Abstract

Cervical cancer (CC) ranks as the second highest cause of morbidity and mortality among young women; however, there are currently no age-specific definitions for young cervical cancer or prognostic models tailored to this demographic. Data on CC diagnosed between 2000 and 2019 were extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Age stratification is based on the relationship between age and cancer-specific mortality, as demonstrated by restricted cubic spline analyses (RCS). Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were employed to identify independent prognostic factors in the young CC group. Two novel nomograms for this population were developed and validated using an external validation cohort obtained from a local hospital database, evaluated with concordance index (C-index) and calibration plots. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were utilized to compare the accuracy of the established models against the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system (2018). A total of 27,658 patients from the SEER database were classified into three age groups (<36 years, 36-60 years, >60 years) based on RCS analyses, with 4,990, 16,922, and 5,746 patients in each group, respectively. The independent prognostic factors identified for young CC included stage, tumour size, grade, histologic type, and surgical intervention. The results of the C-index and calibration in both the training and validation sets confirmed that the two nomograms can accurately predict the occurrence and prognosis of young CC patients. The area under the curve (AUC) values indicated that these models demonstrated higher efficacy in predicting overall survival (OS) compared to the FIGO staging system (2018). These models could potentially serve as effective tools for clinicians to estimate the prognosis of young CC patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer death in women, with an estimated 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths worldwide in 2020, which represents a major global health challenge1. Boosting rates of HPV vaccination and effective screening have reduced the incidence of CC, and the World Health Organization (WHO) is committed to eradicating cervical cancer by achieving an incidence rate of no more than 4 cases per 100 000 women-years worldwide2. However, in adolescents and young women, CC remains the malignancy with the second highest morbidity and fatality rate3,4; moreover, increases in the incidence or mortality of CC among young women have been reported in some regions, such as urban China, Japan, Eastern European countries and Latin America5,6,7,8,9,10.

Adolescents and young women represent a distinct demographic in cancer research. Previous studies11,12,13,14 on young cervical cancer have encompassed a range of ages from 25 to 45 years, leading to a lack of consensus on the definition of young cervical cancer. Additionally, previous studies posited that young cervical cancer were involved in more aggressive pathogenesis, resulting in a poorer prognosis15,16,17; thus, youth was recognized as a prognostic factor for cervical cancer. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is currently a limited number of studies providing reliable data on the clinicopathological features and prognostic factors associated with young CC, and no predictive model for its prognosis has been established to date. In this study, we performed age stratification by a novel method and conducted this retrospective study to analyse the clinicopathological characteristics, treatments, and prognosis of young cervical cancer patients. We established visual prognostic models as a supplement to International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging to better predict the prognosis of young CC patients, which has not been studied before.

Methods

Database and participants

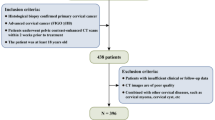

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (https://seer.cancer.gov/) is a US population-based cancer registry database. We used SEER*Stat software (version 8.4.1) to extract information on patients diagnosed with cervical cancer between 2000 and 2019. The primary topographic site was selected using ICD codes for Endocervix (C53.0), Exocervix (C53.1), Overlapping lesions of cervix uteri (C53.8) and Cervix uteri (C53.9). The data used for external validation were obtained from the Gynaecological database of the Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital, and information on patients with cervical cancer diagnosed between 2014 and 2020 was extracted. Inclusion was based on the following: first diagnosis of cervical cancer with primary focus and diagnosis confirmed by histopathology. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) survival time < 1 month and (2) missing data for the chosen variables.

Variables

Risk factors used for the analysis included age, marital status at diagnosis, median household income (inflation-adjusted), months from diagnosis to treatment, grade, histologic type (squamous, adenocarcinomas, and others including uncommon subtypes such as complex epithelial neoplasms, small cell carcinoma and adenosquamous cell carcinoma), tumour size (< 2 cm, 2–4 cm, > 4 cm), stage, surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Since 2018, the pathological grading of tumours reported in the SEER database has been in accordance with a 3-category classification system, meaning that grade 4 (undifferentiated; anaplastic) was combined with grade 3 (poorly differentiated). To ease the interpretation of the results, we converted all data before 2018 into the 3-stage system. Besides, the FIGO staging system of cervical cancer was changed after 2018, mainly to include stage III lymph node metastasis. To reflect the role of lymph node metastasis in the prognosis of cervical cancer and be convenient for gynaecological clinical application, cases included were converted to 2018 FIGO stage (I, II, III, IV) in our study according to the SEER TNM staging data [AJCC 3rd (1988–2003) TNM data; Derived AJCC TNM stage, 6th edition (2004–2015); Derived SEER Combined TNM stage (2016–2017); Derived EOD 2018 TNM stage (2018+)]. In addition, according to the reported median annual household income in the United States in a previous study, $60,000 was set as the cut-off value to group the patients18.

