Abstract

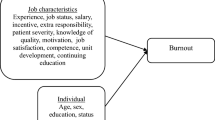

Nurses are highly susceptible to job burnout, which can negatively impact both their well-being and the quality of patient care. Addressing this issue is crucial for maintaining an effective healthcare workforce. Although some research has indicated a connection between job burnout and an intolerance of uncertainty, the fundamental mechanisms of this association have not been investigated. This study aims to fill this gap by exploring the underlying pathways through which intolerance of uncertainty influences job burnout, providing insights for targeted interventions. For the questionnaire survey, 857 clinical nurses were selected using a convenience selection method. Resilience, change fatigue, job burnout, and intolerance of uncertainty were measured by the IUS-12, CF, CD-RISC, and CMBI, respectively. In this study, structural equation modeling was employed to analyze the direct and indirect effects among these variables, with model fit indices ensuring statistical robustness. Bootstrapping was used to test the significance of mediation effects, enhancing the reliability of the findings. Change fatigue and resilience, respectively, acted as mediators in the relationship between job burnout and intolerance of uncertainty. Resilience and change fatigue served as chain mediators between intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout (total mediating effect = 0.320, effect percentage = 42.2%). To mitigate job burnout, nursing managers should implement specific measures, such as resilience-building training programs, stress management workshops, and initiatives to improve team support and communication. These interventions should be designed to alleviate change fatigue and enhance resilience, thus reducing burnout levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Clinical nurses constantly work in high-pressure and high-stress environments, facing numerous unique occupational stressors1,2. One of the primary sources of stress is long-term shift work3. Night shifts, extended working hours, and frequent shift rotations disrupt nurses’ circadian rhythms, adversely affecting their physical and mental well-being4,5. In addition to performing physically demanding nursing tasks, nurses must also address the emotional needs of patients and their families6further intensifying their emotional burden. Moreover, their work is often filled with sudden emergency cases and unpredictable critical situations7exacerbating their overall job stress. As a result, nurses are at a heightened risk of experiencing job burnout8.

Surveys carried out in China indicate that between 50% and 60% of nurses experience job burnout9,10. Job burnout has not only become a common phenomenon in the workplace, it has even developed into a disease11. Studies have shown that prolonged, unresolved job burnout can disrupt the complex neural and hormonal systems that regulate sleep12,13. The release of stress hormones can lead to adverse symptoms, including migraines, loss of appetite, and changes in eating habits14,15,16. A study in Italy found that among frontline healthcare workers experiencing job burnout, 55% reported difficulty sleeping, and nearly 40% frequently had nightmares17. Job burnout can also impair attention, memory, and coping abilities, leading to anxiety, irritability, and depressive symptoms18,19. A study on teachers revealed that 86–90% of those experiencing job burnout met the diagnostic criteria for depression20. Andela’s research confirmed a correlation between job burnout and suicidal ideation21. Job burnout not only causes physical and mental harm to nurses but also reduces their work efficiency, enthusiasm, quality of care, and professional identity22,23.

Therefore, alleviating job burnout among nurses to ensure high-quality patient care has become a key focus for researchers. While existing studies have explored the causes of job burnout and its impact on individuals, they have yet to fully uncover the job burnout mechanisms specific to nurses working in uncertain environments. The rapid transformations and complexities of modern healthcare systems expose nurses to a high degree of uncertainty24. However, individuals vary in their tolerance for uncertainty, which may contribute to differences in job burnout levels25. Thus, understanding how intolerance of uncertainty affects job burnout among nurses is crucial. Moreover, current research has rarely examined the internal mechanisms of this process from the perspectives of resilience and change fatigue, despite these factors playing a critical role in job burnout. Resilience is considered a vital psychological resource that helps individuals cope with stress and mitigate the negative effects of uncertainty, whereas change fatigue may exacerbate these effects26. Investigating the roles of resilience and change fatigue in the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout will not only deepen our understanding of the underlying mechanisms but also provide more targeted intervention strategies for clinical nursing management. Therefore, this study aims to bridge this research gap.

Intolerance of uncertainty refers to an individual’s negative beliefs about uncertain factors and a tendency to perceive the unknown as a source of stress27. As the modern healthcare system undergoes continuous adjustments, optimizations, and innovations, the work environment in the medical field inherently involves a certain degree of uncertainty24. In such an uncertain environment, individuals with low tolerance for uncertainty are more likely to perceive it as a stressor, making them more susceptible to feelings of burnout28. A study on frontline healthcare workers found that those with higher intolerance of uncertainty were more prone to experiencing symptoms of job burnout29. Based on this, the present study proposes the following hypothesis: H1: Intolerance of uncertainty is significantly and positively correlated with job burnout among nurses.

Resilience refers to an individual’s psychological capacity to effectively cope, adapt, and recover when faced with stress, challenges, trauma, or adversity30. It not only reflects the ability to bounce back from difficulties but also encompasses personal growth and the capacity to adapt to future challenges after experiencing setbacks30,31. Resilience is a key factor in maintaining psychological stability and responding positively to uncertainty and stress30. Dugas proposed that intolerance of uncertainty is a form of “cognitive bias” that influences an individual’s emotional and behavioral responses32. This cognitive bias makes individuals more prone to anxiety when facing uncertainty, thereby reducing their resilience32. Additionally, a study by Dalzel found that enhancing nurses’ resilience through training significantly reduced their levels of job burnout33. These findings suggest a potential relationship between intolerance of uncertainty, resilience, and job burnout. Based on this, the present study proposes the following hypothesis: H2: Resilience mediates the relationship between nurses’ intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout.

