Abstract

Space debris around the Earth are becoming an increasing threat for space missions. Their number is growing due to the frequent launches of satellites from space agencies and private enterprises. This study examines simulated break-up events alongside actual samples of catastrophic events; we analyse the generated fragments with the objective of assigning them to clusters and classifying the debris based on their dynamical properties. We propose to accomplish these goals by performing the analysis using the so-called proper elements, which are quantities obtained by implementing perturbation theory to average the equations of motion over the angle variables. Subsequent to this filtering procedure, the proper elements enjoy the remarkable property to remain nearly constant over time. We find that proper elements are highly suitable for the analysis through machine learning methods with the purposes of clustering and classifying the fragments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The European Space Agency estimates that in the space around the Earth there are more than 54 000 objects of size larger than 10 cm and 140 millions of space debris with size between 1 mm and 1 cm1. Although having a small size, these objects can be extremely dangerous, due to their high velocity impact2,3. It is therefore of utmost importance to classify the debris and identify groups of fragments generated by a break-up event, on the basis of the dynamical properties of the fragments.

We contribute to investigate these issues by presenting results with a twofold aim. The first goal (G1) is to devise a procedure to identify clusters of debris, generated by satellites that underwent catastrophic events; this task will be achieved through unsupervised machine learning techniques. The second goal (G2) consists in classifying the fragments by introducing a quantity that allows one to keep track of the debris during their evolution; this task will be reached through a supervised classification method. The goals (G1) and (G2) complement each other and they both have important practical consequences: we can use the classification to follow each fragment in time and then use this information at any time to identify clusters in the orbital elements space; alternatively, we can first find clusters of fragments and then evolve backward in time to develop a debris archeology to infer past properties of the fragments. We emphasize that these goals enable to reconnect the debris to their source body and to keep track of the evolution of the fragments.

We will consider objects between 2000 and 36 000 km of altitude, namely outside the Low-Earth Objects (LEO) region, wherein the effect of the atmosphere must be taken into account. Objects situated beyond LEO will be described by a conservative dynamical system. Furthermore, objects that are not in close proximity to resonances will be considered, specifically those whose frequencies are not (nearly) commensurable with those associated to Earth, Moon and Sun.

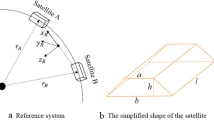

The methodology proposed in this study relies on the computation of dynamical quantities known as proper elements, which are the outcome of a mathematical computation based on the application of perturbation theory (see “Supplementary material”). They can be briefly introduced as follows. The dynamics of each fragment is characterised by the following set of variables: \((a,e,i,\ell ,\omega ,\Omega )\), where a is the semimajor axis, e the eccentricity, i the inclination, \(\ell\) the mean anomaly, \(\omega\) the argument of perigee, \(\Omega\) the longitude of the ascending node (and similarly for Moon and Sun). The variation in time of such quantities is obtained by integrating the equations of motion; outside LEO, these equations include the Keplerian term, the geopotential to account for the non-spherical form of the Earth (with expansions in spherical harmonics where only the most significant terms are retained), the gravitational influence of Moon and Sun (which are treated as third-body perturbations), and the Solar radiation pressure (hereafter SRP). The equations of motion including such contributions depend on the above sets of variables describing the dynamics of debris, Moon and Sun (see “Supplementary material”). Consequently, the equations of motion depend on angular variables that vary on different time scales: the mean motion of the debris and the sidereal time (describing the rotation of the Earth) vary over days, the mean anomalies of Moon and Sun vary, respectively, on periods of one month and one year, the arguments of perigee and the longitudes of the ascending nodes vary over periods of several years. The dependence on different time scales requires the implementation of a dedicated perturbation theory to remove the oscillations in time through a hierarchical procedure. According to which averaging is implemented, we obtain three distinct sets of elements. The osculating orbital elements, which are measured by astronomical observations or computed integrating the complete equations of motion (without any filtering). The other two sets of elements, called mean and proper elements, are determined through a two-steps procedure. (1) The mean elements are obtained integrating the equations of motion after filtering over the fast variables, precisely after averaging over the mean anomaly and the sidereal time. The proper elements are obtained implementing perturbation theory by averaging over all angle variables (see, e.g.,4); this step is achieved by determining a transformation of coordinates prescribed by a suitable generating function. (2) Mean and proper elements are back-transformed to the original variables, using the generating function to determine the inverse transformation of coordinates.

