Abstract

Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration (LCBDE) is highly effective for treating common bile duct stones (CBDS). This study aims to evaluate the safety and feasibility of primary closure with a self-disengaging biliary stent during LCBDE in patients with normal-diameter CBDs (≤ 8 mm) and to compare perioperative outcomes and complications with those in dilated CBDs (> 8 mm). From May 2022 to May 2024, patients with CBDSs who underwent LCBDE with primary closure and a self-disengaging biliary stent were retrospectively analyzed. Patients were stratified into two subgroups based on CBD diameter (normal: ≤8 mm vs. dilated: >8 mm). Propensity score matching (PSM) was adjusted for baseline differences between normal and dilated CBD groups, and perioperative indicators and postoperative complications were compared. Multivariate analysis identified risk factors for postoperative bile leakage. Of 491 patients, 343 underwent primary closure with a self-disengaging biliary stent during LCBDE. The mean operation time was 85 (IQR 70–110) min, with blood loss of 20 (IQR 15–20) ml. The postoperative hospital stay was 8 (IQR 8–10) days, and the hospitalization cost was CNY 28,143 (IQR 25,522–32,809). The overall complication rate was 32 (9.3%), with 25 (7.3%) experiencing bile leakage. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score was an independent risk factor for bile leakage (OR 2.587; 95% CI 1.729–3.873, P < 0.001). PSM of dilated (> 8 mm, n = 225) and normal (≤ 8 mm, n = 118) CBD groups resulted in 114 matched pairs. No significant differences were observed in operative time, blood loss, hospital stay, costs, or complications between the groups. Primary closure with a self-disengaging biliary stent following LCBDE is equally safe and effective in patients with normal-diameter CBDs as in those with dilated ducts. CBD diameter should not be a contraindication for this technique. The CCI score is a critical predictor of bile leakage and should be considered in perioperative risk assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As minimally invasive surgery has advanced, the approach to managing common bile duct stones (CBDSs) and gallbladder stones has evolved. Initially, open common bile duct exploration was used, but now Endoscopic retrograde Cholangiography (ERCP) with interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the preferred approach. In Western countries, the two-stage ERCP + LC method remains the initial treatment option1. However, over the past two decades, the rapid progress in laparoscopic techniques and equipment, alongside the increased emphasis by surgeons on preserving the function of the Sphincter of Oddi, has led to the widespread adoption of Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration (LCBDE). This has accumulated significant clinical experience, establishing LCBDE as the preferred surgical method for CBDSs in China and many other Asian countries2,3,4. Compared to ERCP, LCBDE shows shorter lengths of stay and lower costs. Additionally, there was no difference in morbidity, mortality, or rate of retained stones comparing LC plus LCBDE vs. preoperative ERCP and LC5,6. Moreover, increasing clinical data has demonstrated the efficacy and safety of primary closure7. Specifically, using biliary drainage through the intraoperative placement of biliary stents by choledochoscopy has effectively reduced the postoperative bile leakage rate8,9.

Based on our extensive experience with over 1,200 cases of LCBDE, we have adopted self-disengaging biliary stents (manufactured in-house) combined with primary closure after successful removal of CBDSs. This approach has led to favorable clinical outcomes. However, the safety and efficacy of LCBDE in patients with non-dilated common bile ducts remain a subject of clinical controversy8,10,11,12. In this retrospective study, we analyzed clinical data from patients with choledocholithiasis who underwent LCBDE with primary closure and self-disengaging biliary stent drainage at our hospital. We aimed to evaluate the risk factors for postoperative bile leakage in patients undergoing primary closure with a self-disengaging biliary stent following LCBDE. Additionally, we compared perioperative outcomes and complication rates between patients with normal-diameter (≤ 8 mm) and dilated common bile ducts to determine the safety and feasibility of this procedure in managing common bile duct stones in normal-diameter ducts.