Change fatigue refers to the emotional and psychological exhaustion experienced by individuals due to continuous and frequent workplace changes. It manifests as feelings of powerlessness, numbness, and even resistance to change34. With the ongoing reforms in the healthcare system, nurses are required to adjust their traditional work routines and restructure the methods and approaches used to provide patient care. As a result, they may struggle to adapt to these changes35,36. Nurses with higher intolerance of uncertainty are more likely to perceive change as a threat, increasing their risk of experiencing change fatigue37. Research has shown that change fatigue not only intensifies nurses’ work-related stress but may also be a significant contributing factor to job burnout38. Huynh et al.‘s research of 119 personnel (including 54 nurses and 65 physicians) in a teaching hospital discovered that nurses had the highest levels of change fatigue and job burnout39. Moreover, the higher the level of change fatigue, the more severe the job burnout39,40. Despite this, there is still limited research on change fatigue, particularly among nurses. Thus, there is also a connection between intolerance of uncertainty, change fatigue, and job burnout. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis: H3: Change fatigue mediates the relationship between nurses’ intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout.

According to the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, individuals cope with stress and challenges by protecting their key resources26. The uncertainty and job burnout experienced by nurses are closely related to resource depletion and exhaustion. Resilience is considered a critical psychological resource for managing uncertainty and stress, whereas change fatigue reflects a state of resource depletion26. Resilience enables nurses to adopt positive coping strategies, mitigating the negative impact of uncertainty and reducing the risk of job burnout. In contrast, change fatigue further weakens nurses’ ability to cope with stress, intensifying the effect of uncertainty on job burnout. Together, these two factors influence the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout among nurses. Based on this, the present study proposes the following hypothesis: H4: Resilience and change fatigue jointly mediate the relationship between nurses’ intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout.

In summary, this study aims to explore the relationships among nurses’ intolerance of uncertainty, resilience, change fatigue, and job burnout, as well as the potential mediating roles of resilience and change fatigue in these relationships. By uncovering the complex mechanisms underlying these variables, this research seeks to contribute to the theoretical understanding of job burnout. Furthermore, the findings will provide a scientific basis for healthcare institutions to develop targeted interventions for reducing job burnout among nurses, ultimately enhancing their well-being and improving the quality of patient care.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study conducted a cross-sectional survey from October 2023 to February 2024 by administering an online questionnaire to nurses working at the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medical University, the Third Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medical University, and Jinzhou Central Hospital in Liaoning Province, China. The inclusion criteria were as follows: nurses aged 18 years or older, holding a valid nursing license and voluntarily agreeing to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were: nurses in training, intern nurses, nurses who had been employed for less than one year, and nurses who were retired or had left their positions. Since the participants of this study were clinical nurses with high workloads and demanding schedules, implementing a purely random sampling method posed practical challenges. To improve the questionnaire response rate, ensure an adequate sample size, and enhance the feasibility of data collection, this study employed a convenience sampling method. Additionally, convenience sampling allowed for the rapid collection of real-time feedback from frontline clinical nurses, providing valuable insights into their psychological state under work-related uncertainty, thereby better aligning with the research objectives. However, this method may lead to limitations in sample representativeness and introduce potential bias. To mitigate these issues, the study implemented the following control measures: (1) An anonymous survey was conducted to minimize social desirability bias; (2) A mix of positively and negatively worded items was interspersed to reduce response pattern bias; (3) Harman’s one-way test was used to assess common method bias. If the variance explained by a single factor did not exceed 50%, the method bias was considered to be within an acceptable range41.

To determine the minimum sample size for this study, we conducted a power analysis using G*Power 3.1. The analysis was performed using a two-tailed test with a significance level of α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and an assumed medium effect size. The results indicated that the minimum required sample size was 128 for the t-test, 231 for ANOVA, and 84 for Pearson correlation analysis. Since G*Power does not directly calculate the required sample size for Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), we referred to established recommendations suggesting that the sample size should be at least 10–15 times the number of observed variables42. This study included 11 observed variables: Anticipatory Emotions, Anticipatory Behaviors, Inhibited Sexual Behaviors, Strength, Optimism, Tenacity, Change, Fatigue, Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Reduced Personal Accomplishment. Based on this guideline, the estimated required sample size ranged from 110 to 165. To account for an anticipated 20% rate of incomplete or invalid responses, the final required sample size was adjusted to 132–198. However, to enhance the robustness and precision of the results and to avoid potential model misfit due to insufficient sample size, a total of 900 questionnaires were distributed. After excluding incomplete responses and those with excessively short completion times, 857 valid questionnaires remained, yielding an effective response rate of 95.2%.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medical University (No. KYLL202401). In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, all participants provided informed consent and voluntarily participated in this study.

Measures

General demographic characteristics

After reviewing the literature, our team designed the questionnaire in consultation with experts. The questionnaire included 11 items: gender, age, educational level, marital status, years of experience as a nurse, work shift, employment type, position, title, department, and average monthly income (RMB).

Intolerance of uncertainty

We used the Chinese version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12 (IUS-12), translated and revised by Lijuan Wu et al., to assess intolerance of uncertainty43. This scale includes three dimensions—anticipatory emotions, anticipatory behaviours, and inhibited sexual behaviours—comprising a total of 12 items. Responses are rated on a 1 to 5 scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Higher scores indicate greater intolerance of uncertainty, meaning lower tolerance for uncertainty. The scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79 43.

