Abstract

Transition metal chalcogenides are promising compounds in electrochemistry with different applications including energy conversion/storage devices due to their stability, different oxidation states, and highly active surface areas. In this work, ZnCoTe nanorods coated with NiCoSe2 as the shell have been synthesized by a two-step method. ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 has an excellent specific capacity of 240 mAh g−1 at a current density of 2 A g−1 in a three-electrode system containing 3 M KOH electrolyte solution, which is much superior to each of the core and shell components of the constructed electrodes. Furthermore, a remarkable cycle life of 94% is obtained at a current density of 10 A g−1 after 5000 cycles, suggesting its long-term stability. The hybrid supercapacitor consists of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 and activated carbon as the positive and negative electrodes, respectively. In addition, ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2//AC (HSC device) showed 580 W kg−1 power density at an energy density of 57 Wh kg−1. Additionally, the device retained 90% of its initial capacitance after 5000 cycles. Eventually, considering the excellent electrical conductivities and large numbers of active sites, transition metal chalcogenides have been utilized as efficient electrodes for supercapacitor applications. This work introduces a method for the incorporation of zinc into the telluride matrix, which modulates the electronic structure, enhances intrinsic electrical conductivity, and increases the density of electroactive sites. Moreover, the engineered core–shell architecture of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe₂ provides a synergistic combination of high electrical conductivity, abundant active sites, and a well-organized hierarchical structure. These integrated features significantly boost charge storage performance and overall efficiency of the supercapacitor device.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The demand for cost-effective and eco-friendly electrical energy storage devices has led to the necessity of energy storage systems in modern societies1. Clean energy storage devices, including batteries, supercapacitors (SCs), and fuel cells are considered alternatives to fossil fuels1,2. SCs are a class of promising energy storage systems with excellent advantages such as high-rate capability, long cycle life, good reversibility, fast charge-discharge rate, low cost, and high power density3. These devices are divided into two groups; namely, electric double-layer capacitors (EDLC) and pseudo capacitors (PCs)4. To enhance the energy densities, the application of hybrid supercapacitors (HSCs) has become one of the most promising approaches by combining the excellent energy density of battery-type faradaic electrodes with a carbon-negative electrode4,5. The energy storage performance of HSCs primarily depends on the properties of electrode materials. However, their practical applications have been limited due to low electric conductivity and slow ion diffusion. To overcome these constraints, bimetallic oxides and sulfides have been developed. Meanwhile, the synergistic effect between different metal ions such as multiple redox active sites, high specific energy, and power density can efficiently enhance their performance6,7,8,9,10.

Among diverse electrode materials, transition metal chalcogenides (TMC) have attracted remarkable attention as a new type of electroactive material in the field of energy storage and conversion systems owing to their valuable electrochemical characteristics such as multiple valence states, rich redox chemistry, fast ion diffusion kinetics, morphological diversity, and higher electronic conductivity compared to their oxide and sulfide counterparts11,12,13. However, the disadvantages of TMCs are poor rate performance, capability, and surface area. Mixed metal chalcogenides such as selenide and telluride, which are a new type of positive electrode active materials with remarkable electrochemical performance, provide prominent various oxidation states, well-defined morphology, and intrinsic electroactive sites for electrochemical processes13,14,15,16,17. Although transition metal chalcogenides (TMCs) such as tellurides and selenides have shown great promise as electrode materials for hybrid supercapacitors (HSCs) due to their rich redox chemistry and high conductivity, challenges remain in achieving high-capacity retention under long-term cycling, and in improving ion diffusion at higher current densities. Specifically, many TMC-based electrodes suffer from structural instability and sluggish ion transport, especially when synthesized without hierarchical or engineered morphologies13,14,15,16,17,18,19. In addition, while core–shell architectures have emerged as a strategy to enhance electrochemical performance by integrating complementary properties of two materials, the combination of ZnCoTe as a core and NiCoSe₂ as a shell remains underexplored15,16,17,18,19.

TMCs have shown considerable potential in SCs as battery-type electrode active materials. Furthermore, different types of TMCs have been reported as cathodic materials for the fabrication of HSC due to their good performance and structure13,18,19. For instance, NiFe-MOF@NiFeTe nanorods with a specific capacitance of 1245 F g−1 at 5 A g−1 and 92% retention after 10,000 cycles were prepared by a simple two-step hydrothermal method. The combination of MOF and metal telluride demonstrated good electrochemical performance. Moreover, the as-prepared NiFe-MOF@NiFeTe//AC HSC showed good energy and power densities20. Liu et al.21 successfully prepared a NiSe/NiTe2 nanocomposite by microwave method on nickel foam (NF). The prepared electrode delivered a specific capacitance of 1782.7 F g−1 at a current density of 1 A g−1. In addition, NiSe/NiTe2//AC solid-state asymmetric supercapacitor showed an energy density of 23.26 Wh kg−1. NiLaTe microfibers22 were fabricated on NF based on a wet chemical technique to investigate the Ni, La, and Te ions in the one-dimensional NiLaTe MF structure. The as-fabricated electrode showed a specific capacity of 215 mAh g−1 at a current density of 1 A g−1. NiTe-decorated ZIF-67 has been prepared by hydrothermal approach23. NiTe@Zif67 displayed a specific capacitance of 1521 F g−1 at a current density of 1 A g−1. The fabricated NiTe@Zif67//AC asymmetric supercapacitor showed a high energy density of 45.3 Wh kg−1 at a power density of 5689.1 W kg−1.