Materials and methods

Patients diagnosed with choledocholithiasis at our hospital between May 1, 2022, and May 31, 2024, who underwent LCBDE with primary closure and self-disengaging biliary stent drainage were included. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Choledocholithiasis confirmed by imaging such as ultrasound scanning (USS), computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and without intrahepatic stones. (2) High suspicion of choledocholithiasis with a CBD diameter ≥ 5 mm and indications for CBD exploration; (3) Good organ function and tolerance for general anesthesia. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis (AOSC) requiring emergency biliary drainage. (2) Intraoperative challenges in completely removing CBDSs, necessitating placing a T-tube for drainage. (3) Abnormal duodenal papilla anatomy preventing stent placement. (4) Patients with acute biliary pancreatitis during the acute phase. (5) Biliary malignancies discovered during intraoperative exploration. (6) Patients with external biliary drainage such as Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangiographic Drainage (PTCD) or Retrograde Nasobiliary Drainage (RNBD). (7) Patients underwent transcystic exploration (TCE). Out of 491, 343 patients were included and divided into two groups based on the CBD diameter: the dilated group (> 8 mm, n = 225) and the normal group (≤ 8 mm, n = 118). The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of YiXing People’s Hospital (Ethical Review 2022 Medical-046). All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant ethical guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, in line with ethical standards (Fig. 1).

Study design with a flow diagram: Out of 491 consecutive patients diagnosed with CBDSs and treated between May 2022 and May 2024 at a single medical center, 343 were selected for the study. These patients were divided into two groups based on CBD diameter (8 mm): the normal group and the dilated group. Propensity score matching was conducted to match the two groups, aiming to reduce confounding factors such as age, gender, BMI, CCI score, ASA classification, history of abdominal surgery, preoperative hypoproteinemia, acute cholangitis, and obstructive jaundice.

Surgical technique

After successful induction of general anesthesia, the pneumoperitoneum is established below the umbilicus (Port A). For patients with a history of abdominal surgery, an open technique is used. Operating ports are positioned at the subxiphoid (Port B, 10 mm Trocar), 2 cm below the right costal margin (Port C, 5 mm Trocar), and 2 cm above the umbilicus on the right anterior axillary line (Port D, 5 mm Trocar). The gallbladder fundus and neck are retracted superiorly to the right to expose Calot’s triangle, which is meticulously dissected using monopolar surgical energy to expose the critical view of safety (CVS). The cystic duct and artery are ligated with clips. At the junction of the cystic duct and the CBD, the avascular plane on the anterior wall of the CBD is identified and dissected. The anterior wall of the CBD is incised longitudinally using a diathermy hook for 5 mm. A choledochoscope is introduced through Port B to inspect the CBD interior. Holmium laser lithotripsy may be used for large or impacted stones. All stones are retrieved using a basket. The intrahepatic ducts and distal CBD are inspected to ensure no residual stones remain, with a 360°rotational withdrawal of the scope to confirm complete clearance.

Papillary function is assessed by: (1) injecting pressurized saline under direct visualization with the choledochoscope to observe the contraction of the Sphincter of Oddi and evaluate its function; (2) passing a stone retrieval basket through the papilla into the duodenum in a closed state and then withdrawing it back into the bile duct in an open state to confirm papillary patency. A self-disengaging biliary stent, made from a 6 Fr ureteral double-J stent, is placed by advancing it over a guidewire that has been introduced through the choledochoscope into the CBD and then passed through the duodenal papilla, ensuring correct placement under direct visualization (Fig. 2).

The self-disengaging biliary stent-making and fixing procedure. a–c A 6-Fr double J tube was trimmed to approximately 15 cm in length. A terminal coil was fashioned at one end using 4-0 coated Vicryl® (polyglactin 910) sutures; d Following stone removal, a guidewire was first positioned through the working channel of the choledochoscope under direct endoscopic visualization. The choledochoscope was then carefully withdrawn while maintaining stable guidewire access. Finally, the self-disengaging stent was advanced over the guidewire into position; e Confirm the stent is positioned under choledochoscopy, passing through the papilla into the duodenum; f Perform the primary closure of the CBD and temporarily fix the stent by looping the coil at the end of the stent into the suture line.

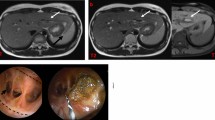

The CBD incision is closed with 4 − 0 absorbable PDS sutures, with a 1 mm margin and 2–3 mm stitch intervals, ensuring tight suturing to prevent bile leakage. The gallbladder is then routinely removed. Drainage is placed in the foramen of Winslow and below the right lobe of the liver, and they pass through Ports C and D to exit the body (Fig. 3).

