Abstract

The poverty alleviation relocation program (PAR) is a milestone project in breaking spatial poverty traps in ethnic mountainous regions and provides a key solution for eradicating global absolute poverty. As direct participants in the restructuring of environmental and livelihood systems, the livelihood adaptation of relocated households is fundamental to the sustainable development of human-land systems in resettlement sites and the consolidation of the success of poverty alleviation. This research constructs an adaptive integration analysis framework of “external disturbance-adaptation process-adaptation outcome”, by utilizing questionnaire data from relocated households in the Liangshan Yi minority area of Southwest China, and employing a formative structural equation model to investigate the transmission mechanisms and heterogeneous effects of PAR on livelihood adaptation across different resettlement characteristics. The results indicate that: (1) External disturbance of PAR facilitates positive adaptation outcomes, with follow-up supportive policy as the most significant determinant, which contributes directly to adaptation outcomes and indirectly through improved learning and self-organization capacity. Conversely, risk perception has a negative impact on adaptation outcomes and further exacerbates adverse impacts by reducing buffering capacity. (2) The pathways influencing subjective and objective adaptation outcomes demonstrate heterogeneity. PAR has a positive impact on subjective adaptation, but a non-significant effect on objective adaptation, self-organization capacity and buffering capacity are the most important direct drivers and mediating variables affecting both, respectively. (3) Resettlement characteristics exert a moderating effect on livelihood adaptation. The positive effect of follow-up supportive policy on learning capacity and the marginal contribution of learning capacity to adaptative strategies being greater in mid-to-long-term resettlements. Buffering capacity of village resettlements and subjective adaptation of town resettlements are more beneficial from follow-up supportive policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Eradicating poverty is a major global challenge and is prioritized as the foremost goal in the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDGs)1. Over the past decades, various anti-poverty strategies have been developed globally2, with migration and relocation being effective means to combat poverty vulnerability and are widely advocated3. Governments and international organizations often use planned relocation to achieve development and environmental goals, especially in developing countries4. For example, in Southeast Asia, Thailand created Self-help Settlements for Hill Tribes and proposed an economic development plan to alleviate poverty and promote economic growth among ethnic minorities in the northern mountains through resettlement. Laos’ development policy also prioritizes the relocation of highland ethnic minorities. In Africa, Ethiopia implemented large-scale resettlement in the 1970s with government funding to alleviate famine caused by natural and manmade disasters in the northern regions5. Similarly, Mozambique views planned resettlement as crucial for reducing flood vulnerability and improving living conditions for its poorest citizens6.

Poverty is tightly associated with ecological degradation and exhibits geographical clustering7. Covering a quarter of the Earth’s land surface, Mountainous regions are exposed to more frequent and severe poverty risks, characterized by marginalization, inaccessibility and fragility8. These remote regions suffer from poor infrastructure, limited market access and politically disadvantages9, inhabitants heavily depend on natural resources, with many engaged in subsistence farming activities. The homogeneous economic structure and weak development capabilities have long excluded it from economic growth10. Meanwhile, these areas are prone to severe natural disasters that are highly susceptible to irreversible damage. Any disturbance may trigger a cascade reaction in mountains, resulting in dramatic changes and losses, damaging infrastructure and livelihoods, and compressing the living space for residents11,12. In China, 90% of the impoverished population is concentrated in the central and western mountains13, where insitu poverty alleviation efforts face significant challenges and diminishing marginal returns. Hence, the Chinese government has implemented PAR program and regards it as flagship project to end remaining absolute poverty during the “13th Five-Year Plan” period by resettling poor people from fragile ecological environments to more habitable villages and county towns14, approximately 10 million registering impoverished households from 22 provinces were relocated, equivalent to the size of the population of a medium sized country4, the developmental impacts of this initiative far surpass those of similar projects in the world15, which provides an opportunity to understand environmental and poverty related issues in a rapidly changing global context.

The essence of PAR is to provide potential livelihood opportunities through spatial restructuring, this initiative aims to restore and rebuild livelihood capacities, reshape livelihood modes, and enhance resilience to future changes and challenges, ultimately achieving a more optimal balance within sustainable livelihoods16. Supportive policy from central and local governments plays a crucial role as external forces in helping households reshape their livelihoods. However, as a top-down leading project, relocation carries inherent risks, changes in households’ access to external resources and opportunities can alter their production structures and arrangements12, this affects existing livelihood capital combinations and may interrupt livelihood process. Huge economic burdens and integration costs could potentially push households into secondary poverty17, creating tensions and conflicts between migrants and communities, ultimately offsetting the benefits of relocation18. The exact impact of PAR on the livelihood of migrants is widely discussed, existing studies have focused on the links between relocation and income19, livelihood capital, strategy choices18, risk vulnerability and livelihood resilience20. Adaptation is crucial in buffering human vulnerability to environmental changes21. As the fundamental socioeconomic units of migrant community development and the direct perceivers and bearers of socio-ecological reconstruction, having moved from their previous villages at unprecedented scales and speeds into unified settlements, relocated households urgently need to reestablish connections with the local environment and undergo multifaceted adaptation processes22.

Adaptation emphasizes the ability of systems to transition to new states by adjusting to external changes23, encompassing climate change, natural disasters, rural tourism, rapid urbanization, and other government interventions. With socioeconomic development, the field of adaptation study has gradually shifted from national and regional scales to focus on sensitive rural and community groups. Adaptive capacity, a core attribute and key factor in adaptation, has been widely explored by scholars, including frameworks and models of adaptive capacity24, multiscale assessments25, the relationship between adaptive capacity and multiple risks, adaptive strategies and outcomes21,26, advancing adaptation from theoretical research to practical application. Despite significant attention and a solid theoretical foundation on livelihood adaptation to rapid environmental change, research limitations persist. First, existing research primarily addresses climate change and natural disasters, neglecting the scientific adaptation of migrants to combined natural and social disturbances. The resettlement of ethnic minorities in mountainous areas involves cultural preservation, ethnic unity, and political stability, sustainable development are even more severe, requiring a comprehensive evaluation of resettlement adaptations. Second, previous studies have overlooked the fact that livelihood adaptation is an organic systemic process21, mostly staying in isolated interactions. Furthermore, relocation acts as a double-edged sword, most studies measure its impact on migrants’ livelihoods from either a risk or support perspective, lacking a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms and processes through which relocation induced constraints and opportunities affect livelihood adaptation. Third, the impact of relocation on livelihoods is multidimensional and profound, current studies often assess relocation outcomes from a single perspective, such as income or life satisfaction. However, livelihood adaptation involves multiple objectives, addressing both material aspects (physical and economic) and mental aspects (social and psychological)27.

