Abstract

The diagnosis and treatment capability levels of healthcare professionals directly affect the overall quality of medical services. Enhancing these capability levels requires strengthening the professional skill training of healthcare workers, especially those in primary care settings in economically underdeveloped areas. To understand the actual needs for professional skill training among primary healthcare workers, thereby providing data support for targeted training initiatives. An online survey was conducted using convenience sampling and subsequently, snowball sampling from May 10, 2023 to January 31, 2024. The survey included 3811 healthcare workers across China, and 3617 valid questionnaires were recovered. Descriptive analysis was used to compare the professional backgrounds and training needs of healthcare workers at different medical facility levels. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to explore factors influencing the training of primary healthcare workers. The survey revealed that 70.1% of respondents were female, and 94.2% were from medical facilities below the provincial level, with 43.2% from township-level or lower medical facilities. Significant differences were found in age distribution, work experience, professional titles, educational levels, and training needs among provincial/national, prefectural/county, and township levels (P < 0.05). Busy clinical work schedules were the primary barrier to training participation. Most healthcare workers (78.7%) expected more than four training sessions per year, with the optimal frequency being quarterly. The most anticipated training topics among primary care workers were latest medical guidelines, new technologies/skills, and advanced management concepts, with over 80% interest. Compared with prefectural/county-level facilities, primary care workers at grassroots facilities are more significantly impacted by lower professional titles, lower education levels, weaker medical/technical skills, and insufficient specialized funding (odds ratio > 1, P < 0.001). Training should be tailored to the needs of healthcare workers at different medical facility levels. Particularly for primary care settings, providing special funding support and training in the latest medical guidelines, new technologies/skills, and advanced management concepts are important to improve the composition of titles, education, and professional technicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

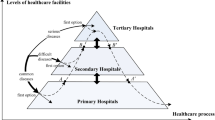

Primary healthcare services play an indispensable role in ensuring optimal public health and in directly impacting the quality of the overall medical service system, which constitutes an integral part of a comprehensive healthcare system1. The importance of primary care facilities, especially in meeting the growing public demand for quality medical services, has become increasingly prominent. In recent years, China’s healthcare system has undergone profound transformations and significant advancements2,3. The establishment of national/provincial regional medical centers and regional healthcare consortia has not only elevated medical technology and standards but has also enhanced the health status of the population4,5. However, these positive changes were initially concentrated in urban and economically developed areas4,6, leaving rural and less economically developed regions with severely limited medical resources.

County- and township-level primary care facilities carry the crucial task of bridging urban and rural medical resources and fulfilling the medical needs of both rural and urban residents7. The diagnostic and treatment capability level of healthcare workers directly influence the quality and efficiency of primary healthcare services8. Yet, primary care units face numerous challenges9, among which lack of professional skill training for healthcare personnel is a key concern10. Despite the series of supportive policies launched by the Chinese government to advance the development of primary care facilities11, the training needs of grassroots healthcare workers remain largely unmet.

To deeply understand the training needs of and main challenges faced by healthcare personnel in primary care units, this study conducted a nationwide electronic survey, collecting extensive data from healthcare workers in various regions and medical facility levels, particularly from economically underdeveloped rural areas of China. This study aimed to comprehensively assess the training needs of and issues faced by grassroots healthcare workers in economically disadvantaged areas to improve the quality of primary healthcare services, reduce the urban-rural healthcare disparity, and provide objective data support for the formulation of relevant policies and initiation of training programs.

Subjects and methods

Study subjects

The study population comprised Chinese healthcare workers. The inclusion criteria were (1) aged 18 years or older; (2) capable of independent decision-making; and (3) engagement in frontline clinical work in hospitals or clinics for at least six months. The exclusion criteria included (1) aged below 18 years; (2) non-frontline medical personnel; and (3) individuals with psychiatric disorders who cannot cooperate or is unwilling to participate.

Methods

Research design

This study utilized a cross-sectional survey design on a national scale. We developed an original survey titled “Strengthening Primary Care Medical Needs Questionnaire,” which included sections on personal demographics, previous training content/frequency, satisfaction with past training, current training needs, preferred training frequency, and anticipated future training topics and programs. To ensure that the survey design accurately reflects the needs of the target population, we conducted an extensive literature review and conducted field visits to several primary healthcare facilities to collect preliminary data. These preparatory efforts provided the basis for the targeted design of the questionnaire.