Outcomes of interest

Overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) were set as outcomes. OS was defined as the period from the date of diagnosis until death attributed to any cause or to the end of follow-up. CSS was defined as the interval from the date of diagnosis until death as a result of cervical cancer or to the end of follow-up.

Statistical analysis

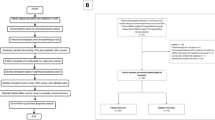

Continuous data are presented as medians and ranges, and categorical data are shown as frequencies and proportions. The Kaplan‒Meier method in X-tile software (Version 3.6.1, http://tissuearray.org) was used to evaluate the optimal cut-off value for months from diagnosis to treatment (Supplement 1). The relationship of age and the cancer-specific mortality of CC was fit by univariate Cox regression with restricted cubic spline (RCS) analyses (knot = 5)19. The cut-off values were set for age stratification in CC patients based on the inflection points in RCS. OS and CSS of different age groups were estimated using the Kaplan‒Meier method. Univariate Cox regression analysis was used to calculate the risk ratio (hazard ratio, HR) and the associated 95% confidence interval (CI) to screen potential prognostic factors affecting the OS and CSS of young CC patients from the SEER database; variables with statistically significant differences (p value < 0.05) were included in the multivariate Cox regression model to screen for independent risk factors (p value < 0.01) for prognosis in young CC patients. A nomogram model was constructed based on the results of the multivariate Cox regression analysis and assessed using the external validation cohort. The predictive ability of the model for death was assessed by the concordance index (C-index), and a higher C-index indicates a better ability to separate patients with different survival outcomes. The slopes of the calibration curves were used to compare the predicted probability with the observed probability in the study cohort. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) was used to compare the difference in the prediction accuracy between the model and the FIGO staging system (2018). All analyses were performed using R software, version 4.2.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing).

Ethical statement

We obtained signed authorization and permission to access and use the data from the SEER database and followed the protocol throughout the process to protect patient privacy. Furthermore, we retrospectively collected data from medical record system of Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital, and all patients’ personal information was anonymized, so the ethical review board of Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital approved the ethical requirements for this study and waived the requirement of obtaining written informed consent from patients. This study was conducted in accordance with the revised Declaration of Helsinki.

Result

Age-stratified incidence and outcomes of CC

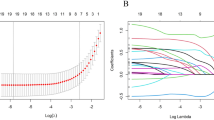

A total of 27,658 cases of cervical cancer from the SEER database were first enrolled in our study based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Supplement 2). The RCS presented a nonlinear relationship between age and cervical cancer-specific mortality (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). The plot showed a reduction trend of risk within the lower age range; the lowest risk was reached at age 35.58 years old [HR = 0.687, 95% CI (0.631, 0.749)], and then risk increased thereafter with a substantial increase after 60 years old. Based on these results, 36 and 60 years were set as the cut-off values for age stratification in our study. The KM curves (Fig. 2) present the OS and CSS of cervical cancer patients in three different age groups (< 36, 36–60, > 60). Patients in the young group had the best prognosis, followed by those in the middle-aged group, and the 5-year OS and CSS in both groups were over 70%. Undoubtedly, patients in the elderly group had the worst prognosis (P < 0.001), with a 5-year OS rate of approximately 50%. After 5 years of cervical cancer diagnosis and treatment, the CSS KM curve of all groups tended to be flat, which also verified the regularity of disease progression and confirmed the necessity of a standardized follow-up visit.

