Abstract

Poststroke aphasia hinders patients’ emotional processing and social adaptation. This study estimated the risks of depression and related symptoms in patients developing or not developing aphasia after various types of stroke. Using data from the US Collaborative Network within the TriNetX Diamond Network, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of adults experiencing their first stroke between 2013 and 2022. Diagnoses were confirmed using corresponding International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes. Patients were stratified by poststroke aphasia status and stroke type, with propensity score matching performed to control for confounders. The primary outcome was depression within one year post-stroke; secondary outcomes included anxiety, fatigue, agitation, emotional impact, and insomnia. Each matched group comprised 12,333 patients. The risk of depression was significantly higher in patients with poststroke aphasia (hazard ratio: 1.728; 95% CI 1.464–2.038; p < 0.001), especially those with post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia (hazard ratio: 2.321; 95% CI 1.814–2.970; p < 0.001). Patients with poststroke aphasia also had higher risks of fatigue, agitation, and emotional impact. Anxiety and insomnia risks were higher in those with post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia. Poststroke aphasia, particularly post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia, may increase the risks of depression and associated symptoms, indicating the need for comprehensive psychiatric assessments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of long-term disability and mortality globally, and it has profound implications for affected individuals and their family members. Approximately 85% and 12% of all stroke cases involve ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, respectively1. Hemorrhagic stroke involves hematoma formation and inflammation, potentially raising intracranial pressure, while ischemic stroke features a necrotic core and an ischemic penumbra with preserved neuronal function due to collateral circulation2.

Among the various sequelae of stroke, poststroke depression, which typically occurs within the first year, is the most common and burdensome neuropsychiatric complication, affecting recovery, rehabilitation, and overall quality of life3. Relevant meta-analyses have reported that the cross-sectional prevalence of poststroke depression ranges from 18 to 33%4,5. Poststroke depression not only prolongs the process of recovery but also increases the risks of morbidity and mortality6. Although commonly linked to ischemic stroke, poststroke depression is also prevalent in hemorrhagic stroke, with a prospective cohort study showing that the risk of depression is more than twice as high in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage compared to those with ischemic stroke7.

Aphasia is a disorder that is characterized by an acquired loss or impairment of language after brain damage. Approximately one-third of all stroke survivors develop aphasia8, which complicates the recovery process. Individuals with aphasia are at high risks of complications and neurological disability, which lead to functional limitations and reduced quality of life compared with the outcomes in individuals without poststroke aphasia9. Notably, aphasia not only hampers communication but also hinders emotional processing and social adaptation10.

Small-scale studies have shown that depression is more prominent among patients with aphasia than those without aphasia, and that depressive symptoms do not appear to diminish over time for individuals with chronic aphasia11,12. Lin et al. recently conducted a population-based cohort study involving Taiwanese individuals, and they reported that the incidence of depression was higher in individuals with poststroke aphasia than in those without it, regardless of sex or stroke type13; in their study, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for the risk of depression was 1.21 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.15–1.29).

Anxiety is the feeling of fear that occurs when faced with threatening or stressful situations14. Comorbid depression and anxiety disorders are present in up to 25% of patients in general practice15. Insomnia, anxiety, and depression commonly co-occurred and were closely related16. A prospective cohort study reported anxiety and insomnia complicate poststroke recovery, especially in hemorrhagic stroke aphasia patients who face higher risks than those with ischemic stroke7. In addition, depression and anxiety can contribute to reduced appetite, which is a common issue in patients with aphasia17,18.

Fatigue, a prevalent symptom among stroke survivors, is particularly pronounced in patients with aphasia19,20. Fatigue is also a clinical symptom of depression21. Individuals with aphasia exhibiting higher levels of fatigue are inclined to report reduced social participation20. Agitation, characterized by irritability or severe restlessness, is a common physiological process related to depression and is also prevalent in poststroke aphasia patients22. Previous studies have shown that the risk of agitation is significantly higher in patients with aphasia23. Suicidal ideation, characterized by thoughts of self-harm, represents a serious mental health concern with potentially severe consequences if left untreated24. This depression-related issue is also common among patients with language impairment in clinical practice25.

