Abstract

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is related to an increased risk of suicide. Although both diabetes and the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) pathway are closely associated with ACS and suicide, the effects of these factors on suicidal behavior in ACS patients have not been assessed. We investigated the individual and interaction effects of diabetes and BDNF-related markers, namely the serum BDNF (sBDNF) level and the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism, on suicidal ideation (SI) in ACS patients. The presence of diabetes was ascertained, and sBDNF levels and the presence of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism were measured in 969 patients within 2 weeks after an ACS episode. 711 patients were followed up at 1 year after the ACS episode. SI was assessed using the relevant items of the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale at baseline (acute SI) and the 1-year follow-up (chronic SI). Significant individual effects of low sBDNF levels were found on acute SI. The presence of both diabetes and a low sBDNF level or the BDNF Met/Met genotype was associated with acute SI, with multivariate logistic regression analyses revealing significant interaction effects. The highest frequency of chronic SI was seen in diabetic patients with an sBDNF level in the lowest tertile or with the BDNF Met/Met genotype, although the interaction terms were not statistically significant. Our study suggests that the combination of diabetes and BDNF-related markers, such as the sBDNF level and the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism, might provide a useful predictor of acute SI in ACS patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suicide is a global public health issue and is responsible for roughly 1 million deaths each year1. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS), which comprises unstable angina and myocardial infarction, is a serious life stressor that leads to a high risk of suicidal behavior2,3,4,5. Moreover, suicidal ideation (SI) after ACS is a risk factor for worse cardiac outcomes6. Given the association between ACS and suicide and the burdens of both, identifying risk factors for ACS-related suicidal behavior is important for developing effective prevention strategies for these patients.

Diabetes is a highly prevalent comorbidity among ACS patients and is associated with early mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events7,8,9. Diabetes also increases the risk of suicide10,11. However, whether diabetes is an additional risk factor for suicide in ACS patients has not been determined.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) may contribute to suicide risk after ACS given its associations with both suicide and ACS. The involvement of BDNF in atherosclerosis and plaque instability12 was supported by a clinical study that reported reduced levels of BDNF in ACS patients13. BDNF has also been connected with suicidal behavior according to its role in maintaining synaptic and structural plasticity in the central nervous system14,15. However, inconsistent results regarding the association between the serum BDNF (sBDNF) level and suicidal behavior have been reported in previous studies. Some studies have reported that a low sBDNF level is associated with a higher suicide risk16,17,18, whereas others have not found such significant association19,20. Because the BDNF expression is controlled by a genetic polymorphism entailing substitution of valine by methionine at codon 66 (Val66Met) in the pro-BDNF molecule, which is related with reduced secretion of BDNF21, clinical studies have been carried out to evaluate the association between BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and suicide risk. However, discrepant results have been reported. Some studies have stated that the BDNF Met/Met genotype is associated with higher suicide risk22,23,24, whereas others have not found such significant association25,26.

Because diabetes and the BDNF pathway are closely related to ACS and suicide, respectively, and the level and function of BDNF are disrupted in diabetes27,28, suicidal behavior in ACS patients may be affected by a potentially complex relationship between diabetes and the BDNF pathway. However, this has not been studied to date. On the spectrum of suicidal behaviors, which range from SI and suicide attempts to completion29, SI has been used as a phenotype of suicidal behavior in ACS patients in previous studies30,31.

The goal of this study was to investigate the interaction effects of diabetes and BDNF-related markers, i.e., the sBDNF level and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism, on acute (within 2 weeks after an ACS episode) and chronic (1 year after an ACS episode) SI in a prospective cohort of Korean patients with ACS.

Results

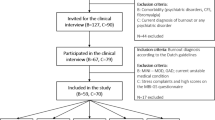

Recruitment and treatment

Patient recruitment over the 1-year period is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. Among the 1152 patients evaluated at baseline, 969 (84.1%) consented to offer blood samples. The baseline covariates did not differ significantly between those who agreed to offer blood samples and those who refused. Re-evaluation at 1 year after the ACS episode was performed in 711 (73.4%) of the 969 patients. Reasons for drop-out were loss to follow-up (N = 159), death (N = 9), refusal to participate (N = 32), and too unwell to participate (N = 13). Drop-out at the 1-year re-evaluation was significantly associated with older age and higher Killip class but not with diabetes, the sBDNF level, or presence of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism.