Resilience

We used the Chinese version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), revised by Nan Xiao and Jianxin Zhang, to assess resilience44. The scale consists of 25 items and includes three dimensions: strength, optimism, and tenacity. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with ‘Never’ scoring 0 points and ‘Almost Always’ scoring 4 points. Higher scores indicate greater levels of psychological resilience. The scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.9144.

Change fatigue

We used the Chinese version of the Change Fatigue Scale (CF), translated and revised by our team, to assess change fatigue. This scale consists of 6 items and includes two dimensions: change and fatigue. Responses are rated on a 7-point Likert scale, with ‘Strongly Disagree’ scoring 1 point, ‘Neutral’ scoring 4 points, and ‘Strongly Agree’ scoring 7 points. Higher scores indicate more severe change fatigue. Our research team employed Brislin translation-back translation method to translate the original scale. To enhance linguistic accuracy and cultural adaptability, expert reviews and cognitive interviews were conducted to refine item wording. Following a small-scale pilot study, the final Chinese version of the scale was established, and its reliability and validity were further evaluated in an independent sample (N = 1,212). The results indicated that the scale demonstrated strong content validity, with a Scale Content Validity Index (S-CVI) of 0.958. Exploratory factor analysis supported a two-factor structure, accounting for 71.586% of the cumulative variance. Confirmatory factor analysis showed that the modified model had a good fit (χ²/df = 2.587, CFI = 0.991, TLI = 0.982, RMSEA = 0.051). Furthermore, the scale exhibited good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.802, split-half reliability of 0.736, and test-retest reliability of 0.861. Overall, these findings suggest that the scale possesses strong reliability and validity, making it a suitable tool for assessing the level of change fatigue among Chinese nurses.

Job burnout

We used the Chinese Maslach Burnout Inventory (CMBI), developed by Dr. Yongxin Li, to assess job burnout45. This scale includes 15 items across three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. It employs a 7-point Likert scale, with ratings ranging from ‘Strongly Disagree’ (1 point) to ‘Strongly Agree’ (7 points). The dimension of reduced personal accomplishment is scored inversely. The total score ranges from 15 to 105, with higher scores indicating greater job burnout severity. According to Yongxin Li’s classification, the critical values for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment are > 25, >11, and > 16, respectively. If scores on all three dimensions are below the critical values, there is no job burnout; if one dimension score exceeds the critical value, it indicates mild job burnout; if two dimensions exceed the critical value, it indicates moderate job burnout; and if all three dimensions exceed the critical values, it indicates severe job burnout. The scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88246.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 25.0. Descriptive statistics for categorical data were presented as frequencies and proportions, while continuous data were reported as means ± standard deviations. T-tests and ANOVA were used to examine differences in study variables across various demographic characteristics. Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the relationships between research variables. AMOS 24.0 software was used to construct a SEM based on theoretical hypotheses, incorporating latent variables (Intolerance of Uncertainty, Resilience, Change Fatigue, and Job Burnout) and their observed variables (dimension scores from respective scales). First, model identification was tested by examining the model’s degrees of freedom (df). If df > 0, the model was deemed identifiable. Next, model fit was assessed using various fit indices, including χ²/df, CFI, TLI, IFI, GFI, AGFI, SRMR, and RMSEA. A model was considered well-fitted if key fit indices met recommended thresholds (e.g., 1 < χ²/df < 5, CFI, TLI, IFI, GFI, and AGFI > 0.90, SRMR and RMSEA < 0.08). Finally, to further examine the mediation effects, the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method (with 5,000 resampling iterations) was used to calculate the 95% confidence interval (CI). If the 95% CI for a mediation path did not include zero, the mediation effect was considered statistically significant47. Figure 2 was created using https://www.chiplot.online/.

Results

Common method bias test

This study employed Harman’s one-way test to assess CMB. An exploratory factor analysis was conducted on all variables from the measurement scales used in this study. The unrotated principal component analysis identified nine factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, indicating a multifactor structure. The first factor accounted for 42.45% of the variance, which is below the critical threshold of 50% recommended by Podsakoff, suggesting that CMB was within an acceptable range41.

General demographic characteristics

The differences in job burnout among nurses with different educational levels, years of experience as a nurse, work shifts, positions, departments, and average monthly income (RMB) were statistically significant (P < 0.05). For more detailed information, shown in Table 1.

Variable score situation

The total job burnout score for nurses was 56.30 ± 15.79. This indicates that the nurses in the sample exhibit a moderately high level of job burnout. Among the dimensions of job burnout, emotional exhaustion had the highest average score. The scores for other variables are presented in Table 2. The prevalence of job burnout among nurses was 92.6%, with moderate job burnout being the most common, accounting for 51.3% of the total. This highlights the widespread issue of job burnout among the nursing population. As shown in Fig. 1.

Correlation analysis

The correlation analysis results show a strong positive correlation between intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout (r = 0.615, P < 0.01), confirming Hypothesis 1. Intolerance of uncertainty is moderately negatively correlated with resilience (r = −0.434, P < 0.01), indicating that higher intolerance of uncertainty is associated with lower resilience. Intolerance of uncertainty is also moderately positively correlated with Change fatigue (r = 0.492, P < 0.01), suggesting that nurses with higher intolerance of uncertainty are more likely to experience change fatigue. Resilience is strongly negatively correlated with both change fatigue (r = −0.637, P < 0.01) and job burnout (r = −0.613, P < 0.01), indicating that nurses with higher resilience are less likely to experience change fatigue and job burnout, suggesting that resilience may play a protective role in alleviating job burnout. Change fatigue is strongly positively correlated with Job burnout (r = 0.621, P < 0.01), meaning that the more severe the change fatigue, the higher the level of job burnout. This strong positive correlation suggests that change fatigue may be an important risk factor for exacerbating job burnout. As shown in Fig. 2.