The relationship of age and the cancer specific mortality of CC fit by univariate Cox regression with RCS analyses. The Cox regression indicated a nonlinear relationship between age and the risk of death(p < 0.001), with the lowest risk of mortality at age = 35.58 years. When the age was older than 35.58 years, HR was positively correlated with age, whereas negative correlations between age and HR were identified when age was less than 35.58 years. When age was older than 60 years, the risk of death increased substantial with increasing age. Shaded areas represent 95% CI.

Baseline characteristics of young group patients and differences from the other two groups

4,990 cervical cancer patients (18.0%) younger than 36 years old were assigned to young group. In terms of demographic characteristics, nearly half of the young patients were never married (44.4%), and the proportion of patients with a relatively lower median household income (<$60,000) in this group was higher than that in the other groups (29.9% vs. 28.7% vs. 27.3%). Those patients exhibited a high compliance with treatment after diagnosis, with a higher proportion accepting treatment within 1 month (42.6% vs. 38.6% vs. 31.6%).

Regarding the clinical characteristics, in the young group, the proportion of other histologic types (nonsquamous cell neoplasms and nonadenocarcinoma) was higher than that in the other two groups (8.3% vs. 7.2% vs. 7.5%). The percentages of early-stage (FIGO stage I), grade 1 and smaller tumour sizes (< 2 cm) were higher than those of the other two groups (62.3% vs. 52.3% vs. 38.6%, 16.6%vs. 14.9%vs. 9.4%, 39.3% vs. 29.8% vs. 20.1%, respectively). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the different groups are summarized in Table 1.

Prognostic factors for young cervical cancer patients

The young age group was used as a training cohort for developing prognostic models for young, early-onset cervical cancer. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were successively performed to identify significant risk factors in the training cohort (Table 2; Fig. 3). Pathologic type, FIGO stage, tumour size and surgery were included in the final regression models. According to the multivariate Cox regression analysis results of OS, the grade did not meet the qualification of p < 0.01, but as a recognized prognostic factor, it was also incorporated into the final model. In addition, chemotherapy and radiotherapy status were significant high-risk factors with p < 0.01 but were not included in either model because patients who received chemotherapy or radiotherapy were also worse in tumour stage or grade, which might lead to logical errors or issues of multicollinearity in the models.

Visualization and validation of the prognostic models

Nomograms for OS and CSS respectively were presented for visualization of the prognostic models (Fig. 4). Apparently, stage had the greatest effect on prognosis, followed by tumour size. Contrary to common understanding, squamous carcinoma was associated with a worse prognosis than adenocarcinoma, and both were better than other types (nonsquamous cell neoplasm and nonadeocarcinoma). The C-indexes of the OS and CSS prognosis were 0.805 (95% CI: 0.793–0.817) and 0.820 (95% CI: 0.808–0.832), respectively.

A total of 125 patients from the gynaecological database of Guizhou Provincial People’s Hospital were included as the validation cohort in our study based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The demographic and clinical characteristics of this cohort were presented in Table S1. In the validation cohort, since all patients died from cervical cancer, we studied OS only, and the C-index was 0.865 (95% CI: 0.800–0.930).

In addition, the calibration plots of the training cohort and validation cohort showed a high fit between the nomogram-predicted survival and actual survival in terms of the probability of 3- and 5-year OS and CSS (Fig. 5).

Comparison of the nomogram with the FIGO staging system

The ROC curve was used to compare the accuracy between the established model and the FIGO staging system (2018). We plotted the ROC curves for the 3- and 5-year OS in the external validation cohort and calculated the AUC values (Fig. 6). The results showed that our model had higher efficacy in predicting OS than the FIGO staging system (2018).

Discussion

At present, the prognostic models of cervical cancer are gradually refined into special pathological subtypes, stage or disease status (such as lymph node metastasis) and special populations, and the accuracy of the models is excellent11,20,21. A prognostic model for young, early-onset cervical cancer has not been reported. The question is how to define ‘young’ patients. Previous reports have studied patients aged 25 years or younger as a very young group because the clinicopathological characteristics and pathogenesis of this population may be different from those of adult women over 25 years old12,13. There are also studies setting younger patients as under 30, 35 or 40 years with no explanation14. The results regarding the relationship between age and mortality in cervical cancer were inconsistent in studies with different samples, which may also point to a special relationship between age and prognosis. In this study, we applied a novel method to define the young group and performed age stratification for cervical cancer. RCS models have been proven to be a good tool to fit the nonlinear association between continuous variables and outcomes, and it has been confirmed that RCS, together with the Cox proportional hazards regression model, enables visualization of the shapes of dose‒response associations between a continuous variable and outcome risks22,23. The RCS plot presented a nonlinear relationship between age and mortality of CC patients in our study. Age of 36 and 60 were the inflection points in the plot; thus, it was reasonable to divide patients into 3 age groups based on these two cut-off values, and patients less than 36 years old were assigned to the young group.

