Abstract

Gold nanodendrite (AuND) is a type of gold nanoparticles with dendritic or branching structures that offers advantages such as large surface area and high conductivity to improve electrocatalytic performance of electrochemical sensors. AuND structures can be synthesized using electrodeposition method utilizing cysteine as growth directing agent. This method can simultaneously synthesize and integrate the gold nanostructures on the surface of the electrode. We conducted a comprehensive study on the synthesis of AuND on screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE)-based working electrode, focusing on the optimization of electrodeposition parameters, such as applied potential, precursor solution concentration, and deposition time. The measured surface oxide reduction peak current and electrochemical surface area from cyclic voltammogram were used as the optimization indicators. We confirmed the growth of dendritic gold nanostructures across the carbon electrode surface based on FESEM, EDS, and XRD characterizations. We applied the SPCE/AuND electrode as a nonenzymatic sensor on ascorbic acid (AA) and obtained detection limit of 16.8 μM, quantification limit of 51.0 μM, sensitivity of 0.0629 μA μM−1, and linear range of 180–2700 μM (R2 value = 0.9909). Selectivity test of this electrode against several interferences, such as uric acid, dopamine, glucose, and urea, also shows good response in AA detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gold nanodendrite (AuND) is a type of gold nanoparticles morphology often applied to electronic devices and sensors due to its advantages, such as a large number of active sites, large working surfaces, and high conductivity1,2. Gold nanodendrite (AuND) is a nanometer-sized gold crystal structure consisting of many dendritic branches with numerous active sites on their surface, including tips, kinks, ledges, steps, and sharp edges2. These active sites are surface defects at the microscopic level resulting from the growth process of the gold nanoparticle structures3. AuND can be synthesized using the electrodeposition method, an electrochemical technique that utilizes electric current to deposit a metal layer on a conductive substrate4. This method has several advantages as it is easy, inexpensive, and environmentally friendly2,5. It does not require surface-active agents, has a good scalability, can operate at room temperature, and can yield high-purity particles because it allows selective deposition of specific elements or compounds from the precursor solution. Using electrodeposition method, the growth of the gold dendritic structures can be done quickly, directly, and controllably on the surface of the electrode, enabling high-precision synthesis or growth of materials at specific desired locations.

One mechanism of electrodeposition that can yield a dendritic structure is the use of L-cysteine or L-cys as an organic growth-directing agent during the deposition process6,7. L-cysteine adsorbs onto gold surfaces or polycrystalline Au (poly Au) through its thiol (–SH) moiety, forming a strong Au–S bond. Thiol-mediated attachment or detachment on gold crystal planes is potential-dependent. Therefore, during an electrodeposition process in which a specific potential is used, L-cys will not cover the entire surface of the initially growing gold structures, but only specific crystal planes. In this study, a specific electrodeposition potential is used so that L-cys will detach only from the (111) crystal plane. This results in an anisotropic growth of the Au particles that occur only in the direction of the (111) plane. The gold nanostructure growing on the (111) plane will become dendritic nanostructures.

The (111) crystal plane of Au has several interesting properties. It is the only crystal plane of the face-centered cubic crystal structure of metal that can undergo surface reconstruction at room temperature8,9. Au(111) is well-known for its ability to easily interact with thiol groups, so it is used as a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) substrate10, as in the case of AuND growing mechanism in this study which uses L-cys as the growth directing agent. Au(111) can also be used for the substrate where low-dimensional material (like carbon nanoribbon) can grow, and the substrate for chemical or physical properties exploration of various absorbents11.

AuND has been widely implemented in sensor technology due to its beneficial properties. There have been several studies that utilize AuND to modify electrodes in electrochemical sensors1,2,7,12,13,14,15,16. However, studies that specifically modify screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) with AuND for sensing applications are still rare. In fact, there is only a study from 2017 by Sorouri and colleagues1 which used AuND-modified SPE for an immunosensor. Other studies mainly used glassy carbon electrode (GCE) or other types of electrodes which require a conventional three-electrode system. SPE is a type of electrode that unifies and miniaturizes three-electrode system (working, reference, and counter electrodes) onto a single printed strip17. This results in a smaller and more portable electrode that is beneficial for point-of-care detection applications18, faster detection, and the ability to perform the diagnostic tests closer to the patients19 as point-of-care detection removes the need for a full laboratory setup. There is an untapped potential for AuND-modified SPEs for point-of-care applications which will be addressed in this work.

Ascorbic acid (AA) or commonly known as vitamin C, plays many important roles in the human body such as in the development and maintenance of connective tissue, bone formation, wound healing, metabolic functions, antioxidants, immune system protection, and therapeutic agents20. In recent years, there have been several studies on electrochemical sensors/biosensors for detecting ascorbic acid based on gold nanoparticles (AuNP)21,22,23,24,25. However, there is no study that specifically mentions the use of gold nanodendrite (AuND) synthesized by electrodeposition for this sensing application. There is a 2013 study by Zheng and colleagues, which developed a non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor for detecting ascorbic acid and dopamine based on AuNPs synthesized by electrodeposition. However, the AuNPs morphology was floral or flower-like22. Meanwhile, in the 2013 study by H. Zhang and colleagues, an ascorbic acid sensor based on gold nanoparticles with a dendritic nanoflower-like structure was developed, but the synthesis method used was based on aniline vapor23. Besides, although their gold nanoparticles have a dendritic shape, the morphology of the gold nanodendrite produced is different from the structure of the gold nanodendrite intended in this study.

Therefore, in this study, we comprehensively optimized the synthesis of AuND using the electrodeposition process on the surface of carbon-based SPE, or SPCE (screen-printed carbon electrode), on several aspects. Then, we implemented the modified electrode as a non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor to detect ascorbic acid (AA) by evaluating several important performance parameters, such as LOD, LOQ, sensitivity, durability, and selectivity, for future point-of-care applications.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

Gold(III) chloride trihydrate (HAuCl4.3H2O) ≥ 99.9%, sulfuric acid (H2SO4) 95–97%, L-cysteine (C3H7NO2S) 97%, nitric acid (HNO3) 65%, L-ascorbic acid (C6H8O6) ≥ 99.7%, dopamine hydrochloride (C8H12ClNO2) 98%, urea (CH4N2O) 99.0–100.5%, uric acid (C5H4N4O3) ≥ 99%, and D(+)-glucose anhydrous (C6H12O6) 97.5–102.0% were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Sodium dihydrogen phosphate dihydrate (NaH2PO4.2H2O) 98% and potassium hexacyanoferrate(III) (K3[Fe(CN)6]) 98% were obtained from Loba Chemie (Mumbai, India). Sodium phosphate dibasic dodecahydrate (Na2HPO4.12H2O) 98% was obtained from Pudak Scientific (Bandung, Indonesia). All the above chemicals mentioned were analytical grade. Additionally, for preliminary real sample study, CDR® multivitamin supplement from Bayer (Leverkusen, Germany) was used.

Apparatus and instrumentations

The electrodes used were hyper-value screen-printed carbon electrodes (HV-SPCEs) purchased from Zimmer & Peacock, Ltd. (Coventry, UK). The electrodes were made of carbon (C) for the working electrode (WE), silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) for both the reference electrode (RE) and the counter electrode (CE), silver (Ag) for the contact pad, and UV photoresist ink for the dielectric coating, all printed on a surface of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate. The electrochemical procedures (electrodeposition and electrochemical analysis) were carried out using Ana Pot EIS potentiostat from Zimmer Peacock, Ltd (Coventry, UK) with PSTrace software from PalmSens (Houten, the Netherlands). For material characterization procedures, field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) characterization were performed using JIB-4610F electron microscope from JEOL, Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). X-ray diffraction (XRD) crystallography was performed using a SmartLab X-ray diffractometer from Rigaku (Tokyo, Japan). For data analysis, OriginPro software (Northampton, Massachusetts, USA) was used.

Methods

Four main experiments were conducted in this study, (i) gold nanodendrite synthesis via electrodeposition, (ii) electrochemical characterization of the electrodes, (iii) material characterization, and (iv) application of the electrodes for ascorbic acid detection.

Gold nanodendrite synthesis using electrodeposition method

Before the electrodeposition process or any electrochemical measurements were conducted, all bare electrodes were first electrochemically activated. The procedure is illustrated in Fig. 1a. A 100 μL droplet of 0.5 M H2SO4 was placed onto the working surface of the bare SPCE using a micropipette until all parts of the WE, RE, and CE were covered with the droplet. Next, cyclic voltammetry (CV) was carried out with a sweep potential from 0.9 to 1.5 V vs Ag/AgCl, a step potential of 0.01 V, a scan rate of 0.1 V s−1, and three cycles of CV. This activation procedure is based on our previous study26. After the procedure was completed, the SPCE surface was rinsed with distilled water and then dried by blowing air using a rubber blower.

