Abstract

This study retrospectively analyzed medical records of 354 epiretinal membrane (ERM) eyes of 339 patients with 6-month postoperative follow-up to investigate the correlation between ectopic foveal inner layer (EIFL) and the EIFL-based ERM staging system with the anatomical and functional prognosis post pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) combined with cataract surgery. Our results showed preoperative ERM stage (tau-b = 0.196, P < 0.001), disorganization of the retinal inner layers (DRIL) severity (tau-b = 0.248, P < 0.001), central foveal thickness (CFT) (R = 0.387, P < 0.001) and EIFL thickness (R = 0.315, P < 0.001) were positively correlated with logMAR best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at 6-month follow-up. Preoperative ERM stage (tau-b = 0.285, P < 0.001) and DRIL severity (tau-b = 0.239, P < 0.001) were positively correlated with CFT at 6-month follow-up. No significant correlation was found between ERM staging (P = 0.054) with macular edema (ME) resolution at 6 months. More advanced ERM stage (R = 0.494, P < 0.001) and DRIL severity (R = 0.379, P = 0.005) were significantly correlated with persistent newly onset ME at 6 months. Our findings showed that ERM staging based on EIFL could be a simple and intuitive way to predict the short-term functional and anatomical outcomes post-PPV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Idiopathic epiretinal membrane (iERM) is a common vitreoretinal condition caused by the proliferation of glial cells and retinal pigment epithelial cells at the surface of the inner limiting membrane (ILM). The prevalence reported in previous literature ranges from 2.2 to 28.9%, which increases with age1,2. Early ERM usually presents with no obvious symptoms, but as the condition progresses, patients may report metamorphopsia and decreased vision. Govetto et al. first coined the concept of continuous ectopic inner foveal layer (EIFL) on optical coherence tomography (OCT), a continuous hypo- or hyper-reflective band at inner nuclear layer (INL) and inner plexiform layer (IPL), which is visible on all OCT scans centered on the fovea; they further developed a ERM staging system based on the presence of EIFL1. Currently, pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) combined with ERM with or without ILM peeling is a standard procedure for surgical treatment of ERM3, though post-surgery anatomical and functional improvement vary and there is no consensus on a satisfactory clinical marker for predicting the prognosis of ERM eye post-surgery. Previous studies have suggested that the presence of EIFL may suggest poor postoperative visual prognosis2,4. However, there are currently limited clinical studies on the clinical significance of this new ERM staging system for predicting the prognosis of patients post vitrectomy combined with ERM and ILM peeling. This study aimed to provide more insights for the clinical significance and prognosis predicting value of the ERM staging system based on EIFL.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective longitudinal study. This retrospective study was approved by the Ethic Committee of Peking University People’s Hospital and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the need to obtain the informed consent and approval was waived by the Ethic Committee of Peking University People’s Hospital. This study retrospectively enrolled 354 ERM eyes of 339 patients that met the inclusion criteria and no exclusion criteria at Peking University People’s Hospital from January 1, 2020 to October 30, 2023. Inclusion criteria: (1) Clinical diagnosis of unilateral or bilateral ERM. All study eyes underwent combined cataract surgery and PPV with ERM and ILM peeling at our center; (2) Postoperative follow-up time was at least 6 months. Exclusion criteria: (1) Co-existing or previous eye conditions that may cause secondary ERM, such as uveitis, diabetic retinopathy, retinal vascular occlusion, retinal detachment, vitreomacular traction, choroidal neovascularization, age-related macular degeneration, etc.; (2) combined with full-thickness or lamellar macular holes; (3) any other eye conditions that affect vision except age-related cataracts, such as amblyopia, glaucoma, optic neuropathy or trauma; (5) previous PPV history for other eye conditions; (6) poor OCT image quality that affects the measurement of related parameters; (7) for eyes with peripheral retinal tears and retinal degenerations, intraoperative photocoagulation treatment was performed at the discretion of the surgeon; this study did not exclude eyes with peripheral retinal tears and retinal degeneration that were treated with photocoagulation alone during surgery, but eyes that received gas or silicone oil tamponade were excluded. As this was a retrospective study, the decision for the timing for intervention was at the discretion of the doctor with informed consent from the patients, with patient-reported metamorphopsia and decreased vision (no better than decimal visual acuity of 0.6/Snellen visual acuity of 20/32) as factors most weighed in in the decision making process. All post-operative eyes received topical levofloxacin (5 ml:24.4 mg) four times a day for one week; topical 1% prednisolone acetate four times a day for 1 week, then three times a day for 1 week, then twice a day for 1 week, then once a day for 1 week before discontinuation; tropicamide phenylephrine (5 mg/5 mg per 1mL) twice a day for four weeks.