Previous studies suggested that younger age was associated with a worse prognosis16,17. However, our findings indicate that the younger group exhibited the best prognosis, characterized by a higher proportion of early tumor stages, smaller tumor sizes, grade 1 tumors, and better medical compliance. Some other studies have reached similar conclusions12,14,24,25. Regarding prognostic factors, histologic type is widely acknowledged as significant in tumours. Ruiz et al. suggested that histology substantially affected OS of CC24. Certain pathological subtypes of CC exhibit more aggressive behavior and are not associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. HPV-negative CC was considered to be associated with a poorer prognosis26,27, and the sensitivity of cytological screening for these subtypes was lower than that for cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC)28, potentially resulting in delays in diagnosis. In our study, the proportions of nonsquamous cell neoplasms and nonadenocarcinoma types were higher in the young group but still less than 10% (8.4%), which may have had little impact on the overall prognosis. Similarly, in other studies of cervical cancer in young patients, no significant relation was found between histological type and survival12,25. In addition, the increasing incidence of young cervical cancer patients may be related to social factors. In this study, the proportion of single (never married) people in the young group was significantly higher than that in the other two groups, with a narrow gap in median household income compared to the middle age group. Being single and more likely to have multiple sexual partners29, promotes persistent HPV infection.

The prognostic model illustrated by the visualized nomogram has been employed in clinical research across various tumours30,31,32, including studies on cervical cancer33,34. In this study, nomograms were utilized to develop a prognostic model specifically for young cervical cancer patients. The independent prognostic factors identified included stage, tumour size, grade, histologic type, and surgical intervention, consistent with the findings of previous studies35,36. The relative weight of each prognostic factor was visually represented in the nomograms, demonstrating that each young cervical cancer patient with available clinical data on these prognostic factors could derive a specific score from the nomograms. This score could subsequently be utilized to predict 3- year or 5- year survival outcomes. Evaluation metrics for model accuracy included the C-index and the calibration curve, among others. We utilized the SEER database and incorporated statistically significant prognostic factors to develop a clinical prognostic model specifically for young cervical cancer patients, which has not been previously reported. The C-index for the OS model and the CSS model for young cervical cancer patients was 0.805 (95% CI: 0.793–0.817) and 0.820 (95% CI: 0.808–0.832), respectively. These values are higher than those reported for cervical cancer prognostic models in other studies37,38. In the validation set, the C-index reached 0.865 (95% CI: 0.800–0.930), confirming the good predictive ability of the nomograms. The calibration plots showed a high fit between the nomogram-predicted survival and actual survival, also providing proof for the robust clinical value of the nomograms.

The FIGO staging system has been updated to the 2018 version, which has been shown to provide better predictions of disease-free survival and OS compared to earlier FIGO staging versions. In previous prognostic models, stage was typically the most significant risk factor for malignant tumours11,39,40. Similarly, the FIGO stage exhibited the greatest impact on prognosis in our models. However, Grigsby et al. suggested that clinical outcomes remained heterogeneous despite having the same FIGO stage41. This observation indicated inherent limitations within the FIGO staging system. It primarily considers the extent, size, and metastasis of the tumor, while neglecting other prognostic factors such as pathological type, grade, and clinical treatment42. These factors were incorporated into our prognostic models, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the predictions, as evidenced by the superior AUC values for our models compared to those for the FIGO staging. Furthermore, the data for these factors are readily accessible in clinical practice.

