Abstract

Postoperative management after transsphenoidal surgery (TSS) is important; however, the guidelines for resuming daily activities after TSS are insufficient. This study aimed to examine the time to return to activities of daily living (ADL) after TSS for pituitary tumors. A 4-month prospective data collection was completed for 114 of 117 patients who underwent TSS for pituitary tumors from April to July 2021. The time when the patient returned to ADL after surgery was measured using the self-recording sheet. More than 97% and 92% of the patients returned within 1 month (median: within 7 days) for the elements of basic ADL and within 2 months (median: within 15 days) for the elements of instrumental ADL, excluding a few. Notably, 73.3% of patients returned to work within 4 months. The median time for the activities included 64 days for washing hair head down, 44 days for blowing nose, 59 days for lifting heavy objects, and 102 days for sexual activity. For patients who received extended-TSS or had postoperative problems, the time to return was delayed. Based on these results, it will be possible to provide practical information and guidelines on the time to return to ADL after TSS in pituitary tumor patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transsphenoidal surgery (TSS) has remained the standard surgical treatment for pituitary adenoma (PA) since its introduction in the early 1900s, and its indications have been expanded to include lesions other than PA1. Although the outcomes of this surgical approach have improved over time, neurosurgical complications such as postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks or meningitis and endocrine dysfunction such as diabetes insipidus (DI) should be monitored1,2. The common reasons for 30-day readmission after TSS were epistaxis, hyponatremia, CSF leak, and other medical conditions, which added significant costs to the treatment3. Proper postoperative care and patient education are important to prevent and minimize the complications associated with TSS1,2,3.

Several patients inquire whether they can return to their daily lives after surgery, or when their function will return to the pre-operative levels. Patients anticipated a cure after TSS and were satisfied with the surgical results. Several patients reported receiving adequate perioperative information; however, half of them felt that they had not received adequate postoperative information. Some aspects of post-TSS care still need improvement4.

Based on previous studies on the time to return to activities of daily living (ADL), a consensus was reached among pituitary surgeons on the recommendations for the time to return to specific activities after TSS5. Other than that, the return-to-work rates were measured, and a few behavior guidelines were introduced as part of the recovery protocol after TSS6,7,8. Research on the time to return to comprehensive and specific ADL after TSS is insufficient. It is necessary to prepare a basis for reducing the postoperative complications after TSS, resolving uncertainty about the postoperative recovery process, and helping them to return to their specific, practical, and comprehensive ADL in the safest and fastest time after TSS. Therefore, this study aimed to present the basic data needed to provide information and guidelines for the appropriate return time by examining the time to return to ADL after TSS in patients with pituitary tumors.

Results

General and clinical characteristics

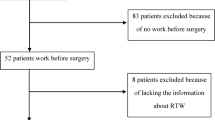

From April to July 2021, a total of 117 consecutive patients underwent TSS for a pituitary tumor at the Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, Korea. Of a total of 117 patients, 116 were enrolled in the study, of whom 114 completed data collection and were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). One patient was excluded due to postoperative hemorrhage, and 2 patients were discontinued due to a brain abscess and the patient's request for withdrawal. At baseline, the means of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-Performance Status (ECOG-PS) and Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) for the patients were 1 (median 1; range 1–2) and 80 (median 80; range 70–80), respectively. Table 1 presents the demographic data and clinical characteristics of patients who underwent TSS for a pituitary tumor. The mean age at the time of surgery was 52.4 years (range 21–80 years), and the patients included 57 men and 57 women. Among the patients, 91 (79.8%) worked before surgery. In terms of the histological type, PA was the most common in 94 patients (82.4%) followed by craniopharyngioma in nine patients (7.9%). According to the surgical approach, 89 patients (78.1%) received standard-TSS and 25 patients (21.9%) received extended-TSS and intraoperative CSF leak was observed in 49 patients (43.0%). Postoperative problems included CSF leak (1 patient, 0.9%), epistaxis (5 patients, 4.4%), hypopituitarism (14 patients, 12.3%), DI (14 patients, 12.3%), and syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (3 patients, 2.6%).

Time to return to ADL after surgery

In the elements of BADL, 50% of the patients took 5 days to wash their hair head up, approximately two months to wash their hair head down, approximately 1.5 months to blow their nose, approximately 2 months to lift/carry/move objects weighing more than 10 kg, and approximately 100 days to engage in sexual activity (Fig. 2, Table 2). Among the representative BADL elements (excluding lifting/carrying/moving objects, and sexual activity), more than 97% of the patients returned to performing them within 1 month (median: within 7 days). Lifting/carrying/moving objects > 10 kg, and sexual activity were not resumed by 16.8% and 42.4% of the patients, respectively, until 4 months after surgery (Table 2).