General procedure for dilated CBD. a Explore Calot’s triangle and make a longitudinal incision on the anterior wall of the CBD; b Bluntly dilate the incision on the bile duct; c Explore the CBD with a choledochoscope and remove all stones; d Place the stent under the guidance of the choledochoscope; e Use 4-0 PDS sutures for interrupted suturing and temporarily fix the stent; f After complete suturing, check the CBD for the absence of stenosis and bile leakage.

For the normal CBD, a “micro-incision” technique is employed. The cystic duct is incised longitudinally towards the CBD for approximately 2 mm and gently dilated using operating forceps. An ultra-thin choledochoscope is used for stone removal and bile duct stent placement, following the same steps as the conventional choledochoscope procedure. The micro-incision in the CBD is sutured with 4 − 0 absorbable PDS sutures (margin of 1 mm, stitch interval of 2–3 mm), ensuring complete reconstruction of the cystic duct junction. Subsequent gallbladder removal and drainage placement are performed as previously described (Fig. 4).

CBD micro-incision process. a Dissect the Calot’s triangle and clamp the cystic duct; b make a longitudinal incision at the junction of the cystic and CBD, and make a small incision on the side wall of the CBD; c bluntly dilate the incision on the bile duct; d explore the CBD with a choledochoscope and remove all stones; e perform interrupted suturing of the small incision on the CBD, reconstruct the cystic duct, and temporarily fix the stent tube. f After complete suturing, check the CBD for the absence of stenosis and bile leakage.

Follow-up

All patients were followed up in the outpatient department, with each undergoing at least one liver function test and hepatobiliary USS. CT or MRCP was performed when residual or recurrent stones were suspected. Further treatment was guided by the review results. ERCP was performed for residual or recurrent CBDSs, with reoperation considered if ERCP failed. Biliary stent implantation was the first choice for postoperative biliary stricture. Patients with normal liver function and imaging and no discomfort had no further inspections. The follow-up duration ranged from 1 to 22 months (median, nine months).

Observation index and standard

Demographic characteristics and patients’ preoperative, operative, postoperative, and follow-up data were reviewed. The details were as follows: age, gender, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification System (ASA), obstructive jaundice, acute cholangitis, history of abdominal surgery, diameter of CBD, preoperative hypoproteinemia, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) respectively. Intraoperative parameters: open conversion, operation times, intraoperative blood loss. Postoperative parameters: postoperative hospital stay, hospitalization costs, and complications. Follow-up parameters: residual or recurrence CBD stones, bile stricture. The postoperative complications were judged according to the Clavien-Dindo classification system for surgical complications13. The definition and classification of bile leakage are provided by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery14.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM et al.). Measurement data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (for normally distributed data) or median (for non-normally distributed data). Normally distributed data were compared using the Student’s t-test, while non-normally distributed data were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Count data were expressed as rates and compared using the Pearson Chi-Square or Fisher’s exact test. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to analyze the risk factors for bile leakage. Propensity score matching (PSM ) was used to minimize differences in clinical characteristics between the dilated and normal groups. A logistic regression model was used to calculate the propensity score of the case based on age, gender, BMI, CCI score, ASA classification, history of abdominal surgery, preoperative hypoproteinemia, acute cholangitis, and obstructive jaundice. The nearest neighbor matching with a 1:1 ratio and a caliper value of 0.02 was utilized. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographics and perioperative outcomes

