Abstract

Prostate cancer frequently goes undetected at its early stage and it’s a major concern in the male population. To address this challenge, we provide a new approach based on electrochemical biosensing for the efficient detection of prostate cancer using PCA3 DNA biomarkers. Screen-printed paper electrodes were fabricated and modified with gold graphene quantum dots (Au-GQD), which were synthesized by an established domestic microwave method. Au-GQD, with their unique properties, find applications in various fields, including sensing, biomedicine, and catalysis, due to their enhanced catalytic activity, biocompatibility, and optical properties. Further, a PCA3 probe DNA was immobilized and characterized by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The developed sensing platform exhibits an excellent limit of detection (LoD) of 1.37 fM and 1.41 fM by CV and EIS, respectively. The limit of quantification (LoQ) is 4.08 and 4.27 by CV and EIS, respectively, within a linear range of detection (100 nM–100 fM). The stability of the developed sensor was found to be around 30 days with a hybridization time of 1 min. The proposed sensor effectively recognized PCA3 biomarkers in real urine amidst various interferents. In the future, the sensing platform could improve the prognosis of the disease by enabling early-stage identification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed non-skin cancer. Despite all medical facilities, it remains a big problem in the male population, and it is anticipated to impact 1.46 million individuals globally in 20221,2. By 2040, this number is expected to rise to 2.36 million, and 7.12 lacs deaths are also projected (WHO, CANCER TOMORROW)3. Prostate cancer is more prevalent in the age group of 55–65, and due to late diagnosis, prostate tumor converts into malignancies, which may lead to fatality4. It is a severe health risk, usually caused by the disruption in normal cell signaling. Many substances, including environmental factors, lifestyles, etc., indicate the alteration in genetic material, as the tumor usually grows slowly and indicates no initial symptoms. So, through early detection, we can change the scenario of prostate cancer2,5. The conventional techniques for the detection of cancers include PSA assay, MRI, CT-Scan, CTCs, etc. However, all conventional techniques lag with early detection and are expensive, time-consuming, and require a skilled workforce for their operation. In the upcoming era, biosensors can aid with these techniques to detect the disease early, with the advantage of mobility and cost-effectiveness6.

The prostate-specific antigen (PSA) concentrations found in blood samples are used as a biomarker to diagnose prostate cancer. Since 1991, PSA has been a globally accepted biomarker for Prostate cancer7. Significantly, elevated PSA levels may not always indicate malignancy because sometimes prostatitis may also lead to high levels of PSA; therefore, quantification of PSA and digital rectal examination (DRE) may lead to unnecessary biopsies or overdiagnosis. Consequently, PSA-based prostate cancer evaluation has been discouraged in the United States since 2008. But in 2017, it encountered an insignificant update8,9.

PCA3 is an alternative biomarker to differentiate between aggressive or non-aggressive tumors, initially recognized as Differential Display Clone 3 (or DD3) in 199910. It is a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) consisting of 3922 nucleotides. It is not believed to be associated with any other abnormalities of the prostate gland, thus becoming the potential biomarker for prostate cancer; following DRE, it was found in urine, peripheral blood, and prostate tumor samples, since urine is closely linked to the prostate gland, urine-based assessments are preferred. The ratio of urine PCA3 mRNA to PSA mRNA X 1000 was used to determine the minimal threshold value of the PCA3. According to the report analysis study “Physician brochure for progensa,” As the PCA3 Score rises, the possibility for a positive biopsy increases11,12. Since it is an entirely non-invasive approach, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved PCA3 as a urine biomarker for the diagnosis of prostate cancer in 2012. In the past, PCA3 has been frequently detected using Transcription-Mediated Amplification (TMA), fluorescence emissions, optical methods, and amplification from RT-PCR13. The current diagnostic process for detecting PCA3 through post-DRE in urine samples is approved for clinical use in the United States and has been released commercially. The Progensa test detects the occurrence of the PCA3 indicator using quantitative nucleic acid amplification with good sensitivity and specificity. Although these tests are usually costly, time-consuming, and require experts to perform their procedures. Therefore, there is an urgent requirement for more accessible, trustworthy, and affordable techniques for PCA3 identification14,15,16,17.

