Abstract

The aim of this study was to look for mediators of the relationship between established risk factors (trauma and stress) and the symptoms of premenstrual disorders. The study was divided into two parts: with a retrospective (N = 339; aged 18–47, M = 24,23; SD = 5.23) and a prospective (N = 76; aged 18–44, M = 25.85; SD = 6.09) measure of premenstrual symptoms. The tested mediators were rumination, external locus of control, and trait anger. While all variables were significantly correlated, only trait anger mediated the relationship between stress and retrospectively measured premenstrual symptoms (indirect effect B = 0.29; 95%CI: 0.13–0.47; β = 0.07), and the association of trauma with both retrospectively recalled (indirect effect B = 0.19; 95%CI: 0.09–0.31; β = 0.06) and prospectively measured premenstrual symptoms (indirect effect B = 0.35; 95%CI: 0.07–0.75; β = 0.08). Locus of control and ruminations seem to be primarily related to one’s subjective assessment of premenstrual symptoms severity, and trait anger seems to be a factor related to the actual symptoms’ severity. These findings can contribute to our better understanding of premenstrual disorders and may be used in developing their more effective therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While the majority (up to 90%) of women experience mild premenstrual symptoms1, at times these symptoms become so severe that they disrupt daily functioning, resulting in a diagnosis of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) or its more severe form, premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). PMS occurs in about 20–30% of menstruating people2, while PMDD is less (but still) common, affecting 3–8% of naturally cycling individuals3. Both PMS and PMDD are characterized by the occurrence of symptoms only in the (approximately) last week of the menstrual cycle and their cessation in a few days after the menses. To diagnose PMDD, at least one of the so-called core emotional symptoms (depressive mood, anxiety, emotional lability, irritability) must be present and the sum of the symptoms must be at least five4. PMS and PMDD are related to many problems in daily functioning, decreased life quality, lower achievements (both in school and work), lower sexual satisfaction, and they often co-occur with other mental disorders and suicidal tendencies5,6,7,8,9,10.

However, in spite of the high prevalence of premenstrual disorders and their significant negative impact on lives of menstruating people, psychological research addressing the mechanisms and determinants of premenstrual disorders is still lacking11.

Some of the confirmed risk factors for the development of premenstrual disorders are the experience of trauma and increased stress1,12,13. This relationship has been confirmed by both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies14. Moreover, an elevated stress reactivity during the luteal phase of the cycle in women with PMDD was observed14. It was shown that in comparison with healthy menstruating persons, people with PMDD had tendency to present higher perceived stress during the luteal phase than in the follicular phase of the menstruation cycle15. This reactivity could be associated with a reduced response of allopregnanolone (the main metabolite of progesterone, which increases gabaergic transmission) to acute stress and changes in HPA axis function (although the evidence is still inconclusive14).

There is little research on the psychological connections (mediators) between trauma and stress and the severity of PMDD symptoms. It was shown that the relationship between childhood trauma and these symptoms may be mediated by depression16, difficulties in regulating emotions17, trait anger and pessimistic attributional style18. However, these studies were cross-sectional and used only retrospective measures of premenstrual symptomatology. Additionally, in two of them the samples were also relatively small17,18.

Nevertheless, it is plausible that other psychological factors may also play a role in the development of PMDD in individuals who have undergone traumatic life events. Rumination is a kind of self-focus in which a person concentrates on own distress, its symptoms, and causes, but not solutions19,20. It differs from worrying by concentration on the present and the past rather than the future. Rumination is considered a maladaptive strategy20, and while it was traditionally connected with depression, it was also shown to be related to other mental disorders19. Research has indicated that individuals with premenstrual disorders have a heightened tendency to ruminate19,21, as well as that rumination may mediate the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and premenstrual distress in healthy women22. Ruminations are also associated with and often triggered by stressful events, and occur in post-traumatic stress23,24. Moreover, stress was shown to be related to higher momentary rumination in people with PMDD but not in healthy women, regardless of the cycle phase, which suggests this can be a trait-like feature15. While the study cited did not examine the possible mediation effect, its results suggest that such indirect effect might exist.

Another possible variable that might play a role in the development and maintenance of premenstrual disorders in high risk individuals is locus of control (LOC). It represents the degree to which a person perceives things happening to them as a result of their own actions (internal LOC) or as an effect of external influences (external LOC25). External LOC appears logically associated with the sense of uncontrollability commonly experienced in traumatic and stressful situations, and stronger belief in the significance of external influences. Indeed, research has indicated that external LOC is linked to greater psychological distress after trauma26. Moreover, external LOC is correlated with depressive symptoms27, which are often present in PMDD and clinical PMS; as well as with various subtypes of premenstrual symptoms in healthy women28. It was also shown that women with PMDD have a more external LOC than women without premenstrual disorders29 and that LOC may become more external before menstruation in people with PMS30.