There were some drawbacks that must be recognized in this study. Firstly, The SEER database did not contain detailed data on clinical characteristics, such as lymphovascular space invasion and HPV subtype, that are crucial for assessing the prognosis of CC. Secondly, the lack of information on lifestyle, such as age at first sexual activity, number of sexual partners and smoking history, limited the comprehensiveness of the study. Furthermore, the validation cohort was derived from a single center with a relatively small sample size (N = 125), which may raise concerns regarding potential bias. Therefore, further studies are necessary to improve accuracy and promote the model’s adoption.

Conclusion

Based on the established relationship between age and mortality, we defined young CC as occurring in individuals under the age of 36. The young CC group exhibited a better prognosis compared to other age groups, with independent prognostic factors including disease stage, tumor size, grade, histologic type, and surgical intervention. Recognizing that young CC patients represent a distinct cohort with unique clinicopathological features, we developed and validated prognostic models specifically tailored for this population. These models demonstrated good calibration and high accuracy, potentially serving as a valuable supplement to the current FIGO staging system.

Data availability

The data used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71 (2021).

Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem. (2023). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107 (accessed 30 July 2023).

You, L. et al. Worldwide Cancer statistics of adolescents and young adults in 2019: A systematic analysis of the global burden of Disease Study 2019. ESMO Open 6, 27–52 (2021).

Aida, Y. et al. Characteristics of cancers in adolescents and young adults compared with those in adults in their 60S: A single-center experience. Oncology 100, 140–147 (2022).

Chen, T. et al. Rising mortality rate of cervical cancer in younger women in Urban China. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 35, 593 (2020).

Motoki, Y. et al. Increasing trends in cervical cancer mortality among young Japanese women below the age of 50 years: An analysis using the Kanagawa population-based cancer registry, 1975–2012. Cancer Epidemiol. 39, 700–706 (2015).

Torres-Roman, J. S. et al. Cervical Cancer mortality among Young women in Latin America and the Caribbean: Trend Analysis from 1997 to 2030. BMC Public Health 22, 113 (2022).

Yuan, M., Zhao, X., Wang, H., Hu, S. & Zhao, F. Trend in cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates in China, 2006–2030: A Bayesian age-period-cohort modeling study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 32, 825–833 (2023).

Tanaka, S., Palmer, M. & Katanoda, K. Trends in cervical cancer incidence and mortality of young and middle adults in Japan. Cancer Sci. 113, 1801–1807 (2022).

Wojtyla, C., Janik-Koncewicz, K. & La Vecchia, C. Cervical cancer mortality in young adult European women. Eur. J. Cancer 126, 56–64 (2020).

Liu, Q. et al. Development and validation of a seer-based prognostic nomogram for cervical cancer patients below the age of 45 years. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 21, 620–631 (2021).

Kong, Y., Zong, L., Yang, J., Wu, M. & Xiang, Y. Cervical cancer in women aged 25 years or younger: A retrospective study. Cancer Manag. Res. 11, 2051–2058 (2019).

Pan, S., Jiang, W., Xie, S., Zhu, H. & Zhu, X. Clinicopathological features and survival of adolescent and young adults with cervical cancer. Cancer Control 28, 1399497690 (2021).

Isla-Ortiz, D. et al. Cervical cancer in young women: Do they have a worse prognosis? A retrospective cohort analysis in a population of Mexico. Oncologist 25, e1363–e1371 (2020).

Lau, H. Y. et al. Aggressive characteristics of cervical cancer in young women in Taiwan. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 107, 220–223 (2009).

Rutledge, F. N. et al. Youth as a prognostic factor in carcinoma of the cervix: A matched analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 44, 123–130 (1992).

Delaloye, J. F., Pampallona, S., Coucke, P. A. & De Grandi, P. Younger age as a bad prognostic factor in patients with carcinoma of the cervix. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 64, 201–205 (1996).

Chetty, R. et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. JAMA 315, 1750–1766 (2016).

Harrell, F. E. Jr. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis | Springerlink (2001).

Li, Z., Lin, Y., Cheng, B., Zhang, Q. & Cai, Y. Prognostic model for predicting overall and cancer-specific survival among patients with cervical squamous cell carcinoma: A seer based study. Front. Oncol. 11, 651975 (2021).

Feng, Y. et al. Nomograms predicting the overall survival and cancer-specific survival of patients with stage IIIC1 cervical cancer. BMC Cancer 21, 450 (2021).