Advanced nanomaterials can play a significant role in fabricating an electrochemical biosensor. Electrochemical transduction technology has been widely employed in biosensing because of its simplicity, stability, fast reaction time, and miniaturization capabilities18,19. Nanoparticles or nanomaterials can enhance the biosensor’s performance, provide more accurate targeting, and increase the sensitivity of the developed sensor20,21,22,23,24. Incorporating 0D/1D/2D and 3D nanomaterials, such as Quantum dots, Carbon nanotubes, graphene oxide, MXenes, and gold nanoparticles, is frequently used to fabricate an electrochemical biosensor25. Carbon-based materials are among the most common in cancer detection due to their outstanding biocompatibility. At the same time, metallic nanoparticles, such as gold nanoparticles, are versatile and offer unique properties26,27. Along with these materials, screen-printed paper electrodes are frequently used for electrochemical biosensors28,29. The paper-based screen-printed electrode offers several advantages, including non-toxicity, cost-effectiveness, minimal sample requirement, and biodegradability, making it a sustainable and high-performance analytical tool and one of the primary advantages of cellulose is its porosity, which facilitates the capillary transport of solutions30,31,32. There is literature on electrochemical biosensors for the detection of PCA3, but mostly utilize quite expensive electrodes and materials, common materials which require lengthy set-up and the process’s complexity and cost, necessitating additional time and effort11,16,17,33.

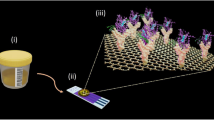

In this study, we propose a genosensor that can be built with a simple fabrication process based on Au-GQD nanohybrid modified screen printed paper electrode for early detection of prostate cancer, the use of paper electrode helps to reduce the cost per test, making it more affordable in resource-limited regions; it is also eco-friendly as it doesn’t cause micro-plastic contamination. Along with a novel PCA3 biomarker for prostate cancer identification. Electrochemical biosensors have exceptional sensitivity and enable the identification of analytes at the lowest concentrations. The PCA3 biomarker will not only reduce the overdiagnosis or false positives but also enhance sensitivity, along with accurate and early detection of prostate cancer. The PCA3 DNA sequences used in this study are as follows17.

Results

Microstructural characterization of bioelectrode

The UV–Vis spectra revealed two distinctive absorption peaks at 280 nm and 520 nm due to GQD and Au-GQD, as presented in Fig. 1A. These peaks indicate that Au-GQD is proficiently synthesized34. The band gap of Au-GQD is calculated to be 3.8 eV, implying excellent electrical properties of the material, shown in Fig. 1A(inset))35,36.

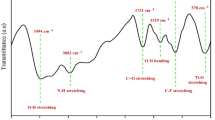

(A) UV–Vis. A spectrum of Au-GQD, inset: band gap of Au-GQD (B) FTIR spectrum of synthesized nanohybrid (C) XRD pattern of Au-GQD (D) DLS measurement of Au-GQD nanohybrid with PDI value of 0.18. (E) SEM image of the Au-GQD nanohybrid (scale bar 100 nm) (F) TEM image of Au-GQD hybrid with (scale bar 10 nm), inset; Particle size distribution and median particle size 9.69 nm.

FTIR spectrum of Au-GQD nanohybrid is shown in Fig. 1B. The prominent broad band was detected at 3443 cm−1, indicating O–H bond stretching. The expected carbonyl stretching frequency at 1700 cm−1–1725 cm−1 is shifted to 1634 cm−1 due to the binding of cationic gold. The typical peak of the C–O bond frequency is observed at 1036 cm−136. A small broad band around 2070 cm-1 may be due to nitrogen incorporation from the ambient air37.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of Au-GQD (Fig. 1C), showed characteristic diffraction peaks and variations. The diffraction peak at 21.63° is due to the presence of GQDs. However, the numerous diffraction peaks at 39.24°, 45.53°, and 62.75° represent the face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice of metallic gold (JCPDS no. 04-0784). The remaining peaks id due to substrate (ITO)34,38.

The particle size analysis of Au-GQD was performed using dynamic light scattering (DLS), and the graph represents a potential peak in the range 15–25 nm, indicating monodispersity as seen in Fig. 1D. At the nanoscale, the nanohybrid exhibits higher surface energy and larger surface area, which is crucial to enhancing biosensors’ sensitivity and specificity39. The obtained polydispersity index (PDI) is 0.18, which suggests that the synthesized nanohybrid’s size distribution is quite narrow, which may lead to more consistent and reliable responses40.

The Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the synthesized Au-GQD particles shows uniform distribution of the particles and their clusters (Fig. 1E). The average particle size of the round-shaped Au-GQD particles is observed to be in the range 5–30 nm. Some larger-sized particles can also be seen due to the accumulation and clustering of the smaller particles41,42.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), presented in Fig. 1F, reveals that particle are uniformly dispersed, and predominantly spherical, as observed in the high-resolution TEM image. The particle size distribution, shown in Fig. 1(F inset), indicates an average median particle size of 9.69 nm. The addition of tri-sodium citrate effectively stabilized the hybrid particles; however, some of the smaller particles exhibited aggregation, leading to the formation of larger, non-spherical structures34,43. This stabilization of Au-GQD particles due to addition of tri-sodium citrate can improve the sensing performance of Au-GQDs by enhancing their dispersion and maximizing their surface area, which is crucial for interaction with target molecules. The elemental mapping and EDX analysis of Au-GQD is presented in supplementary information (figure S1).

Electrochemical characterization of the Au-GQD/SPE

CV provides the information regarding oxidation–reduction processes, electrode kinetics, and controlled diffusion processes. To complement the cyclic voltammetry, EIS was employed, which provides significant information about the circuit and the behavior of its elements at the electrode–electrolyte interface. CV and EIS were performed for the electrochemical characterization of the developed sensor in the range of −0.6 to 0.6 V, scan rate 50 mV/s, and 0.1 Hz–0.1 MHz using PBS ferri-ferro cyanide (0.1 M, pH 7.0) electrolyte solution. The obtained voltammogram is presented in Fig. 2A. The current response of the Au-GQD/SPE was observed at 0.7 mA. Furthermore, the decrease in current response after the immobilization of the PCA3 capturing probe up to 0.66 mA, may be due to the charged backbone of a single-stranded DNA sequence made up of sugar and phosphates having a large number of negative charges exposed on the surface44.

The Au-GQD/SPE exhibits less resistance than the Au-GQD/SPE/probe, implying that after modification with the PCA3 capturing probe, the resistivity of the electrode interface increases, most likely caused by the electrical or steric effects of the nanohybrid, as depicted by the decreased current, complementing the voltammogram (Fig. 2B). The higher resistance obtained after immobilizing the probe with a large linker molecule (EDC/NHS) may hamper the electron transfer route and induce steric hindrance. The study utilizes Au-GQD nanohybrid due to the electrochemical and physical properties of GQD and Au. GQDs have shown promise in electrochemical sensors, which identify and measure target analytes by interpreting redox processes; moreover, GQDs exhibit excellent biocompatibility, stability, and large surface area for the biomarker. These attributes allow for low detection limits and increased sensitivity in GQD-based materials35,43,45. To produce a synergistic effect that speeds up the catalytic interaction with the target analyte, GQD is often mixed with other materials to form GQD-based nanocomposites or nanohybrids. The electronic energy transitions can be altered by the dopants, localized domains, lateral size, and functional groups on the GQD surface46. The functional groups on the GQD’s surface allow the material to link with other molecules or atoms, such as Au nanoparticles at one end, while other functional molecules, such as DNA, oligomers, etc., at the other end, to enable sensing capabilities. Au is a widely used metallic nanoparticle in biomolecule detection and cancer diagnosis47,48. A graphical representation of ionic interactions of Au-GQD with probe and target DNA molecules is presented in the supplementary information figure S2.

Discussion

The developed sensing platform is optimized at different parameters, including DNA probe concentration, hybridization time, and scan rate study, as presented in Fig. 3. The probe concentration for a wide range of DNA concentrations was employed from 10 to 40 µM, as shown in Fig. 3A. The Ipa significantly decreased (from 0.08 to 0.06 mA) upon increasing probe DNA concentration from 10 to 40 µM due to the charge repulsion caused by the negatively charged electrolyte and negatively charged phosphate backbone of the DNA49. Consequently, the optimum probe concentration is taken to be 20 µM for further experiments. The electrode stability test has been performed by CV, as seen in Fig. 3B. The voltammogram represents no significant change in the oxidation and reduction peak potential with a continuous rise in current response with an increased scan rate, indicating that a diffusion-controlled mechanism of the reversible system is likely occurring on the electrode–electrolyte interface. A linear plot of peak current versus the square root of the scan rate verifies the reversibility and diffusion-controlled properties of the redox probe as shown in Fig. 3C. At the same time, the study also verifies electrode stability. Additionally, the calibration curve for the scan rate study shows that the anodic and cathodic peak values exhibit corresponding R2 values of 0.98 and 0.97. The calculated electroactive surface area of the fabricated electrode is found to be 1.61 × 10–9 mm2 by employing the equation of Randles–Sevcik equation Ip = 2.69 × 105 A D1/2 n3/2 v1/2 C, where D is the diffusion coefficient, C is the concentration and n is the number of involved electrons50,51,52. To ensure minimum hybridization time, 2 µL of PCA3 Target DNA was employed on the surface of the Au-GQD/SPE/probe under optimized conditions (20 µM probe concentration), the hybridization duration was extended from 1 to 20 min, as presented in Fig. 3D. The current response dropped from 0.068 to 0.064 mA after the first 5 min and remained constant thereafter until 20 min. It demonstrates that the single-stranded DNA molecules were effectively hybridized to form a double-helix structure53.