Mediation analysis

The model identification test results show that df > 0 (df = 38), indicating that the model is identifiable. The model showed a good fit, with a χ²/df value of 4.367. Other fit indices are presented in Table 3. The structural equation model is illustrated in Fig. 3.

The bias-corrected percentile Bootstrap method was applied, with 5,000 resampling iterations, to test the mediation effect. The results showed that the 95% CI for the total effect, direct effect, and indirect effect from intolerance of uncertainty to job burnout do not include 0, with Z > 1.96 and P < 0.05. This indicates that all paths are statistically significant. The total effect from intolerance of uncertainty to job burnout is 0.759, with the direct effect being 0.439, accounting for 57.8%, and the indirect effect being 0.320, accounting for 42.2%. This indicates that the direct effect is the primary influencing path, though the indirect effect is also notable. Further analysis of the indirect effects shows that resilience alone has a mediating effect of 0.129 (17.0% of the total effect), supporting Hypothesis 2. The mediating effect of change fatigue alone is 0.103 (13.6%), supporting Hypothesis 3. The chain mediating effect of resilience → change fatigue is 0.089 (11.7%), supporting Hypothesis 4. As shown in Table 4.

Discussion

The current status of job burnout among nurses and its relationship with demographic variables

This study found that emotional exhaustion is the primary manifestation of job burnout among nurses, which is consistent with previous research48. This result may stem from the high emotional investment inherent in the nursing profession6 and the depletion of psychological resources in a long-term high-stress environment1. In this study, the proportion of nurses experiencing job burnout reached 92.6%, which is similar to the study by Gan et al.49but significantly higher than the nationwide survey by Qian et al. (average score of 44.84)50. The average score of job burnout in this study was about 25% higher. This difference may be related to work load, doctor-patient relationships, and the regional environment of the study subjects. Firstly, the high level of burnout in this study reflects the increasing pressure in nursing work in recent years. With the rising demand for healthcare services, nurses’ roles have shifted from traditional auxiliary care to more comprehensive patient management51. They are not only responsible for daily nursing tasks but also for providing psychological support and health education for patients2,52which may lead to higher levels of job burnout. Secondly, the high rate of job burnout in this study may be attributed to the specific work environment in the study area—Northeastern China. Previous studies have shown that nurses in Northeast China generally experience higher levels of job burnout, with Liaoning Province being a particularly high-risk area for burnout49. Possible reasons include: First, there is a serious shortage of nursing human resources in the Northeast, forcing nurses to endure higher work intensity, including frequent overtime and shift work53. Second, the relatively slow socio-economic development in Northeast China and inadequate distribution of medical resources54 may result in a larger gap between nurses’ expectations for career development and compensation, exacerbating job burnout. Third, the social culture in the Northeast emphasizes collectivism and a high commitment to professional responsibilities55which may intensify job burnout in nurses under high-pressure conditions. In conclusion, the main manifestation of job burnout in this study is consistent with previous research. However, there are differences in the levels of job burnout, reflecting the increasing pressure in the nursing industry in recent years, particularly in areas with relatively tight nurse resources. Therefore, future studies should focus more on regional differences to develop intervention strategies tailored to different areas, effectively alleviating nurses’ job burnout levels.

This study found that general demographic variables, including education level, years of experience as a nurse, work shift, position, department, and average monthly income, have a significant impact on nurses’ job burnout (P < 0.05). Firstly, nurses with less than 3 years of experience had the highest levels of job burnout. This may be due to the challenges that newly hired nurses face in adapting to the work environment, managing complex clinical situations, and addressing patient needs56leading to increased psychological stress57 and, consequently, a higher risk of burnout. Secondly, nurses working on work by turns shifts have significantly higher levels of job burnout compared to those on regular shifts. This suggests that irregular working hours may disrupt their biological clocks and degrade sleep quality5thus exacerbating job burnout4.

Furthermore, nurses in higher management positions reported relatively lower levels of job burnout, which may be related to greater work autonomy and more career development opportunities58. Nurses working in high-pressure environments such as the emergency department and intensive care unit had significantly higher levels of job burnout compared to nurses in outpatient departments and obstetrics and gynecology, reflecting the increased physical and psychological burden that high-intensity, high-risk work environments place on nurses. In addition, nurses with lower monthly incomes reported significantly higher levels of job burnout compared to those with higher incomes, indicating that compensation may affect job satisfaction and, in turn, influence the level of job burnout59. Therefore, when developing intervention measures, nursing managers should take into account the influence of different demographic characteristics on job burnout and provide targeted support strategies for high-risk groups, such as optimizing shift systems, offering career development opportunities, and increasing compensation, in order to reduce the level of job burnout among nurses.

The direct effect of intolerance of uncertainty on job burnout

The results of this study indicate that intolerance of uncertainty has a significant positive predictive effect on nurses’ job burnout (β = 0.439, P < 0.01), meaning that nurses with higher intolerance of uncertainty are more likely to experience job burnout. This finding is consistent with the results of Kuhn et al.60. This direct effect can be understood from three aspects: cognition, emotion, and behavior. Cognitively, nurses with low tolerance for uncertainty tend to view unfamiliar situations as threats, leading to negative expectations and increased psychological stress27,60. Emotionally, they are more likely to feel emotionally exhausted due to anxiety and helplessness, making it difficult to adapt to the work environment28,60. Behaviorally, these nurses may adopt avoidance strategies, such as reducing interactions with patients, lowering their work engagement, or even developing intentions to leave their job60.

