Abstract

Peptidylprolyl isomerase A (PPIA) is a key molecule involved in various biological functions and has been implicated in multiple diseases. However, the biological significance of PPIA in pan-cancer remains unclear. We assessed the pan-cancer expression, prognostic value, and biological functions of PPIA through multiple databases and multidimensional analysis. We also investigated the correlation of PPIA with the immune microenvironment, epigenetic modifications, and drug sensitivity. Expression validation was performed using Western Blot (WB) and quantitative PCR (qPCR). PPIA was found to be highly expressed in most cancers and identified as a prognostic risk factor. The expression of PPIA in most cancers showed significant correlations with immune cell infiltration, major histocompatibility complex, immune checkpoints, tumor mutation burden, microsatellite instability, RNA modifications (including m1A, m5C, m6A), and DNA methylation sites. It was widely enriched in pathways such as Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, Calcium signaling pathway, and cAMP signaling pathway in the pan-cancer context. PPIA plays a pro-tumor role in various cancers and could serve as a potential biomarker for predicting cancer prognosis and the efficacy of immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is a major global health challenge and one of the leading causes of death worldwide1. As a complex polygenic disease, the occurrence and development of cancer involve multiple genetic and environmental factors2. In recent years, with the rapid development of high-throughput sequencing technologies, cancer research has entered a new era. Traditional cancer research typically focuses on specific cancer types, whereas pan-cancer analysis offers a global perspective aimed at revealing the commonalities and differences between different cancer types3,4. This approach not only helps to understand the general biological characteristics of cancer but also promotes the development of cross-cancer treatment strategies.

In recent years, the role of immune-modulatory related proteins in cancer has gradually become a research focus, with cyclophilin A (CypA, encoded by the PPIA gene) attracting significant attention for its multifunctionality. PPIA is a ubiquitously expressed peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, initially identified as the intracellular receptor for the immunosuppressant cyclosporine A (CsA), involved in regulating T cell activation5. When PPIA binds to its cell surface receptor CD147, it may enable tumor cells to evade T cell immune surveillance6. The immunosuppressive activity of CsA is believed to originate from the binding of the CsA-PPIA complex to calcineurin7, and PPIA gene knockout mice are resistant to the immunosuppression by CsA8. However, besides its immunoregulatory role, PPIA also plays a critical part in cancer development by influencing cell cycle progression, resistance to apoptosis, and inflammatory responses through catalyzing protein folding, nuclear translocation, and regulating signal transduction. Studies have shown that knocking down PPIA expression can inhibit the tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) and induce interleukin-6 (IL-6)-dependent apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells9. PPIA enhances NF-κB transcriptional activity by directly binding to a specific sequence in the N-terminal of p65/RelA, promoting its nuclear translocation while maintaining protein stability10. Knocking down PPIA can inhibit the IL-8 activity induced by the NF-κB pathway, and hamper the proliferation and tumor growth of glioblastoma cells11. Additionally, PPIA can bind to the extracellular receptor CD147 and stimulate the expression of cyclin D1 and survivin through STAT3 phosphorylation, which co-localizes with the cancer stem cell marker CD44, promoting tumorigenesis and the growth of pancreatic cancer12. PPIA is upregulated in lung cancer, where it directly interacts with nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (NRF2) through a hydrophobic sequence containing trans-proline 174, preventing NRF2 ubiquitination and degradation, thus promoting the proliferation of lung cancer cells13. Moreover, PPIA has also been shown to be upregulated in esophageal cancer14 and breast cancer15. Although the mechanisms of PPIA in cancer regulation have been reported in some cancer types, a systematic analysis of its expression heterogeneity, epigenetic modification characteristics, and association with genomic instability at a pan-cancer level is still lacking.

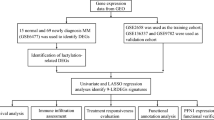

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive pan-cancer analysis of PPIA using pan-cancer data from multiple databases and cohorts, including TCGA, GTEx, and GEO. Our analysis covered various dimensions, including gene expression, single-cell expression distribution, epigenetic modifications, tumor immune characteristics, drug sensitivity, and prognosis analysis. Figure 1 summarizes the findings of this study.

Materials and methods

Data collection

We obtained the pan-cancer expression data and methylation data in TPM processed by the STAR pipeline from the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/)16. Clinical information, survival data, transcript expression data, and GTEx expression data for pan-cancer were retrieved from the UCSC Xena database (http://xena.ucsc.edu/)17. Single-cell transcriptome sequencing data for 13 types of cancer were obtained from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), with GEO accession numbers GSE161529 (triple-negative breast cancer)18, GSE138709 (intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma)19, GSE166555 (colorectal cancer)20, GSE196756 (esophageal squamous cell carcinoma)21, GSE139324 (HPV + HNSC)22, GSE121636 (KIRC)23, GSE149614 (hepatocellular carcinoma)24, GSE154109 (acute myeloid leukemia)25, GSE123902 (LUAD)26, GSE184880 (high-grade serous ovarian cancer)27, GSE137829 (castration-resistant prostate cancer)28, GSE167297 (diffuse-type gastric cancers)29, and GSE163203 (papillary thyroid carcinoma)30. To increase the reliability of our study, HCC data from the ICGC database (https://dcc.icgc.org/)31 was obtained as a validation set. Additionally, we validated the expression level of PPIA in HCC using multiple independent cohorts from the GEO database, with GEO accession numbers GSE1452032, GSE3637633, GSE4543634, GSE5423635, GSE6389836, GSE7642737, GSE11279038, and GSE12124839. Detailed cohort information is provided in Table S1. The study encompasses 33 cancer types, including Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), Bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA), Breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC), Cholangio carcinoma (CHOL), Colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), Lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBC), Esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), Kidney chromophobe (KICH), Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP), Acute myeloid leukemia (LAML), Brain lower grade glioma (LGG), Liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), Lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), Mesothelioma (MESO), Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV), Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PCPG), Prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD), Rectum adenocarcinoma (READ), Sarcoma (SARC), Skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM), Stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), Testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT), Thyroid carcinoma (THCA), Thymoma (THYM), Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC), Uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS), and Uveal melanoma (UVM).