Given this, the study constructs an integrated adaptation analysis framework of “external disturbance-adaptation process-adaptation outcomes” for PAR. Using a sample of 466 relocated households in ethnic mountains of Southwest China and employing PLS-SEM techniques, it aims to clarify the mechanisms and effects of PAR on livelihood adaptation, revealing the formation logic and key pathways heterogeneity of both subjective and objective adaptation in different resettlement characteristics. Theoretically, this study constructs a logical framework for livelihood adaptation chains, providing a research scheme for systematically explore the complex interactions between relocation and livelihood adaptation. It broadens the perspective on environmental change and enriches the understanding of adaptation outcomes. Practically, it offers new insights into sustainable livelihoods of relocated households by taking adaptation as a breakthrough, supports targeted interventions and facilitates relocated households to integrate into new communities. Meanwhile, it provides valuable references for developing countries to alleviate poverty and achieve the 2030 SDGs.

Materials and methods

Study area

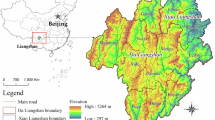

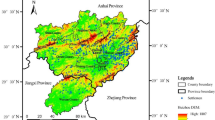

Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture lies in the Southwestern Sichuan Province at the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau in China, it spans geographical coordinates from 100°03’E to 103°52’E and 26°03’N to 29°18’N (Fig. 1), covering a total area of 60,400 km2, 71% of which are mountainous terrain, with severe challenges between environment protection and livelihood activities of residents. As a crucial component of the ecological barrier in the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, the region is restricted or prohibited from largescale development, the environment is fragile and sensitive, with strong tectonic earthquakes and frequent mudslides, posing a serious threat to the lives and property of residents annually. The minority groups gather in this area, which accounts for 58.41% of the total population, known as the largest Yi ethnic settlement in China. Due to natural conditions, geographical constraints, and historical factors, it was more prone to become impoverished, once belonging to concentrated contiguous poverty-stricken areas in China, 96.55% of the counties were once designated as national and provincial poverty-stricken counties, over 60% of the registered poor reside in high mountain and rocky desertification, highly rely on traditional farming and herding, with limited livelihood means and transition chances.

Since the 1990s, government sponsored relocation programs have been systematically carried out to help rural villagers seek alternative livelihoods by moving from mountains to lowlands and plains. In particular, after the central government attached great importance to the work of PAR in 2015, relocation emerged as a pivotal strategy for poverty alleviate in Liangshan Prefecture, during the “13th Five-Year Plan”, a total of 1,468 resettlement sites were established, the investment amounted to various funds totaling 21.1 billion CNY, benefiting approximately 74,400 households and 353,200 poor individuals, which encompasses 36% of the registered impoverished population in this area and 26% of the total undertaking relocation tasks in Sichuan Province, the scale is at the forefront nationwide. As an important epitome of the PAR in western minority mountains, the experiences and practices in Liangshan Prefecture have gained recognition at both national and provincial levels, providing an important case to observe the implementation of relocation programs.

Data source and processing

The research data were collected by participatory rural appraisal method, interview and field investigation was carried out in January 2022 through the following procedures. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the relocation information in research area, we first interviewed the officials from relevant departments of the Development and Reform Commission and the Rural Revitalization Bureau of Sichuan Province and Liangshan Prefecture. Subsequently, a preliminary survey was randomly conducted on 20 households in 5 resettlement sites, and follow revisions were made to the questionnaire in light of the feedback. Considering the representativeness of samples and the feasibility of implementation of the scheme, Zhaojue, Xide, Meigu and Yuexi, the four counties that served as the earliest PAR pilot areas in Sichuan Province were selected as case studies for the formal investigation. Each county plays a dual role of national importance in ecological conservation and poverty alleviation and has been designated as the key county supported by national rural revitalization subsequently. based on resettlement time, mode, and size criteria, 3–4 resettlement sites were chosen within each county, sample size was determined according to population weighted randomization. The survey was conducted face-to-face by well-trained university students familiar with the local language, resulting in a 100% response rate. After data cleaning and removing incomplete samples, 466 valid samples were obtained. The household level questionnaire covered basic family characteristics, received assistance, risk perception, livelihood capital, adaptation strategies, and social integration. Community interviews included resettlement information, infrastructure, public services, industrial development, and community governance.

Theoretical background

Adaptation emphasizes adjustments made within human-environmental systems in response to observed or anticipated internal or external stimuli, aiming to mitigate risks or develop favorable opportunities21,24. As research and empirical observations on adaptation accumulate, various adaptation methods and analytical frameworks for different natural and social contexts have continuously emerged21,24,28, providing a scientific basis for the quantitative study of adaptation. However, there remains insufficient attention to the adaptation of micro-level livelihood systems among farmers, and a unified, widely accepted analytical framework for adaptation is still lacking21.The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) proposed by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) provides a standardized tool and a systematic approach for livelihood research, it is an integrated analytical framework for addressing poverty related issues, with the context of vulnerability, livelihood capital, structural and process transformations, livelihood strategies, and livelihood outputs as the crucial components for identifying livelihoods factors and their interactions29. Since 1980, sustainability science began to understand the interactions within coupled human-environment systems from the perspectives of vulnerability, resilience, and system adaptability21. Due to stand alone adaptation research started late, it mainly draws on both thinking of vulnerability and resilience approaches30.Vulnerability theory emphasizes an actor oriented approach, viewing adaptation as a decision making process, while overlooking the dynamic changes in system structural elements31. In contrast, resilience thinking focuses on the interconnections between elements, highlighting adaptive capacity and how to maintain this capacity to address future uncertainties, but lacks sufficient attention to the behavioral effects of adaptation actors. Each of these analytical paradigms has its strengths and weaknesses. Moreover, a common characteristic between previous research frameworks and livelihood adaptation methodologies is the failure to recognize livelihood adaptation as an integrated, systematic process21 .

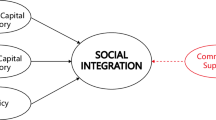

As a common thread between the vulnerability and resilience frameworks, adaptive capacity is a key system attribute that enables the cycle of adaptive processes in the face of uncertainty. It is strongly influenced by management, governance, and institutions31, while the perception and anticipation of external environmental changes release critical motivation or “energy” for its activation32. Adaptive capacity is closely linked to the assets one possesses, which form a reserve that can be utilized to support income-generating efforts, survival strategies, and other advantages. These assets can be preserved, accumulated, traded, or distributed as needed and their interconnections shape the anticipated livelihood outcomes33. The stronger the adaptive capacity accumulated within a system, the greater chance the system will eventually reach an “optimal” state31. At the same time, choosing adaptive livelihood strategies is crucial for ensuring farmers’ survival in the face of environmental change21, the ability of households to mobilize scarce resources when confronted with natural environmental and social policy impacts largely determines their adaptive responses, thereby influencing their livelihood adaptation outcomes.Therefore, adaptive capacity and adaptive strategies are organically and closely linked, forming a key part of the adaptation process. Accordingly, this study takes the SLF as foundational guidance, integrating actor orientated and systemic pathway analysis to construct a comprehensive livelihood adaptation, advocating the construction of a chain adaptation transmission path of “external disturbance-adaptation process-adaptation outcomes“(Fig. 2), the framework emphasizes the roles of external environment, internal livelihood endowments and dynamic system processes in influencing the microscale adaptability of households.