The Au-GQD/SPE/Target’s analytical characteristics were investigated using CV and EIS in the potential range of −0.6 V to 0.6 V, scan rate 50 mV/s, and the frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 0.1 MHz, and the target concentration range of 100 nM to 100 fM as shown in Fig. 4. The voltammograms reveal that the addition of higher target concentration consistently results in a decrease in the anodic peak currents (Ipa) as shown in Fig. 4A, where the response at 100 nM TDNA shows nearly a two-fold decrease at 1 µM target concentration. At 100 fM, the Ipa was measured to be 0.069 mA, while at 100 nM, it decreased to 0.051 mA due to the pairing of the probe and target DNA, which produces a substantial double helix structure. The load of negatively charged moieties on the biosensor surface increased, which significantly inhibited the electron flow. Figure 4B shows the calibration plot for the target concentration between 100 nM and 100 fM, the graph shows linearity between Ipa and the target concentrations with R2 = 0.96. Moreover, the detection limit (LoD) was found to be 1.37 fM (LoD = 3 SD/m), and the limit of quantification (LoQ) was found to be 4.09 fM (LoQ = 10 SD/m), where m denotes the slope of the calibration plot, and SD stands for the standard deviation. The Nyquist plot, as shown in Fig. 4C, complements the voltammogram presented in Fig. 4A, where 100 fM exhibits less resistance while 100 nM shows high resistance. The EIS data also shows linearity among resistance and concentration and exhibits the R2 = 0.97 (Fig. 4D). The developed sensor shows LoD = 1.41 fM and LoQ of 4.27. Additionally, to strengthen experimental data and understand the composition of Randle’s circuit and their behavior, the simulation study was performed (a detailed description of the simulation is presented in supplementary information (figure S4 and Table S1)).

(A) Voltammogram showing the responses generated by Au-GQD/SPE/Target. (B) Calibration curve of Au-GQD/SPE/Target obtained from CV analysis. (C) Nyquist plot of Au-GQD/SPE/Target at different concentrations. (D) Calibration curve of Au-GQD/SPE/Target derived from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS).

The capability of the developed sensor to distinguish between PCA3 TDNA in a human urine sample (obtained from Mahavir Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Patna, Bihar, India) and the combination with non-complementary (NC) DNA (other target DNA in PBS) was studied by using 100 fM of PCA3 TDNA and NC DNA; the selectivity studies were carried out by employing cyclic voltammetry as shown in Fig. 5A, 2 μL of PCA3 TDNA and another molecule TDNA, respectively were immobilized on Au-GQD/probe modified electrode and the electrochemical characterization was performed. The PCA3 showed an Ipa value of 0.69 mA, and the developed sensor effectively recognizes PCA3 in human urine (spiked) sample and exhibits an Ipa value of 0.67 mA. HPV, along with CYFRA-21 and individual CYFRA-21, exhibits significantly less Ipa value comparatively.

The shelf life of the proposed sensor was monitored for up to 40 days under optimized conditions by employing cyclic voltammetry, as presented in Fig. 5B. The graph shows the Ipa value around 0.07 mA up to 28 days. A decrease in Ipa value was observed thereafter (0.062 mA), causing a decrease of 11.4%. This emphasizes the stability and consistency of the fabricated sensor’s up to around 30 days.

