of the University of New South Wales. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Behaviour testing

Elevated plus maze: Anxiety-related behaviour was addressed in the elevated plus maze as previously described25. Briefly, mice were placed individually in an elevated 50 × 50 cm2 cross-shaped maze with 2 closed and 2 open arms (Stölting) in a brightly lit environment and movements were recorded. Starting position was in the centre of the maze. Mice had not been exposed to the EPM before. Maze was wiped with 70% ethanol between recordings. Movements were tracked using the AnyMaze software (Stölting).

Open field paradigm: Novelty-induced locomotion and anxiety-related behavior was assessed in the open field test paradigm as previously described52. Briefly, mice were placed individually in 40 × 40 cm2 boxes in dimly lit sound-insulated enclosures and movements were recorded for 15 minutes. Mice had not been exposed to open field paradigm before. Boxes were wiped with 70% ethanol between recordings. Tracking analysis (AnyMaze, Stölting) was either accumulated over entire recording period or split in 1-minute bins. Thigmotaxis index was calculated as ratio of time spent in the periphery of the OFT arena and the time spent in the centre of the OFT arena.

Morris water maze: Spatial learning/memory was tested in the Morris Water maze paradigm5,53. Briefly, a custom-built water tank for mouse Morris Water maze (122 cm diameter, 50 cm height) with white non-reflective interior surface in a room with low-light indirect lighting was filled with water (19–22 °C) containing diluted non-irritant white dye. Four different distal cues were placed surrounding the tank at perpendicular positions of the 4 quadrants. In the target quadrant (Q1), a platform (10 cm2) was submerged 1 cm below the water surface. Videos were recorded on CCD camera and analyzed using AnyMaze Software. For spatial acquisition, four trials of each 60 seconds were performed per session. The starting position was randomized along the outer edge of the start quadrant for all trials. To test reference memory, probe trials without platform were performed for a trial duration of 60 seconds, and recordings were analyzed for time spent within each quadrant. For visually-cued control acquisition (to exclude vision impairments), a marker was affixed on top of the platform and four trials (60 s) per session were performed. All mice were age and gender-matched and tested at 4 months of age. Mice that displayed continuous floating behavior were excluded. Genotypes were blinded to staff recording trials and analyzing video tracks. Tracking of swim paths was done using the AnyMaze software (Stolting). Average swimming speed was determined to exclude motor impairments.

Novel object recognition task: Object recognition was tested as previously described27. After a habituation phase of 15 minutes in the test arena consisting of a 40 × 40 cm2 box in a dimly lit sound-insulated enclosure, mice were faced with 2 identical objects for 10 minutes. After one hour, mice were faced with one familiar and a novel object in the same location for 5 minutes. Movements were videorecorded and analysed by tracking software (AnyMaze, Stolting). Time of interaction with objects were summed up and ratio of interaction with novel object and total object time was calculated.

Rotarod: Motor performance was tested on a 5-wheel Rota-Rod treadmill (Ugo Basile) in acceleration mode (5–60 rpm) over 120 (aged) or 180 (young) seconds5. The longest time each mouse remained on the turning wheel out of 3 attempts per session was recorded.

Grip strength: Grip strength was determined as previously described5. Briefly, the force required to pull mice off a metal wire was measured using a grip strength meter (Chatillon, AMETEK). Mice were placed such that they had a double grip on a thin metal wire attached to the meter, and they were pulled away from the meter in a horizontal direction until they let go, and a peak force (N) was recorded at the moment when the mice let go. The highest force from three attempts was recorded.

Glucose metabolism

Glucose tolerance tests were done as previously reported54. After overnight fasting, mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with D-glucose (2 mg/g) and blood was sampled from tail vein at indicated time points. Glucose was measured on handheld glucometer (Abbott).

Cell culture

293 T cells were cultured in complete growth medium consisting of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco), 10% FCS (Gibco), L-Glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin. 293 T cells were transfected by calcium precipitation or polyehtyleneimine (PEI) lipofection. Anisomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide and further diluted to final concentration in complete growth medium.

CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing of the MAPK14 locus

Design of guide RNAs (gRNAs) was performed as previously described32 using the Massachusetts Institute of Technology webtool (http://crispr.mit.edu/). gRNAs templates for MAPK14 were: gRNA#1 5′-GAGGCCCACGTTCTACCGGC-3′ gRNA#2 5′-CTGCCGCTGGAAAATGTCTC-3′. gRNA template oligos were inserted into pX458 (Addgene; 48138) by oligocloning. 293 T cells were transfected using polyethyleneimine (PEI)55. 16 hours post-transfection, cells were trypsinized, washed with PBS and resuspended in FACS sorting buffer (2%FCS, 2 mM EDTA, PBS pH 7.4). eGFP-positive cells were sorted on a FACSAria (BD). Empty pX458-transfected cells were sorted as control culture. After sorting, cells were cultured for subsequent experiments and genomic DNA was isolated by isopropanol precipitation to address genome targeting of the MAPK14 locus by PCR. Primers for MAPK14 genotyping of 293 T cells were: forward: 5′-AGCGCAAGGTCCCCGCCCGGCTG-3′ reverse: 5′-ACCCTGCCCACAGCGGCCCCAGG-3′.

p38 expression constructs

Plasmid constructs for expression of p38 isoforms were described previously5. Constitutively active variants were based on single amino acid exchange variants previously described56.

Tissue lysates

Brain tissue was homogenised in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20 mM sodium fluoride, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% nonident P40 and 0.1% protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science, Sydney, Australia)) using a dounce homogenizer (Heidolph). Okadaic acid (10 μM) was added to RIPA buffer where indicated in the figure legend. Insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation (16,000 g, 10 minutes, 4 °C). Supernatant was transferred to a new tube and protein concentration was determined by BCA assay (BioRad).

Histology and immunofluorescence

Mice were transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS pH 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Tissue was extracted and post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight. Tissue was processed in an Excelsior tissue processor (Thermo) for paraffin embedding. For frozen section, mice were transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS pH 7.4, brain tissue was extracted and post-fixed in 4% PFA overnight. Tissue was then processed at 4 °C in 10% sucrose in PBS pH7.4 for 1 hour, in 20% sucrose in PBS pH 7.4 for 1 hour, followed by 30% sucrose PBS pH 7.4 overnight. Sections (10 μm) were prepared on a cryostat (Leica). Immunofluorescence staining was done as previously described57. Briefly, tissue sections (5 μm) were rehydrated, washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS pH 7.4), permeabilised with 0.02% NP-40 in PBS and blocked with blocking buffer (3% horse serum/1% bovine albumin in PBS pH 7.4). Primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer were incubated over-night at 4 °C or for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing with PBS, secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer with or without addition of DAPI to visualize cell nuclei were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were then washed and mounted using anti-fade mounting medium (Prolong Gold, Life Technologies). Secondary antibodies used were coupled to Alexa 488, 555, 568 or 647 dyes (Molecular Probes). Epifluorescence imaging was done on a BX51 bright field/epifluorescence microscope (UPlanFL N lenses [∞/0.17/FN26.5]: 10×/0.3, 20×/0.5, 40×/0.75, 60×/1.25 oil and 100×/1.3 oil) equipped with a DP70 color camera (Olympus) using CellSens software (Olympus). Mean cell counts for GFAP+ cells in the molecular outer layer and stratum radiatum were normalized to cell density and expressed as number of GFAP+ cells per mm2 using a Java-based image processing program (ImageJ). For NeuN+ immunostaining, mean counts across layers CA1, CA3 and DG were normalized to the length and size of the respective areas and expressed as a measure of NeuN+ layer thickness.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described4. Signal was visualized by chemiluminescence on X-ray films or by digital acquisition on a ChemiDoc MP (Biorad). Densitometric quantification of Western blot results was performed using ImageJ 2.0.0-rc-49/1.51d (NIH). Antibodies used were phospho-T202/Y204 ERK (D13.14.4E; Cell Signaling Technologies), ERK (Cell Signaling Technologies), phospho-T183/Y185 JNK (81E11; Cell Signaling Technologies), phospho-T183/Y185 JNK (98F2; Cell Signaling Technologies), JNK1/2/3 (Cell Signaling Technologies), JNK (Sigma), phospho-T180/Y182 p38 (D3F9; Cell Signaling Technologies), p38α (Cell Signaling Technologies), GAPDH (Millipore), NeuN (Abcam), GFAP (Abcam).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using Graphpad Prism (v7.0c). For data comparisons of 2 experimental groups of data unpaired, two-tailed Student t-test was used. For comparisons for >2 groups of data, ANOVA was used. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. unless stated otherwise in the figure legend.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kyriakis, J. M. & Avruch, J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol Rev 81, 807–869, https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807 (2001).