Finally, increased irritability, anger, and interpersonal conflicts are among core emotional symptoms of PMDD and PMS2,4. It was demonstrated that women with PMS present higher level of constant anger and lower anger control than women without premenstrual disorders31. Higher trait anger was also shown in women with PMDD and was related to the severity of PMDD symptoms32. Recently, trait anger was also identified as possible partial mediator of the relationship between stress and trauma and premenstrual symptomatology measured retrospectively18. Moreover, a meta-analysis indicated that traumatic experiences can be related to heightened feelings of anger and hostility33. Additionally, associations of perceived stress with trait anger have also been shown34.

Objectives

The aim of the current study was to examine three possible mediators of the relationship between trauma and heightened stress with the severity of the symptoms of premenstrual disorders measured retrospectively (screening tool) and prospectively. Based on the conceptual models of premenstrual disorders and the results of previous research we hypothesised that tendency to rumination, external locus of control, and trait anger mediate the relationship between risk factors and PMS/PMDD symptoms severity as measured both retrospectively and prospectively. Prospective diagnosis is not only required for the formal diagnosis of premenstrual disorders2,4, but it is also considered a golden standard for their research11. Retrospective measure is more susceptible to (memory) bias11 but – apart from the screening purpose – it can be used as an indicator of one’s beliefs about own premenstrual symptoms or their subjective assessment. It may be valuable to explore which variables seem to be more important for the retrospectively and prospectively measured premenstrual symptoms.

Method

Materials and procedure

The study was performed from January to June 2023 and consisted of two stages: a cross-sectional one conducted online on volunteers recruited from the general sample and a prospective diagnosis part on a selected sub-sample of people presenting high scores on the screening tool measuring premenstrual symptoms.

Both parts of the study were conducted using the Qualtrics platform. Participants were recruited through advertisements published on social media. They were informed about the aim of the study, time needed to complete it, and their rights. All participants gave their informed consent to participate in the study by ticking a box on the form. Then they answered questions about exclusion criteria and demographics. If they did not meet inclusion criteria, that is: they were younger than 18 years, did not menstruate, or used contraceptives, the form automatically closed, thanking them for the will to participate and explaining why they cannot take part in the study. The rest then filled the questionnaires measuring study variables. Another exclusion criterion was a diagnosis of any ongoing mental disorder. However, confirming answer did not close the form automatically to avoid excluding participants diagnosed with PMDD.

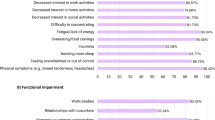

Premenstrual symptoms were measured with the Polish translation of the Premenstrual Symptoms Screening Tool (PSST35), which is a widely used retrospective measure of premenstrual disorders. PSST consists of 19 questions, 14 addressing DSM-5 symptoms of PMDD (“Do you experience some or any of the following premenstrual symptoms, which start before your period and stop within a few days of bleeding?”) and five considering the impact of these symptoms on various domains of functioning (e.g., “Have your symptoms, as listed above, interfered with your work efficiency or productivity?”). Respondents use a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from “not at all” to “severe.” The Cronbach’s alfa for the PSST in the sample was very good: α = 0.92.

Tendency to ruminate was measured with the Polish adaptation of the Rumination- Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ36,37). RRQ consists of 24 questions and two sub-scales: 12 questions measuring reflection and 12 measuring rumination (e.g., “I often find myself re-evaluating something I’ve done”). Participants mark their answers using a five-point Likert-type scale. The Polish version of RRQ has very good psychometric qualities37. For this study, only the Rumination sub-scale scores were calculated. The Cronbach’s alfa for the Rumination scale in the sample was very good: α = 0.91.

Locus of Control was measured with the Delta Questionnaire38, a tool based on Rotter’s Internal-External Control Scale and other popular measures38. Delta consists of 24 questions, with 14 aimed at measuring locus of control (e.g., “Very often I feel that I have no influence on what happens to me”) and 10 serving as control questions. It has good psychometric properties38. The Cronbach’s alfa in the sample was satisfactory: α = 0.64.

Trait anger was measured with the Polish adaptation of State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory Revised (STAXI-239,40). STAXI-2 consists of 57 items and 10 sub-scales measuring state and trait anger as well as anger expression and anger control (e.g., “I have a fiery temper”). Polish version of STAXI-2 has very good psychometric properties40. For the purpose of this study only Trait Anger (Angry Temperament and Angry Reaction) sub-scale score was calculated. The Cronbach’s alfas in the sample were good: 0.82 for the whole trait anger sub-scale, 0.84 for Angry Temperament, and 0.70 for Angry Reactions.

Perceived stress was measured with the Perceived Stress Scale short form (PSS-441,42). It is a short, 4-item measure of stress experienced in the last month (e.g., “In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?”). Participants mark their responses using a five-point (0–4) scale, ranging from “never” to “very often.” PSS-4 showed good psychometric properties in the previous research42,43. Cronbach’s alfa in the sample was satisfactory: α = 0.70.