In the present work, ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 with a nanorod morphology as a positive electrode active material in the fabricated HSC has been synthesized by hierarchical hydrothermal and electrodeposition methods. Moreover, a core-shell structure with a high surface area can efficiently accelerate the ion diffusion of electrolyte ions. In comparison to ZnCoTe and NiCoSe2 electrodes, ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 demonstrated better electrochemical performance. The core-shell structure showed good electrochemical performance with a high specific capacity of 240 mAh g−1 at a current density of 2 A g−1 and cycling stability of 94% after 5000 cycles. Moreover, HSC ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2//AC was constructed and showed outstanding performance. HSC had a high energy density of 57 Wh kg−1 at a power density of 580 W kg−1 and 90% stability after 5000 cycles. Additionally, telluride with a larger atomic size, higher electronic conductivity, and lower electronegativity improved diffusion kinetics and electrochemical performance.

Experimental section

Chemicals

All chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification. Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)3.6H2O), cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)3.6H2O), urea (CH4N2O), sodium tellurite (Na2TeO3), hydrazine hydrate (N2H4·H2O), nickel chloride hexahydrate (NiCl2.6H2O), cobalt chloride hexahydrate (CoCl2.6H2O), selenium dioxide (SeO2), lithium chloride (LiCl), potassium hydroxide (KOH), acetone, ethanol, carbon black, active carbon (AC), polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF), and N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) were purchased from Merck and Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co.

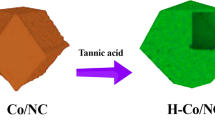

Synthesis of Nanorod ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2

Figure 1. represents the synthesis of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 nanorods. ZnCoTe nanorods were synthesized by a facile hydrothermal process on NF and subsequent ion exchange reactions. First, Zn(NO3)3.6H2O, Co(NO3)3.6H2O, and CH4N2O (urea) with a molar ratio of 1: 1: 4 were dissolved in 40 mL of water, followed by the addition of a piece of NF. The solution was then kept in a Teflon lined stainless-steel autoclave for 8 h at a temperature of 150 °C. Next, ZnCoLDH was rinsed with deionized water and dried at 60 °C for 12 h. In the next step, ZnCoLDH on NF was immersed into a 40 mL solution containing Na2TeO3 (200 mg) and hydrazine hydrate (5 mL) and maintained in a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave at 180 °C for 12 h. Na2TeO3 solution was used as the anionic precursor whereas the addition of hydrazine resulted in the formation of TeO32− species, which react with N2H4 and finally form Te2−. Next, the as-prepared electrode was rinsed with deionized water and dried at 60 °C. An ion exchange process was carried out to convert ZnCoLDH to ZnCoTe. To further study the performance of ZnCoTe electrode, it was synthesized using different ratios of Zn: Co (2:1, 1:1, 1:2)24,25.

In the next step, NiCoSe2 was coated as the shell on ZnCoTe nanorods. The deposition electrolyte consisted of 10 mM CoCl2·6H2O, 10 mM NiCl2·6H2O, 20 mM SeO2, and 300 mg of LiCl in deionized water26,27. Electrodeposition was carried out in a three-electrode system containing Pt wire, Ag/AgCl, and ZnCoTe as the counter, reference, and working electrodes, respectively, by cyclic voltammetry (CV) method in the potential range of −1.6–0 V, using 5 cycles at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1. Finally, the as-prepared electrode was washed with deionized water and dried at 60 °C for 12 h. The mass loading of the material on NF was about 1.7 mg. The mass loading of the active material typically plays a critical role in the electrochemical performance of supercapacitors. At low mass loadings, ions can easily access the electroactive sites, resulting in higher specific capacitance or capacity values due to the efficient utilization of the active material.

Electrochemical measurements

The electrochemical behavior of the electrodes in three-electrode and two-electrode systems were studied by CV, galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) using a standard three-electrode system with 3 M KOH as the electrolyte by a µ-Autolab TYPE III electrochemical instrument (Eco Chemie B. V., Ultrecht, The Netherlands). The test voltage windows of CV and GCD in three-electrode systems were − 0.2–0.7 V and 0–0.5 V, respectively. Furthermore, the measurement range of EIS was from 0.01 Hz to 1000 kHz.

The specific capacity (mAh g−1) of the as-prepared positive electrodes was calculated from the GCD curve based on the following Eqs28,29.:

Preparation of asymmetric device

In 3 M KOH, the as-prepared ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 and AC electrodes were used as the positive and negative electrodes, respectively. The negative electrode was fabricated by mixing carbon black (10%), PVDF (10%), and AC (80%). Next, a sufficient amount of NMP solvent was added to the above mixture, which was then dried at 60 °C overnight.

