Abstract

Health-related quality of life (HRQol) is a crucial dimension of care outcomes. Many HRQoL measures exist, but methodological and implementation challenges impede primary care (PC) use. We aim to develop and evaluate a novel machine learning (ML) algorithm that predicts binary risk levels among PC patients by combining validated elements from existing measures with demographic data from patient electronic health records (eHR) to increase predictive accuracy while reducing prospectively-collected data required to generate valid risk estimates. Self-report questions from previously validated QoL surveys were collected from PC patients and combined with their demographic and social determinant (SD) data to form a 53-question item bank from which ML chose the most predictive elements. For algorithm development, 375 observations were allocated to training (n = 301, 80%) or test partitions (n = 74, 20%). Questions that asked participants to rate how happy or satisfied they have been with their lives and how easy or hard their emotional health makes work/school showed a good ability to classify participants’ mental QoL (98% max balanced accuracy). Questions that asked participants to rate how easy or hard it is to do activities such as walking or climbing stairs and how much pain limits their everyday activities showed ability to classify physical QoL (94% max balanced accuracy). No demographic or SD factors were significantly predictive. Supervised machine learning can inform QoL measurements to reduce data collection, simplify scoring, and allow for meaningful use by clinicians. Results from the current study show that a reduced 4-question model may predict QoL almost as well as a full-length 40-question measure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a multi-dimensional assessment of how disease affects a patient’s health status and perceived well-being1. Commonly used self-report questionnaires can predict patient health outcomes. Evidence from the past two decades suggests that HRQoL is associated with overall morbidity and mortality1. Reduced HRQOL has shown a significant association with coronary heart disease and stroke2, cancer incidence3, long-term outcomes and all-cause mortality among cancer patients4,5, amputation, hospitalization, and mortality in individuals with diabetes6,7,8, disease-burden and survival among cystic fibrosis patients9, as well as mortality among community-dwelling populations and older adults10. HRQoL has also demonstrated significant associations with service utilization and healthcare costs11,12. Multiple QoL screening tools have been developed, though methodological and implementation barriers impede integration into community-based practice workflows.

The Quality of Life General 10-question Survey (QGEN10)13 and Quality of Life Disease Impact Scale (QDIS)14 surveys form a nationally validated quality of life measure. These measurements have demonstrated good psychometric properties and predictive value among chronically ill populations but are not commonly used in primary care (PC). Scoring formulas are not publicly available. Therefore, assessment requires prospective data collection and raw data transfer to the intellectual owner of the survey for scoring. Scored data is returned to the collection site as a series of 15 + norm-based and transformed variables representing aspects of patient mental and physical health. These profiles are not easily translatable as guides to clinical decision-making. Risk scores are returned as stand-alone spreadsheets and are not integrated into clinic systems, which impedes providers’ on-the-ground use. To facilitate meaningful use of QoL screening, clinicians require solutions that are easy to collect, interpret, and integrate into workflows.

There is movement towards integrating multiple data sources, such as eHR and social determinants of health, into QoL risk prediction15,16. Race, ethnicity, age, smoking status, BMI, household size, and income are significantly associated with HRQoL, though current screeners seldom leverage such demographic or other social determinant data17,18,19,20. Since practice sites routinely collect and house this information in their electronic health record (eHR), incorporating demographic factors into risk prediction algorithms may improve the accuracy of HRQoL risk estimates without additional prospective data collection.

Collaboration with PC providers to date has demonstrated a central need for a single risk score that is easy to access and interpret. Supervised machine learning may be a means to generate such a score. Preliminary evidence using machine learning (ML) has shown promise in predicting patients at risk for diminished QoL in some medical specialties21,22,23, but to our knowledge, ML methodologies have not yet been applied to PC populations. Leveraging this methodology to identify and combine the most predictive elements of previously validated measures can minimize patient burden by lowering the requisite number of patient-reported items needed to generate an accurate risk estimate. Simultaneously, one can incorporate potentially predictive patient factors extracted from the eHR to improve accuracy. By reducing the number of items and offering a set of straightforward, transparent decision support guidelines informed by ML, clinicians can build predictive data into routine clinical workflows at the point of service.

Objectives

-

1.

Develop and evaluate a novel ML algorithm to predict QoL risk level (high/low) among PC patients based on a unique set of demographic factors and previously validated patient self-report quality of life screening questions.