Baseline characteristics of presence of diabetes, sBDNF tertiles, presence of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism, and acute SI

In the baseline sample (N = 969), diabetes was present in 191 (19.7%) participants. The median (interquartile range) and mean (standard deviation) sBDNF levels were 17.8 (7.0) and 17.6 (9.4) ng/mL, respectively. The sBDNF levels were divided into tertiles: high (20.50–52.61 ng/mL), middle (14.79–20.48 ng/mL), and low (1.37–14.79 ng/mL). Val/Val, Val/Met, and Met/Met genotypes were observed in 242 (25.0%), 498 (51.4%), and 229 participants (23.6%), respectively. Acute SI was present in 195 (20.1%) participants. These variables were compared according to diabetes presence in Table 1. Presence of diabetes was significantly associated with older age, female sex, lower education level, current unemployment, higher fasting glucose level, lower total cholesterol level, higher blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level, higher score on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), hypertension, lower rate of hypercholesterolemia, lower rate of current smoking, and lower left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). The characteristics were compared according to the sBDNF tertile and presence of the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The sBDNF tertile was significantly associated with BDNF Val66Met polymorphism, age, current unemployment, hypertension, current smoking, and LVEF. Presence of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism was significantly associated with the sBDNF level, age, current unemployment, and BDI score. The characteristics were then compared according to presence of acute SI in Supplementary Table 3. The presence of acute SI was significantly associated with female sex, lower education level, rented housing, current unemployment, previous depression, and a higher score on the BDI. Eleven variables (age, sex, education, housing, currently unemployed, previous depression, BDI score, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, current smoker, and LVEF) were selected for evaluation in the subsequent adjusted analyses.

Effects of diabetes, sBDNF tertile, and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on SI

The individual effects of diabetes, sBDNF tertile, and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on SI are shown in Table 2. Diabetes was not significantly associated with SI. Compared with the high sBDNF tertile, the low tertile was significantly associated with acute SI in the adjusted analyses. Compared with the Val/Val genotype, the Val/Met and Met/Met genotypes were significantly associated with acute SI in the unadjusted analyses, but these associations were not significant after adjustment. In the 1-year follow-up evaluation (N = 711), presence of diabetes, sBDNF tertile, and presence of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism were not significantly associated with chronic SI in the unadjusted or adjusted analyses.

The interaction effects of diabetes and sBDNF tertile on acute and chronic SI are shown in Fig. 1. Diabetes was significantly associated with both acute and chronic SI only among those in the low sBDNF tertile, and significant interactions with acute SI but not with chronic SI were found after adjustment for relevant covariates. The association between diabetes and acute SI in patients with the low sBDNF tertile was dependent on fasting glucose levels (Supplementary Fig. 2). The interaction effects of diabetes and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on acute and chronic SI are shown in Fig. 2. Diabetes was significantly associated with both acute and chronic SI only in the presence of the BDNF Met/Met genotype, and a significant interaction with acute SI but not with chronic SI was found after adjustment for the relevant covariates. The association between diabetes and SI in patients with the BDNF Met/Met genotype was dependent on fasting glucose levels (Supplementary Fig. 3). The interaction effects of the sBDNF level and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on acute and chronic SI are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. No significant effects were found.

Interaction effects of diabetes and the sBDNF tertile on acute and chronic suicidal ideation in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Data are odds ratios (95% confidence interval) adjusted for age, sex, education, housing, current unemployment, previous depression, BDI score, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, current smoking, and LVEF evaluated at baseline. *P < 0.05.