Healthcare facilities were categorized by administrative levels, including provinces, autonomous regions, municipalities, prefectures, counties, townships, communities, and villages. The focus was on the training needs of medical personnel at the county level/prefecture level and below, collectively referred to as primary healthcare facilities.

Survey design

The survey aimed to collect data on the training needs related to diagnostic and service enhancement skills of medical staff. It consisted of structured single and multiple-choice questions, rating/scale questions, and open-ended questions. Satisfaction was rated on a Likert scale from 1 (dissatisfied) to 5 (highly satisfied). To ensure the practicality of the survey, extensive literature review and field visits to primary healthcare units were conducted to gather preliminary data, which informed the targeted design of the survey.

Survey content

The questionnaire collected basic information such as gender, age, years of experience, professional title, and educational level. It also included sections on past training experiences (annual number of trainings, topics, and satisfaction), current training status (desired frequency, medical/technical skills, management, teaching/research needs, and preferences), and future training needs (most anticipated training topics such as clinical guidelines, new theories, technologies, methods, and teaching/research).

Survey evaluation

To ensure the practicality of the survey, we conducted preliminary survey preparation and an extensive literature review in early April 2023, prior to formal questionnaire distribution. In mid-April, we visited a remote township health center, where we delivered a training session on the latest version of “Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines Interpretation and Clinical Medication Guidance” to local primary healthcare workers. After the training, participants expressed a strong desire for such sessions to be held regularly. Through face-to-face interviews with healthcare staff, we gained an initial understanding of their urgent need for clinical skill enhancement. Two weeks later, we revisited the same township health center and provided a more in-depth and systematic interpretation of the latest clinical guidelines and practical skills training. Based on their feedback regarding training needs, we conducted a preliminary survey to assess their demand for training aimed at improving clinical competence. The questionnaire was subsequently refined, incorporating the results of this pre-survey, to better reflect the actual needs of primary healthcare workers.

Questionnaire validation

To assess the reliability of the questionnaire, a revised version was sent to participants who completed the pre-survey two weeks after the initial administration, along with a follow-up explanation. A total of 124 healthcare workers participated in the pre-survey. For the pilot study, a reliability test was conducted, with test-retest reliability coefficients (for demographic data) exceeding 0.865. The satisfaction ratings demonstrated strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.924 and a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of 0.836, indicating high reliability and validity of the questionnaire.

Sample size calculation

This study is a cross-sectional investigation aimed at estimating the demand for skill training among primary healthcare workers in China. Based on previous research and preliminary survey results, the rate of demand for training, which represents the proportion of primary healthcare workers estimated to express a need for skill training was anticipated to be 64%. A two-sided test was utilized with an alpha (α) of 0.05 and an allowable error margin of 0.02. Using PASS15.05 software(NCSS, LLC, Kaysville, UT, USA), the required sample size was calculated as N = 2261. Considering a non-response rate of 20%, at least 2827 participants had be included in the survey.

Data collection process

The survey was conducted from May 1, 2023 to January 31, 2024 using the “http://www.wjx.cn” platform. A convenience random sampling method was employed; to enhance the representativeness of the sample, we carefully considered different regions across China, including areas with varying levels of economic development, healthcare infrastructure, and medical needs. We selected medical facilities from Yunnan, Sichuan, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Shanxi, Hebei, Shandong, and Zhejiang provinces for this nationwide cross-sectional survey. All selected facilities were nationally certified healthcare institutions. Through collaboration with local authorities, associations, and individual healthcare workers, we primarily included healthcare professionals from the prefecture/county- levels and below, which are the most representative of primary healthcare in these regions.

Medical personnel were invited to participate in the survey, through multiple channels, including corporate WeChat, Tencent QQ, hospital/department WeChat groups, professional associations/societies, and on-site conference surveys using a snowball sampling approach. Additionally, invitations were sent through the nationally authenticated medical personnel learning and exchange platform “Doctor Circle” application to professional groups and individuals. Each smartphone/IP address was restricted to submitting only one questionnaire, and submission was allowed only after all questions are answered, all of which were mandatory.

Quality control of questionnaires

Before the survey, a thorough understanding of the basic situation of the selected units was established. Liaison officers familiar with the operations of their institutions conducted pre-survey publicity and explanations to ensure the respondents could answer questions without reservations. During the implementation, all participants were required to confirm their identity as healthcare professionals before the survey, and strict monitoring was performed to eliminate non-medical personnel’s questionnaires. After the responses were collected, two trained data verification officers reviewed all the questionnaires, discarding those with excessively short completion times, contradictory logical answers, incorrect information, or non-medical professional respondents. Stringent quality control measures and management were maintained throughout the project to ensure data reliability.