Conclusion

The present study establishes a method to fabricate a portable fabrication of DNA-based electrochemical biosensor for an early diagnosis of prostate cancer. An exclusive Au-GQD nanohybrid is used to smooth the capturing of the PCA3 DNA biomarker. The developed sensor showed LoD of 1.37 fM and LoQ of 4.08 fM for CV. Furthermore, the capturing of PCA3 is also monitored by the EIS technique and exhibits LoD of 1.41 fM and LoQ of 4.27 fM. The presented sensing platform established a wide linear range within Target DNA concentrations of 100 nM to 100 fM. The stability of the developed sensor was found to be around 30 days, with an excellent hybridization time of 1 min. The fabricated sensor presents improved sensing, hybridization time, and stability compared to other reported sensors in the literature, as presented in Table 1. The developed sensing platform and methodology are affordable and eligible for future commercialization as a diagnostic tool for cancer screening.

Method

Materials

Carbon conducting ink was purchased from BT-Corp Pvt. Ltd., India, a Microwave oven (make), Screen printer (Dashmesh Printer), and Electrochemical workstation (multiautolabM204, USA), were used for material synthesis, electrode fabrication, and electrochemical analysis, respectively. D-Glucose (Dextrose) was purchased from MERCK, Mumbai; Trisodium citrate, Sodium di-hydrogen orthophosphate (NaH2PO4), Di-sodium hydrogen Orthophosphate (Na2HPO4), and Potassium ferrocyanide were procured from Fisher Scientific, India. Chloroauric acid (HAuCl4.3H2O) was purchased from SRL, Mumbai, and Potassium ferricyanide and Sodium chloride were purchased from Central Drug House, New Delhi. Ethyl dimethylamine propyl carbodiimide (EDC). N- hydroxy succinimide (NHS), and DI water were procured from Sigma Aldrich, India. The amine-modified DNA sequences were purchased from Gene Bío Solutions, Dehradun, India.

PCA3 Probe sequences:

-

NH2-TTTTTTTCCCAGGGATCTCTGTGCTTCC

-

PCA3 Target sequences:—GGAAGCACAGAGATCCCTGGG

Synthesis of Au-GQD nanohybrids

Gold graphene quantum dot (Au-GQD) hybrid was prepared by chemical reduction of HAuCl4 facilitated by pre-formed GQD. The GQDs were synthesized by microwave-assisted hydrothermal treatment38 using a typical domestic microwave oven. So, the overall process is quick, scalable, and involves fewer chemicals. Chloroauric acid (HAuCl4.3H2O), tri-sodium citrate (stabilizing agent), and dextrose (carbon source) were used to synthesize the Au-GQD nanohybrid. The method of GQD synthesis was initiated by treating a 5 mL solution containing 0.6 M D glucose solution (5 mL) under microwave irradiation for 3–5 min at a constant power of 800 W. Afterwards, a 5 mL solution of 0.1 M trisodium citrate was carefully added for extraction of the resulting solution. The appearance of a pale-yellow color indicates GQD formation. For the synthesis of Au-GQD nanohybrid, 7 mM of 150 µL of HAuCl4.3H2O aqueous solution was added to the pre-formed GQD solution at room temperature, leading to the formation of Au-GQD hybrid particles via reduction of HAuCL4.3H2O to gold nanoparticles34. The synthesized nanohybrid was characterized using a UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV–VIS-1900), FTIR Spectroscopy (PerkinElmer Frontier), XRD (Malvern Panalytical Empyrean Series 3), SEM (FEI Quanta 450), TEM (ThermoFisher Talos F200X), and DLS (Malvern ZEN 1690 S).

Fabrication of sensing platform

The screen-printed paper electrodes (SPE) were developed in-house using carbon conducting ink and silver paste. The silver paste was used to fabricate a pseudo-reference electrode; a circular working electrode and counter electrode were printed using carbon conducting ink on paper through a commercial screen-printer. The printed paper electrode was modified with 5 µL of Au-GQD nanohybrid and kept for drying at room temperature. The nanohybrid-modified working electrode was further treated with 0.5 M EDC and 0.2 M NHS couple to activate the functional group present on the surface of GQD to bind to the probe DNA by forming NHS ester bonds. It leads to a monolayer of ssDNA-probe (Au-GQD/SPE/probe). The covalent bond is formed between the -NH2 group of the PCA3 probe and the -COOH functional group present on the GQD surface. The immobilization of probe DNA was confirmed by SEM and FTIR (supplementary information, figure S3).