The specific capacitance (Cs, F g−1) in the hybrid supercapacitor was determined using Eq. (2)30,31:

where I, t, M, and V show the response current density (A g−1), discharge time (s), total mass of the active material (g), and potential window (V), respectively.

The mass ratio of the ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 and AC was obtained based on the charge balance relationship (q+ = q −). Mass balancing was calculated using Eq. 432:

The energy and power densities of the hybrid supercapacitor were calculated by the following equations, respectively30,32:

where E (Wh kg−1), P (W kg−1), Cs (F g−1), ∆V (V), and ∆t (s) are the energy density, power density, specific capacitance of the device, the potential window, and discharge time, respectively.

Structural characterizations

The morphology and structure of the as-fabricated electrodes were investigated by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM, MIRA3 TESCAN, 15 kV, Czech) equipped with Energy-dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM, 200 kV Schottky instrument.). An X-ray diffraction system (XRD, Rigaku) was used to determine the crystalline phase of the electrode materials. N2 adsorption-desorption tests were performed to determine the surface area and the pore size distribution of samples (BET, Bel, Belsorp mini, Japan). The elemental composition and the various oxidation states were obtained by X-ray Photoelectron Microscopy (XPS, SPECS UHV analysis).

Results and discussion

Physiochemical characterization of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2

The surface morphological architecture of the ZnCoTe and ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 electrodes was studied by SEM technique. The surface morphology of pure ZnCoTe is depicted in Fig. 2. Figure 2a shows the SEM image of the ZnCoTe nanorod at 500 nm magnifications. ZnCoTe with nanorod-like architecture is grown on the NF as the substrate. According to Figs. 2b-c, ZnCoTe nanorod is a network structure with a 3D porous architecture, which can provide high electroactive surface area. According to Fig. 2d, the EDS spectrum of ZnCoTe confirms the presence of Zn, Co, and Te in the sample. Additionally, elemental mapping was used to determine the distribution of Zn, Co, and Te in the as-prepared electrode. Figure 2e confirms the uniform growth of each of the elements on the NF.

The SEM images in Fig. 4. show the uniform coting of ZnCoTe nanorods with NiCoSe2. After the electrodeposition of nanoparticles of NiCoSe2 (Fig. 4a), the surface of ZnCoTe rods becomes rougher, resulting in the co-existence of ZnCoTe nanorods and NiCoSe2 nanoparticles. In addition, the SEM images (Figs. 4b-c) indicate that the surface of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 nanorod becomes relatively rougher than that of ZnCoTe precursors. Such a structure provides numerous paths for the penetration of electrolyte ions and increases the microscopic surface area for OH–. Moreover, the elemental composition of ZiCoTe@NiCoSe2 investigated by EDS (Fig. 4 d) confirms the presence of Zn, Co, Ni, Te, and Se elements. As shown in Fig. 4e, the elemental mapping reveals a homogenous distribution of Zn, Ni, Co, Te, and Se elements, indicating the successful fabrication of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2.

Figure 4. shows the TEM image of ZnCoTe and ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 nanorods as a core-shell structure. Figure 4a shows that the synthesized ZnCoTe nanorod has a uniform and smooth surface. The TEM image of the core-shell structure of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 is shown in Figs. 4b-c. ZnCoTe nanorods have been well covered by NiCoSe2 without change in the morphology of the nanorods. The TEM images display reasonable agreement with the results of the SEM images.

The crystal structures of ZnCoTe and ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 electrodes were investigated using XRD technique and the results are shown in Fig. 5. Clearly, three sharp peaks can be observed for both electrodes at 2θ values of 44.5, 51.8, and 76.4°, arising from NF substrate. According to JCPDS No. 00-004-0850, these peaks are assigned to the crystal planes of (111), (200), and (220), respectively, for the nickel cubic crystal system. The peaks at 2θ values of 30.9, 42.7, and 45.8° are related to the monoclinic crystal structure of the nickel tellurate for the crystal planes of (402), (511), and (223), respectively (JPCDS No. 00-025-0586). The two peaks located at 2θ values of 29.9 and 57.9° can be assigned to (200) and (240) crystal planes corresponding to the orthorhombic crystal system of cobalt tellurite, according to JCPDS No. 00-029-0510. A closer view at the peaks at 2θ values of 51.8 and 76.4° shows that these peaks are overlaps of the signals arising from (200) and (116) planes of hexagonal zinc telluride, respectively, (JCPDS No. 01-083-0966) with the related planes of nickel crystal. All the above-mentioned peaks are observed in both electrodes, which confirms the presence of a solid solution phase of Zn, Co, Ni, and Te elements. Two additional weak peaks at 2θ values of 36.4 and 75.2°, which were observed only in the ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 electrode, can be assigned to the planes of (002) and (402), respectively, for the orthorhombic nickel selenate system (JCPDS No. 00-031-0913). Therefore, the presence of Se in the solid solution phase Ni, Zn, Co, and Te is verified for this electrode.