Gauthier, J., Wu, Q. V. & Gooley, T. A. Cubic splines to Model relationships between continuous variables and outcomes: A Guide for clinicians. Bone Marrow Transpl. 55, 675–680 (2020).

Heinzl, H. & Kaider, A. Gaining more flexibility in cox proportional hazards regression models with cubic spline functions. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 54, 201–208 (1997).

Pelkofski, E. et al. Cervical cancer in women aged 35 years and younger. Clin. Ther. 38, 459–466 (2016).

Ruiz, R. et al. Clinical-pathological features and survival in young women with cervical cancer: A retrospective analysis from the Instituto Nacional De Enfermedades Neoplasicas. Rev. Peru Med. Exp. Salud Publica. 34, 218–227 (2017).

Higgins, G. D. et al. Increased age and mortality associated with cervical carcinomas negative for human papillomavirus rna. Lancet 338, 910–913 (1991).

Arezzo, F. et al. HPV-negative cervical cancer: A narrative review. Diagnostics 11, 952 (2021).

Macios, A. & Nowakowski, A. False negative results in cervical cancer screening-risks, reasons and implications for clinical practice and public health. Diagnostics 12, 1508 (2022).

Itarat, Y. et al. Sexual behavior and infection with cervical human papillomavirus types 16 and 18. Int. J. Womens Health 11, 489–494 (2019).

Zhong, X. et al. Prognostic nomogram for rectal Cancer patients with Tumor deposits. Front. Oncol. 12, 808557 (2022).

Deng, G. C. et al. Nomogram to predict survival of patients with Advanced and metastatic pancreatic Cancer. BMC Cancer 21, 1227 (2021).

Xu, Z. P., Gong, J. H., Gong, J. P. & Li, J. H. A nomogram predicting the outcome of gallbladder cancer patients with different target organ metastases. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 10016–10030 (2023).

Pachigolla, S. L. et al. A nomogram predicting early cervical cancer distant recurrence. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 111, e619–e620 (2021).

Kim, D. Y. et al. Preoperative nomogram for the identification of lymph node metastasis in early cervical cancer. Br. J. Cancer 110, 34–41 (2014).

Xie, G. et al. Calculating the overall survival probability in patients with cervical cancer: A nomogram and decision curve analysis-based study. BMC Cancer 20, 833 (2020).

Jiang, K., Ai, Y., Li, Y. & Jia, L. Nomogram models for the prognosis of cervical cancer: A seer-based study. Front. Oncol. 12, 961678 (2022).

Zheng, R. R. et al. Nomogram predicting overall survival in operable cervical cancer patients. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 27, 987–993 (2017).

Chen, W. et al. Nomogram for prognosis of elderly patients with cervical cancer who receive combined radiotherapy. Sci. Rep. 13, 13299 (2023).

Xiang, Y., Wang, F., Zhao, M. & Ling, X. Nomograms prediction for young and middle-aged patients (aged under 50) with metastatic cervical cancer: Based on seer database. Asian J. Surg. 46, 3252–3254 (2023).

Zhong, C. et al. A nomogram and risk classification system forecasting the cancer-specific survival of lymph- node- positive rectal cancer patient after radical proctectomy. Front. Oncol. 13, 1120960 (2023).

Grigsby, P. W. et al. Figo 2018 staging criteria for cervical cancer: impact on stage migration and survival. Gynecol. Oncol. 157, 639–643 (2020).

Soares, L. C., de Souza, R. J. & Oliveira, M. Reviewing Figo 2018 cervical cancer staging. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 102, 1757–1758 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Z. contributed to the conception of the study and review of the final manuscript; Q.Q. contributed significantly to data collection; Y.G. and W.Z. performed the data analyses and wrote the manuscript; F.G. and W.T. performed the analysis with constructive discussions. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, Y., Gou, F., Qin, Q. et al. Construction and validation of prognostic models for young cervical cancer patients: age stratification based on restricted cubic splines. Sci Rep 14, 29808 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81644-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81644-z

This article is cited by

-

The relationship between liver stiffness, fat content measured by liver elastography, and coronary artery disease: a study based on the NHANES database

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

The effects of message type and individual differences on the persuasiveness of public service announcements——the case of HPV vaccination

Current Psychology (2025)