During the study period, 343 out of 491 patients underwent LCBDE + PC + self-disengaging biliary stent drainage. The baseline characteristics and outcomes following the procedure are summarized in Table 1. There were no conversions to open surgery and only one postoperative death within 30 days, involving a patient over 90 years old with multiple underlying conditions who succumbed to irreversible septic shock. One patient required transfer to the ICU for transitional treatment postoperatively due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The average age of the patients was 62.6 ± 14.8 years, and 48.1% were female. The mean CBD diameter was 10 (IQR 8–12) mm. Among the 343 patients, 118 (34.4%) had CBD diameters within the 5–8 mm range, including 3 patients (0.9%) with 5 mm, 22 (6.4%) with 6 mm, 36 (10.5%) with 7 mm, and 57 (16.6%) with 8 mm. The remaining 225 patients (65.6%) exhibited CBD diameters > 8 mm. The mean CCI score was 2 (IQR 1–4). A history of abdominal surgery was reported in 15.5% of patients. The incidence of acute cholangitis, obstructive jaundice, and preoperative hypoproteinemia was 20.7%, 44%, and 23.6%, respectively. ASA classifications were as follows: 4.1% (I), 65.6% (II), 30% (III), and 0.3% (IV). The mean operation time was 85 (IQR 70–110) min, with blood loss of 20 (IQR 15–20) ml. The postoperative hospital stay was 8 (IQR 8–10) days, and The hospitalization cost was 28,143 (IQR 25,522 − 32,809) CNY. The overall complication rate was 9.3% (32/343). The mortality rate was 0.3% (1/343). Bile duct-related complications occurred in 7.9% (27/343) of patients, with bile leakage observed in 7.3% (25/343), bile duct stricture in 0.3% (1/343), and recurrence of bile duct stones in 0.6% (2/343). Pulmonary infection was noted in 2% (7/343) cases (Tables 1 and 2).

Comparison of patients with or without bile leakage

Table 1 summarizes the comparisons of patients with or without bile leakage. The bile leakage group had significantly higher CCI scores and a higher incidence of acute cholangitis (P < 0.001 and P = 0.050, respectively). However, the two groups had no significant differences regarding age, gender, ASA classification, history of abdominal surgery, CBD diameter, preoperative hypoproteinemia, obstructive jaundice, operative time, and operative blood loss (all P > 0.05). Bile leakage leads to a higher incidence of associated complications, prolonged hospital stays, and increased hospitalization costs (P = 0.005, P = 0.001, P = 0.006, respectively).

Risk factors for bile leakage in patients who underwent LCBDE + PC + self-disengaging stent biliary drainage

We conducted multivariable logistic regression analyses to identify risk factors for bile leakage. Based on clinical experience and univariate analysis results, we included age, acute cholangitis, and CCI scores in the further analysis. The results indicated that a higher CCI score was a significant risk factor for bile leakage (OR 2.587; 95% CI 1.729–3.873, P < 0.001), whereas age appeared to be protective against bile leakage (OR 0.917; 95% CI 0.872–0.963, P = 0.001, Table 3).

Intraoperative, postoperative, and follow-up data: comparison between dilated CBD (dilated group) and normal CBD (normal group)

After PSM, 114 matched patient pairs were obtained with no significant differences in baseline characteristics (Table 4). Comparison of surgical outcomes showed no significant differences between the groups in operative time, blood loss, postoperative hospital stay, or costs (all P > 0.05). Overall complication rates were similar (10.5% vs. 11.4%, P = 1.000). Subgroup analysis also revealed no significant differences in bile leakage (10.5% vs. 7.0%, P = 0.349), biliary stricture (0 vs. 0.9%, P = 1.000), retained stones (0 vs. 0.9%, P = 1.000), pneumonia (1.8% vs. 2.6%, P = 1.000), or 30-day mortality (0 vs. 0.9%, P = 1.000) (Table 5).

Discussion

Multiple studies, including those by the European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES), and the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG), have shown that both single-stage and two-stage approaches are viable treatment options for patients with CBDS15,16,17,18. However, in Western countries, the two-stage approach is overwhelmingly preferred, with LCBDE used in less than 5% of cases in the US as of 201619. During an academic visit to a European teaching hospital, it was observed that surgical wards rarely handle CBDS cases, limiting surgeons’ experience with LCBDE—a trend also noted in the UK, Spain, and the US1,20,21. This is largely due to the widespread adoption of ERCP-first strategies, leaving surgeons with limited exposure to diagnostic and therapeutic techniques in LCBDE, including suturing and cholangioscopy22. Consequently, many perceive LCBDE as technically challenging, leading to reluctance in its use; a UK survey found that one-third of doctors subjectively reject this approach for the same reason1.