All patients underwent best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), slit lamp microscopy, indirect ophthalmoscopy, fundus color photography, and OCT examinations before surgery, 1month and 6 months after surgery. BCVA was examined using a standard logarithmic visual acuity chart and converted to logarithm of minimal angle resolution (logMAR) visual acuity for statistical analysis. OCT radial scans centering on the fovea were performed with CIRRUS HD-OCT 5000 (Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, California, USA, software version 9.6.1.57321), Avanti RTVue XR 100-2 (Optovue, Fremont, California, USA, software version 2017.1.0.155) or VG200D (SVision Imaging, Ltd., Luoyang, China, software version Van Gogh 3.0). All study eyes received OCT scans with the same devices at the initial visit and all follow-up visits. Fundus color photography was performed using Optos 200Tx (Optos plc, Dunfermline, Scotland, UK) or CLARUS 500 (Zeiss Meditec, Inc., Dublin, California, USA).

In this study, the OCT staging of ERM based on EIFL followed the system proposed by Govetto et al.1: stage 1 included ERM eyes with minimal anatomical disruptions, clearly distinguishable retinal layers and preserved presence of foveal depression; stage 2 included ERM eyes with more progressive anatomical distortions, lost foveal depression but still clearly distinguishable retinal layers; stage 3 included ERM eyes with presence of continuous EIFL and still clearly defined retinal layers; stage 4 included ERM eyes with continuous EIFL, significant retinal thickening and disorganized retina. The thickness of the EIFL and ONL was measured using the caliper tool of the OCT softwares. The grading of disorganization of the retinal inner layers (DRIL) followed the scoring and grading system reported in the literature5: the border between the ganglion cell–inner plexiform layer complex (GCIPL) and INL as well as the border between INL and outer plexiform layer (OPL) were evaluated on OCT scans within the central 2000 μm. GCIPL-INL and INL-OPL boundaries were recorded as distinguishable (score 0) /indistinguishable (score 1) and regular (score 0)/irregular (score 1); grading score of 0 was defined as no DRIL, 1–3 mild DRIL and 4 severe DRIL. Presence of macular edema (ME)/intraretinal cysts and ellipsoid zone (EZ) disruption were noted. Presence of the round or diffuse hyper-reflective area between EZ and interdigitation zone (IZ) at the fovea (Tsunoda sign or “cotton ball” sign), indicating increased traction of the photoreceptors6 was recorded. Before surgery and at each follow-up visit, BCVA, central foveal thickness (CFT), ONL thickness, ERM stage, DRIL severity, presence of EZ disruption, EIFL, and ME were recorded and analyzed. Postoperative BCVA, CFT and presence of ME were indicators used in assessing functional and anatomical prognosis of ERM after surgical intervention.

All surgical procedures were performed by three experienced surgeons (H.M., J.Q. and Y.S.). Surgical procedures were performed as follows: all included eyes underwent phacoemulsification with intraocular lens (IOL) implantation before receiving standard 25G 3-port PPV (CONSTELLATION Vision System, Alcon Laboratories, Inc, Fort Worth, Texas, USA); ERM and ILM were peeled under the assistance of indocyanine green staining. The ILM peeling area was determined at the discretion of the surgeon, which must extend beyond the area of peeled ERM but not beyond the vascular arcades; in cases with minimal ERM-retina adhesion, for example, ILM with 1 to 1.5 disc diameter area centering on the fovea would be removed, Postoperative OCT confirmed that the ERM of all eyes included had been completely removed during surgery.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 26.0.0.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, https://www.ibm.com/spss). Study eyes were divided into four groups according to their preoperative ERM stages based on presence of continuous EIFL for statistical analysis. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used for normality test of continuous variables, and the Levene test was used for variance homogeneity test. For nonparametric tests, Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the two groups of continuous variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to compare the multiple groups. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare the paired samples of continuous variables. Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlation between nonparametric continuous variables; the Kendall Tau-b correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlation between continuous variables and ordinal variables; Goodman-Kruskal Gamma coefficient was used to analyze the correlation between two ordinal variables. Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test was used to test the correlation between ordinal categorical variables and dichotomous variables. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Unless pointed out otherwise, all significance values used in this article have been adjusted by the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests.