The emotional impact of aphasia extends beyond symptoms related to depression and anxiety, encompassing a broad and profound range of effects. Aphasia can elicit both positive and negative emotions, such as agitation, apathy, irritability, and unhappiness. These emotional responses significantly influence an individual's psychological state and overall well-being, highlighting the complex interplay between aphasia and mental health26.

Evidence suggests an association between depression risk and poststroke aphasia. In their stroke genetics network study, Wassertheil-Smoller et al. demonstrated that the risk of poststroke depression is influenced by not only stroke types and genetic factors but also ethnicity27. Therefore, findings from studies associating depression risk with poststroke aphasia must be confirmed using larger databases. Furthermore, the associations of poststroke aphasia with the risks of anxiety and other depression-related symptoms, such as poor appetite, fatigue, agitation, insomnia, self-harm behavior, and emotional impact, remain unclear.

To bridge the aforementioned knowledge gap, the present study evaluated the risks of depression and associated symptoms in patients with poststroke aphasia and investigated the effects of different strokes, particularly ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes, on these risks.

Methods

Study design and ethics declarations

This retrospective, observational cohort study was conducted using data from the US Collaborative Network within the TriNetX Diamond Network, a comprehensive repository of electronic medical records, medical claims, and pharmacy claims. The data set included comprehensive information on patient demographics, diagnoses, medication records, laboratory test results, and health-care utilization, coded in accordance with standard systems. Notably, TriNetX curates longitudinal data every 3 months from 92 sites, representing more than 212 million patients.

The TriNetX platform adheres to the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the General Data Protection Regulation. The present study was conducted in accordance with relevant regulations and standards. Data de-identification is formally attested as per section §164.514(b)(1) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the anonymized nature of the data (the TriNetX platform stores deidentified data) and the retrospective nature of this study. Additionally, the use of TriNetX in the current study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital.

Study cohort

A flowchart of the patient selection process is presented in Fig. 1. This study included adult (aged ≥ 18 years) patients who had their first-ever stroke between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2022. The diagnoses of various strokes were confirmed using the following International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes: I63 (cerebral infarction), I60 (nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage), and I61 (nontraumatic intracerebral hemorrhage). The diagnoses of aphasia were confirmed using the following ICD-10-CM codes: R47.01 (aphasia), I69.920 (aphasia after unspecified cerebrovascular disease), and I69.320 (aphasia after cerebral infarction). Notably, in our cohort, aphasia was diagnosed within 3 months after the stroke event. The patients were stratified into two groups according to poststroke aphasia status: a case group (comprising patients with aphasia) and a control group (comprising those without aphasia). We excluded patients who were aged < 18 years; died before aphasia diagnosis; or had a history of depression (ICD-10-CM codes: F32 and F33), anxiety (ICD-10-CM codes: F40 and F41), schizophrenia (ICD-10-CM codes: F20–F29), bipolar disorder (ICD-10-CM code: F31), intellectual disabilities (ICD-10-CM codes: F70–F79), suicidal ideation and attempts (ICD-10-CM codes: R45.851 and T14.91, respectively), or prestroke aphasia.

The patients were divided into subgroups according to stroke type (ischemic stroke [ICD-10-CM code: I63 excluding I60 and I61] vs. hemorrhagic stroke [ICD-10-CM codes: I60 and I61]) for analysis.

Study outcomes

The primary study outcome was the development of depression within 1 year after stroke (during the follow-up period). The secondary study outcomes were the development of anxiety and other depression-related symptoms within 1 year after stroke. The other symptoms included poor appetite (ICD-10-CM code: R63.0), fatigue (ICD-10-CM codes: R53.81 and R53.83), insomnia (ICD-10-CM code: G47.0), self-harm ideation (ICD-10-CM codes: X71–X83, R45.851, T14.91, and R45.88), agitation (ICD-10-CM codes: R45.1 and R45.4), and emotional impact (ICD-10-CM code: R45).