-

2.

Combine the most predictive elements of existing measures with demographic and SDOH data retrieved from patient eHR to generate a single, straightforward determination of mental or physical risk while reducing the required number of prospectively collected questions.

Methods

Overview and setting

Initial algorithms were developed using a convenience sample of PC patients from a single pilot site in Western Colorado. This medium-sized, community-based practice serves a diverse population of approximately 2500 pediatric and adult patients each year. Project work was deemed human subjects research exempt, and the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB) waived the need to obtain informed consent (protocol #20-2833). All methods were performed under the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Materials and data collection

QGEN10 and QDIS screeners result from 30 + years of development and refinement stemming from The Short Form 36 (SF36), created by RAND Corporation in 1992 as a 36-item survey to measure patient quality of life24. Over 3 decades, the SF36 was continuously validated and modified by the John Ware Research Group25 from its original format. Survey improvements have shortened the number of Likert-type questions required to generate an accurate risk estimate. Adding a chronic condition checklist has improved the validity of risk estimates26. A plethora of literature is available that details the development and evolution of SF36. For a comprehensive review, we recommend the 2000 article by John Ware titled SF-36 Health Survey Update25.

The SF-36 has become one of the most commonly used generic measures of health27,28. The resulting QGEN10 survey contains ten questions that measure eight health-related quality of life domains. Domain scores for physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, and general health are combined to produce a single composite score for physical health. Likewise, domain scores for vitality, social functioning, emotional role, and mental health are combined to produce a single mental health composite score. Composite scores are norm-based using population data collected over many years. QGEN10 composite-scored, patient-level risk estimates for physical and mental health were used as ground truth to train new ML algorithms in this study.

The Quality of Life Disease Impact Scale (QDIS) is a 15-question disease-specific survey in which patients identify their chronic conditions and rate each condition’s impact on their QoL. Recent evidence has suggested that a count of chronic conditions combined with their relative impact increases the survey’s ability to discriminate among clinically defined risk groups29. Patient responses are aggregated and weighted to generate a set of standardized scores that can be directly compared, though exact weighting calculations are not publicly available.

The QDIS allows investigators to choose target conditions for inclusion. However, based on previous John Ware Research Group studies, certain disease groups have shown more or less discriminatory capability26. For the current study, investigators chose to include 15 of the most common chronic conditions affecting US populations as published by the Center for Medicare Services (CMS)30, including Hypertension (HTN), coronary artery disease (CAD), congestive heart failure (CHF), myocardial infarction (MI), headaches (HO), cardiovascular accident (CVA), respiratory disease (RES), ulcerative colitis (UC), osteoarthritis upper extremity (OAU), osteoarthritis lower extremity (OAL), osteoarthritis other (OST), sciatica (SCA), diabetes mellitus (DM), major depressive disorder (MDD), and cancer (CA).

All questions from the QGEN10 and QDIS were loaded onto an electronic tablet and provided to patients upon check-in for their clinic visit between February 2021 and January 2023. See Table 1 for QGEN10 question and response options, which are made available with permission from the intellectual owner. For each chronic condition in our checklist, patients were asked to respond yes/no to the following question: “Have you ever been told by a health care professional that you have (X condition)?”. Respondents were asked to rank each condition’s impact on their quality of life over the last 4 weeks. Response options for the impact question ran on a Likert scale from “not at all” to “extremely” impactful. For most participants, the entire survey took less than 2 min to complete.

Participant responses for QGEN10 and QDIS questions were batch-routed to the survey scoring hub to calculate each patient’s mental and physical composite scores. Higher scores represent better quality of life, and lower scores represent poorer quality of life. Composite-scored data was returned to the project team and used as a known outcome to train novel machine learning algorithms.

The following demographic variables were retroactively extracted from the site eHR for each respondent: date of birth, race, ethnicity, sex, BMI, income, education level, housing status, insurance status, insurance name, evidence of tobacco use, # of distinct providers seen, # of office visits, and # of Emergency Department (ED) visits in the 12 months before QGEN/QDIS survey date. A random number generator created a unique patient identifier for each respondent to protect patient identity. All analyses for this study were conducted using R Studio version 4.1.231.