Despite these challenges, there is growing advocacy in the West for revisiting CBDS management strategies and enhancing LCBDE training, with experts predicting its resurgence as a routine treatment within five years21,22,23. In contrast, Chinese surgeons have accumulated extensive experience in LCBDE over the past two decades, leading to expanded indications and reduced complication rates. As a result, LCBDE is gradually gaining preference as a method for CBDS treatment, with the potential to replace the two-step approach24. This contrast highlights the importance of reviewing and sharing China’s clinical experiences to inform international practice and collaboration.

In this study, we analyzed 343 patients who underwent LCBDE with primary closure at a single medical center, performed by four standardized medical teams with consistent operation processes and postoperative management strategies. The operation time, postoperative hospital stay, and hospitalization cost were all significantly better than those observed with the pre-ERCP plus LC approach during the same period at our hospital (all P < 0.001; Supplementary Table 1). These economic indicators are consistent with those reported in other studies25,26.

In Western countries, LCBDE is commonly performed via the cystic duct, which has been associated with shorter hospital stays and lower complication rates26,27. A meta-analysis of 18 trials involving 2782 patients found no significant difference in stone clearance between LCBDE (n = 1222) and Laparoscopic Transcystic Common Bile Duct Exploration (LTCBDE, n = 1560)28. At our center, we explored the LTCBDE approach in patients with a larger cystic duct, managing approximately 85 cases since the introduction of LCBDE in 2012. Our experience showed that while this approach can be beneficial in selected cases, it also has notable limitations: Due to the sharp angle between the cystic duct and the common bile duct, maneuvering the choledochoscope is challenging, leading to significantly longer operation times. Most importantly, stone clearance efficiency is lower compared to direct choledochotomy. As our experience with LCBDE has grown, we have gradually shifted away from the LTCBDE approach in favor of direct access methods, which offer better stone clearance and shorter operation times. While our findings support the safety of choledochotomy in selected patients with CBD diameters of 5–8 mm, transcystic exploration remains the preferred first-line approach in most cases.

Our overall postoperative complication rate was 9.3%, including a 7.3% incidence of bile leakage, consistent with most literature reports7,11,29. Among the 25 cases of bile leakage, most were mild (Grade A), and no severe cases (Grade C) were observed. Although we used a self-disengaging biliary stent, it seems not effectively reduce the incidence of bile leakage. Several factors may explain this: First, our cohort had a relatively high proportion of elderly patients and those with elevated CCI scores, potentially contributing to the higher leakage rate. Second, we did not precisely assess the duration of adequate drainage provided by the stents. While over 90% of patients expelled the stents around 10–12 days postoperatively, we lack direct evidence to confirm their functionality during the critical 5–7 days when bile leakage is most likely to occur, underscoring the need for further research. Lastly, bile leakage incidence was initially 10% in the first 200 cases but decreased to 3.5% in the subsequent 143 cases with improvements in patient selection, suturing techniques, and perioperative management. This suggests that technical advancements and increased team experience are vital in reducing leakage rates, though further objective data are needed to support this conclusion.

We analyzed the risk factors for postoperative bile leakage by comparing the bile leakage and non-leakage groups. The bile leakage group had higher CCI scores and more cases of acute cholangitis (P < 0.001, P = 0.050). They also experienced more associated complications, longer hospital stays, and increased costs. Multivariable logistic regression identified CCI score as an independent risk factor (OR 2.587; 95% CI 1.729–3.873, P < 0.001). Age appeared protective, likely due to selection bias and proactive perioperative care in optimized elderly patients. These findings underscore the importance of perioperative management to mitigate bile leakage risks.

Previous studies have suggested that the diameter of CBD (> 8 mm) is a crucial indicator for evaluating whether primary closure can be performed following LCBDE. Liu et al.30 reported that the diameter of CBD and the surgeon’s experience were significant risk factors for bile leakage after primary closure following LCBDE. However, with a growing understanding of Oddi’s function, more evidence suggests that the feasibility of primary closure depends on complete stone removal, distal bile duct patency, and normal Sphincter of Oddi function8. A retrospective study by Yeon et al. primarily focused on the safety of LCBDE in patients aged ≥ 80 years. Notably, in their dataset, among the 337 cases that underwent primary closure with or without internal drainage, CBD diameter > 8 mm was not significantly associated with postoperative complications (P = 0.072)3. This suggests that CBD diameter may not be a decisive risk factor for complications after primary closure, indirectly supporting the safety of this approach in patients with CBD diameters < 8 mm. Similarly, Huang et al.31 demonstrated the feasibility of LCBDE in patients with smaller CBDs. Our clinical data align with these findings, showing no significant differences in perioperative safety or complications between the normal and dilated CBD groups.