Results

This study included 354 eyes of 339 patients (113 male and 241 female) with ERM. At baseline, 13 (3.7%) eyes were stage 1 ERM, 89 (25.1%) were stage 2 ERM, 177 (50.0%) were stage 3 ERM and 75 (21.2%) were stage 4 ERM (Fig. 1). Mean age was 66.8 ± 7.6 (43.0 ~ 89.0) years. Pairwise comparison across groups showed significant difference in age between patients with stage 2 and stage 4 ERM (P = 0.002) but not in other pairwise comparisons. Clinical characteristics of ERM eyes at baseline and 6-month follow-up were shown in Table 1. Age, preoperative BCVA, central foveal thickness (CFT), outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness, EIFL thickness, presence of ME, presence of EZ disruption and presence of “cotton ball” sign all showed significant differences between groups. Stage 4 ERM eyes had worse preoperative logMAR BCVA than stage 1 (P = 0.002), stage 2 (P < 0.001) and stage 3 (P < 0.001) eyes while stage 3 ERM eyes had worse preoperative than stage 1 eyes (P < 0.001). While CFT of stage 2 eyes showed no significant difference compared with stage 1 eyes (P = 0.234), ERM with advanced stages had significantly greater CFT at baseline (P < 0.001 in all pairwise comparisons). ONL thickness was greater in stage 2 (P < 0.001), stage 3 (P < 0.001) and stage 4 (P = 0.037) eyes than stage 1 eyes, but no significant difference was found in ONL thickness in other pairwise comparisons. Stage 4 eyes had greater preoperative EIFL thickness (P < 0.001, 95%CI [-175, -110]) than stage 3 eyes. Stage 4 eyes presented more preoperative ME than stage 1 (P < 0.001 when P < 0.0083 was considered statistically significant), stage 2 (P < 0.001) and stage 3 (P < 0.001), though no significant difference was found between stage 1 and 2 (P = 0.751), stage 1 and 3 (P = 0.548) as well as stage 2 and 3 (P = 0.413) eyes. Interestingly, stage 2 eyes revealed more preoperative EZ disruption than stage 1 (P = 0.008 when P < 0.0083 was considered statistically significant) and stage 4 (P = 0.005) eyes, though no significance difference was found in other pairwise comparisons. More “cotton ball” signs were found in stage 4 eyes than stage 2 (P < 0.001 when P < 0.0083 was considered statistically significant) and stage 3 (P < 0.001) eyes; fewer “cotton ball” signs were found in stage 1 eyes than stage 2 (P = 0.001) and stage 3 (P = 0.005) eyes. All preoperative study eyes were evaluated according to the staging scheme based on presence of continuous EIFL and DRIL severity score, the two staging/scoring system results were positively correlated (G = 0.851, P < 0.001).

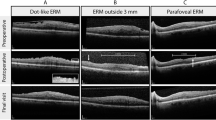

Preoperative and 6-month follow-up OCT B-scans of four ERM patients of different ERM stages. (a) Preoperative OCT B-scan of a stage 1 ERM of a 76-year-old male with a preoperative decimal BCVA of 0.3. All retinal layers were clearly defined and foveal depression was preserved. At 6-month follow-up (decimal BCVA 0.3) OCT B-scan (b) showed retinal thickening, loss of foveal depression and appearance of continuous EIFL (progression to stage 3) after surgical intervention. (c) Preoperative OCT B-scan of a stage 2 ERM with ME of a 61-year-old female with a preoperative decimal BCVA of 0.3. All retinal layers were clearly distinguishable with loss of foveal depression. At 6-month follow-up (decimal BCVA 0.6) OCT B-scan (d) showed recovered foveal depression (regression to stage 1). (e) Preoperative OCT B-scan of a stage 3 ERM of a 77-year-old male with a preoperative decimal BCVA of 0.3. All retinal layers were clearly distinguishable with continuous EIFL (indicated with yellow arrow). At 6-month follow-up (decimal BCVA 0.4) OCT B-scan (f) showed persistent EIFL and retinal thickening. (g) Preoperative OCT B-scan of a stage 4 ERM of a 70-year-old female with a preoperative decimal BCVA of 0.05, showing advanced disorganization of all retinal layers. At 6-month follow-up OCT B-scan (h) showed persistent EIFL and retinal thickening, visual acuity improvement was limited (decimal BCVA 0.25) despite partial recovery of retinal structure (regression to stage 3).

At 6-month postoperative follow-up, logMAR BCVA significantly improved (Z=-14.983, P < 0.001, Wilcoxon signed rank test), CFT decreased (Z=-14.568, P < 0.001), EIFL thickness decreased (Z=-9.185, P < 0.001) and ONL thickness decreased (Z=-8.561, P < 0.001). 150 eyes remained the same stage at 6 months while 16 eyes showed advanced stages (3 eyes advanced from stage 1 to 2, 7 eyes from stage 1 to 3, 6 eyes from stage 2 to 3) and 188 eyes showed stage regression (33 eyes regressed from stage 2 to 1, 28 eyes from stage 3 to 1, 55 eyes from stage 3 to 2, 19 eyes from stage 4 to 2, 53 eyes from stage 4 to 3). During follow-up, 94 (53.1%) of 177 stage 3 eyes while 59 (78.7%) of 75 stage 4 eyes had persistent continuous EIFL.