In the elements of IADL, 50% of the patients took approximately 1 month to begin part-time work, approximately 2 months to work 8 h a day, approximately 110 days to climb mountains and jog/run, and 19 days to drive a car. Only 6.6% of the patients resumed air travel within 4 months (Fig. 2, Table 2). Among the representative IADL elements, more than 79% of the patients resumed within 1 month, and more than 92% resumed within two months for elements excluding work, social activities, leisure, and driving a car (median values: within 15 days). Of the patients, 73.3% resumed working 8 h/day within 4 months. Regarding part time/work (8 h/day) and social activities, 16.5/26.7% and 25.5% of the patients, respectively, did not resume until 4 months after surgery. Also, when it comes to leisure and driving a car, 4.6–100.0% and 4.9% of the patients, respectively, did not resume until 4 months after surgery. Additionally, the median time for the activities included after 4 months for wind instrument, 17 days for using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), 6 days for drinking coffee/tee, and 49 days for complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) (Table 2).

Difference in the time to return to ADL according to clinical characteristics

Upon looking at the difference in the time to return to ADL after surgery according to the clinical characteristics of patients who underwent TSS for a pituitary tumor (Table 3), the patients who received extended-TSS were all slower than those who received standard-TSS for the activities mentioned below: walking (p = 0.021), washing hair head up (p < 0.001), taking a shower (p = 0.003), dressing (p = 0.014), climbing stairs (p = 0.001), toilet use (p = 0.033), self-care in general (p = 0.048), grooming (p = 0.013), transferring (p = 0.005), finances and administration (p = 0.029), using modern appliances (p = 0.007), and managing own medication (p = 0.009). Patients with postoperative problems were slower than those without them, for walking (p = 0.002), washing hair head up (p = 0.001), taking a shower (p = 0.001), dressing (p = 0.004), having a meal (p = 0.002), climbing stairs (p = 0.035), toilet use (p = 0.004), transferring (p < 0.001), communicating/expressing (p = 0.004), using modern appliances (p = 0.003), and managing own medication (p = 0.038), while were faster for climbing mountains (p = 0.032).

The time taken to resume the following activities (among BADL) is described as follows: older patients at the time of surgery (p = 0.044) and patients who had a previous TSA/craniotomy (p = 0.005) resumed “washing their hair head-down” earlier than younger patients and those who did not. Patients who had a previous TSA/craniotomy resumed “blowing their nose” earlier than those who did not (p = 0.042), whereas patients who underwent a transseptal approach took longer than those who underwent an endonasal approach (p = 0.005). “Lifting/carrying/moving objects” was resumed sooner in men than in women (p = 0.009), and sexual activity took longer in patients who had an intraoperative CSF leak than in patients who did not (p = 0.022). The time taken to resume the following activities (among IADL) is described as follows: patients who had a previous TSA/craniotomy resumed work (8 h/day) earlier than those who did not (p = 0.027), and men resumed non-physical work earlier than women (p = 0.010). Men took longer to “climb mountains” than women (p = 0.002), whereas patients with postoperative problems resumed earlier than those without (p = 0.032). “Driving a car” was resumed sooner in men than in women (p = 0.009) and in patients who had a previous TSA/craniotomy than in those who did not (p = 0.049).

Discussion

This study attempted to present the basic data to provide information and guidelines on the “appropriate return period,” to the medical staff and patients by examining the time to return to ADL after TSS for a pituitary tumor. With the exception of lifting/carrying/moving objects and sexual activity, more than 97% of patients were observed to resume BADL within one month for most elements whereas for most elements of IADL, it took up to two months for more than 92% of the patients, with the exception of work, social activities, leisure, and driving a car. The results from another study showed that the disease burden, mental and physical functioning, and visual functioning improved within 6 weeks after pituitary tumor surgery6. Additionally, the guidelines recommended by the German pituitary working group reported that all elements of daily activity, sports, and occupation can be implemented within 3 months after surgery5; however, patients included in this study had a late return to ADL. More patients than expected independently decided when to return to the activities. Based on the results of this study, it is possible to prevent the patients from returning too early for elements that may be risky. Conversely, the patients who delay their return may be encouraged to return faster on the basis that no special problems have occurred in patients who returned earlier. Moreover, in this study, it can be observed that there was a difference in the time to return after surgery depending on factors, such as the extended- or standard-TSS and the presence or absence of postoperative problems. In particular, it should be considered that the return time is delayed in the case of extended-TSS compared to the case of standard-TSS.