In our cohort, primary closure was successfully performed in patients with CBD diameters between 5 and 8 mm, including 25 cases (7.3%) with ducts < 7 mm. Although encouraging, the small number of patients in this subgroup warrants cautious interpretation. Most patients classified as having “normal diameter” ducts fell within the 7–8 mm range, where our conclusions are more robust. These results support the safety and feasibility of primary closure with a self-disengaging biliary stent in selected patients with CBD diameters under 8 mm, while underscoring the need for further prospective studies to validate outcomes in very small ducts.

Ensuring complete ductal clearance is a fundamental condition for primary closure. Proficient use of the choledochoscope is crucial, and we follow standardized procedures to explore and evaluate the biliary tree, starting with the common bile duct, followed by the intrahepatic bile ducts, and then returning to the common bile duct. This is complemented by preoperative imaging assessments of stone size, location, and quantity. Typically, we explore the intrahepatic bile ducts up to the tertiary bile ducts and the distal bile duct up to the ampullary segment, slowly withdrawing the choledochoscope while rotating to avoid missing small stones. Many experts recommend routine intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) to ensure complete stone removal26. Due to equipment and transport limitations, our center uses Intraoperative Laparoscopic Ultrasound (IUS) when necessary to assess for residual stones in the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. However, based on our expertise with choledochoscopy and preoperative imaging, we achieve a high stone clearance rate. In this study, complete intraoperative stone clearance was achieved in all cases. However, two patients were found to have CBD stones on imaging at 3 and 11 months postoperatively. These stones differed notably in size and morphology from those identified preoperatively, suggesting recurrence rather than residual stones. Both were successfully treated with ERCP. That said, in the absence of immediate postoperative imaging, a definitive distinction between residual and recurrent stones cannot be established, which we acknowledge as a limitation of this study.

Assessing the functions of the Sphincter of Oddi is another critical process during LCBDE. In fact, its patency is the most important factor in deciding whether primary closure is feasible. In cases of Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction or associated ampullary anatomical anomalies, such as diverticula, primary closure should not be performed blindly. We usually employ an empirical judgment approach: if a stone retrieval basket in a closed state can pass through the Sphincter into the duodenum and then, in an open state, can be retracted back into the CBD, we consider the Oddi function to be fine.

Bile duct stricture is a crucial indicator for evaluating the long-term efficacy of primary closure32. The extra-hepatic bile duct, a fibromuscular structure, is repaired primarily through scar healing of the fibrous tissue. Excessive suturing of bile duct tissue is a significant cause of stricture. We routinely use 4-0 or 5-0 PDS for interrupted sutures, with a margin of 1 mm and a spacing of 2–3 mm. Although some literature reports no difference in postoperative complications incidence between interrupted and continuous sutures33continuous suturing in thinner bile ducts may cause tissue pulling and curling, increasing stricture risk. Secondly, preoperative imaging assessment is crucial15. By evaluating stone size and number, we can determine the appropriate extent of CBD incision, minimizing unnecessary damage to the CBD wall. Typically, we match the incision size to the stone, then gently expand it with dissecting forceps. Lastly, optimized case selection is essential for preventing complications. For dilated CBDs (over 10 mm), routine anterior wall incision and suturing are safe. For normal diameters (≤ 8 mm), we use a micro-incision approach at the cystic duct-CBD junction, utilizing the expansion at the junction to minimize bile duct wall damage (Fig. 4). Importantly, diathermy was deliberately avoided in these cases to reduce the risk of thermal injury. Instead, a 2–3 mm incision was made using scissors under direct vision. For CBD diameters less than 4 mm, we recommend cautious use of LCBDE, with ERCP being more appropriate in such cases.