Specifically, PAR involves a dual transformation and reconstruction process of the sociocultural and natural ecological spaces for impoverished groups, the geographic area, field of action and area of existence of households are switched. As a double-edged sword, PAR presents both opportunities and risks. After relocation, the government implements preferential policies and institutional arrangements, including industrial restructuring, employment support, efficient public resource allocation, community building, and social security10, providing an excellent opportunity for relocated households to explore the potential of external resources4,34. Meanwhile, households are faced with major changes in production and lifestyles, resulting in new contradictions and constraints of “human-industry” livelihood space. Under the combined influence of the supportive pull force from subsequent assistance and the push force from a vulnerable risk environment, adaptation and response become inevitable. On one hand, relocated households gain access to improved habitat, secure housing and subsidies, at the same time, they may encounter food insecurity, lack of sustainable income, increased living costs, which directly affect their sustainable income increase and sense of belonging. On the other hand, relocation as an external disturbance can directly impact farmers’ basic capabilities, making it difficult for their livelihood system to maintain its previous stable state. By accumulating and reorganizing household assets, their functional activities adjust autonomously or under government or organizational guidance. They may adopt adaptive behaviors, either proactively or passively, to respond to changes in the livelihood environment, leading their livelihood system into a new state aimed at meeting the goals of stakeholders. Notably, the effect of relocation on livelihood adaptation may be embedded in the attributes of resettlement characteristics16,35.

Indicator design and descriptive statistics

The external disturbances manifest as both opportunities and risks, The government’s support measures offer livelihood opportunities for migrants through financial aid and capacity building. In line with the State Council’s 2020 policies, employment opportunities, training programs, public services, entitlements protection and comprehensive governance are taken as the key indicators of follow up supportive policy. Risk exists in reality or expectation and influences decision making only when perceived. Based on the risk management by World Bank36 and existing risk identification in resettlement37,38, as well as the actual situation in Liangshan Yi Minority Area, this study specifically summarized risk elements across policy, natural, social, living, production, and cultural aspects and employed indicator of risk severity perceptions.

Adaptive capacity is represented by a set of resources for managing disturbances and addressing current or future risks. Learning capacity, buffering capacity, and self-organization capacity are key elements that reflect the essence of adaptive capacity21,39,These capacities work synergistically, buffering capacity provides essential support for both learning and self-organization, while enhanced learning capacity improves the coordination and cooperation mechanisms within self-organization, which in turn strengthens buffering capacity, thereby forming a coherent and mutually reinforcing adaptive response. Learning capacity encompasses not only the ability to acquire skills but also the ability to exchange new knowledge and innovate production techniques40, which was mainly captured by education level, information channel, policy awareness and vocational skill. Buffering capacity, the first protective barrier of livelihood systems, helps maintain functional attributes and organizational structure in response to diturbances41, it primarily depends on the resources available to the systems, including natural, physical, human and financial capital. Self-organization capacity refers to the ability of individuals to establish flexible and dynamic networks of communication and mutual assistance and to integrate into the local social, economic and institutional environment39, this is supported by influential ties, group engagement, neighborhood interactions, neighborhood trust, and social networks.

Adaptative strategies refer to the selection and combination of activities chosen by households to sustain their livelihood42, are categorized into five types, namely, assistance, contraction, retention, expansion and adjustment43,44. Assistance involves relying on external aid to cope with disturbances, such as borrowing from relatives and friends or awaiting government relief. Contraction involves reducing production or consumption, such as cutting expenses or Utilizing savings, thus narrowing the scope of livelihood diversity. Retention indicates that households maintain their original livelihood patterns after relocation. Expansion denotes increasing income sources through production scaling, investment diversification, livelihood diversification, and self-employment to mitigate uncertainty risks. Adjustment indicates households adopt different practices to restructure agricultural production or switch from agricultural to non-agricultural livelihood activities.The key livelihood strategies adopted by households in response to risks and challenges constitute their core adaptive measures. The transition from assistance-based to expansion and adjustment strategies illustrates an evolution from passive, low-level adaptation to more proactive and advanced approaches.

Adaptive outcomes refer to the effects that arise when farmers adopt strategies to cope with livelihood pressures. After large-scale relocations ended in 2020, the PAR entered a phase of post-relocation support, aiming to achieve stable resettlement, employment, and prosperity. In practice, improving economic conditions is the first milestone for PAR migrants to integrate into new communities, while psychological integration is regarded as the final and most advanced stage45. Drawing on Chen et al.(2018)21, both objective and subjective adaptations are considered in this analysis. Objectively, households must maintain income and living standards, with per capita income supporting consumption and diverse livelihoods ensuring income stability46. Subjectively, emotional integration, social cohesion and psychological well-being have also been identified as beneficial complements to economic indicators, belonging and identity are essential for achieving stability27, and thus livelihood perception, reflecting subjective adaptation, is expressed by adaptive evaluation, future confidence and identity recognition. Detailed in Table 1.

Methods

Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a statistical technique employed to establish, estimate and evaluate logical links among multiple factors. A complete SEM covers two parts: the structural model and the measurement model, in which the measurement model can be either formative or reflective47, ignoring the difference might lead to logical confusion and biased estimation results48. Based on the causal relationships between measurement indicators and latent variables, as well as the correlation among measurement indicators, and with reference to the study of Jarvis49, this research aligns with the characteristics of formative measurement models.

The internal structural model describes the causal relationship between latent variables. The equations are as follows:

In these equations, η represents the vector of endogenous latent variables, ξ denotes the vector of exogenous latent variables, α is the constant term, Γ represents the path coefficients, and ζ is the vector of residuals. In this study, follow-up supportive policy and risk perception are the exogenous variables, while adaptive capacity, adaptive strategies and adaption outcomes are the endogenous variables.

The external measurement model describes the relationship between latent variables and each observed indicator, with the equation expressed as follows:

Where \(\:x\) and \(\:y\) are observed indicators for the exogenous latent variable ξ and the endogenous latent variable η respectively. Π denotes the multivariate regression coefficient matrix, and δ represents the residual term.

This study emloys PLS-SEM technique to estimate the parameters of livelihood adaptation mechanisms among relocated households affected by PAR disturbances. Compared to covariance-bases SEM(CB-SEM), PLS-SEM has notable advantages in handling formative measurement models, offering greater stability in small-sample estimation and better suitability for theory exploration and prediction50.Additionally, unlike CB-SEM, which relies on normality assumptions, PLS-SEM does not require the sample data to follow a normal distribution, allowing for greater flexibility. Given that the sample size is less than 500 and the analysis is exploratory, focusing on the theoretical mechanisms of livelihood adaptation with a formative measurement model, PLS-SEM deemed more appropriate. SmartPLS 3.0 software was thus used for model estimation.

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols were approved by Mianyang Teachers’ College and Liangshan Prefecture Development and Reform Commission. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Results

Model testing

Formative model measurement indicators do not require internal consistency, therefore, reliability assessment is not practically significant51. The primary focus should be on ensuring model indicator and construct validity. Indicator validity is measured based on weight significance and multicollinearity, while construct validity is mainly assessed through discriminant validity, the coefficient of determination for endogenous latent variables, predictive relevance, and goodness of fit52.