Traumatic experiences were measured with the Traumatic Experiences Checklist (TEC44; Polish translation: R. Tomalski). TEC consists of a list of 29 traumatic experiences (e.g., “Did this happen to you: a threat to life from illness, surgery, or accident?”). Respondent marks the one that happened to them and specify the impact it left on them (on a 5-point Likert-like scale). Cronbach’s alfas in the sample were good: 0.80 for traumatic experiences scale and 0.83 for impact scale.

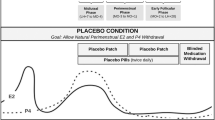

After participants filled in the cross-sectional study, their scores on Premenstrual Symptoms Screening Tool were calculated. Individuals whose (1) answers indicated that they may have premenstrual disorders (PMDD or PMS); and who (2) expressed willingness to participate in the second part of the study by providing their e-mail address, were contacted (with those potentially suffering from PMDD contacted first). All the conditions of the prospective diagnosis part of the study were explained and the participants were presented with the instruction on how to properly fill in the symptoms diaries. If they upheld their decision to participate in this part of the study during a meeting with the researcher, they were added to a mailing list and received links to fill in symptoms dairies for two months, so that two whole perimenstrual periods (7 days prior to 10 days after the menses) were recorded. The link with the tool were send to the responders on each evening to measure the symptoms presented on that day. In exceptional cases the form also allowed the participants to fill in the dairy for the previous day (which was noted).

Only one measure was used in the longitudinal part of the study: the Daily Rating of Severity of Problems (DRSP45). The DRSP is a widely used tool recommended by the International Association for Premenstrual Disorders (IAPMD). It measures the DSM-5 criteria of PMDD in prospective, daily rating. DRSP was obtained and translated for this study with the permission of authors. The process included back-translation performed by a translator with an experience in the field of psychology. DRSP scores were calculated by a research assistant who was trained beforehand with the accordance to recommendations of IAPMD and Endicott and colleagues45.

Criteria for PMDD were (a) at least 5 symptoms marked as at least severe (4 out of 6) through at least two days in the last week of the luteal phase (b) full clearance of symptoms in postmenstrual phase (days 4–10 of follicular phase; calculated prospectively) (c) at least 30% of relative symptoms change from the pre- to the postmenstrual phase. For PMS similar criteria were used but the absolute number of 5 symptoms was not required and the relative change level was established at 20% (as PMS symptoms usually are of lesser severity). Additionally, participants were asked each day if they experienced stressful situations and days with marked stressors were excluded from the calculations as suggested by Endicott and colleagues45. At the end of this part, participants were provided with the result of the assessment of their symptom diaries.

A single score of the average severity of premenstrual symptoms severity was calculated. It was done with the use of the so-called Summary Scores of DRSP45. Symptoms from both premenstrual weeks were added (Summary Scores for each day) and the mean of the intensity of symptoms in both cycles was calculated. The mean was used instead of the sum to amend for the missing records from some days. Only one score was calculated because the intensity of particular symptoms between each menstrual cycle may vary in the same person. Moreover, the aim of the study was not to track the impact of risk factors and mediators on symptom levels from month to month (for which a two-month measurement would have been too short), but to see if anger, ruminations, and locus of control mediate the association of risk factors with overall premenstrual symptom severity.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed, written consent was obtained from all participants (in electronic form from the participants of the cross-sectional part of the study, as signed documents from the sub-sample of people participating in the prospective diagnosis part). The study was approved by the Jagiellonian University Institute of Psychology Research Ethics Committee (KE/66_2022).

Participants

Participants for the cross-sectional part of the study were recruited by advertisements posted on social media. In total, 339 people (333 female, three non-binary, three preferred not to specify or chose “other”), aged 18–47 (M = 24,23; SD = 5.23) participated in this part of the study. Participants whose scores on PSST indicated possible diagnosis of a premenstrual disorder (either PMS or PMDD), declared no other mental disorder diagnosis and expressed the will to participate in the longitudinal part of the study were invited to fill in the symptom diaries (DRSP). In total, 94 people confirmed their willingness and started filling in DRSP but 18 people (19.15%) resigned during the longitudinal study. The final sample comprised of 76 people (75 female, one non-binary), aged 18–44 (M = 25.85; SD = 6.09). None of the participants in both parts of the study reported other mental health diagnosis (apart from one person in the cross-sectional part who reported depression in remission and thus was not excluded).

All participants were volunteers, and those who participated only in the cross-sectional study did not receive any compensation. For filling in the symptom diaries, participants were financially compensated with the amount of 100 Polish zloty (net; about 25 USD), they also received evaluation of their diaries.

The calculation of the sample size for mediation analysis was based on G*Power Tool46 (for one predictor and three parallel mediators, power [1-β] = 0.95, effect size ρ2 = 0.20 [f2 = 0.25]; minimal n = 80) and Fritz and MacKinnon’s47 recommendations (for bootstrap method, β effect size = 0.39, power [1-β] = 0.80; minimal n = 78). The sufficient sample size was determined to be about 80 people.

