Abstract

Multiple Osteochondromas (MO) can significantly impact physical functioning, yet evidence on how MO affects physical activity levels (PAL) and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) remains limited. This study aimed to: (1) characterize the PAL and physical and mental HRQOL of adult patients with MO and compare them with healthy subjects (2) explore whether illness-related symptoms, sociodemographic and psychological factors are associated with patients’ PAL and HRQOL. This cross-sectional study used a survey consisting of sociodemographic data and validated questionnaires on the PAL (Baecke Physical Activity Questionnaire) and HRQOL (SF-36). The PAL, physical and mental HRQOL were compared with reference scores of healthy subjects using a one-sample t-test. An a-priori defined theoretical framework (ICF-model) was used to select explanatory variables, including several psychological factors, for the multiple linear regression models of the dependent variables PAL and HRQOL. 342 patients (42.6% males) with a mean age of 41.8 ± 16.3 completed the survey. Mean PAL scores were 7.2 ± 1.7, physical HRQOL 41.7 ± 11.1 and mental HRQOL 49.1 ± 10.5. Except for mental HRQOL, these scores were lower than healthy subjects (p < 0.001). The final regression model for the PAL contained six factors (R2 = 0.221, p < 0.001) showing the strongest association with having a job and malignant degeneration. Fourteen variables, including pain-related disability and number of surgical procedures, explained physical HRQOL (R2 = 0.731, p < 0.001). For mental HRQOL, eight factors remained in the model (R2 = 0.618, p < 0.001) with anxiety explaining the most unique variance (9.4%). MO patients reported significantly lower PAL and physical HRQOL than healthy controls. This study provides insight in several factors associated with the PAL and HRQOL in MO which could be used to optimize patients’ treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple Osteochondromas (MO), or Hereditary Multiple Exostoses (HME), is a rare autosomal dominant inherited skeletal disorder characterized by multiple benign bone tumors, typically developing at the metaphysis of long bones and axial skeleton1,2. Its prevalence in Western countries has been estimated at 1:50,000. in previous literature2,3, with an equal distribution between genders4. Osteochondromas in MO can cause various complications such as compression on surrounding blood vessels, peripheral nerves and muscles, interference with growth, reduced mobility, and pain. Malignant degeneration of osteochondromas has been reported in 9.3% of patients aged 16 and older5. Approximately 66–88% of the patients will undergo at least one surgical procedure because of this disorder2,3,6.

Literature to date has mainly focused on the origin of MO, surgical procedures or specification of deformities1,3,7. Only a few studies focused on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) issues, activity limitations, or perceived symptoms associated with MO3,8,9. Patients with MO have reported lower HRQOL compared to the general population3,8. In other chronic conditions, various sociodemographic factors (comorbidities10, gender10,11,12, age, educational level10,11,12,13, BMI11,12, relationship status14, illness-related (pain and fatigue intensity11,12,13,15,16,17,18) and psychological factors (fear-avoidance beliefs, pain catastrophizing, depression, anxiety)11,13,15,17,18 are associated with patients’ perceived physical disability, physical activity level (PAL) and HRQOL. To our knowledge, only prevalence of pain and fatigue was investigated in patients with MO, with pain being reported by 76–95%6,16,19 and severe fatigue by 71%19.

Preceding literature on gender differences in HRQOL of MO-patients has presented contradicting findings. The study of D’Ambrosi et al.9 found that particularly female patients have a lower physical HRQOL, whereas other studies could not find differences between females and males7,14. More research is necessary to determine the role of gender in MO. No studies were identified that specifically explored sociodemographic, illness-related or psychological determinants of HRQOL in patients with MO. The lack of insight into psychosocial symptoms and their potential impact on HRQOL underscores the need for additional studies in this population.

Activity limitations, defined by International Classification of Functioning, disability and health (ICF) as difficulties in executing activities20, have been reported as a consequence of chronic pain; 26–56% of the MO-patients experienced problems during occupation3,8 and 7% was unable to work6. Patients also reported occupational problems due to pain with a great impact on QOL and negative effect of other MO-related problems on participation in sports3. However, no studies to date evaluated PAL in MO, defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles resulting in energy expenditure21. Physical activity is an important lifestyle factor in the prevention of major non-communicable disease and premature mortality22, but also reduces psychological burden and enhances overall well-being23.

In healthy controls and various other chronic conditions, a higher PAL was found to be associated with a higher HRQOL11,24,25. The directionality and strength of these associations can differ depending on the patient population, emphasizing the need to explore these factors in each specific chronic condition.