Han, J., Lee, J. D., Bibbs, L. & Ulevitch, R. J. A. MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science 265, 808–811 (1994).

Raman, M., Chen, W. & Cobb, M. H. Differential regulation and properties of MAPKs. Oncogene 26, 3100–3112, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1210392 (2007).

Ittner, A. et al. Regulation of PTEN activity by p38delta-PKD1 signaling in neutrophils confers inflammatory responses in the lung. J Exp Med 209, 2229–2246, https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20120677 (2012).

Ittner, A. et al. Site-specific phosphorylation of tau inhibits amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer’s mice. Science 354, 904–908, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah6205 (2016).

Sumara, G. et al. Regulation of PKD by the MAPK p38delta in insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis. Cell 136, 235–248, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.018 (2009).

Cuenda, A. & Sanz-Ezquerro, J. J. p38gamma and p38delta: From Spectators to Key Physiological Players. Trends Biochem Sci 42, 431–442, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2017.02.008 (2017).

Takeda, K. & Ichijo, H. Neuronal p38 MAPK signalling: an emerging regulator of cell fate and function in the nervous system. Genes Cells 7, 1099–1111 (2002).

Arthur, J. S. & Ley, S. C. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 13, 679–692, https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3495 (2013).

Dau, A., Gladding, C. M., Sepers, M. D. & Raymond, L. A. Chronic blockade of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors ameliorates synaptic dysfunction and pro-death signaling in Huntington disease transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis 62, 533–542, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2013.11.013 (2014).

Ittner, A. A., Gladbach, A., Bertz, J., Suh, L. S. & Ittner, L. M. p38 MAP kinase-mediated NMDA receptor-dependent suppression of hippocampal hypersynchronicity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2, 149, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-014-0149-z (2014).

Li, S. et al. Soluble Abeta oligomers inhibit long-term potentiation through a mechanism involving excessive activation of extrasynaptic NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. J Neurosci 31, 6627–6638, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0203-11.2011 (2011).

Roy, S. M. et al. Targeting human central nervous system protein kinases: An isoform selective p38alphaMAPK inhibitor that attenuates disease progression in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. ACS Chem Neurosci 6, 666–680, https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00002 (2015).

Bruchas, M. R. et al. Selective p38alpha MAPK deletion in serotonergic neurons produces stress resilience in models of depression and addiction. Neuron 71, 498–511, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.011 (2011).

Ehrich, J. M. et al. Kappa Opioid Receptor-Induced Aversion Requires p38 MAPK Activation in VTA Dopamine Neurons. J Neurosci 35, 12917–12931, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2444-15.2015 (2015).

Cao, J. et al. Distinct requirements for p38alpha and c-Jun N-terminal kinase stress-activated protein kinases in different forms of apoptotic neuronal death. J Biol Chem 279, 35903–35913, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M402353200 (2004).

Heinrichsdorff, J., Luedde, T., Perdiguero, E., Nebreda, A. R. & Pasparakis, M. p38 alpha MAPK inhibits JNK activation and collaborates with IkappaB kinase 2 to prevent endotoxin-induced liver failure. EMBO Rep 9, 1048–1054, https://doi.org/10.1038/embor.2008.149 (2008).

Kim, C. et al. The kinase p38 alpha serves cell type-specific inflammatory functions in skin injury and coordinates pro- and anti-inflammatory gene expression. Nat Immunol 9, 1019–1027, https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.1640 (2008).

Hui, L. et al. p38alpha suppresses normal and cancer cell proliferation by antagonizing the JNK-c-Jun pathway. Nat Genet 39, 741–749, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng2033 (2007).

Perdiguero, E. et al. Genetic analysis of p38 MAP kinases in myogenesis: fundamental role of p38alpha in abrogating myoblast proliferation. EMBO J 26, 1245–1256, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7601587 (2007).

Baganz, N. L. et al. A requirement of serotonergic p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase for peripheral immune system activation of CNS serotonin uptake and serotonin-linked behaviors. Transl Psychiatry 5, e671, https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2015.168 (2015).