Analysis plan

To test the study hypotheses, the correlation and mediation analyses were performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 29.0 and PROCESS package. Firstly, the Kołmogorow-Smirnow normality test was used to assess the distribution of study variables. Correlation analysis was then conducted with Spearman’s rho test. Finally, mediation analyses (using model 4 in PROCESS) were performed to explore the possible intermediate variables of the relationship between stress/trauma and premenstrual symptoms. Mediation models were tested separately for each predictor using parallel models resulting in a total of four mediation analyses (two in the cross-sectional and two in the prospective diagnosis parts of the study). MacKinnon’s48 conditions were used for mediation analysis: (1) significant association between risk factors and premenstrual symptoms; (2) significant association between mediators and premenstrual symptoms while trauma and stress were controlled; (3) a significant coefficient for the indirect path between trauma, stress, or both and premenstrual symptoms through mediators. For mediation analysis the indirect effects significance was calculated with bootstrap method (5,000 samples) for 95% confidence intervals.

Results

The statistics for study variables both in the cross-sectional and the longitudinal parts of the study are presented in Tables 1 and 2. According to the Kołmogorow-Smirnow normality test, most variables did not have normal distribution, with an exception of the premenstrual symptoms intensity in longitudinal study (p = 0.077). Thus, non-parametric tests were performed.

According to screening with PSST, 90 people (26.6%) did not present any premenstrual disorder, 110 (32.4%) had PMS, and 139 (41%) had PMDD. In the group of 76 participants of the longitudinal part of the study (who were all identified as possibly having premenstrual disorders), 27 (35.5%) met the diagnostic criteria of PMS and 39 (51.3%) of PMDD. For 10 people (13.2%) a prospective diagnosis did not confirm a premenstrual disorder. None of them presented the course of symptoms suggesting a premenstrual exacerbation of a pre-existing disorder (that is: affective, cognitive, or somatic symptoms present during the whole cycle and worsening premenstrually) Thus, the concordance of screening diagnosis with prospective diagnosis was 86.9% (13.2% of participants were considered as meeting diagnostic criteria of different premenstrual disorders by PSST and DRSP). The correlation between PSST and DRSP scores (mean intensity from premenstrual weeks) was moderate: rho = 0,64 (p < 0,001; N = 76). Additionally, 36 participants (47.4%) experienced a peak in mood symptoms around ovulation (calculated as 14 days before the start of the next menstrual cycle, i.e., before the menses).

Correlations between premenstrual symptoms, stress, trauma, locus of control, tendency to ruminate, and trait anger in cross-sectional and longitudinal study

Correlation analyses were done with Spearman’s rho test. In the cross-sectional part of the study, all correlations between study variables were significant (see Table 3). The results of prospective diagnosis part were more interesting: rumination and locus of control were not significantly related to premenstrual symptoms or trauma (rumination was also not correlated with stress and anger) but all other correlations were stronger than in the cross-sectional part (for detailed results see Tables 3 and 4).

Intergroup differences

Additionally, in the current study we also calculated the intergroup differences between participants with prospectively confirmed diagnosis of PMS (n = 27) or PMDD (n = 39; the “PMS/PMDD group,” N = 66) and those who either did not present premenstrual disorders in prospective diagnosis (n = 10) or had very low scores in screening (n = 88), thus indicating not to have any premenstrual disturbances (the “no diagnosis group,” N = 98). U Mann-Whitney test was performed and showed that PMDD and PMS women had significantly higher scores in all study variables than the “no diagnosis group” (with an exception of locus of control — their scores were significantly lower, indicating significantly more external LOC). For the detailed results see Table 5.

Mediation analysis

Mediation analysis was performed separately for the retrospectively and the prospectively measured premenstrual disorders.

As for PSST scores, trait anger significantly mediated the relationship between trauma and premenstrual symptoms, and locus of control was a borderline significant mediator of said relationship. Only trait anger mediated the relationship between perceived stress and PSST scores. Detailed results can be seen in Figs. 1 and 2.

In the group of prospectively diagnosed individuals (N = 76), the results were even more interesting: contrary to the hypothesis, locus of control and rumination failed to mediate the relationship between both trauma and stress, and premenstrual symptoms. Only one mediation path was significant: the relationship between trauma and premenstrual symptoms through trait anger. Detailed results can be seen in Figs. 3 and 4.

Discussion

In the current study, we predicted that locus of control, rumination, and trait anger will mediate the relationship between the risk factors (trauma and stress) and the intensity of retrospectively and prospectively measured symptoms of premenstrual disorders. The hypotheses were only partially confirmed.

In the cross-sectional part of the study, which implemented retrospective measure of premenstrual symptoms, all variables were significantly, positively correlated (the correlations with locus of control were negative, because higher sores on the “Delta” questionnaire indicate internal LOC); however, these correlations were moderate or even weak. In the group of individuals whose premenstrual symptoms were prospectively diagnosed, all the correlations were visibly stronger, with an exception of the relations of rumination and LOC with other variables which were non-significant.