A three-electrode system in Autolab consisted of Au-GQD/SPE/probe, carbon electrode, and Ag/AgCl, serving as the working, reference, and counter electrodes, respectively, to perform electrochemical measurements. A mixture of phosphate buffer saline and ferri-ferro cyanide (0.1 M and pH 7.0) was used as an electrolyte. Au-GQD/SPE/probe was analyzed by CV (−0.6 to 0.6 V at 50 mV/s) and (EIS) (0.1 Hz to 0.1 MHz). The scan rate study of the developed sensor was employed between a wide range from 10 to 80 mV/s. The developed sensor optimization was performed using CV in the range of −0.6 to 0.6 V. All experiments were performed three times (n = 3), and average data was plotted. A wide range of probe DNA (PDNA) concentrations (10–40 µM) were applied, along with a suitable hybridization period of 1–20 min to ensure a strong binding between the probe and target DNA (TDNA) molecules. The PCA3 target DNA was employed on the Au-GQD/SPE/probe within the concentration range of 100 nM to 100 fM with a volume of 2 µL. Furthermore, the storage or shelf-life investigation of the fabricated sensor was conducted for 40 days.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to further research and commercial prototype development but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, L. et al. Prostate cancer incidence and mortality: Global status and temporal trends in 89 countries from 2000 to 2019. Front Public Health 10 (2022).

Bergengren, O. et al. 2022 Update on prostate cancer epidemiology and risk factors: A systematic review. Eur Urol 84, 191–206 (2023).

Cancer Tomorrow https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en/dataviz/isotype?cancers=27&single_unit=50000&years=2040.

Rawla, P. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. World J Oncol 10, 63 (2019).

Prostate Cancer | Prostate Cancer Information and Overview | American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer.html.

Laraib, U., Sargazi, S., Rahdar, A., Khatami, M. & Pandey, S. Nanotechnology-based approaches for effective detection of tumor markers: A comprehensive state-of-the-art review. Int J Biol Macromol 195, 356–383 (2022).

Catalona, W. J. Prostate cancer screening. Med. Clin. North Am. 102, 199–214 (2018).

Dowlatshahi, S. & Abdekhodaie, M. J. Electrochemical prostate-specific antigen biosensors based on electroconductive nanomaterials and polymers. Clin. Chim. Acta 516, 111–135 (2021).

Review-recent advances in electrochemical detection of prostate specific Antigen (PSA) in clinically-relevant samples (2020) https://doi.org/10.1149/1945-7111/ab69fd.

Sánchez-Salcedo, R., Miranda-Castro, R., de-los-Santos-Álvarez, N. & Lobo-Castañón, M. J. Dual electrochemical genosensor for early diagnosis of prostate cancer through lncRNAs detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 192, 113520 (2021).

Takita, S., Nabok, A., Lishchuk, A., Mussa, M. H. & Smith, D. Detection of prostate cancer biomarker PCA3 with electrochemical apta-sensor. Eng. Proc. 16, 8 (2022).

Rodrigues, V. C. et al. Electrochemical and optical detection and machine learning applied to images of genosensors for diagnosis of prostate cancer with the biomarker PCA3. Talanta 222, 121444 (2021).

Merola, R. et al. PCA3 in prostate cancer and tumor aggressiveness detection on 407 high-risk patients: a National Cancer Institute experience. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer. Res. 34 (2015).

Wang, Y., Liu, X. J. & Yao, X. D. Function of PCA3 in prostate tissue and clinical research progress on developing a PCA3 score. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 26, 493 (2014).

Hessels, D. & Schalken, J. A. The use of PCA3 in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol 6, 255–261 (2009).

Nabok, A., Abu-Ali, H., Takita, S. & Smith, D. P. Electrochemical detection of prostate cancer biomarker PCA3 using specific RNA-based aptamer labelled with ferrocene. Chemosensors 9, 59 (2021).

Soares, J. C. et al. Detection of the prostate cancer biomarker PCA3 with electrochemical and impedance-based biosensors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 11, 46645–46650 (2019).

da Silva, E. T. S. G. et al. Electrochemical biosensors in point-of-care devices: Recent advances and future trends. ChemElectroChem 4, 778–794 (2017).

Baranwal, J., Barse, B., Gatto, G., Broncova, G. & Kumar, A. Electrochemical sensors and their applications: A review. Chemosensors 10, 363 (2022).

Zhu, C., Yang, G., Li, H., Du, D. & Lin, Y. Electrochemical sensors and biosensors based on nanomaterials and nanostructures. Anal Chem 87, 230–249 (2015).

Ramesh, M., Janani, R., Deepa, C. & Rajeshkumar, L. Nanotechnology-enabled biosensors: A review of fundamentals, design principles, materials, and applications. Biosensors (Basel) 13 (2023).