Interaction effects of diabetes and the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on acute and chronic suicidal ideation in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Data are odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) adjusted for age, sex, education, housing, current unemployment, previous depression, BDI score, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, current smoking, and LVEF evaluated at baseline. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

In this study, using data from a prospective study of Korean patients with ACS, we identified significant interaction effects of diabetes with both the sBDNF level and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on acute SI, in that the incidence of acute SI was significantly higher in the presence of diabetes and a low sBDNF level or the BDNF Met/Met genotype compared with higher BDNF levels and other genotypes. These results were robust even after adjusting for the relevant covariates. Although the frequency of chronic SI was higher among diabetic patients with an sBDNF level in the lowest tertile or with the BDNF Met/Met genotype, the interactions were not statistically significant. With respect to individual effects, a significant association was found only between a lower sBDNF level and the presence of acute SI.

Diabetes reportedly increases the risk of suicide10,11, presumably due to diabetes-related complications and the high prevalence of mental disorders such as depression and anxiety32,33,34. These associations depend on the type of diabetes. Juvenile type 1 diabetes is closely related to all suicidal behaviors35,36,37, whereas in adult diabetics, the majority of whom have type 2 diabetes, inconsistent results have been reported regarding an increased risk of suicidal behavior. One study reported that diabetes was a risk factor for suicide completion38, whereas others reported no relationship39,40,41. The average and median age of diabetic patients included in this study were 62.4 years (standard deviation 9.6 years) and 64.0 years (interquartile range 14.0 years), respectively, and it is considered that most of them has type 2 diabetes. Our finding that diabetes exhibited no independent effect on acute or chronic SI was consistent with the results of many previous studies.

Because BDNF is involved in synaptic and structural plasticity in the brain14,15, abnormal BDNF function has been suggested as a biological pathway for suicide. Based on this suggestion, many clinical studies have evaluated the association between the BDNF pathway, including the sBDNF level and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism, and suicidal behavior, but the results have been inconsistent. Regarding the sBDNF level, some studies have reported an association between low sBDNF levels and a higher suicide risk16,17,18, whereas others have reported no such association19,20. Regarding the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism, some studies have found an association between the BDNF Met/Met genotype and a higher suicide risk22,23,24, whereas others have not25,26. The discrepant findings among previous studies may be the result of differences in the assessment methods for suicidal behavior and the presence and type of underlying mental disorders in the study subjects. However, discrepant results were also found between two studies with similar study designs that evaluated the association between BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and suicide attempts in depressed patients24,25. In the present study, high versus low tertiles of sBDNF levels showed an independent effect on acute SI, but the BDNF genotype did not, thus revealing discrepant results between the two BDNF-related markers. Considering our and others’ results comprehensively, BDNF-related markers alone seem to have limited value in predicting suicide risk.

In the present study, we identified an interaction effect of diabetes and a low sBDNF level or the BDNF Met/Met genotype on acute SI in ACS patients. In addition, although there were no significant interaction effects, the frequency of chronic SI was higher in diabetic patients with an sBDNF level in the lowest tertile or with the BDNF Met/Met genotype. A synergistic effect between diabetes and a low sBDNF level or the BDNF Met/Met genotype in our cohort is biologically plausible. A low peripheral BDNF level is associated with diabetes-related complications42,43. Because diabetes-related complications are related to a higher risk of SI32, diabetes may be predictive of SI only in subjects with low sBDNF levels or with the BDNF Met/Met genotype due to the high burden of those complications. In addition, because psychiatric diseases such as depression and anxiety are associated with increased suicidality in diabetics32,33,34, and a low sBDNF level and the BDNF Met/Met genotype are closely related to these psychiatric diseases44, diabetes may be a risk factor for SI only among subjects with a low sBDNF level or with the BDNF Met/Met genotype because of their high vulnerability to psychiatric diseases. Because ACS raises the risk of suicide2,3,4,5 and SI after ACS is linked to a worse illness outcome6, it’s critical to identify a high-risk group of ACS patients for suicide. However, there have been no research on biomarkers that can predict suicidal behavior in ACS patients to date. Our findings imply that assessing diabetes and BDNF-related markers in ACS patients could be used to screen high-risk groups for suicide.