The results of mediation analysis also only partially confirmed the hypotheses: trait anger emerged as the only significant mediator of the relationship between trauma and stress, and premenstrual disorders in both parts of the study (in the case of stress: solely when premenstrual symptoms were assessed retrospectively, not prospectively). In the cross-sectional part of the study mediation between trauma and retrospectively recalled premenstrual symptoms through locus of control was approaching statistical significance (association between LOC and PSST scores while trauma was controlled at a borderline significance level: p = 0.069; lower border of confidence intervals of the indirect effect starting at zero), although not reaching it.

The results thus seem to confirm the possible role of trait anger in the development and maintenance of premenstrual disorders, at least in trauma survivors. This finding is also in line with the previous research: both showing an increase in anger and hostility after traumatic experiences33, and the higher trait anger in individuals with PMDD32, and with our previous retrospective study showing that trait anger mediates the relationship between risk factors and premenstrual symptoms18. It is also important to note that increased irritability and interpersonal conflicts not only are among the so-called core emotional symptoms of PMDD4, but they also seem to be the most common of these symptoms (while depression had long been believed to be the most common14). In light of both previous research and our present study, it seems plausible that heightened trait anger may be a very important characteristic of individuals suffering from premenstrual disorders, however more research is still needed.

While both locus of control and rumination have been significantly correlated with PSST scores (i.e., the retrospective measure of premenstrual symptoms), their correlation with mean scores on DRSP was insignificant and they were not mediators in any of the models tested. They thus appear to be primarily related to one’s subjective assessment of symptom severity and to be more important to retrospective recall than to actual, daily tracked levels of symptoms. The results of a recent research by Tauseef and colleagues49 are in line with this finding: they found that rumination predicted baseline negative affectivity but not affective cyclicity in individuals with premenstrual symptoms.

LOC and rumination may play some role in the interpretation and evaluation of symptoms, influencing their recalling. Rumination is a memory strategy in which a person concentrates on the negative side of past events. Thus, it is likely that rumination should be especially important to the recall of symptoms (and possibly – their exaggeration), not their prospectively measured severity. The association of external locus of control with retrospectively but not prospectively measured symptoms may be less obvious but not inexplicable. First of all, some studies have shown that LOC may became more external before menstruation or that women with PMDD have less internal LOC than healthy subjects20,29. Therefore, external LOC could be seen more like symptom itself, not a mechanism of premenstrual disorders. Moreover, both internal and external LOC may be related to symptoms severity when they (the symptoms) are experienced: internal LOC may be related to some kind of self-blaming for symptoms in some individuals (as they, for example, see their angry outbursts or emotional lability as something they are doing) and external LOC may increase the feelings of symptoms incomprehensibility or unfairness. Thus there are no direct link between the externality-internality of LOC and prospectively measured premenstrual symptoms. However, external LOC may be related to the retrospective recall of their severity exactly because menstruating individuals with more external locus of control perceive these symptoms as more uncontrollable and overwhelming when they think about their previous menses, while people with more internal LOC may not interpret their symptoms as symptoms but as their own actions.

It is also important to note that none of proposed variables (rumination, locus of control, trait anger) mediated the relationship between stress and the average severity of prospectively measured premenstrual symptoms. This may suggest that stress-related higher level of trait anger is more important for recall or self-assessment of symptoms (retrospective measurement), but not for their more objectively measured severity. But this finding may also be related to more temporary effect of perceived stress, which was only assessed once, at the base-line. This one measure of stress might not be representative for the daily changes in perceived stress in individuals participating in the prospective part of the study during two months. The lack of significant mediation could also be attributed to the small size of the prospectively studied group, leading to moderate statistical power in the analyses, or the limited variation in the levels of studied variables within this group. It is important to note that participants with prospectively confirmed diagnosis and without diagnosis differed significantly in the levels of every study variable.

Viewed from another angle, the lack of mediation by ruminations and locus of control may also indicate that although PMDD is classified in the DSM-5 as a mood disorder4 and shares many similarities with depression or bipolar disorder50,51, some of its psychological mechanisms may be different. Some studies on the efficacy of psychotherapy in the treatment of PMDD have shown insufficiently satisfactory effects of both cognitive-behavioural therapy and pharmacotherapy52 and results of our present study may shed some light on these findings. Perhaps we should focus on different mechanisms in the treatment of premenstrual disorders, such as addressing anger and impulsiveness rather than cognitive and behavioural tendencies typical for depression.