The diagrams of several experimental procedures conducted in this study, namely (a) the activation of the bare electrode; (b) the electrodeposition process to synthesize AuND on the surface of SPCE’s working electrode; and the electrochemical characterization of the SPCE-AuND in 0.5 M H2SO4 using (c) a droplet-based sample and (d) immersion of the electrode in 1500 µL microtube sample container.

The electrodeposition process of AuND on the WE surface of the SPCE was conducted using the constant potential amperometry (CPA) technique in a deposition solution containing HAuCl4.3H2O, H2SO4, and L-cysteine. Several parameters of the electrodeposition process were optimized to grow the optimal AuND structures. Before the optimization process, an initial electrodeposition trial experiment based on a reference study by Ren et al.7 was conducted. In the initial trial experiment, the parameters used were the same as in the reference study except for the type of electrode (SPCE was used instead of GCE) and deposition time (1500 s deposition time was used, while in reference 1000 s, 2000 s, and 3000 s were used). The deposition solution (550 µL) consisting of 1 mM HAuCl4 + 0.1 mM L-cys + 0.5 M H2SO4 (all dissolved in distilled water) was prepared and put into a microtube. The mixing order of the chemicals was as follows: distilled water, L-cys (aq), H2SO4 (aq), and finally HAuCl4 (aq). Next, the activated SPCE was installed to the connector from the potentiostat in a vertical position (see Fig. 1b). The microtube containing the deposition solution was then attached to the SPCE so that all parts of the SPCE electrode were immersed into the solution. After that, constant potential amperometry (CPA) was run with a deposition potential of − 0.8 V vs Ag/AgCl, a time interval of one second, and a deposition time of 1500 s. When finished, the surface of the AuND modified SPCE (or SPCE-AuND) was rinsed using distilled water and then dried using a rubber blower to remove any residue from the deposition process.

During the initial trial experiment, an initial optimization experiment was also carried out by increasing the concentration of HAuCl4 used in the deposition solution to 5 mM. However, it was found that bubbles appeared on the surface of the electrode that disturbed the electrodeposition process (this will be elaborated further in the results and discussion section, see also Figure S1 in the supplementary information). To prevent bubble formation, several parameter adjustments were made, such as lowering the concentration of H2SO4 from 0.5 M to 0.1 M and reducing the deposition time from 1500 to 1000 s, the shortest deposition time used in the reference study by Ren et al.7. The initial trial experiment was then repeated with these changes in the parameters.

For the optimization of the electrodeposition process, the same procedure and parameters as the final trial experiment were applied, with the parameters of deposition potential, deposition solution concentration (specifically HAuCl4 concentration), and deposition time optimized respectively. There was also an adjustment of the microtube used to contain the deposition solution during the deposition time optimization process which will be explained further in the result and discussion. All experiments in this section were conducted at room temperature.

Electrochemical characterization

Electrochemical characterization using sulfuric acid (H2SO4) was carried out after the bare SPCE had been modified with AuND. The aim of this procedure was to measure the surface oxide reduction (SOR) peak current and to calculate the electrochemical surface area (ECSA) of the modified electrode. The SOR peak current and ECSA data were then used as the indicators to evaluate electrodeposition parameters during the optimization process. The ECSA value needs to be investigated since it is related to the number of active sites on the SPCE-AuND surface which play a role in increasing the electrocatalytic performance of the electrode against the analyte when applied as an electrochemical sensor13,27. Almost every gold nanoparticle-based biosensor study conducts this typical characterization process since the specific peak of the surface oxide reduction is easy to observe7,13,16,28. The procedure of the electrochemical characterization is similar to the electrode activation procedure (Fig. 1c). A 100 µL droplet of 0.5 M H2SO4 was placed onto the working surface of SPCE-AuND, which was installed to the connector from the potentiostat (ensuring all WE, RE, and CE covered). Then, slightly different from the activation process, CV was carried out with a sweep potential from 0.4 to 1.5 V vs Ag/AgCl, a potential step of 0.01 V, a scan rate of 0.05 V s−1, with three cycles of CV. When finished, the SPCE-AuND was rinsed with distilled water and then dried using a rubber blower.

There were also parameter adjustments of electrochemical characterization conducted during the electrodeposition optimization process. The first adjustment was to change the sweep potential range of CV from 0 to 1.2 V vs Ag/AgCl (initial potential from 0 V vs Ag/AgCl). This adjustment was necessary because a potential shift in the surface oxide reduction peak was observed during deposition time optimization, causing the peak to be invisible using the previous range. Additionally, during the final consideration of optimal parameter decision and repeatability testing of the optimal SPCE-AuND over 25 cycles of CV in H2SO4, an adjustment in the H2SO4 sample volume was made. Instead of using a droplet sample, a 1500 µL sample of 0.5 M H2SO4 was put into a microtube and used for SPCE-AuND electrochemical characterization, as seen in Fig. 1d.

At the end of the electrodeposition optimization, the electrochemical performance of the optimal SPCE-AuND was compared with the bare SPCE using CV in K3[Fe(CN)6]. This performance test aimed to observe any increase in the redox peak of the reaction and any change from peak-to-peak separation between bare SPCE and SPCE-AuND as also done by Das et al.16. The procedure for this test was similar to the previous electrochemical characterization (Fig. 1c), but the CV parameters used were a sweep potential from − 0.6 to 0.6 V vs Ag/AgCl, a potential step of 0.01 V, a scan rate of 0.05 V s−1, and three cycles of CV. The sample used was 5 mM K3[Fe(CN)6] dissolved in 50 mM PB pH 5. All experiments in this section were conducted at room temperature.

Material characterization

Material characterizations were carried out using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) crystallography. These methods confirmed the formation of the gold nanodendrite structure on the WE surface of the SPCE. FESEM analysis was performed to observe the morphological structures of AuND synthesized during the deposition time parameter optimization process. EDS analysis determined the elemental composition of the modified working electrode surface of the optimally synthesized SPCE-AuND. XRD was used to analyze the crystal planes of the optimally synthesized SPCE-AuND. Due to instrumentation limitations, XRD characterization could not be conducted only on the surface of the working electrode and had to be done on the entire surface of the SPCE-AuND. Therefore, the data obtained contains many background interferences from the other parts of the SPCE.

Ascorbic acid detection

The main goal of this step was to determine the sensitivity and the selectivity of the optimally synthesized SPCE-AuND in detecting ascorbic acid (AA) samples. This step consists of four stages: (i) initial testing to find the AA oxidation peak, (ii) AA diffusion-controlled reaction validation, (iii) measurement of AA detection sensitivity performance, and (iv) AA detection selectivity test. All experiments in this section were conducted at room temperature.

Before the modified electrode was used to detect AA, a cleansing process of the optimal SPCE-AuND using constant potential amperometry in the HNO3 sample was conducted. The cleansing process is performed to remove L-cys (from the electrodeposition process) from the surface of the electrode before it is used to detect the analyte. This procedure is adapted from the study by Ren et al.7 with slight modifications to concentration and potential used. A 100 µL sample of 0.025 M HNO3 solution was dropped onto the surface of freshly electrodeposited SPCE-AuND. The solution should cover all three electrodes (WE, RE, and CE). Next, a constant potential amperometry (CPA) with a potential of − 0.8 V vs Ag/AgCl was applied for 120 s. The SPCE-AuND was then rinsed with distilled water and dried using a rubber blower. This procedure was then followed by a second cleansing process using 0.5 M H2SO4, following the same procedure as the electrochemical characterization in Fig. 1c. The second cleansing procedure was added since the modified electrode showed a cleaner AA detection response if this procedure was also conducted. Cleaning the electrode using cyclic voltammetry in H2SO4 solution has been conducted in several gold-based electrochemical sensors studies. In the study by Zakaria et al.28, this procedure is mentioned as a “cleaning” method in addition to the ECSA determination method. Meanwhile, in the study by Steel et al.29, the cleaning process using CV in H2SO4 solution was carried out before the gold-based electrode was used as a biosensor. After this cleansing process was conducted, the modified electrode could be used to detect AA.