Measurement model estimation

The weight of measurement indicators is presented in Fig. 3. According to recommendations by Chin & Marcoulides47, measurement indicators should possess a minimum value of 0.1 and demonstrate statistical significance. Using the bias corrected Bootstrap technique with 5000 replicate samples, the findings indicate that most indicators satisfy these requirements. In formative structural equation models, it is inappropriate to eliminate indicators based solely on statistical results, as removing components may alter the meaning of latent variables. Therefore, following Dowling53, it is advisable to retain all indicators.

Multicollinearity of the measurement indicators is tested subsequently. The variance inflation factor (VIF) values for each measurement indicator varied from 1.0 to 1.5, all of which are below the strict threshold of 3.354, indicating that there is no collinearity problem among the indicators, suggesting well indicator validity.

Structural model estimation

Discriminant validity is a crucial reference to assess the validity of structural model, the absolute values of correlations between exogenous constructs were all less than recommended 0.755 (Fig. 4), generally suggesting that the model structure is stable.

The coefficient of determination (R2) indicates the extent to which endogenous variables are explained. Generally, R2 of 0.10 is considerable and the model has practical value, specifically, in PLS-SEM, the R2 value of 0.60 is deemed substantial, 0.33 moderate, and 0.19 weak47. As shown in Fig. 3, the R2 value for adaptation outcomes is 0.353, exceeds moderate explanatory, indicating that incorporating both follow-up supportive policy and risk perception into the analytical framework enhances understanding of adaptation outcomes. Nevertheless, the relatively low R2 values were observed in adaptative strategy, buffering capacity and learning capacity, implying other factors besides external disturbances of PAR still played an important role.

Predictive relevance (Q2) mainly reflects the influence of exogenous variables on endogenous variables, Q2 > 0 indicates that the model presents predictive relevance. Results showed that Q2 of endogenous latent variables varied from 0.005 to 0.082, greater than the critical value of 0, indicating the model took strong predictive ability.

Goodness-of-Fit is an important index indicates the overall predictive power of the model fitness. Tenenhaus proposed a GoF index for PLS path models56, with values ranging from 0 to 1, where a higher GoF value signifies a better fitting path model. In this study, the overall GoF is 0.284, exceeding the moderate fit standard of 0.25 suggested by Wetzels[[57]], indicating a satisfactory model fit, the model’s design and application are reasonable.

The distribution characteristics of the latent variables indicate that the mean values of all variables range from 0.444 to 1.289 (Table 2). Standard deviations are generally small, reflecting a high degree of internal consistency within each latent variable. Most variables approximate a normal distribution, while the adaptation outcomes show higher skewness and kurtosis, indicating a relatively concentrated data distribution with a left-skewed characteristic, where a few households exhibit extreme low values.

Direct and indirect effects of PAR on livelihood adaptation

The follow-up supportive policy and risk perception jointly shape adaptive capacity and outcomes of relocated households (Fig. 3). Stronger supportive policy enhances adaptive capacity, while higher risk perception weakens buffering capacity. Overall, PAR supports sustainable livelihoods by promoting positive outcomes. Although both factors significantly impact adaptive outcomes in opposite ways, the positive effects of policy outweigh the limitations of risk perception. Employment opportunities, entitlement protection, and comprehensive governance emerge as pivotal supportive elements, underscoring the essential role of government assistance in facilitating adaptation.

Adaptive capacity serves as crucial internal driver of adaptive outcomes. Learning capacity, buffering capacity, and self-organization capacity all significantly positively influence adaptive outcomes (Fig. 3). Among these, buffering capacity makes the greatest marginal contribution, supported by assets like cultivated land, livestock, consumer durables and deposits, these resources as part of household wealth, enable relocated households to smooth short-term production and consumption and maintain the basic welfare58. Self-organization capacity follows in importance, while learning capacity has a relatively weaker impact. However, the impact of adaptive strategies on outcomes is limited, probably due to high transition costs and mobility barriers in the uban-rural dual system3, factors such as human capital costs and the household registration system restrict labor tansfer and hinder migrants’ upward mobility to the middle-income group. Moreover, relocation disrupts farmers’ spiritual coonection to land, weakening their attachment and willingness to engage in pro-environmental behaviors59. The benefits of non-agricultural livelihood transformation may also take longer to emerge.

External disturbances indirectly influence migrants’ adaptive strategies and adaption outcomes by mediating the spontaneity mechanism of adaptive capacity. Supportive policy significantly influences adaptive strategies through partial mediation (VAF = 53.65%)60, with learning capacity as a key mediator, the path coefficient of FP → LC → AS is 0.033 (Table 3), highlighting the necessity of external interventions for non-agricultural transitions. PAR mitigates employment challenges through measures such as public welfare positions, poverty alleviation workshops, labor export, entrepreneurship assistance, and skills training, which enhance skills and facilitate non-agricultural employment opportunities3. Learning and self-organization capacities partially mediate the effect of supportive policy on adaptation outcomes, enabling households with higher learning and self-organization capacities to better utilize external opportunities and adopt strategies that promote family development. Conversely, risk perception has a significant negative indirect effect on adaptive outcomes. The path coefficient for RP→ BC → AO is -0.067, implying that the relocation related risks reduce buffering and exacerbate shocks to adaptive outcomes.

Impact of PAR on subjective and objective adaptation

PAR differentially impacts migrants’ subjective and objective adaptation outcomes, with a stronger influence on subjective livelihood perception than objective livelihood quality (Table 4). Livelihood perception is jointly affected by follow-up supportive policy, risk perception and adaptive capacity. Follow-up supportive policy directly and indirectly enhances livelihood perception by strengthening learning and self-organization capacities, with a total effect of 0.374 (Table 4). Self-organization capacity emerges as the most critical direct and mediating driver, supported by the whole village relocation model, which fosters public identity, social cohesion and shared identification61. Besides, enhanced infrastructure and public services in the resettlement sites boost satisfaction and wellbeing35. Community based employment, recreational activities and professional cooperatives expand social spaces for migrants, the close neighborly relationships and stable social networks facilitate information sharing, capital substitution and psychological support, aiding migrants in adapting smoothly to new social and institutional environments62,63.

The direct impact of PAR on objective adaptation outcomes is insignificant, with livelihood quality primarily influenced by buffering capacity and adaptive strategies, highlighting the importance of migrants’ capital reserves and adaptive behavior adjustments. Buffering capacity, as the key direct driver and mediator between risk perception and livelihood quality (Tables 4 and 5), relies on maintaining and accumulating household assets64. However, relocated households, often initially vulnerable and impoverished, generally lack sufficient capital reserves to withstand risks. Besides, concentrated resettlement and compact housing designs reduce living and production space, eliminating courtyard economies such as livestock rearing and vegetable cultivation. These limitation weaken the capacity to absorb disruptions and maintain functionality under internal and external disturbances. Furthermore, buffering capacity is also a crucial driver in facilitating migrants’ transition to non-agricultural strategies and improving income, with a BC → AS → LQ path coefficient of 0.015.