In the present study, one postoperative bile duct stricture was observed, which was ultimately resolved through PTCD. After three months of supportive drainage, direct cholangiography revealed no bile duct stricture, allowing for the successful removal of the PTCD. Upon review of this case, it was noted that the patient presented with a CBD diameter of 7 mm and was complicated by acute cholecystitis. The routine longitudinal incision of the anterior bile duct wall performed by the surgeon may have contributed to this complication.

This study has several limitations. First, it is a single-institution, retrospective analysis, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Although efforts were made to mitigate bias, there remains a risk of unreliable conclusions. Additionally, 30% of patients were excluded due to alternative treatments (open surgery, ERCP, or T-tube placement), which may affect the external validity of the results. Larger, multi-center, prospective cohort studies are needed to compare the advantages of LCBDE with other traditional treatments. While surgical procedures and postoperative management were standardized across four medical teams, variations in surgeon experience could still introduce bias. The median follow-up period of nine months may have underestimated long-term complications, such as stone recurrence or bile duct stricture. Therefore, extended follow-up is essential for more accurate outcomes. Lastly, the absence of a comparison between clinical outcomes with or without stents in CBDs smaller than 8 mm limits the ability to assess the role of stents, and the small sample size restricts meaningful statistical analysis. Future studies should address these issues.

Conclusion

For CBDS patients with normal bile duct diameter, performing LCBDE with primary closure combined with a self-disengaging biliary stent does not increase perioperative risk or the incidence of short-term complications compared to patients with dilated bile ducts. The CCI score is an independent risk factor for bile leakage complication, indicating that primary closure should be carefully considered in patients with high CCI scores. After optimized case selection (e.g., low CCI score, CBD diameter ≥ 7 mm), this technique is safe and feasible when performed by an experienced surgeon.

Data availability

The data will be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Tanase, A., Dhanda, A., Cramp, M., Streeter, A. & Aroori, S. A UK survey on variation in the practice of management of choledocholithiasis and laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (ALiCE Survey). Surg. Endosc. 36, 5882–5896 (2022).

Chen, A. P. et al. Clinical dfficacy of primary closure in laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (a report of 2429 cases). Chin. J. Dig. Surg. 17, 299–303 (2018).

Yeon, H. J., Moon, J. I., Lee, S. J. & Choi, I. S. Is laparoscopic common bile duct exploration safe for the oldest old patients. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 26, 140–147 (2022).

Tan, Y. P., Lim, C., Junnarkar, S. P., Huey, C. & Shelat, V. G. 3D laparoscopic common bile duct exploration with primary repair by absorbable barbed suture is safe and feasible. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 7, 473–478 (2021).

Dasari, B. V. et al. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev CD003327 (2013).

Ricci, C. et al. Comparison of efficacy and safety of 4 combinations of laparoscopic and intraoperative techniques for management of gallstone disease with biliary duct calculi: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 153, e181167 (2018).

Lai, W. & Xu, N. Feasibility and safety of choledochotomy primary closure in laparoscopic common bile duct exploration without biliary drainage: a retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 13, 22473 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Efficacy and safety of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration with primary closure and intraoperative endoscopic nasobiliary drainage for choledocholithiasis combined with cholecystolithiasis. Surg. Endosc. 37, 1700–1709 (2023).

Xiao, L. K. et al. The reasonable drainage option after laparoscopic common bile duct exploration for the treatment of choledocholithiasis. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 42, 564–569 (2018).

Xiang, L. et al. Safety and feasibility of primary closure following laparoscopic common bile duct exploration for treatment of choledocholithiasis. World J. Surg. 47, 1023–1030 (2023).

Fan, L. et al. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration with primary closure could be safely performed among elderly patients with choledocholithiasis. BMC Geriatr. 23, 486 (2023).

Deng, M. et al. Greater than or equal to 8 mm is a safe diameter of common bile duct for primary duct closure: single-arm meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 15, 513–521 (2022).

Dindo, D., Demartines, N. & Clavien, P. A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 240, 205–213 (2004).

Koch, M. et al. Bile leakage after hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a definition and grading of severity by the international study group of liver surgery. Surgery 149, 680–688 (2011).

