Abstract

This study investigated the influence of Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean football players’ participation in European leagues on their national teams’ FIFA rankings from 2000 to 2024. Utilizing data from 22,972 matches featuring 392 players across 36 European leagues and 12 tournaments or cup competitions, survival and conditional process analyses were conducted to explore the relationships between expatriate player counts, appearances, playing time, and FIFA rankings. The results demonstrated a significant correlation between the number of expatriate players, particularly in top-tier leagues, and national team rankings. Notably, Japanese and South Korean players exhibited longer durations of participation and higher rates of advancement to elite European leagues compared to Chinese players. Furthermore, the conditional process analysis revealed an indirect effect of expatriate player count on FIFA rankings, mediated by increased appearances and playing time, with the strongest influence observed in the Big Five leagues. These findings underscore the importance of international exposure for advancing East Asian football and provide insights for policymakers on effectively nurturing young talents for international careers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

International talent mobility affects the human capital of source countries, presenting both challenges and opportunities. Initially, the departure of technical experts can deplete a nation’s human capital. Yet, over time, such migration could enhance human capital, earning it the monikers ‘brain drain’ or ‘brain gain’. The global football market, like the brain drain debate, is criticized for siphoning talent from football’s ‘developing countries’ , enriching ‘developed leagues’1,2. This critique often lacks evidence about its impact on national team performance.

First, scholars argue that the synergy of economic development, democratic experience, football association duration, and low income inequality improves the performance of men’s national football teams3,4,5. Similar key factors, such as economic development and talent pool, are also applicable to the performance of women’s national football teams6。Therefore, the phenomenon of players flowing to football-developed countries to participate in leagues is not sufficient to support the view that this will lead to a decline in football in countries that lose player talents.

Second, Football’s unique nature allows players to represent their national teams while playing for foreign clubs, unlike most technical professionals. Despite potential ‘muscle drain’ for clubs in ‘developing’ countries, their national teams gain from the experience of their players abroad2.

In Football, expatriate players are defined as footballers playing outside the association where they grew up, which they left after being recruited by a foreign club. This definition distinctly categorizes sports migration, emphasizing player movements specifically associated with the sport of football7.

The prevalence of professional football clubs employing expatriate players has surged. According to statistics, foreign players in the top five European football leagues accounted for 20% of the total number of players in 1995. By 2005, this figure had risen to 39%. And by 2015, the percentage reached 50%8. Between 2017 and 2023, the global average of overseas players in professional teams increased by 20%, constituting about a quarter of players across 135 leagues. Brazil, with 1,289 expatriates, followed by France (1,033) and Argentina (905), led in the number of expatriate players, comprising 22.4% of the total international expatriate footballer population7. The study indicates that foreign players’ appearances significantly influence the success of surveyed clubs in their domestic leagues, with a notable effect in Continental competitions9,10. International player migration enhances national team performance, notably in nations with less competitive domestic clubs11. When players transfer to clubs and leagues of a higher standard than those in their home country, the enhancements in skill, physicality, experience, and mindset from their international exposure are reflected in the national team’s performance, contributing to an overall increase in its competitive level1,2,12. All nations featured in the top 15 for total PTBs(playing time benefits) of foreign players in the Big-5 leagues across the seasons from 2013/2014 to 2017/2018 are globally renowned football clubs. Research indicates that expatriate players’ playing time and scoring contributions differ among leagues, peaking in Germany’s Bundesliga. Additionally, countries in the top 15 for total PTBs have qualified for either the 2014 or 2018 FIFA World Cup Finals13. The positive impact of player migration on international sporting performance in women’s football has also been confirmed14.

Fieldwork has shown that elements like power dynamics, communication, recruitment, player development, coaching strategies, player release, and team culture are crucial to the daily professional footballer’s experience15. Scholars highlight the crucial role of family and club support in aiding players’ adaptation to new social, cultural, and football environments16,17,18,19,20,21,22, as well as their psychological well-being, during overseas assignments23. Beyond Europe’s top-tier leagues, players often face challenges such as short-term contracts, substandard housing, isolation, and the ever-present risk of career-ending injuries24. Although some footballers perceived the signing of foreign players as a potential obstacle to their career advancement, researchers did not find a significant operational impact. This is likely because all participants had equal opportunities to play competitively15. Another unique form of expatriation involves player naturalization and dual nationality, providing footballers with more opportunities and choices but potentially raising questions about national loyalty25.

Essentially, while players cross international boundaries, it is the clubs, rather than the nations, that define their scope26. The study of expatriate player destinations encompasses not only Europe but also extends to East Asia27, Central Asia28, and Southeast Asia29. Scholars found a significant impact of foreign players on team performance30, but football clubs are confronted with the challenge of having players who speak different languages and who have different football philosophies ingrained in them31. So player migration routes between footballing cores and peripheries frequently stem from cultural affinities and a common colonial history32. Latin American players often initiate their European football careers in Portugal or Spain, and clubs in Belgium and France commonly recruit from French-speaking African nations32,33. The primary challenges, as noted in player interviews, were not associated with the initial migration or club tenure, but with the prospects for internal advancement to the first team.34. However, there is a scarcity of research on where East Asian footballers typically commence their overseas football careers. This lack of studies may be attributed to the fact that East Asian countries do not share the same profound cultural, historical, and linguistic ties with foreign countries, especially European nations, as Latin American and African countries do.

China, Japan, and South Korea, three countries in East Asia, share great similarities in culture, history, and ethnicity. These three nations frequently interact and learn from each other across various social spheres, including sports. However, since 2000, the gap in the performance levels of the Chinese men’s national football team compared to the Japanese and South Korean men’s national teams has been widening (hereafter referred to as ‘Chinese men’s team’, ‘Japanese men’s team’ and ‘South Korean men’s team’). As of July 2024, Japanese and South Korean men’s teams are ranked 18th and 23rd in the FIFA world rankings, respectively, and 1st and 3rd in Asia. In contrast, Chinese men’s team is ranked 87th in the world and 13th in Asia35. The study found that experience has a significant positive impact and the strongest correlation with FIFA ranking points36. Good experience can only be accumulated in high-quality football matches and training environments. Undoubtedly, Europe has the best football matches and training environments. Therefore, Chinese media and fans widely believe that a major reason for the poor results of the Chinese men’s national team is the decreasing number of Chinese players playing in the most developed European leagues. In contrast, Japan and South Korea have continuously increased their overseas representation, allowing their national teams to significantly surpass China’s level. After qualifying for the 2002 FIFA World Cup, Chinese men’s team has failed to reach the World Cup finals for five consecutive tournaments over the past 20 years. At the 2023 Qatar Asian Cup, Chinese men’s team was eliminated in the group stage, marking their worst performance in the past two Asian Cups over the last 10 years. Meanwhile, Japan and South Korea have consistently advanced to the round of 32 and progressed from the group stage in recent FIFA World Cups.