Multigroup analysis based on different resettlement characteristics

In the process of livelihood adaptation, migrants experience different adaptation cycles and varying levels of welfare under different spatiotemporal conditions. Their ability to digest and absorb the impacts of relocation varies. Differences in the loss of livelihood resources and feasible capabilities lead to varying risk perceptions, resulting in differentiated livelihood levels and place attachment27. Based on the observation of adaptability principles, a three year time threshold represents the shift of relocated households from improving personal identity and productivity to a steady recovery stage65. Therefore, the study divides the resettlement time of migrants into two stages: short-term (less than three years), and mid-to-long-term (three years or more). Additionally, China’s resettlement is predominantly within the county and can be categorized into towns and villages based on the distance of relocation27. the multigroup analysis model (MGA) was further employed to investigate the differences in the mechanism of migrants’ livelihood adaptation under the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of relocation. The results are shown in Table 6.

The moderating effect of resettlement time on livelihood adaptation

In the path coefficient difference test between short-term and mid-to-long-term resettlement, the differences for the FP-LC and LC-AS paths are − 0.601 and − 0.236, respectively, and are significant at the 5% and 10% levels, while there is no significant difference between the other paths (Table 6). The results show that, compared with short-term resettlement, the marginal effect of policy synergy on the learning capacity of mid-to-long-term resettlement is higher, and the improvement of learning capacity has a greater impact on the adaptive strategy. This may be because in the initial stage of relocation, families often face difficulties in exchanging labor in the market system due to low education levels and a lack of vocational skills. A longer relocation period implies more stable and robust supportive measures, as well as more optimized resource allocation and accumulation. Long-term and continuous policy support enhances migrants’ ability to acquire and accumulate survival skills, knowledge and information, as well as self-recognition. Generally speaking, improvement in the learning capacity, makes migrants more inclined to participate in the urbanization and industrialization process, thus, they can achieve a shift in livelihood strategies to non-resource-dependent options, and engage in non-agricultural employment or more advanced occupations away from home43,66.

The moderating effect of resettlement mode on livelihood adaptation

The comparison of path difference coefficients for livelihood adaptation between village and town resettlement shows significant differences in the FP-BC and FP-LP paths, with difference coefficients of 0.447 and − 0.528, respectively, significant at the 10% and 1% levels (Table 6). This indicates that the positive impact of follow-up supportive policy on the buffering capacity of village resettlement is significantly higher than that of towns, and that, conversely, the positive synergistic effect of policy on the livelihood perception of town resettlement is greater than that of villages. This may be because most village resettlement households come from nearby villages, generally moving from the mountains to the plains or from rural to rural, which makes resettlement less costly, slightly alters their mode of production and way of life, and preserves their spiritual connection with the land, the roots of agricultural production are maintained27. Additionally, the infrastructure at the resettlement sites is more advanced than in the original locations. Improved transportation shortens the distance between households and markets, facilitating timely access to agricultural inputs and technology. Futhermore, poverty alleviation efforts focus primarily on agricultural activities within the villages, the development of industrial parks enables farmers to become agricultural workers, earning rent and dividends through land transfers or shares, thus promoting the development of agricultural production in resettlement areas and the accumulation of household livelihood capital67. In the town resettlement model, the original material foundation and social environment of the farmers undergo significant changes and they are forced to participate in the urban economy, experience higher resettlement costs68. Nevertheless, compared to the village resettlement, town resettlement offers significant advantages in resource provision. On one hand, the larger population size and resource concentration in towns maximize the efficiency of investments and use of public goods, which facilitate migrants’ quick adaptation to new lifestyles and foster attachment to their new communities69. On the other hand, towns have a larger labor market, which helps unskilled farmers find jobs and integrate into the local economy and social system70.

Discussions

Heterogeneity of subjective and objective adaptation outcomes of relocation

PAR has been shown to be a transformative force in farmers’ livelihoods33, removing spatial constraints on survival, but the multiple overlapping of risk factors still pose a serious challenge to the livelihood adaptation for relocated households. Most studies suggest that PAR positively contributes to a new cycle of sustainable livelihoods18,71.Similarly, this study finds that relocation supports migrants adapt well, particularly in terms of subjective livelihood perception. This is largely attributed to the voluntary nature of relocation, and migrants are more likely to embrace comfortable, safe, and accessible residential conmmunities, which in turn enhances their subjective wellbeing72. However, different from the results of Lo & Wang34 and Liu18, the promotion of objective livelihood quality through relocation is not evident, reflecting the economic incompatibility and marginalization of migrants72. Possibly due to the limited compensation for centralized resettlement individuals, coupled with various forms of economic deprivation or ineffective relocation cost control73. Although the government has provided non-agricultural employment opportunities through the construction of poverty alleviation workshops and industrial bases, these efforts face issues such as inadequate industrial support, poor operational quality, limited job absorption, lack of order capacity, low wages, occupational prejudice, and insufficient conversion of skills training into practical activities12, and the lack of strict labor contracts results in informal employment characteristics. Additionally, migrant work as their main means of livelihood33, the COVID-19 epidemic that has been raging since 2020 severely impacted migrants who rely on external employment, leaving many in a state of prolonged unemployment74. After relocation, migrants face higher expenses for housing, food, education, and healthcare75. Consequently, they experience economic risks characterized by low-income stability and high living costs. Significant improvements in financial conditions are essential for successful economic integration into the new community for migrants45. if their income situation does not improve sustainably, they are easily trapped in transitional or developmental poverty again.

Adaptive capacity is the decisive factor in adaptation improvement

The government plays a leading role in the process of PAR, and the subsequent support policy is the necessary external support for migrants’ livelihood adaptation76. As a social development policy, part of the government’s transfer payment is delivered in the form of capital rather than income, with the purpose of helping impoverished families enhance their development capacity. The self-growth of migrants’ livelihood systems and the adaptive change of the structure and function of internal elements of the system are crucial for successful adaptation. Research shows that adaptive capacity is not only a direct positive factor in promoting adaptation outcomes but also a mediating variable that indirectly affects migrants’ adaptive strategies and outcomes through subsequent support and risk perception of external disturbances. which emphasizes the importance of adaptive capacity in forming adaptive strategies, coping with pressure and utilizing opportunities, playing a crucial role in long-term development of actors77. Specifically, self-organization capacity and buffering capacity are key factors driving livelihood perception and livelihood quality, respectively. The positive impact of self-organization capacity on livelihood perception aligns with Zhu’s research27. Cultivating harmonious neighborly relationships and establishing stable social networks are essential foundations for migrants to integrate into their new lives. In contrast, buffering capacity is less effective in mitigating and resisting risks. Lu’s research found that buffering capacity has a threshold effect on poverty vulnerability mitigation and that low buffering capacity exacerbates the risk of disaster shocks and prevents migrants from adjusting production and livelihoods in response to environmental changes78. Migrants mainly come from remote mountainous areas with relatively low productivity, previously relying on agriculture for income, and most lack capital accumulation38. After relocation, although their houses have been greatly improved, they only have the function of living, with restricted property rights, and most families have lost their original cultivated land, making it difficult to increase asset value through material capital18. Coupled with a lack of critical skills for non-agricultural work3, unstable income streams and a significant increase in rigid daily expenses have forced households to use their limited savings to combat risks and rebuild their livelihoods.