The first stage of the AA detection experiment was the initial testing to find the AA oxidation peak. The oxidation reaction of AA was favored because of the ease of ascorbic acid oxidation to dehydro-ascorbic acid30, so AA oxidation peaks were widely used in research on AA biosensors31,32. The supporting electrolyte used for the AA detection in this study was 50 mM Gomori Phosphate Buffer (PB) pH 5 with a concentration of 50 mM, based on several references33,34,35,36,37. The acidity of pH 5 was used since AA tends to be more stable and sensitive in an acidic solution with pH ≤ 5.438. Using a solution in a higher pH range (alkaline) tends to make AA more unstable37. A solution with a pH lower than 5 was not preferred in the study by Stozhko et al.36 due to the presence of an interfering signal. Turkusic et al.39. also avoided using a more acidic solution because it can damage the electrode. The PB pH 5 was prepared by dissolving NaH2PO4.2H2O and Na2HPO4.12H2O in distilled water. To find the oxidation peak of AA, cyclic voltammetry (CV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) techniques were carried out in 0 and 1800 µM AA solution (in 50 mM PB pH 5) dropped on the working surface of the optimal SPCE-AuND (the configuration is the same as in the Fig. 1c). The parameters of the CV used were a sweep potential from − 0.5 to 0.5 V vs Ag/AgCl (initial potential from 0 V vs Ag/AgCl), a potential step of 0.01 V, a scan rate of 0.05 V s−1, and three cycles of CV. The parameters of the DPV used were a potential range from − 0.5 to 0.5 V vs Ag/AgCl, a potential of step of 0.01 V, a pulse potential of 0.1 V vs Ag/AgCl, pulse interval of 0.02 s, and a scan rate of 0.05 V s−1.

The second step is AA diffusion-controlled reaction validation. The diffusion-controlled reaction of an electrochemical sensor can be validated using the CV method by varying the scan rate value used40. In this study, the validation was carried out by performing several CVs in 3600 µM AA (in 50 mM PB pH 5) dropped on the working surface of the optimal SPCE-AuND. This procedure is based on the studies by Amin et al. (2021) and Raj et al.41,42, with several adjustments to AA concentration, supporting electrolyte, and scan rate values used. The CV parameters used were a sweep potential from − 0.6 to 0.2 V vs Ag/AgCl, a potential step 0.01 V, and the scan rate was varied from 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 150, 200, to 250 m V s−1. The CV anodic peak current for each scan rate variation was then plotted against the square root of the corresponding scan rate value, and its linearity was analyzed. The experimental configuration of this study is the same as in Fig. 1c.

The third stage is the measurement of AA detection sensitivity to obtain performance values such as linear range, limit of detection (LOD), and limit of quantification (LOQ). Measurements were carried out using several variations of AA concentration in 50 mM PB pH 5, namely 0, 180, 360, 450, 900, 1350, 1800, and 2700 µM. Measurements were made using differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) method with a potential range from − 0.4 to 1 V vs Ag/AgCl, a potential of step 0.01 V, a pulse potential of 0.1 V vs Ag/AgCl, a pulse interval of 0.02 s, and a scan rate of 0.05 V/s. The sample volume used was 100 µL dropped onto the surface of the optimally electrodeposited SPCE-AuND. The solution should cover all three electrodes (WE, RE, and CE) (the configuration is the same as in Fig. 1c). Measurements were taken one by one for each concentration variation, starting from the lowest concentration to the highest. After each measurement was completed, the SPCE-AuND was rinsed with distilled water and then dried using a blower. An additional preliminary real-sample study using CDR® multivitamin supplement was conducted using the same method as the sensitivity test. The CDR® was dissolved in 50 mM PB pH 5 with the respect of vitamin C concentration contained there. It was diluted until the vitamin C concentration was 360, 1350, and 2700 µM. The sensor was then used to detect these varied concentrations of AA (vitamin C) in the CDR® solution. The durability of the sensor was also tested by conducting DPV method with the same measurement parameters used in the sensitivity test. One SPCE-AuND was used in this test to detect 2700 µM AA (dissolved in 50 mM PB pH 5) on day 1, 4, 8, 15, and 28 after the fabrication process of the electrode. The electrode was rinsed with distilled water after being used each day. A fresh sample of AA was also prepared for each day.

The last stage is the selectivity test of the sensor towards AA. Several substances were chosen as interferants based on their common presence together with AA in human body fluids, namely uric acid (UA)43,44, dopamine (DA)45,46,47, glucose (GL)48,49,50, and urea (UR)51,52. The AA concentration used was 1800 µM, while UA was 200 µM, UR was 7000 µM, GL was 200 µM, and DA was 10 µM. All substances were dissolved in 50 mM PB pH 5. The selectivity test was carried out using DPV with the exact same parameters as the sensitivity measurement of AA. The detection tests were conducted in several configurations: in a state with no substance at all (only 50 mM PB pH 5) as the baseline, individually for each substance, in a pair configuration (AA-DA, AA-UA, AA-UR, and AA-GL), and in a simultaneous scheme (all substances mixed into one solution). The experimental configuration of this stage is the same as in Fig. 1c.

Results and discussion

Proposed mechanism of the gold nanodendrites electrodeposition synthesis

Before discussing the experimental results, the mechanism of gold nanodendrite synthesis in this study will be briefly explained. Figure 2 shows an explanatory illustration of the cysteine mechanism in directing the growth of gold nanodendrites structures. Constant potential amperometry is applied to the screen-printed carbon electrodes (three-electrodes system) in a deposition precursor solution containing HAuCl4 (aq) + H2SO4 (aq) + L-cys (aq). Initially, the electrodeposition process starts as several Au0 molecules begin to grow on the carbon working electrode (WE) surface. At the same time, cysteine molecules form thiol bonds with the deposited gold molecules. However, since a specific deposition potential is used, the L-Cys molecules detach from the Au(111) crystal planes while still remaining in other planes. This leads to the anisotropic growth of the Au molecules only in Au(111) direction. As time goes by, more Au molecules are deposited, forming dendritic branching structures called as gold nanodendrites (AuNDs).

Electrodeposited gold nanodendrite synthesis results

Before elaborating on the results of the electrodeposition optimization process, the results of the initial trial experiments will be explained. As mentioned in sub-chapter 2.3.1, the electrodeposition process in the initial trial experiment was conducted using constant potential amperometry (CPA) method with a deposition potential of − 0.8 V vs Ag/AgCl and a deposition time of 1500 s in a 550 µL deposition solution consisting of 1 mM HAuCl4 + 0.1 mM L-cys + 0.5 M H2SO4 based on the study by Ren et al.7. These are referred to as the first version of the initial electrodeposition parameters. During the process, HAuCl4 provides Au3+ ions which are reduced via electrodeposition to Au0 according to Eq. (1) 28. Meanwhile, H2SO4 acts as a supporting electrolyte, often used in the electrodeposition process to increase the conductivity of solutions, as well as maintain ionic conditions and the pH of the solution53. Finally, L-cys or L-cysteine acts as a growth-directing agent for gold nanoparticles, allowing the synthesis of nanodendrite morphology6,7.

Figure 3 shows the cyclic voltammograms in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution of the bare SPCE compared with the AuND-modified SPCE (SPCE-AuND) from the initial electrodeposition trial experiment. Based on the graph, it can be determined that gold particles have been successfully deposited on the carbon WE surface of the SPCE-AuND, as there are peaks or regions present on the voltammogram of SPCE-AuND which are specific to electrochemical reactions of gold-based electrodes. These peaks or regions always appear when CV is conducted using noble metal-based electrodes, such as gold, in an electrolyte solution like H2SO454,55. The figure also shows the voltammogram of the bare SPCE (inset shows the adjusted scale of the graph). No specific peaks or regions are observed since the WE surface consists only of activated carbon.

The designation of the peaks or regions in Fig. 3 is based on the reference voltammograms from the studies by Xiao et al.56 and Steel et al.55, while the explanation is mainly based on the study by Lukazewski et al.54. There are four peaks or regions on the SPCE-AuND voltammogram in Fig. 3: the double layer region, surface oxidation, oxygen evolution, and surface oxide reduction. The double layer region is an area in the voltammogram that is free from faradaic processes (reduction–oxidation at the electrodes), the value of the capacitive current in this area can be used to calculate the electrochemical surface area (ECSA)54,56. In the actual condition of the electrode, a double layer region is formed when two conducting phases meet at an interface, with one of the phases experiencing an excess of positive charge on its surface, while the other phase balances the charge with an equal magnitude but opposite sign57. Next is the surface oxidation peak/region, where an oxide surface is formed on the electrode (therefore also called as surface oxide formation). In other words, oxygen is adsorbed on the surface of the electrode54. Meanwhile, in the oxygen evolution region, an electrolysis reaction begins to occur, and thus forming molecular oxygen58. The last is the peak of surface oxide reduction, where oxygen undergoes desorption54.

In this study, the surface oxide reduction (SOR) peak/region is the main focus of analysis for it is often used to determine the real surface area (RSA) or electrochemical surface area (ECSA) of the electrode7,13,16. ECSA in cm2 is calculated using the Eq. (2) 28. Qtheoretical is the theoretical value (constant) of Au charge density which is 390 µC cm−2. While the Qactual is the charge value of Au based on the SOR reaction (in µC) which is obtained from Eq. (3) 28.