It is noteworthy that interaction effects between diabetes and a low sBDNF level or the BDNF Met/Met genotype on SI were significant during the first 2 weeks but not at 1 year after an ACS episode. These results suggest that SI in ACS patients has several possible etiologies, which may vary depending on the time elapsed since the ACS diagnosis. Recently diagnosed ACS is associated with severe emotional and physical distress45,46, and the interaction effects of diabetes and altered BDNF-related markers may amplify these precipitating causes of acute SI. However, in the chronic phase, these interaction effects may disappear due to the greater influence of other factors on SI.

Several limitations to this study should be kept in mind in the interpretation of our results. First, SI, rather than suicide attempts or suicide completion, was evaluated as the primary outcome. Although SI is closely related to more severe suicidal behavior47, it is hard to generalize our findings to overall suicidal behavior in patients with ACS. However, since more severe types of suicidal behavior are rarely observed in this type of study, previous studies have also considered SI as a phenotype of suicidal behavior in ACS patients30,31. Second, SI was investigated using the “suicidal thoughts” item from the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), rather than using a formal instrument. However, the predictive validity of the suicide-related item for suicide attempts and suicide death has been demonstrated48, and the method used in this study has been applied before49. Third, diabetes assessment was based on self-report, which may have underestimated the actual prevalence of diabetes at baseline. Fourth, diabetes type and the burden of diabetes-related complications were not evaluated. However, most adults with diabetes in Korea are expected to have type 2 diabetes. Fifth, the follow-up rate for 1-year re-evaluation was relatively low compared with the baseline evaluation. Due to the poor prognostic characteristics of the ACS patients who were lost to follow-up, such as older age and a higher Killip class, this might have influenced the results. However, this likelihood is low because the baseline distributions of diabetes, sBDNF tertile, and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism did not differ by the 1-year re-evaluation follow-up status. Finally, recruitment was carried out at a single site, which may limit the study’s generalizability; however, this is also a strength as it guarantees consistency in patient evaluation and treatment.

This study has several strengths. It is the first prospective study to evaluate the interaction effects of diabetes and the BDNF pathway on SI. The BDNF pathway was evaluated using two markers, the sBDNF level and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism, which reinforced the validity of our results. All psychiatric and cardiovascular evaluations were carried out using well-validated scales. Moreover, acute SI and other covariates were assessed at similar time points (within 2 weeks of the ACS episode) in a large number of ACS patients, which reduced the risk of errors due to different examination times. The final strength was the successive recruitment of participants from all eligible ACS patients seen at the study hospital. This reduced the likelihood of selection bias and increased the generalizability of the outcomes in terms of screening patients at high risk of suicide.

Baseline diabetes and the high vs. low sBDNF level or BDNF Val/Val vs. Met/Met genotype showed multiplicative interactions in their associations with acute SI among patients with ACS. In addition, although the interaction effects were not significant, diabetes was associated with a higher frequency of chronic SI only in patients with a low sBDNF level or with the BDNF Met/Met genotype. These results suggest that the combination of diabetes and BDNF-related markers may increase the predictability of acute SI compared with each marker alone. Considering the preventive aspects, careful attention is needed for ACS patients who have both diabetes and altered BDNF-related markers; however, further studies are needed to evaluate whether additional suicide prevention practices may be beneficial in this subpopulation.

Materials and methods

Study overview and participants

All analyses were conducted using data from the Korean DEPression in ACS (K-DEPACS) study, which also included a nested randomized controlled trial, Escitalopram for DEPression in ACS (EsDEPACS) study (registration date: 08/01/2007, ClinicalTrial.gov registry number: NCT00419471). Design and results of the K-DEPACS study have been published50,51,52,53. The overview and participant recruitment algorithm for the present analysis are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Hospitalized ACS patients who satisfied the eligibility criteria (Supplementary Methods) at the Department of Cardiology of Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju, South Korea from 2006 to 2012 were consecutively recruited. The study cardiologists treated patients based on international guidelines for ACS management54. Patients who satisfied the inclusion criteria and consented to participate in the study were evaluated for baseline examinations as inpatients within 2 weeks (mean 6.3 standard deviation 2.4 days) after the ACS episode. Within this group, those who agreed to blood collections composed the baseline sample. They were followed up at 1-year after ACS for longitudinal evaluation. This study was approved by the Chonnam National University Hospital Institutional Review Board (CNUH I-2008-02-027). All participants reviewed the consent form and written informed consent was obtained.