This study further found that intolerance of uncertainty is most strongly associated with the emotional exhaustion dimension of job burnout. Nursing is inherently an emotionally demanding profession, where nurses must cope with emergencies and provide emotional support6. Nurses with low tolerance for uncertainty, due to their fear of the unknown, are more likely to remain in a constant state of high stress and anxiety, leading to a rapid depletion of emotional resources60. Additionally, they may experience repeated anxiety due to concerns about making mistakes in decision-making, further increasing their psychological burden and exacerbating emotional exhaustion60. Since emotional exhaustion is the core characteristic of job burnout48 and is most directly influenced by work stress, it is most closely related to intolerance of uncertainty.

The mediating role of resilience

The Job Demands-Resources Model (JD-R) posits that the degree of job burnout experienced by individuals is influenced by the dynamic balance between job demands and job resources61. When job demands are high and there is insufficient support from resources, individuals are more likely to experience emotional exhaustion and burnout. However, if individuals possess adequate job resources, such as resilience as a personal resource, they are better able to buffer the stress caused by job demands, thereby reducing the likelihood of job burnout61. In the nursing population, high work pressure and an uncertain healthcare environment constitute typical job demands24. Resilience, as a key personal resource, helps individuals positively adapt when faced with stress and uncertainty, enhancing coping abilities, reducing negative emotional experiences, and maintaining higher levels of work engagement, thus lowering the risk of burnout61. The JD-R model views resilience as a moderator, meaning that it can influence the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout. According to this model, nurses facing high levels of uncertainty, if they possess high resilience, can better regulate their emotions, adopt positive coping strategies, and mitigate the negative impact of uncertainty on job burnout. However, if resilience is low, the negative effects of uncertainty are more likely to directly translate into job burnout61. The JD-R model emphasizes resilience as a personal resource that moderates the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout. However, in addition to its moderating role, resilience may also play a deeper role in the management of personal resources. Based on the Conservation of Resources Theory (COR), resilience not only affects how individuals cope with uncertainty but may also mediate the relationship between resource depletion and job burnout.

This study found that resilience plays an important mediating role between intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout, a result consistent with the COR Theory. COR theory emphasizes that individuals, when faced with stress, strive to acquire, maintain, and protect their resources to reduce the negative impact of resource depletion26. In this study, resilience is not only a resource available to individuals but also serves as a bridge between resource acquisition and depletion. Nurses with high intolerance of uncertainty tend to have lower resilience, and the decline in resilience further exacerbates job burnout. This finding supports the view within the COR theory framework that resilience plays a critical mediating role in an individual’s resource management process. Specifically, higher tolerance of uncertainty helps individuals maintain higher levels of resilience, thereby reducing job burnout.

In summary, both the JD-R model and COR theory highlight the important role of resilience in job burnout, but their emphases differ. The JD-R model emphasizes the moderating role of resilience, focusing on whether individuals can leverage existing resources to buffer the stress brought on by job demands61. On the other hand, COR theory emphasizes the mediating role of resilience26explaining how changes in resilience affect the level of job burnout. The findings of this study support COR theory, as resilience mediates the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout. This result indirectly supports the JD-R model’s perspective on the importance of personal resources. Future research could further explore the dual role of resilience, both as a mediator and as a moderator in specific contexts, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of its mechanisms in job burnout.

The mediating role of change fatigue

The results of this study indicate that change fatigue partially mediates the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and nurse job burnout. Specifically, the stronger the tolerance for uncertainty, the lower the level of change fatigue and job burnout. In the nursing environment, the rapid development of the healthcare system, changes in hospital management models, the introduction of new technologies, and the continuous updating of nursing standards require nurses to constantly adapt to new job demands62. For nurses with low tolerance for uncertainty, frequent changes are perceived as a threat63leading to higher levels of anxiety and helplessness, making them more prone to emotional exhaustion and job burnout. Furthermore, the negative effects of change fatigue are not limited to the psychological aspect; it may also reduce nurses’ work enthusiasm, weaken their professional identity, and ultimately exacerbate job burnout64.

From the perspective of the COR theory, it posits that individuals cope with stress by protecting and accumulating resources26. When facing change, individuals need to invest substantial cognitive, emotional, and time resources to adapt to new environments. Nurses with low tolerance for uncertainty, due to their lack of psychological resources to adapt to change, are more likely to experience resource depletion, thereby increasing the risk of change fatigue and job burnout. In this study, change fatigue can be seen as a reflection of the resource consumption experienced by nurses when dealing with organizational changes. For nurses with high intolerance of uncertainty, change often means greater environmental complexity and increased stress64. Due to insufficient psychological resources to cope with these challenges, they are likely to exhibit higher levels of change fatigue. This not only leads to greater psychological pressure but may also reduce job satisfaction, further triggering job burnout64. Therefore, change fatigue is not only an individual’s negative psychological response to change but also an important mediating mechanism in the development of job burnout.