Statistical analysis

To mitigate the effects of confounding factors, we performed propensity score matching (PSM) to establish groups with balanced baseline characteristics. Through greedy nearest neighbor matching, 1:1 PSM was performed using a built-in function within TriNetX. Specifically, the groups were matched by age, sex, race (White, African American, Hispanic or Latino, and Asian), marital status (never married), low income (ICD-10-CM code: Z59.6), hypertension (ICD-10-CM code: I10), atrial fibrillation (ICD-10-CM code: I48), heart failure (ICD-10-CM code: I50), chronic kidney disease (ICD-10-CM code: N18), diabetes mellitus (ICD-10-CM code: E08–E13), hyperlipidemia (ICD-10-CM code: E78.5), overweight and obesity (ICD-10-CM code: E66), epilepsy (ICD-10-CM code: G40), chronic pain (ICD-10-CM code: G89.2), dementia (ICD-10-CM code: F03), smoking (ICD-10-CM code: F17), alcohol use (ICD-10-CM code: F10), hypnotic use, antidepressant use, antipsychotic use, and anticonvulsant use before the index date (stroke diagnosis). Standardized differences were calculated to examine the balance of baseline characteristics between the propensity score–matched groups. A standardized difference of < 0.1 was considered to indicate a small between-group difference. HRs with 95% CI values were calculated for all outcomes. The TriNetX user interface was used for risk analysis and Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. In the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, between-group differences were determined using a log-rank test and a Cox proportional-hazards model.

Results

Patient groups

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study cohort. After the application of the exclusion criteria, the case and control groups comprised 12,337 and 937,883 patients, respectively. After PSM, each group comprised 12,333 patients. The median follow-up time is 365 days for both groups.

Patient characteristics at baseline and after PSM

Before PSM, the case group was older than the control group (65.8 ± 13.1 vs. 64.0 ± 14.3 years, respectively). The proportion of men was slightly higher in the case group than in the control group (55.6% vs. 54.7%, respectively; p = 0.093). White patients constituted the majority of both groups, followed by African American patients. The proportion of White patients was higher in the case group than in the control group (51.2% vs. 48.7%, respectively). After PSM, the two groups were well-matched regarding the distribution of demographic variables, comorbidities, and drug usage (standardized differences < 0.1).

Risks of depression and associated symptoms in the study cohort

Table 2 presents the risks of depression, anxiety, and other depression-related symptoms in patients with poststroke aphasia. During the 1-year follow-up period, the incidence rates for the case group and the control group are 44.4 and 28.3 per 1,000 person-years, respectively. The risk of depression was significantly higher in the case group than in the control group (HR: 1.728; 95% CI 1.464–2.038; p < 0.001). However, the risk of anxiety did not differ significantly between the two groups (HR: 1.160; 95% CI 0.969–1.390; p = 0.106). The risks of poor appetite, fatigue, agitation, and emotional impact were significantly higher in the case group than in the control group. However, no significant between-group difference was observed in insomnia or self-harm ideation.

Risks of depression and associated symptoms in patients stratified by stroke type

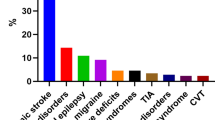

Figure 2 illustrates Kaplan–Meier curves depicting the risks of depression in patients with poststroke aphasia stratified by stroke type. Significant differences were noted in the risks of depression between patients with poststroke aphasia compared to those without aphasia across different stroke types (log-rank test, p < 0.001). Figure 3 revealed the Kaplan–Meier curves depicting depression in post-ischemic-stroke aphasia compared to post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia. Figure 4 showed risks of depression and associated symptoms in patients stratified by stroke type. There were 9,456 individuals in both the case and control groups for post-ischemic stroke and 3,158 individuals in both the case and control groups for post-hemorrhagic stroke. The risk of depression was higher in patients with post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia than in those with post-ischemic-stroke aphasia (HR: 2.321 [95% CI 1.814–2.970; p < 0.001] and 1.543 [95% CI 1.277–1.865; p < 0.001], respectively). In addition, the risks of fatigue, agitation, and emotional impact were significantly elevated in both groups. Although the risk of poor appetite was significantly higher in the overall case group compared to the control group, subgroup analyses of post-hemorrhagic stroke and post-ischemic stroke revealed no significant difference in poor appetite between both groups. Notably, the risk of anxiety was significantly higher in patients with post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia than in those without it (HR: 1.494; 95% CI 1.135–1.967; p = 0.004); however, no significant difference in anxiety risk was observed between patients with post-ischemic-stroke aphasia and those without it. Furthermore, the risk of insomnia was significantly higher in patients with post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia than in those without it (HR: 1.480; 95% CI 1.126–1.944; p = 0.005). Depression in post-stroke aphasia before and after PSM stratified by stroke type was presented in Table 3.