Livelihood adaption variance under distinct relocation characteristics

Under different spatiotemporal characteristics of relocation, the environmental conditions, institutional arrangements, and resource endowments that migrants face can vary significantly, potentially leading to different adaptation outcomes27. This study shows that resettlement characteristics have a moderating effect on migrants’ livelihood adaptation, with heterogeneity in adaptation mechanisms under different spatiotemporal conditions. Long-term relocated households benefit from government support by acquiring and accumulating survival skills, obtaining higher awareness of job requirements and more information acquisition16,79. This reduces their dependence on cultivated land, enabling livelihood transformation and the establishment of stable livelihood patterns, which supports the previous findings of Lo &Wang34 and Rogers22 that emphasize the importance of ongoing support for the long-term success of resettlement projects18. Different resettlement modes result in significant differences in lifestyle, living environment, and social environment. Town resettlement is characterized by industrial agglomeration and population concentration, access to comprehensive infrastructure and public services, and more non-agricultural employment opportunities. Village relocation modes involve relatively minor changes to lifestyle and livelihoods38. Consistent with Zhu’s research findings27, the advantages of town resettlement in enjoying high quality public services and diverse employment provided migrants with more emotional support. This is largely due to the Liangshan Prefecture government’s implementation of a three year action plan for urban large scale resettlement communities in 2020, which connects universities, social work agencies, and charitable organizations to bring public services into communities, for example, the implementation of “Four-thirty Classes” and daycare centers has helped vulnerable groups better integrate. However, town resettlement also faces higher relocation costs, creating a more urgent need for building adaptive capacity.

Limitations

This study adopts a holistic perspective and provides valuable insights into livelihood adaptation among migrants in the context of PAR. However, several limitations remain. Firstly, the dynamic and open nature of the livelihood system makes it challenging to capture the evolution of adaptations using static cross-sectional data. Additionally, there may be interactions, nested relationships and cumulative iterative cycles among the factors influencing livelihood adaptation, future research should focus on tracking the dynamic decision-making processes of adaptation and implementing phased adaptation management based on adaptation cycle theory, taking into account the complexity and phased characteristics of migration policies. Secondly, adaptive behaviors are diverse, and the flexibility of adaptative strategies under changing conditions, as well as the potential for transformative adaptation, deserve further attention. Finally, the survey was conducted in Liangshan Yi minority area, a typical region of nationwide relocation with prominent human-land conflicts. Due to the unique economic and social conditions and regional policy differences in the southwestern ethnic mountainous areas, relocation may exhibit distinctive features, therefore, generalization the conclusions requires expanding the study area to support the contextualized nature of the theory.

Conclusions and policy implication

Conclusions

Based on the theory of sustainable development, vulnerability and resilience, this study constructs an adaptive integration framework of “external disturbance-adaptation process-adaptation outcome” for relocation, takes Liangshan Yi minority areas as a case study, PLS-SEM and multigroup analysis were used to reveal the mechanism and driving effect of relocation on household livelihood adaptation, and further identify the heterogeneity of the formation logics and key paths of subjective and objective adaptations under different resettlement characteristics. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

PAR can promote positive adaptation outcomes, with the synergistic effects of subsequent support outweighing the constraints posed by risks. Follow-up supportive policy and risk perception not only act directly on adaptive capacity, adaptative strategies and adaptation outcomes, but also indirectly influence adaptation outcomes through the mediating role of the adaptive capacity. Follow-up supportive policy contributes to learning and self-organization capacities, leading to positive adaptation outcomes and serving as key factors in influencing these results. Conversely, risk perception negatively impacts buffering capacity, adaptive strategies, and adaptation outcomes.

-

(2)

The influence paths of subjective and objective adaptations exhibit heterogeneity, with subjective livelihood perceptions being affected by a combination of follow-up supportive policy, risk perception and adaptive capacity, learning and self-organization capacities mediate the impact of follow-up supportive policy on livelihood perception, with self-organization capacity serving as both a primary driver and a mediating factor in influencing livelihood perception. Objective livelihood quality is primarily influenced positively by buffering capacity and adaptive strategies, with buffering capacity being the most important direct driver and mediating variable in determining livelihood quality.

-

(3)

Resettlement characteristics have a moderating effect on livelihood adaptation. Compared to short-term resettlement, mid-to-long-term resettlement shows a greater positive impact of follow-up supportive policy on learning capacity and a higher marginal contribution of learning capacity to adaptive strategies. Across different resettlement modes, follow-up supportive policy more significantly enhances the buffering capacity of village resettlement and shows a more positive synergistic effect on the livelihood perception of town resettlement.

Policy implication

Strengthening long-term capacity buildings

Reducing the loss of feasible capabilities and fostering long-term sustainable development capacity are essential to optimizing migrant livelihood systems into an “ideal” state.The significant changes brought by relocation make it challenging for farmers to shift to higher-skill occupations. Bridging the knowledge gap between migrants’ existing skills and labor market demands is therefore crucial. This can be addressed through targeted short-term skills training and long-term vocational education, which enhance household core competencies, enabling migrants actively adapt to changing environments and pursue alternative, diversified livelihoods. Furthermore, providing inclusive finance and microloans is necessary as a risk buffer for migrants, facilitating the transition in their production methods. Additionally, efforts should be made to strengthening organizational development and linkages to external resources, enhancing the heterogeneity and hierarchy of migrants’ social networks and expanding their access to social resources.

Enhancing sustainable income and reducing economic vulnerability

A significant improvement in economic conditions is essential for the full social integration of migrants and sustainable poverty alleviation. Local governments should prioritize creating stable and sufficient employment opportunities for resettled households and integrating them into public employment services. This can be achieved by promoting modern industries in ethnic regions, fostering community factories, upgrading poverty alleviation workshops, and encouraging flexible employment options that cater to migrants of various ages, genders, and skill levels. Additionally, it is crucial to protect the rights of relocated households by extending land contract rights, agricultural subsidies, and collective income entitlements, while increasing their share of land quota trading benefits to enhance property income. For town resettlements without land, transitional living subsidies should be provided to mitigate the financial risks posed by higher living costs and large expenditures. Finally, establishing a livelihood tracking system to monitor household income and expenditure during the transitional period will improve risk identification and enable timely interventions.

Fostering community governance and social integration

A strong sense of psychological identification and place attachment is crucial for migrants’ long-term and stable settlement, significantly contributing to both individual and community wellbeing27. Active involvement in local community building acts as a catalyst for migrants to gain recognition and develop attachment to their new environment45. Thus, it is vital to establish a community governance system based on shared participation and collaboration, gradually enabling migrants to engage in self-management and self-service. Strengthening both formal and informal structures is necessary, with a focus on encouraging them to participate in professional associations, cooperatives, and production organizations. Additionally, improving public spaces such as cultural squares and promoting ethnic cultural activities are key to addressing the diverse cultural needs of relocated households, fostering opportunities for interaction and communication. Besides, providing psychological support and social services to migrants is highly recommended to enhance their sense of belonging.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Transforming our World. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN, 2015).