It is crucial to emphasise that there is still no complete theory of PMDD and we still do not understand this disorder fully53. Therefore, more research is needed on the topic, especially prospective studies on larger groups, so we can better catch the complex interrelationships between the different risk factors and correlates of premenstrual disorders. Studies like this one may help us to better comprehend the psychological functioning of people suffering from PMS and PMDD, and thus might help improving the existing therapeutic interventions for premenstrual disorders. Currently, treatment of PMS and PMDD is based on pharmacotherapy and hormonal contraception, which, however, is only a symptomatic treatment and sometimes leads to problematic side effects2,3. Alternative therapeutic forms are still not generally available, and there is a lack of psychotherapeutic interventions dedicated to PMS and PMDD with proven efficacy11,52. Findings of this study suggest that psychotherapy of premenstrual disorders should include interventions aimed at anger management, dealing with irritability, and conflict resolution. Relaxation techniques or dialectical behaviour therapy skills aimed at anger and aggression54 could be beneficial for at least some PMDD patients.

Limitations

This study is not free of some limitations. Some of the differences in the results of the cross-sectional and the prospective parts of the study, which were attributed to the method of the measurement, could be also related to the unexplored differences between samples. The group which participated in the prospective diagnosis part of the study was relatively small, thus possibly lacking statistical power to detect some relationships between variables (as the minimal required sample size required to detect medium effects would be around 80 people, and for small effects – around 190 people46). Additionally, it only consisted of individuals presenting high levels of symptoms on the screening tool. Moreover, participants only declared lack of somatic problems or illnesses, and their hormone levels were not assessed, thus it is impossible to rule out that some of their symptoms were actually caused by problems other than “pure” PMS or PMDD. It is also important to note that while online assessment has many advantages, it also entails some problems, especially with the representativeness of the sample and generalization of the result: lack of the interviewer makes it impossible to clear some of potential participant’s questions, only those with an internet access could participate in the study, and as participants were volunteers, it is also very probable that some people (e.g., already suffering from premenstrual disorders) were more interested – and thus more likely – to participate in the study (which may be reflected in the very high prevalence rate of PMDD in the sample). Furthermore, perceived stress was only measured once, while its level might have changed during the two month-period of the second part of the study, thus limiting the value of mediation analysis in the case of this risk factor and prospectively measured premenstrual symptoms (in fact, days in which participants experienced heightened stress were excluded from the calculation of DRSP scores). Finally, prospective part of the study only lasted for a period of two menstrual cycles. It was dictated by practical reasons and financial constraints, but tracking the trajectory of symptoms for a longer period of time could have provided some interesting and more detailed data.

Conclusions

Despite a few limitations, this study provides some valuable insight of possible determinants of the course and maintenance of premenstrual disorders. So far, there is little research concentrating on the psychological mechanisms and determinants of the functioning of individuals with PMS or PMDD, especially with a prospective measure of premenstrual symptoms.

This study demonstrated the role of trait anger in premenstrual disorders in a prospective examination. Not only naturally cycling individuals with PMDD and PMS experience angry outbursts as a symptom of their disorders, they also present higher trait anger levels than non-PMDD women (this finding is in line with a study of Saglam & Basar31) and trait anger may be the intermediate variable connecting traumatic experiences with a higher risk of developing premenstrual disorders.

In this study locus of control and tendency to ruminate were related only with retrospectively but not prospectively measured premenstrual symptoms, while trait anger mediated the relationship between trauma and premenstrual symptoms in both parts of the study. This suggests that LOC and rumination may be more important for subjective assessment of premenstrual symptoms than their actual severity, for example influencing recalling the symptoms – which might provide some insights on the mechanism of memory bias in retrospective measure of premenstrual disorders (however, this results can be also contributed to the limited statistical power in the prospective diagnosis sample). Trait anger, on the other hand, seems to be an important factor (maybe even a psychological mechanism) related to the actual symptoms severity.

While PMDD is traditionally associated with affective disorders (especially depression), its psychological mechanisms seem to be different. The potential practical implication of this study is the suggestion to involve working with anger in PMDD psychotherapy (which should of course also include relaxation techniques, psychoeducation, and normalisation of feelings of anger in women with PMDD, as anger is still stigmatised and repressed as a stereotypically unfeminine emotion).

.

Data availability

All data associated with this research may be assessed via e-mail to corresponding author. Data is not stored in open-access database to protect participants’ from accidental violation of confidentiality as it includes sensitive information.

References

di Lanza, T. & Pearlstein, T. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Psychiatr Clin. North. Am. 40 (2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2017.01.002 (2017).

Biggs, W. S. & Demuth, R. H. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am. Fam Physician. 84 (8), 918–924 (2011).

Ismaili, E. et al. Fourth consensus of the international society for premenstrual disorders (ISPMD): auditable standards for diagnosis and management of premenstrual disorder. Arch. Womens Ment Health. 19 (6), 953–958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0631-7 (2016).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Durairaj, A. & Ramamurthi, R. Prevalence, pattern and predictors of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) among college girls. New. Indian J. OBGYN. 5 (2), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.21276/obgyn.2019.5.2.6 (2019).

Hardy, C. & Hardie, J. Exploring premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) in the work context: a qualitative study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 38 (4), 292–300 (2017).