The surface chemical composition of the layer was evaluated by XPS analysis. Figure 6a shows a survey XPS spectrum of the electrode materials. The clear signals due to Ni, Co, Se, O, and C elements can be observed in this spectrum. Environmentally adsorbed carbon species such as CO and CO2 are responsible for such intense O 1 s and C 1 s signals. There are no signals related to Zn and Te elements, indicating that the NiCoSe2 shell has completely covered the ZnCoTe core. Therefore, no signal can be observed corresponding to covered Zn and Te elements. Figure 6b presents the high-resolution XPS spectrum of the Se 3 d core level. Spin-orbit splitting of Se 3 d orbital deconvolutes this signal into two main peaks located at binding energies (BE) of 59.2 and 60.1 eV. These peaks, which have an energy difference of ~ 0.9 eV, are specific signals generated by 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 energy levels33,34,35. A high-resolution Ni 2p core-level spectrum has been shown in Fig. 6c. This signal has been deconvoluted into two main peaks located at BE values of 855.9 and 873.9 eV with a separation of 18 eV, related to the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 spin-orbit splitting of Ni 2p orbital, respectively36,37. These two peaks are accompanied by corresponding satellite peaks with BE values of 862.1 and 880.2 eV, respectively. The observed properties of the Ni 2p signal indicate the presence of a Ni2+ oxidation state. Figure 6d displays the window of the Co 2p XPS signal. As can be observed, the signal is composed of two peaks with BE values of 781.4 and 797.5 eV, with an energy difference of 16.1 eV, verifying the Co2+ oxidation state38,39,40.

To further analyze the core-shell structure of the ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2, the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms were obtained (Fig. S1). In addition, the ZnCoTe covered by NiCoSe2 can offer a large SA = 65.4 m2 g−1 and a favorable porous nature, which allows ions to access the whole surface of structures, providing higher capacity. As observed in Fig. S1a, ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 shows the typical III isotherm with a hysteresis loop characteristic of mesoporous materials. Furthermore, Fig. S1b shows the pore size distributions of samples, confirming their mesoporous structure for them41,42. This roughness increases the active surface area, promotes electrolyte penetration, and shortens ion/electron diffusion pathways, which are the key parameters for improving capacitance and cycling stability. However, ZnCoTe@NiCoSe₂ heterostructure shows a markedly higher surface area. Furthermore, the total pore volume and pore size distribution have shifted toward porous ranges, which are known to facilitate efficient ion transport and buffering during charge/discharge processes.

Electrochemical performance tests

The electrochemical performance of the as-prepared electrodes was studied using a three-electrode system in 3 M KOH electrolyte. According to Fig. S2, the electrochemical behavior of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 in 3 M KOH, as the optimized value, is comparable with that of the other concentrations (1 and 6 M) and is more advantageous for improving super capacitive properties. Figure 7a displays the CV curves of ZnCoTe, NiCoSe2 and ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 at the scan rate of 50 mV s−1 and potential window of −0.2–0.7 V. As observed, the nanorod ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 hierarchical nanocomposite exhibits more redox reactions involved in the electrochemical energy storage process. Additionally, the integral area of the CV curve from nanorod ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 is much larger than those of ZnCoTe and NiCoSe2, which further shows the advantages in charge storage with more active sites and larger surface area.

It can be seen that at different scan rates, two pairs of reduction peaks are displayed. The possible electrochemical redox reactions for ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 core-shell structure in 3 M KOH electrolytes are as follows43,44;

Figure 7b shows the ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 curve at different scan rates in the range of 10–70 mV s−1. The CV curves show redox peaks, verifying the Faradic reactions in the energy storage mechanism. In addition, good reversibility is observed by increasing the scan rate. Additionally, Fig. S3 demonstrates the CV curve of ZnCoTe (Zn: Co, 1:1, 1:2, and 2:1) at different scan rates in the range of 10–70 mV s−1. Based on the obtained results, the ZnCoTe (Zn: Co, 1:1) was selected as the optimized electrode. Furthermore, the CV curve of NiCoSe2 is shown in Fig. S4 at different cycle numbers (2, 5, and 10). Moreover, NiCoSe2 with 5 cycles was determined as the electrode with the best performance.

Figure 7c illustrates the linear relationship between the peak current density and the square root of peak currents at various scan rates for the ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 electrode. The linear relationship between the redox peak current and the square root of the scan rate indicates the diffusion-controlled electrochemical process at the surface of the ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2. Moreover, for the electrochemical reaction kinetics of charge storage, the relationship between the peak current density (A g−1) and the scan rate (ν, mV s−1) was calculated using Eq. (12)42,45:

The b value was calculated from the slope of the log i vs. log v curve and varied in the range of 0.5 < b < 1.0, which indicates capacitive or diffusion-controlled processes. Herein, the values of ‘b’ for both the anodic and cathodic peaks of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 were 0.52 and 0.56, respectively, showing that the electrode process is completely diffusion controlled (battery-type electrode) (Fig. 7d). Moreover, by investigating the charge storage process of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 nanorod, the capacitive contribution of diffusion and capacitor behaviors at different scan rates were calculated based on Eq. (13)22,31:

Additionally, Fig. 7e shows the capacitive contribution at various scan rates. It can be observed that the contribution of diffusion-controlled current is 88.7% at 10 mV s−1 and decreases to 47.1% at 70 mV s−1. Figure 7f shows the contribution of the presence of 11.3% capacitance to the entire capacity at the scan rate of 10 mV s−1.