Given these knowledge gaps in MO, the present study aims to characterize patients’ PAL, HRQOL and to explore whether illness-related symptoms, sociodemographic or psychological factors are associated with patients’ PAL and HRQOL.

Based on previous research findings five hypotheses were formulated:

-

(1)

patients with MO have a lower HRQOL and PAL than healthy controls.

-

(2)

a higher PAL, after controlling for other factors, is significantly associated with a higher HRQOL in patients with MO.

-

(3)

higher BMI, higher pain and fatigue, and presence of psychological factors are negatively associated with the PAL.

-

(4)

female gender, higher BMI, comorbidity, higher pain and fatigue, physical disability and presence of psychological factors are negatively associated with physical HRQOL.

-

(5)

female gender, being single, a lower educational level, malignancy, more surgical interventions, higher intensity level of pain and fatigue, and presence of psychological factors are negatively associated with mental HRQOL.

Methods

Study design and patients

This cross-sectional study was performed in the Netherlands between May 2018 and December 2019 using an online survey. Adult Dutch-speaking patients diagnosed with MO, who were treated at the orthopedic outpatient clinic of the national HME-MO-expertise center (OLVG, Amsterdam) and members of the Dutch Patient Association ‘HME-MO Vereniging Nederland’, were invited to participate. Patients were recruited during their outpatient clinic visit or contacted by telephone. Members of the Dutch Patient Association could contact the coordinating researcher (IA) for more information by telephone or email via contact information provided through an online post on the Patient Association’s website. If interested, a patient information letter and informed consent form were sent by post or e-mail. This study was reported according to the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) guidelines, see Appendix 226.

Data collection

After providing informed consent, patients received a secure link by e-mail granting access to a digital questionnaire in Castor, Electronic Data Capture27. If patients had no access to the internet or a computer, a paper survey was sent by post. The survey consisted of a sociodemographic section and validated Dutch questionnaires regarding physical activity, quality of life, pain, fatigue and psychosocial factors.

Primary outcomes (dependent variables)

The physical activity level was measured with the Baecke Physical Activity Questionnaire (BPAQ), which was validated in a Dutch population28. The total score ranges from 3 to 15 and a higher score indicates a higher level of physical activity.

Health-related quality of life was measured with the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36 (SF-36)29,30. The physical component (SF-36 PCS) and mental component scores (SF-36 MCS) were calculated according to their specific instructions29,30. Subscale scores range from 0 to 100 and a higher score indicates higher levels of well-being and lower bodily pain29,31.

The BPAQ and SF-36 scores were compared to reference scores of the Dutch general population28,29.

Explanatory (independent) variables

Sociodemographic information as listed in Table 1 was collected. Pain was assessed using an 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS) for the patient’s average pain severity during the previous week. A higher score indicates greater pain severity, ranging from 0 to 1032. The Pain Disability Index (PDI) was used to measure for the interference of average pain complaints on functioning33. Scores range from 0 to 70, with higher values indicating greater interference. The Douleur Neuropathique en 4 Questions (DN4) was used for neuropathic pain. The DN4 consists of two parts, a questionnaire assessing pain characteristics and symptoms of abnormal sensations, and a clinical examination34. In this study, only the questionnaire was used, where a score of 4 or above (range 0–7) indicates neuropathic pain34.

Fatigue measures included an 11-point NRS for the patient’s average fatigue severity of the previous week, with a higher score indicating higher severity35. The Checklist Individual Strength (CIS) measures four areas of fatigue: fatigue severity, concentration, motivation and activity36. In this study, the total score of the CIS was used, ranging from 20 to 140, with higher scores indicating greater fatigue36.

Included psychological factors were anxiety and depression complaints measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) where higher scores indicate more severe symptoms (range 0–21)37,38. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) measures patients’ catastrophizing thoughts and feelings related to pain39. The total score ranges from 0 to 52, with higher values indicating greater catastrophizing40. Fear-avoidance beliefs regarding physical and work-related activities were measured with the Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ). Scores range from 0 to 96, with higher scores reflecting stronger avoidance beliefs41.

Further details on the assessments are available in Appendix 1 (supplemental material).

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed in SPSS version 27 for Windows (SPSS Inc. Headquarters, 233 s. Wacker Drive, 11th floor, Chicago, Illinois 60606, USA). The online survey had minimal risk of missing data because the digital software prevented patients from skipping a question. Patients who received a paper survey were contacted by telephone in case of missing items and the missing data were handled according to the questionnaire’s specific instructions, if available30. Due to insufficient available data, an a priori power calculation was not performed. The aim was to include a convenience sample of at least 300 adults, based on prevalence numbers of MO in the Netherlands42 and the findings from Goud et al. in their Dutch cohort study3.