At 6-month follow-up, logMAR BCVA was significantly worse in stage 4 eyes than stage 2 (P < 0.001) and stage 3 (P = 0.007) eyes, but no statistically significance in other pairwise comparisons; CFT was significant greater in stage 4 eyes than stage 1 (P = 0.013) and stage 2 (P < 0.001) eyes, as well as stage 3 eyes than stage 2 eyes (P < 0.001); ONL thickness was greater in stage 3 eyes than stage 1 (P = 0.042) and stage 2 (P = 0.007) eyes. No significant difference was found in EIFL thickness between groups at 6-month follow-up.

At 6-month follow-up, logMAR BCVA change was significantly greater in stage 2 eyes than stage 4 eyes (adjusted P = 0.009), but no significant difference was found in other pairwise intergroup comparisons. Stage 4 eyes showed greater CFT reduction than stage 1, 2 and 3 eyes (all adjusted P < 0.001) at 6 months. Stage 1 eyes showed less CFT reduction than stage 2 (adjusted P = 0.001) and stage 3 (adjusted P < 0.001) eyes. No significant difference was found in 6-month CFT reduction between stage 2 and 3 eyes (P = 0.089).

The correlation analyses between preoperative clinical characteristics and logMAR BCVA or CFT at 6-month follow-up were performed. Preoperative ERM stage (tau-b = 0.196, P < 0.001), DRIL severity (tau-b = 0.248, P < 0.001), CFT (R = 0.387, P < 0.001) and EIFL thickness (R = 0.315, P < 0.001) were positively correlated with logMAR BCVA at 6-month follow-up while ONL thickness showed no significant correlation (P = 0.647). Preoperative ERM stage (tau-b = 0.285, P < 0.001) and DRIL severity (tau-b = 0.239, P < 0.001) were positively correlated with CFT at 6-month follow-up. Multivariate linear regression was performed with 6-month logMAR BCVA and CFT as dependent variable respectively, and baseline age, sex, logMAR BCVA, CFT, ERM staging, ONL thickness, ME, EZ disruption, cotton ball sign, performing surgeon and OCT device as independent variables. Age (P = 0.030), preoperative CFT (P < 0.001), logMAR BCVA (P < 0.012) and ME (P < 0.001) were found to be correlated with 6-month CFT (model R2 = 0.314, F = 40.028, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 1). Male sex (P = 0.023), preoperative logMAR BCVA (P < 0.001), CFT (P < 0.011), ERM stage (P = 0.006), EZ disruption (P = 0.037) and cotton ball sign (P = 0.013) to be correlated with 6-month logMAR BCVA (model R2 = 0.390, F = 36.907, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 2).

Preoperatively, 155 eyes had ME, ME resolution was achieved in 33 eyes (21.3%) at 1-month post-surgery while ME resolution was achieved in 66 eyes (42.6%) at 6 months post-surgery. The 155 eyes with preoperative ME before surgery were divided into two groups according to whether ME disappeared at the 6-month follow-up after surgery. There was no significant correlation between preoperative ERM staging (P = 0.054) or DRIL severity (P = 0.135) with ME resolution at 6 months. Older age was associated with persistent ME at 6 months (R = 0.248, P = 0.002). Clinical characteristics at baseline and 6-month follow-up in study eyes with or without ME resolution at 6 months were shown in Table 2.

During the follow-up, 57/199 (28.6%) eyes without ME before surgery developed ME 1 month after surgery. Among them, 12 eyes had stage 2 ERM, 42 eyes had stage 3 ERM and 3 had stage 4 ERM. Among these eyes, ME resolution was achieved in 33 eyes (57.9%) while and 24 eyes (42.1% ) had persistent ME 6 months after surgery. Eyes with newly onset ME 1 month after surgery were divided into two groups according to whether ME disappeared at 6 months after surgery for statistical analysis. There was no significant difference in age (P = 1.000), preoperative EIFL thickness (P = 0.250), ONL thickness (P = 0.279), EZ disruption (P = 0.416) and “cotton ball” sign (P = 1.000) between groups. However, preoperative CFT (P < 0.001,95% CI [57, 143]) was significantly greater in non-resolution group; more advanced ERM stage (R = 0.494, P < 0.001, Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test) and DRIL severity (R = 0.379, P = 0.005, Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test) but not older age (P = 0.676) were significantly correlated with persistent newly-onset ME at 6 months.

