Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of a 6-week “staircase sprinting” (SS) with or without blood flow restriction (BFR) on body composition, anaerobic power, and leg muscle strength in physically inactive college students. Twenty-two physically inactive college students (11 males and 11 females) were randomly assigned to an experimental group (SS-BFR, n = 12) and a control group (SS, n = 10). Participants in both groups received SS snacks 3 days per week (3 times per day) for 6 weeks. The interval between each SS was greater than two hours. The SS-BFR group wore the BFR device during SS, which was measured using the estimated Arterial Occlusion Pressure(AOP). A 40% AOP was used in weeks 1–3 and increased to 50% AOP in weeks 4–6. Normal data were analyzed using one-way covariance analysis (ANCOVA), and non-normal data were analyzed using nonparametric ANCOVA (Quade’s test). After the 6-week intervention, no intra- or inter-group differences in body composition were observed between the two groups (p > 0.05). Anaerobic power showed a significantly lower decrease in fatigue index (Pi) in the SS-BFR group than in the SS group (p = 0.047, ƞ²P = 0.191, 95% CI [0.075, 11.739]). However, no significant main effects were observed for peak power (PP), mean power (MP), and minimum power (MinP) between the groups (p > 0.05). The results of the isokinetic muscle strength test showed that, except for the right knee extensor muscle strength at 60 °/s, which exhibited a significant between-group difference (p = 0.033, F = 5.273), no other results demonstrated significant between-group main effects (p > 0.05). Surface electromyography (sEMG) results showed no significant between-group main effects for changes in vastus medialis (p = 0.093, ƞ²P = 0.141, 95% CI [-0.838, 9.965]) and vastus lateralis (p = 0.527, ƞ²P = 0.021, 95% CI [-5.629, 10.663]). Applying BFR during the SS period seems to enhance the participants’ leg muscle strength and their ability to resist fatigue during anaerobic exercise. However, the effectiveness of this intervention must be determined in future studies, considering factors such as cuff pressure, gender and sample size.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, being physically inactive has been increasingly highlighted as a significant public health challenge, strongly associated with an increased risk of developing a range of chronic diseases, and can have a profound negative impact on an individual’s quality of life and life expectancy1. The World Health Organization recommends that adults engage in at least 75 to 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and at least two sessions of resistance training per week to counteract the harmful effects of being physically inactive2. However, it is worrying that around a third of adults worldwide do not meet this recommended standard3 with lack of time often cited as a significant barrier to participation in physical activity4. Evidence suggests moderate-to-vigorous physical activity of any duration is associated with improved health outcomes, even when total physical activity is below the guideline-recommended levels5,6. Therefore, exploring some time-saving and efficient exercise strategies that promote physical activity and improve health may be helpful.

Exercise Snacks (ES) have recently received research attention as a time-saving and efficient mode of exercise that allows individuals to perform multiple times between daily routines and is usually defined as a separate exercise session that lasts less than 1 min per session or consists of multiple 1-minute exercises7. A 60-step stair climbing, performed three days a week, three times a day, improved peak oxygen uptake in sedentary young people compared with the non-exercising group8. Compared to moderate-intensity continuous training, 6 weeks of “all-out” staircase sprinting (SS) performed 3 days a week, 3 times a day was similarly effective to moderate-intensity continuous training (40 min × 60–70% Heart Rate) in improving cardiorespiratory fitness9. In addition, SS improves the femoral artery shear pattern in healthy men10. Given the benefits of improving cardiorespiratory fitness, the effects may also extend to body composition, muscular strength, and anaerobic power. However, there is currently little research in this area. Regarding muscle adaptation, several studies have found that resistance ES significantly promotes muscle strength and increases muscle cross-sectional area in older adults11. In contrast, in adults, the results appear to be equivocal. For example, Wun12 found that after 6 weeks of ES using the Wingate protocol in a decentralized format, significant improvements in isokinetic strength testing were only observed in the 30°/s maximum voluntary contraction force of the participants’ dominant lower limb flexors. In physically inactive young adults, a single 30-second full sprint ES performed 5 days per week (1 time per day) did not significantly improve muscle strength13. Regarding body composition, ES was observed to improve body weight and body fat in sedentary obese people14, but in older adults, resistance ES did not appear to affect their body composition11. In addition, no studies seem to have observed improvements in anaerobic capacity with SS snacking, as ES is usually performed at the fastest possible or “all-out” level, and anaerobic capacity also plays an important role in energy metabolism. Therefore, monitoring anaerobic capacity would be beneficial in further understanding the effects of ES on physical health. However, as noted in previous studies13, single doses of ES are usually low, which may require longer cycles to induce adequate physical adaptation. A recent review suggests a direction of investigation combining ES with specific physiological perturbations (e.g., Blood Flow Restriction, BFR)15, which provides an interesting perspective for our study, i.e., could adding BFR additionally stimulate improvements in body composition, muscular strength, and anaerobic power?