Exposure variables

Assessment of diabetes

Information with regard to history of diabetes was obtained at the baseline evaluation. Presence of diabetes was determined as a diagnosis of diabetes by a doctor or currently administering oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin treatment. Two abnormal test results from the same sample or two distinct test samples are required for diabetes diagnosis by fasting glucose level55. Since fasting glucose levels were measured once in an acute disease condition, which could induce hyperglycemia56, fasting glucose levels were inappropriate to use as a marker of diabetes diagnosis.

Serum BDNF level

Participants were instructed to fast (except water) overnight before blood sampling. They were then requested to sit quietly and relax for 25–45 min prior to obtaining the blood samples. The sBDNF level was quantified using the Quantikine® ELISA Human BDNF Immunoassay (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) at the Global Clinical Central Lab (Yongin, Korea). The sBDNF level was classified into tertiles (high, middle, or low). Additionally, the patients were divided according to the median sBDNF level into higher and lower groups.

BDNF genotyping

The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism was determined as follows: DNA was extracted from venous blood using established protocols. The genotype was classified as Val/Val, Val/Met, or Met/Met. A detailed polymerase chain reaction protocol is presented in Supplementary Methods.

Baseline covariates

Covariates associated with suicidal behavior in ACS patients in previous study57 were evaluated within 2 weeks after the ACS episode. An evaluation was conducted to collect information on age, sex, years of education, living status (living alone or not), type of residence (owned or rented), and current occupation (employed or not). Fasting glucose, total cholesterol, BUN, and creatinine levels were measured using the Hitachi Automatic Analyzer 7600 (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). To evaluate patients’ depression characteristics, personal and family histories of depression and BDI58 were ascertained. To evaluate patients’ cardiometabolic risk factors, the following characteristics were identified: personal and family histories of ACS, diagnosed hypertension, hypercholesterolemia according to fasting serum total cholesterol level (> 200 mg/dL) or a history of hyperlipidemia with ongoing treatment, obesity based on measured body mass index (BMI, > 25 kg/m2), and reported current smoking status. To evaluate current cardiac status, Killip classification59 was investigated and LVEF was estimated by echocardiography. Cardiac enzymes, including troponin I and creatine kinase (CK)-MB, were also measured.

Outcome measure: suicidal ideation

SI was evaluated within 2 weeks after ACS (acute SI) and at 1-year after ACS (chronic SI) using the items of the MADRS for suicidal thoughts60. Participants were requested to rate whether they thought life was worth living or whether they had a suicide plan; scores ranged from 0 (life satisfaction) to 6 (explicit plans for suicide). Considering the previous study, the presence of SI was determined by a score of 2 (fleeting suicidal thoughts) or more49.

Statistical analysis

The baseline data of diabetes presence, sBDNF tertiles, presence of the BDNF val66met polymorphism, and presence of acute SI were compared using independent t-tests or chi-square tests. Covariates were selected based on the variables representing statistical significance (P < 0.05) in the baseline characteristics analyses and potential collinearity between variables. The individual effects of diabetes (absent vs. present), the sBDNF level (high vs. middle or low), and the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism (Val/Val vs. Val/Met or Met/Met) on acute and chronic SI were analyzed using logistic regression before and after adjusting for covariates. The interaction effects between diabetes and the sBDNF level or BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and between the sBDNF level and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on acute and chronic SI were analyzed by multinominal logistic regression after adjusting for potential covariates. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered to demonstrate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25).