Data analysis methods

The cleaned data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0(IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).Descriptive statistical analysis was used to describe the basic characteristics of the participants, with frequency and percentage used to present categorical data and the χ2 test used for intergroup comparisons. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, Pearson’s coefficient, and the KMO test were employed to evaluate the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. Differences in training needs between county-/prefecture-level and township-level primary healthcare facilities were initially analyzed using univariate analysis (χ2 test), followed by multivariate logistic regression analysis to analyze factors with P < 0.25 to avoid prematurely excluding variables that may have weaker associations in the univariate analysis but could become significant in the multivariate analysis after adjusting for other factors (a less stringent P-value of < 0.25 is typically used in the initial stage). Further analysis was conducted to explore the main factors affecting training at the grassroots level. A significance level of α = 0.05 was used, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Basic characteristics of survey respondents

A total of 3811 healthcare workers nationwide submitted electronic questionnaires. After excluding 194 questionnaires due to excessively short completion times, contradictions in responses to logic questions, incorrect information, or non-healthcare professional status, 3617 valid questionnaires remained, yielding an effective response rate of 94.9%. Of the valid respondents, 2534 were female, accounting for 70.1% of the effective sample. According to medical facility level, county- or prefectural-level hospitals comprised 1846 respondents (51.0%); township health centers/health service centers had 875 respondents (24.2%); village health rooms/health service stations and clinics had 688 respondents (19.0%); and provincial/national-level medical institutions had 208 respondents (5.8%).

Preliminary analysis indicated significant differences across key indicators between staff at township-level and lower medical facilities and those at county/prefectural-level hospitals. Specifically, among township-level and below primary care units, only 22% (198 respondents) of the healthcare workers were aged 36 to 45 years; 23% (146 respondents) had 11 to 15 years work experience; 19% (193 respondents) held intermediate professional titles; 21% (605 respondents) were physicians, nurses, and medical technicians; and less than 19% (422 respondents) had a bachelor’s degree. In contrast, these indicators were significantly higher at county/prefectural-level hospitals, ranging from 49.5% to 65.2%. Notably, nearly 50% of the medical staff working in township health centers/health service centers and village health rooms/health service stations were non-physicians, nurses, or medical technicians, showing significant differences across the different levels of medical facilities. However, the differences between genders were not significant (Table 1).

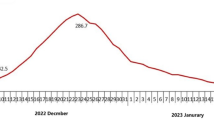

Comparative analysis of past training among healthcare personnel in different medical institution levels

Survey results revealed significant disparities in the frequency of skill/professional training received by healthcare personnel across various levels of medical institutions. In county/district-level hospitals, more than half (around 50%) of the healthcare personnel received training more frequently, significantly higher than those in township and lower-level grassroots medical units (less than one-fourth). Among them, 46.1% (1669/3617) of healthcare personnel received training opportunities ranging from 3 to 5 times or more annually. Conversely, about one-fourth (105/427) of grassroots healthcare personnel in health stations, health service centers, and clinics did not have any training opportunities in the past year (Fig. 1).

Regarding different professional titles, half (1948 out of 3617) of the healthcare personnel received training no more than twice annually. Personnel with lower professional titles (12.7%) or without titles (15.8%) had fewer training opportunities (Fig. 2). Regarding educational background, healthcare personnel with undergraduate degrees had the highest training opportunities (approximately 60%; 993 out of 1669); whereas only less than 10% (208 out of 3617) of grassroots healthcare personnel with vocational school or lower educational backgrounds received training opportunities ranging from 1 to 2 times annually (Fig. 3). Additionally, regarding age distribution, healthcare personnel who received training opportunities ranging from 1 to 2 times annually accounted for the highest proportion, exceeding 40% (1521 out of 3617). Less than 15% of healthcare personnel (427 out of 3617) received training less than once annually (Fig. 4).