The integral result of the curve under the SOR region (in V A or W) is obtained using the peak integration feature in OriginPro software. The scan rate value used is 0.05 V s−1 , as employed during the CV characterization process. The roughness factor value (ρ), which is the ratio between the active or actual surface area and the geometric area of the electrode54,59, can be obtained from the calculated ECSA by dividing the ECSA value by the geometric area of the electrode (Ageometric) in cm2 according to Eq. (4) 28.

To determine the initial benchmark values for the optimization, the CV graph of the SPCE-AuND from the initial trial experiment in Fig. 3 was analyzed. The obtained values of the initial SOR peak current and the ECSA are − 56.08 µA and 24.73 mm2, respectively. As briefly mentioned in sub-chapter 2.3.1, an initial optimization experiment was also carried out during the initial trial experiment. The results can be seen in Fig. S1 (supplementary information). Firstly, the HAuCl4 concentration in the deposition solution was increased from 1 to 5 mM, becoming the second version of the initial electrodeposition parameters. The CPA graph of the deposition changed from Fig. S1a (i) to S1a (ii). An increase in current value was observed, but the curve became very unstable as seen in Fig. S1a (ii). Observation of the SPCE surface during the electrodeposition process also showed many bubbles emerging, as seen in Fig. S1c. The emergence of bubbles during the electrodeposition process could cause problems for the deposition result due to uneven structures of the metal layer deposited60. When the deposition was completed, black dirts formed on the electrode, which might indicate that parts of the electrode were dislodged due to the bubbles. The H2SO4 characteristic CV of the corresponding SPCE-AuND depicted in Fig. S1b (ii) also shows a very high current response with no specific peaks visible. There were also a lot of bubbles coming out of the electrode during this CV.

Due to these problems, the deposition parameters were adjusted. The H2SO4 concentration, which contributes ions to the deposition process, was reduced from 0.5 M to 0.1 M. Additionally, the deposition time parameter was reduced from 1500 to 1000 s to avoid further damage to the electrodes due to prolonged exposure. The new parameters are CPA with a deposition potential of − 0.8 V vs Ag/AgCl and a deposition time of 1000 s in 550 µL of seed solution consisting of 1 mM HAuCl4 + 0.1 mM L-cys + 0.1 M H2SO4. These are called the third version of initial electrodeposition parameters. As a result, the CPA graph of the process using the third version parameters is much more stable and smoother (Fig. S1a (iii)) compared to Fig. S1a (ii). It is even smoother than the CPA graph using the first version parameters depicted in Fig. S1a (i). The wave-like shape at the beginning of the graph in Fig. S1a (i) may also indicate instability in electrodeposition using the first version parameters, although the CV result is still relatively good (Fig. S1b (i)). Figure S1b (iii) shows the CV characterization graph of the SPCE-AuND fabricated using the third version parameters, similar to the result of the one fabricated using the first version parameters depicted in Fig. S1b (i). Based on the analysis of the CV graph (Fig. S1b (iii)), the SOR peak current and ECSA of the third version parameters are − 42.39 µA and 17.4 mm2, respectively. The electrodeposition parameters of the third version were then used as the initial parameters for the optimization process.

From the initial trial experiment result, it can be concluded that the electrodeposition parameters provided by Ren et al.7 cannot be directly applied in this study but requires adjustments. The main factor behind this need for adjustment is the difference in the type of electrode used. In the studies by Ren et al.7 and Lin et al.6 (which referenced Ren et al.61), a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) was used instead of SPCE. These two types of electrodes have significantly different properties or characteristics, especially regarding the fabrication process and geometric surface area. GCE is known for its extreme resistance to chemical attack (difficult to oxidize in oxygen, water and CO2) and its low electrical resistivity. This is because GCE is fabricated using a thermal degradation method based on polymeric carbon, making it resistant to high temperatures. Meanwhile, SPCE is fabricated by printing ink (carbon graphite) onto the substrate and then drying it62. This makes GCE more robust than SPCE in terms of the electrodeposition process. Additionally, the GCE (as a WE) used by Ren et al.7 has a geometric area size of 0.2376 cm2, while the SPCE used in this study has a smaller WE size of around 0.0415 cm2. This difference makes the resistivity of GCE smaller, allowing it to accommodate larger currents compared to SPCE.

The optimization of electrodeposition potential

The deposition potential is a crucial parameter in the electrodeposition process. Deposition potential is one of the factors that determines the morphology of the synthesized gold nanostructures13. The variation of deposition potentials used for the optimization process in this study was determined based on several references. One of the main references is the study by Lin et al.6, which concluded that to reduce Au3+ to Au0 in a deposition solution consisting of HAuCl4 and H2SO4 (allowing Au nanoparticles to be deposited on the SPCE surface), a deposition potential of less than + 0.8 V is needed. Additionally, the use of L-cys as an organic growth-directing agent to form dendritic structures also influenced the selection of deposition potential. Cysteine has a –SH (thiol) functional group that interacts with Au particles to form an Au–S covalent bond6. It binds with Au particles in certain crystal planes, namely (100), (110), and (111). However, it can also be released (undergoes desorption) from certain Au crystal planes via an electrochemical reaction depending on the applied potential. Based on the cysteine desorption test in KOH solution from the study by Lin et al.7, these specific potentials are − 0.76 V for (111), − 1.05 V for (100), and − 1.15 V for (110). Therefore, Lin et al. stated that the electrodeposition process at a potential of − 0.8 V is expected to release L-cys from the (111) plane while still maintaining attachment to the (100) and (110) planes. Thus, the anisotropic growth of Au during electrodeposition is directed only at the (111) plane, as the other planes are blocked by L-cys, resulting in dendritic structures of AuNPs. Ren et al. (2017) used Lin et al.’s study as a reference, which might explain why they also choose a deposition potential of − 0.8 V in their research to grow AuNDs.

Based on the reference, a deposition potential of − 0.8 V vs Ag/AgCl is likely the most optimal potential value for growing AuNDs. However, due to the appearance of bubbles during the initial electrodeposition process using this potential value, further optimization was necessary. The main goal was to identify a potential value that allows AuNDs growth without producing bubbles. According to several other reference studies, it is possible to synthesize gold nanodendrite structures using a deposition potential higher (“more positive”) than − 0.8 V vs Ag/AgCl. Shu et al.13 found that AuNDs could be grown using a deposition potential of − 0.3 V vs Ag/AgCl. In their study, using a more negative deposition potential (e.g. − 0.5 V and − 0.7 V) resulted in the emergence of air bubbles, hindering the growth of the nanodendrite structures. Another study by Sakai et al.63 used deposition potentials of 0 and + 0.3 V Ag/AgCl in NaAuCl4 + H2SO4 + L-cys solution and successfully produced dendritic and bumpy AuNP structures on tin oxide electrodes. Sakai et al. also conducted an experiment to find the desorption potential values of L-cys from Au crystal planes using KOH, with results similar to Lin et al.6, which were − 0.702 V for (111), − 0.987 V for (100), and − 1.023 V for (110). Sakai et al. (2009) explained that at a potential of 0 and + 0.3 V Ag/AgCl V, L-cys had detached from the (111) plane but were still attached to other crystal planes, allowing bumpy structures to be synthesized. At potential values of − 0.5 and − 0.3 V vs Ag/AgCl, smooth AuNP structures were produced, likely due to the random growth of Au particles after L-cys had been released from all crystal planes. The desorption potential values obtained by Sakai et al. (2009) and Lin et al. (2011) do not specify the exact potential of L-cys desorption but rather indicate the order of crystal plane desorption as the potential becomes more negative. These studies used KOH solution to find the desorption values, not H2SO4, the supporting electrolyte used in electrodeposition6,63. Thus, the desorption values should not be directly applied to the electrodeposition conditions using H2SO4. Sakai et al. (2009) validated the role of L-cys as a growth-directing agent, finding that at deposition potentials of − 0.5 and 0 V vs Ag/AgCl, smooth gold nanosphere structures were deposited sparsely when L-cys was not used, confirming its role as a growth-directing agent.

Based on these preliminary literature studies, the deposition potential values in the optimization experiment was determined to be + 0.8, + 0.5, + 0.2, − 0.1, − 0.4, − 0.5, − 0.6, − 0.7, − 0.8, and − 1 V vs Ag/AgCl. The other electrodeposition parameters used were in accordance with those used in the most recent initial trial experiment (the third initial electrodeposition parameters), which were CPA in 550 μL deposition solution consisting of 1 mM HAuCl4 + 0.1 mM L-cys + 0.1 M H2SO4 for 1000 s.