Discussion

We investigated the risks of depression and associated symptoms in patients with poststroke aphasia. The risk of depression was significantly higher in patients with poststroke aphasia than in those without it. Regarding depression-related symptoms, the risks of fatigue, agitation, and emotional impact were significantly elevated in patients with poststroke aphasia. Notably, patients with post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia were at increased risks of depression, anxiety, and insomnia.

In our study, the risk of depression during the 1-year follow-up period was significantly higher in patients with poststroke aphasia than in those without it. Emotional responses such as sadness and grief are common after poststroke aphasia and other impairments. These responses can hinder recovery, rehabilitation, and psychosocial adjustment28. Patients with poststroke aphasia typically encounter considerable functional limitations and experience reduced quality of life29. Furthermore, communication barriers stemming from poststroke aphasia may exacerbate patients’ emotional distress, compounded by a reluctance among stroke practitioners to offer interventions such as counseling30. The substantially elevated risk of depression in patients with poststroke aphasia highlights the need for addressing not only the physical but also the emotional and psychological consequences of stroke-related impairments.

Our study revealed considerable increases in the risks of fatigue, agitation, and emotional impact in patients with poststroke aphasia. Recent evidence suggests that patients with aphasia frequently experience an increased level of fatigue, which consequently reduces their levels of social engagement and participation20. Fatigue management is crucial for stroke survivors with aphasia; fatigue management strategies often involve medication, exercise, and psychological interventions31,32,33. Regarding agitation and emotional impact, the inability to control anger and aggressive behaviors is common in patients with aphasia34,35. Angelelli et al. indicated that the risk of agitation is fourfold higher in patients with aphasia than in those without it23. Another study evaluating anger in acute stroke survivors reported that 31% of all patients with poststroke aphasia exhibited irritability and aggression36. Because daily functional communication is impaired in these patients, they may become disheartened, less tolerant, and prone to becoming angry over trivial matters37. To avoid these problems, patients with poststroke aphasia must be evaluated for fatigue, agitation, and emotional impact and treated as necessary.

Our subgroup analysis revealed a strong association between depression risk and post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia. In their recent cohort study involving Taiwanese patients, Lin et al. demonstrated that the incidence of depression was higher in patients with poststroke aphasia than in those without it, regardless of sex or stroke type13. Our study, which was conducted using a relatively large database, revealed that the risk of depression was substantially elevated in patients with post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia. In a prospective cohort study, Zeng et al. reported that the odds ratio for poststroke depression was 2.65 (95% CI 1.34–5.24; p = 0.005) in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage when compared with those with ischemic stroke7. These findings are corroborated by results. Hemorrhagic strokes may induce biochemical changes in the brain, affecting areas involved in emotional processing, which, combined with a poor quality of life, can lead to depression7,38.

In our subgroup analysis, patients with post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia had significantly higher risks of anxiety and insomnia than did those without aphasia. However, no significant difference in the risk of anxiety or insomnia was noted between patients with post-ischemic-stroke aphasia and those without it. A prospective cohort study revealed that the risks of anxiety and insomnia were significantly higher in patients with hemorrhagic stroke than in those with ischemic stroke (61.8% vs. 44.7% [p = 0.006] and 50.1% vs. 31.8% [p = 0.003], respectively)7; these findings are consistent with ours. Another study indicated that anxiety persists throughout the poststroke recovery phase and may be more prevalent in patients with aphasia than in those without it39. Patients with poststroke aphasia develop linguistic anxiety, which is characterized by an abnormal stress response elicited by situations associated with poor language performance. However, the acute state of performance anxiety relative to the symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder remains to be comprehensively explored40. In our study, an end point was the development of anxiety within 1 year after stroke. In the future, the follow-up period should be extended to ≥ 5 years; this is because long-term observations may provide valuable insights into the trajectory and persistence of anxiety following stroke, particularly in patients with aphasia.