The chain mediating effect of resilience and change fatigue

Furthermore, this study is the first to analyze the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout from another perspective. We found that the chain mediation of resilience → change fatigue is also an important pathway through which intolerance of uncertainty affects job burnout. Specifically, the influence of intolerance of uncertainty on job burnout is partially mediated by its impact on resilience, which then affects the development of change fatigue. Uncertainty is an unavoidable characteristic in daily work and life27. Nurses with a high intolerance of uncertainty tend to view constantly changing patient conditions, technological updates, and management adjustments as threats63which leads to anxiety and negative expectations, depleting psychological resources and resulting in lower resilience. Nurses with lower resilience, when facing frequent organizational changes, find it difficult to adapt to the new environment through cognitive restructuring or other methods, which makes them more susceptible to additional psychological burdens and feelings of helplessness, thereby triggering change fatigue65. Change fatigue further leads to job burnout, primarily in three aspects: first, emotional exhaustion from prolonged change-related stress, which diminishes work enthusiasm66,67; second, depersonalization, causing them to lose empathy for patients and colleagues68; and finally, a decline in professional achievement, leading to self-doubt and ultimately, job burnout69.

Thus, it is evident that resilience and change fatigue play a crucial chain-mediating role between intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout among nurses. Therefore, when developing intervention strategies, nursing managers should focus on enhancing resilience and reducing change fatigue to lower the level of job burnout among nurses. First, improving nurses’ resilience can effectively buffer the negative impact of uncertainty. Managers can take the following measures to enhance resilience: (1) Provide psychological support and counseling, such as regular stress management and coping strategy training, to help nurses master techniques like cognitive restructuring and mindfulness training, enhancing their adaptability; (2) Establish a strong work support system by optimizing team collaboration and promoting mutual support among colleagues, strengthening nurses’ psychological resilience when facing challenges; (3) Encourage nurses to engage in career development planning, increasing their professional identity and reducing the burnout risk caused by career confusion. Second, reducing change fatigue helps mitigate the amplifying effect of uncertainty on job burnout. Therefore, managers should take steps to alleviate nurses’ change fatigue, including: (1) Increasing communication transparency when implementing workflow or organizational changes, ensuring nurses understand the purpose and long-term benefits of the changes to reduce anxiety caused by information asymmetry; (2) Adopting a gradual change strategy to avoid adaptation difficulties caused by multiple reforms within a short period; (3) Providing ample training resources to help nurses quickly acquire new skills, improving their ability to adapt to changes; (4) Establishing a feedback mechanism for nurses, allowing them to express their opinions during the change process, enhancing the acceptability of the changes and reducing resistance. In conclusion, the findings of this study highlight the importance of resilience and change fatigue in managing job burnout. Nursing managers can specifically reduce job burnout levels by fostering nurses’ resilience and optimizing change management strategies, thus improving nursing quality and nurses’ job satisfaction.

Limitations

This study has certain limitations. First, it employed only a cross-sectional survey method, lacking longitudinal observation of the measured indicators. Future interventional studies could be conducted to validate the findings of this research. Second, this study used a convenience sampling method and only surveyed nurses from Jinzhou City in Liaoning Province, China, which may limit the representativeness of the sample. Future research could employ random sampling and multi-center studies to enhance the representativeness and external validity of the sample. Third, data were collected solely through self-reporting, which introduces a degree of subjectivity and may lead to common method bias. Future studies could use multiple data collection methods to more accurately measure these variables.

Conclusions

To explore the mechanisms through which intolerance of uncertainty impacts nurse job burnout, this study constructed a chained mediation model. The findings indicate that resilience and change fatigue mediate the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and nurse job burnout. Therefore, we recommend that nursing managers implement interventions targeting both resilience and change fatigue to more effectively reduce job burnout among nurses.

Data availability

Data from this study can be shared with other researchers and are available from the corresponding author if the request is reasonable.

Abbreviations

- SEM:

-

Structural Equation Modeling

- IUS-12:

-

Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12

- CF:

-

Change Fatigue Scale

- S-CVI:

-

Scale Content Validity Index

- CD-RISC:

-

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale

- CMBI:

-

Chinese Maslach Burnout Inventory

- χ²/df:

-

Chi-square-test/degree of freedom

- CFI:

-

Comparative Fit Index

- IFI:

-

Incremental Fit Index

- GFI:

-

Goodness-of-Fit Index

- TLI:

-

Tucker-Lewis Index

- AGFI:

-

Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index

- SRMR:

-

Standardized Root-mean-square Residual

- RMSEA:

-

Root-mean-square Error of Approximation

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- JD-R:

-

Job Demands-Resources Model

- COR:

-

Conservation of Resources Theory

References

Ooms, A. et al. Enhancing the well-being of front-line healthcare professionals in high pressure clinical environments: A mixed-methods evaluative research project. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 132, 104257 (2022).

Ding, J., Yu, Y., Kong, J., Chen, Q. & McAleer, P. Psychometric evaluation of the student nurse stressor-14 scale for undergraduate nursing interns. BMC Nurs. 22, 468 (2023).

Lin, P. C. et al. The association between rotating shift work and increased occupational stress in nurses. J. Occup. Health. 57, 307–315 (2015).

Vogel, M., Braungardt, T., Meyer, W. & Schneider, W. The effects of shift work on physical and mental health. J. Neural Transm. 119, 1121–1132 (2012).

Zhang, X. & Zhang, L. Risk prediction of sleep disturbance in clinical nurses: a nomogram and artificial neural network model. BMC Nurs. 22, 289 (2023).

Sherman, D. W. & Nurses’ Stress & burnout: how to care for yourself when caring for patients and their families experiencing life-threatening illness. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 104, 48–56 (2004).

Farokhzadian, J., Mangolian Shahrbabaki, P., Farahmandnia, H. & Taskiran Eskici, G. Soltani goki, F. Nurses’ challenges for disaster response: a qualitative study. BMC Emerg. Med. 24, 1 (2024).

la Cañadas-De, G. A. et al. Risk factors and prevalence of burnout syndrome in the nursing profession. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 52, 240–249 (2015).