Figure 4a shows the full characteristic CVs in 0.5 M H2SO4 of SPCE-AuND synthesized using different variations of deposition potentials (the data shown are the second cycle of the CV process from one of the repetitions). Figure 4b shows the SOR region of the CVs. The relation between the deposition potential variation and the average peak current values of SOR area (from two repetitions) is plotted in Fig. 4c. The relation between the potentials and the average ECSA values (from two repetitions) is plotted in the Fig. 4d. It can be observed that, generally, the more negative the deposition potential, the higher the SOR peak current and the ECSA value. This agrees with Antuña-Jiménez et al.64, which stated that the more negative the deposition potential, the faster the nucleation rate, resulting in the growth of more small-sized nanoparticles and a wider ECSA of the electrode.

The data from the deposition potential parameter optimization of SPCE-AuND synthesis. (a) Comparison of the full cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of SPCE-AuNDs’ in 0.5 M H2SO4. (b) Comparison of the surface oxide reduction (SOR) region in the characteristic CVs SPCE-AuNDs’ in 0.5 M H2SO4. (c) The calibration plot of the deposition potential used during SPCE-AuND synthesis vs the peak current in the SOR region of the characteristic CV in 0.5 M H2SO4. (d) The calibration plot of the deposition potential used during SPCE-AuND synthesis vs the electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) of SPCE-AuND, calculated from the SOR region of the characteristic CV in 0.5 M H2SO4.

The data from − 1 V vs Ag/AgCl test is not included in Fig. 4 due to the inability to analyze the CV data, as it does not show a characteristic H2SO4 CV curve of gold-based electrodes and is rather noisy. This might be due to the electrode damage resulting from intense bubble formation during deposition at − 1 V vs Ag/AgCl. Figure 4c shows that the deposition potential of − 0.8 V vs Ag/AgCl produces the highest SOR peak current. Figure 4d shows that the potential of − 0.7 V vs Ag/AgCl produces the largest ECSA value. However, the error bar for the − 0.8 V vs Ag/AgCl data is much longer than for the other variations, indicating inconsistent test results. These two potential variations are shown in red to indicate that bubbles still formed during electrodeposition using these potentials, although not as much as when a potential of − 1 V vs Ag/AgCl was used. Therefore, a potential value of − 0.6 V vs Ag/AgCl was chosen as the optimal electrodeposition potential. Bubbles did not emerge during electrodeposition at − 0.6 V vs Ag/AgCl. It also has the third best performance based on both SOR peak current and ECSA values. This optimal value was then used in the next parameter optimization process (precursor concentration solution).

The optimization of electrodeposition precursor solution concentration

The next parameter to be optimized is the concentration of the deposition seed solution, particularly the concentration of HAuCl4, which contributes Au3+ ions. A study on dendrite-like gold nanostructures synthesis on glassy carbon electrode surface by Shu et al.13 describes an optimization of HAuCl4 concentration. The study conducted the synthesis using an electrodeposition technique in a solution containing HAuCl4 and KCl. SEM characterization shows that the number of the growing nanodendrite structures increases as the concentration of HAuCl4 increases, which is directly proportional to the increase in the peak currents of SOR in the H2SO4 CV characteristics and the ECSA13. However, there is a saturation point for this increase. Shu et al. (2014) varied the HAuCl4 concentration from 5 mM, 10 mM, to 20 mM. A significant increase in performance occurred when the HAuCl4 concentration increased from 5 to 10 mM. However, from 10 to 20 mM, there was no significant increase in performance based on the peak current of SOR and the ECSA, although SEM results showed that the nanodendrite structures grew more prominently at a concentration of 20 mM. Additionally, the gold nanodendrite structures deposited using the 20 mM concentration tended to be easier to remove from the surface of the carbon electrode. Based on that study, variations in optimization of HAuCl4 concentrations in this study were selected from 1 mM, 2 mM, 5 mM, and only up to 10 mM. Optimization of the HAuCl4 concentration was then carried out using these variations with the other deposition parameters used according to the results of the deposition potential optimization process.

Figure 5a shows the full characteristic CVs in 0.5 M H2SO4 of SPCE-AuND synthesized using different HAuCl4 concentration in the deposition seed solution (the data shown are the second cycle of the CV process from one of the repetitions). Figure 5b shows the SOR region of the CVs. Meanwhile, the relationship between the HAuCl4 concentration and the average peak current values of the SOR area (from two repetitions) is plotted in Fig. 5c. The relationship between HAuCl4 concentrations and the average ECSA values (from two repetitions) is plotted in Fig. 5d. A significant increase (i.e., about three folds) can be observed in the peak current and ECSA when the HAuCl4 concentration is increased from 1 to 10 mM. The standard deviation for each concentration variation is low. This is in accordance with the results from the study by Shu et al.13. The 10 mM concentration of HAuCl4 might also be close to the saturation point of this optimization. This is suggested by the fact that the increase in concentration from 5 to 10 mM did not significantly impact the resulting peak current absolute value of SOR (only around 17 µA) and the ECSA value (only around 7 mm2), compared to the impact of the concentration increase from 2 to 5 mM, which resulted in an increase in the SOR peak current by about 64 µA and an increase in ECSA by about 21 mm2. From these results, it was concluded that the optimal concentration of HAuCl4 in the deposition seed solution was 10 mM.

The data from the HAuCl4 concentration parameter optimization of SPCE-AuND synthesis. (a) Comparison of SPCE-AuNDs’ full characteristic cyclic voltammograms (CVs) in 0.5 M H2SO4. (b) Comparison of the surface oxide reduction (SOR) region of SPCE-AuNDs’ characteristic CVs in 0.5 M H2SO4. (c) The calibration plot of the HAuCl4 concentration used in the precursor solution during SPCE-AuND synthesis vs the peak current of the SPCE-AuND’s SOR region of the characteristic CV in 0.5 M H2SO4. (d) The calibration plot of the HAuCl4 concentration used in the precursor solution during SPCE-AuND synthesis vs the electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) of SPCE-AuND calculated from the SOR region of the characteristic CV in 0.5 M H2SO4.

The optimization of electrodeposition time

The final parameter to be optimized is the electrodeposition time. This parameter plays an important role in the gold nanodendrites electrodeposition process because longer deposition time generally results in denser gold nanodendrite structures13. This increase in density enhances the performance of the electrode by generating more active sites. Studies by Ren et al. (2017) and Shu et al. (2014) have optimized deposition time parameters for AuND electrodeposition7,13. Ren et al. (2017) varied the deposition time from 1000 s, 2000 s, to 3000 s; while Shu et al. varied the deposition time from 600 s, 1000 s, 2400 s, 3600 s, 5400 s, to 7200 s. In this study, the deposition time was varied from 500 s, 1000 s, 1500 s, up to 2000 s. The deposition time was not extended beyond 2000 s due to concerns that the SPCE used in this study might not be rigid enough to perform electrodeposition for longer times, unlike the GCE used in the study by Ren et al. (2017) and Shu et al. (2014).

As mentioned in sub-chapter 2.3.1, during the deposition time optimization process, the volume of the microtube used to contain the deposition solution was increased from 550 µL to 1500 µL. This adjustment was made because a larger volume of seed solution provides more precursor molecules of Au3+, thus preventing the depletion of these molecules during a longer deposition process. When a 1500 µL solution was used, a twofold increase in the constant potential amperometry current response with a more stable current value (no decrease of current response) was observed compared to using 550 µL of solution. In addition to adjusting the volume of the seed solution, the potential range of the CV electrochemical characterization process using 0.5 M H2SO4 was also adjusted. This adjustment was necessary due to a shift in the SOR peak current region of the SPCE-AuND voltammograms deposited for 1500 s and 2000 s, causing the peak to be unobservable. This shift likely occurred due to a change in the morphology of SPCE-AuND deposited for more than 1000 s, possibly due to the appearance of more complex gold nanodendrite structures, thus changing the complexity of the electrochemical reaction. This assumption is based on the results of CV characterization using several gold nanoparticle-modified electrodes with different morphologies, which have different specific CV peak potentials for H2SO4 solution as reported by M. Li et al.65. The other parameters used, such as deposition potential and precursor solution concentration, followed the results of the two previous optimization processes (− 0.6 V vs Ag/AgCl and solution of 10 mM HAuCl4 + 0.1 mM L-cys + 0.1 M H2SO4).