The time to return to the individual elements reported in this study was compared with the recommended time suggested by the German pituitary working group. The working group suggested that intraoperative CSF leak, intracranial air, hyponatremia, and brain surface involvement by tumor or resection should be checked, adding that the recommendations indicate the minimum time interval after surgery5. In this study, the median value for “washing hair head up” was 5 days, and it was related to the histological type of the tumor, standard/extended-TSS, postoperative problems, and lumbar drainage or steroid usage after surgery. It is similar to the recommended “hair washing time” of less than 1 week. Of the work elements, a crucial patient-centered outcome parameter, the median value of time to return to “8-h work per day” was approximately two months, and difference was present depending on the past surgical history. The recommended time was 2–3 weeks for non-physical work and 4–6 weeks for physical work. The patients in this study returned to the median value of approximately 1 month for both non-physical and physical work, slightly later in the former and slightly earlier in the latter compared to the recommended time. The time to return to non-physical work was related to the sex. According to the results, 86% of patients who had a job before surgery remained employed after 6 months6 and there was no effect on the long-term follow-up compared to the general population for returning to work9. It might be necessary to investigate by extending the follow-up period. In the case of “mountain climbing,” which applied to the most patients in the sports elements, it was performed at the median value of 106 days, and sex and postoperative problems were related factors. Compared to the 3–12 week recommendation for all sports, the return was delayed. In the case of driving, it was implemented at the median value of 19 days, which is also slightly delayed compared to the 1–2 week recommendation. In this study, it differed according to the sex and past surgical history of the individual.

In addition, the timing of washing hair head down (median value of 64 days), blowing nose (44 days vs. 3–4 weeks), lifting heavy objects (59 days vs. 4–6 weeks), sexual activity (102 days vs. 1–2 weeks), wind instrument (after 4 months vs. 6 weeks), and using CPAP (17 days vs. 3–4 weeks) were different from the recommended guidelines. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a new guideline by reviewing and negotiating the surgeon’s opinions and patient’s perspective from various angles. This will provide useful information about the possible return period for ADL, including elements that patients are actually curious about in the clinical field, such as drinking coffee/tea, air travel, and CAM therapy.

This study had the following limitations. First, although the performance status did not clearly deteriorate below the criterion during the study period, the time to return may have been somewhat delayed, as we included some patients who were in various conditions and showed slow recovery and temporary deterioration of their status. Second, it should be taken into account that there was a difference in the understanding of the elements depending on the patient. Third, it may have been measured conservatively because the patients were asked to write down the time when it was executed rather than the time when it was judged that it is possible, and there was a tendency for patients to hesitate or to delay by caregivers. Fourth, the responses may be limited due to the effect of time limit, seasonal factors, and the COVID-19 situation. In particular, there is a possibility that it may not have been completed for elements, such as sports or air travel. This should be taken into account when interpreting the results, and it is suggested to extend the postoperative follow-up period in the future. Improvements are needed in research methods and processes, such as reorganizing the tool and computerizing the survey methods in consideration of extending the follow-up period. Nevertheless, this research activity is an initial effort to understand the recovery process after TSS in pituitary tumor patients, and the results of this study can be used as the basic data to provide daily life management guidelines for pituitary tumor patients after TSS.

Conclusions

The time to return with respect to various elements of ADL was measured after pituitary tumor surgery. Additionally, the time to return was different for each patient and varied according to several factors. Based on these results, it will be possible to provide practical information and guidelines on the time to return to ADL after TSS in pituitary tumor patients. Moreover, it will maintain the function and well-being of daily life after surgery by reducing the post-surgical complications, uncertainty about recovery and daily life, and helping patients return to their daily life in a timely manner.

Methods

We conducted a prospective study to assess the timing of return to ADL after TSS for a pituitary tumor. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Samsung Medical Center (Study number: 2021-03-113), and written informed consent was obtained from all the patients. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) Age ≥ 18 years; (b) Histologically confirmed tumor; (c) Patients who underwent tumor removal by TSS; (d) ECOG-PS ≤ 2 or KPS ≥ 70 at discharge after surgery; (e) Patients with no communication problems, who understood the purpose of the study, and consented to participate; (f) Performance status did not worsen below the criterion during the study period; (g) No re-TSS or craniotomy was performed for tumor progression/recurrence or residual tumors during the study period. Patient education on daily life was carried out before discharge. As per our established protocol, we recommended that patients should avoid certain activities such as work with heavy physical activity, hair washing with head down, air plane boarding, blowing the nose and sneezing for a duration of 1 or 3 months following TSS. At an outpatient visit, the patient was allowed to resume these activities as deemed appropriate by their outpatient physician. The outpatient physician made a comprehensive assessment of the presence or absence of postoperative complications, surgical approach, postoperative blood sampling results, etc., and indicated to each patient when he or she could return to each ADL.