Malik, S. et al. Nanomaterials-based biosensor and their applications: A review. Heliyon 9, e19929 (2023).

Kong, X. et al. Facile synthesis of porous TiO2/SnO2 nanocomposite as lithium-ion battery anode with enhanced cycling stability via nanoconfinement effect. Chin. Chem. Lett. 35, 109428 (2024).

Liu, R. et al. Structure remodeling strategy for open-cage NiFe@Fe-bis-PBA with enhanced peroxidase-like activity to monitor tumor markers. Anal Chem https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.Analchem.4c02995/supplfile/ac4c02995_si_001.pdf (2024).

Pandey, R. R. & Chusuei, C. C. Carbon Nanotubes, graphene, and carbon dots as electrochemical biosensing composites. Molecules 26 (2021).

Mohammadnejad, J. et al. Electrochemical nanobiosensor based on reduced graphene oxide and gold nanoparticles for ultrasensitive detection of microRNA-128. Int Immunopharmacol 117, 109960 (2023).

Devi, K. S. S., Prakash, J. & Tsujimura, S. Graphene oxide-based nanomaterials for electrochemical bio/immune sensing and its advancements in health care applications: A review. Hybrid Adv. 5, 100123 (2024).

Mishra, A. et al. Progress in paper-based analytical devices for climate neutral biosensing. Biosens Bioelectron X 11, 100166 (2022).

Benjamin, S. R., de Lima, F., Nascimento, V. A. do, de Andrade, G. M. & Oriá, R. B. Advancement in paper-based electrochemical biosensing and emerging diagnostic methods. Biosensors (Basel) 13 (2023).

Taleat, Z., Khoshroo, A. & Mazloum-Ardakani, M. Screen-printed electrodes for biosensing: A review (2008–2013). Microchim. Acta 181, 865–891 (2014).

Benjamin, S. R., de Lima, F., Nascimento, V. A. do, de Andrade, G. M. & Oriá, R. B. Advancement in paper-based electrochemical biosensing and emerging diagnostic methods. Biosensors 13, 689 (2023).

Cao, J. et al. Hedgehog-like Bi2S3 nanostructures: A novel composite soft template route to the synthesis and sensitive electrochemical immunoassay of the liver cancer biomarker. Chem. Commun. 57, 1766–1769 (2021).

Mokni, M. et al. Designing a simple electrochemical genosensor for the detection of urinary PCA3, a prostate cancer biomarker. Micromachines 15, 602 (2024).

Wadhwa, S. et al. Engineering of luminescent graphene quantum dot-gold (GQD-Au) hybrid nanoparticles for functional applications. MethodsX 7, 100963 (2020).

Tian, P., Tang, L., Teng, K. S. & Lau, S. P. Graphene quantum dots from chemistry to applications. Mater Today Chem 10, 221–258 (2018).

Farouk Al-Hossainy, A., Abd-Elmageed, A. & ThA Ibrahim, A. Synthesis, structural and optical properties of gold nanoparticle-graphene-selenocysteine composite bismuth ultrathin film electrode and its application to Pb(II) and Cd(II) determination. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.06.020.

Ouyang, Z. et al. Preparation and specific capacitance properties of sulfur, nitrogen co-doped graphene quantum dots. Nanoscale Res Lett 14, 1–9 (2019).

Raj, D., Kumar, A., Kumar, D., Kant, K. & Mathur, A. Gold–graphene quantum dot hybrid nanoparticle for smart diagnostics of prostate cancer. Biosensors 14, 534 (2024).

Darwish, M. A., Abd-Elaziem, W., Elsheikh, A. & Zayed, A. A. Advancements in nanomaterials for nanosensors: A comprehensive review. Nanoscale Adv 6, 4015–4046 (2024).

Küçüktürkmen, B. et al. Microfluidic-assisted fabrication of dual-coated pH-sensitive mesoporous silica nanoparticles for protein delivery. Biosensors (Basel) 12, 181 (2022).

Wang, J., Liu, C. & Hua, J. Au–Ag nanoparticles-graphene quantum dots as sensor for highly sensitive electrochemical determination of insulin level in pharmaceutical samples. Int J Electrochem Sci 16, 211016 (2021).

Thakur, M. K. et al. Microplasma-enabled graphene quantum dot-wrapped gold nanoparticles with synergistic enhancement for broad band photodetection. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 12, 28550–28560 (2020).