Although Western scholars have conducted extensive research on expatriate footballers and their contributions to national teams, studies examining the widening gap between the Chinese men’s team and the Japanese and South Korean men’s teams from the perspective of expatriation are relatively rare in East Asian academia. Unlike Japan and South Korea, which jointly hosted the 2002 FIFA World Cup and took this as an important opportunity to start a decades-long period of football prosperity, the Chinese government had not issued the "Overall Plan for Chinese Football Reform and Development" until 2015. Scholars believe this delay resulted from a series of problems, such as the failure of previous policy attempts to improve Chinese football and the increasingly critical national mood towards football, which intertwined before this major change was brought about37. However, as of 2024, the changes brought about by this policy for the development of Chinese football remain limited. In fact, at the outset of the 2015 reform, some interviewees did not hold a positive attitude towards the prospects of Chinese football reform38. Discussions on China’s football reform strategies have continued in recent years, addressing issues like historic path dependency39 and a number of policy conflicts that restrict an effective implementation of the youth football policies40. It was around 2015 when China embarked on a ‘money-driven football’ model. Clubs invested vast sums to recruit high-level foreign players, which rapidly elevated the competitive level of Chinese football clubs and led to two victories in the AFC Champions League. World-class players such as Didier Drogba, Paulinho, Oscar, Marouane Fellaini, and Hulk joined the Chinese league, leading Chinese fans to jokingly refer to China as the "world’s sixth league," alongside the top five European leagues. However, despite the club-level success, the performance of the Chinese men’s national team remains unsatisfactory and falls short when compared to strong Asian teams like Japan and South Korea. This demonstrates that the short-term impact of high-level foreign players in the Chinese league does not translate into success for native players at the national team level in competitions against other Asian countries.

Some scholars have used Japanese and South Korean football as case studies, analyzing their campus football systems and policy configurations, and proposing strategies for Chinese players to ‘go global’41,42. Others have reviewed the history of Chinese football player expatriation, summarizing the reasons for the low quality of overseas experiences 43. While these articles provide a foundation for the current research, they may be limited by their timeliness, as they were published around 10 years ago, or by their focus on macro-level suggestions and experience summaries for expatriation. The current analysis of the ‘one falls as the others rise’ phenomenon among the Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean men’s football teams from the perspective of expatriation has not yet been comprehensive or clear, and continues to lack a thorough quantitative comparison.

This study aims to examine the data of expatriate football players from China, Japan, and South Korea during their European careers, assessing how their international experience influences their national teams’ performance. The emphasis on Europe reflects its status as the epicenter of competitive and prestigious football, with leagues like the Premier League, La Liga, Bundesliga, Serie A, and Ligue 1 setting the global standard. The higher number of East Asian players in Europe offers a substantial sample for analysis, enhancing the study’s statistical significance and applicability. This research seeks to offer East Asian nations critical insights for their football strategy development.

Materials and methods

The dataset incorporates a detailed compilation of 22,972 matches, accumulating a total of 1,397,973 min of gameplay since 2000. Specifically, it encapsulates performance metrics for 54 Chinese, 102 South Korean, and 236 Japanese players. Moreover, the scope of this dataset extends to 36 European football leagues and encompasses 12 prestigious championships or cup competitions, both intercontinental and domestic, thereby offering a comprehensive overview of competitive football dynamics across varying geographical scales. The research utilized the FBref.com database, which is supported by Opta Sports and renowned for its accuracy. Its widespread application across betting, media, and professional sports analysis industries underscores its reliability44. The database’s reliable data has underpinned a multitude of football studies and significantly contributed to global academic discourse in football45,46,47,48,49. Despite potential gaps in the historical records of individual East Asian players’ overseas careers spanning past decades, the authority of this database is universally acknowledged within both the football community and academia. The database’s inclusion of representative samples of overseas players from these nations enables robust trend analysis and fosters informed scientific discourse.

The performance of the Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean men’s teams is based on the FIFA World Rankings (hereafter referred to as “FIFA Rankings”) since 2000. In December 1992, FIFA first published a ranking list for comparison. Despite controversies surrounding the ranking algorithm, it has been used for seeding and group allocation in major tournaments like the World Cup and the Asian Cup. In August 2018, a new ranking model named “SUM” took effect. It adds/subtracts game points won/lost to/from previous totals rather than averaging points over time. The added/subtracted points are partly determined by opponents’ relative strength, expecting higher-ranked teams to fare better against lower-ranked ones50. Our study’s national team ranking data rely on different algorithms before and after 2018, but since each team’s ranking in different eras depends on the same algorithm for that era, it doesn’t affect the fairness and authority of our comparison of the men’s teams of three countries.

All data acquisition and the analysis of match data did not involve any additional testing or human experiments. The entire research was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

This study presents a descriptive analysis of the comprehensive data regarding the European expatriation of Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean football players. The analysis delves into the distribution of expatriation destinations, the trajectories and ages at the time of expatriation, the ‘survival probability’ of overseas careers, types of competitions played, and how these factors relate to the FIFA rankings of their respective nations. When examining the expatriation routes of Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean players, we initially assessed data normality for each pair of groups using the Shapiro–Wilk test and evaluated the homogeneity of variances with the Levene test. If the data from each pair of groups complied with a normal distribution and variance homogeneity was established, an independent samples t-test was conducted; otherwise, a Welch’s t-test was applied. Where at least one group did not adhere to a normal distribution, a Kruskal–Wallis H test was performed. Considering the involvement of the same data in multiple pairwise comparisons, we adjusted the p-values for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction. For independent samples t-tests, including Welch’s t-tests, Cohen’s d is used as the effect size measure, while Eta-squared is used for the Kruskal–Wallis H test. Additionally, according to Hayes, when the indirect effect of independent variable X on dependent variable Y through variable M changes due to the moderation of variable W, the relationship between X and Y can be considered a conditional process51. In the process of players’ expatriation, it is the players who contribute to the FIFA rankings. Therefore, this study considers the number of expatriate players as the independent variable X, the FIFA ranking as the dependent variable Y, and the number of appearances and playing time as mediating variables M. Based on this, a parallel mediation analysis is established, suggesting that the number of expatriate players influences the FIFA ranking through the number of appearances and subsequently through playing time. Furthermore, the type of competition is considered a moderating variable that influences the number of appearances and playing time, and may also directly impact the FIFA ranking. Accordingly, the following hypothetical model is proposed, as shown in Fig. 1.