Heinemann, L. A. J., Do Minh, T., Filonenko, A. & Uhl-Hochgräber, K. Explorative evaluation of the impact of premenstrual disorder on daily functioning and quality of life. Patient: Patient-Centered Outcomes Res. 3 (2), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.2165/11533750-000000000-00000 (2010).

Hong, J. P. et al. Prevalence, correlates, comorbidities, and suicidal tendencies of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in a nationwide sample of Korean women. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 47 (12), 1937–1945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0509-6 (2012).

Nowosielski, K., Drosdzol, A., Skrzypulec, V. & Plinta, R. Sexual satisfaction in females with premenstrual symptoms. J. Sex. Med. 7 (11), 3589–3597 (2010).

Wittchen, H. U., Becker, E., Lieb, R. & Krause, P. Prevalence, incidence and stability of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the community. Psychol. Med. 32 (1), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291701004925 (2002).

Eisenlohr-Moul, T. & Premenstrual Disorders A primer and research agenda for psychologists. Clin. Psychol. 72 (1), 5–17 (2019).

del Mar Fernández, M., Regueira-Méndez, C. & i Takkouche, B. Psychological factors and premenstrual syndrome: A Spanish case-control study. PLoS ONE. 14 (3), e0212557. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212557 (2019).

Pilver, C. E., Levy, B. R., Libby, D. J. & Desai, R. A. Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma characteristics are correlates of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Arch. Women Ment Health. 14 (5), 383–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-011-0232-4 (2011).

Hantsoo, L. & Epperson, C. N. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: epidemiology and treatment. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 17 (11), 87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0628-3 (2015).

Beddig, T., Reinhard, I. & Kuehner, C. Stress, mood, and cortisol during daily life in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). Psychoneuroendocrinology 109, 104372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.10437 (2019).

Younes, Y., Hallit, S. & Obeid, S. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder and childhood maltreatment, adulthood stressful life events and depression among Lebanese university students: a structural equation modeling approach. BMC Psychiatry. 21, 548. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03567-7 (2021).

Azoulay, M. et al. Childhood trauma and premenstrual symptoms: the role of emotion regulation. Child. Abuse Negl. 108, 104637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104637 (2020).

Antosz-Rekucka, R. & Prochwicz, K. The relationship between trauma, stress, and premenstrual symptoms: the role of attributional style and trait anger. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol., online first, 1–14. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2024.2377099

Craner, J. R., Sigmon, S. T., Martinson, A. A. & McGillicuddy, M. L. Premenstrual disorders and rumination. J. Clin. Psychol. 70, 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22007 (2014).

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. in Ruminative Coping with Depression in Motivation and self-regulation across the Life Span. 237–256 (eds Heckhausen, J. & Dweck, C.) (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Roomaney, R. & Lourens, A. Correlates of premenstrual dysphoric disorder among female university students. Cogent Psychol. 7 (1), 1823608. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2020.1823608 (2020).

Sigmon, S. T., Schartel, J. G., Hermann, B. A., Cassel, A. G. & Thorpe, G. L. The relationship between premenstrual distress and anxiety sensitivity: the mediating role of rumination. J. Ration. -Emot Cogn. -Behav Ther. 27 (3), 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-009-0100-6 (2009).

De Lissnyder, E. et al. Cognitive control moderates the association between stress and rumination. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 43 (1), 519–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.07.004 (2012).

Szabo, Y. Z., Warnecke, A. J., Newton, T. L. & Valentine, J. C. Rumination and posttraumatic stress symptoms in trauma-exposed adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anxiety Stress Copin. 30 (4), 396–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2017.1313835 (2017).

Rotter, J. B. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol. Monogr. 80 (1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976 (1966).

Papanikolaou, V. et al. Relationship of locus of control, psychological distress, and trauma exposure in groups impacted by intense political conflict in Egypt. Prehosp Disaster Med. 28 (5), 423–427. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X13008601 (2013).

Yu, X. & Fan, G. Direct and indirect relationship between locus of control and depression. J. Health Psychol. 21 (7), 1293–1298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314551624 (2016).

Lane, T. & Francis, A. Premenstrual symptomatology, locus of control, anxiety and depression in women with normal menstrual cycles. Arch. Women Ment Health. 6 (2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-003-0165-7 (2003).

Christensen, A. P., Board, B. J. & Oei, T. P. S. A psychosocial profile of women with premenstrual dysphoria. J. Affect. Disord. 25 (4), 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0327(92)90083-I (1992).

O’Boyle, M., Severino, S. K. & Hurt, S. W. Premenstrual syndrome and locus of control. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 18 (1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.2190/hmnx-9v7j-652x-pwj4 (1989).

Saglam, H. Y. & Basar, F. The relationship between premenstrual syndrome and anger. Pak J. Med. Sci. 35 (2), 515–520. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.35.2.232 (2019).