Seth, S. & Tutor, M. V. Evaluation of anti-poverty programs’ impact on joint disadvantages: Insights from the Philippine experience. Rev. Income Wealth. 67(4), 977–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12504 (2021).

Zhang, L., Xie, L. Y. & Zheng, X. Y. Across a few prohibitive miles: The impact of the anti-poverty relocation program in China. J. Dev. Econ. 160, 102945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jdeveco.2022.102945 (2023).

Lo, K., Xue, L. & Wang, M. Spatial restructuring through poverty alleviation resettlement in rural China. J. Rural Stud. 47, 496–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.06.006 (2016).

ONCCP (Office of the National Committee for Central Planning). Ten Years Perspective Plan: 1984/85-1993/94. Addis Ababa. (1984).

Arnall, A. et al. Flooding, resettlement, and change in livelihoods: Evidence from rural Mozambique. Disasters 37(3), 468–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12003 (2013).

Finco, M. V. A. Poverty-environment trap: A non linear probit model applied to rural areas in the north of Brzail. Am-Euras J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 5(4), 533–539 (2009).

Zhou, Y. et al. Targeted poverty alleviation and land policy innovation: Some practice and policy implications from China. Land. Use Pol. 74, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.04.037 (2018).

Zhou, Y. & Liu, Y. The geography of poverty: Review and research prospects. J. Rural Stud. 93, 408–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.01.008 (2022).

Li, C. et al. The impact of the anti-poverty relocation and settlement program on rural households’ well-being and ecosystem dependence: Evidence from Western China, Soc. Natur. Resour. 34(1), 40–59 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920. 2020. 1728455.

Chen, Y., Tan, Y. & Gruschke, A. Rural vulnerability, migration, and relocation in mountain areas of Western China: An overview of key issues and policy interventions. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 19, 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjpre.2021.05.012 (2021).

Zhou, S. & Chen, S. The impact of the anti-poverty relocation and settlement program on farmers’ livelihood: Perspective of livelihood space. Sustainability 15, 8604. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118604 (2023).

Liu, Y. S., Liu, J. L. & Zhou, Y. Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies. J. Rural Stud. 52, 66–75. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j. jrurstud (2017). 2017.04.002.

Shi, P., Vanclay, F. & Yu, J. Post-resettlement support policies, psychological factors, and farmers’ homestead exit intention and behavior. Land 11, 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020237 (2022).

Rogers, S. & Wang, M. Environmental resettlement and social dis/re-articulation in Inner Mongolia. China Popult Environ. 28(1), 41–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-007-0033-x (2006).

Liu, W. et al. Exploring livelihood resilience and its impact on livelihood strategy in rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 150, 977–998 (2020a,). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02347-2

Zhu, Y. T. et al. Poverty alleviation relocation, fuelwood consumption and gender differences in human capital improvement. Int. J. Env Res. Pub He. 20(2), 1637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021637 (2023).

Liu, W., Li, J. & Xu, J. Impact of the ecological resettlement program in southern Shaanxi Province, China on households’ livelihood strategies. For. Policy Econ. 120 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2020.102310 (2020).

Leng, G. X., Feng, X. L. & Qiu, H. G. Income effects of poverty alleviation relocation program on rural farmers in China. J. Integr. Agric. 20(4), 891–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63583-3 (2021).

Li, C. et al. The impact on rural livelihoods and ecosystem services of a major relocation and settlement program: A case in Shaanxi, China. Ambio 47, 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-017-0941-7 (2018).

Chen, J. et al. Farmers’ livelihood adaptation to environmental change in an arid region: A case study of the Minqin Oasis, northwestern China. Ecol. Indic. 93, 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.05.017 (2018).

Rogers, S. et al. Moving millions to eliminate poverty: China’s rapidly evolving practice of poverty resettlement. Dev. Policy Rev. 38, 541–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12435 (2019).

Smit, B. & Wandel, J. Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Global Environ. Chang. 16(3), 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.03.008 (2006).

Pandey, V. P. et al. A framework to assess adaptive capacity of the water resources system in Nepalese river basins. Ecol. Indic. 11(2), 480–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2010.07.003 (2011).

Acosta, L. et al. A spatially explicit scenario-driven model of adaptive capacity to global change in Europe. Global Environ. Chang. 23(5), 1211–1224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.03.008 (2013).

Brooks, N., Adger, W. N. & Kelly, P. M. The determinants of vulnerability and adaptive capacity at the national level and the implications for adaptation. Global Environ. Chang. 15(2), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.12.006 (2005).

Zhu, D. M., Jia, Z. Y. & Zhou, Z. X. Place attachment in the Ex-situ poverty alleviation relocation: Evidence from different poverty alleviation migrant communities in Guizhou Province. China Sustain. Cities Soc. 75, 103355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103355 (2021).

Warrick, O. et al. The ‘Pacific adaptive capacity analysis framework’: Guiding the assessment of adaptive capacity in Pacific island communities. Reg. Environ. Change. 17, 1039–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-016-1036-x (2017).

DFID. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets. London: DFID Working Paper. (1999).

Nelson, D. R., Adger, W. N. & Brown, K. Adaptation to environmental change: Contributions of a resilience framework. Annu. Rev. Env Resour. 32(1), 395–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.32.051807.090348 (2007).

Engle, N. L. Adaptive capacity and its assessment. Global Environ. Chang 21. 647–656 (3011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.019

Grothmann, T. & Patt, A. Adaptive capacity and human congnition: the process of individual adaptation to climate change. Global Environ. Chang. 15, 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.01.002 (2005).

Ma, L. et al. Livelihood capitals and livelihood resilience: understanding the linkages in China’s government-led poverty alleviation resettlement. Habitat Int. 147, 103057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2024.103057 (2024).

Lo, K. & Wang, M. How voluntary is poverty alleviation resettlement in China? Habitat Int. 73, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.01.002 (2018).

Liu, M. Y., Yuan, L. & Zhao, Y. Risk of returning to multidimensional poverty and its influencing factors among relocated households for poverty alleviation in China. Agriculture 14, 954. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14060954 (2024).

World Bank. World Development Report 2000, 2001: Attacking Poverty (Oxford University Press, 2000).

Cernea, M. M. & Schmidt-Soltau, K. Poverty risks and national parks: Policy issues in conservation and resettlement. World Dev. 34, 1808–1830. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j. worlddev.2006.02.008 (2006).

Yang, Y. Y., Sherbinin, A. D. & Liu, Y. S. China’s poverty alleviation resettlement: Progress, problems and solutions. Habitat Int. 98, 102135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102135 (2020).

Speranza, C. I., Wiesmann, U. & Rist, S. An indicator framework for assessing livelihood resilience in the context of social ecological dynamics. Global Environ. Chang. 28(1), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.06.005 (2014).

Kim, D. H. The link between individual and organizational learning. Sloan. Manage. Rev. 35(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-9850-4.50006-3 (1993).

Carpenter, S. et al. From metaphor to measurement: Resilience of what to what? Ecosystems 4(8), 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-001-0045-9 (2001).

Liu, W. et al. Livelihood adaptive capacities and adaptation strategies of relocated households in rural China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6 https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.1067649 (2022).