BFR training involves external constrictive devices (usually blood pressure cuffs or elastic wraps) on the proximal musculature of the limb (upper arms, thighs) to reduce arterial blood flow and significantly impede venous return16. BFR has been shown to improve muscular strength when combined with sprint interval training significantly17 and anaerobic performance when combined with small games18. In addition, when BFR is combined with low-intensity exercise, surface electromyography (sEMG) has shown that action potential amplitudes are activated at a higher discharge rate19. Despite the additional operational steps of BFR, its ability to rapidly increase muscle adaptation through metabolic stress may make its combination with ES a practical option for additional improvements in physical fitness. As no such studies have been reported in the existing literature, this study aimed to test whether SS combined with BFR could improve body composition, muscle strength, and anaerobic power in college students who are physically inactive. We hypothesized that the SS program combined with BFR would improve body composition, muscle strength, and anaerobic power more than SS alone.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-three participants (including 12 males) were enrolled. one male participant withdrew midway through the study for personal reasons, and 22 participants eventually completed the study(Fig. 1). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) did not meet the World Health Organization defined requirements of at least two muscle-strengthening training sessions and 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise per week and ≥ 6 h of sedentary time per day, (2) participants were ≥ 18 years of age, (3) were free of cardiovascular or other chronic diseases, and(4) All participants were non-smokers and had no history of alcohol consumption. In addition, they confirmed no use of hormonal medications (e.g., corticosteroids, thyroid medications) for at least 3 months before study participation.

The following conditions were excluded: (1) another exercise during the intervention or muscle pain or discomfort caused by the intervention.

All participants signed an informed consent form and were fully informed of the test procedure and data collection method. This research has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Physical Education and Sports Science at Fujian Normal University, and has been conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Study design

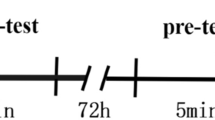

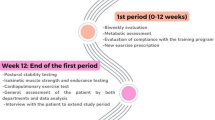

Participants were randomly assigned to an experimental group (SS-BFR, n = 12) and a control group (SS, n = 10). Baseline characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The control group trained 3 times a day, 3 days a week, for 6 weeks (96 steps of “all-out” SS). Each SS interval was > two hours. Participants were asked to exercise on alternate days as exercise was only performed 3 days a week. In addition, participants were asked to complete training in the morning (9:00–12:00) and afternoon (2:00–5:00).

The SS-BFR group, in addition to following the training protocol of the control group, was also required to wear a BFR device (width 10 cm, length 108 cm, nylon material; Theratools, Guangzhou, China) on the leg. To calculate the cuff pressures for this study, the formula developed by Loenneke20 for predicting lower extremity blood flow restriction (BFR) was used: Arterial occlusion pressure (AOP, mmHg) = 5.893 (thigh circumference) + 0.734 (diastolic blood pressure (DBP)) + 0.912 (systolic blood pressure (SBP)) – 220.046. First, the thigh circumference of all participants was measured at 33% of the distance from the groin crease to the top of the patella. Then, SBP and DBP were collected from the participants at rest. After collecting the data, the AOP was calculated for each participant. According to Patterson’s16 study, a cuff pressure of 40–80% AOP is usually reasonable and safe. In this study, 40% AOP(SS-BFR = 96.72 ± 9.94, SS = 92.00 ± 10.34) was used as the initial pressure value. From the 4 Fourth week onwards, it was increased to 50% AOP(SS-BFR = 120.91 ± 12.43, SS = 115.00 ± 12.93) to ensure the improvement of the body’s adaptability.