Zhang, W. et al. Burnout in nurses working in china: A National questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 27, e12908 (2021).

Zhou, L. L. et al. Demographic factors and job characteristics associated with burnout in Chinese female nurses during controlled COVID-19 period: a cross-sectional study. Front. Public. Health. 9, 757113 (2022).

Honkonen, T. et al. The association between burnout and physical illness in the general population—results from the Finnish health 2000 study. J. Psychosom. Res. 61, 59–66 (2006).

Meerlo, P., Sgoifo, A. & Suchecki, D. Restricted and disrupted sleep: effects on autonomic function, neuroendocrine stress systems and stress responsivity. Sleep. Med. Rev. 12, 197–210 (2008).

Han, K. S., Kim, L. & Shim, I. Stress and sleep disorder. Exp. Neurobiol. 21, 141 (2012).

Nash, J. M. & Thebarge, R. W. Understanding psychological stress, its biological processes, and impact on primary headache. Headache: J. Head Face Pain. 46, 1377–1386 (2006).

Kuckuck, S. et al. Glucocorticoids, stress and eating: the mediating role of appetite-regulating hormones. Obes. Rev. 24, e13539 (2023).

McEwen, B. S. Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 583, 174–185 (2008).

Vignapiano, A. & Nolfe, G. Occupational burnout syndrome among Italian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A real-world study. Eu Psychiat. 64, S104–S104 (2021).

Linden, D. V. D., Keijsers, G. P., Eling, P. & Schaijk, R. V. Work stress and attentional difficulties: an initial study on burnout and cognitive failures. Work Stress. 19, 23–36 (2005).

Kakiashvili, T., Leszek, J. & Rutkowski, K. The medical perspective on burnout. Int. J. Occup. Med. Env. 26, 401–412 (2013).

Agyapong, B., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Burback, L. & Wei, Y. Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among teachers: A scoping review. Int. J. Env Res. Pub He. 19, 10706 (2022).

Andela, M. Work-related stressors and suicidal ideation: the mediating role of burnout. J. Workplace Beheav He. 36, 125–145 (2021).

Leitão, J., Pereira, D. & Gonçalves, Â. Quality of work life and contribution to productivity: assessing the moderator effects of burnout syndrome. Int. J. Env Res. Pub He. 18, 2425 (2021).

Ren, Z. et al. Relationships of organisational justice, psychological capital and professional identity with job burnout among Chinese nurses: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 30, 2912–2923 (2021).

Fennell, M. L. & Adams, C. M. US health-care organizations: complexity, turbulence, and multilevel change. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 37, 205–219 (2011).

Malouf, P., Quinlan, E. & Mohi, S. Predicting burnout in Australian mental health professionals: uncertainty tolerance, impostorism and psychological inflexibility. Clin. Psychol. 27, 186–195 (2023).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513 (1989).

Hillen, M. A., Gutheil, C. M., Strout, T. D., Smets, E. M. & Han, P. K. Tolerance of uncertainty: conceptual analysis, integrative model, and implications for healthcare. Soc. Sci. Med. 180, 62–75 (2017).

Chen, C. Y. & Hong, R. Y. Intolerance of uncertainty moderates the relation between negative life events and anxiety. Pers. Indiv Differ. 49, 49–53 (2010).

Di Trani, M., Mariani, R., Ferri, R., De Berardinis, D. & Frigo, M. G. From resilience to burnout in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 emergency: the role of the ability to tolerate uncertainty. Front. Psychol. 12, 646435 (2021).

Ong, A. D., Bergeman, C. S., Bisconti, T. L. & Wallace, K. A. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91, 730 (2006).

Tian, Y. & Wang, Y. L. Resilience provides mediating effect of resilience between fear of progression and sleep quality in patients with hematological malignancies. World J. Psychiatr. 14, 541 (2024).

Dugas, M. J., Schwartz, A. & Francis, K. Brief report: intolerance of uncertainty, worry, and depression. Cogn. Ther. Res. 28, 835–842 (2004).

Cleary, M., Kornhaber, R., Thapa, D. K., West, S. & Visentin, D. The effectiveness of interventions to improve resilience among health professionals: A systematic review. Nur Educ. Today. 71, 247–263 (2018).

McMillan, K. & Perron, A. Nurses Amidst Change: The Concept of Change Fatigue Offers an Alternative Perspective on Organizational Change. Pol Polit Nurs. Pract, (2013).

Koy, V., Yunibhand, J., Angsuroch, Y. & Fisher, M. L. Relationship between nursing care quality, nurse staffing, nurse job satisfaction, nurse practice environment, and burnout: literature review. J. Res. Med. Sci. 3, 1825–1831 (2015).

Tiittanen, H., Heikkilä, J. & Baigozhina, Z. Development of management structures for future nursing services in the Republic of Kazakhstan requires change of organizational culture. J. Nurs. Manage. 29, 2565–2572 (2021).

Zohar, D. & Luria, G. A multilevel model of safety climate: cross-level relationships between organization and group-level climates. J. Appl. Psychol. 90, 616 (2005).

Bakker, A. B. & Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: state of the Art. J. Manage. Psychol. 22, 309–328 (2007).

Huynh, C. et al. Change implementation: the association of adaptive reserve and burnout among inpatient medicine physicians and nurses. J. Interprof Care. 32, 549–555 (2018).