A total of 199 eyes without preoperative ME were divided into two groups: newly onset ME (57 eyes) and no-ME (142 eyes) groups. Clinical characteristics of eyes without preoperative ME at baseline and at 6 months after surgery were shown in Table 3. Newly onset ME group revealed significantly greater preoperative CFT (P = 0.001, %95CI [-80, -24]) and EIFL (P = 0.020, 95%CI [-40, -3] ). Age was not associated with newly onset ME (P = 0.301). More advanced ERM stage (R = 0.177, P = 0.013) and DRIL severity (R = 0.211, P = 0.003) were correlated with newly onset ME.

In 88 eyes with preoperative EZ disruption, 72 eyes showed persistent EZ disruption and 16 eyes showed resolved EZ disruption at 6 months; 6-month logMAR BCVA showed significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.005, 95% CI [− 0.301, 0.000]). In 252 eyes with preoperative EIFL, 153 showed persistent EIFL and 99 eyes showed resolved EIFL at 6 months; 6-month logMAR BCVA showed significant difference between the two groups (P < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.176, − 0.079]). In 118 eyes with preoperative cotton-ball sign, 57 showed persistent cotton-ball sign and 61 eyes showed resolved cotton-ball sign; 6-month logMAR BCVA showed no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.086).

Dicussions

This study retrospectively analyzed the clinical characteristics of 354 ERM eyes before surgery and 6 months after PPV surgery, and analyzed the clinical feasibility of DRIL severity and ERM staging scheme based on continuous EIFL as predictors for anatomical and functional recovery of ERM eyes. Currently, pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) combined with ERM with or without ILM peeling is a standard procedure for surgical treatment of ERM3, though post-surgery anatomical and functional improvement vary and there is no consensus on a satisfactory clinical marker for predicting the prognosis of ERM eye post-surgery. In recent years, the ERM staging scheme based on ELFL proposed by Govetto et al. provided a possible clinical marker for predicting the prognosis of ERM.

The results of this study showed that the preoperative EIFL thickness was significantly correlated with logMAR BCVA at 6 months postoperatively; post-operative BCVA was significantly worse in stage 4 eyes than stage 2 (P < 0.001) and stage 3 (P = 0.007) eyes at 6 months. Eyes with persistent EIFL showed worse 6-month post-operative BCVA than eyes with resolved EIFL. It should be noted that in this study, due to the difference in preoperative severity of cataract in study eyes, the improvement of postoperative visual acuity cannot exclude the confounding factor of combined cataract surgery. As we deemed it difficult to evaluate how much lens opacity contributed to visual impairment in ERM eyes at baseline, especially for patients with cortical or subcapsular cataract for which not only the severity/grades of cataract but also the specific position of the lens opacity could significantly affect visual acuity, we therefore at the conception of the study design decided to exclude all eyes that did not receive combined phacoemulsification and IOL implantation, removing postoperative age-related or secondary cataracts confounding factors for BCVA. Hence, while improvement in BCVA for each case in our study could not absolutely be contributed to the surgery, the inter-group comparisons of postoperative BCVA, which excluded confounding factor of refractive media opacity caused by cataract, should be valid. Previous studies have shown that presence of EIFL and greater EIFL thickness is associated with poor visual and anatomical2,4,7,8,9, and improvement in BCVA could be associated with postoperative reduction in EIFL thickness8. A study by Gonzalez-Saldivar et al. showed that the visual outcomes of stage 2 ERM was better than that of stage 3 and 4; in their study, 91.7% of stage 2 eyes, 42.3% of stage 3 eyes and 5.2% of stage 4 eyes achieved Snellen visual acuity of 20/40 at 12-month follow-up10, suggesting that the timing of surgical intervention for ERM could be as early as stage 2 to achieve better visual and anatomical outcomes11. Huang et al. further classified stage 3 ERM into two subtypes with type A or B EIFL, type A EIFL being EIFL limited to a hyper-reflective band of IPL while type B EIFL being made of a hyper-reflective band of IPL and a hypo-reflective band of INL, concluding that eyes with type B EIFL had significantly worse visual prognosis12. However, there were also studies suggesting that EIFL thickness or presence of EIFL has no significant correlation with long-term visual prognosis13, despite ERM staging based on EIFL being a relatively reliable indicator14. Coppola et al. also reported that in 58 ERM eyes (ranging from stage 1 to stage 3 eyes), BCVA of eyes with EIFL was better than that of eyes without EIFL at 3 months after surgery with no statistically significant difference15, suggesting that ERM eyes with EIFL probably require a longer time to achieve functional recovery after surgery.

EIFL has also been indicated to be associated with metamorphopsia and could be an independent factor associated with postoperative metamorphopsia16,17,18. Since this study was a retrospective study, this study did not evaluate improvement of metamorphopsia at follow-ups. Mao et al. used M-CHARTS to evaluate the severity of visual distortion in patients with different stages of ERM before and after surgery; the horizontal and vertical metamorphopsia scores of stage 2 and 3 ERMs significantly decreases post-surgery, but not in stage 4 eyes, further suggesting that the timing for surgical intervention ERM should be no later than stage 3 to better alleviate metamorphopsia in ERM eyes16.