We will make substantial use of the property that proper elements are quasi-integrals of motion, namely they are nearly preserved under the evolution, since they have been obtained by removing the dependence on the angles. This property enhances the efficacy of proper elements for the dynamical characterisation of the fragments, either leading to the debris classification labeled by their proper elements or rather by using the proper elements to assign the fragments to clusters. We recall that proper elements were introduced in5 for the study of asteroids families and further developed in6,7,8,9 (see also references therein); more recently, proper elements for space debris have been investigated in10,11,12,13 (see also the pioneer work14). To achieve (G1), we rely on a procedure based on machine learning clustering methods, that allows one to group fragments after a break-up event (either simulated or real) on the basis of the information provided by mean and proper elements. Such procedure combines different ingredients: a simulator of break-up events (to get sample cases of collisions or explosions of satellites), perturbative methods (to compute the proper elements), measures of probability quantities (to predict whether the clustering procedure is reliable and successful), machine learning techniques (to identify clusters with similar dynamical properties). To obtain the goal (G2), we implement a supervised classification method, employing a small percentage of the data for training. We anticipate that clustering and classification methods give very effective results when accomplished through proper elements, due to their nearly-constancy property. We emphasize that the proposed procedures are based on a theoretical ground, which ensures robust methods to classify the debris and to allocate them in clusters.

Results

Clustering

The identification of clusters of fragments after a break-up event is investigated using two cases: simulated samples and a real test case.

Simulated samples

We propose a procedure consisting of several steps which are summarised in the flowchart of Fig. 1, each step being described below, together with a representative test case.

Synthetic data are obtained through the program SIMPRO15, which is a simulator of break-up events (either explosions or collisions) and a propagator of the orbits of the generated fragments16. The simulation of a catastrophic event is based on the model EVOLVE 4.0, developed in17,18. In case of explosions, the input data of the simulator are the orbital elements \((a,e,i,\ell ,\omega ,\Omega )\), the maximum size of the generated fragments and the type of parent body (e.g., Molniya satellite, Ukranian Tsyklan, Titan Transtage); in case of collisions, the type of parent body is different than that for explosions (for example, upper stage or spacecraft) and one needs to provide the mass of the parent body, the mass of the impact projectile, and the collision velocity.

Datasets \(\mathcal {D}_M\) and \(\mathcal {D}_P\)

We consider explosions of two or three satellites (either of the same or different type), generating an overall number of fragments varying between 150 and 200. The fragments after the break-up event have different velocities, but the same position as the parent body at the time of break-up. For each fragment, we transform the Cartesian state vector to the orbital elements, we compute their mean elements, which coincide with the osculating elements filtered over small oscillations, and we let them evolve in time (usually up to 20 years).

Considering that in practical situations the elements of the fragments may not be consistently available at all times, we construct our test datasets (\(\mathcal {D}_M\)) so that each fragment is stored at random times. To simulate realistic scenarios where the information pertaining to the fragments deteriorates over time, we control the shuffling process by specifying the observable times as values of a \(\chi ^2\) distribution with 2 degrees of freedom. Results for a test case are described in Fig. 2, which gives a) the initial distribution in (a, e, i) after the break-up of two satellites, b) the distribution of the fragments at a controlled shuffled time, representing our dataset \(\mathcal {D}_M\), with different colours to distinguish the two groups and without colours as in c).

(a) The distribution in (a, e, i) at the initial time of two groups of fragments generated by the break-up of two satellites. (b) The distribution of the same groups choosing each fragment at a controlled shuffled time. (c) Same as (b), but without colours. (d) DBSCAN correctly provides two clusters, shown in the projected plane (e, i), when using proper elements at shuffled times. (e) DBSCAN erroneously provides three clusters, projected in the plane (e, i), when using mean elements at shuffled times.