To reduce potential bias, each intervention was performed in a fixed setting. Specifically, all participants implemented the exercise intervention in a 6-story building in the School of Physical Education and Sports Science, Fujian Normal University. There are 24 steps on each floor of the building. Each step is 15 cm high, 154 cm wide, and 28 cm long. The BFR was performed as follows: prior to the SS, the researcher tied a cuff around the participant’s thigh and used a pressurised to increase the pressure to the specified level, and then the participant performed a stair climbing sprint in response to the researcher’s command to “all out”. After reaching 96 steps, the researcher removed the pressure from the cuff. The intervention protocol for the participants is shown in (Fig. 2).

Test metrics

The primary outcome of this study was the changes in body composition, anaerobic power and leg muscle strength from baseline to after the intervention. For exploratory purposes, secondary outcomes evaluated the median frequency changes of the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis muscles during the SS process.

Body composition

The participants’ height was measured in the morning on an empty stomach. Then, the participants’ weight and body fat percentage were accurately measured using a body composition tester (Inbody 370, Korea), from which the body mass index (BMI), which is obtained by dividing weight (kg) by height (m2), was calculated. To ensure the accuracy of the results, participants were required to wear light clothing and remove their shoes, socks, and any jewellery during the test. After the body composition test, the participants’ thigh circumference, SBP, and DBP were measured. Thigh circumference was then measured as 33% of the distance from the groin crease to the top of the kneecap. For data collection, SBP and DBP were recorded using Omron (760 J, Japan). Participants were asked to sit still for 5 min before testing to maintain a resting state, and then blood pressure was taken evenly from the participant’s left hand. Blood pressure measurements were taken twice with an interval of 1 min between measurements.

Anaerobic power

Participants first warmed up for 5 minutes on an unpowered stationary bike. Using an anaerobic power bike (Monark 894E, Sweden)21participants were assessed for anaerobic power. Brake weight type was determined by calculating 7.5% (0.075 kg body mass-1 ) of the participant’s body weight, and the seat height was adjusted to align with the participant’s hip joint. The seat height was adjusted to align with the participant’s hips, and the weight basket was pre-calibrated by the researcher to the target mass before the start of the test (error ± 5 g). The test mode for the weight basket is ‘basket initially down.‘The system automatically determined whether a valid resistance trigger was present by a 1-second difference in pedal frequency (> 10 rpm) between the front and back of the basket and repeated the test if the criterion was not met. Once the values were calibrated, the participant performed a 30-s Wingate test, during which the researcher provided continuous verbal encouragement to ensure that the participant maintained maximum force. At the end of the test, the participant’s peak power (PP), mean power (MP), minimum power (MinP), peak cadence (RMP), and fatigue index (Pi) were recorded; Pi was calculated by subtracting MinP from PP to determine the power drop, then dividing the power drop by PP and multiplying by 100.

Isokinetic muscle strength

Participants performed a 5-minutes warm-up on an unpowered stationary bike, followed by 3 min of dynamic stretching of the lower extremity joints. The multi-joint isometric testing and training system (HUMAC NORM 2009, USA) tested participants’ knee flexor and extensor strength. Two speeds of 60°/s and 180°/s were utilized, respectively. Before each isokinetic test, calibration was performed to ensure the uniformity of test standards. The configuration and positioning of the dynamometer were as follows: the dynamometer was oriented at 40°, the seat tilt was set at 0°, the seat orientation was adjusted to 40°, and the seat back tilt was calibrated between 70° and 85°. The axis of rotation is found to pass through the lateral femoral condyle in the sagittal plane. The preparation position was full knee flexion (90°). After setting the range of knee flexion/extension movement (0° to 90°), participants performed four pre-trials of self-perceived 50-80% force generation prior to testing at each angular velocity. Formal testing followed, with participants performing five peak torque tests of the knee flexors and extensors at 60 °/s full power. After 30 s of rest, 15 trials of average torque testing of the knee flexors and extensors at 180 °/s full power were performed. Data were analyzed by recording the highest of 5 repetitions at 60 °/s and the mean of 15 repetitions at 180 °/s22.