Results

Distribution and trends of East Asian football players in European leagues

The study analyzed the distribution of Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean footballers in European countries since 2000. Each player’s experience is tallied once per country, irrespective of whether they have participated in distinct leagues within the same country or spanned multiple seasons within that nation’s football ecosystem. This method accurately reflects the distribution of players and prevents double counting. Each player was assigned a unique ‘player ID’ and grouped according to the country of the league in which they played during different periods. The total number of unique players in each country was then summed to determine the overall player distribution for that country.

Since 2000, Germany has been the most popular destination for South Korean and Japanese players, with 32 and 77 player appearances, respectively. Belgium and Spain are also common destinations for players from both countries. Japanese players have more experience in the Netherlands and Portugal, while South Korean players often move to France and England. Chinese players, in contrast, have mainly focused on Spain, England, and Portugal, but their numbers are significantly lower compared to those from South Korea and Japan. Chinese players have played in 17 European countries, while South Korean and Japanese players have ventured into 23 and 24 countries, respectively (Table 1).

Table 2 shows that since 2000, the German Bundesliga has been the most common destination for South Korean and Japanese players, with 28 and 52 player appearances, respectively. Besides the Bundesliga, South Korean players have mainly played in the Premier League, Ligue 1, and the top leagues of countries like Croatia. Japanese players have more frequently joined the top leagues in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Portugal. Chinese players have primarily played in the top leagues of Portugal, England, and Germany. The second-tier leagues in England and Spain have also welcomed a significant number of East Asian players.

Regarding age, South Korean players joined the Bundesliga at an average age of 22.04 years, while Japanese players joined the Eredivisie at an average age of 22.12 years. Chinese players had the lowest average age when joining the Eredivisie, at 20 years old. Across all European leagues, the average age of Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean players was 22.81, 23.87, and 23.26 years, respectively.

Positional analysis of East Asian football players in European leagues

In terms of positional distribution, since 2000, European leagues have featured 519 forwards, 332 midfielders, and 314 defenders from China, Japan, and South Korea. The top five European football leagues (hereinafter referred to as ‘the Big Five’)—the first-tier leagues in England, Spain, Germany, Italy, and France—are renowned for their global reputation and ability to attract world-class talent, representing the highest level of competitive football25,42. Playing in the Big Five is a testament to a player’s abilities, and they can also bring the experience gained in these leagues back to their national teams. There is a significant difference in the number of Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean players accepted by the Big Five leagues compared to non-Big Five leagues. In addition to 255 forwards, the Big Five leagues have preferred 147 defenders. From a national perspective, China has exported more defenders (43) compared to forwards (38). In contrast, Japanese and South Korean players are mostly forwards (Fig. 2). Although historical data on goalkeepers playing in European leagues exist, they are not discussed in this article due to the small sample size of goalkeepers.

Expatriation routes and career progression of East Asian football players in Europe

Our study tracked the transfer history of East Asian players, dividing their expatriation routes into three categories: Type A, Type B, and Type C, based on whether they first entered the Big Five or not. For Type A players, the study recorded information about the first non-Big Five league they played in and their subsequent first transfer to a Big Five league. A1 represents their first entry into a non-Big Five league, while A2 represents their later transfer from a non-Big Five league to a Big Five league. For Type B players, the study recorded information about the Big Five they directly joined. Type C players are those who have always played in non-Big Five during their time in Europe.

The adjusted p-values indicate that there are no significant differences in the ages of Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean players at various stages of their expatriation careers, with the exception of the comparison between Chinese and Japanese players in Route C, which yields a p-value of 0.0197 and a substantial effect size of -0.510652. The median age of Chinese players directly joining non-Big Five leagues without subsequently joining the Big Five is 21.00 years, while for Japanese players it is 23.00 years. Effect sizes suggest that although differences in age among the countries are present in magnitude, these differences are not always statistically significant, particularly in Routes A1, A2, and B.

Regarding the distribution of career routes (Fig. 3), 24.62% of South Korean players and 16.15% of Japanese players successfully entered the Big Five leagues through the A1-A2 transition. In contrast, only 11.90% of Chinese players achieved the same milestone.

Table 3 demonstrates that there is a significant difference in the years of service on Route C between Chinese players, with an average of 1.51 years, and Japanese players, with an average of 2.46 years. In contrast, no significant differences are observed between Chinese and South Korean players or between Japanese and South Korean players. The effect size values indicate that although statistically significant differences exist, their practical significance may be limited, particularly in the comparison between Japanese and South Korean players.

“Survival analysis” of East Asian football players’ careers in European leagues

Employing survival analysis methods, this study evaluated the ‘survival probability’ of Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean players within European leagues, employing the Kaplan–Meier estimator for each demographic’s survival probabilities. For the purposes of this study, ‘survival time’ is defined as the duration from a player’s debut in a European league to their departure from European competition. The log-rank test assessed the statistical significance of differences in survival curves among the countries. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Fig. 4) show that, overall, Japanese and South Korean players have higher survival probabilities than Chinese players. In the first year, the survival probability of players from all three countries is close, at over 65%. Nonetheless, the survival probability for Chinese players declines more rapidly over time compared to South Korean and Japanese players. By the fourth year, the survival probability of Chinese players drops to 8%, while the survival probability of South Korean and Japanese players remains above 22%. Notably, Japanese players exhibit a higher survival probability than South Koreans for the initial six years; however, post the sixth year, South Korean players’ survival probability slightly surpasses that of the Japanese. The log-rank test confirms that the disparities in survival curves between Chinese players and the collective of South Korean and Japanese players are statistically significant (p = 0.001), whereas the variance between South Korean and Japanese players does not reach statistical significance (p = 0.683).

Nevertheless, the disparities in survival periods among players from these three nations within the Big Five are insignificant, with South Korean and Japanese players alternating in leading the survival probabilities over time. In contrast, when considering leagues outside the Big Five, Japanese players exhibit a notably higher survival probability in comparison to both Chinese and South Korean players (p < 0.05). Alternatively, the survival probabilities between Chinese and South Korean players do not differ significantly (p = 0.155).