Pan-cancer expression and prognosis analysis

The expression level of PPIA in pan-cancer and its corresponding normal tissues was explored using R software. The impact of PPIA on pan-cancer cell lines was analyzed through the DepMap platform (https://depmap.org/portal/)40. Within the “Dependent Cell Lines” module, the effect of PPIA knockdown on the viability of pan-cancer cell lines was assessed, where a gene score of 0 indicates no impact on cancer cell viability, and a negative score with a lower value suggests stronger inhibition of cancer cell viability, with the median score for common oncogenes being − 1. Survival data for 31 cancer types, including Overall Survival (OS), Disease-Specific Survival (DSS), Disease-Free Interval (DFI), and Progression-Free Interval (PFI), were obtained from UCSC Xena41. Subsequently, PPIA expression data were matched with survival data for each sample, and univariate Cox regression analysis and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis were performed using the “survival” and “forestplot” packages in R software to explore the correlation between PPIA expression levels and pan-cancer prognosis. Similarly, clinical information on 31 cancer types, including age, T, N, M stage, and overall stage status, was obtained from UCSC Xena. PPIA expression data were then matched with clinical information for each sample to analyze PPIA expression levels across different clinical groups. The “timeROC” package was used to plot Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves to evaluate the sensitivity and accuracy of PPIA for overall survival prognosis. Finally, the expression level of PPIA was also examined across different tumor stages.

Single-cell expression distribution in pan-cancer

To further explore the cellular expression distribution of PPIA in pan-cancer, we analyzed 14 scRNA datasets. The “Seurat (Version 5.2.1)” package was used to filter the datasets with specific criteria as follows: number of genes > 300, sequencing depth < 30,000, and mitochondrial ratio < 20%. NormalizeData, FindVariableFeatures, ScaleData, and RunPCA functions were applied for data normalization, identification of highly variable genes, and dimension reduction. Subsequently, the harmony method in the IntegrateLayers function was used to remove batch effects between samples and integrate the data, and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) was employed for further dimension reduction. FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions were utilized for cell clustering analysis. Finally, cell type annotation for each unit was performed based on marker gene expression, including T cells (CD3D, CD3E, TRAC, CD8A), NK cells (KLRD1, GNLY, NKG7), B cells (CD19, CD79A, MS4A1), macrophages (CD68, CD163, CD14), DC cells (CLEC9A, XCR1, CCL22, CD1E), mast cells (KIT, TPSAB1, TPSB2), fibroblast cells (COL1A1, FGF7, MME), endothelial cells (VWF, PECAM1, PLPP1), and malignant epithelial cells (EPCAM, KRT18, KRT19).

Tumor immune microenvironment and genetic alteration analysis

Three algorithms were used to assess the immune microenvironment score of pan-cancer samples: the ssGSEA algorithm provided by the R package “GSVA”42, which calculates immune infiltration based on markers of 24 types of immune cells43; the CIBERSORTx website (https://cibersortx.stanford.edu/) offers markers for 22 types of immune cells and uses the CIBERSORT algorithm script to calculate immune infiltration44; and the ESTIMATE algorithm provided by the R package “estimate” for calculating immune infiltration45. PPIA expression data for each sample were matched with immune infiltration scores, followed by correlation analysis. The ‘maftools’ package in R was used to evaluate the tumor mutation burden (TMB) score, while the microsatellite instability (MSI) score was obtained from previous reports46. Expression data for immune-related genes (including major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and immune checkpoints) and RNA modification-related genes (including m1A, m5C, and m6A) were extracted. Subsequently, the correlations between PPIA expression levels and TMB, MSI, and the aforementioned related genes were assessed.

Drug sensitivity analysis

Cancer samples were divided into high expression and low expression groups based on the median expression level of PPIA. Differential analysis was conducted to identify differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05, |LogFC|>1). Subsequently, the top 100 most significantly upregulated mRNA genes from each cancer type were uploaded to the SPIED3 platform (http://92.205.225.222/HGNC-SPIED3-QF.py). Using data from 1,309 compounds in the CMAP database as the reference dataset, compounds with negative correlation in the analysis indicated potential reversal of the expression trend of differential genes. Expression data for anti-PD-L1 therapy were obtained from the IMvigor210 dataset47, and the correlation between PPIA expression and immunotherapy response was analyzed. NCI-60 drug scoring data and RNA-seq expression data were downloaded from the CellMiner database (https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer/home.do)48, and drugs approved by the FDA and clinically verified were filtered out to explore their correlation with PPIA.

Pan-cancer enrichment analysis

Cancer-related signature gene set files were downloaded from the Molecular Signatures Database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb)49. Based on the differential analysis results between the high and low PPIA expression groups, a GSEA enrichment analysis was conducted using the “clusterProfiler” package. In this study, the KEGG gene set and Hallmark gene set were selected as references, and the normalized enrichment score (NES) and false discovery rate (FDR) were calculated.