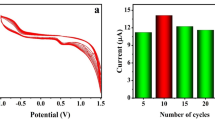

After shifting the potential range of CV characterization from 0.4–1.5 V to 0–1.2 V, the SOR peaks could be observed and analyzed, as can be seen in Fig. 6a (full characteristic CVs) and 6b (the SOR region of the CVs only). The data shown are from the second cycle of the CV process from one of the repetitions. It can be seen that there is a pattern of the SOR peak shifting toward the negative values as the deposition time increases. The relationship between the variation of deposition time and the average peak current values of SOR area (from two repetitions) is plotted in Fig. 6c. The relationship between deposition time and the average ECSA values (from two repetitions) is plotted in Fig. 6d. Initially, both the SOR peak current and ECSA values increase with longer deposition times, consistent with the results from studies by Ren et al. (2017) and Shu et al.7,13. However, this increasing pattern is not observed for ECSA data at deposition time of 1500 s and 2000 s. If the SOR peak current is used as the indicator, the 2000 s variation yields the best performance, whereas the 1500 s variation shows the best performance if the ECSA indicator is used. To solve this inconsistency, five additional cycles of CV characterization tests were carried out for these two deposition time variations with three repetitions each. This retest used 1500 µL of 0.5 M H2SO4 solution (instead of 100 µL droplet as in previous tests) to ensure an adequate amount of H2SO4 during the characterization, so any significant decrease in peak current could be attributed to the performance of the SPCE-AuND rather than the diminishing H2SO4 concentration during the test. In this retest, the indicators for determining the optimal variation were the SOR peak currents and the stability of the CV results for each cycle, including the absence of noise and the quality of the CV curve shape compared to previous tests.

The data from the deposition time parameter optimization of SPCE-AuND synthesis. (a) Comparison of SPCE-AuNDs’ full characteristic cyclic voltammograms (CVs) in 0.5 M H2SO4. (b) Comparison of the surface oxide reduction (SOR) region of SPCE-AuNDs’ characteristic CVs in 0.5 M H2SO4. (c) The calibration plot of the deposition time used during SPCE-AuND synthesis vs the peak current of the SPCE-AuND’s SOR region of the characteristic CV in 0.5 M H2SO4. (d) The calibration plot of the deposition time used during SPCE-AuND synthesis vs the electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) of SPCE-AuND calculated from the SOR region of the characteristic CV in 0.5 M H2SO4.

The results of this retest are shown in Table S1 in supplementary information, and the CV curves (5th cycle) can be seen in Fig. S2 in supplementary information. In general, the electrodes deposited for 1500 s produced higher SOR peak current than those deposited for 2000 s. Additionally, no defective electrodes were observed for 1500 s deposition time, whereas one electrode deposited for 2000 s was defective (repetition 2) and another had a noisy voltammogram (repetition 1). The lower SOR peak current yielded by the 2000 s variation could be due to the dislodgement of AuNDs from the electrode surface, as observed in the study by Shu et al.13. Additionally, excessive growth of AuND structures at the 2000 s deposition time might cause the structures at the bottom to be covered and unable to react well with the precursors, thereby reducing the ECSA of the electrode13. In this study, in agreement with the study by Shu et al. (2014), it was observed that the electrodes that are deposited with a longer deposition time (mostly the 2000 s deposition time) had the susceptibility for gold nanostructure dislodgment from the surface of the carbon electrode, marked by the appearance of scattered black dots (from the carbon surface) on the WE surface of the modified SPCE-AuND. Excessive growth of AuND structures was also observed at 2000 s deposition time, displayed by several brownish structures that grew beyond the WE area.

From this retest, it was determined that the most optimal deposition time parameter was 1500 s, resulting in complete optimal parameters for the SPCE-AuND electrodeposition process as constant potential amperometry (CPA) for 1500 s at a constant potential of − 0.6 V vs Ag/AgCl using 1500 μL of deposition precursor solution consisting of 10 mM HAuCl4 + 0.1 mM L-Cys + 0.1 M H2SO4.

The average SOR peak current value and ECSA value of the optimal SPCE-AuND were calculated to be − 311.77 µA and 134.81 mm2, respectively, based on the data shown in Fig. 6. The roughness factor (ρ) value of the optimal SPCE-AuND is 32.48 (Eq. (4)) and the WE geometric area of the SPCE is 0.0415 cm2. The ρ value is used to compare this study with other references since it is a dimensionless parameter. The obtained ρ value in this study is still lower than the ρ value of AuND obtained by Shu et al.13 which is about 64.29 (based on the calculations using the ECSA and the geometric area given in that study). This might be due to the longer deposition time (3600 s) used in Shu et al.’s study because a more robust electrode type was used (GCE), instead of the SPCE used in this study, resulting in more dendritic structures. Meanwhile, the ρ values from AuND studies by Ren et al. (2017) and Das et al. (2015) cannot be compared directly with this study, as the information supporting the calculation of the roughness factor was not provided in those studies7,16. Ren et al. (2017) provides the geometric area of the GCE electrode used but does not provide the ECSA value, while for the case of Das et al. (2015) is the opposite.

To assess the stability of the optimal SPCE-AuND electrochemical performance towards consecutive measurements (repeatability), repeated repetitions (25 cycles) of the CV process were carried out using 1500 μL solution of 0.5 M H2SO4 solution. The relative error average and the coefficient of variation of the surface oxide reduction peak current between the cycles were then calculated. The relative error was calculated using Eq. (5), while the coefficient of variation was calculated using Eq. (6). Errorrel is the relative error (in %), \({I}_{x}\) is the SOR peak current value of cycle \(x\) (in μA), \({I}_{ref}\) is the reference current value of the SOR peak taken from the first cycle of the test (in μA), CoV is the coefficient of variation, SD is the standard deviation of all the 25 cycles’ SOR peak current values (in μA), and Mean is the average of all the 25 cycles’ SOR peak current values (in μA).

The relative error average was then calculated by averaging all relative error values of the 25 cycles, resulting in 2.51%, as shown in the Table S2 in the supplementary information. In that table, the calculated SD and mean of all the 25 cycles’ SOR peak current values are shown which are 6.92 μA and \(-\) 319.84 μA, respectively. The CoV was calculated to be 2.16%. The relative error average and CoV values obtained from this test are quite low, indicating that the synthesized SPCE-AuND has stable electrochemical performance towards successive measurements. The CV curves of the repeating 25 cycles can be seen in Fig. S3 in the supplementary information.

The electrocatalytic performance of the optimal SPCE-AuND was also compared to bare SPCE by performing CV (50 mV s−1 scan rate) in 5 mM K3[Fe(CN)6] dissolved in 50 mM PB pH 5. It can be seen in Fig. S4 in the supplementary information that the anodic and cathodic peak currents of the optimal SPCE-AuND is 33.49 μA and 33.40 μA, respectively, with a peak-to-peak separation of 90.83 mV. In contrast, the bare SPCE has a peak anodic current of 21.73 μA and 22.38 μA, respectively, with a peak-to-peak separation of 236.12 mV. This indicates an increase in the anodic peak current of 11.76 μA or 54.11% and an increase in the cathodic peak current of 11.02 μA or 49.24% after the introduction of AuND on the bare WE surface of the SPCE. This improvement is due to the higher conductivity and larger surface area provided by the gold nanostructures. Moreover, the smaller peak-to-peak separation value of the optimal SPCE-AuND compared to the bare SPCE indicates a faster electron transfer rate in SPCE-AuND66.

Material characterization results

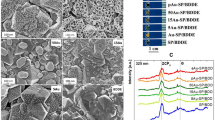

Three material characterization techniques were conducted in this study: field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) crystallography. These characterizations were used to confirm the formation of AuND and to analyze the characteristic properties of the SPCE-AuND. Material characterization was only carried out for deposition time optimization variations of the SPCE-AuND.

Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM)

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) characterization was carried out to confirm the formation and the morphology of the synthesized gold nanostructures. In general, based on the FESEM images depicted in Fig. 7, it can be confirmed that gold nanodendrite structures have been successfully grown on the carbon WE surface of the SPCE-AuND, especially for deposition time variation above 500 s.

FESEM images of gold nanoparticles electrodeposited on the surface of the SPCE’s working electrode (carbon) using constant potential amperometry (CPA) at − 0.6 V vs Ag/AgCl for (a) 500 s; (b) 1000 s; (c) 1500 s; and (d) 2000 s. Blue arrows indicate the “trunk” component, red arrows indicate the “branch” component, and the yellow arrows indicate the “leaf” component.

Figure 7a shows FESEM images of the WE surface for SPCE-AuND deposited for 500 s. Branching structures can be seen but it still looks sparsely grown. The formation of these branching structures might indicate that L-cys has successfully directed the branching growth of the gold nanoparticles during the electrodeposition process. Parts of the carbon surface that are only covered with gold nanoclusters at this deposition time can also be observed, similar to the condition of the electrode deposited for 2400 s in the study by Shu et al.13. Image with a scale of 0.5 µm in Fig. 7a shows the presence of "branches-leaves" components, typical of gold dendrites, as also shown in the study by Fang et al.67. In the image with a scale of 5 µm, lumpy gold structures can be seen, which were not completely covered by L-cys during the deposition process, causing them to grow in all directions.