Statement of ethics

All patients gave written informed consent to participate in the study and use their data. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 and approved by the Ethics Commission of the Chonnam National University Hospital Institutional Review Board (CNUH I-2008-02-027) as it uses de-identified data. EsDEPACS study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration date: 08/01/2007, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00419471).

References

Naghavi, M., Global Burden of Disease Self-Harm, C. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ 364(l94), 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l94 (1990).

Artero, S., Astruc, B., Courtet, P. & Ritchie, K. Life-time history of suicide attempts and coronary artery disease in a community-dwelling elderly population. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 21, 108–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1429 (2006).

Placido, A. & Sposito, A. C. Association between suicide and cardiovascular disease: Time series of 27 years. Int. J. Cardiol. 135, 261–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.034 (2009).

Larsen, K. K., Agerbo, E., Christensen, B., Sondergaard, J. & Vestergaard, M. Myocardial infarction and risk of suicide: A population-based case-control study. Circulation 122, 2388–2393. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.956136 (2010).

Liu, C. H. et al. Acute coronary syndrome and suicide: A case-referent study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5, e003998. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.003998 (2016).

Kim, J. M. et al. Impact of suicidal ideation on long-term cardiac outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome: Sex-specific differences. Psychother. Psychosom. 87, 311–312. https://doi.org/10.1159/000489788 (2018).

Donahoe, S. M. et al. Diabetes and mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 298, 765–775. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.7.765 (2007).

Lettino, M. et al. Diabetic patients with acute coronary syndromes in contemporary European registries: Characteristics and outcomes. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 3, 198–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvw049 (2017).

Zhou, M. et al. Prevalence and in-hospital outcomes of diabetes among patients with acute coronary syndrome in China: Findings from the Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China-Acute Coronary Syndrome Project. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 17, 147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0793-x (2018).

Sarkar, S. & Balhara, Y. P. Diabetes mellitus and suicide. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 18, 468–474. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.137487 (2014).

Wang, B., An, X., Shi, X. & Zhang, J. A. Management of endocrine disease: Suicide risk in patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 177, R169–R181. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-16-0952 (2017).

Ejiri, J. et al. Possible role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the pathogenesis of coronary artery disease. Circulation 112, 2114–2120. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.476903 (2005).

Manni, L., Nikolova, V., Vyagova, D., Chaldakov, G. N. & Aloe, L. Reduced plasma levels of NGF and BDNF in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Int. J. Cardiol. 102, 169–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.10.041 (2005).

Huang, E. J. & Reichardt, L. F. Neurotrophins: Roles in neuronal development and function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 677–736. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.677 (2001).

Dwivedi, Y. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and suicide pathogenesis. Ann. Med. 42, 87–96. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890903485730 (2010).

Deveci, A., Aydemir, O., Taskin, O., Taneli, F. & Esen-Danaci, A. Serum BDNF levels in suicide attempters related to psychosocial stressors: A comparative study with depression. Neuropsychobiology 56, 93–97. https://doi.org/10.1159/000111539 (2007).

Grah, M. et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a suicide factor in mental disorders. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 26, 356–363. https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2014.27 (2014).

Pinheiro, R. T. et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in women with postpartum affective disorder and suicidality. Neurochem. Res. 37, 2229–2234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-012-0851-9 (2012).

Huang, T. L. & Lee, C. T. Associations between serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels and clinical phenotypes in schizophrenia patients. J. Psychiatr. Res. 40, 664–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.11.004 (2006).

Park, Y. M., Lee, B. H., Um, T. H. & Kim, S. Serum BDNF levels in relation to illness severity, suicide attempts, and central serotonin activity in patients with major depressive disorder: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 9, e91061. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0091061 (2014).

Chen, Z. Y. et al. Variant brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Met66) alters the intracellular trafficking and activity-dependent secretion of wild-type BDNF in neurosecretory cells and cortical neurons. J. Neurosci. 24, 4401–4411. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0348-04.2004 (2004).