Cicinelli et al. reported that ME in ERM eyes was associated with a more advanced ERM stage and older age19. In this study, eyes with preoperative ME that achieved ME resolution had greater baseline CFT (P = 0.001); and even though more advanced ERM stage and DRIL severity showed no significant correlation with ME resolution, they were significantly correlated with persistent newly onset ME at 6 months. Also consistent with previous reports19, this study also showed older age was associated with persistent ME at 6 months. More eyes with preoperative ME showed ME resolution at 6 months than at 1 month, indicating that the recovery time for ERM eyes with ME could be longer. Cases with newly onset ME in this study suggested that early intervention in mild ERM cases should be considered with caution, though the fact that eyes with newly onset ME had greater preoperative CFT values that no-ME group also suggested the timing for surgically intervention should probably precede significant retinal thickening to avoid further post-surgery anatomical complications. Kwon et al. divided ERM eyes with or without intraretinal cystoid spaces (IRC) into three groups, A, B and C (absence, IRC within 3 mm and 6 from the fovea) and found that widely distributed IRCs were associated with poor BCVA. Yang et al. classified ERM eyes with ME into those with cystoid ME (CME, IRCs located in the INL and OPL) and those with microcystic ME (MME, IRCs mainly located in the INL), and found that MME, primarily found in advanced stages ERM, was associated with poor visual prognosis20. In our study, we did not find significant difference in 6-month BCVA in eyes with or without resolved ME. More future studies focusing on morphological types of ME and quantification of ME and their relationship with postoperative parameters of ERM eyes may help in clarifying the effects of ME on functional changes of ERM eyes. It has also been observed that in most stage 3 and 4 eyes in this study, EIFL persisted after surgery despite the reduction of EIFL thickness. The persistence of EIFL could be one of the reasons for the limited anatomical and functional improvement in these patients.

In our study, 57/199 (28.6%) eyes without ME before surgery developed ME 1 month after surgery, of which 24 eyes (12.1% of all eyes without preoperative ME) showed persistent ME at 6 months. We found that newly onset ME group showed greater preoperative CFT and EIFL, and that more advanced ERM stage and DRIL severity were associated with postoperative onset ME. It should be noted that in our study all eyes received combined cataract and PPV surgeries. Previous studies have shown a higher prevalence of postoperative onset ME in eyes that received combine cataract and PPV surgery or PPV with consecutive cataract surgery than eyes that received PPV surgery alone in ERM eyes21,22. Therefore, as more advanced ERM stage, greater preoperative CFT and EIFL might be indicators of higher risk for postoperative ME, it is possible that in ERM eyes with these characteristics might benefit more from PPV surgery alone when lens opacity does not affect surgical procedures, with cataract surgery at a second moment, preferably further away from the time of PPV.

The pathogenesis mechanism of formation of EIFL is still unclear. In this study, 13 eyes with stage 1 or 3 ERMs before surgery developed EIFL during postoperative follow-ups. The formation of EIFL after the removal of ERM tractional force suggests that factors other than ERM traction contributes to the formation of EIFL. Previous studies suggested that activation of Müller cells after surgery might play a role4. Baek et al. found that the increased vitreous level of M2 macrophage markers in eyes with EIFL, suggesting that activation of glial cell proliferation by M2 macrophages may contribute to EIFL formation23.

Changes in ONL thickness have also been noted. Preoperatively, ONL thickness was greater in stage 2 (P < 0.001), stage 3 (P < 0.001) and stage 4 (P = 0.037) eyes than stage 1 eyes; at 6-month follow-up, the ONL thickness was significantly decreased than that before surgery, which is consistent with previous report by Doguizi et al.24. Govetto et al. reported that the thickness of the ONL increased in ERM eyes that progressed from stage 1 to stage 2, while the thickness of the ONL decreased in eyes that progressed from stage 2 to stage 31. Coppola et al. suggested that the ONL thickness was thinner in ERM eyes with continuous EIFL, indicating that progressive ONL thinning may imply centripetal displacement of the inner retinal layers and outer layers centrifugal shift to the perifoveal area15. Takage et al. reported the correlation between ONL changes with metamorphopsia25. Further studies are needed in the future to further clarify the impact of ONL thinning and ONL ectopia on metamorphopsia and visual prognosis in eyes with ERM.