Utilizing Fbref.com’s position classification, we analyzed the survival probabilities for East Asian players across various positions, revealing the following: For forwards in the Big Five, a significant disparity exists between Chinese and South Korean players (p = 0.0117), favoring the latter with a more extended European career span; Among midfielders in non-Big Five leagues, significant differences emerge between Chinese and Japanese players, as well as between South Korean and Japanese players (p < 0.05), with Japanese midfielders far outlasting their Chinese and South Korean counterparts; Defenders from China experience a significantly shorter survival period in non-Big Five compared to their South Korean and Japanese peers (p < 0.05), whereas no significant distinction is observed between the latter two. Additionally, for forwards in the Big Five, a marginal difference exists between Chinese and Japanese players (p = 0.0637), and a similar trend is observed for midfielders (p = 0.0816), indicating a potential trend rather than a statistically significant one.

Correlation between FIFA rankings and East Asian football players’ performance in European leagues

Figure 5 presents the changes in key data related to the FIFA rankings, number of European-based players, and appearances for China, Japan, and South Korea. It reveals a noticeable gap between China and the other two countries in these aspects. When categorizing the leagues into the Big Five and non- Big Five, the ranking order of Japan, South Korea, and China remains the same in terms of the number of players. From a trend perspective, since around 2009, the number of Japanese players playing in Europe has significantly increased, reaching 114 players by 2022 (21 in the Big Five and 93 in non-Big Five). During the same period, the number of Chinese and South Korean players playing in Europe has been lower than that of Japan, but South Korea still surpasses China in this regard.

Since 2000, significant disparities have been observed in the total player appearances, starts, and playing time/90 min (calculated based on the standard 90 min per match, this metric reflects the number of games played by players during their time in Europe across different years) for East Asian footballers from China, Japan, and South Korea in European leagues.

The data shows that Japanese players significantly lead in all three statistical categories. In 2022, they made history by surpassing 1,731 total appearances, 1316 total starts, and playing the equivalent of 1299.5 full 90-min matches. South Korean players had the highest data in 2020. In that year, the total appearances were 399 matches, the total starts were 246 matches, which is equivalent to playing 250.2 effective 90-min matches. In comparison, the historical peak for Chinese players was in 2007, with 109 total appearances, 58 starts, and 70.6 effective 90-min matches.

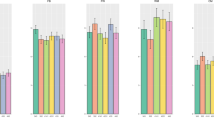

Figure 6 delineates the correlations between FIFA rankings, the count of expatriate players across leagues, and significant appearance metrics for China, Japan, and South Korea from 2000 to 2022. Employing Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant associations between the FIFA rankings and all six indicators (p < 0.01), albeit with varying directionalities. As shown in the figure, the FIFA rankings of China, Japan, and South Korea are most strong correlated with the number of expatriate players in the Big Five, exhibiting a relatively strong negative linear correlation (r = -0.5338). This suggests that a greater presence of expatriate players correlates with an enhanced FIFA ranking, reflected by a lower numerical ranking value. Despite being the weakest among the three nations, the correlation between FIFA rankings and the number of expatriate players in non-Big Five still measures -0.3927, surpassing the threshold for a weak correlation (≤ 0.2). Consistent with the expatriate player figures, the correlation between FIFA rankings and various appearance metrics is significantly associated (p < 0.01) across all three countries. The total appearances by expatriate players exhibit the strongest correlation with the FIFA rankings (r = -0.4931), preceded by the number of full 90-min matches (r = -0.4709) and the total starts (r = -0.4665), all indicating substantial negative correlations.

In addition to league matches, expatriate players generally represent their clubs in domestic cup competitions (such as the English FA Cup) and continental tournaments (such as the UEFA Champions League). The study classifies competitions into six categories: 1) the Big Five; 2) Non-Big Five; 3) UEFA Champions League (UCL); 4) other European competitions; 5) domestic lower-tier leagues; and 6) domestic cup competitions. Disaggregating expatriate players’ appearance data across these categories and assessing their correlation with the FIFA rankings of China, Japan, and South Korea yielded the results presented in Fig. 7. The analysis reveals significant correlations between all competition categories and the FIFA rankings of the three countries, with categories 1–4 demonstrating p-values less than 0.001. Appearances in the UCL show the strongest correlation with the FIFA rankings, with correlation coefficients’ absolute values exceeding 0.5. Subsequent are the Big Five, Non-Big Five, and other European competitions, with correlation coefficients’ absolute values above 0.4, signifying a robust negative linear relationship. Comparatively, correlations with domestic lower-tier leagues and cup competitions, while slightly weaker, remain significant (p < 0.01 for category 5 and p < 0.05 for category 6).

Conditional process analysis: East Asian expatriate players and FIFA rankings

According to the theoretical model proposed in the previous conditional process analysis, this study focuses on the indirect effects of the number of expatriate players (X) on the FIFA rankings (Y) through the number of appearances (M1) and playing time (M2), as well as the differences in these indirect effects across various competition categories (W). Table 4 indicates no significant direct effect of the expatriate player count or the number of appearances on FIFA rankings (p > 0.05). Conversely, playing time significantly and negatively affects the rankings (β = -0.0020, p = 0.0005), suggesting that increased playing time correlates with a higher FIFA ranking (lower numerical ranking value). The interaction between the expatriate player count and competition category does not significantly influence FIFA rankings (p > 0.05). Nevertheless, the expatriate player count significantly affects both the number of appearances and playing time (p < 0.001), with these impacts varying by competition category. However, neither the direct effect of expatriate players on FIFA rankings nor the indirect effect mediated by the number of appearances is significant. Significantly, the expatriate player count influences FIFA rankings indirectly through playing time (p < 0.001) and serially through both the number of appearances and playing time, with variations in this indirect effect observed across competition categories.

In assessing the direct and indirect effects of expatriate player count (X) on FIFA rankings (Y) across competition categories, the direct impact is largely non-significant, except for category 6, which exhibits a notable negative effect (β = -1.6595, p = 0.0250). The indirect influence through appearances on rankings is non-significant across all categories, with Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals (CI) including zero. Likewise, the indirect impact through playing time on the rankings is non-significant across all categories, with Bootstrap 95% CI including zero. The indirect effect of the number of players on the rankings through the serial mediation of the number of appearances and playing time is only insignificant in category 5, while it is significant in all other competition categories. The effect sizes are ranked as follows: the Big Five (|-0.2727|) > Non-Big Five (|-0.2383|) > other UEFA competitions (|-0.0594|) > UCL (|-0.0524|) > domestic cup competitions (|-0.0354|) > domestic lower-tier leagues (|0.3674|, insignificant). Notably, in the Big Five, an increase in the expatriate player count by one unit is projected to decrease the FIFA ranking value by 0.2727, via the mediation of appearances and playing time, suggesting a potential enhancement in team performance (Table 5).