Literature suggests a prevalence rate for MO of approximately 1 in 50,000 in Western populations2, while others have implied a higher rate3. Given the country’s population of 17 million, this estimate implies at least 340 affected individuals. Enrolling at least 300 adult patients and adhering to the rule of thumb of 10–15 participants per variable in linear regression modeling was intended to provide sufficient statistical power. Due to ambiguity regarding gender differences in patients with MO, descriptive data were compared between genders with a Chi-square test or independent samples t-test.

A one-sample t-test was performed to compare the normally distributed PAL (BPAQ) and HRQOL (SF-36) data of MO patients, respectively, with the reference score obtained from previous literature studies28,29. Patients were matched to reference scores based on gender only.

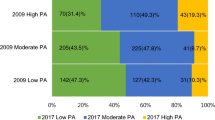

For the multiple linear regression models, purposeful selection of explanatory variables was performed in two steps. First, explanatory variables for all separate dependent variables (PAL, SF-36 PCS, and SF-36 MCS) were selected a priori based on a theoretical foundation i.e., the ICF model, and previous research findings on significantly associated sociodemographic, illness-related and psychological factors11,12,14,15,17,20,42 (Fig. 1).

ICF model of the a priori selected explanatory variables for the dependent variables: the physical activity level (BPAQ) and physical and mental health-related quality of life (SF-36). aWere not included in the regression model with the physical activity level (BPAQ) as dependent variable. The PDI measures disability at the activities level, equal to the ICF-level of the BPAQ. HRQOL, measured at the participation level, is assumed to be affected by the activities level and not the other way around. Abbreviations: DN4 douleur neuropathique en 4 questions, NRS numeric rating scale, CIS checklist individual strength, PDI pain disability index, PCS pain catastrophizing scale, SF-36 short form-36, BPAQ Baecke Physical Activity Questionnaire, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, FABQ Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, BMI Body Mass Index.

Second, a priori selected explanatory variables associated with the dependent variable in univariate regression analyses at a significance level of p ≤ 0.25 were added to the regression model. Multicollinearity was checked for each full multiple regression model (variance inflation factor (VIF) < 10)43. Then, a backward multiple linear regression analysis was performed with the significance level set at p ≤ 0.05. Normality of residuals and homoscedasticity were checked for the final models. Additionally, we report the squared semi-partial correlation (sr2) for each independent variable in the final model. The sr2 value indicates the unique proportion of variance in the outcome explained by that specific variable after accounting for the shared variance with other variables, thereby illustrating the independent contribution of each variable to the model.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patients’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. A total of 342 adults with MO completed the survey. Comorbidities and neuropathic pain (DN4) were reported significantly more often by women than by men. Female patients experienced a higher pain intensity than male patients (Mean Difference, MD = 1.12; 95% CI [0.58, 1.66]), more pain-related disability (MD = 6.12; 95% CI [2.98, 9.26]), greater fatigue on both the NRS (MD = 1.33; 95% CI [0.8, 1.86]) and the CIS (MD = 3.53; 95% CI [0.24, 6.8]), a higher level of anxiety (MD = 1.51; 95% CI [0.68, 2.34]), and a lower physical HRQOL (MD = 4.98; 95% CI [2.66, 7.3]).

Physical activity and health related quality of life in comparison to reference scores

Patients with MO reported a significantly lower mean PAL and physical HRQOL, but not mean mental HRQOL compared to reference scores of healthy, gender-matched subjects (Table 2).

Associations with the physical activity level

Table 3 presents the final regression model of PAL of patients with MO. A total of six factors remained in the model, explaining 22.1% of the total variance. The unstandardized ß shows that patients with a paid job have a 0.843 point higher PAL compared to those without a paid job. Additionally, patients who experienced more anxiety had a slightly higher PAL; for each point increase in HADS anxiety score, the BPAQ increases by merely 0.06. Malignant degeneration of an osteochondroma in the past, experiencing more pain, more depressive feelings and a higher BMI are negatively associated with patients’ PAL. Malignant degeneration of an osteochondroma has the second strongest association with patients’ PAL, reducing the BPAQ by 0.822. Having a paid job explains the highest unique variance (4.5%), followed by the experience of pain (2.9%) and depressive symptoms (2.2%).

Associations with physical health-related quality of life

The final regression model for physical HRQOL is presented in Table 4. A total of 14 variables remained in the final model explaining 73.1% of the total variance. Higher anxiety levels and completion of secondary or tertiary education, compared to primary education, were associated with a better HRQOL, while all other factors were associated with a worse HRQOL. Pain-related disability explained the most unique variance (4.8%), followed by anxiety (1.8%) and age (1.3%).