Lotfi, Y. et al. Investigating the consequences of change fatigue in health care workers. J. Occup. Hyg. Eng. 10, 240–250 (2024).

Podsakoff, P. M. & Organ, D. W. Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J. Manage. 12, 531–544 (1986).

Kline, R. B. & Santor, D. A. Principles & practice of structural equation modelling. Can. Psycho. 40, 381 (1999).

Wu, L. J., Wang, J. N. & Qi, X. D. Validity and reliability of the intolerance of uncertainty Scale-12 in middle school students. Chin. Ment Health J. 9, 700–705 (2016).

Yu, X. & Zhang, J. Factor analysis and psychometric evaluation of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC) with Chinese people. Soc. Behav. Personal. 35, 19–30 (2007).

Li, Y. X. & Wu, M. Z. A structural study of job burnout. Psychol. Sci. 28, 454–457 (2005).

Zhang, S. et al. A cross-sectional study of job burnout, psychological attachment, and the career calling of Chinese Doctors. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20, 1–11 (2020).

Fang, J. & Zhang, M. Q. Assessing point and interval Estimation for the mediating effect: distribution of the product, nonparametric bootstrap and Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. Acta Psychol. Sin (2012).

Cordes, C. L. & Dougherty, T. W. A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Acad. Manage. Rev. 18, 621–656 (1993).

Qu, G. et al. Study on current situation and Spatial distribution of job burnout of nurses in emergency department in China. Chin. J. Health Policy. 15, 71–76 (2022).

Wang, Q. Q., Lv, W. J., Qian, R. L. & Zhang, Y. H. Job burnout and quality of working life among Chinese nurses: A cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Manage. 27, 1835–1844 (2019).

Johnson, M., Cowin, L. S., Wilson, I. & Young, H. Professional identity and nursing: contemporary theoretical developments and future research challenges. Int. Nurs. Rev. 59, 562–569 (2012).

Kirpal, S. Work identities of nurses: between caring and efficiency demands. Career Dev. Int. 9, 274–304 (2004).

Zhang, H. et al. Growth and challenges of china’s nursing workforce from 1998 to 2018: A retrospective data analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 124, 104084 (2021).

Ma, Z., Li, C. & Zhang, J. Understanding urban shrinkage from a regional perspective: case study of Northeast China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 146, 05020025 (2020).

Van de Vliert, E., Yang, H., Wang, Y. & Ren, X. Climato-economic imprints on Chinese collectivism. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 44, 589–605 (2013).

Ke, Y. T. & Stocker, J. F. On the difficulty of finding one’s place: A qualitative study of new nurses’ processes of growth in the workplace. J. Clin. Nurs. 28, 4321–4331 (2019).

Han, P., Duan, X., Wang, L., Zhu, X. & Jiang, J. Stress and coping experience in nurse residency programs for new graduate nurses: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Front. Public. Health. 10, 979626 (2022).

Li, Y. F., Chao, M. & Shih, C. T. Nurses’ intention to resign and avoidance of emergency department violence: A moderated mediation model. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 39, 55–61 (2018).

Ma, C. C., Samuels, M. E. & Alexander, J. W. Factors that influence nurses’ job satisfaction. J. Nurs. Admin. 33, 293–299 (2003).

Kuhn, G., Goldberg, R. & Compton, S. Tolerance for uncertainty, burnout, and satisfaction with the career of emergency medicine. Ann. Emerg. Med. 54, 106–113 (2009). e106.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F. & Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 499 (2001).

McMillan, K. A Critical Organizational Analysis of Frontline Nurses’ Experience of Rapid and Continuous Change in an Acute Health Care Organization (Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa, 2018).

Garrison, Y. L., Lee, K. H. & Ali, S. R. Career identity and life satisfaction: the mediating role of tolerance for uncertainty and positive/negative affect. J. Career Dev. 44, 516–529 (2017).

Brown, R., Wey, H. & Foland, K. The relationship among change fatigue, resilience, and job satisfaction of hospital staff nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 50, 306–313 (2018).

Xu, X., Yan, X., Zhang, Q., Xu, C. & Li, M. The chain mediating role of psychological resilience and neuroticism between intolerance of uncertainty and perceived stress among medical university students in Southwest China. BMC Psychiatry. 23, 861 (2023).

Stordeur, S., D’hoore, W. & Vandenberghe, C. Leadership, organizational stress, and emotional exhaustion among hospital nursing staff. J. Adv. Nurs. 35, 533–542 (2001).

Giæver, F. & Smollan, R. K. Evolving emotional experiences following organizational change: a longitudinal qualitative study. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. 10, 105–133 (2015).

Delgado, N., Delgado, J., Betancort, M., Bonache, H. & Harris, L. T. What is the link between different components of empathy and burnout in healthcare professionals? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Res. Behav. Ma, 447–463 (2023).

Kalliath, T. & Morris, R. Job satisfaction among nurses: a predictor of burnout levels. J. Nurs. Admin. 32, 648–654 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the hospital staff and all participants for their active cooperation.

Funding

This study was supported by the Liaoning Province Social Science Planning Fund (No. L21BED006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YQG: research design, collected data, analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. HJR: data cleaning and interpretation of the data. GM: Interpretation of the data and language embellishment. XDY: collected data and analyzed data. PJ and YC: data entry and reconciliation. GW: research design, collected data, and gave technical and writing instructions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Y., Ren, H., Meng, G. et al. The chain mediating role of resilience and change fatigue between intolerance of uncertainty and job burnout in nurses. Sci Rep 15, 22469 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06803-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06803-2