Engel, F. B. et al. p38 MAP kinase inhibition enables proliferation of adult mammalian cardiomyocytes. Genes Dev 19, 1175–1187, https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1306705 (2005).

Dewachter, I. et al. Neuronal deficiency of presenilin 1 inhibits amyloid plaque formation and corrects hippocampal long-term potentiation but not a cognitive defect of amyloid precursor protein [V717I] transgenic mice. J Neurosci 22, 3445–3453, doi:20026290 (2002).

Chew, L. J., Coley, W., Cheng, Y. & Gallo, V. Mechanisms of regulation of oligodendrocyte development by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Neurosci 30, 11011–11027, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2546-10.2010 (2010).

Ke, Y. D. et al. Short-term suppression of A315T mutant human TDP-43 expression improves functional deficits in a novel inducible transgenic mouse model of FTLD-TDP and ALS. Acta Neuropathol 130, 661–678, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1486-0 (2015).

Simon, P., Dupuis, R. & Costentin, J. Thigmotaxis as an index of anxiety in mice. Influence of dopaminergic transmissions. Behav Brain Res 61, 59–64 (1994).

Leger, M. et al. Object recognition test in mice. Nat Protoc 8, 2531–2537, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.155 (2013).

Carter, R. J., Morton, J. & Dunnett, S. B. Motor coordination and balance in rodents. Curr Protoc Neurosci Chapter 8, Unit 8 12, https://doi.org/10.1002/0471142301.ns0812s15 (2001).

Xiao, Y. T., Yan, W. H., Cao, Y., Yan, J. K. & Cai, W. P38 MAPK Pharmacological Inhibitor SB203580 Alleviates Total Parenteral Nutrition-Induced Loss of Intestinal Barrier Function but Promotes Hepatocyte Lipoapoptosis. Cell Physiol Biochem 41, 623–634, https://doi.org/10.1159/000457933 (2017).

Wada, T. et al. Antagonistic control of cell fates by JNK and p38-MAPK signaling. Cell Death Differ 15, 89–93, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4402222 (2008).

Fleming, Y. et al. Synergistic activation of stress-activated protein kinase 1/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK1/JNK) isoforms by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4) and MKK7. Biochem J 352(Pt 1), 145–154 (2000).

Ran, F. A. et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc 8, 2281–2308, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.143 (2013).

Wolf, H. K. et al. NeuN: a useful neuronal marker for diagnostic histopathology. J Histochem Cytochem 44, 1167–1171 (1996).

Coffey, E. T. Nuclear and cytosolic JNK signalling in neurons. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 15, 285–299, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3729 (2014).

Koch, P., Gehringer, M. & Laufer, S. A. Inhibitors of c-Jun N-terminal kinases: an update. J Med Chem 58, 72–95, https://doi.org/10.1021/jm501212r (2015).

Borsello, T. et al. A peptide inhibitor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase protects against excitotoxicity and cerebral ischemia. Nature medicine 9, 1180–1186, https://doi.org/10.1038/nm911 (2003).

Davoli, E. et al. Determination of tissue levels of a neuroprotectant drug: the cell permeable JNK inhibitor peptide. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 70, 55–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vascn.2014.04.001 (2014).

Manassero, G. et al. Role of JNK isoforms in the development of neuropathic pain following sciatic nerve transection in the mouse. Mol Pain 8, 39, https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-8-39 (2012).

Nijboer, C. H. et al. Inhibition of the JNK/AP-1 pathway reduces neuronal death and improves behavioral outcome after neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Brain Behav Immun 24, 812–821, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2009.09.008 (2010).

Repici, M. et al. Time-course of c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation after cerebral ischemia and effect of D-JNKI1 on c-Jun and caspase-3 activation. Neuroscience 150, 40–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.08.021 (2007).

Liu, Y. F., Bertram, K., Perides, G., McEwen, B. S. & Wang, D. Stress induces activation of stress-activated kinases in the mouse brain. J Neurochem 89, 1034–1043, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02391.x (2004).

Mohammad, H. et al. JNK1 controls adult hippocampal neurogenesis and imposes cell-autonomous control of anxiety behaviour from the neurogenic niche. Mol Psychiatry 23, 362–374, https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.203 (2018).