Associations with mental health-related quality of life

Table 5 presents the final regression model of mental HRQOL. Eight factors remained in the model, explaining 61.8% of the total variance. Having a paid job, older age and greater pain-related disability were associated with a slightly better mental HRQOL. Higher levels of depression, anxiety and fatigue (NRS) were associated with a worse HRQOL. Patients who completed secondary or tertiary education had a lower mental HRQOL by at least 4.9 points compared to those who completed only primary education. Anxiety explained the most unique variance (9.4%), followed by depression (4.6%) and fatigue (2.5%).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale study on PAL and HRQOL of patients with MO that also provides insight into associated sociodemographic, illness-related and psychological factors. Our findings suggest that patients with MO experience significantly lower PAL and reduced physical HRQOL—compared to gender-matched healthy controls—while reporting similar mental HRQOL. An association between PAL and HRQOL could not be confirmed in our study population. However, several patient characteristics and psychological factors were associated with PAL and HRQOL in this study—many of which are clinically modifiable and may serve as targets for future interventions. Below, we discuss these findings in relation to our five pre-specified hypotheses.

Hypothesis (1): patients with MO have a lower HRQOL and PAL than healthy controls.

Patients with MO have a significantly lower PAL and physical HRQOL than gender-matched healthy subjects, but similar mental HRQOL. A minimal clinical important difference (MCID) of 2.5–5 points for physical HRQOL of patients with rheumatoid arthritis has been reported44, meaning that the lower physical HRQOL (> 5 points) for both men and women with MO compared to healthy subjects can be interpreted as a clinically worse state. To the best of our knowledge, the MCID of the BPAQ has not yet been reported in patients with musculoskeletal complaints, underscoring the need for future research.

Hypothesis (2): a higher PAL, after controlling for other factors, is significantly associated with a higher HRQOL in patients with MO.

A positive relationship between the PAL and HRQOL in MO could not be confirmed. While this contrasts with some prior findings in chronic musculoskeletal populations25, it is plausible that other clinical or psychological factors mediate or moderate this relationship in MO. One likely explanation is the heterogeneity of disease severity and functional limitations; in those with severe skeletal deformities and restricted joint motion, increased physical activity may not translate into functional gains or improved HRQOL. Further studies are needed to better understand the impact of disease severity in MO on the association between PAL and HRQOL.

Hypothesis (3): a higher BMI, higher pain and fatigue, and presence of psychological factors are negatively associated with the PAL.

The negative relationship between PAL and higher BMI, pain intensity, and depressive symptoms in MO-patients has been confirmed and is in accordance with other populations45,46. A longitudinal study on the reciprocal relationship between physical activity and depression showed that performing moderate to vigorous physical activity at least once a week is associated with lower depressed mood45. This should be targeted in the treatment plans of MO-patients. Patients’ PAL is positively associated with having a paid job and these patients had, besides a higher work-index, also a significantly higher PAL sport-, and leisure-index (p < 0.001) than patients who did not have a paid job. Being able to work seems an important contributor to patients’ PAL. More anxiety was also related to a higher PAL, while in contrast previous studies reported that lower levels of anxiety were related to higher levels of physical activity46,47. However, anxiety only contributes 1% of the total explained variance, which is rather negligible, and only 11.7% of the total patient sample has scores above the cut-off score (> 7) for anxiety37. Patients who experienced malignant degeneration of an osteochondroma into a chondrosarcoma in the past had a significantly lower PAL. These results are in line with findings on activity limitations after bone cancer48.

Hypothesis (4): female gender, higher BMI, comorbidity, higher pain and fatigue, physical disability and presence of psychological factors are negatively associated with physical HRQOL.

Our study confirmed this hypothesis for all factors except female gender. Ambiguity exists on whether MO affects men and women differently3,8,9. We hypothesized that female gender would be negatively associated with PAL and physical and mental HRQOL, but gender was not retained in any of the regression models. This suggests that, when controlling for other potential factors, gender is not an important contributor. In our study, significantly more comorbidities, neuropathic pain, higher level of pain, pain-related disability, fatigue, anxiety and lower physical HRQOL were reported by females. Of note, deformities and functional limitations, such as restricted joint motion, were not assessed in this study and cannot be compared between genders. These differences in phenotypes could be a confounding factor worth investigating in future research.