Notably, although we excluded patients with pre-existing diagnoses of depression and anxiety, some patients were still taking antidepressants. This may be due to antidepressants being prescribed for other indications, such as chronic pain conditions including back pain, knee osteoarthritis, postoperative pain, fibromyalgia, and neuropathic pain41. Additionally, patients may have experienced depressive or anxiety symptoms without a formal diagnosis. To address this potential confounder, we included antidepressant use in the PSM analysis.

This study has several limitations. First, aphasia can be classified as motor, sensory, or mixed aphasia; such variations make it challenging to perform subgroup analyses. Although we predicted that the risk of depression would be higher in patients with Broca’s aphasia than in those with Wernicke’s aphasia21,42, we could not investigate this notion because of data limitations. Second, although the severity of aphasia may be correlated with the risk of post-stroke depression43, our data does not include information on the severity of aphasia, making it difficult to analyze its relationship with the risk of depression. Third, depression is often diagnosed through language-based assessments, such as questionnaires and verbal interviews; such a diagnostic approach poses major challenges for patients with aphasia. Recent research has focused on developing non-language-based screening tools for depression but is limited by the noninclusion of patients with aphasia44. In the present study, although the conditions were diagnosed using ICD-10-CM codes, we could not ascertain whether depression was evaluated consistently and appropriately in our patients; therefore, the possibility of a bias cannot be eliminated. Future research should consider the development and utilization of more detailed and aphasia-sensitive instruments to better capture the symptomatology in this population. Fourth, stroke severity at baseline, low social support at three months, and loneliness and low satisfaction may be the predictors of psychological distress post stroke45. However, we could not adjust for factors not included in the patients’ electronic health records, such as their scores on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, Barthel Index, modified Rankin Scale, and degree of social support. Fifth, the depression-related symptoms included in this study are also crucial for diagnosing depression, as these symptoms may be integral to the depressive disorder itself. However, distinguishing between depression and depression-related symptoms using ICD-10-CM codes proves challenging. Additionally, it is difficult to determine whether certain symptoms are attributable to the effect of depression or stroke itself. For instance, post-stroke fatigue is an independent symptom and should be differentiated from fatigue associated with post-stroke depression46. Sixth, the prevalence of post-stroke aphasia in our sample, at 1.3%, is significantly lower than the generally reported prevalence of up to one-third. This discrepancy may be attributable to the fact that aphasia is a symptom that is challenging to obligatorily document using standard coding systems, potentially leading to an underestimation of its true prevalence. Seventh, the retrospective nature of this study made it susceptible to potential biases from unadjusted confounders. Finally, we excluded many underlying major psychological diseases, which limited our ability to explore certain aspects. Therefore, a cautious interpretation of the results and consideration of potential uncertainties are imperative for drawing accurate conclusions from our findings.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, our study has several strengths. Very few studies linking depression risk to poststroke aphasia have analyzed data from large databases. The present study was conducted using a large database. We found a substantially high risk of depression in patients with post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia. In addition to analyzing the risk of depression, we analyzed those of anxiety and other depression-related symptoms in patients with poststroke aphasia. Future studies may extend the observation period to ≥ 5 years, explore the associations between various mental illnesses and poststroke aphasia, and investigate the correlations between depression-related symptoms and poststroke aphasia.

Conclusion

The risk of depression may be considerably high in patients with poststroke aphasia, particularly those with post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia. Patients with aphasia are also at elevated risks of fatigue, agitation, and emotional impact. Furthermore, the risks of anxiety and insomnia are substantially higher in patients with post-hemorrhagic-stroke aphasia than in those without it. In summary, our findings suggest that poststroke aphasia increase the risks of depression and associated symptoms. Therefore, comprehensive psychiatric assessments are necessary for patients with poststroke aphasia.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mozaffarian, D. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2015 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation131, e29-322. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000152 (2015).