Expression validation in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines

The cell lines HepG2, HUH-7, and THLE2 were acquired from ProCell (Wuhan, China), while MHCC-97 H was sourced from Fenghui Biological (Hunan, China). The human HCC cell lines, including HepG2, HUH-7, and MHCC-97 H, were cultured using high-glucose DMEM (Gibco, USA). In contrast, THLE2, representing normal liver cells, were grown in BEGM (Thermo fisher scientific, USA). Both types of culture media were enhanced with 10% fetal bovine serum and kept in a 5% CO2 incubator (Heal force, China) at a stable temperature of 37 °C.

Proteins were extracted from cells using RIPA buffer (Solarbio, China), and their concentrations were determined with a BCA kit (Solarbio, China). The expression of PPIA (1:1000, A0993, ABclonal, China) across these cell lines was analyzed through western blotting (WB).

To assess the mRNA expression of PPIA in the above cells, RT-qPCR was conducted. Total RNA was extracted using the Promega kit and quantified. cDNA was synthesized with a reverse transcription kit. The PCR protocol included 40 cycles with the following conditions: pre-denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 30 seconds. GAPDH served as an internal control, and the relative expression level of PPIA was calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method. Primer sequences (Bioengineering Co., Ltd, Shanghai): PPIA, forward 5’-TACAGTGCTTGCTGGCAGTT-3’ and reverse 5’-TCCGCCACCTCTAGGATAGG-3’; GAPDH, forward 5’-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3’ and reverse 5’- GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3’.

Statistical analysis

Correlation analyses between two variables were performed using the Spearman method. Differences between two groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. For comparisons among more than two groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test was employed. Kaplan-Meier (K-M) curves and the Cox proportional hazards regression model were used for survival analysis. Statistical analyses and graphical plotting were conducted using R software (version 4.3.2). A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A p-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Abnormal expression of PPIA in pan-cancer

We used expression data from TCGA and GTEx to comprehensively analyze the differential expression of PPIA in various tumor tissues and normal tissues. Overall, PPIA is dysregulated in most tumors, primarily with upregulated expression, including BLCA, BRCA, CESC, CHOL, COAD, ESCA, GBM, HNSC, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LIHC, LUAD, LUSC, PRAD, READ, STAD, THCA, and UCEC, while it is downregulated in LAML (Fig. 2A-B). Given the widespread dysregulation of PPIA in pan-cancer, we further analyzed the expression differences of different PPIA transcripts in normal and tumor tissues. The results show that protein-coding transcripts are upregulated in various cancers, while transcript expression is downregulated in LAML (Fig. 2C). Notably, a nonsense-mediated decay (NMD)-related transcript of the PPIA gene (ENST00000415933) is upregulated in a variety of tumor tissues, which may be associated with NMD escape, gene mutations, and abnormal splicing50. To enhance the reliability of our study, we conducted expression validation in liver cancer. Validation of PPIA upregulation in liver cancer was carried out in 10 independent cohorts from the GEO database (Fig. 2D). We conducted WB and qPCR validation in one normal liver cell line and three liver cancer cell lines, and the results indicated significant upregulation of PPIA in liver cancer (Fig. 2E-F). Further analysis using the DepMap database examined the impact of PPIA knockdown on the viability of pan-cancer cell lines, revealing dependency scores below 0.5 in most cancer cell lines, suggesting that PPIA knockdown can inhibit the viability of these cancer cell lines (Figure S1).

Abnormal expression of PPIA in pan-cancer. (A,B) Box plots compare the expression levels of PPIA mRNA in tumor tissues (yellow) and normal tissues (blue) from the TCGA and GTEx databases. The statistical method used is the Wilcoxon rank sum test. (C) The heatmap compares the expression levels of PPIA transcripts in tumor and normal tissues from the combined TCGA and GTEx databases. Blue, orange, and white squares indicate downregulation, upregulation, and no difference in tumor tissues, respectively. The statistical method used is the Wilcoxon rank sum test. (D) Box plots compare the expression levels of PPIA mRNA in liver cancer tissues (yellow) and normal tissues (blue) from the GEO database. The statistical method used is the Wilcoxon rank sum test. (E) WB validates the protein expression level of PPIA in liver cancer cell lines. (F) qPCR validates the relative expression level of PPIA in liver cancer cell lines. Symbols *, **, and *** denote P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively.

Distribution of PPIA expression in single-cell transcriptome across pan-cancer

After conducting initial analysis on the expression of PPIA across pan-cancer, we found that it exhibits dysregulated states in most tumors, predominantly manifesting as upregulated expression. To gain deeper insights into the cell-specific expression patterns of PPIA in different cancers, we further analyzed single-cell transcriptome data. The results indicated that PPIA is widely distributed across different cell groups in various cancer types, yet its expression patterns vary among cancer cells (Fig. 3). For instance, in COAD, ESCA, and LUAD, PPIA mainly distributes in epithelial cells and keratinocytes, while in KIRC, LIHC, and LAML, its expression is potentially concentrated in immune cell populations. This differentiated expression distribution suggests that PPIA may play diverse roles in the tumor microenvironment and might be associated with specific biological behaviors of cancers.