Previous studies in chronic musculoskeletal disease have established an association between activity limitations and a lower HRQOL11,18. In our study, greater pain-related disability was linked to reduced physical HRQOL in patients with MO. Although we did not find a direct relationship between physical activity level (PAL) and HRQOL, previous literature suggests that PAL may indirectly influence HRQOL through its effects on pain, fatigue, and psychological distress49,50. These findings imply that interventions aimed at reducing pain-related disability could potentially improve physical HRQOL in this patient group. Further research is needed to confirm these pathways. Consistent with other chronic musculoskeletal pain populations, fatigue intensity, age, BMI, and pain characteristics, such as more pain locations and pain intensity were also negatively related to patients’ physical HRQOL10,50. In contrast to the study of D’Ambrosi et al. (2017), more surgical interventions (6–10 interventions) were negatively related to physical HRQOL. Conversely, the lower HRQOL observed may indicate a more severe phenotype that might require additional surgical interventions, potentially explaining this outcome.

Higher anxiety scores were positively related to physical HRQOL, although only explaining 1.8%, while the opposite direction was expected15. The SF-36 PCS score increases with 0.447 for every point higher on the anxiety subscale, but the reason for this inversed directionality is unclear. Surprisingly, depressed mood and pain catastrophizing did not remain in the model15,18, but fear-avoidance beliefs were negatively associated with physical HRQOL18. On average, it seems that psychological factors, which are often reported and negatively associated with physical HRQOL in other chronic pain populations13,18, are less present in (or recognized by) patients with MO. Our sample is merely a cross-section of the total population and included patients who do not necessarily have high care needs. It is plausible that differences exist in the presence of psychological factors and their impact on HRQOL between patients with different care needs. Borsbö et al.15 identified four subgroups based on depression, anxiety, catastrophizing, pain intensity and duration in chronic pain patients (spinal cord injury, whiplash and fibromyalgia). Two subgroups who scored high on psychological factors reported lower HRQOL and more disability than the two subgroups who scored (relatively) low on psychological variables15. Subgrouping of patients based on psychological variables could have added value when investigating HRQOL.

The educational level was also positively related to physical HRQOL, in accordance with previous results of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain10,49,50. Salaffi et al.10 hypothesized that a higher education may lead to more self-efficacy and consequently to a better self-management of disease-related symptoms and disability.

Hypothesis (5): female gender, being single, a lower educational level, malignancy, more surgical interventions, higher intensity level of pain and fatigue, and presence of psychological factors are negatively associated with mental HRQOL.

In the final mode female gender, being single, malignancy and amount of surgery were not retained. Conversely, higher levels of anxiety and depressed mood were related to lower mental HRQOL, similar to healthy subjects15,51. While pain intensity did not remain in the final model, fatigue intensity was negatively associated with mental HRQOL. This result shows that in MO like other musculoskeletal disorders, fatigue has a stronger impact than pain on mental HRQOL16,52. The negative association of a higher educational level with mental HRQOL is unexpected, as it seems to be positively related to self-efficacy10,50 and adequate coping skills which mediate the relationship between sense of coherence and mental HRQOL53. An underrepresentation of patients with a primary educational level (n = 2) and, surprisingly, slightly higher mental HRQOL experienced by these patients than those with a higher educational level in our sample seems to underlie this result.

In our sample, more pain-related disability was slightly positively related to mental HRQOL, while other studies in chronic pain patients found more perceived disability to be related to lower overall HRQOL15,54. A possible explanation could be that patients with MO have adapted to their situation55, keeping in mind that nearly all patients are diagnosed at a young age, and by the age of 12 years7 at the latest. Patients’ adaptation to their chronic illness and disability, and its relationship with HRQOL should be explored further. On average, the PDI score is relatively low. This may be partly explained by our recruitment from both an expertise center as through the patient association. It is possible that our patient sample had a lower intensity of care compared to patients who are hospitalized or had recent surgery.

Limitations

First, reference scores from the general Dutch population used to compare patients’ PAL and HRQOL scores date from 198228 and 199829, respectively, and may be less representative of the current population.

Second, as this is a cross-sectional study, conclusions on causality cannot be drawn but require a longitudinal study.

Due to the recruitment procedure (expertise center and patient association) there is a possible under- or overrepresentation of persons who are asymptomatic or experience only mild symptoms. However, the number of completed questionnaires was high and patient characteristics showed a large degree of variability between patients, suggesting that both patients with no or mild and patients with severe symptoms were represented in our sample. Nevertheless, a potential selection bias cannot be excluded.