Zhou, H., Wei, Y. J. & Xie, G. Y. Research progress on post-stroke depression. Exp. Neurol.373, 114660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2023.114660 (2024).

Shi, Y., Yang, D., Zeng, Y. & Wu, W. Risk factors for post-stroke depression: A meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci.9, 218. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2017.00218 (2017).

Taylor-Rowan, M. et al. Prevalence of pre-stroke depression and its association with post-stroke depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med.49, 685–696. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291718002003 (2019).

Mitchell, A. J. et al. Prevalence and predictors of post-stroke mood disorders: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of depression, anxiety and adjustment disorder. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry47, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.04.001 (2017).

Hackett, M. L. & Pickles, K. Part I: Frequency of depression after stroke: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Stroke9, 1017–1025. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijs.12357 (2014).

Zeng, Y. Y. et al. Comparison of poststroke depression between acute ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke patients. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry36, 493–499. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5444 (2021).

Brady, M. C., Kelly, H., Godwin, J., Enderby, P. & Campbell, P. Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.2016, Cd000425. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4 (2016).

Lazar, R. M. & Boehme, A. K. Aphasia as a predictor of stroke outcome. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep.17, 83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0797-z (2017).

Thomas, S. A. & Lincoln, N. B. Predictors of emotional distress after stroke. Stroke39, 1240–1245. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.107.498279 (2008).

Shehata, G. A., El Mistikawi, T., Risha, A. S. & Hassan, H. S. The effect of aphasia upon personality traits, depression and anxiety among stroke patients. J. Affect. Disord.172, 312–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.027 (2015).

Pompon, R. H. et al. Associations among depression, demographic variables, and language impairments in chronic post-stroke aphasia. J. Commun. Disord.100, 106266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2022.106266 (2022).

Lin, H. L., Sung, F. C., Muo, C. H. & Chen, P. C. Depression risk in post-stroke aphasia patients: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology57, 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1159/000530070 (2023).

Dean, E. Anxiety. Nurs. Stand.30, 15. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.30.46.15.s17 (2016).

Tiller, J. W. Depression and anxiety. Med. J. Aust.199, S28-31. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja12.10628 (2013).

Mao, X. et al. The impact of insomnia on anxiety and depression: A longitudinal study of non-clinical young Chinese adult males. BMC Psychiatry23, 360. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04873-y (2023).

Engel, J. H. et al. Hardiness, depression, and emotional well-being and their association with appetite in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.59, 482–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03274.x (2011).

Edelkraut, L. et al. Spectrum of neuropsychiatric symptoms in chronic post-stroke aphasia. World J. Psychiatry12, 450–469. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v12.i3.450 (2022).

Alghamdi, I., Ariti, C., Williams, A., Wood, E. & Hewitt, J. Prevalence of fatigue after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Stroke J.6, 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969873211047681 (2021).

Quique, Y. M., Ashaie, S. A., Babbitt, E. M., Hurwitz, R. & Cherney, L. R. Fatigue influences social participation in aphasia: A cross-sectional and retrospective study using patient-reported measures. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.104, 1282–1288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2023.02.013 (2023).

Mohr, B., Stahl, B., Berthier, M. L. & Pulvermüller, F. Intensive communicative therapy reduces symptoms of depression in chronic nonfluent aphasia. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair.31, 1053–1062. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968317744275 (2017).

Siddiqui, W., Gupta, V. & Huecker, M. R. In StatPearls (StatPearls PublishingCopyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2024).

Angelelli, P. et al. Development of neuropsychiatric symptoms in poststroke patients: A cross-sectional study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand.110, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00297.x (2004).

Harmer, B., Lee, S., Rizvi, A. & Saadabadi, A. In StatPearls (StatPearls PublishingCopyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2024).

Costanza, A. et al. “Hard to say, hard to understand, hard to live”: possible associations between neurologic language impairments and suicide risk. Brain Sci.https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11121594 (2021).