Soyda Akyol, E., Karakaya Arısoy, E. Ö. & Çayköylü, A. Anger in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: its relations with premenstrual dysphoric disorder and sociodemographic and clinical variables. Compr. Psychiatry. 54 (7), 850–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.03.013 (2013).

Orth, U. & Wieland, E. Anger, hostility, and posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults: A meta-analysis. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 74 (4), 698–706. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.698 (2006).

Thomas, S. P. & Williams, R. L. Relationships among perceived stress, trait anger, modes of anger expression and health status of college men and women. Nurs. Res. 40 (5), 303–307. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199109000-00022 (1991).

Steiner, M., Macdougall, M. & Brown, E. The premenstrual symptoms screening tool (PSST) for clinicians. Arch. Women Ment Health. 6 (3), 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-003-0018-4 (2003).

Trapnell, P. D. & Campbell, J. D. Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: distinguishing rumination from reflection. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 76 (2), 284–304. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.76.2.284 (1999).

Słowińska, A., Zbieg, A. & Oleszkowicz, A. Kwestionariusz Ruminacji-Refleksji (RRQ) Paula D. Trapnella i Jennifer D. Campbell-polska Adaptacja metody. Pol. Forum Psychol. 19 (4), 457–478. https://doi.org/10.14656/PFP20140403 (2014).

Drwal, R. Ł. Adaptacja Kwestionariuszy Osobowości (PWN, 1995).

Spielberger, C. D. STAXI-2 State-Trait-Anger Expression Inventory-2.Professional Manual (PAR, 1999).

Bąk, W. Pomiar stanu, cechy, Ekspresji i kontroli złości. Polska Adaptacja Kwestionariusza STAXI-2. Pol. Forum Psychol. 21 (1), 93–122. https://doi.org/10.14656/PFP20160107 (2016).

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24 (4), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404 (1983).

Atroszko, P. A. The structure of study addiction: Selected risk factors and the relationship with stress, stress coping and psychosocial functioning. Unpublished doctoral thesis (University of Gdańsk, Gdańsk, Poland, (2015).

Vallejo, M. A., Vallejo-Slocker, L., Fernández-Abascal, E. G. & Mañanes, G. Determining factors for stress perception assessed with the perceived stress scale (PSS-4) in Spanish and other European samples. Front. Psychol. 9, 37. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00037 (2018).

Nijenhuis, E. R. S., Van der Hart, O. & i Kruger, K. The psychometric characteristics of the traumatic experiences questionnaire (TEC): first findings among psychiatric outpatients. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 9 (3), 200–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.332 (2002).

Endicott, J., Nee, J. & Harrison, W. Daily record of severity of problems (DRSP): reliability and validity. Arch. Women Ment Health. 9, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-005-0103-y (2006).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A. G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods. 41, 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 (2009).

Fritz, M. S. & MacKinnon, D. P. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol. Sc. 18 (3), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x (2007).

MacKinnon, D. Introduction To Statistical Mediation Analysis (Routledge, 2008).

Tauseef, H. A. et al. Is trait rumination associated with affective reactivity to the menstrual cycle? A prospective analysis. Psychol. Med. 54 (8), 1824–1834. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291723003793 (2024).

Pearlstein, T. Bipolar disorder and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: comorbidity conundrum. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 83 (6), 43545. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.22com14573 (2022).

Yonkers, K. A. The association between premenstrual dysphoric disorder and other mood disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 58 (suppl 15), 19–25 (1997).

Kleinstäuber, M., Witthöft, M. & Hiller, W. Cognitive-behavioral and Pharmacological interventions for premenstrual syndrome or premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings. 19, 308–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-012-9299-y (2012).

Hofmeister, S. & Bodden, S. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am. Fam Physician. 94 (3), 236–240 (2016).

Frazier, S. N. & Vela, J. Dialectical behavior therapy for the treatment of anger and aggressive behavior: A review. Aggress. Violent. Beh. 19 (2), 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.02.001 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Jakub Antosz-Rekucki, MA, for proofreading.

Funding

This research has been supported by a Research Support Module grant from the Faculty of Philosophy under the Strategic Programme Excellence Initiative at Jagiellonian University. Article Processing Charges were funded by a grant from the Strategic Program Excellence Initiative at the Jagiellonian University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A.R. and K.P. designed the study. R.A.R. conducted the research, collected and analysed the data, and wrote the first version of the manuscript. K.P. supervised the work and revised the manuscript. R.A.R. and K.P. wrote the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

Public health significance

This study suggests that rumination and locus of control may influence how naturally cycling individuals perceive the severity of their premenstrual symptoms, rather than the actual intensity of the symptoms themselves. In contrast, trait anger appears to be more directly involved in the development of premenstrual disorders. This indicates that therapeutic interventions should focus more on addressing anger, irritability, and conflict resolution.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Antosz-Rekucka, R., Prochwicz, K. The role of trait anger, rumination, and locus of control in the relationship between trauma, stress, and premenstrual disorders. Sci Rep 15, 25361 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11146-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11146-z