The moderated mediation index reveals significant differences in conditional indirect effects (mediated by appearances and playing time) between the Big Five and other categories, with the exception of Non-Big Five (Bootstrap 95% CI excludes 0). These differences do not signify the absolute size of the conditional indirect effects for each category but are relative to those of the Big Five. In Non-Big Five, the anticipated improvement in FIFA ranking per additional expatriate player is 0.0344 less than in the Big Five, due to a smaller reduction in ranking value. Nonetheless, this difference is statistically insignificant, and the effect size is minimal. In other competition types, particularly category 5, the potential for increased expatriate players to enhance team strength via appearances and playing time may be attenuated. Within these competitions, an increase in expatriate players may not yield improvements in team strength as notable as those in category 1 (as illustrated in Table 6). The hypothetical model is thus supported.

Discussion

A pivotal strategy for Asian teams to elevate their national squads’ caliber is the deployment of players within European leagues for training and development 53. On September 5, 2024, the Chinese and Japanese men’s teams played a match in the Asian qualifiers for the 2026 World Cup. China suffered a crushing 0–7 defeat to Japan, and behind this result was the fact that none of the Chinese players were playing in foreign high-level leagues, while 21 of the Japanese players were.

Former Chinese men’s team captain, Xiaoting Feng, commented, "Japanese players have been playing in Europe for so many years, and what they experience is different from what we experience. It’s much more in-depth, with a faster pace in both matches and training. When they play against us, it’s like a professional team playing against an amateur team."54 The historical head-to-head record between Chinese and Japanese men’s teams shows that China has 7 wins, 8 draws, and 15 losses, with the last victory over their opponents dating back to 1998. At that time, players from both countries had not yet begun attempting to play in large numbers in high-level European leagues.

Over the past more than twenty years, the Japanese experience has proven that having more players playing in top European leagues, combined with the skills they develop during this period while facing high-level competition, gives the Japanese national team a huge advantage55. This trend is similarly evident in South Korea. Germany, specifically the Bundesliga, is the predominant destination for expatriate players from both Japan and South Korea, a pattern influenced by historical precedents. The ‘Kagawa Effect’ denotes the positive influence of Shinji Kagawa’s success in Germany on the subsequent European migration of Japanese players. Kagawa sparked a surge of Japanese players to Germany, with national team figures like Keisuke Honda and Shinji Okazaki bolstering German and other European clubs’ confidence to increase the recruitment of Japanese talent56. Consequently, Japan ranks among the top ten nations supplying players to the Bundesliga57. According to statistics from 2020, 1,047 Japanese players were active in various leagues worldwide, ranking Japan 9th globally and 1st in Asia in terms of internationalization of its football talent58. Similarly, typical cases of South Korean players going to Germany include Cha Bum-kun (1980s), Ahn Jung-hwan (2000s), and Son Heung-min (2010s), who were all leading figures in the South Korean national team of their respective eras and had a demonstrative effect on South Korean players playing in Germany. Despite Chinese players like Yang Chen and Shao Jiayi also playing in Germany, their influence in inspiring a similar wave of Chinese players was more constrained.

European leagues show a preference for East Asian forwards. Despite a scarcity of research comparing the skills and physical attributes of East Asian players to those of European, American, and African players, existing studies indicate: Asian youth players exhibit lower physical fitness indicators, including jumping ability, isokinetic strength for knee extension and flexion (notably at high velocities), and short-distance sprinting capabilities, when compared to European and African players59, non-Caucasian players have a significantly lower body fat percentage (9.2% ± 2.0%) than Caucasian players (10.7% ± 1.8%). However, relevant research suggests that although body composition is vital for elite footballers, the uniformity among top professional club players results in minimal individual variation60. European coaches perceive East Asian players, exemplified by the Japanese, as "technically proficient and energetic", possessing commendable "mental attributes, a strong work ethic, a desire for improvement, and an openness to coaching"61. Such characteristics align with European coaches’ expectations for East Asian forwards and enhance the team’s tactical repertoire.

Table 7 indicates that Chinese players who directly join non-Big Five leagues without subsequently joining the Big Five are younger than their South Korean and Japanese counterparts, suggesting that Chinese players are capable of reaching Europe at an earlier stage of their careers. However, the analysis of the international trajectories of East Asian players reveals that South Korean and Japanese players have a promotion probability exceeding 15% from Non-Big Five to Big Five leagues, significantly higher than the rate for Chinese players. This suggests that South Korean and Japanese players are more inclined to enhance their skills in Non-Big Five, subsequently earning opportunities in the Big Five. Furthermore, our research has revealed that Japanese players who have not been able to advance from non-Big Five to the Big Five have significantly more years of service in non-Big Five compared to their Chinese counterparts. These players may not be key members of the Japanese men’s team and may have never been part of the national squad, but their existence deepens the talent pool of Japanese football. Moreover, their presence in Europe can provide support to other Japanese players in terms of life and culture, thereby reducing some of the pressures associated with adapting to life and cultural differences when more Japanese players move to Europe20,21,22.

While the average age of initial entry into Non-Big Five does not significantly vary among East Asian players, Chinese players are older upon direct entry into the Big Five, with an average age notably higher than South Koreans. This may be related to the deficiencies in China’s youth training system for football and the limitations of the professional league level. Chinese players face a dearth of competitive challenges domestically, especially the professionalism of the young players among them has been discounted due to the protection of some competition policies, resulting in slower development62. Consequently, they tend to be at a more advanced age when reaching the prime age bracket for Big Five participation. The 2015 Chinese national football reform outlined an ambitious and promising vision for the development of Chinese football, particularly including the implementation of youth football policies 63. However, nearly a decade has passed, and the young players from that era have now become senior team players. Yet, their progress towards the heart of the football world, Europe, has almost come to a standstill. The performance of the best among them after joining the Chinese men’s team still fails to satisfy fans, and the gap between them and their peers from Japan and South Korea is growing larger. In addition to factors inherent to football, one of the biggest challenges facing the development of Chinese youth football is the historically low number of Chinese adolescents participating in the sport 64. This contrasts sharply with the vast population of China. This is a long-standing and real challenge for Chinese football, yet effective solutions have not been found over the decades. Chinese society is renowned for its intense “educational aspiration” or “educational ambition”65. Parents (and indirectly, schools) may wield more influence than football organizations (the Chinese Football Association and clubs) and are reluctant to allow participation in football to jeopardize their children’s education 40. This phenomenon may be more pronounced in China than in Japan or South Korea.