Code, C., Hemsley, G. & Herrmann, M. The emotional impact of aphasia. Semin. Speech Lang.20, 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1064006 (1999).

Wassertheil-Smoller, S. et al. Polygenic risk for depression increases risk of ischemic stroke: From the stroke genetics network study. Stroke49, 543–548. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.117.018857 (2018).

Code, C. & Herrmann, M. The relevance of emotional and psychosocial factors in aphasia to rehabilitation. Neuropsychol. Rehabil.13, 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010244000291 (2003).

Hilari, K. The impact of stroke: Are people with aphasia different to those without?. Disabil. Rehabil.33, 211–218. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2010.508829 (2011).

Sekhon, J. K., Douglas, J. & Rose, M. L. Current Australian speech-language pathology practice in addressing psychological well-being in people with aphasia after stroke. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol.17, 252–262. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2015.1024170 (2015).

Kirkevold, M., Christensen, D., Andersen, G., Johansen, S. P. & Harder, I. Fatigue after stroke: Manifestations and strategies. Disabil. Rehabil.34, 665–670. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2011.615373 (2012).

Nadarajah, M. & Goh, H. T. Post-stroke fatigue: A review on prevalence, correlates, measurement, and management. Top. Stroke Rehabil.22, 208–220. https://doi.org/10.1179/1074935714z.0000000015 (2015).

De Groot, M. H., Phillips, S. J. & Eskes, G. A. Fatigue associated with stroke and other neurologic conditions: Implications for stroke rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.84, 1714–1720. https://doi.org/10.1053/s0003-9993(03)00346-0 (2003).

Osa García, A. et al. Predicting early post-stroke aphasia outcome from initial aphasia severity. Front. Neurol.11, 120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00120 (2020).

Ferro, J. M. & Santos, A. C. Emotions after stroke: A narrative update. Int. J. Stroke15, 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493019879662 (2020).

Santos, C. O., Caeiro, L., Ferro, J. M., Albuquerque, R. & Luísa Figueira, M. Anger, hostility and aggression in the first days of acute stroke. Eur. J. Neurol.13, 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01242.x (2006).

Benson, D. F. Psychiatric aspects of aphasia. Br. J. Psychiatry123, 555–566. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.123.5.555 (1973).

Wen, Q. H. et al. Relationship between depression after hemorrhagic stroke and auditory event-related potentials in a Chinese patient group. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat.18, 1917–1925. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.S362824 (2022).

Campbell Burton, C. A. et al. Frequency of anxiety after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Stroke8, 545–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00906.x (2013).

Cahana-Amitay, D. et al. Language as a stressor in aphasia. Aphasiology25, 593–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2010.541469 (2011).

Micó, J. A., Ardid, D., Berrocoso, E. & Eschalier, A. Antidepressants and pain. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.27, 348–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2006.05.004 (2006).

Starkstein, S. E. & Robinson, R. G. Aphasia and depression. Aphasiology2, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038808248883 (1988).

Zanella, C., Laures-Gore, J., Dotson, V. M. & Belagaje, S. R. Incidence of post-stroke depression symptoms and potential risk factors in adults with aphasia in a comprehensive stroke center. Top. Stroke Rehabil.30, 448–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2022.2070363 (2023).

Townend, E., Brady, M. & McLaughlan, K. A systematic evaluation of the adaptation of depression diagnostic methods for stroke survivors who have aphasia. Stroke38, 3076–3083. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.107.484238 (2007).

Hilari, K. et al. Psychological distress after stroke and aphasia: The first six months. Clin. Rehabil.24, 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215509346090 (2010).

Chen, W., Jiang, T., Huang, H. & Zeng, J. Post-stroke fatigue: A review of development, prevalence, predisposing factors, measurements, and treatments. Front. Neurol.14, 1298915. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1298915 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was edited by Wallace Academic Editing. This study was supported by the Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital (Grant Number: SKH-8302-103-DR-04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-K.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, and Visualization; C.-T.C.: Investigation, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, and Project administration. Both authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kao, SK., Chan, CT. Increased risk of depression and associated symptoms in poststroke aphasia. Sci Rep 14, 21352 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72742-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72742-z