DRIL has been identified as a biomarker for functional outcomes in eyes with diabetic macular edema (DME), suggesting the feasibility of application of DRIL scoring in eyes with ERM. The study by Zur et al. suggested that eyes with severe DRIL showed worse anatomical and visual outcomes over 12-month follow-up5. The results of this study showed that more advanced preoperative ERM stages and DRIL severity were correlated with greater CFT, persistent ME and worse BCVA at 6-month follow-up, suggesting that DRIL scoring system and ERM staging scheme based on EIFL could be helpful in predicting the anatomical and visual outcomes of ERG eyes post-surgery, consistent with conclusions of previous studies. In this study all eyes were evaluated with both DRIL and ERM staging schemes, results from this study showed that the grading results of the two systems were consistent and correlated, suggesting predictive values of both methods. However, compared with DRIL scoring system, ERM staging scheme based on EIFL is simpler and more intuitive, and the EIFL thickness itself could be a potential predictor for prognosis of ERM eyes.

The strengths of this study include: relatively large sample size with representation from all four ERM stages; head-to-head comparison between EIFL-based ERM staging and DRIL severity; relatively comprehensive preoperative parameters analyzed in the study and exploration in possible risk factors for persistent ME and postoperative newly-onset ME. The limitations of this study include: (1) retrospective study design; (2) sample size difference across groups; (3) limited follow-up time. The conclusions drawn from this short-term study may not fully represent late visual or anatomical outcomes. Microvasculature such as vessel density (VD), perfusion density (PD) and foveal avascular zone (FAZ) parameters have also been previously indicated to be associated with visual prognosis of ERM26; as OCT angiography (OCT-A) was not standard investigative protocol for ERM at our center, OCT-A perimeters were not included in the analyses of this study. Due to the retrospective nature of the study design, study eyes were examined using three different devices, and possible inter-device difference might affect parameter measurement in this study. We did try to minimize the influence by using the same device for each study eye in follow-up visits, though future studies using single OCT device are needed to further validify our results. This study also did not factor in potential factors regarding surgical techniques, for example ILM peeling extent, or surgeon experience. It also should be noted that the small sample size for stage 1 ERM eyes (13 eyes) in our study limited power for inter-group comparisons. In the future, more prospective studies with larger samples and longer follow-up time are needed to further confirm the clinical and predictive values of ERM staging based on EIFL. In recent years, with the advent of artificial intelligence, machine learning has increasingly been used in predicting disease outcomes in ophthalmology. Machine learning models have been developed to predict postoperative visual acuity with preoperative OCT perimeters including EIFL thickness27,28. More future studies could focus on possible clinical diagnostic and predictive use of machine learning in ERM.

In conclusion, this study showed that the ERM staging scheme based on EIFL could be a simple and intuitive way to predict the short-term functional and anatomical outcomes after ERM surgery; more advanced ERM stages and DRIL severity were positively correlated with logMAR BCVA, greater CFT and persistent newly-onset ME at 6 months, while greater preoperative CFT and EIFL thickness were positively correlated with logMAR BCVA at 6 months.

Data availability

The data analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Govetto, A., Lalane, R. A., Sarraf, D., Figueroa, M. S., Hubschman, J. P. & rd, & Insights into epiretinal membranes: presence of ectopic inner foveal layers and a new optical coherence tomography staging scheme. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 175, 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2016.12.006 (2017).

Yang, X. et al. Effects of ectopic inner foveal layers on foveal configuration and visual function after idiopathic epiretinal membrane surgery. Retina 42, 1472–1478. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000003495 (2022).

Flaxel, C. J. et al. Idiopathic epiretinal membrane and vitreomacular traction preferred practice pattern(r). Ophthalmology 127, P145–P183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.09.022 (2020).

Govetto, A. et al. Functional and anatomical significance of the ectopic inner foveal layers in eyes with idiopathic epiretinal membranes: surgical results at 12 months. Retina 39, 347–357. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000001940 (2019).

Zur, D. et al. Disorganization of retinal inner layers as a biomarker for idiopathic epiretinal membrane after macular surgery-the dream study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 196, 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2018.08.037 (2018).

Tsunoda, K., Watanabe, K., Akiyama, K., Usui, T. & Noda, T. Highly reflective foveal region in optical coherence tomography in eyes with vitreomacular traction or epiretinal membrane. Ophthalmology 119, 581–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.08.026 (2012).

Gesualdo, C. et al. Multimodal assessment of the prognostic role of ectopic inner foveal layers on epiretinal membrane surgery. J. Clin. Med. 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12134449 (2023).

Park, Y. G., Hong, S. Y. & Roh, Y. J. Novel optical coherence tomography parameters as prognostic factors for stage 3 epiretinal membranes. J. Ophthalmol. 2020 (9861086). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/9861086 (2020).