Main barriers to healthcare workers’ skill training and desired ideal training frequency

The survey results indicated that the primary obstacle preventing healthcare workers from participating in skill training is the busy clinical workload, exacerbated by limited infrastructure in remote areas and a lack of opportunities for online learning. Specifically, 67.7% (2447 out of 3617) of the respondents reported that they lacked the time to attend training due to their demanding clinical schedules, while less than 1% expressed disinterest or refusal to participate in training. Additionally, 27.3% (986 out of 3617) of healthcare workers stated that they had no opportunity to engage in any skill training. Among those who indicated a lack of training opportunity, nearly half (467 out of 986) held junior professional titles (Fig. 5).

The preferred frequency for ideal training sessions among healthcare workers is quarterly (four times a year), with 40.3% (1457 out of 3617) of respondents endorsing this frequency. Approximately 40% (1389 out of 3617) of healthcare workers wish for unlimited training opportunities annually. This preference is particularly prominent among those working in county-level or higher medical institutions, comprising over 54% (751 out of 1389) of this subgroup. In contrast, in township-level and lower grassroots medical units, 40.7% (565 out of 1389) of the respondents expressed a desire for unlimited training opportunities annually (Fig. 6).

Specific training programs and needs

The results indicated that over 80% of healthcare workers expressed the highest anticipation for specific training content, including new clinical guidelines (2163 out of 3617), emerging skills/technologies (1942 out of 3617), and advanced management concept applications (2094 out of 3617). Furthermore, the most sought-after assistance from medical consortia/expert workstations/partnering experts includes the implementation of new technologies/projects, acquisition of talent, and enhancement of teaching and research capabilities (see Figs. 7 and 8).

Analysis of disparities in major training needs among medical personnel in different levels of medical institutions

The results indicated no significant differences in the training needs of medical personnel from different medical institution levels regarding obtaining the latest clinical guidelines for clinical work and expecting excellent management concepts provided by medical alliances/expert workstations/supporting experts (χ2=0.795, P = 0.851; χ2=7.389, P = 0.060). However, significant differences were observed in the training needs for acquiring new concepts/technologies, improving medical skills/technologies/management abilities, adopting new methods to enhance work efficiency, and enhancing research/teaching abilities among medical personnel from different levels of medical institutions (P < 0.001 for all). Medical personnel from county/district-level hospitals showed the strongest demands, especially for support provided by medical alliances/expert workstations/supporting experts, including the implementation of new technologies/projects, introduction of outstanding talents, support for special funds, and enhancement of teaching/research abilities (see Table 2).

Factors influencing the enhancement of operational capabilities in township-level and below primary healthcare units (multifactor analysis)

County/city-level hospitals offer more training opportunities compared with that offered by township-level and below healthcare units (township health centers + health stations/clinics). However, a significant deficiency in training was observed in township-level and below healthcare units. To clarify the primary factors influencing the enhancement of operational capabilities in township-level and below primary healthcare units, a logistic multifactor regression analysis method was employed. County/city-level hospitals were considered as the reference independent variable (x = 0), while township health centers/health stations/clinics were considered as “x = 1,” to explore the related factors affecting the improvement of operational capabilities in township-level and below primary healthcare units. Based on the univariate analysis, factors with P < 0.25 were included in the logistic multifactor regression analysis to analyze the primary factors influencing training in township-level and below primary healthcare units.

The results indicated that compared with county/city-level hospitals, the proportion of personnel without professional titles and with primary professional titles in township-level and below healthcare units was significantly higher than that in county/city-level hospitals (OR = 9.7, 95% CI 6.3–14.7; OR = 3.0, 95% CI 2.3–3.8). At the educational level, the proportion of personnel with secondary education or below was higher in primary healthcare units (OR = 31.4, 95% CI 7.7–128.8) than in other facility levels. Additionally, the lack of medical technology/skills/management capabilities (OR = 1.5, 95% CI 1.2–1.9) and the need for special fund support (OR = 1.4, 95% CI 1.2–1.7) were closely related to the enhancement of operational capabilities in primary healthcare personnel, showing statistical significance (P < 0.001). In contrast, healthcare personnel in county-/city-level hospitals have a greater advantage of enhanced operational capabilities, with higher proportions of personnel holding advanced professional titles, possessing bachelor’s degrees or above, mastering new skills/technologies, and having expertise in research/teaching (OR < 1, P < 0.005) (see Table 3).

Discussion

China’s healthcare reform has made significant progress in the allocation of medical resources12, personnel organization management, resource coordination and allocation, incentive policies for medical staff, and the co-construction and sharing of medical information. However, these achievements are primarily concentrated in tertiary medical institutions in developed regions and at the provincial and prefectural levels13. Compared with the thousands of counties and township-level grassroots medical units, the improvement of diagnosis and treatment capability levels and service quality remains a major challenge for healthcare reformation14.