Even though the range of scores on psychosocial and symptom-related variables was large, we did not analyze our data based on known subgroups identified in other chronic disorders15. Due to the knowledge gap on aforementioned associations in patients with MO, a first exploration of the PAL and HRQOL, and associated patient-specific factors, symptom severity and psychological factors was necessary. A subsequent exploration of subgroups in the MO population could further clarify the association between psychological and symptom-related variables and the dependent variables (PAL and HRQOL). These additional insights could provide supplementary information for health professionals and support the development of individualized treatment programs.

Due to our study design, we relied on self-reported measures, which are susceptible to known biases such as recall bias. Subjective estimates of PAL may also differ from objectively measured data. For this study, we preferred a large sample size over the ‘objectivity’ of outcome measures. To minimize participant burden and maximize recruitment, we chose self-reported methods rather than multiple in-person assessments or additional objective measures.

Regarding our sample size, we did not perform a formal a priori power calculation (as noted in the Methods). Instead, we aimed for a convenience sample, as large as feasible within the study project’s constraints, to obtain the best possible estimates of our outcomes. We successfully enrolled a substantial cohort of individuals with MO—despite the rarity of this condition—which allowed us to develop robust regression models based on our theoretical framework. While additional associations may emerge with an even larger sample or an expanded set of variables, it is noteworthy that, to our knowledge, this is the largest adult MO population to date characterizing physical activity levels and health-related quality of life.

Clinical implications

Considering our results, the management of pain, depressive feelings and lifestyle to lower BMI, seem important components to enhance patients’ PAL. A higher PAL in turn can lead to less disease-related symptoms, psychological factors and lower BMI, creating a reciprocal relationship. Additionally, employment seems to contribute strongest to patients’ PAL and should be addressed in the treatment of working-age patients.

The relationship between the PAL and HRQOL seems rather indirect. We hypothesize that improvement of pain and fatigue, psychological factors and lifestyle leads to a higher PAL, less activity limitations and consequently higher mental and physical HRQOL.

Psychological variables such as depressive symptoms and catastrophizing were present in our sample and showed substantial variability, with depressive symptoms being negatively associated with both PAL and mental HRQOL It cannot be excluded that subgroups exist within the MO population, some of whom experience a larger psychological burden. Consequently, we recommend that psychological variables be routinely assessed and addressed during patient treatment.

Age and educational level were also related to mental and physical HRQOL. Even though these demographic factors are ‘non-modifiable’, they are important to consider during treatment. Focusing on self-efficacy, adequate coping skills and goal-oriented care could enhance patients’ ability to handle disease-related symptoms, help them to adapt to their chronic illness and thus improve their HRQOL.

Conclusions

This study provides important insights into the physical activity level and health-related quality of life of patients with MO, highlighting the significant impact of sociodemographic, illness-related, and psychological factors. Compared to healthy controls, patients with MO report lower physical HRQOL and PAL, which are associated with pain intensity, depressive symptoms and higher BMI. These results underscore the need for targeted interventions focusing on pain management, psychological factors, and lifestyle changes to improve both PAL and HRQOL in MO patients.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- BPAQ:

-

Baecke Physical Activity Questionnaire

- CIS:

-

Checklist individual strength

- DN4:

-

Douleur Neuropathique en 4 Questions (Neuropathic Pain Diagnostic Questionnaire)

- FABQ:

-

Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HME:

-

Hereditary multiple exostoses

- HRQOL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- ICF:

-

International classification of functioning

- MCID:

-

Minimal clinical important difference

- MD:

-

Mean difference

- MO:

-

Multiple osteochondromas

- MCS:

-

Mental component score (SF-36)

- NRS:

-

Numeric rating scale

- PAL:

-

Physical activity level

- PCS:

-

Pain catastrophizing scale

- PDI:

-

Pain disability index

- SF-36:

-

Short form-36

- SF-36 PCS:

-

Short form-36 physical component summary

References

D’Arienzo, A., Andreani, L., Sacchetti, F., Colangeli, S. & Capanna, R. Hereditary multiple exostoses: Current insights. Orthop. Res. Rev. 11, 199–211 (2019).

Schmale, G. A., Conrad, E. U. 3rd. & Raskind, W. H. The natural history of hereditary multiple exostoses. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 76(7), 986–992 (1994).

Goud, A. L., de Lange, J., Scholtes, V. A., Bulstra, S. K. & Ham, S. J. Pain, physical and social functioning, and quality of life in individuals with multiple hereditary exostoses in The Netherlands: A national cohort study. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 94(11), 1013–1020 (2012).

Porter, D. E. et al. Severity of disease and risk of malignant change in hereditary multiple exostoses. A genotype-phenotype study. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 86(7), 1041–1046 (2004).

Mordenti, M. et al. The Rizzoli multiple osteochondromas classification revised: Describing the phenotype to improve clinical practice. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 185(11), 3466–3475 (2021).