Subsequently, for each fragment within \(\mathcal {D}_M\) we compute the proper elements to construct the set \(\mathcal {D}_P\). Proper elements are obtained through a procedure based on perturbation theory (see “Supplementary material”). In short, after averaging over the fast variables, one expands the Hamiltonian around reference values for the eccentricity and the inclination. A normal form is implemented on the expanded Hamiltonian to remove, up to a given order, the dependence on all angle variables. This is obtained by constructing a canonical change of coordinates by using a suitable generating function. The resulting generating function is then used to obtain the proper elements by back-transforming to the original variables through the inverse canonical transformation.

Clustering the fragments

We apply a machine learning technique to reconstruct groups of fragments, based on data from \(\mathcal {D}_M\) and \(\mathcal {D}_P\). We privilege an unsupervised clustering method that does not need in input the number of clusters. In particular, we choose DBSCAN, which is common in many platforms and easy to implement; in19 we also made comparisons with other unsupervised and semi-supervised methods, e.g. Kmeans or GaussianMixture. Our goal is to cluster fragments by assigning them to different groups, which means to find a map from the features (a, e, i) of each fragment to categories, based on the distribution of the dataset in the space of features.

A comparison between the results obtained clustering mean or proper elements for a test case is given in Fig. 2 plots d) and e), which show the clusters projected on the (e, i)-plane. The colours serve to differentiate the resulting groups: (erroneously) three groups for mean elements and (accurately) two groups for proper elements. Given that proper elements are quasi-constants of motion, clustering exhibits enhanced performance when utilizing proper elements as opposed to mean elements, as evidenced by the ensuing result. As the dataset is simulated, the initial grouping is known a priori; hence, we can define the accuracy as the number of correctly classified objects divided by the total number of instances. According to this definition, in the example of Fig. 2 the accuracy is 0.92 for mean elements and 1 for proper elements (which represents the maximum accuracy).

Clustering along the evolution of mean and proper elements

To leverage the dynamical properties of the proper elements, the evolution of both proper and mean elements is computed. For each element in \(\mathcal {D}_M\) and \(\mathcal {D}_P\), we determine the evolution over a period of 40 years (20 years backward and 20 years forward); this leads to define new datasets \(\{\mathcal {D}_M^i\}\) and \(\{\mathcal {D}_P^i\}\) which contain the evolution of mean and proper elements, respectively, recorded every 6 months.

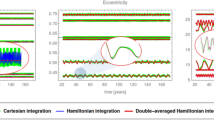

It is essential to consider that the evolution of the elements might experience fluctuations. As a consequence, a critical information is whether mean and/or proper elements spread in time; this implies that the elements at the final time may significantly differ from those at the initial time, and possibly that the elements of all fragments do not maintain the same configuration observed initially. To evaluate whether the distribution of fragments undergoes temporal modifications, an estimation of the probability density function (PDF) for the inclinations is computed, followed by the construction of a smooth histogram utilizing a kernel density estimation method. In Fig. 3, panel a) represents the initial distribution of the fragments, while panel b) shows the evolution of mean and proper elements over a period of 40 years. For this test case, and for all samples we considered, we noticed that the PDFs of the mean elements vary in time, while those of the proper elements are nearly constant as shown in Fig. 3, panel c).

(a) Initial distribution of all fragments in mean elements. (b) Evolution (in lighter colours) of the two groups (purple and green) in the mean (light) and proper (darker) colours for a period of 40 years. (c) The evolution of the estimated PDF in inclination over 40 years in mean (orange) and proper (blue) elements. (d) The evolution of the accuracy of DBSCAN for mean (orange) and proper (blue) elements.