In the context of China’s framework for high-quality and sustainable development15, this study conducted a nationwide questionnaire survey focusing on the training needs of grassroots medical staff in enhancing operational capabilities. This research primarily targeted economically underdeveloped prefectural-/county (city)-level and below grassroots medical units, especially the medical staff of township health centers and clinics. We explored several key factors influencing medical staff training for improving grassroots medical services and analyzed the relevant factors, proposing corresponding suggestions and countermeasures as follows:

(1) Training needs and improvement recommendations

Grassroots medical staff demonstrated a high demand for training in enhancing operational capabilities. This study shows that 78.7% of respondents expected to receive skill training four or more times a year, with this demand being significantly higher in county (city)-/prefectural-level hospitals than in township-level and below grassroot medical units. Both exhibit significant differences in the composition of professional technical personnel, work experience, age distribution, and distribution and composition of professional technical titles. The disadvantages of the latter, particularly the issue of the training of staff with lower professional titles and education levels, are more pronounced. Unfair training opportunities and training deficiencies directly impact the breadth and depth of grassroots medical services16, with the professional competence of medical staff directly affecting the quality and efficiency of medical services. This necessity for enhanced training among grassroots medical personnel has also been underscored by findings in related studies17.

Therefore, providing sufficient, equitable, and targeted training programs that meet the actual needs of grassroots medical units is not only key to improving the level of medical services but also an important means to optimizing the allocation of medical resources and enhancing the accessibility and equity of medical services18. This requires not only active intervention and support from governments and relevant institutions19 but also extensive cooperation and consensus from within and outside the medical community. Faced with this challenge, the following measures are recommended to improve the existing medical training system. (1) Policy support: Governments should enact more robust policies to ensure that grassroots medical staff receive regular systematic professional training18,20; (2) Redistribution of resources: Resource allocation should be optimized to ensure fairness of training opportunities, especially in underdeveloped medical conditions at grassroots levels below townships; and (3) Diversification of training content: Training content should be expanded to cover not only professional skills but also non-technical skills such as medical ethics and patient communication.

(2) Barriers to training participation and strategies to address them

Busy clinical work is the primary barrier to training opportunities for medical staff in grassroots medical units. This finding is consistent with the results of Liu et al.21, which similarly identified work pressure as a core factor hindering medical staff participation in continuing.

education. Heavy workloads do not only limit the time and energy medical staff can dedicate to training but may also diminish their willingness to participate in training. Our survey found that differences in professional titles and education significantly influence medical staff’s training participation, preferences for training content, and modes. For example, medical staff with higher education levels or professional titles may lean towards in-depth updates on professional knowledge or enhancement of management skills, while those with grassroots or junior titles may require reinforcement of basic knowledge and skills22, particularly with high demand for the latest clinical guidelines, new technologies, and skills. In addition to weak grassroots medical technology, insufficient infrastructure, and a lack of online learning opportunities in remote areas, a severe shortage of professionals is the primary reason for the lack of training among medical staff, particularly evident in grassroots medical institutions below the township level. The low proportion of professionals such as doctors/nurses is the main influencing factor, leading to severe lack of training opportunities for medical staff due to their heavy clinical workloads23. Therefore, when designing training programs, these differences should be fully considered to ensure the relevance and practicality of the training content. Planned, batched, and targeted training content can enhance the effectiveness and attractiveness of training.

In response to identified barriers to training participation, this study proposes the following strategies and recommendations to promote widespread participation in training among medical staff. (1) Alleviating Workloads: Implement workload management measures, such as scheduling work hours and shift systems reasonably24 to provide medical staff with more time and space to participate in training; (2) Increasing Training Opportunities: Develop and provide customized training programs, especially online training and flexible learning modes25, for medical staff with different professional titles and educational backgrounds to accommodate their diverse needs; and (3) Interdepartmental Collaboration: Establish mechanisms for multi-departmental collaboration between medical, educational26, and financial departments to jointly support medical staff training27. For example, the education sector can be responsible for developing training content and compiling teaching materials, the finance department can provide funding support for training projects28, and medical institutions can be responsible for implementing training and evaluating effectiveness.