Darilek, S. et al. Hereditary multiple exostosis and pain. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 25(3), 369–376 (2005).

Wuyts, W., Schmale, G. A., Chansky, H. A. & Raskind, W. H Hereditary multiple osteochondromas. in GeneReviews((R)). Edn (eds Adam, M. P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G. M., Pagon, R. A., Wallace, S. E., Bean, L. J. H., Gripp, K. W. & Amemiya, A.) (Seattle, 1993).

Chhina, H., Davis, J. C. & Alvarez, C. M. Health-related quality of life in people with hereditary multiple exostoses. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 32(2), 210–214 (2012).

D’Ambrosi, R. et al. The impact of hereditary multiple exostoses on quality of life, satisfaction, global health status, and pain. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 137(2), 209–215 (2017).

Salaffi, F., Carotti, M., Gasparini, S., Intorcia, M. & Grassi, W. The health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis: A comparison with a selected sample of healthy people. Health Qual Life Outcomes 7, 25 (2009).

Anyfanti, P. et al. Predictors of impaired quality of life in patients with rheumatic diseases. Clin. Rheumatol. 35(7), 1705–1711 (2016).

Salaffi, F. et al. Health-related quality of life in fibromyalgia patients: a comparison with rheumatoid arthritis patients and the general population using the SF-36 health survey. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 27(5 Suppl 56), S67-74 (2009).

Lame, I. E., Peters, M. L., Vlaeyen, J. W., Kleef, M. & Patijn, J. Quality of life in chronic pain is more associated with beliefs about pain, than with pain intensity. Eur. J. Pain 9(1), 15–24 (2005).

Sprangers, M. A. et al. Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life?. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 53(9), 895–907 (2000).

Borsbo, B., Peolsson, M. & Gerdle, B. The complex interplay between pain intensity, depression, anxiety and catastrophising with respect to quality of life and disability. Disabil. Rehabil. 31(19), 1605–1613 (2009).

Gold, J. I., Mahrer, N. E., Yee, J. & Palermo, T. M. Pain, fatigue, and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic pain. Clin. J. Pain 25(5), 407–412 (2009).

Lazaridou, A. et al. The association between daily physical exercise and pain among women with fibromyalgia: the moderating role of pain catastrophizing. Pain Rep. 5(4), e832 (2020).

Shim, E. J. et al. Modeling quality of life in patients with rheumatic diseases: The role of pain catastrophizing, fear-avoidance beliefs, physical disability, and depression. Disabil. Rehabil. 40(13), 1509–1516 (2018).

Bathen, T., Fredwall, S., Steen, U. & Svendby, E. B. Fatigue and pain in children and adults with multiple osteochondromas in Norway, a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Orthop. Trauma Nurs. 34, 28–35 (2019).

Organization WH. Towards a Common Language for Functioning (Disability and Health. In., 2002).

Caspersen, C. J., Powell, K. E. & Christenson, G. M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 100(2), 126–131 (1985).

Lee, I. M. et al. Lancet physical activity series working G: Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 380(9838), 219–229 (2012).

Organization WH. Guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. In. (2020).

Anokye, N. K., Trueman, P., Green, C., Pavey, T. G. & Taylor, R. S. Physical activity and health related quality of life. BMC Public Health 12, 624 (2012).

Bize, R., Johnson, J. A. & Plotnikoff, R. C. Physical activity level and health-related quality of life in the general adult population: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 45(6), 401–415 (2007).

Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of web surveys: The checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 6(3), e34 (2004).

Castor Electronic Data Capture. https://castoredc.com.

Baecke, J. A., Burema, J. & Frijters, J. E. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 36(5), 936–942 (1982).

Aaronson, N. K. et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 51(11), 1055–1068 (1998).

Ware, Jr JE. ,. Snow, K., Kosinski, M. & Gandek, B. The SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. In. (2000).

McHorney, C. A., Ware, J. E. Jr., Lu, J. F. & Sherbourne, C. D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med. Care 32(1), 40–66 (1994).

Hawker, G. A., Mian, S., Kendzerska, T. & French, M. Measures of adult pain: Visual analog scale for pain (VAS Pain), numeric rating scale for pain (NRS Pain), McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ), short-form McGill pain questionnaire (SF-MPQ), chronic pain grade scale (CPGS), short form-36 bodily pain scale (SF-36 BPS), and measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 63(Suppl 11), S240-252 (2011).