(a) CV curves of ZnCoTe, NiCoSe2, and ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 at scan rate of 50 mV s−1, (b) CV curves of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 at various scan rates, (c) Randles-Sevcik plots of ZnCoTe@NiCo2Se2 (d) The linear curve of log of peak currents as a function of the log of sweep rates, (e) Relative contribution of the capacitive and diffusion-controlled charge storage at different scan rates of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 electrode and (f) CV plots with diffusive and capacitive contrib ution at scan rate of 10 mV s−1.

GCD analysis provides the best approach to measuring the specific capacity and rate capability of the electroactive materials. A comparison of the GCD curves of ZnCoTe, NiCoSe2, and ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 at a current density of 2 A g−1 and a potential window of 0–0.5 V is shown in Fig. 8a. ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 electrode has a much larger specific capacity of 240 mA h g−1 at a current density of 2 A g−1 compared to ZnCoTe (160 mA h g−1) and NiCoSe2 (145 mA h g−1). The results of the rate capability for various electrodes are summarized in Fig. S5. The higher specific capacity of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 is attributed to its more active sites, larger surface area for Faradaic redox reactions, specific morphology, and the synergistic effect between the core and shell materials, which allows effective diffusion of electrolyte in the charge storage process. Moreover, the GCD curve of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 electrode at different current densities in the range of 2–20 A g−1 are shown in Fig. 8b. The GCD plateau of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 remains symmetrical with increasing current densities, indicating that ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 has a reversible faradic behavior and an outstanding rate performance. The specific capacities of the ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 electrode are 240, 224, 204, 192, 182, 163, and 150 mAh g−1 at current densities of 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, and 20 A g−1, respectively. The GCD curves of ZnCoTe (Zn: Co 1:1, 1:2 and 2:1) at different current densities in the range of 2–20 A g−1 are shown in Fig. S6 and the specific capacities of the as-prepared electrodes are shown in Fig. S7.

In addition, the GCD curve of NiCoSe2 at different cycle numbers (2, 5, and 10) is shown in Fig. S8 and the specific capacity vs. current density of NiCoSe2 is observed in Fig. S9. Based on Figs. S6 and S8 (the GCD curves), ZnCoTe (Zn: Co 1:1) and NiCoSe2 show better supercapacitor performances in the 5th cycle.

EIS was carried out to investigate the intrinsic electrochemical properties of the as-fabricated electrode. According to the Nyquist plots fitted equivalent circuit (Fig. 8c), the series resistance values (Rs) of ZnCoTe nanorod arrays and ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 hierarchical core-shell are about 1.45 and 1.33 Ω, respectively. The charge transfer resistance (Rct) calculated for ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 (0.431 Ω) and NiCoSe2 (0.863 Ω) from the semicircular diameter implies faster carrier diffusion for the core-shell structure. Based on the EIS assessment, smaller Rs (0.120 Ω) and Rct (0.432 Ω) values were obtained from ZnCoTe@NiCoSe compared to ZnCoTe, which can be considered strong evidence for the effect of the presence of chalcogenide on improving the electrode conductivity. EIS further confirms the improved charge transport behavior. Additionally, the Warburg region slope is steeper, suggesting enhanced ion diffusion at the electrode/electrolyte interface. Overall, the synergistic combination of structural roughness, increased porosity, and enhanced conductivity directly contribute to the superior electrochemical performance of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe₂ electrode, its high capacity, excellent rate capability, and long-term stability.

Moreover, excellent cycle life is an essential indicator of the performance of electrode materials in SC applications. Figure 8d indicates 94% capacitance retention after 5000 cycles for the electrode at a current density of 10 A g−1.

To further study the practical application of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 as the positive electrode (−0.2–0.7 V) and AC (−1–0 V) as the negative electrode, they were used to assemble a hybrid supercapacitor. Figure 9a shows the CV curves of the ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 and AC electrodes at 50 mV s−1. The HSC device shows an operating voltage as high as 1.7 V (Fig. 9a). The CV curves show the characteristics of double-layer capacitance and pseudocapacitor at different scan rates. Figure 9b shows the CV curve of the HSC device at different scan rates in the range of 10–100 mV s−1. The CV curves of the HSC device at various potential windows are illustrated in Fig. 9c. It is clear that the HSC device demonstrates reasonable performance under diverse operating voltages. The GCD curves of the fabricated HSC device at various current densities in the range of 2–20 A g−1 are shown in Fig. 9d.