By identifying and addressing barriers to medical staff participation in training, we can improve the coverage and effectiveness of training, thereby enhancing the quality and efficiency of the entire healthcare industry. This requires policymakers, education providers, and medical institutions to take practical measures29, including optimizing working conditions, expanding training opportunities, and utilizing technological innovations to promote equal access to educational resources.

(3) Optimization of training content and implementation strategies

Under the current trends in medical development, medical staff face the challenge of continually updating their knowledge and skill sets30. This study emphasizes the urgent need for medical staff to acquire knowledge on the latest diagnosis and treatment guidelines, new skills, and technologies in their field. This reflects the universal requirement of the healthcare industry for continuous learning and adaptation to new developments while highlighting that existing training systems need to be continuously updated to meet the demands of best medical practices31. The study also found that besides clinical skills, training needs regarding management concepts and teaching/research abilities for medical staff are equally important27,32, indicating that the role of the medical staff had expanded from being solely clinical service providers to comprehensive medical professionals requiring management, teaching, and research capabilities29,33. Therefore, the optimization of training content should include the latest medical knowledge and technologies, as well as enhanced management abilities, teaching methods, and research skills.

To effectively meet these diverse training needs, the following strategies are crucial. (1) Diversified Training Content: Design and implement a comprehensive training program34 that includes the latest medical knowledge and technologies, as well as management skills, educational skills, and research methods. For grassroots medical personnel, emphasis should be placed on enhancing their clinical skills and ability to respond to public health emergencies35. For those with higher professional titles or education levels, advanced courses in management, research, and teaching can be added; (2) Flexible Training Methods: Given the busy clinical work pressure on medical staff, training programs should provide flexible learning methods, such as online learning, remote meetings, short-term intensive training, and refresher courses36. Meanwhile, by utilizing modern information technological means such as mobile learning applications and online discussion platforms, the interactivity and attractiveness of training can be increased to meet different learning styles and needs; and (3) Strengthening Practice and Feedback: To ensure the effectiveness of training, theoretical learning should be combined with practical operations, providing ample opportunities for practice and personalized feedback37. Through methods such as simulation practice, clinical rotations, and project implementation, medical staff can deepen their understanding and application of new knowledge and skills38; and (4) Continuous Career Development Support: Considering the importance of professional promotion and continuing education in the career development of medical staff, measures should be taken to encourage lifelong learning, such as providing academic advancement opportunities, establishing online learning platforms, and introducing a continuing educational credit system39.

Limitations

Although this study utilized a nationwide cross-sectional survey and made efforts to enhance sample representativeness, the convenience sampling method may limit its randomness in certain aspects, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings. Future research could adopt more rigorous random sampling methods to improve the scientific validity and representativeness of the results. Additionally, this study did not conduct a long-term follow-up on the training programs, limiting our ability to assess their lasting impact on healthcare workers’ skill enhancement and clinical outcomes. Future research should consider longitudinal analyses to explore the relationship between training interventions and clinical outcomes. Moreover, the potential influence of gender and other diverse factors on training needs was not examined in detail in this study, warranting further investigation to better inform training policies and program design.

Conclusion

This study conducted a comprehensive analysis of the training needs and current status of public health service personnel in grassroots medical units in China, revealing barriers to training participation and potential directions for optimizing training content. However, the cross-sectional nature of the data presents limitations, as this study could not assess the long-term impact of training on healthcare workers’ skill development and clinical outcomes. The study results are of great significance for optimizing public health training policies and improving the quality of grassroots medical services. Through targeted strategies and policy recommendations, the service capacity of medical staff can be effectively enhanced, thereby improving the overall level of public health services.

Data availability

Due to privacy and identifiable information concerns related to participants, the datasets generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available. However, they can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Frieden, T. R., Lee, C. T., Lamorde, M., Nielsen, M. & McClelland, A. The road to achieving epidemic-ready primary health care. Lancet Public Health 8(5), e383–e390. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00060-9 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Horizontal inequity trends of health care utilization in rural China after the medicine and healthcare system reform: based on longitudinal data from 2010 to 2018. Int. J. Equity Health 22(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-023-01908-4 (2023).

Cai, C., Hone, T. & Millett, C. The heterogeneous effects of China’s hierarchical medical system reforms on health service utilisation and health outcomes among elderly populations: a longitudinal quasi-experimental study. Lancet (London England) 402(Suppl 1), S30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02141-4 (2023).

Fu, J. et al. National and Provincial-Level Prevalence and Risk factors of carotid atherosclerosis in Chinese adults. JAMA Netw. Open 7(1), e2351225. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.51225 (2024).