South Korean and Japanese players generally have longer professional careers in Europe compared to Chinese players. This finding aligns with the established benefits South Korea n and Japanese players possess regarding their overseas trajectories and tenure, substantiating their overall competitiveness over Chinese players. ‘Survival’ analysis indicates that while initial survival probabilities for players from these three nations exceed 65%, the probability for Chinese players declines more rapidly over time compared to South Korean and Japanese players. This suggests that Chinese players encounter heightened difficulties in acclimating to the European football milieu and sustaining their professional careers. The underpinning factors for this phenomenon encompass both football-specific elements and broader social and cultural dimensions, as observed among players from Asia29, Africa17, and across Europe16,21,24,34,66.

This implies that in promoting Chinese players to ‘go global’, there is a concurrent need to bolster comprehensive support and development, equipping them to navigate the challenges of international careers more effectively. Notably, Japanese players exhibit a higher survival probability than South Koreans in the initial 6 years, yet over time, South Korean players’ probability slightly exceeds that of the Japanese, highlighting unique attributes in the overseas experiences of these two nationalities. The aforementioned insights highlight the unique situations of the three countries, emphasizing the critical importance of charting a unique development route that is tailored to the needs of each country’s players.

The FIFA rankings for East Asian countries exhibit a significant negative correlation with the number of expatriate players and their appearance metrics, underscoring the pivotal role of these players’ volume and performance on national team outcomes. This corroborates findings from prior research by European scholars1,2,12. The correlation is strongest for expatriate players in the Big Five, underscoring these leagues’ significance in player development and national team construction as the most prestigious globally. Concurrently, indicators like total appearances, 90—minute matches played, and total starts also correlate negatively with FIFA rankings, indicating the importance of consistent playing time for expatriate players in Europe to be able to apply what they have learnt in training 67,and for bolstering their national teams’ competitiveness.

The findings from the conditional process analysis expose the underlying mechanisms and routes through which the number of expatriate players influences national team rankings. It is apparent that simply increasing the number of expatriate players does not directly translate to enhanced national team strength. The critical factor is the availability of stable playing opportunities and adequate game time for these expatriate players in their clubs, significant metrics for gauging their competitive level and career progression. Players can significantly enhance their technical and tactical abilities, physical parameters68, game comprehension, as well as psychological attributes through obtaining effective playing time in high-level matches.

The results also show that gaining opportunities to play and compete in the Big Five signifies that a player’s individual ability and professional quality have been recognized and honed at a world-class level. Such a competitive milieu substantially fosters player development, equipping the national team with a richer pool of elite talent. In other types of competitions, the enhancing effect of an increase in the number of expatriate players on the national team rankings is relatively weaker. Caution is advised when interpreting these outcomes, as the moderated mediation index reveals relative variations in indirect impacts across different competition categories. Internationalization efforts for players should consider optimal destination and competition selection to maximize opportunities for engagement and excellence in competitive, high-caliber environments. Research indicates that European youth national teams play up to three times more games than other global teams across all age groups69, primarily due to the innate nationality and geographical advantages European players have over their Asian and other regional counterparts. Consequently, facilitating direct participation of players in Europe emerges as an effective football development strategy for East Asian nations. However, echoing Arsène Wenger, FIFA Chief of Global Football Development, who noted that "Many talented youngsters waste their time on the benches of top teams instead of gathering experience on the pitch"70 ,the strategy of Japanese players joining non-Big Five merits consideration for East Asian countries. This approach not only allows Japanese coaches and players to gain new insights and experience high-level football training and matches without facing the intense competition of the Big Five, but also offers an opportunity to reassess the effectiveness of their previous strategies and to adjust their future approach accordingly71. For Chinese football, which is currently in the phase of catching up with Japan and South Korea, this strategy may be more realistic.

Conclusion

In the past two decades, the performance of East Asian football players in European leagues and the corresponding fluctuations in their FIFA rankings have formed an unprecedented controlled experiment. This study reveals that the participation of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean players in European leagues significantly enhances the FIFA rankings of their respective nations. A series of factors exert influence on this phenomenon, including number of expatriate players, playing time, and competition category, among others. The impact of these various factors on FIFA rankings is nuanced and varies. Over the same period, the performance metrics of Japanese and South Korean players in European leagues have been on an upward climb. Their respective national teams have benefited from the experience these players have gained while playing in Europe, which in turn has led to a continuous rise in their FIFA rankings. As a result, they have become formidable competitors in both the World Cup and the Asian Cup. In contrast, Chinese footballers’ participation in Europe significantly trails that of South Korea and Japan, with the national team’s performance disappointingly lagging, showing regression rather than progress over the past twenty years. The research findings offer references for East Asian countries to formulate supportive policies for football players to develop in Europe, especially for planning the career trajectories of young players pursuing football careers in Europe.

This study focuses on the data of Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean players in European leagues, excluding those with football careers in other regions such as South America and other Asian countries. While FIFA Rankings serve as a convenient and efficient basis for evaluating national team performance, further research could incorporate additional indicators, such as World Cup or Asian Cup competition results, to provide a more comprehensive assessment. It is also important to examine the promotional effect of foreign players on local talent and their impact on the national team’s performance following their integration into the leagues of China, Japan, and South Korea. Moreover, in an era where national teams, particularly in West Asia and Southeast Asia, are increasingly utilizing naturalized players, the potential for China, which has been conservative in recognizing naturalized players, to achieve rapid progress through this approach and the social criticism it may encounter, warrants further investigation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available on the official websites of each of the Big Five leagues, as well as on FBref.com, [https://fbref.com]. Further queries can be directed to the first author.

References

Allan, G. J. & Moffat, J. Muscle drain versus brain gain in association football: technology transfer through player emigration and manager immigration. Appl. Econ. Lett. 21, 490–493 (2014).

Berlinschi, R., Schokkaert, J. & Swinnen, J. When drains and gains coincide: Migration and international football performance. Labour Econ. 21, 1–14 (2013).

Wan, K.-M., Ng, K.-U. & Lin, T.-H. The Political Economy of Football: Democracy, Income Inequality, and Men’s National Football Performance. Soc. Indic. Res. 151, 981–1013 (2020).