According to the GCD curves (Fig. 10a) and Eq. 3, the specific capacitance of the HSC device is 140, 125, 111, 100, 95, 86, and 75 F g−1 at current densities 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, and 20 A g−1, respectively. Moreover, the HSC device maintains 90% of its initial capacitance after 5000 cycles of operation, indicating its excellent cycle stability and sufficient stability to bear the long-term cycling process (Fig. 10b). Additionally, the symmetric shape of the retention plot, which indicates drift and the low variation in potential plateaus over 5000 cycles, confirm good electrochemical stability. Furthermore, the HSC device shows a coulombic efficiency of 97.5% at the end of the cycling test, which strongly indicates the high reversibility of the charge storage process. This high coulombic efficiency suggests that the majority of the charge involved during charging is effectively recovered during discharging, with minimal parasitic or side reactions. Such performance is a key indicator of electrochemical stability and highlights the practical applicability of the HSC device for long-term energy storage (Fig. 10b).

The Ragone plot of the HSC device based on the specific energy and power values, which were acquired from the above GCD plots, is shown in Fig. 10c. Furthermore, the prepared HSC device has a high operating voltage of 1.7 V, and the most important parameters, which determine the energy storage capability of the supercapacitor electrode are an energy density of 57 W h kg−1 at a power density of 580 W kg−1. To confirm the practicability of HSC device, a green light-emitting diode (LED) can be easily lightened (Fig. 10d) by connecting two ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2//AC devices in series. The results indicate that the as-made HSC device with its facile, affordable fabrication method, has considerable potential for application as an attractive and high-quality energy storage device. Moreover, the electrochemical performance of the prepared ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 electrode in three and two electrode systems has been compared with those reported in other works in Table 1.

Conclusion

In summary, a hierarchical ZnCoTe@NiCoSe nanorod as core@chell has been successfully synthesized by a facile procedure involving the hydrothermal and electrodeposition on NF as the substrate. The unique core-shell structure allows abundant exposed electroactive sites and effectively improves the internal electronic properties of the electrode, leading to the full utilization of the whole material and facilitating rapid redox reaction kinetics. In particular, the results showed that ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 electrode had superior specific capacity 240 mAh g−1 at 2 A g−1 and durability (maintaining 93.5% after 5000 cycles at 10 A g−1).

The as-fabricated hybrid supercapacitor based on ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2//AC device had a specific capacitance of 140 F g−1 at a current density of 2 A g−1 and excellent cycling performance (86% capacity retention after 4000 cycles). Furthermore, it possessed a high energy density of 57 W h kg −1 at a power density of 580 W kg−1.

In addition, ZnCoTe@NiCoSe can be considered a promising energy storage material with high specific energy and power. Additionally, transition metal chalcogenides are promising for some energy storage devices such as batteries and fuel cells due to their versatile crystal structures, enhanced electrochemical activity, excellent redox chemistry, and enhanced electronic conductivity and are being developed for modern consumer applications. The novelty of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe₂ core-shell material is its dual transition metal telluride core (Zn and Co), which enhances electronic conductivity and redox activity, coupled with a bimetallic selenide shell providing additional active sites and surface roughness for enhanced electrochemical performance. This synergy between the unique composition and hierarchical structure distinguishes our work from prior studies. Additionally, the two-step hydrothermal–selenization synthesis method enables the controlled growth of NiCoSe₂ shell on ZnCoTe nanorods, resulting in a highly porous and rough surface morphology, which promotes efficient electrolyte penetration and rapid ion transport. This tailored interface engineering between the core and shell creates synergistic electrochemical interactions, which improve both charge storage capacity and structural integrity during long-term cycling.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Patil, J. V. et al. Electrospinning: A versatile technique for making of 1D growth of nanostructured nanofibers and its applications: an experimental approach. Appl. Surf. Sci. 423, 641–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.06.116 (2017).

Scarpa, D. et al. Self-assembled monolayers of reduced graphene oxide for robust 3D-printed supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 14, 14998. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-65635-8 (2024).

Yongmei, L., Li, J., Chen, C. & Liu, W. ZnO-MnO2 co-modified hierarchical porous carbon nanofiber film electrodes for high-energy density supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 15, 6393. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90747-0 (2025).

Pathak, M. et al. High energy density supercapacitors: an overview of efficient electrode materials, electrolytes, design, and fabrication. Chem. Rec. 24, e202300236. https://doi.org/10.1002/tcr.202300236 (2024).

Mahmoudi-Qashqay, S., Zamani-Meymian, M. R. & Maleki, A. A simple method of fabrication hybrid electrodes for supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 14, 29105. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80243-2 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Assembly of high-performance nickel–cobalt supercapacitors modified with heteroatomic polymer carbon. Appl. Surf. Sci. 648, 159067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.159067 (2024).

Nasiri, F., Fotouhi, L., Shahrokhian, S. & Zirak, M. Cobalt sulfide flower-like derived from metal organic frameworks on nickel foam as an electrode for fabrication of asymmetric supercapacitors. Sci. Rep. 14, 6045. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56689-9 (2024).

Uyor, U. O., Popoola, A. P. I., Popoola, O. M., Aigbodion, V. S. & Ujah, C. O. Advancing energy storage technology through hybridization of supercapacitors and batteries: a review on the contribution of carbon-based nanomaterials, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 730 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/730/1/012006

Das, S., Senapati, S. & Naik, R. 1D metal telluride heterostructure: A review on its synthesis for multifunctional applications. J. Alloys Compd. 968, 171923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.171923 (2023).