Kim, B. et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val/Met polymorphism and bipolar disorder. Association of the Met allele with suicidal behavior of bipolar patients. Neuropsychobiology 58, 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1159/000162356 (2008).

Iga, J. et al. The Val66Met polymorphism of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene is associated with psychotic feature and suicidal behavior in Japanese major depressive patients. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 144B, 1003–1006. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.b.30520 (2007).

Sarchiapone, M. et al. Association of polymorphism (Val66Met) of brain-derived neurotrophic factor with suicide attempts in depressed patients. Neuropsychobiology 57, 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1159/000142361 (2008).

Hong, C. J. et al. Association study of a brain-derived neurotrophic-factor genetic polymorphism and mood disorders, age of onset and suicidal behavior. Neuropsychobiology 48, 186–189. https://doi.org/10.1159/000074636 (2003).

Zarrilli, F. et al. Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) genetic polymorphism (Val66Met) in suicide: A study of 512 cases. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 150B, 599–600. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.b.30849 (2009).

Krabbe, K. S. et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 50, 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-006-0537-4 (2007).

Rozanska, O., Uruska, A. & Zozulinska-Ziolkiewicz, D. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 841. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21030841 (2020).

Beck, A. T., Kovacs, M. & Weissman, A. Assessment of suicidal intention: The Scale for Suicide Ideation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 47, 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343 (1979).

Nascimento, E. R., Maia, A. C., Soares-Filho, G., Nardi, A. E. & Cardoso, A. Predictors of suicidal ideation in coronary artery disease. Compr. Psychiatry 57, 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.10.017 (2015).

Kishi, Y., Robinson, R. G. & Kosier, J. T. Suicidal ideation among patients with acute life-threatening physical illness: Patients with stroke, traumatic brain injury, myocardial infarction, and spinal cord injury. Psychosomatics 42, 382–390. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.42.5.382 (2001).

Handley, T. E. et al. Suicidal ideation reported by adults with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes: Results from Diabetes MILES-Australia. Diabet. Med. 33, 1582–1589. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13022 (2016).

Petrak, F., Baumeister, H., Skinner, T. C., Brown, A. & Holt, R. I. G. Depression and diabetes: Treatment and health-care delivery. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 3, 472–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00045-5 (2015).

The Lancet Diabetes, E. Poor mental health in diabetes: Still a neglected comorbidity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 3, 393. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00144-8 (2015).

Matlock, K. A., Yayah Jones, N. H., Corathers, S. D. & Kichler, J. C. Clinical and psychosocial factors associated with suicidal ideation in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J. Adolesc. Health 61, 471–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.004 (2017).

Butwicka, A., Frisen, L., Almqvist, C., Zethelius, B. & Lichtenstein, P. Risks of psychiatric disorders and suicide attempts in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 38, 453–459. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-0262 (2015).

Dahlquist, G. & Kallen, B. Mortality in childhood-onset type 1 diabetes: A population-based study. Diabetes Care 28, 2384–2387. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.28.10.2384 (2005).

Batty, G. D., Kivimaki, M., Park, I. S. & Jee, S. H. Diabetes and raised blood glucose as risk factors for future suicide: Cohort study of 1 234 927 Korean men and women. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 66, 650–652. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2011-200464 (2012).

Koskinen, S. V., Reunanen, A. R., Martelin, T. P. & Valkonen, T. Mortality in a large population-based cohort of patients with drug-treated diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Public Health 88, 765–770. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.88.5.765 (1998).

Yamauchi, T. et al. History of diabetes and risk of suicide and accidental death in Japan: The Japan Public Health Centre-based Prospective Study, 1990–2012. Diabetes Metab. 42, 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2015.11.008 (2016).

Davis, W. A., Starkstein, S. E., Bruce, D. G. & Davis, T. M. Risk of suicide in Australian adults with diabetes: The Fremantle Diabetes Study. Intern. Med. J. 45, 976–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.12853 (2015).

Ola, M. S., Nawaz, M. I., El-Asrar, A. A., Abouammoh, M. & Alhomida, A. S. Reduced levels of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the serum of diabetic retinopathy patients and in the retina of diabetic rats. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 33, 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-012-9901-8 (2013).