Electronic medical records were reviewed to collect general and clinical characteristics of the patients. A self-recording sheet was developed to measure when patients returned to ADL after surgery, minimizing the recall period. The ADL elements in the self-recording sheet were constructed reflecting the clustered list of basic and instrumental activities by Oort et al.10 and the detailed list of activities provided on the websites of 27 hospitals or institutions. The ADL were broadly classified into 15 elements of “basic” ADL (BADL) and 31 elements of “instrumental” ADL (IADL), with each element presented in order of the measurement frequency. It was divided into sub-activities for four BADL elements and four IADL elements, with 35 elements and 50 elements, respectively, for a total of 85 elements. BADL included activities that enable basic survival and well-being, such as bathing, dressing, eating, and using the toilet, while IADL included more complex activities than BADL, such as housekeeping, grocery shopping, managing finances, phone calls, and taking medication. The content validity of the developed self-recording sheet was evaluated by a group of five experts: one neurosurgeon, two head nurses in the neuro ward, one coordinator, and one physician assistant. As a result, the scale-level content validity index using the universal agreement method (S-CVI/UA) was 0.78, and the scale-level content validity index using the averaging method (S-CVI/Ave) was 0.94. The item-level content validity index (I-CVI) ranged from 0.60 to 1.00.

It was designed to input the return time for each ADL element. The “time to return to ADL” referred to the time elapsed after surgery until the point in time when resumption of preoperative ADL became possible postoperatively. If the activities had not been performed before surgery and there was no plan to perform them in the future, they were marked as “not applicable.” In this study, we collected self-reported sheets that documented the patients' ADL return times from April to November 2021. At discharge and at 1, 2, 3, and 4 months after surgery, it was checked whether the patient had written the execution time for each ADL element, and the missing parts were encouraged to be filled in. A copy of the sheet was kept at discharge and one month after surgery (at the time of visit) to reprovide in case of loss, and the final sheet was retrieved four months after surgery. When a hospital visit was scheduled, the patient was contacted in advance to remind them to fill and bring the self-recording sheet.

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA). The general and clinical characteristics were expressed as numbers and percentages or mean and standard deviation. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and percentile of time to return were performed to assess the time to return to ADL. In addition, the number and percentage of each period were obtained to evaluate the ADL return rate by period after surgery. For the difference in the time to return to ADL according to the general and clinical characteristics, the Mann–Whitney U test, Kruskal–Wallis test, independent samples t-test, ANOVA, and Spearman correlation were used after a normality test using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. The statistical analyses were guided by a statistician.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Miller, B. A., Ioachimescu, A. G. & Oyesiku, N. M. Contemporary indications for transsphenoidal pituitary surgery. World Neurosurg. 82, S147-151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2014.07.037 (2014).

Berker, M. et al. Complications of endoscopic surgery of the pituitary adenomas: Analysis of 570 patients and review of the literature. Pituitary 15, 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-011-0368-2 (2012).

Hendricks, B. L., Shikary, T. A. & Zimmer, L. A. Causes for 30-day readmission following transsphenoidal surgery. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 154, 359–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599815617130 (2016).

Edem, I. J. et al. A prospective qualitative study on patients’ perceptions of endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery. Br. J. Neurosurg. 27, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.3109/02688697.2012.711497 (2013).

Knappe, U. J. et al. Consensus on postoperative recommendations after transsphenoidal surgery. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 127, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0664-7710 (2019).

Lobatto, D. J. et al. Toward value based health care in pituitary surgery: Application of a comprehensive outcome set in perioperative care. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 181, 375–387. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-19-0344 (2019).

Cote, D. J., Iuliano, S. L., Catalino, M. P. & Laws, E. R. Optimizing pre-, intra-, and postoperative management of patients with sellar pathology undergoing transsphenoidal surgery. Neurosurg. Focus 48, E2. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.3.FOCUS2043 (2020).

Hughes, M. A. et al. Enhanced recovery and accelerated discharge after endoscopic transsphenoidal pituitary surgery: Safety, patient feedback, and cost implications. Acta Neurochir. (Wien.) 162, 1281–1286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-020-04282-0 (2020).

Uvelius, E. et al. Quality of life and work capacity are unrelated to approach or complications after pituitary surgery. World Neurosurg. 108, 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.08.087 (2017).

Oort, Q. et al. Evaluation of the content coverage of questionnaires containing basic and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL) used in adult patients with brain tumors. J. Neurooncol. 143, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-019-03136-9 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Department of Nursing at Samsung Medical Center for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and D.K. designed this study. J.L., E.T., H.L., S.O., H.S. and H.C. contributed to collect patients’ data. J.L. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, JA., Tak, EY., Lim, H.L. et al. Time taken to resume activities of daily living after transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary tumors. Sci Rep 13, 4132 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31203-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31203-9