Exploratory data analysis

Descriptive statistics and estimates of missingness were generated for each demographic variable, plus the raw QGEN and QDIS questions. Due to the nature of eHR-based data entry, several demographic variables demonstrated numerous, small response categories, necessitating collapse into meaningful categories before modeling. Race and ethnicity variables were collapsed using federal classification standards published by the Department of the Interior32.

Classification algorithms

Norm-based mental and physical composite scores serving as the ground truth were collapsed into a binary (high/low) risk structure as follows: composite scores below the population mean minus 1 standard deviation were classified as high-risk, and the remainder of observations were classified as low-risk. This approach placed 15–20% of the sample into the high-risk group. At the advice of our clinical partners, this is a realistic percentage of the patient panel on which they could reasonably intervene. Separate models were trained to predict mental and physical risk.

Tree-based supervised machine learning techniques were used to develop prediction models by training on a dataset where the outcome is known and labeled with a pre-defined class. The model is then applied to unseen data where the outcome of unlabelled examples can be predicted based on the relationship between the data items determined in the training model33,34.

Multiple approaches were applied to the pilot data to develop and test risk classification algorithms. A review of the strengths and limitations of common supervised ML approaches was conducted and considered before finalizing the analysis plan. Based on the context and objectives of our research, our team decided that the key beneficial components of the following algorithms best suited our needs: Decision tree, support vector machine, random forest, boosting algorithms, and neural network. Ease of interpretation, small sample size, and low-dimensional data particularly informed our choice. Computation expense and speed were not deemed pressing issues for our small dataset. The exclusion of k-nearest neighbors technique was based on the limitation that it provides no information on which attributes are most effective at classification, which is critical for our objectives. See Table 2 for highlighted strengths and limitations of common supervised ML approaches33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40.

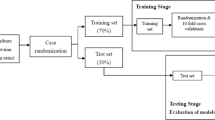

A single Classification and Regression Tree (CART) was fit to generate a decision diagram for mental and physical risk. Conducting this analysis first allows us to visualize a set of decision logics or ‘classification rules’33 used to systematically predict whether a patient is at high or low risk for decreased QoL based on the presence or absence of certain features. This simple but powerful cornerstone approach allows us to identify relevant characteristics and decision thresholds for predicting QoL. However, a single CART model may suffer from overfitting and/or instability35,36. To mitigate these issues, we then applied support vector machines, random forest, gradient boosting, and neural networks to our data to refine classification estimates while addressing model stability, overfitting, and bias. Performance metrics for each approach, along with relative influence for top predictors are presented. Variable importance measures can provide valuable insight into the magnitude of the effect of any single predictor41 on QoL risk level. We used the customary threshold or decision boundary 0.5 for all tree-based modeling to classify predicted probabilities. All algorithms used a 70/30 split to train and test classification. Estimates of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and balanced accuracy are presented to evaluate performance.

Results

Exploratory data analysis

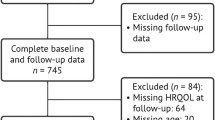

Univariate analysis

432 patients completed the QGEN and QDIS surveys. The practice site did not track the exact number of patients asked to complete the survey. However, it is estimated that 85–90% of patients who were asked chose to participate. 2 duplicate observations were removed, along with 3 observations from patients under 18 years of age, leaving 427 observations included for exploratory analysis. The scoring hub did not return composite scores for 52 observations. Data from these patients is included in the overall variable estimates but could not be stratified by risk level in the exploratory analysis.

Two SDoH variables displayed inconsistent presence in the eHR and were excluded from further analysis: patient housing status and patient income (both with greater than 70% missing across the entire sample). The following demographic variables were collapsed into more meaningful response categories before analysis: patient race, ethnicity, weight, tobacco use, and education. The patient’s date of birth and survey completion date were used to calculate the patient’s age at the time of the survey.

The majority of patients in our sample identified themselves as White (73%, n = 310), Non-Hispanic/Latino (63%, n = 267) males (59%, n = 250). The mean age for our sample was 50.5 years. On average, patients had 6.4 office visits and 0.29 emergency room visits in the 12 months before filling out the survey. On average, patients saw 1.5 providers during that same period. See Table 3 for complete details on the distribution of each demographic variable.