Fu, X., Wang, X., Huang, Y. Li, R. Exploration on the Construction Mode of National Traditional Chinese Medicine Regional Medical Center: a case study of Dongzhimen Hospital of Beijing University of Chinese Medicine. Chin. Health Qual. Manag. 11, 7–10. https://doi.org/10.13912/j.cnki.chqm.2023.30.11.02 (2023).

Ju, W. et al. Cancer statistics in Chinese older people, 2022: current burden, time trends, and comparisons with the US, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. Sci. China Life Sci. 66(5), 1079–1091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-022-2218-x (2023).

Özkaytan, Y., Schulz-Nieswandt, F. & Zank, S. Acute health care provision in rural long-term care facilities: a scoping review of integrated care models. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 24(10), 1447–1457e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2023.06.013 (2023).

Coombs, C. et al. Primary care micro-teams: an international systematic review of patient and healthcare professional perspectives. Br. J. Gen. Pract. J. R. Coll. Gen. Pract. 73(734), e651–e658. https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2022.0545 (2023).

Russo, G., Perelman, J., Zapata, T. & Šantrić-Milićević, M. The layered crisis of the primary care medical workforce in the European region: what evidence do we need to identify causes and solutions? Hum. Resour. Health 21(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-023-00842-4 (2023).

Ramšak, M. et al. Diversity awareness, diversity competency and access to healthcare for minority groups: perspectives of healthcare professionals in Croatia, Germany, Poland, and Slovenia. Front. Public Health 11, 1204854. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1204854 (2023).

National Health Commission Website. Press Conference Transcript of the National Health Commission on March 27. Propaganda Department. Retrieved on April 3, 2024. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/s3574/202403/023cc0c823c64c2d99f73981578be07f.shtml (2024).

Yip, W. et al. Universal health coverage in China part 2: addressing challenges and recommendations. Lancet Public Health 8(12), e1035–e1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00255-4 (2023).

Chen, W., Ma, Y. & Yu, C. Unmet chronic care needs and insufficient nurse staffing to achieve universal health coverage in China: analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 144, 104520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2023.104520 (2023).

Yang, X., Chen, Y., Li, C. & Hao, M. Effects of medical consortium policy on health services: an interrupted time-series analysis in Sanming, China. Front. Public Health 12, 1322949. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1322949 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Current situation and needs analysis of medical staff first aid ability in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Emerg. Med. 23(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-023-00891-x (2023).

Baum, N. M., Iovan, S. & Udow-Phillips, M. Strengthening public health through primary care and public health collaboration: innovative state approaches. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. JPHMP 30(2), E47–E53. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001860 (2024).

Endalamaw, A. et al. Barriers and strategies for primary health care workforce development: synthesis of evidence. BMC Prim. Care 25(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02336-1 (2024).

Shahnazi, H. et al. L a quasi-experimental study to improve health service quality: implementing communication and self-efficacy skills training to primary healthcare workers in two counties in Iran. BMC Med. Educ. 21(1), 369. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02796-4 (2021).

Wakida, E. K. et al. Health system constraints in integrating mental health services into primary healthcare in rural Uganda: perspectives of primary care providers. Int. J. Mental Health Syst. 13, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0272-0 (2019).

Krishnamoorthy, Y. et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing the national patient safety implementation framework in public health facilities in Tamil Nadu: a qualitative study. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 11(6), e2200564. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-22-00564 (2023).

Liu, J. & Mao, Y. Continuing medical education and work commitment among rural healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in 11 western provinces in China. BMJ Open 10(8), e037985. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037985 (2020).

Simons, M. et al. Integrating training in evidence-based medicine and shared decision-making: a qualitative study of junior doctors and consultants. BMC Med. Educ. 24(1), 418. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05409-y (2024).

Hinzmann, D., Haneveld, J., Heininger, S. K. & Spitznagel, N. Is it time to rethink education and training? Learning how to perform under pressure: an observational study. Medicine 101(52), e32302. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000032302 (2022).

Belingheri, M., Paladino, M. E. & Riva, M. A. Working schedule, sleep quality, and susceptibility to coronavirus disease 2019 in healthcare workers. Clin. Infect. Dis. 72(9), 1676. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa499 (2021).

Latchem-Hastings, J., Latchem-Hastings, G. & Kitzinger, J. Caring for people with severe brain injuries: improving health care professional communication and practice through online learning. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 43(4), 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000486 (2023).