Prognostic and diagnostic value of PPIA in pan-cancer

To explore the prognostic role of PPIA in various cancers, we used univariate Cox regression and KM survival analysis to assess the correlation of PPIA with four prognostic outcomes, including OS, DSS, DFI, and PFI. The results showed that high expression of PPIA is associated with poor prognosis in ACC, BLCA, BRCA, HNSC, KICH, LGG, LIHC, LUAD, MESO, PAAD, PRAD, SARC, SKCM, TGCT, and UVM, whereas it is associated with better prognosis in DLBC and THYM (Fig. 4A). Forest plots and KM survival curves detail the prognostic information (Fig. S2-3). To better understand the association between PPIA and clinical characteristics of cancer patients, we analyzed the expression differences of PPIA across different ages, TMN stages, and tumor stages. The results indicated that PPIA is correlated with clinical characteristics in some cancers. For instance, in ACC, KICH, LIHC, LUAD, and TGCT, higher stage corresponds to higher PPIA expression, whereas in KIRC and SKCM, the opposite is true (Fig. 4B). Diagnostic ROC analysis based on expression data from TCGA combined with GTEx cohorts showed that PPIA had an AUC greater than 0.9 in various cancers, indicating high diagnostic efficacy (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that PPIA is a potential molecular marker for predicting cancer prognosis and diagnosis.

Prognostic and Diagnostic Value of PPIA in Pan-Cancer. (1) Univariate Cox regression analysis and KM survival analysis were used to explore the correlation between PPIA expression and OS, DSS, DFI, and PFI. Red squares indicate PPIA as a prognostic risk factor, while blue squares indicate PPIA as a prognostic beneficial factor. (2) The heatmap shows the correlation analysis between PPIA expression and clinical characteristics. Blue, red, white, and gray squares represent negative correlation, positive correlation, no correlation, and missing data, respectively. (3) The forest plot presents the ROC analysis of PPIA expression for cancer diagnostic efficacy.

Immune characteristics of PPIA in the pan-cancer microenvironment

The development of malignant tumors is closely related to the immune microenvironment in which tumor cells reside. To further analyze the impact of PPIA on the immune status across pan-cancer, we used the “CIBERSORT,” “ssGSEA,” and “ESTIMATE” algorithms to assess the correlation between immune cell infiltration and PPIA. Overall, PPIA is closely related to the immune cell infiltration status of most cancers (Fig. 5A-C). PPIA is negatively correlated with most immune cells, such as B cells, T cells, and Th17 cells, but positively correlated with these cells in THYM. Certain cell subgroups are positively correlated in most cancers, such as Th2 cells, activated CD4 memory T cells, and Macrophages M0. The ESTIMATE algorithm showed that PPIA expression is negatively correlated with the immune score, estimate score, and stromal score in most cancers. Previous studies confirmed that the CypA protein encoded by PPIA can regulate the T cell-specific tyrosine kinase Itk for interleukin-2 and mediate intracellular signaling pathways for T cell activation51. When mutation of Itk disrupts binding with PPIA, it specifically increases the secretion of Th2 cell cytokines52.

Furthermore, there is also a correlation between PPIA expression and MHC, as well as immune checkpoints, although these correlations vary among different cancers and molecules (Figure S4). For example, it is positively correlated with MHC molecules in OV and SARC, and negatively correlated in ESCA, SKCM, and THYM. This suggests that PPIA may be related to tumor immune evasion mechanisms. These findings reveal dynamic interactions between PPIA expression and specific components of the tumor microenvironment in different cancer types. For instance, in THYM, PPIA expression is positively correlated with certain anti-tumor immune cells and negatively correlated with MHC molecules, which may be related to the complexity and dynamics of the tumor immune microenvironment. Studies have shown that MHC molecules do not always positively select T cells in the thymus53. Additionally, some thymic T cells (such as γδT cells) possess natural anti-tumor activity, with development dependent on specific signals in the thymic cortex, potentially independent of antigen presentation mediated by classical MHC molecules54.

Immune Characteristics of PPIA in the Tumor Microenvironment. (A,C) The ssGSEA algorithm (A), CIBERSORT algorithm (B), and ESTIMATE algorithm (C) were used to assess the correlation between immune cell infiltration and PPIA mRNA expression. Red squares indicate positive correlation, while blue squares indicate negative correlation, with deeper colors representing stronger correlations. Symbols *, **, and *** denote P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively.

Correlation between PPIA and pan-cancer genetic alterations

Gene mutations play a crucial role in cancer regulation. Additionally, TMB and MSI influence the response of cancers to immunotherapy. Tumor mutational burden assessment shows that PPIA expression is positively correlated with TMB in cancers such as THYM, KICH, and UCS, while it is inversely correlated in COAD (Figure S5). Microsatellite instability analysis also shows some associations with PPIA, such as in cancers like HNSC, KIRC, and LIHC (Figure S5), suggesting that PPIA may be related to DNA repair mechanisms or genomic stability and may influence the occurrence and development of tumors.

RNA modifications can affect mRNA stability, translation efficiency, splicing, and localization. In various cancers, the abnormal expression of RNA modification enzymes is closely associated with tumor occurrence, development, and metastasis, with some RNA modification enzymes potentially serving as cancer biomarkers. Our analysis indicates that the expression of PPIA is correlated with the expression of several RNA modification enzymes (including m1A, m5C, m6A) (Fig. 6A). For instance, in the m5C modification of most cancer types, NOP2, NSUN5, ALYREF, and YBX1, which perform “writer” and “reader” functions, are positively correlated with PPIA, while TET1, TET2, and TET3, which perform “eraser” functions, are negatively correlated with PPIA. This suggests that PPIA expression is positively correlated with m5C modification in pan-cancer.