QGEN10 answers ranged from 0 to 5 with varying missingness. The mental composite score averaged 50.7 (sd = 7.5, range = 26.8–61.9). 17% (n = 63) met the at-risk criteria (≤ 43.2) by our calculation. The Physical composite score averaged 50.2 (sd = 7.8, range = 25.7–61.4). 17% (n = 64) met at-risk criteria (≤ 42.4). 31% (20 patients) at risk based on the physical composite score were also at risk based on the mental score.

The average count of chronic conditions was 1.6 (range 0–8). The most commonly endorsed chronic condition in our sample was major depressive disorder (n = 102, 24%). The highest QDIS impact appeared among patients who endorsed major depressive disorder (mean impact ranking = 2.0, sd = 1.2). See Tables 4 and 5 for complete details on the distribution of each QGEN and QDIS question.

Bivariate analysis

Several of the demographic factors showed a significant relationship with either the physical or mental composite scores or both. See Table 3 for complete details.

Each of the ten QGEN questions was significantly associated with mental and physical composite scores (p < 0.001). 3 of the chronic conditions in our QDIS checklist demonstrated a significant relationship with mental risk level, and 7 were significantly associated with physical risk level. A raw count of chronic conditions was significantly associated with both mental (p = 0.014) and physical composite scores (p < 0.001). See Tables 4 and 5 for complete details.

Impact rankings of major depressive disorder and ulcerative colitis demonstrated a significant relationship with the mental composite score (p = 0.001 and 0.008, respectively). Impact rankings from the following conditions were significantly associated with physical composite scores: lower limb osteoarthritis (p = 0.003), sciatica (p = 0.004), major depressive disorder (p = 0.016), and cancer (p = 0.04). Total impact score was significantly associated with the physical composite outcome (p < 0.001).

Several of the individual QGEN questions demonstrated strong positive relationships with each other and with either or both composite scores. No strong correlations were detected between the eHR-based variables and the individual QGEN questions or composite scored outcomes. Figure 1 displays strong correlations (greater than or equal to the absolute value of 0.6) amongst the numeric predictors and outcome variables.

Classification algorithms

All 5 tree-based approaches fit to classify mental risk demonstrated similar results, with QGEN Q8 and Q9 as predictive frontrunners. All algorithms other than the xgboost and neural network identified Q8 as the feature with the highest importance. Question #8 asks how happy or satisfied one has been with their life, with response options ranging from extremely happy to very unhappy. QGEN question #9 asks how easy or hard emotional health makes one’s work activities with response options ranging from very easy to unable to do. Patient responses that they were more often unhappy/dissatisfied or very unhappy/dissatisfied most of the time were associated with reduced mental QoL, as were patient responses that it was ‘very hard’ or they were ‘unable’ to conduct their daily activities because of how they feel emotionally. A reduced 2-item model was fit for each algorithm using only questions 8 and 9 as predictors. Performance on the holdout partition demonstrated balanced accuracy between 79 and 98%, depending on the specific approach. The highest balanced accuracy achieved was 0.98 from the random forest and the Bernoulli boosting algorithms. All 5 approaches fared significantly better than the no-information rate (0.83). Tree-based approaches to classify physical risk demonstrated more variability in the top predictive features overall, though Q2, Q3, and Q4 were consistently ranked as the most important. Question #2 asks how easy or hard it has been to do one’s regular physical activity (walk, climb), with response options ranging from very easy to unable to do. Question #3 asks how much pain limited one’s everyday activities or QOL, with response options ranging from no pain to extremely limited. Q4 asks patients how easy or hard it has been to do regular work or home activities. Patient responses that their physical health made it ‘very hard’ or they were ‘unable’ to do their physical activities or work/home activities were associated with reduced physical QoL, as were patient responses indicating that they were ‘limited a lot’ or ‘extremely limited’ by their pain. A 2-item decision model using questions 2 and 3 was applied to the test sample, resulting in estimates of balanced accuracy between 76 and 94% for individual algorithms. The highest balanced accuracy achieved was 0.94 from the neural net and the Adaboost algorithms. All algorithms performed better than the no-information rate (0.77). The top 5 predictor variables and individual algorithm performance metrics can be found in Table 6.

The algorithms predicting mental composite scores generally had higher balanced accuracy. More variability in top predictors coupled with lower performance for the fitted model could suggest that physical risk for diminished quality of life is more nuanced than mental risk, perhaps necessitating more complex model parameters.