Mavi Yildiz, A., Avci, R. & Yilmaz, S. The predictive value of ectopic inner retinal layer staging scheme for idiopathic epiretinal membrane: surgical results at 12 months. Eye (Lond). 35, 2164–2172. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-021-01429-w (2021).

Gonzalez-Saldivar, G., Berger, A., Wong, D., Juncal, V. & Chow, D. R. Ectopic inner foveal layer classification scheme predicts visual outcomes after epiretinal membrane surgery. Retina 40, 710–717. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000002486 (2020).

Karasu, B. & Celebi, A. R. C. Predictive value of ectopic inner foveal layer without internal limiting membrane peeling for idiopathic epiretinal membrane surgery. Int. Ophthalmol. 42, 1885–1896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-021-02186-1 (2022).

Huang, Y. et al. Subtyping stage 3 epiretinal membrane: A comprehensive study of ectopic inner foveal layers architecture and its clinical implications. Br. J. Ophthalmol. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo-2023-324517 (2024).

Mansilla, R. et al. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography insights into idiopathic epiretinal membrane surgery outcomes. Retina 45, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000004258 (2025).

Kim, B. H., Kim, D. I., Bae, K. W. & Park, U. C. Influence of postoperative ectopic inner foveal layer on visual function after removal of idiopathic epiretinal membrane. PLoS One. 16, e0259388. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259388 (2021).

Coppola, M. et al. The visual outcomes of idiopathic epiretinal membrane removal in eyes with ectopic inner foveal layers and preserved macular segmentation. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 259, 2193–2201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-021-05102-6 (2021).

Mao, J. et al. Changes in metamorphopsia, visual acuity, and central macular thickness after epiretinal membrane surgery in four preoperative stages classified with Oct b-scan images. J. Ophthalmol. 2019 (7931654). https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7931654 (2019).

Yanagida, K. et al. Ectopic inner foveal layer as a factor associated with metamorphopsia after vitrectomy for epiretinal membrane. Acta Ophthalmol. 100, 775–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.15092 (2022).

Miyazato, M. et al. Predictive factors for postoperative visual function in eyes with epiretinal membrane. Sci. Rep. 13, 22198. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49689-8 (2023).

Cicinelli, M. V. et al. Associated factors and surgical outcomes of microcystoid macular edema and cone bouquet abnormalities in eyes with epiretinal membrane. Retina 42, 1455–1464. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000003492 (2022).

Yang, X. et al. Clinical features and prognosis in idiopathic epiretinal membranes with different types of intraretinal cystoid spaces. Retina 42, 1874–1882. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000003537 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Metabolomic comparison followed by cross-validation of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to reveal potential biomarkers of diabetic retinopathy in Chinese with type 2 diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 986303. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.986303 (2022).

Frisina, R. et al. Cystoid macular edema after Pars plana vitrectomy for idiopathic epiretinal membrane. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 253, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-014-2655-x (2015).

Baek, J. et al. Elevated m2 macrophage markers in epiretinal membranes with ectopic inner foveal layers. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 61, 19. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.61.2.19 (2020).

Doguizi, S., Sekeroglu, M. A., Ozkoyuncu, D., Omay, A. E. & Yilmazbas, P. Clinical significance of ectopic inner foveal layers in patients with idiopathic epiretinal membranes. Eye (Lond). 32, 1652–1660. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-018-0153-9 (2018).

Takagi, S. et al. Assessment of the deformation of the outer nuclear layer in the epiretinal membrane using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. BMC Ophthalmol. 19, 113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-019-1124-z (2019).

Yu, H. Y., Na, Y. J., Lee, S. C. & Lee, M. W. Characteristics of the macular microvasculature in idiopathic epiretinal membrane patients with an ectopic inner foveal layer. Retina 43, 574–580. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000003710 (2023).

Irie-Ota, A. et al. Predicting postoperative visual acuity in epiretinal membrane patients and visualization of the contribution of explanatory variables in a machine learning model. PLoS One. 19, e0304281. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304281 (2024).

Crincoli, E. et al. New artificial intelligence analysis for prediction of long-term visual improvement after epiretinal membrane surgery. Retina 43, 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1097/IAE.0000000000003646 (2023).

Funding

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82301211 and 81800847) and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (J230028). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and supervision, H.M, Y,S; Resources (i.e. patients), data collection and curation, J.T., J.L., J.Q., X.S., H.Q., T.Q., W.Y., H.Y., J.H., Y.C., J.L., M.Z., and X.L.; Writing – original draft and formal analysis J.T.; Writing – review & editing, H.M., J.L., and Y.S.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, J., Liu, J., Qu, J. et al. Ectopic inner foveal layer as post pars plana vitrectomy prognostic predictor in eyes with idiopathic epiretinal membrane. Sci Rep 15, 25066 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10861-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10861-x