DNA methylation is also a common epigenetic modification. Generally, methylation site levels in genic regions are positively correlated with gene expression, while increased methylation levels in gene promoter regions usually inhibit the transcription process, thereby affecting gene expression. Our study discovered 16 methylation sites correlated with PPIA expression (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, some methylation sites exhibit expression trends opposite to what is expected, such as the cg06436997 site in the gene transcription start region being positively correlated with PPIA. This might be related to the complex regulatory mechanisms of methylation, such as transcription factor binding preferences, uneven CpG island methylation, and the methylation paradox phenomenon, allowing genes to be effectively transcribed and expressed even under high methylation conditions.

Analysis of Genetic Alterations. (A) The heatmap illustrates the correlation between PPIA mRNA expression and mRNA expression of RNA modification genes (including m1A, m5C, m6A). Spearman correlation analysis was used for statistical evaluation. (B) The heatmap shows the correlation between PPIA mRNA expression and DNA methylation sites. Spearman correlation analysis was employed for statistical evaluation. Symbols *, **, and *** denote P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively.

Analysis of potential drugs targeting PPIA

To explore potential drugs that can target PPIA, we collected the top 100 upregulated genes with the most significant differences in each cancer from pan-cancer differential analysis and performed correlation analysis with perturbation gene expression data from the CMAP database. We selected the top 30 negatively correlated compounds, which may reverse the expression trends of differential genes in cancer (Fig. 7A). We also evaluated the relationship between PPIA and the response to anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy, finding that the group with a response to immunotherapy had higher PPIA expression levels compared to the non-responsive group (Fig. 7B). Additionally, we screened FDA-approved and clinically validated drugs from the CellMiner database for analysis, and the results showed that the sensitivity of 16 anti-tumor drugs was positively correlated with PPIA, indicating that patients with higher PPIA expression are more sensitive to these drugs (Figure S6).

Pan-cancer enrichment analysis

To further explore the potential biological functions of PPIA’s extensive involvement in cancer occurrence and development, we divided cancer samples into high and low PPIA expression groups, then performed differential gene expression analysis and GSEA analysis. In KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, various cancers are enriched in genome stability-related pathways such as DNA replication, Mismatch repair, and Base excision repair and are in an activated state. Meanwhile, enrichment in cancer-related pathways such as Calcium signaling pathway, cAMP signaling pathway, and Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction shows a suppressed state (Fig. 8A). In the Hallmark analysis, cell cycle-related pathways are significantly activated in various cancers, including G2M_CHECKPOINT and E2F_TARGETS. The activation of genome stability-related pathways may collectively contribute to uncontrolled proliferation in tumor cells, including DNA_REPAIR and MITOTIC_SPINDLE. Additionally, several cancer-related pathways are enriched, including KRAS_SIGNALING, MYC_TARGETS, INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE, and EPITHELIAL MESENCHYMAL TRANSITION (Fig. 8B). Previous studies have confirmed that PPIA can induce the transition of tumor cells from the G1 phase to the S phase to promote cell proliferation55. It can also regulate cell cycle-related proteins to enhance tumor cell proliferation12.

Enrichment Analysis in pan-cancer. (A) Based on the differential analysis results between high and low PPIA expression groups across 33 types of cancer, GSEA enrichment analysis was performed using the KEGG pathway gene set as a reference. (B) Similarly, GSEA enrichment analysis was conducted using the Hallmark gene set as a reference, based on the differential analysis results between high and low PPIA expression groups across 33 types of cancer. Red squares indicate pathways upregulated in the high PPIA expression group, blue squares indicate pathways downregulated, and white squares indicate pathways not enriched.

Discussion

PPIA, a key molecule involved in diverse biological functions such as molecular chaperoning, protein folding/transport, immune regulation, and cell signaling, is strongly implicated in cancer development and progression. Although previous studies established PPIA dysregulation in breast, esophageal, and pancreatic cancers, its broader roles and molecular characteristics across pan-cancer remained unclear. Our combined TCGA and GTEx data analysis revealed widespread PPIA dysregulation in most cancer types. Excluding MESO and UVM (lacking normal tissue data), only KICH and PCPG showed no significant expression differences. Significantly, PPIA was upregulated in the vast majority of cancers, with downregulation observed only in LAML. These findings strongly suggest a potential oncogenic role for PPIA across cancers. We further observed differential expression among PPIA transcripts. Protein-coding transcripts were frequently upregulated in multiple cancers. Notably, one NMD transcript of PPIA was upregulated in most cancers, possibly indicating NMD escape. Given that the hypoxic tumor microenvironment can inhibit NMD56, this finding warrants further investigation. Single-cell analysis confirmed PPIA’s broad expression across cell types, including macrophages. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are key drivers of pro-tumorigenic inflammation and progression57, potentially linking PPIA expression within these cells to its oncogenic role.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) comprises diverse components58. As research shows, the activation states and spatial distribution of immune cells within the TME significantly impact treatment efficacy59]– [60. Therefore, identifying predictive biomarkers and understanding immune infiltration status are essential for personalized immunotherapy. Our study reveals that PPIA expression correlates significantly with immune cell infiltration in pan-cancer analyses. Notably, PPIA predominantly showed negative correlations with anti-tumor immune cells like CD8 + T cells and NK cells. However, positive correlations were observed with pro-tumorigenic cells such as Th2 cells61. Intriguingly, certain cancers exhibited distinct patterns; for example, PPIA positively correlated with CD8 + T cells in THYM but negatively with Th2 cells in THCA. This variability likely stems from TME complexity and tumor heterogeneity, where specific immune contexts can alter cell function—recent studies even suggest Th2 cells may promote tumor growth62. Furthermore, PPIA expression associated with key immune regulatory genes, including immunosuppressive immune checkpoints (exploited by tumors to evade immunity and key therapeutic targets)63 and MHC molecules (core to antigen presentation and immune activation, enhancing checkpoint inhibitor efficacy)64. Collectively, our findings highlight PPIA’s widespread relevance in the pan-cancer immune landscape, advancing understanding of its role in cancer immune dysregulation.