Figure 7b shows the FESEM images of the successfully grown hierarchical dendritic structure of gold nanoparticles using a deposition time of 1000 s. The three components of gold dendritic structures, referred to by Fang et al.67 as “trunk”, “branch”, and “leaf” have been successfully grown. The “trunk” component has a length of 21 μm, the “branch” has a length of 5 μm, and the “leaf” has a length of 200 nm. Figure 7c and d show much more compact and branched structures of AuND. Figure 7c shows the FESEM image of the AuND structures grown using the electrochemically optimal deposition parameters (1500 s deposition time), while Fig. 7d is the one that used 2000 s deposition time. The blue arrows on the 1 µm scale images of both figures show the “trunk” component, the red arrows show the “branch” component, and the yellow arrows show the “leaf” component. Gold nanodendrite structures that appear in these two deposition variations have more “leaf” components compared to the previous variations. Even the “leaf” components seem to start to have more branches that look like serration structures. From Fig. 7c (top image), the size distribution of AuND was analyzed based on the length size of each gold nanodendrite branch. The mean value of the AuND branch size distribution is 1.59507 ± 0.05223 μm (Fig. S6). Figures 7c and 7d show that 2000 s deposition time yielded a slightly denser nanodendrite structures compared to 1500 s, supporting the electrochemical data shown in the Fig. 6. It also confirmed the hypothesis that 2000 s yielded excessive growth of gold nanoparticles, as seen in Fig. 7d that the dendritic structures grew over and piled up the other structures. In general, based on all the FESEM images, the “trunk” component of the AuNDs has a length of about 10 to 21 μm, followed by “branch” with a length of about 1 to 5 μm, and the “leaf” with a length of 200 to 500 nm.

Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS)

EDS was performed to characterize the optimal SPCE-AuND only (deposition time of 1500 s). This characterization process was chosen to understand the elemental composition of the WE at the optimal SPCE-AuND. The spectrum of the EDS can be seen in Fig. 8a, while the mapping of the EDS on the corresponding FESEM image can be seen in Fig. 8b. The mass percentage of gold (Au) based on the analysis dominates the modified WE surface of SPCE-AuND with a prominent percentage of 92.4%. The location of the Au peak from the spectrum is in good agreement with the studies by Lin et al. (2011) and Xu et al.6,15. Meanwhile, carbon (C) mass percentage detected is 6.7% that most likely came from the carbon surface of the WE on the SPCE which had not been fully covered by AuND. There are also sulfur molecules (S) detected with a relatively small mass percentage of 0.6%. There are two possible origins of element S, first from [SO4]2− which was adsorbed during the previously conducted electrochemical characterization process68, and the second from the thiol (–SH) group of L-cys attached on the surface of Au, although it is not supported by the fact that no nitrogen (N) molecule from L-cys was detected by EDS detector (mass percentage of N: 0%). Meanwhile, oxygen (O) was also detected with a mass percentage 0.3%. It probably came from the oxidized Au molecule which had not been reduced back during the CV characterization process in sulfuric acid solution or also from the adsorbed [SO4]2−.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) crystallography

X-ray diffraction (XRD) crystallographic characterization was performed to characterize only the optimal SPCE-AuND (deposition time of 1500 s). This characterization process was chosen to understand the crystal planes of the modified electrode surface. The process had to be carried out for all parts of the SPCE-AuND (including the WE, RE, CE, dielectric, and PET substrate) due to the XRD instrument’s holder limitation. The resulting spectrum results can be seen in Fig. 9. The naming of the XRD peaks is based on several study references, which will be explained sequentially in this section. Names of the peaks in blue writing indicate that the crystal plane peaks belong to the AuND structures, while other colors represent crystal planes from other structures/elements, such as polyethylene terephthalate or PET from the SPCE substrate (black), carbon from the base of WE (red), AgCl from RE and WE (green), and Ag from RE, CE, and the contact pad (violet).

There are five specific peaks of AuND identified from the XRD spectrum in Fig. 9, namely the peak of the crystal plane (111) at 38.2˚ which has the highest intensity, (200) at 44.4˚; (220) at 64.6˚; (311) at 77.6˚; and (222) at 81.8˚. The peaks of (111), (200), (220), and (311) are in accordance with several studies regarding the XRD spectra of gold nanodendrites, namely studies by Das et al. (2015), Lin et al. (2011), and Sorouri et al.1,6,16. The peak (222) is in accordance with the study by Lin et al.6. The higher intensity of the peak (111) relative to the other peaks of AuND crystal planes indicates that the use of L-Cys, plus the regulation of the deposition potential, succeeded in directing the growth of gold nanodendrite in the crystal plane (111) only, as it was mentioned by Lin et al.6.

Meanwhile, the other peaks of the XRD spectrum in Fig. 9 which are associated with peaks of the crystal planes other than AuND, are (110) at 23.2˚ and (100) at 26.0˚ from the PET substrate69; (002) in the range of 20–30˚ which is the peak of amorphous carbon from the WE base70 and (100) at 42.6˚ from graphite carbon of WE71; (200), (220), (222), (400), and (420) respectively at 32.2˚, 46.3˚, 57.6˚, 67.5˚, and 76.7˚72,73 and (422) at 85.7˚73, all from AgCl of CE and RE; and finally (142) at 54.83˚ and (210) at 27.81˚ from Ag of CE and RE74. There are still several other unidentified peaks that could come from the dielectric layer of the SPCE which are made of UV photoresist ink.

Analytes detection results

There are four stages of ascorbic acid (AA) analyte detection application: initial testing to find AA oxidation peak, AA diffusion-controlled reaction validation, the sensitivity test, and finally the selectivity test. The results of the experiments will be explained in this section.

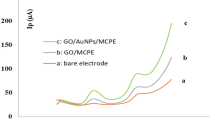

Initial testing of ascorbic acid oxidation reaction

Figure 10 shows the (a) cyclic voltammogram (CV) and (b) differential pulse voltammogram (DPV) of ascorbic acid oxidation peak initial detection testing at SPCE-AuND (using solution of 0 and 1800 μM AA dissolved in 50 mM PB pH 5). The DPV curves shown have been processed using the baseline subtraction feature in Origin Pro to facilitate peaks analysis. The oxidation (anodic) peak of ascorbic acid appeared at − 0.02 V vs Ag/AgCl in the cyclic voltammogram and at − 0.13 V vs Ag/AgCl in the differential pulse voltammogram (the blue color graph or 1800 μM AA graph). Both are within the potential range of the AA oxidation peak found in the study by H. Zhang et al.23 for the CV and Zheng et al.22 for the DPV. As seen in the figures, the use of PB pH 5 as the supporting electrolyte does not interfere with the AA oxidation peak. The PB pH 5 peak appears in the DPV curves (Fig. 10b) but it does not interfere with the AA peak. Even when the PB’s peak is shifted closer to the AA peak, as it is shown in the DPV curve of 0 μM AA, that PB’s peak still does not interfere with the AA peak shown in the overlaid 1800 μM AA’s DPV curve. It can also be seen that the use of DPV technique increases the peak current of AA oxidation by around six times compared to CV technique (from about 20 µA to about 125 µA for 1800 μM AA case). This is in agreement with the theory that the DPV technique is more sensitive (yielding a higher current value) compared to linear sweep method (such as CV) due to the minimization of capacitive current75. The CV technique was used in this section for initial exploratory purposes and will be further used in the AA diffusion-controlled reaction validation test. Meanwhile, the DPV technique was used since it will be further used in the sensitivity and selectivity tests of AA detection.

Ascorbic acid diffusion-controlled reaction validation

Diffusion-controlled mechanism of the redox species (i.e., analytes) is preferable to a surface-bound or adsorbed mechanism for electrochemical sensing. A sensing mechanism that involves the diffusion of a free redox species from the bulk of the solution towards the electrode surface (mass transport) takes advantage of the relationship between changes in the concentration of the analyte undergoing a redox reaction and changes in the current at the electrode due to the diffusion of the redox substance to and from the electrode. A concentration gradient is established towards the electrode surface as diffusion occurs. Surface-bound mechanisms do not generate concentration profile in the vicinity of the electrode surface; thus, this mechanism is unsuitable for amperometry-based detection. Ascertaining which mass transport mechanism (diffusion-control or surface-bound) is governing the underlying electrochemical reaction can be determined using the Randles–Ševčík equation. If a linear relationship between the peak current value (Ip) and the square root of scan rate (ν½) can be established, the underlying mass transport mechanism is diffusion-controlled rather than surface-bound. A faster scan rate indicates a faster reaction time. A shorter time frame to travel over the same distance during diffusion causes an increase in the velocity of the diffusion flux from the substance to the electrode, thus increasing the concentration gradient (higher current output or higher Ip). The Randles–Ševčík equation can be seen in the Eq. (7) where Ip is the CV peak current (in μA), n is the number of electrons transferred (in mol), A is the electrode surface area (in cm2), c is the concentration of the solution (in mol cm−3), ν is the scan rate of the CV (in V s−1), and D is the diffusion coefficient (in cm2 s−1). The 2.69 × 105 constant is in C mol−1 V½40.