Discussion

Health-related quality of life is a dynamic concept uniquely impacting each individual. QoL dimensions are among the most often identified by patients when asked about desired health outcomes.42 Patients with chronic medical conditions’ self-assessment of their function and well-being can predict their use of health resources and resulting morbidity and mortality. Thus, HRQoL assessment and intervention within the primary care setting, where most individuals receive their care, would make great sense.

To that end, an easily-initiated and highly predictive measure could greatly benefit PC providers. Preliminary results from the current study suggest that a brief, 4-question measure may predict physical and mental quality of life nearly as accurately as the full 40-question QGEN-10 and QDIS surveys combined. If this predictive validity is confirmed in larger samples, it could lead to significant restructuring and simplifying of QoL measurement, resulting in increased adoption by primary care providers and integration into everyday workflows.

The causal functions that drive the predictive capability of the most influential questions in our survey warrant further investigation. We cannot state definitively what makes QGEN questions 2,3,4,8, and 9 more predictive than others. However, recent evidence suggests that a single question may be enough to capture some QoL domains adequately43.

Next steps

We plan to generate a rapid-cycle learning community with additional practices to validate further and scale up these predictive algorithms to generalize our methodology. We have enlisted 4 additional primary care sites to collect QGEN and QDIS data. Patients from these sites are expected to be more representative of the general population. Future studies using a larger, more diverse sample may enhance the generalizability of the results while validating the algorithm in different settings and patient populations. Demographics and SDoH factors were not highly predictive in our pilot study. Data from additional, diverse patients may improve their predictive capacity.

Ultimately, we aim to automate a pipeline that uses demographic and eHR data to identify potentially at-risk patients who can be electronically outreached to collect the most predictive QGEN questions described above. This reduces the up-front need for human effort to collect data prospectively. Patient responses from the QGEN will be fed to providers through the eHR in a custom manner to befit their existing workflows. This makes HRQoL risk data available to clinicians in a way that allows them to make an informed recommendation for patient disposition. This next phase of the work is necessary but not sufficient. Concurrently with our psychometric efforts needs to be the definition and implementation of clinical workflows that identify the requisite care needs of patients in the different risk categories.

Limitations

Algorithms generated for this pilot study are based on a small, convenience sample, which can result in selection and/or non-response bias. Due to missingness and lack of variation in our pilot sample, several patient demographic variables needed to be collapsed into fewer categories before modeling. This reduces the information available to the algorithms and may introduce bias. Additionally, overfitting is a common concern for decision trees. While ensemble methods such as gradient boosting aim to address such issues, our models likely remain overfit.

Furthermore, while our response rate was relatively high and the sample relatively diverse, the results must be interpreted cautiously as they may not represent all PC patients. For example, our sample was mainly healthy compared to the national norms, and thus, our predictive findings may not represent PC patients with multi-morbidities.

Preliminary results from this study are promising, however, prospective validation in real-world clinical settings is needed to ensure that the algorithm performs well in practice and can be effectively integrated into clinical workflows. This is necessary to further delineate the robustness and applicability of our preliminary findings.

Future work needs to focus on the integration of these tools into existing electronic health record systems and clinical workflows to maximize their downstream impact on patient care. There are many barriers and challenges to integrating risk prediction tools into the eHR, and we recommend a more formal investigation of these in the future.

Conclusions

We are fast approaching the use of artificial intelligence as a clinical tool in health care. Supervised machine learning can be used to restructure QoL measurement to reduce the burden of prospective data collection, which can be built into a multi-data source risk prediction. Prediction alone is not enough to impact care delivery and outcomes; such predictive data must translate into usable workflows if such efforts are to translate into regular use to guide and enhance clinical practice and impact patient care delivery and outcomes.

Data availability

Due to the nature of the research and copyright on quality of life screening questions used for prediction, supporting data is not available in full; however, a partial dataset including QGEN10 question stems and response category ranges may be available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Sitlinger, A. & Zafar, S. Y. Health-related quality of life: The impact on morbidity and mortality. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 27, 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soc.2018.05.008 (2018).

Pinheiro, L. C. et al. Using health-related quality of life to predict cardiovascular disease events. Qual. Life Res. 28, 1465–1475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02103-1 (2019).

Ul-Haq, Z., Mackay, D. F. & Pell, J. P. Association between physical and mental health-related quality of life and adverse outcomes; a retrospective cohort study of 5,272 Scottish adults. BMC Public Health 14, 1197. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1197 (2014).