Fan, M., Liu, F., Huang, D. & Zhang, H. Determinants of international football performance: Empirical evidence from the 1994–2022 FIFA World Cup. Heliyon 9, (2023).

Fan, M., Chen, X. & Zhang, H. An Analysis of Macro-influencing Factors of FIFA World Cup Competition Performance: Based on the SPLISS Theory Perspective. in Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Computer Science in Sport (IACSS 2023) (eds. Zhang, H., Lames, M., Baca, A. & Wu, Y.) 95–104 (Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, 2024).

Valenti, M., Scelles, N. & Morrow, S. Elite sport policies and international sporting success: a panel data analysis of European women’s national football team performance. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 20, 300–320 (2020).

CIES. Global study of football expatriates (2017–2023). https://football-observatory.com/IMG/sites/mr/mr85/en/ (2023).

Gerhards, J. & Mutz, M. Who wins the championship? Market value and team composition as predictors of success in the top European football leagues. Eur. Soc. 19, 223–242 (2017).

Varmus, M., Kubina, M. & Adamik, R. Impact of the Proportion of Foreign Players’ Appearances on the Success of Football Clubs in Domestic Competitions and European Competitions in the Context of New Culture. SUSTAINABILITY 12, 264 (2020).

Royuela, V. & Gásquez, R. On the influence of foreign players on the success of football clubs. Journal of Sports Economics 20, 718–741 (2019).

Lago-Penas, C., Lago-Penas, S. & Lago, I. Player Migration and Soccer Performance. Frontiers in psychology 10, 616–616 (2019).

Baur, D. G. & Lehmann, S. Does the mobility of football players influence the success of the national team? (2007) https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.980936.

Zhang, H. & Jiang, J. Evaluation of the Playing Time Benefits of Foreign Players in the Big-5 European Football Leagues. JOURNAL OF HUMAN KINETICS 84, 238–249 (2022).

Scelles, N. Policy, political and economic determinants of the evolution of competitive balance in the FIFA women’s football World Cups. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 13, 281–297 (2021).

Littlewood, M. The Impact of Foreign Player Acquisition on the Development and Progression of Young Players in Elite Level English Professional Football. (2005).

Maguire, J. & Pearton, R. The impact of elite labour migration on the identification, selection and development of European soccer players. Journal of sports sciences 18, 759–769 (2000).

Van Der Meij, N. Family matters in african football migration: an analysis of the role of family, agency and football academies in the mobility of ghanaian football players. (2015).

Richardson, D., Littlewood, M., Nesti, M. & Benstead, L. An examination of the migratory transition of elite young European soccer players to the English Premier League. JOURNAL OF SPORTS SCIENCES 30, 1605–1618 (2012).

Cleveland, T. Following the ball: African soccer players, labor strategies and emigration across the Portuguese colonial empire, 1949–1975. Cadernos de Estudos Africanos 15–41 (2013) https://doi.org/10.4000/cea.1109.

Leeds, M. A. & Marikova Leeds, E. International soccer success and national institutions. Journal of Sports Economics 10, 369–390 (2009).

Krizaj, J., Leskosek, B., Vodicar, J. & Topic, M. D. Soccer players cultural capital and its impact on migration. Journal of Human Kinetics 54, 195–206 (2016).

Darpatova-Hruzewicz, D. & Book, R. T. Applying a relational lens to ethnographic inquiry: Storied insight into the inner workings of multicultural teams in men’s elite football. PSYCHOLOGY OF SPORT AND EXERCISE 54, 101886 (2021).

Agergaard, S. & Ryba, T. V. Migration and career transitions in professional sports: transnational athletic careers in a psychological and sociological perspective. Sociology of sport journal 31, 228–247 (2014).

Oliveira Filho, J. H. de. Sports migrants in ‘Central’ and ‘Eastern’ Europe: beyond the existing narratives. Vibrant: Virtual Brazilian Anthropology 17, e17704–e17704 (2020).

Silva, D. V. da, Rigo, L. C. & Freitas, G. da S. Considerações sobre a migração, a naturalização e a dupla cidadania de jogadores de futebol. Revista da Educação Física / UEM 23, 457–468 (2012).

Rial, C. Rodar: a circulação dos jogadores de futebol brasileiros no exterior. Horizontes Antropológicos 14, 21–65 (2008).

MYUNG & lae, C. young. K league influx: Why do international footballers migrate to South Korea? Korean Journal of Sport Science 30, 729–745 (2019).

Myung, W. & Won, Y. Korean footballers’ exodus and its factors: Player migration to China and the Middle East. Korean Journal of Sport Science 30, 45–59 (2019).

MYUNG. South Korean male footballers’ involuntary labor migration: Why do they leave for Southeast Asia? Korean Journal of Sport Science 32, 242–255 (2021).

Scelles, N. & Khanmoradi, S. Impact of Market Value, Roster Size, Arrivals and Departures on Performance in Iranian Men’s Football. Sustainability 15, (2023).

Maderer, D., Holtbrügge, D. & Schuster, T. Professional football squads as multicultural teams: Cultural diversity, intercultural experience, and team performance. Int’l jnl of cross cultural management 14, 215–238 (2014).

Poli, R. Migrations and trade of African football players: historic, geographical and cultural aspects. Afrika Spectrum 41, 393–414 (2006).

Darby, P., Esson, J. & Ungruhe, C. African Football Migration: Aspirations, Experiences and Trajectories. (Manchester University Press, 2022). https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526120274.

Elliott, C. Football Labour Migration: An Analysis of Trends and Experiences of Northern Irish Players. (2017).

FIFA. Latest Men’s World Ranking. https://inside.fifa.com/fifa-world-ranking/men (2024).

Scelles, N. & Andreff, W. Determinants of national men’s football team performance: a focus on goal difference between teams. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing 19, 407 (2019).

Peng, Q., Skinner, J. & Houlihan, B. An analysis of the Chinese Football Reform of 2015: why then and not earlier?. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 11, 1–18 (2019).

Peng, Q., Skinner, J., Houlihan, B., Kihl, L. A. & Zheng, J. Towards Understanding Change-Supportive Organisational Behaviours in China: An Investigation of the 2015 Chinese National Football Reform. Journal of Global Sport Management 8, 817–837 (2023).

Peng, Q., Chen, S. & Berry, C. To let go or to control? Depoliticisation and (re)politicisation in Chinese football. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 16, 135–150 (2024).