Sun, Q. et al. Diagnostic significance of serum levels of nerve growth factor and brain derived neurotrophic factor in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Med. Sci. Monit. 24, 5943–5950. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.909449 (2018).

Autry, A. E. & Monteggia, L. M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol. Rev. 64, 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.111.005108 (2012).

Song, H. et al. Stress related disorders and risk of cardiovascular disease: Population based, sibling controlled cohort study. BMJ 365, l1255. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1255 (2019).

Jha, M. K., Qamar, A., Vaduganathan, M., Charney, D. S. & Murrough, J. W. Screening and management of depression in patients with cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73, 1827–1845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.041 (2019).

Posner, K. et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 168, 1266–1277. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 (2011).

Green, K. L. et al. The predictive validity of the Beck depression inventory suicide item. J. Clin. Psychiatry 76, 1683–1686. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09391 (2015).

Murrough, J. W. et al. Ketamine for rapid reduction of suicidal ideation: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 45, 3571–3580. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001506 (2015).

Kim, J. M. et al. Depression following acute coronary syndrome: Time-specific interactions between stressful life events, social support deficits, and 5-HTTLPR. Psychother. Psychosom. 86, 62–64. https://doi.org/10.1159/000449469 (2017).

Kim, J. M. et al. Effect of escitalopram vs placebo treatment for depression on long-term cardiac outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 320, 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.9422 (2018).

Kim, J. M. et al. Serotonin transporter gene association between anxiety and long-term cardiac outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71, 2706–2707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.006 (2018).

Kim, J. M. et al. Design and methodology for the korean observational and escitalopram treatment studies of depression in acute coronary syndrome: K-DEPACS and EsDEPACS. Psychiatry Investig. 11, 89–94. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2014.11.1.89 (2014).

Anderson, J. L. et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61, e179-347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.014 (2013).

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice, C et al. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 45, S17–S38. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-S002 (2022).

Marik, P. E. & Bellomo, R. Stress hyperglycemia: An essential survival response!. Crit Care 17, 305. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc12514 (2013).

Kim, J. M. et al. Determinants and escitalopram treatment effects on suicidal ideation in patients with acute coronary syndrome: Findings from the K-DEPACS and EsDEPACS studies. Int. J. Cardiol. 219, 225–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.048 (2016).

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J. & Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 4, 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004 (1961).

Killip, T. III. & Kimball, J. T. Treatment of myocardial infarction in a coronary care unit. A two year experience with 250 patients. Am. J. Cardiol. 20, 457–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(67)90023-9 (1967).

Montgomery, S. A. & Asberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br. J. Psychiatry 134, 382–389. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.134.4.382 (1979).

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by a grant of National Research Foundation of Korea Grant [NRF- 2020R1A2C2003472, NRF-2020M3E5D9080733] to Jae-Min Kim. Robert Stewart is part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. Robert Stewart is also a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study concept, design and interpretation of data were constructed by W.C. and J.-M.K. Statistical analysis was performed by W.C. and J.-M.K. Supervision was conducted by J.-W.K., H.-J.K., H.K.K., H.-C.K., J.-Y.L., S.-W.K., Y.J.H., Y.A., M.H.J., R.S., and J.-M.K. The data acquisition and analysis was conducted by W.C., J.-W.K., H.-J.K., J.-Y.L., S.-W.K., and J.-M.K. Drafting of the manuscript was made by W.C. and J.-M.K. All authors approved to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Jae-Min Kim declares research support in the last 5 years from Janssen and Lundbeck. Robert Stewart declares research support in the last 5 years from Roche, Janssen, GSK and Takeda. Sung-Wan Kim declares research support in the last 5 years from Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Allergan and Otsuka.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, W., Kim, JW., Kang, HJ. et al. Interaction effects of diabetes and brain-derived neurotrophic factor on suicidal ideation in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Sci Rep 12, 6602 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10557-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10557-6