Kanatas, A., Lowe, D. & Rogers, S. N. Health-related quality of life at 3 months following head and neck cancer treatment is a key predictor of longer-term outcome and of benefit from using the patient concerns inventory. Cancer Med. 11, 1879–1890. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.4558 (2022).

Efficace, F. et al. Is a patient’s self-reported health-related quality of life a prognostic factor for survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients? A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors of EORTC study 08975. Ann. Oncol. 17, 1698–1704. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdl183 (2006).

Siersma, V. et al. Health-related quality of life predicts major amputation and death, but not healing, in people with diabetes presenting with foot ulcers: the Eurodiale study. Diabetes Care 37, 694–700. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-1212 (2014).

Mapes, D. L. et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization: The dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS). Kidney Int. 64, 339–349. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00072.x (2003).

Li, C. L. et al. Joint predictability of health related quality of life and leisure time physical activity on mortality risk in people with diabetes. BMC Public Health 13, 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-67 (2013).

Abbott, J. et al. Can health-related quality of life predict survival in adults with cystic fibrosis?. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 179, 54–58. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200802-220OC (2009).

Tsai, S. Y., Chi, L. Y., Lee, C. H. & Chou, P. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 22(1), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-006-9092-z (2007).

Parkerson, G. R. Jr. & Gutman, R. A. Health-related quality of life predictors of survival and hospital utilization. Health Care Financ. Rev. 21(3), 171–184 (2000) (PMID: 11481754).

Seid, M., Varni, J. W., Segall, D. & Kurtin, P. S. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of pediatric healthcare costs: A two-year prospective cohort analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2, 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-2-48 (2004).

Ware, J. E., Harrington, M., Guyer. R. & Boulanger, R. A system for integrating generic and disease-specific patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures. Patient reported outcomes (pro) newsletter. Fall (2012).

Ware, J. E., Gandek, B., Guyer, R. & Deng, N. Standardizing disease-specific quality of life measures across multiple chronic conditions: Development and initial evaluation of the QOL disease impact scale (QDIS®). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 14, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0483-x (2016).

Cheng, Y., Wang, F., Zhang, P., Xu, H. & Hu, J. Risk prediction with electronic health records: A deep learning approach. In SIAM International Conference on Data Mining SDM, vol 16 (2015).

Goldstein, B. A., Navar, A. M., Pencina, M. J. & Ioannidis, J. P. Opportunities and challenges in developing risk prediction models with electronic health records data: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 24(1), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocw042 (2017).

Hayes-Larson, E. et al. Racial/ethnic differences in health-related quality of life in persons with and without dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 69, 629–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16908 (2021).

Pate, C. A., Zahran, H. S. & Bailey, C. M. Impaired health-related quality of life and related risk factors among US adults with asthma. J. Asthma 56, 431–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2018.1466314 (2019).

Puciato, D., Rozpara, M., Bugdol, M., Borys, T. & Slaby, T. Quality of life of low-income adults. Work 74, 631–648. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-211110 (2023).

Jia, H., Zack, M. M. & Thompson, W. W. Population-based estimates of decreases in quality-adjusted life expectancy associated with unhealthy body mass index. Public Health Rep. 131(1), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491613100125 (2016).

Karri, R., Chen, Y. P. & Drummond, K. J. Using machine learning to predict health-related quality of life outcomes in patients with low grade glioma, meningioma, and acoustic neuroma. PLoS One 17, 5. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267931 (2022).

Pinto, M. et al. Quality of life predictors in patients with melanoma: A machine learning approach. Front. Oncol. 12, 843611. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.843611 (2022).

Liao, W. W., Hsieh, Y. W., Lee, T. H., Chen, C. L. & Wu, C. Y. Machine learning predicts clinically significant health related quality of life improvement after sensorimotor rehabilitation interventions in chronic stroke. Sci. Rep. 12, 11235. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14986-1 (2022).

Ware, J. E. & Sherbourne, C. D. The MOS 36-ltem short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 30, 473–483 (1992).

Ware, J. E. SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 25(24), 3130–3139 (2000).

Ware, J. E. Jr. Improvements in short-form measures of health status: introduction to a series. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 61, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.08.008 (2008).