As a recommended guideline, to effectively implement the clustering method, it is advisable to apply the procedure to cases where the proper elements do not experience significant deviations throughout the evolutionary process. Furthermore, clustering methods typically rely on the analysis of the distances among the orbital elements (a, e, i) of the fragments. The default distance is the Euclidean one; however, for large eccentricities, say bigger than 0.1, it is convenient to adopt the following distance among the elements \((a_j,e_j,i_j)\), \(j=1,2\), of two groups:

The modification induced by the choice of the distance (2.1) while using DBSCAN (or other methods) is significant, since (2.1) measures the distances at perigee; as a consequence, the clustering method inherits a dynamical information which contributes to improve its performance. We compute the performance of DBSCAN for the datasets \(\{\mathcal {D}_M^i\}\) and \(\{\mathcal {D}_P^i\}\); the accuracy obtained clustering the fragments using mean and proper elements is given in panel d) of Fig. 3, which shows a remarkable high average value equal to 0.994 for proper elements, and a lower average value of 0.63 for mean elements.

Real test case

A real sample case is considered to test our procedure; the data of the fragments are taken from SpaceTrack20. These data allow us to compute the initial mean and proper elements, that we propagate up to a final time equal to \(t=20\) years.

We consider the satellites SATCOM 3 (which failed reaching the geosynchronous orbit upon its launch in 1979) and ATLAS 5 CENTAUR R/B (which was used to deliver the GOES 17 satellite into orbit on 2018).

The available data of the generated debris consist in, respectively, 15 and 134 fragments; their orbital elements are located around \(28\,000\) km for the semimajor axis, 0.45 for the eccentricity and between 6 and 14 degrees for the inclination. The groups of fragments are shown in panel a) of Fig. 4. Under the evolution, the proper elements of the two groups of fragments are nearly constant, while the mean elements experience fluctuations, observed over 20 years, which are moderate in eccentricity and larger in inclination (see Fig. 4, panel b)). We compute the evolution of mean and proper elements, storing the results at 40 different times with time-step equal to 6 months. Panel c) of Fig. 4 shows the PDF in inclination of the fragments of both groups in mean and proper elements.

(a) Initial distribution of the fragments from SATCOM 3 and ATLAS 5 CENTAUR R/B in mean elements (a, e, i). (b) Evolution of mean elements (orange) and proper elements (blue) for both groups of fragments in the \(e-i\) plane. (c) The evolution of the estimated PDF in inclination over 20 years in mean (orange) and proper (blue) elements. (d) Accuracy over time of DBSCAN for mean (orange) and proper (blue) elements (using the same set of parameters).

For most of the times, DBSCAN correctly finds 2 clusters when analysing the data corresponding to the proper elements. The accuracy in proper elements averaged over all times up to 20 years is about 0.948, which provides a better performance with respect to the mean elements whose average accuracy is about equal to 0.731. At the onset of the evolutionary process, the precision of clustering based on mean elements surpasses that achieved through the use of proper elements, which aligns with expectations in practical scenarios. However, the comprehensive results of the procedure indicate a considerable benefit in employing proper elements over extended durations, as shown in panel d) of Fig. 4.

The inadequacy of clustering via mean elements is principally attributable to the substantial fluctuations observed in the evolution of the mean inclination. As shown in panel c) of Fig. 4, the estimated PDF for the inclination changes significantly over 20 years when we analyse the mean elements, while it remains almost constant when we consider the proper elements.

Classification of the fragments

In light of multiple, generally two or three, nearby break-up events, this study examines methodologies for the classification of the generated fragments. To reproduce a realistic scenario, we assume to know the early structure of the break-up events and we seek to classify each newly observed object in the proximity of these catastrophic occurrences. We analyze our experiment in two scenarios: (i) using a sample of the data just after the break-up to train the classifier and test it for the full dataset at any time; (ii) using a sample of controlled shuffled data to train the classifier and test it at any time. We do not focus here on different classification methods or on the parameters tuning, but rather on the difference of the results when classifying through mean or proper datasets. We define our classifier by using the Support Vector Machine (SVM) methodFootnote 1 and keep the split thresholds fixed at \(5\%\) (when analysing 2 groups) and \(15\%\) (when analysing 3 groups); this choice reproduces a real situation in which we might have limited information. We validate the predicted classes with the actual classes known a priori, and we define the accuracy as the ratio between the number of correct predictions and the total number of predictions.