Cathcart, L. A. et al. An efficient model for designing medical countermeasure just-in-time training during public health emergencies. Am. J. Public Health 108(S3), S212–S214. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304599 (2018).

Timofeiov-Tudose, I. G. & Măirean, C. Workplace humour, compassion, and professional quality of life among medical staff. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 14(1), 2158533. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2022.2158533 (2023).

Alnahhal, K. I. et al. Comparison of academic productivity and funding support between United States and international medical graduate vascular surgeons. J. Vasc. Surg. 77(5), 1513–1521e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2022.12.038 (2023).

Louizou, E., Panagiotou, N., Dafli, E., Smyrnakis, E. & Bamidis, P. D. Medical doctors approaches and understanding of health literacy: a systematic literature. Rev. Cureus 16(1), e51448. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.51448 (2024).

McKerrow, I., Carney, P. A., Caretta-Weyer, H., Furnari, M. & Miller Juve, A. Trends in medical students’ stress, physical, and emotional health throughout training. Med. Educ. Online. 25(1), 1709278. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2019.1709278 (2020).

Magen, E. & DeLisser, H. M. Best practices in relational skills training for medical trainees and providers: an essential element of addressing adverse childhood experiences and promoting resilience. Acad. Pediatr. 17(7S), S102–S107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.03.006 (2017).

Boerebach, B. C., Lombarts, K. M. & Arah, O. A. Confirmatory factor analysis of the System for Evaluation of Teaching Qualities (SETQ) in graduate medical training. Eval. Health Prof. 39(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278714552520 (2016).

Brown-Johnson, C. et al. Qualitative interview study of strategies to support healthcare personnel mental health through an occupational health lens. BMJ Open 14(1), e075920. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-075920 (2024).

Triola, M. M. & Burk-Rafel, J. Precision medical education. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll.. 98(7), 775–781. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000005227 (2023).

Hoffman, J. L., Wu, T. Y. & Argeros, G. An innovative community health nursing virtual reality experience: a mixed methods study. Creat. Nurs. 29(3), 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/10784535231211700 (2023).

Sadek, O., Baldwin, F., Gray, R., Khayyat, N. & Fotis, T. Impact of virtual and augmented reality on quality of medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 15(3), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-22-00594.1 (2023).

Faria, I. et al. Online medical education: a student survey. Clin. Teach. 20(4), e13582. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13582 (2023).

Gasim, M. S., Ibrahim, M. H., Abushama, W. A., Hamed, I. M. & Ali, I. A. Medical students’ perceptions towards implementing case-based learning in the clinical teaching and clerkship training. BMC Med. Educ. 24(1), 200. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05183-x (2024).

Reynolds, A. K. Academic coaching for learners in medical education: twelve tips for the learning specialist. Med. Teach. 42(6), 616–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1607271 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the healthcare professionals who participated in this study. Special thanks are due to Ms. Yan Luan from the Department of Medical Education and Ms. Yufen Xiao from the Department of Electrocardiography at The Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, as well as to Mr. Hongwei Wang from the People’s Hospital of Xiangyun County, Dali, Yunnan Province, Ms. Wen Li from the School of Public Health, Nanjing Medical University, Ms. Yi Li from the Affiliated Hospital of Hebei University, Ms. Jia Liu from Wuqiao County Hospital of Hebei Cangzhou City, and Ms. Jianglan Li from the Red Star Hospital of the 13th Division of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, for their valuable support in conducting the questionnaire survey.

Funding

This work was supported by the Public Hospital High-Quality Development Scientific Research Public Welfare Fund Project Fund (2023) of the China Health Promotion Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bin Liu and Min Zhang were responsible for project proposal, organization, and drafting of the manuscript. Qiang Xue, Jianwei Sun, Xiangang Li, and Zhenyi Rao were responsible for project implementation quality control and inter-unit communication. Guangying Zou, Xin Li, Zhaoyuan Yin, Xianyu Zhang, and Yahua Tian assisted with participant recruitment. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study strictly followed the Declaration of Helsinki formulated by the World Medical Association and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Gejiu People’s Hospital (Approval Number: 2023YNLL01). Study participation was accepted after informed consent was signed. Study participants signed informed consent before taking the questionnaire.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, B., Xue, Q., Li, X. et al. Improving primary healthcare quality in China through training needs analysis. Sci Rep 14, 30146 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81619-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81619-0