Genetic alterations, including mutations, rearrangements, amplifications, and deletions, drive cancer initiation, progression, and treatment response by disrupting normal cellular controls65]– [66. In immunotherapy, TMB and MSI are key predictors of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors, with higher levels generally indicating greater immunogenicity and favorable outcomes67]– [68. Significantly, our analysis links PPIA expression to TMB in 18 cancer types and MSI in 14 types. These associations highlight PPIA’s connection to the tumor microenvironment and its potential as an immunotherapy biomarker in specific cancers. Beyond genetics, epigenetic mechanisms—notably RNA modifications—profoundly influence cancer by regulating gene expression and cellular functions, presenting promising therapeutic targets69]– [70. PPIA demonstrates significant correlations with multiple RNA modification regulators (m6A, m5C, m1A) across cancers. Intriguingly, PPIA frequently correlates positively with m5C “writers” (e.g., NOP2, NSUN5) and “readers” (e.g., ALYREF, YBX1), but negatively with “erasers” (TET1-3). This pattern suggests PPIA may cooperate with writers/readers to modulate mRNA stability, translation, or degradation, thereby influencing tumor progression. PPIA is also linked to DNA methylation—another key epigenetic alteration71. Promoter hypermethylation often silences genes72, while gene body methylation can promote activation/maintenance73.

To elucidate PPIA’s functional mechanisms across cancers, we performed GSEA. We found that PPIA is broadly associated with pathways related to genomic stability and the cell cycle. These results indicate that PPIA is associated with numerous oncogenic mechanisms: dysregulated proliferation, persistent DNA damage stress, and adaptive repair activation, collectively fueling tumor progression and therapy resistance74. Enrichment of E2F targets and G2/M checkpoint activation are hallmarks of aberrant cell cycle control in cancer. Normally, E2F activity is tightly restrained by Rb and confined to G1/S transition. However, Rb pathway inactivation in tumors leads to constitutive E2F activation, driving unscheduled S-phase gene expression and uncontrolled proliferation75. While DNA damage typically activates the G2/M checkpoint to halt division, this function is frequently impaired in TP53-mutant tumors. Consequently, cells enter mitosis with unrepaired DNA, exacerbating genomic instability76. This paradoxical activation yet functional deficiency of the checkpoint may represent adaptive tumor evolution. Upregulated DNA replication pathways indicate heightened replication stress, commonly induced by oncogenes (e.g., MYC, RAS—whose targets were also enriched). Oncogene-driven proliferation stalls replication forks and causes double-strand breaks, triggering ATM/ATR-mediated repair77. Persistent stress, however, can overwhelm repair capacity, leading to chromosomal aberrations. The concurrent upregulation of DNA repair mechanisms suggests tumors counteract chronic DNA damage. While potentially delaying early transformation, these repair pathways may be co-opted in advanced cancers to sustain genomic integrity and survival78.

While our study elucidates the role of PPIA in pan-cancer from multiple dimensions and cohorts, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, the research primarily relies on data obtained from public databases and statistical analyses. While integrating multiple cohorts strengthens generalizability, it inevitably introduces heterogeneity stemming from diverse sources. Crucially, differences in sample processing protocols, sequencing platforms, and inherent biases within individual databases could lead to systematic variations in gene expression quantification and other molecular measurements. Consequently, the results derived from these bioinformatics analyses should be interpreted with appropriate caution regarding this inherent technical and batch variation. Secondly, correlation analysis cannot demonstrate causality, and the impact of PPIA on tumor progression lacks sufficient experimental validation. However, the related findings indicate directions for future research. In summary, our research demonstrates that PPIA is significantly upregulated in most cancers and is closely associated with cancer prognosis, the immune microenvironment, and epigenetic modifications. These findings warrant further in-depth exploration in future studies.

Data availability

The datasets utilized and analyzed in this study are accessible from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/, TCGA-LIHC) and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73(1), 17–48 (2023).

Lu, J., Ding, J., Liu, Z. & Chen, T. Retrospective analysis of the Preparation and application of immunotherapy in cancer treatment (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 60(2), 12 (2022). [pii].

Pang, J. et al. Multiomics analysis reveals the involvement of NET1 in tumour immune regulation and malignant progression. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 56 (2025).

Srivastava, S. & Hanash, S. Pan-Cancer early detection: hype or hope. Cancer Cell. 38(1), 23–24 (2020).

Handschumacher, R. E., Harding, M. W., Rice, J., Drugge, R. J. & Speicher, D. W. Cyclophilin: a specific cytosolic binding protein for cyclosporin A. Science 226, 544–547 (1984).

Ren, Y. X. et al. CD147 stimulates hepatoma cells escaping from immune surveillance of T cells by interaction with Cyclophilin A. Biomed Pharmacother 80, 289–297 (2016).

Bram, R. J., Hung, D. T., Martin, P. K., Schreiber, S. L. & Crabtree, G. R. Identification of the Immunophilins capable of mediating Inhibition of signal transduction by cyclosporin A and FK506: roles of calcineurin binding and cellular location. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 4760–4769 (1993).

Colgan, J., Asmal, M., Yu, B. & Luban, J. Cyclophilin A-deficient mice are resistant to immunosuppression by cyclosporine. J. Immunol. 174, 6030–6038 (2005).