Wadhwa, S., John, A. T., Nagabooshanam, S., Mathur, A. & Narang, J. Graphene quantum dot-gold hybrid nanoparticles integrated aptasensor for ultra-sensitive detection of vitamin D3 towards point-of-care application. Appl Surf Sci 521, 146427 (2020).

Singhal, C., Khanuja, M., Chaudhary, N., Pundir, C. S. & Narang, J. Detection of chikungunya virus DNA using two-dimensional MoS2 nanosheets based disposable biosensor. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–11 (2018).

Ozhukil-Valappil, M., Pillai, V. K. & Alwarappan, S. Spotlighting graphene quantum dots and beyond: Synthesis, properties and sensing applications. Appl. Mater. Today 9, 350–371 (2017).

Mobed, A., Kohansal, F., Dolati, S. & Hasanzadeh, M. A novel portable immuno-device for the recognition of lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor-1 biomarker using GQD–AgNPrs conductive ink stabilized on the surface of cellulose. RSC Adv 13, 30925–30936 (2023).

Chen, W. et al. Synthesis and applications of graphene quantum dots: A review. Nanotechnol Rev 7, 157–185 (2018).

Ibarra, D., Kharissova, O. & Gomez, I. Synthesis of graphene quantum dots coupled to Au nanoparticles: A facile and versatile route using different carbon sources. C 9, 45 (2023).

Maria Mourão Salazar Branquinho, R. et al. Label-free detection of biomolecules with Ta2O5-based field effect devices Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Nanotecnologias e Nanociências

Singh, D., Roy, S., Mahindroo, N. & Mathur, A. Design and development of an electroanalytical sensor based on molecularly imprinted polyaniline for the detection of thyroxine. J Appl Electrochem 54, 147–161 (2024).

Hondred, J. A., Medintz, I. L. & Claussen, J. C. Enhanced electrochemical biosensor and supercapacitor with 3D porous architectured graphene via salt impregnated inkjet maskless lithography. Nanoscale Horiz 4, 735–746 (2019).

Gharous, M. et al. Electrochemical kinetics and detection of paracetamol by stevensite-modified carbon paste electrode in biological fluids and pharmaceutical formulations. Int J Mol Sci 24, 11269 (2023).

Wei, N. et al. An electrochemical biosensor for detection of PML/RARA fusion gene using capture probe covalently immobilized onto poly-calcon carboxylic acid modified glassy carbon electrode. Talanta 78, 1227–1234 (2009).

Mokni, M. et al. Novel sensitive immunosensor for the selective detection of Engrailed 2 urinary prostate cancer biomarker. Biosens Bioelectron 217, 114678 (2022).

Farokhi, S., Roushani, M. & Saedi, Z. Fabrication of an electrochemical aptasensor for the determination of sarcosine based on synthesized CuCo2O4 nanosheets. Anal. Methods 15, 4938–4945 (2023).

Li, M., Zhang, W. & Zhang, Y. Aptamer–gold nanoparticle-signal probe bioconjugates amplify electrochemical signal for the detection of prostate specific antigen. Anal. Methods 13, 4150–4156 (2021).

Takita, S., Nabok, A., Lishchuk, A., Mussa, M. H. & Smith, D. Enhanced performance electrochemical biosensor for detection of prostate cancer biomarker PCA3 using specific aptamer. Eng 4, 367–379 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge SEED grant (UPES/R&D-SoAE/08042024/7), Indo-ASEAN R&D, CRD/2021/000472 grant, Suranaree University of Technology research grant (SRO 02/2568) for the financial support. We also acknowledge sensor fabrication lab (SFL) and the Central Instrumentation Centre (CIC), UPES for the support and infrastructure.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D. R.: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing original draft. S. W.: Methodology, Review and editing. S. R.: Simulation, Review and editing. A. K.: Review and editing. D. K.: Review and editing, Supervision. S. P.: Visualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition. K. K.: Visualization, Supervision, review and editing. A. M.: Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The project is approved by the research and ethical committee (Ref no. EC/NEW/INST/2022/2820), University of Petroleum and Energy Studies, Dehradun, for: All designed methods were carried out by following relevant guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols are approved by the University of Petroleum and Energy Studies, Dehradun, India, licensing committee. An informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raj, D., Wadhwa, S., Roy, S. et al. Affordable ultrasensitive electrochemical detection of PCA3 for early prostate cancer diagnosis. Sci Rep 15, 33849 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04852-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04852-1