Williams, E. et al. Updated guideline on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut 66, 765–782 (2017).

ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. ASGE guideline on the role of endoscopy in the evaluation and management of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 89, 1075–1105e15 (2019).

Manes, G. et al. Endoscopic management of common bile duct stones: European society of Gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy 51, 472–491 (2019).

Fujita, N. et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for cholelithiasis 2021. J. Gastroenterol. 58, 801–833 (2023).

Wandling, M. W. et al. Nationwide assessment of trends in choledocholithiasis management in the united States from 1998 to 2013. JAMA Surg. 151, 1125–1130 (2016).

Jorba, R. et al. Contemporary management of concomitant gallstones and common bile duct stones: a survey of Spanish surgeons. Surg. Endosc. 35, 5024–5033 (2021).

Nyren, M. Q. et al. Surgical resident experience with common bile duct exploration and assessment of performance and autonomy with formative feedback. World J. Emerg. Surg. 18, 13 (2023).

Rendell, V. R. & Pauli, E. M. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. JAMA Surg. 158, 766–767 (2023).

VanDruff, V. N. et al. The laparoscopy in biliary exploration research and training initiative (LIBERTI) trial: simulator-based training for laparoscopic management of choledocholithiasis. Surg. Endosc. 38, 931–941 (2024).

Pan, L. et al. The safety and efficacy of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration combined with cholecystectomy for the management of Cholecysto-choledocholithiasis: an Up-to-date Meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. 268, 247–253 (2018).

Yan, Y. et al. One-stage versus two-stage management for acute cholecystitis associated with common bile duct stones: a retrospective cohort study. Surg. Endosc. 36, 920–929 (2022).

Nassar, A., Ng, H. J., Katbeh, T. & Cannings, E. Conventional surgical management of bile duct stones: a service model and outcomes of 1318 laparoscopic explorations. Ann. Surg. 276, e493–e501 (2022).

Hajibandeh, S. et al. Laparoscopic transcystic versus transductal common bile duct exploration: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. World J. Surg. 43, 1935–1948 (2019).

Feng, Q. et al. Laparoscopic transcystic common bile duct exploration: advantages over laparoscopic choledochotomy. PLoS One. 11, e0162885 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Efficacy and safety of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration via choledochotomy with primary closure for the management of acute cholangitis caused by common bile duct stones. Surg. Endosc. 36, 4869–4877 (2022).

Liu, D. et al. Risk factors for bile leakage after primary closure following laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Surg. 17, 1 (2017).

Huang, X. X. et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic bile duct exploration for choledocholithiasis with small common bile duct. World J. Clin. Cases. 9, 1803–1813 (2021).

Ahmed, E. A. & Redwan, A. A. Impact of choledochotomy techniques during laparoscopic CBD exploration on short- and long-term clinical outcomes: time to change concepts (a retrospective cohort study). Int. J. Surg. 83, 102–106 (2020).

Wu, D. et al. Primary suture of the common bile duct: continuous or interrupted. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A. 32, 390–394 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the assistance of Prof. Dr. Helmut Friess in guiding the revision of this manuscript.

Funding

Health Commission Scientific Research Fund Project of Wuxi city, China(Q202027); Municipal Health Commission General Fund Project of Yixing City, China(2022-14); Yixing People’s Hospital Institutional Research Project Funding (2024-A6).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yun Zhang, Feng Zhan and Chao Jiang designed the study ; Yu Zhang, Miao Zhang, Kai Zhang, Zhenghai Shen and Zhenwei Shen acquisited the data and prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4, and Table 1, and 2; Lixia Yang , Feng Zhan and Xiang Chen analysised and interpretaed the data and prepared Tables 3, 4 and 5; Feng Zhan, Chao Jiang and Lixia Yang drafted the manuscript; Yun Zhang, Xiang Chen and Feng Zhan perfromed critical revision of manuscript; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhan, F., Jiang, C., Yang, L. et al. Primary closure with self-disengaging biliary stent following laparoscopic CBD exploration in normal-diameter ducts: a propensity score matching study. Sci Rep 15, 19959 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04949-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04949-7