Gao, Y. & Zhao, L. Review on recent advances in nanostructured transition-metal-sulfide-based electrode materials for cathode materials of asymmetric supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 430, 132745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.132745 (2022).

Yilmaz, E. & Yavuz, E. Use of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) in analytical sample Preparation applications. Talanta 266, 125086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2023.125086 (2024).

Chen, D. et al. Metal Selenides for energy storage and conversion: A comprehensive review. Coord. Chem. Rev. 479, 214984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214984 (2023).

Lamiel, C., Hussain, I., Rabiee, H. & Richard, O. Metal-organic framework-derived transition metal chalcogenides (S, se, and Te): Challenges, recent progress, and future directions in electrochemical energy storage and conversion … Metal-organic framework-derived transition metal chalcogenides. Coord. Chem. Rev. 480, 215030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2023.215030 (2023).

Sankar, B. D. et al. Recent advancements in MXene with two-dimensional transition metal chalcogenides/oxides nanocomposites for supercapacitor application – A topical review. J. Alloys Compd. 978, 173481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.173481 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Design strategy for MXene and metal chalcogenides/oxides hybrids for supercapacitors, secondary batteries and electro/photocatalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 464, 214544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214544 (2022).

Dahiya, Y., Hariram, M., Kumar, M., Jain, A. & Sarkar, D. Modified transition metal chalcogenides for high performance supercapacitors: current trends and emerging opportunities. Coord. Chem. Rev. 451, 214265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2021.214265 (2022).

Xavier, J. R., Vinodhini, S. P. & Chandraraj, S. S. Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of CNTs-based multi metal sulphide nanocomposite for supercapacitor applications. J. Clust. 34, 1805–1817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10876-022-02352-0 (2023).

Zhu, X. Recent advances of transition metal oxides and chalcogenides in pseudo-capacitors and hybrid capacitors: A review of structures, synthetic strategies, and mechanism studies. J. Energy Storage. 49, 104148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2022.104148 (2022).

Guo, M. et al. Design, synthesis and application of two-dimensional metal tellurides as high-performance electrode materials. Front. Chem. 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2022.1023003 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Synthesis of NiFe-MOF@NiFeTe nanoparticle-rod heterostructure on nickel foam for high-performance hybrid supercapacitors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 616, 156533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.156533 (2023).

Liu, J., Ren, L., Luo, J. & Song, J. Microwave synthesis of NiSe/NiTe2 nanocomposite grown in situ on Ni foam for all-solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 647, 129093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.129093 (2022).

Bhol, P. et al. Design and fabrication of nickel lanthanum telluride microfibers for redox additive electrolyte-based flexible solid-state hybrid supercapacitor. J. Energy Storage. 65 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.107286 (2023).

Meghanathan, K. L., Parthibavarman, M., Sharmila, V. & Joshua, J. R. Metal-organic framework-derived nickle tellurideporous structured composites electrode materials for asymmetric supercapacitor application. J. Energy Storage. 72 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.108665 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Synthesis of novel bimetallic nickel Cobalt telluride nanotubes on nickel foam for high-performance hybrid supercapacitors. Inorg. Chem. Front. 7, 477–486. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9qi01395d (2020).

Khalafallah, D., Huang, W., Zhi, M. & Hong, Z. Synergistic tuning of nickel Cobalt selenide@nickel telluride core–shell heteroarchitectures for boosting overall Urea electrooxidation and electrochemical supercapattery. Energy Environ. Mater. 7 (1), 12528. https://doi.org/10.1002/eem2.12528 (2024).

Ye, B. et al. Interface engineering for enhancing performance of additive-free NiTe@NiCoSe2 core/shell nanostructure for asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Power Sources. 506 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2021.230056 (2021).

Ameri, B., Zardkhoshoui, A. M. & Hosseiny Davarani, S. S. Engineering of hierarchical NiCoSe2@NiMn-LDH core-shell nanostructures as a high-performance positive electrode material for hybrid supercapacitors. Sustain. Energy Fuels. 4, 5144–5155. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0se00909a (2020).

Shirvani, M., Hosseiny, S. S. & Davarani One-step electrochemical synthesis of Co0.8Fe0.2Se@NiF Sp heres enclosed with nanoparticles and integrated porous FeSe2@NiF as electrode materials for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitor. Energy Fuels. 36, 12271–12284. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c02145 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. MOF derived ZnO/C@(Ni,Co)Se2 core–shell nanostructure on carbon cloth for high-performance supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.130788 (2022).

Moraveji, S., Fotouhi, L., Zirak, M. & Shahrokhian, S. Bimetallic nickel-cobalt nanospheres electrodeposited on nickel foam as a battery-type electrode material for fabrication of asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compds. 946, 169409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.169409 (2023).

Moraveji, S., Fotouhi, L., Shahrokhian, S. & Zirak, M. Electrodeposition of NiCo nanospheres@NiCo2Se4 cauliflower decorated with La2Se3 nanowarm on nickel foam as a battery type electrode for high performance hybrid supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage. 72, 108440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.108440 (2023).