We present the results of the experiments in Fig. 5, which contains the confusion matrices of the training-testing process and the evolution in time of the accuracy. We consider two examples composed by 2 and 3 groups of fragments.

The mean elements might give better results close to the break-up time; however, the accuracy of their prediction decreases with time. Conversely, even using a small amount of data, the proper elements are always close to full accuracy, either when training close to break-up time or at shuffled times.

(a) Analysis of 2 groups: training the classifier close to break-up and (b) at shuffled times. (c) Analysis of 3 groups: training the classifier close to break-up and (d) at shuffled times. The panels provide the confusion matrices at the training time and the evolution of the accuracy recorded every 6 months up to 20 years for (a), (b) and up to 30 years for (c), (d).

Discussion

The tasks of clustering (goal G1) and classifying (goal G2) fragments produced by an explosion or collision of satellites are of critical importance. This is particularly pertinent in light of the increasing number of satellites currently in orbit, which consequently elevates the probability of break-up events.

The procedure proposed in this work to cluster and classify space debris relies on the mathematical construction of quantities that, at all effects, act as fingerprints of the fragments generated by the catastrophic event. The proposed approach is based on the rigorous determination of the proper elements, whose nearly-invariance over time, as it can be proved by implementing perturbation theory, guarantees a theoretical control of the procedure.

The computation of the proper elements leads to identify clusters of fragments formed by homogeneous elements that exhibit similar orbital characteristics, in particular in terms of semimajor axis, eccentricity and inclination. To identify the clusters, we have used DBSCAN, an unsupervised machine learning method. A crucial point for the success of the method is to combine it with information about the dynamics; this task has been achieved by replacing the standard (Euclidean) distance by a user-defined quantity that takes into account the distance at perigee. Classifying fragments at any time is another important goal when studying space debris. Also this task is successfully accomplished using proper elements, even starting from a small fraction of known fragments at the break-up time. Both objectives have practical relevance: clustering allows one to separate the fragments and to form groups of debris, each one connected to a given parent satellite; classifying assigns the fragments to specific groups.

According to the analysis performed on our set of experiments, clustering and classifying through proper elements is successful whenever (i) the proper elements do not experience large excursions over time and (ii) whenever the initial groups of fragments do not have a strong overlap in terms of the orbital elements, namely semimajor axis, eccentricity, and inclination (see also19).

When conditions (i) and/or (ii) are violated, then the procedure might fail, since the elements of the fragments are mixed from the break-up time and therefore they can hardly be classified or attributed to different clusters. This is an inevitable consequence of the fact that the failure of condition (i) implies that the proper elements are not signatures of the dynamics, so that their use might not be a big improvement with respect to the mean elements; on the other hand, the failure of condition (ii) implies that the parent satellites are indistinguishable in terms of orbital elements; hence, they generate too many nearby fragments to allow for their separation, just on the basis of their dynamical characteristics.

The potentiality of the described procedures for clustering and classifying space debris extends well beyond the cases analysed in the current work, where we investigated regions which are governed by a conservative dynamical system and with initial conditions far from resonances. To have a more comprehensive overview, two main lines of research will be further addressed. On one side, we intend to proceed to analyse fragments that orbit close to resonances21, either tesseral resonances (hence, with frequency commensurable with the Earth’s rotational period) or lunisolar resonances (with frequency commensurable with the rates of variation of the angles describing the geometry of the orbits of Moon and Sun). This goal requires the implementation of a resonant normal form for the computation of the proper elements. If successful, it could give information on clustering debris generated by resonant objects, like Geostationary and GPS satellites. On the other side, we intend to investigate the behaviour of the quasi-integrals for satellites orbiting in LEO, namely in the region where the dynamics is affected by the atmospheric drag; this region is characterised by a constant economic growth, due to the large number of satellites placed in LEO orbits by space agencies, academies, and commercial providers. The exploitation of proper elements in LEO requires a dedicated development of a normal form, which includes a dissipative effect22. These extensions exhibit significant potential and possess practical utility, attributable to the substantial number of satellites positioned in resonant orbits or operating at low altitudes.