Zhang, C. X. et al. Analysis of the evolvement of livelihood patterns of farm households relocated for poverty alleviation programs in ethnic minority areas of China. Agriculture 14, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14010094 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. Livelihood adaptation of rural households under Livelihood stress: evidence from Sichuan Province, China. Agriculture 11, 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11060506 (2021).

Feng, L. The path of social integration of migrants in poverty alleviation relocation: A case study of dongchuan from Yunnan plateau mountainous areas. J. Rural Stud. 110 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2024.103381 (2024).

Sina, D. et al. A conceptual framework for measuring livelihood resilience: Relocation experience from Aceh, Indonesia. World Dev. 117, 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.01.003 (2019).

Chin, W. W. & Marcoulides, G. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Adv. Hospitality Lsure. 295(2), 295–336 (1998).

Hanafiah, M. H. Formative vs. reflective measurement model: Guidelines for structural equation modeling research. Int. J. Anal. Appl. 18(5), 876–889. https://doi.org/10.28924/2291-8639-18-2020-876 (2020).

Jarvis, C. B., MacKenzie, S. B. & Podsakoff, P. M. A critical review of construct indicators and measurement model misspecification in marketing and consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 30(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1086/376806 (2003).

Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M. & Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares: The better approach to structural equation modeling? Long. Range Plann. 45(5-6), 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2012.09.011 (2012).

Bagozzi, R. P. Principles of Marketing Research (Blackwell, 1994).

Urbach, N. & Ahlemann, F. Structural equation modeling in information systems research using partial least squares. J. Inf. Technol. 11(2), 5–40 (2010).

Dowling, C. Appropriate audit support system use: The influence of auditor, audit team, and firm factors. Acc. Rev. 84(3), 771–810. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2009.84.3.771 (2009).

Diamantopoulos, A. The error term in formative measurement models: Interpretation and modeling implications. J. Model. Manag. 1(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465660610667775 (2006).

Bruhn, M., Georgi, D. & Hadwich, K. Customer equity management as formative second-order construct. J. Bus. Res. 61(12), 1292–1301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.016 (2008).

Tenenhaus, M. et al. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data an. 48(1), 159–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2004.03.005 (2005).

Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G. & Oppen, C. V. Using PLS path modelling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Quart. 33(1), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.2307/20650284 (2009).

Antwi-Agyei, P. et al. Adaptation opportunities and maladaptive outcomes in climate vulnerability hotspots of northern Ghana. Clim. Risk Manag. 19, 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2017.11.003 (2018).

Anton, C. E. & Lawrence, C. The relationship between place attachment, the theory of planned behaviour and residents’ response to place change. J. Environ. Psychol. 47, 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jenvp.2016.05.010 (2016).

Sargani, G. R. et al. Impacts of livelihood assets on adaptation strategies in response to climate change: evidence from Pakistan. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 25, 6117–6140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02296-5 (2022).

Collins, B. The view from the salad bowl: community place attachment in multiethnic Los Angeles. Cities 94, 256–274. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j. cities.2019.06.002 (2019).

Chantarat, S. & Barrett, C. B. Social network capital, economic mobility and poverty traps. J. Econ. Inequal. 10, 299–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-011-9164-5 (2012).

M´endez, M. L. & Otero, G. Neighbourhood conflicts, socio-spatial inequalities, and residential stigmatisation in Santiago. Chile. Cities 74, 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.11.005 (2018).

Li, E., Deng, Q. & Zhou, Y. Livelihood resilience and the generative mechanism of rural households out of poverty: An empirical analysis from Lankao County, Henan Province. China J. Rural Stud. 93, 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.01.005 (2019).

Feng, W. L. & Li, S. Z. Human capital or social capital? - study on the factors of social adaption of the migrants. Popul. Dev. 22(4), 2–9 (2016). (in Chinese).

Alam, G. M., Alam, K. & Mushtaq, S. Influence of institutional access and social capital on adaptation decision: Empirical evidence from hazard-prone rural households in Bangladesh. Ecol. Econ. 130, 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.07.012 (2016).

Ma, W. & Abdulai, A. Does cooperative membership improve household welfare? Evidence from apple farmers in China. Food Policy. 58, 94–102.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.12.002 (2016).

Amado, M. & Wall-Up Method for the regeneration of settlements and housing in the developing World. Sustain. Cities Soc. 41, 22–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.05.024 (2018).

Mastromarco, C. & Woitek, U. Public Infrastructure Investment and efficiency in Italian regions. J. Prod. Anal. 25(1-2), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-006-7127-9 (2006).

Hertel, T. & Zhai, F. Labor market distortions, rural–urban inequality and the opening of China’s economy. Econ. Model. 23(1), 76–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2005.08.004 (2006).

Wang, H. et al. Has the largest-scale poverty alleviation relocation in human history promoted urbanization? An empirical analysis from China. Appl. Econ. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2023.2277704 (2023).

Pan, Z. Y. et al. Community support as a driver for social integration in ex-situ poverty alleviation relocation communities: A case study in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11, 1206. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03650-w (2024).

Liu, W. et al. Rural households’ poverty and relocation and settlement: Evidence from Western China. Int. J. Env Res. Pub He. 16, 2609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142609 (2019).

Ranjan, R. Impact of COVID-19 on migrant labourers of India and China. Crit. Sociol. 47(4–5), 721–726. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920520975074 (2021).

Rogers, S. et al. China’s rapidly evolving practice of poverty resettlement: Moving millions to eliminate poverty. Dev. Policy Rev. 38, 541–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12435 (2020).

Gao, B. F., Li, C. & Li, S. Z. Follow-up supportive policy, resource endowments, and livelihood risks of anti-poverty relocated households: Evidence from Shaanxi Province. Econ. Geogr. 42(04), 168–177 (2022). (In Chinese).

Chambers, R. & Conway, G. Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. IDS discussion paper 296. London: Institute of Development Studies (1992).

Lu, H. G. et al. Impact of natural disaster shocks on farm household poverty vulnerability—A threshold effect based on livelihood resilience. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.860745 (2022).

Liu, W., Xu, J. & Li, J. Livelihood vulnerability of rural households under poverty alleviation relocation in southern Shaanxi China. Resour. Sci. 10(8), 2002–2014. https://doi.org/10.18402/resci.2018.10.09 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to the local governments of Liangshan Yi autonomous prefecture for providing valuable data and assisting in fieldwork, as well as all the families who participated in the investigation. Additionally, the authors would like to acknowledge the valuable feedback provided by the anonymous reviewers.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(Grant Number 42001173, 41901209, 41671152), Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education(Grant Number 20YJC790196, 24YJCZH383).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, X.Y. and X.Q.; methodology, T.H.; investigation, X.Y., X.Q. and T.H.; Writing-original draft preparation, X.Y. and F.Z.; writing- review and editing, X.Y., X.Q. and Y.X., visualization, X.Y. and T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, X., Qiu, X., Zhu, F. et al. Follow-up supportive policies and risk perception influence livelihood adaptation of anti-poverty relocated households in ethnic mountains of southwest China. Sci Rep 14, 30008 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81820-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81820-1