Bauer, K. et al. Cyclophilins contribute to Stat3 signaling and survival of multiple myeloma cells. Oncogene 28, 2784–2795 (2009).

Sun, S. et al. Cyclophilin A (CypA) interacts with NF-κB subunit, p65/RelA, and contributes to NF-κB activation signaling. PLoS One. 9, e96211 (2014).

Sun, S. et al. Knockdown of CypA inhibits interleukin-8 (IL-8) and IL-8-mediated proliferation and tumor growth of glioblastoma cells through down-regulated NF-κB. J. Neurooncol. 101, 1–14 (2011).

Li, L. et al. HAb18G/CD147 promotes pSTAT3-mediated pancreatic cancer development via CD44s. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 6703–6715 (2013).

Lu, W. et al. PPIA dictates NRF2 stability to promote lung cancer progression. Nat. Commun. 15, 4703 (2024).

Sun, K., Hong, J. J., Chen, D. M., Luo, Z. X. & Li, J. Z. Identification and validation of necroptosis-related prognostic gene signature and tumor immune microenvironment infiltration characterization in esophageal carcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol. 22, 344 (2022).

Liu, J., Wang, Y., Zhao, Z. & Ge, Y. Bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation of tumorigenic role of PPIA in gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 13, 19116 (2023).

Tomczak, K., Czerwińska, P. & Wiznerowicz, M. The Cancer genome atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp. Oncol. (Pozn). 19, A68–77 (2015).

Goldman, M. J. et al. Visualizing and interpreting cancer genomics data via the Xena platform. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 675–678 (2020).

Chen, Y., Pal, B., Lindeman, G. J., Visvader, J. E. & Smyth, G. K. R code and downstream analysis objects for the scRNA-seq atlas of normal and tumorigenic human breast tissue. Sci. Data. 9, 96 (2022).

Zhang, M. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic architecture and intercellular crosstalk of human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 73, 1118–1130 (2020).

Uhlitz, F. et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase activity drives cell trajectories in colorectal cancer. EMBO Mol. Med. 13, e14123 (2021).

Shi, K. et al. Profiling transcriptional heterogeneity of epithelium, fibroblasts, and immune cells in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by single-cell RNA sequencing. FASEB J. 36, e22620 (2022).

Ruffin, A. T. et al. B cell signatures and tertiary lymphoid structures contribute to outcome in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 12, 3349 (2021).

Borcherding, N. et al. Mapping the immune environment in clear cell renal carcinoma by single-cell genomics. Commun. Biol. 4, 122 (2021).

Lu, Y. et al. A single-cell atlas of the multicellular ecosystem of primary and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 13, 4594 (2022).

Bailur, J. K. et al. Risk-associated alterations in marrow T cells in pediatric leukemia. JCI Insight. 5, e140179 (2020).

Laughney, A. M. et al. Regenerative lineages and immune-mediated pruning in lung cancer metastasis. Nat. Med. 26, 259–269 (2020).

Xu, J. et al. Single-Cell RNA sequencing reveals the tissue architecture in human High-Grade serous ovarian Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 3590–3602 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. IL-1β is an Androgen-Responsive target in macrophages for immunotherapy of prostate Cancer. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 10, e2206889 (2023).

Jeong, H. Y. et al. Spatially distinct reprogramming of the tumor microenvironment based on tumor invasion in Diffuse-Type gastric cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 6529–6542 (2021).

Pan, J. et al. Papillary thyroid carcinoma landscape and its immunological link with Hashimoto thyroiditis at Single-Cell resolution. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 758339 (2021).

Fonseca-Montaño, M. A., Blancas, S. & Herrera-Montalvo, L. A. Hidalgo-Miranda, A. Cancer genomics. Arch. Med. Res. 53, 723–731 (2022).

Roessler, S. et al. A unique metastasis gene signature enables prediction of tumor relapse in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer Res. 70, 10202–10212 (2010).

Lim, H. Y. et al. Prediction of disease-free survival in hepatocellular carcinoma by gene expression profiling. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 20, 3747–3753 (2013).

Wang, H. W. et al. Forfeited hepatogenesis program and increased embryonic stem cell traits in young hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) comparing to elderly HCC. BMC Genom. 14, 736 (2013).

Villa, E. et al. Neoangiogenesis-related genes are hallmarks of fast-growing hepatocellular carcinomas and worst survival. Results from a prospective study. Gut 65, 861–869 (2016).

Villanueva, A. et al. DNA methylation-based prognosis and epidrivers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 61, 1945–1956 (2015).

Grinchuk, O. V. et al. Tumor-adjacent tissue co-expression profile analysis reveals pro-oncogenic ribosomal gene signature for prognosis of resectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Oncol. 12, 89–113 (2018).

Shimada, S. et al. Comprehensive molecular and immunological characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma. EBioMedicine 40, 457–470 (2019).

Wang, S. M., Ooi, L. L. & Hui, K. M. Identification and validation of a novel gene signature associated with the recurrence of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 6275–6283 (2007).

Tsherniak, A. et al. Defining a Cancer dependency map. Cell 170, 564–576e16 (2017).

Liu, J. et al. An integrated TCGA Pan-Cancer clinical data resource to drive High-Quality survival outcome analytics. Cell 173, 400–416e11 (2018).

Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 14, 7 (2013).

Bindea, G. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity 39, 782–795 (2013).