Tait, R. C., Pollard, C. A., Margolis, R. B., Duckro, P. N. & Krause, S. J. The pain disability index: Psychometric and validity data. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 68(7), 438–441 (1987).

van Seventer, R. et al. Validation of the Dutch version of the DN4 diagnostic questionnaire for neuropathic pain. Pain Pract. 13(5), 390–398 (2013).

Elera-Fitzcarrald, C. et al. Measures of fatigue in patients with rheumatic diseases: A critical review. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 72(Suppl 10), 369–409 (2020).

Vercoulen, J. H. et al. Dimensional assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Psychosom. Res. 38(5), 383–392 (1994).

Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T. & Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 52(2), 69–77 (2002).

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 67(6), 361–370 (1983).

Sullivan, M. J. L., Bishop, S. R. & Pivik, J. The pain catastrophizing scale: Development and validation. Psychol. Assess. 7(4), 524–532 (1995).

Van Damme, S. et al. De pain catastrophizing scale: Psychometrische karakteristieken en normering. Gedragstherapie 33(0167–7454), 209–220 (2000).

Waddell, G., Newton, M., Henderson, I., Somerville, D. & Main, C. J. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain 52(2), 157–168 (1993).

Wat is HME/MO?. https://hme-mo.nl/over-hme-mo/wat-is-hme-mo/

O’Brien, R. M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factor. Qual. Quant. 41(5), 673–690 (2007).

Lubeck, D. P. Patient-reported outcomes and their role in the assessment of rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoeconomics 22(2 Suppl 1), 27–38 (2004).

Marques, A. et al. Cross-sectional and prospective relationship between physical activity and depression symptoms. Sci . Rep. 10(1), 16114 (2020).

McMahon, E. M. et al. Physical activity in European adolescents and associations with anxiety, depression and well-being. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 26(1), 111–122 (2017).

Teychenne, M., Costigan, S. A. & Parker, K. The association between sedentary behaviour and risk of anxiety: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 15, 513 (2015).

Fauske, L., Bruland, O. S., Grov, E. K. & Bondevik, H. Cured of primary bone cancer, but at what cost: A qualitative study of functional impairment and lost opportunities. Sarcoma 2015, 484196 (2015).

Lin, C. C. et al. Relationship between physical activity and disability in low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 152(3), 607–613 (2011).

Courbalay, A., Jobard, R., Descarreaux, M. & Bouvard, B. Direct and indirect relationships between physical activity, fitness level, kinesiophobia, and health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: A network analysis. J. Pain Res. 14, 3387–3399 (2021).

Garnaes, K. K. et al. What factors are associated with health-related quality of life among patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain? A cross-sectional study in primary health care. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 22(1), 102 (2021).

Eaton-Fitch, N., Johnston, S. C., Zalewski, P., Staines, D. & Marshall-Gradisnik, S. Health-related quality of life in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: An Australian cross-sectional study. Qual. Life Res. 29(6), 1521–1531 (2020).

Salaffi, F., De Angelis, R., Stancati, A., Grassi, W. & Pain, M. A. Prevalence IGs: Health-related quality of life in multiple musculoskeletal conditions: A cross-sectional population based epidemiological study. II. The MAPPING study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 23(6), 829–839 (2005).

Galvez-Sanchez, C. M., Montoro, C. I., Duschek, S. & Reyes Del Paso, G. A. Depression and trait-anxiety mediate the influence of clinical pain on health-related quality of life in fibromyalgia. J. Affect. Disord. 265, 486–495 (2020).

Kristofferzon, M. L., Engstrom, M. & Nilsson, A. Coping mediates the relationship between sense of coherence and mental quality of life in patients with chronic illness: A cross-sectional study. Qual. Life Res. 27(7), 1855–1863 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Dutch Patient Association ‘HME-MO Vereniging Nederland’ for their assistance with recruiting patients by sharing online information about the study on the patient association website. We thank all participants for taking time to complete the survey.

Funding

This research was supported by the Stichting Onderzoeksfonds HME-MO (The Netherlands, Haarlem) and Stichting Wetenschappelijk onderzoek OLVG (The Netherlands, Amsterdam).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IA was responsible for the study design, data acquisition, analyses and interpretation, as well as for drafting the manuscript, revision and final approval. KV was responsible for the analyses and interpretation, drafting the manuscript, revision and final approval. NW, JH, RS were involved in the study design, data interpretation, revision of the manuscript and final approval. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board of the OLVG (Reference No. WO 17.067). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. This study adhered to the ethical guidelines of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amajjar, I., Vergauwen, K., Willigenburg, N.W. et al. Physical activity level and health-related quality of life in adults with multiple osteochondromas: a Dutch cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 18990 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02812-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02812-3