Peng, Q., Chen, Z., Li, J., Houlihan, B. & Scelles, N. The new hope of Chinese football? Youth football reforms and policy conflicts in the implementation process. European Sport Management Quarterly 23, 1928–1950 (2023).

CHEN Xunan, YANG Shuo, LENG Tangyun, & ZHENG Fang. The Going - Abroad Phenomenon of Japanese and Korean Footballers :Group Characteristics , Dynamic Mechanism , and Implications. Journal of Chengdu Sport University 49, 127–134 (2023).

Wang Zhaoxin. A Comparative Study of Professional Football Players from China, Japan, and Korea Studying Abroad. Sports Culture Guide 66–69 (2013).

Cheng Long & Zhang Zhong. An Exploration of the Activities of Chinese Football Youth Training Abroad. Sports Culture Guide 112–115 (2015).

Li, C. & Zhao, Y. Comparison of Goal Scoring Patterns in ‘The Big Five’ European Football Leagues. Frontiers in psychology 11, 619304–619304 (2020).

Jamil, M. A case study assessing possession regain patterns in English Premier League Football. International journal of performance analysis in sport 19, 1011–1025 (2019).

Phatak, A. et al. Context is key: normalization as a novel approach to sport specific preprocessing of KPI’s for match analysis in soccer. Scientific reports 12, (2022).

Liu, H., Hopkins, W., Gómez, M. & Molinuevo, J. Inter-operator reliability of live football match statistics from OPTA Sportsdata. International journal of performance analysis in sport 13, 803–821 (2013).

Bilalic, M., Graf, M. & Vaci, N. The effect of COVID-19 on home advantage in high- and low-stake situations: Evidence from the European national football competitions. Psychology of sport and exercise 69, (2023).

Beato, M., Jamil, M. & Devereux, G. The Reliability of Technical and Tactical Tagging Analysis Conducted by a Semi-Automatic VTS In Soccer. Journal of Human Kinetics 62, 103–110 (2018).

FIFA. Revision of the FIFA / Coca-Cola World Ranking. https://digitalhub.fifa.com/m/f99da4f73212220/original/edbm045h0udbwkqew35a-pdf.pdf (2023).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis : A Regression-Based Approach. (Guilford Press, New York).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. (Routledge, 2013).

Rohith Nair. Klinsmann credits South Korean players who made step up to European leagues. https://www.reuters.com/sports/soccer/klinsmann-credits-south-korean-players-who-made-step-up-european-leagues-2024-01-14/ (2024).

After the Defeat. CCTV https://tv.cctv.com/2024/09/07/VIDEv7zqQDs3j3cjL84qHHEG240907.shtml?spm=C50326.PdSDUePAuwys.ELDpnADCKOfq.52 (2024).

FIFA. Three reasons behind Japan’s impressive form. https://www.fifa.com/fifaplus/en/news/articles/three-reasons-behind-japans-impressive-form (2023).

Shuichi, T. Football Dreams: Growing Number of Japanese Soccer Players Set Sights on Europe. https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/g02277/ (2023).

BUNDESLIGA. Why Japan and the Bundesliga are a perfect match. https://www.bundesliga.com/en/bundesliga/news/why-japan-and-the-bundesliga-are-a-perfect-match-kagawa-hasebe-kamada-okugawa-18590 (2023).

Drs Raffaele Poli, Loïc Ravenel, Roger Besson. Football players’ production index: measuring nations’ contributions. https://football-observatory.com/Football-players-production-index-measuring (2020).

Wong, D. P. & Wong, S. H. S. PHYSIOLOGICAL PROFILE OF ASIAN ELITE YOUTH SOCCER PLAYERS. JOURNAL OF STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING RESEARCH 23, 1383–1390 (2009).

Sutton, L., Scott, M., Wallace, J. & Reilly, T. Body composition of English Premier League soccer players: Influence of playing position, international status, and ethnicity. Journal of sports sciences 27, 1019–1026 (2009).

Daniel Storey. ‘Project DNA’: How Japan’s J1 League became a ‘flair factory’ for Europe’s top clubs. https://inews.co.uk/sport/football/project-dna-japan-league-flair-factory-europe-top-clubs-2184690 (2023).

Xinhua. Chinese Football Player of Year warns young players against complacency. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202101/22/WS600a4171a31024ad0baa46f3.html (2021).

Chinese State Council. The overall program of football reform and development. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-03/16/content_9537.htm (2015).

Liu, W. The realistic contradiction of the development of Chinese football undertaking and its reform path in the perspective of the requirements for deepening the system reform of the 19th National Congress Report. Journal of Guangzhou Sport University 38, 4–7 (2018).

Kipnis, A. B. Governing Educational Desire: Culture, Politics, and Schooling in China. (University of Chicago Press, 2019).

Storm, L. K. et al. Every Boy’s dream: A mixed method study of young professional Danish football player’s transnational migration. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 59, 102125 (2022).

FIFA. FlFA Talent Development - Give every talent achance. https://digitalhub.fifa.com/m/64a5d5908a12cabd/original/FIFA-Talent-Development-Give-every-talent-a-chance.pdf (2020).

Tojo, Ó., Spyrou, K., Teixeira, J., Pereira, P. & Brito, J. Effective Playing Time Affects Technical-Tactical and Physical Parameters in Football. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 5, (2023).

FIFA. Global Football. https://publications.fifa.com/en/talent-development/global-football/ (2020).

FIFA. The transition of talent. https://publications.fifa.com/en/talent-development/the-transition-of-talent/ (2020).

Fangcheng ASISI. Why must Japan ‘send out’ its players? https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzUxNDM1MDE3NA==&mid=2247551818&idx=1&sn=f4db5feb3b79a8a0e91fb5cb9d04ed5f (2022).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate FBref.com for providing authoritative and comprehensive data to football fans and researchers around the globe.

Funding

This study was supported by the ‘Research Project on the Exploration of Open and Cultivation Models for the Integration of Science and Education Platforms Aimed at Cultivating Top Innovative Talents’ from Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Grant No. 2024JGKJ009, and the ‘Research Project of Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education’, Grant No. 20YJC890032.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L. conceived and designed the study, collected materials, and conducted data analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by L.L., X.L., Y.T., G.S. and E.G. validated the data. H.X. provided supervision. L.L. and H.X. acquired funding for the research. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, L., Tang, Y., Li, X. et al. East Asian expatriate football players and national team success: Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean players in Europe (2000–2024). Sci Rep 15, 3707 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80953-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80953-7