Chen, B., Khodadoust, M. S., Liu, C. L., Newman, A. M. & Alizadeh, A. A. Profiling tumor infiltrating immune cells with CIBERSORT. Methods Mol. Biol. 1711, 243–259 (2018).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612 (2013).

Thorsson, V. et al. The immune landscape of Cancer. Immunity 48, 812–830e14 (2018).

Mariathasan, S. et al. TGFβ attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 Blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature 554, 544–548 (2018).

Reinhold, W. C. et al. CellMiner: a web-based suite of genomic and Pharmacologic tools to explore transcript and drug patterns in the NCI-60 cell line set. Cancer Res. 72, 3499–3511 (2012).

Liberzon, A. et al. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell. Syst. 1, 417–425 (2015).

Tan, K., Stupack, D. G. & Wilkinson, M. F. Nonsense-mediated RNA decay: an emerging modulator of malignancy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 22, 437–451 (2022).

Brazin, K. N., Mallis, R. J., Fulton, D. B. & Andreotti, A. H. Regulation of the tyrosine kinase Itk by the peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Cyclophilin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 99, 1899–1904 (2002).

Colgan, J. et al. Cyclophilin A regulates TCR signal strength in CD4 + T cells via a proline-directed conformational switch in Itk. Immunity 21, 189–201 (2004).

Klein, L., Kyewski, B., Allen, P. M. & Hogquist, K. A. Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: what thymocytes see (and don’t see). Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 377–391 (2014).

Mensurado, S., Blanco-Domínguez, R. & Silva-Santos, B. The emerging roles of γδ T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 178–191 (2023).

Gong, Z. et al. Cyclophilin A is overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma and is associated with the cell cycle. Anticancer Res. 37, 4443–4447 (2017).

Wang, D. et al. Inhibition of nonsense-mediated RNA decay by the tumor microenvironment promotes tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 3670–3680 (2011).

Mantovani, A., Marchesi, F., Malesci, A., Laghi, L. & Allavena, P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 14, 399–416 (2017).

Shiao, S. L., Chu, G. C. & Chung, L. W. Regulation of prostate cancer progression by the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 380(1), 340–348 (2016).

Binnewies, M. et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat. Med. 24(5), 541–550 (2018).

Wu, T. & Dai, Y. Tumor microenvironment and therapeutic response. Cancer Lett. 387, 61–68 (2017).

Chraa, D., Naim, A., Olive, D. & Badou, A. T lymphocyte subsets in cancer immunity: friends or foes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 105(2), 243–255 (2019).

Wang, B. et al. CD4 + T helper 2 cell-macrophage crosstalk induces IL-24-mediated breast cancer suppression. JCI Insight. 10(1), e180962 (2025).

Topalian, S. L., Drake, C. G. & Pardoll, D. M. Immune checkpoint blockade: a common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 27(4), 450–461 (2015).

Lind, H. T. et al. MHC class I upregulation contributes to the therapeutic response to radiotherapy in combination with anti-PD-L1/anti-TGF-β in squamous cell carcinomas with enhanced CD8 T cell memory-driven response. Cancer Lett. 608, 217347 (2025).

Romei, C. & Elisei, R. A narrative review of genetic alterations in primary thyroid epithelial Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(4), 1726 (2021).

Herceg, Z. & Hainaut, P. Genetic and epigenetic alterations as biomarkers for cancer detection, diagnosis and prognosis. Mol. Oncol. 1(1), 26–41 (2007).

Manca, P. et al. Tumour mutational burden as a biomarker in patients with mismatch repair deficient/microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal cancer treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur. J. Cancer. 187, 15–24 (2023).

Yin, X. et al. Potential predictive biomarkers in antitumor immunotherapy: navigating the future of antitumor treatment and immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy. Front. Oncol. 14, 1483454 (2024).

Kim, H. S., Eun, J. W., Jang, S. H., Kim, J. Y. & Jeong, J. Y. The diverse landscape of RNA modifications in cancer development and progression. Genes Genomics (2024).

Liu, Y., Zhang, S., Liu, K., Gu, X. & Hu, X. RNA modification and digestive tract tumors: A review. Curr. Med. Chem. (2025).

Mehdi, A. & Rabbani, S. A. Role of methylation in Pro- and Anti-Cancer immunity. Cancers (Basel). 13(3), 545 (2021).

Fu, S., Debes, J. D. & Boonstra, A. DNA methylation markers in the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 191, 112960 (2023).

Greenberg, M. & Bourc’his, D. The diverse roles of DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20(10), 590–607 (2019).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 (2011).

Chen, H. Z., Tsai, S. Y. & Leone, G. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 9, 785–797 (2009).

Kastenhuber, E. R. & Lowe, S. W. Putting p53 in context. Cell 170, 1062–1078 (2017).

Zeman, M. K. & Cimprich, K. A. Causes and consequences of replication stress. Nat. Cell. Biol. 16, 2–9 (2014).

Brown, J. S., O’Carrigan, B., Jackson, S. P. & Yap, T. A. Targeting DNA repair in cancer: beyond PARP inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 7, 20–37 (2017).

Funding

This work was supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82274323), Key Research and Development Project of the Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Grant No. 2024YFFK0150).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y. and X.G. performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. H.L. designed the research study. H.L. and Y. Y. assisted with data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.Y.Y. and X.G. performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. H.L. designed the research study. H.L. and Y. Y. assisted with data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, Y., Gong, X. & Li, H. Multidimensional pan-cancer analysis reveals the impact of PPIA on tumor epigenetic modifications and immune regulation. Sci Rep 15, 20988 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05997-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05997-9