The validation of diffusion-controlled reaction of SPCE-AuND towards AA was carried out by performing CV in 3600 µM AA (50 mM PB pH 5) at several scan rate variations. The results of these tests can be seen in Fig. 11, with the cyclic voltammograms of the scan-rate variation shown in Fig. 11a (the data shown are the second cycle of the CV process) and the calibration plot between the square root of the CV scan rates (ν½) and the resulting oxidation (anodic) peak current (Ip) values shown in Fig. 11b. Based on the data, it is evident that there is a linear relationship between the ν½ and the Ip with an R2 value of 0.9886, confirming that the reaction mechanism of the SPCE-AuND-based electrochemical sensor is diffusion-controlled40.

Sensitivity

The mechanism of the AA oxidation reaction in this electrochemical detection scheme involves the release of two electrons and two protons from ascorbic acid, which is irreversibly oxidized to dehydro-ascorbic acid30. This oxidation reaction is illustrated in Fig. 12 (redrawn from the study by Morelli et al.76). In an enzymatic electrochemical sensor, the ascorbate oxidase enzyme is utilized to catalyze this oxidation process77. In a non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor, like the one developed in this study, certain chemicals (such as nanomaterials or nanocomposites) can be used as catalysts for this oxidation reaction30,78. The performance of such sensors in detecting this reaction is widely referred to as sensitivity performance, which is tested by varying several known concentrations of the analyte (AA) and analyzing the corresponding current signal. This section explains the sensitivity test results.

Figure 13a shows the differential pulse voltammograms (baseline subtracted) of AA detection in 50 mM PB pH 5. The data shown are from one of the repetitions, while the calibration plot between AA concentration variations and the corresponding oxidation (anodic) peak current values can be seen in Fig. 13b (three repetitions). The potential range used for detection was narrowed to − 0.4 to 0.1 V vs Ag/AgCl compared to the initial DPV testing to focus on the AA range only. It can be observed in Fig. 13a that there is a shift in the peak of AA oxidation to the negative direction when the concentration of AA decreases. This shift is most likely due to the complexity of the reaction mechanism on the electrodes79. From the data, the standard deviation value of the current for the blanks (0 μM AA in PB pH 5) was 0.321 μA, while the slope value of the calibration plot, which is also the sensitivity of the sensor, was 0.0629 μA μM−1 (or 1.5157 μA μM−1 cm−2 if we divided it by working electrode’s geometric area of 0.0415 cm2). The full regression formula obtained from Fig. 13b is y = 0.0629x − 7.45, where y is the anodic peak current of AA in μA and x is the AA concentration in μM. These values were then used to calculate the detection performance of the sensor, namely the limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ). The limit of detection is the minimum amount of an analyte in a sample that can be detected regardless of bias or precision, while the limit of quantification is the minimum amount of analyte that can be measured (quantitated) precisely and accurately80. The formula for LOD is shown in the Eq. (8), while the LOQ formula is shown in Eq. (9), with σ being the standard deviation of the current of the blank response (in μA) and s is the slope (in μA μM−1) obtained from the linear regression of the calibration plot80.

Using Eqs. (8) and (9), as well as the value of σ (0.321 μA) and s (0.0629 μA μM−1) obtained from the analysis of the data shown in the Fig. 13, the LOD and LOQ values of AA detection using SPCE-AuND were calculated to be 16.8 μM and 51.0 μM, respectively. The calibration plot in Fig. 13b, shows that the linear range from AA detection in this study is 180–2700 μM with an R2 value of 0.9909. This detection linear range is within the normal AA concentration range in human body fluids, such as urine; which is around 0 to 2000 µM depending on consumption81,82; and tears; which is around 220–1310 µM (in basal tears)83 and 150–2570 µM (in reflex tears)84. Moreover, the LOD and LOQ values obtained are within (and even lower for LOD) the range of AA concentration in serum; which is 25–114 µM85; and plasma; which is 61.4–80 µM86 or 56–68 µM87. Therefore, these results show promising potential for this SPCE-based AA sensor to be implemented as a point-of-care detection device. A preliminary AA sensing test was also performed using commercial multivitamin supplements (CDR®, Bayer, Germany) containing calcium (250 mg), vitamin C (1000 mg), vitamin D (300 IU), and vitamin B6 (15 mg). Figure S7 shows the detection result of our sensor for several vitamin C (in CDR®) concentrations. The AA peak’s potential is in a similar range to the sensitivity test results shown in Fig. 13, which is around − 0.2 to 0 V depending on the concentrations. However, the AA peak current is lower than in the sensitivity test (Fig. 13), possibly due to the presence of other chemicals in the CDR® solution that attenuates AA signal.

When compared with several other studies that have successfully detected ascorbic acid, as shown in Table 1, it can be seen that the LOD values and linear ranges from this study are relatively comparable, especially when compared with the studies by Zheng et al. (2013) and H. Zhang et al. (2013) which both utilize similar morphology of AuNPs. The study by Zheng et al. yielded a LOD detection performance of 10 μM with a linear range from 60–500 μM, while the LOD from the study by H. Zhang et al. is 8.2 μM with a linear range of 10–12,000 μM22,23.

This comparability can be attributed to the properties of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), which are known for their significant role in enhancing the sensitivity of electrochemical sensors. Gold nanoparticles featuring a predominant (111) plane are particularly notable in electroanalytical chemistry because they can enhance sensitivity towards the electrochemical oxidation of various bioanalytes88. Gold nanodendrites feature a high active surface area, electrical conductivity, and catalytic properties1,2,89. Their nanodendritic structure offers an expanded surface area, providing more active sites for the adsorption and reaction of ascorbic acid, thus improving the sensor's sensitivity. The high electrical conductivity of gold nanodendrites ensures efficient electron transfer during the redox reactions of ascorbic acid, leading to an increased current response and enhanced sensitivity. The numerous active sites on the surface of gold nanodendrites boost the sensor's electrocatalytic activity for ascorbic acid's redox reactions, reducing interference from other electroactive species in the sample and thereby increasing specificity.

However, in this study, the detection limit (LOD) and quantification limit (LOQ) obtained are relatively high compared to other nanomaterial-based sensors. This may be due to the inconsistencies in the size and shape of the formed gold nanoparticles, leading to uneven distribution of active sites and less effective interaction between the target analyte and the gold nanoparticles, which affects the sensor's ability to accurately detect low concentrations. Gold nanoparticles have a strong affinity for various organic or biological molecules90. However, if the functional groups do not have a high affinity for the analyte, the sensor may not efficiently detect low concentrations, thereby increasing the LOD and LOQ values. It is also important to notice that the other references in Table 1 mostly use higher geometric surface area of working electrodes (such as glassy carbon electrode and gold electrode) with more sample volume, unlike this study which uses screen-printed electrodes and small volume (in the form of droplet). These factors could contribute to the relatively higher LOD and LOQ obtained in this study compared to them. However, in Table 1, unfortunately we could not show the references’ sensitivity performance using the value divided by each geometric surface area of the electrode used, as some of them did not mention their electrode’s geometric area. Regardless of this, since gold is relatively more biocompatible89 compared to other nanomaterial (especially the metal-based material), it is still promising for real-world biomedical application.

The durability performance of the sensor was also tested, with the corresponding data shown in Fig. S5 in the supplementary information. Until day 8, the sensor shows relatively constant performance in AA detection, even with the sensor being used three times (day 1, 4, and 8). The relative error (calculated using Eq. 5) of the current responses with the data of day 1 used as the reference is 2.07% for day 4 and 6.11% for day 8. This indicates that the sensor is durable and repeatable for AA detection for at least until day 8. However, the data from days 15 and 28 each show a decline in current response, with the current value relative to day 1 is about 66.28% on day 15 (after being used for the 4th time) and 72.84% in day 28 (after being used for the 5th time). However, even with this decline the sensor still could yield a relatively high current response of AA detection.

Selectivity