Pequeno, N. P., Cabral, N. L., Marchioni, D. M., Lima, S. C. & Lyra, C. D. Quality of life assessment instruments for adults: A systematic review of population-based studies. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01347-7 (2020).

Bullinger, M. & Quitmann, J. Quality of life as patient-reported outcomes: Principles of assessment. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 16, 137–145. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.2/mbullinger (2014).

McEntee, M. L., Gandek, B. & Ware, J. E. Improving multimorbidity measurement using individualized disease-specific quality of life impact assessments: Predictive validity of a new comorbidity index. Health Qual Life Outcomes 20, 108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-022-02016-7 (2022).

Lochner, K. A. & Cox, C. S. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries, United States, 2010. Prev. Chronic Dis. 10, E61. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.120137 (2013).

R: A language and environment for statistical computing. The R project for statistical computing (2021). Available at: https://www.r-project.org/. (Accessed: 3rd May 2024).

Standards for maintaining, collecting, and presenting federal data on Race and ethnicity. U.S. Department of the Interior (2015). Available at: https://www.doi.gov/pmb/eeo/directives/race-data. (Accessed: 3rd May 2024).

Uddin, S., Khan, A., Hossain, M. E. & Moni, M. A. Comparing different supervised machine learning algorithms for disease prediction. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 19, 1–16 (2019).

Bhavsar, H. & Ganatra, A. A comparative study of training algorithms for supervised machine learning. Int. J. Soft Comput. Eng. (IJSCE) 2, 74–81 (2012).

Mohmed, A. Comparative study of four supervised machine learning techniques for classification. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 7(2), 5–18 (2017).

Dwyer, K. & Holte, R. Decision tree instability and active learning. In Machine Learning: ECML 2007: 18th European Conference on Machine Learning, Warsaw, Poland, September 17–21, 2007. Proceedings 128–139. (Springer 2007).

Natekin, A. & Knoll, A. Gradient boosting machines, a tutorial. Front. Neurorobot. 7, 21 (2013).

Ferreira, A. & Figueiredo, M. Boosting algorithms: a review of methods, theory, and applications. In Ensemble Machine Learning (eds Zhang, C. & Ma, Y.) 35–85 (Springer, 2012).

Ranganathan, P., Pramesh, C. & Aggarwal, R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Logistic regression. Perspect. Clin. Res. 8(3), 148–151 (2017).

Sarker, I. Machine learning: Algorithms, real-world applications and research directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2, 3 (2021).

Finch, W. H. The impact of variable omission on variable importance measures of CART, random forest and boosting algorithms. J. Stat. Res. 55(2), 335–358 (2021).

Sherbourne, C. D., Sturm, R. & Wells, K. B. What outcomes matter to patients?. J. General Internal Med. 14, 357–363. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00354.x (1999).

Ware, J. E. Improved items for estimating SF-36 profile and summary component scores: construction and validation of an 8-item QoL general (QGEN-8) survey. Med. Care. (in press) (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the individuals and organizations who have contributed to the publication of this research paper. We thank our John Ware Research Group (JWRG) colleagues for their partnership and guidance. We thank the staff at MidValley Family Practice in Basalt, Colorado, for their assistance with data collection, as well as Constance Van Eeghen, Dr.PH., Mustafa Ozkaynak, Ph.D., George Runger, Ph.D., and Donald Nease Jr, Ph.D. for their valuable insights. We also acknowledge Figaro Loresto, PhD, RN, for his mentorship, guidance, and kindness.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: R.K., G.K., A.K., S.G.; data collection: A.K., G.K.; analysis and interpretation of results: S.G.; draft manuscript preparation: S.G., C.H.; Supervision, Revision of Final Draft & Resource Provision: J.F.T., R.K. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The authors declare that the Colorado Multiple Institute Review Board (CoMIRB) deemed this work exempt as secondary data analysis.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grim, S., Kotz, A., Kotz, G. et al. Development and validation of electronic health record-based, machine learning algorithms to predict quality of life among family practice patients. Sci Rep 14, 30077 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80064-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80064-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Using the cancer aging and research group- breast cancer (CARG-BC) predictive model in older adults (OA) with early breast cancer: an external validation study

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2026)

-

Medical laboratory data-based models: opportunities, obstacles, and solutions

Journal of Translational Medicine (2025)