Shahi, M., Hekmat, F. & Shahrokhian, S. 3D flower-like nickel Cobalt sulfide directly decorated grassy nickel sulfide and encapsulated iron in carbon sphere hosts as hybrid energy storage device. Appl. Surf. Sci. 558, 149869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.149869 (2021).

Balasingam, S. K., Lee, J. S. & Jun, Y. Molybdenum diselenide/reduced graphene oxide based hybrid nanosheets for supercapacitor applications. Dalton Trans. 45, 9646–9653. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6DT00449K (2016).

Samal, R. et al. Stabilization of orthorhombic CoSe2 by 2D-rGO/MWCNT heterostructures for efficient hydrogen evolution reaction and flexible energy storage device applications. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 4, 11386–11399. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.1c02205 (2021).

Kong, D., Wang, H., Lu, Z. & Cui, Y. CoSe2 nanoparticles grown on carbon fiber paper: an efficient and stable electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4897–4900. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja501497n (2014).

Bourgeois, S., le Seigneur, P. & Perdereau, M. Study by XPS of ultra-thin nickel deposits on TiO2(100) supports with different stoichiometries. Surf. Sci. 328, 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-6028(95)00022-4 (1995).

Prieto, P. et al. XPS study of silver, nickel and bimetallic silver–nickel nanoparticles prepared by seed-mediated growth. Appl. Surf. Sci. 258, 8807–8813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2012.05.095 (2012).

Wang, C. et al. Honeycomb-like MgCo2O4@ZnCo layered double hydroxide as novel electrode material for high-performance all-solid-state supercapacitors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 612, 155661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.155661 (2023).

Zhu, M., Cai, W., Wang, H., He, L. & Wang, Y. Rational construction of MOF-derived Zn-Co-O/NiCo-LDH core/shell nanosheet arrays on nickel foam for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compds. 884, 160931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.160931 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Co-MOF nanosheet array: A high-performance electrochemical sensor for non-enzymatic glucose detection. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 278, 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2018.09.076 (2019).

Shirvani, M. & Hosseiny Davarani, S. S. Bimetallic CoSe2/FeSe2 Hollow nanocuboids assembled by nanoparticles as a positive electrode material for a high-performance hybrid supercapacitor. Dalton Trans. 51, 13405–13418. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2dt02058k (2022).

Hekmat, F., Shahi, M., Dubal, D. P. & Shahrokhian, S. Hierarchical nickel-cobalt sulfide/niobium pentoxide decorated green carbon spheres toward efficient energy storage. Sustain. Energy Fuels. 6, 3042–3055. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2se00263a (2022).

Amiri, M., Mohammadi Zardkhoshoui, A., Hosseiny Davarani, S. S., Maghsoudi, M. & Altafi, M. K. A high-performance hybrid supercapacitor by encapsulating binder-less FeCoSe2 nanosheets@NiCoSe2 nanoflowers in a graphene network. Sustai Energy Fuels. 6, 3626–3642. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2se00223j (2022).

Dehghanpour, D., Beigloo, F., Mohammadi, A., Hosseini, S. S. & Davarani Boosting energy storage performance: an exploration of tellurium-based Hollow fenicote nanocubes in hybrid supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 474, 145584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.145584 (2023).

Abbasi, S., Hekmat, F. & Shahrokhian, S. Beyond hierarchical mixed nickel-cobalt hydroxide and ferric oxide formation onto the green carbons for energy storage applications. J. Colloid Interf Sci. 593, 182–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2021.02.080 (2021).

Jayababu, N. & Kim, D. Novel Conductive Ag-Decorated NiFe Mixed Metal Telluride Hierarchical Nanorods for High-Performance Hybrid Supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13(17) 19938–19949. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c00506. (2021).

Abdullah, M. et al. Effect of ag content on the electrochemical performance of ag2Te nanostructures synthesized by hydrothermal route for supercapacitor applications. Energy Fuels. 37, 1297–1309. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c03279 (2023).

Pandit, B., Rondiya, S. R., Cross, R. W., Dzade, N. Y. & Sankapal, B. R. Vanadium telluride nanoparticles on MWCNTs prepared by successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction for solid-state supercapacitor. Chem. Eng. J. 429, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.132505 (2022).

Ye, B. et al. In-situ growth of Se-doped nite on nickel foam as positive electrode material for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitor. Mater. Chemi Phys. 211, 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2018.03.011 (2018).

Ali, S. M., Kassim, H. & Amer, M. S. Nanoarchitectonics of Tin telluride: A novel pseudocapacitive material for energy storage application. Mater. Chem. Phys. 301, 127698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2023.127698 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the research Council of Alzahra University for the financial support of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shiva Moraveji: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Lida Fotouhi: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Saeed Shahrokhian: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.Mohammad Zirak: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moraveji, S., Fotouhi, L., Shahrokhian, S. et al. Boosting energy storage performance of ZnCoTe@NiCoSe2 with core-shell structure as an efficient positive electrode for fabrication of high-performance hybrid supercapacitors. Sci Rep 15, 25898 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10106-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10106-x