Reinecke, K., Herdegen, T., Eminel, S., Aldenhoff, J. B. & Schiffelholz, T. Knockout of c-Jun N-terminal kinases 1, 2 or 3 isoforms induces behavioural changes. Behav Brain Res 245, 88–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2013.02.013 (2013).

Duric, V. et al. A negative regulator of MAP kinase causes depressive behavior. Nature medicine 16, 1328–1332, https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2219 (2010).

Volk, L. J., Bachman, J. L., Johnson, R., Yu, Y. & Huganir, R. L. PKM-zeta is not required for hippocampal synaptic plasticity, learning and memory. Nature 493, 420–423, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11802 (2013).

Myers, A. K., Meechan, D. W., Adney, D. R. & Tucker, E. S. Cortical interneurons require Jnk1 to enter and navigate the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci 34, 7787–7801, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4695-13.2014 (2014).

Inamdar, A. et al. Evaluation of antidepressant properties of the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor losmapimod (GW856553) in Major Depressive Disorder: Results from two randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicentre studies using a Bayesian approach. J Psychopharmacol 28, 570–581, https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881114529377 (2014).

Alam, J. & Scheper, W. Targeting neuronal MAPK14/p38alpha activity to modulate autophagy in the Alzheimer disease brain. Autophagy 12, 2516–2520, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2016.1238555 (2016).

Schnoder, L. et al. Deficiency of Neuronal p38alpha MAPK Attenuates Amyloid Pathology in Alzheimer Disease Mouse and Cell Models through Facilitating Lysosomal Degradation of BACE1. J Biol Chem 291, 2067–2079, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M115.695916 (2016).

Colie, S. et al. Neuronal p38alpha mediates synaptic and cognitive dysfunction in an Alzheimer’s mouse model by controlling beta-amyloid production. Sci Rep 7, 45306, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45306 (2017).

Ji, R. R. & Suter, M. R. p38 MAPK, microglial signaling, and neuropathic pain. Mol Pain 3, 33, https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-3-33 (2007).

Przybyla, M. et al. Disinhibition-like behavior in a P301S mutant tau transgenic mouse model of frontotemporal dementia. Neurosci Lett 631, 24–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2016.08.007 (2016).

Vorhees, C. V. & Williams, M. T. Morris water maze: procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nat Protoc 1, 848–858, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2006.116 (2006).

Ittner, A. A. et al. The nucleotide exchange factor SIL1 is required for glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from mouse pancreatic beta cells in vivo. Diabetologia 57, 1410–1419, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-014-3230-z (2014).

Stefanoska, K. et al. An N-terminal motif unique to primate tau enables differential protein-protein interactions. J Biol Chem. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA118.001784 (2018).

Avitzour, M. et al. Intrinsically active variants of all human p38 isoforms. FEBS J 274, 963–975, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05644.x (2007).

Ittner, A. et al. Tau-targeting passive immunization modulates aspects of pathology in tau transgenic mice. J Neurochem 132, 135–145, https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.12821 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Troy Butler and the staff of the Biological Resource Centre at University of New South Wales for their assistance. This research has been supported by funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (1081916, 1123564, 1132524, 1136241, 1143848, 1143978), the Australian Research Council (DP150104321, DP170100781, DP170100843) to L.I. and A.I.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S., J.B., A.M.V., J.v.d.H., A.I. performed experiments. K.S., J.B., A.M.V. and A.I. analysed data. L.M.I and A.I. designed the study. K.S., J.B., L.M.I. and A.I. wrote the majority of the manuscript. All authors contributed to writing of the manuscript. A.I. supervised the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stefanoska, K., Bertz, J., Volkerling, A.M. et al. Neuronal MAP kinase p38α inhibits c-Jun N-terminal kinase to modulate anxiety-related behaviour. Sci Rep 8, 14296 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32592-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32592-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Jnk1 and downstream signalling hubs regulate anxiety-like behaviours in a zebrafish larvae phenotypic screen

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals Discrete Poststroke Dementia Neuronal and Gliovascular Signatures

Translational Stroke Research (2023)

-

Drug-responsive autism phenotypes in the 16p11.2 deletion mouse model: a central role for gene-environment interactions

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

A novel genomic region on chromosome 11 associated with fearfulness in dogs

Translational Psychiatry (2020)

-

Anxiety in rats with bile duct ligation is associated with activation of JNK3 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the hippocampus

Metabolic Brain Disease (2020)