Data availability

Data and relevant programs are available on GitHub at

https://github.com/VTudor95/clustering_classifying_space_debris.

Notes

We have tested as well other methods (Random Forests, Naive Bayes etc.), but we did not notice big differences with SVM.

References

ESA web site: https://www.esa.int/Space_Safety/Space_Debris/Space_debris_by_the_numbers

Kessler, D. J. & Su, S.-Y. Contribution of explosion and future collision fragments to the orbital debris environment. Adv. Space Res. 5(2), 25–34 (1985).

Klinkrad, H. Space debris: Models and risk analysis (Springer-Praxis, Berlin-Heidelberg, 2006).

Efthymiopoulos, C. Canonical perturbation theory, stability and diffusion in Hamiltonian systems: Applications in dynamical astronomy. Workshop Ser. Asociacion Argentina de Astronomia 3, 3–146 (2011).

Hirayama, K. Groups of asteroids probably of common origin. Astron. J. 31, 185–188 (1918).

Kozai, Y. The dynamical evolution of the Hirayama family, in: “Asteroids” (T. Gehrels, Ed.), Univ. Arizona Press, pp. 334-35 (1979)

Knežević, Z. & Milani, A. Are the analytical proper elements of asteroids still needed?. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 131, 27 (2019).

Lemaitre, A. Proper elements: What are they?. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 56, 103–119 (1992).

Milani, A. & Knežević, Z. Secular perturbation theory and computation of asteroid proper elements. Cel. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 49, 347–411 (1990).

Celletti, A., Pucacco, G. & Vartolomei, T. Proper elements for space debris. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 134, 11 (2022).

Celletti, A., Pucacco, G. & Vartolomei, T. Reconnecting groups of space debris to their parent body through proper elements. Sci. Rep. 11, 22676 (2021).

Celletti, A. & Vartolomei, T. Old perturbative methods for a new problem in Celestial Mechanics: The space debris dynamics. Bollettino Unione Matematica Italiana 16, 411–428 (2023).

Wu, D., & Rosengren, A.J. RSO proper elements for space situational and domain awareness, in “Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Technologies Conference AMOS” (2021)

Cook, G. E. Luni-solar perturbations of the orbit of an earth satellite. Geophys. J 6, 271–291 (1962).

SIMPRO executable version available at https://github.com/simproproject/simpro_app

Apetrii, M., Celletti, A., Efthymiopoulos, E., Galeş, C. & Vartolomei, T. Simulating a breakup event and propagating the orbits of space debris. Cel. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 136, 35 (2024).

AAVV, NASA Standard Breakup Model 1998 Revision, prepared by Lockheed Martin Space Mission Systems & Services for NASA, (1998).

Johnson, N. L., Krisko, P. H., Liou, J.-C. & Am-Meador, P. D. NASA’s new break-up model of EVOLVE 4.0. Adv. Space Res. 28(9), 1377–1384 (2001).

Celletti, A. & Vartolomei, T. Clustering space debris using perturbation theory, Preprint (2025)

SpaceTrack website: https://www.space-track.org

Rossi, A. Resonant dynamics of medium earth orbits: Space debris issues. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astr. 100, 267–286 (2008).

Celletti, A. & Galeş, C. Dynamics of resonances and equilibria of low earth objects. SIAM J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 17, 203–235 (2018).

Funding

T.V. acknowledges the support of “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University of Iasi, within the Research Grants program, Grant UAIC, code GI-UAIC-2023-02.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C. and T.V. contributed equally to all phases of preparation of the article. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Celletti, A., Vartolomei, T. A dynamics based procedure for clustering and classifying space debris. Sci Rep 15, 17925 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02434-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02434-9