Surface electromyography

Participants were asked to perform a 96-step “all-out” SS test. The SS was performed as quickly as possible after hearing the “start” command, and numerical changes in the muscle signals of the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis were recorded during the participants’ SS using a 16-channel surface electromyography system (BTS FREEEMG, Italy) with an acquisition frequency of 1000 Hz. Fast Fourier Transform. According to the SENIAM guidelines23 prior to data collection, participants’ legs were depilated, disinfected with 75% alcohol, and abraded with fine sandpaper in order to place the sEMG electrodes, which were then connected to the sEMG sensors. After data collection, the EMG signals were processed using the native software (BTS EMG Analyzer 2.9.40.0), which automatically full-wave rectified and normalized the raw sEMG data during pre-processing. The sEMG data were band-pass filtered using Butterworth filtering (high pass filtered at 20 Hz, low pass filtered at 450 Hz), and medium frequency was calculated for all muscles.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0. Normality was tested for all data using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Paired-sample t-tests were used to verify within-group differences for data that met normality, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for non-normality. One-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to analyze baseline data as a covariate and post-intervention data as the dependent variable to validate between-group differences. Levene’s test determined the homogeneity of variance. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The significance level of the data was set at P < 0.05, and 95% confidence intervals were reported. Effect sizes were reported using partial ƞ², with 0.02, 0.06, and 0.14 representing small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively24. For leg muscle strength, since the 60 °/s right extensor, 60 °/s right flexor, 60 °/s lift flexor, 180 °/s right extensor, and 180 °/s lift flexor data were not normally distributed, nonparametric ANCOVA (Quade’s test) was used to calculate the differences between groups after the intervention.

Results

Primary outcomes

Body composition

The results (Table 2) showed that, after the 6-week intervention, there were no significant differences between the two groups of participants in terms of body weight, body fat percentage and BMI(p > 0.05).

Anaerobic power

The results for anaerobic power (Table 3) showed that, for both groups of participants, PP, MP, MinP and Max Speed did not reveal a significant main effect between groups(p > 0.05). However, a significantly greater decline was found in the SS group than in the SS-BFR group in Pi (p < 0.05).

Isokinetic muscular strength

The 60 °/s isokinetic muscle strength test showed (Table 4) a significant main effect between groups for the right extensor(p < 0.05). However, no significant intergroup differences were observed for the 60 °/s lift extensor, 60/s right flexor, and 60°/s lift flexor(p > 0.05). The 180 °/s isokinetic muscle strength test revealed no significant differences in all indicators between the two groups of participants (p > 0.05).

Secondary outcome

The surface electromyography in Table 5 shows the within-group changes in vastus medialis and vastus lateralis in the SS-BFR group were 5.84% and − 5.18%, respectively. There were no significant between-group main effects for changes in vastus medialis and vastus lateralis(p > 0.05).

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the effects of six weeks of SS with or without BFR on body composition, leg muscle strength, and anaerobic power in physically inactive college students. The results showed no differences between the two groups of participants after the intervention. However, a significantly lower anaerobic power (p < 0.05) was observed in the SS-BFR group than in the SS group. There were no differences in any of the other metrics. A between-group main effect was observed in leg muscle power only in the 60 °/s right extensor. The SS-BFR group was significantly higher than the SS group (p < 0.05). However, avoidance sEMG data showed no between-group differences in vastus medialis or vastus lateralis(p > 0.05).

No changes in body composition (weight, body fat percentage, BMI) were observed in participants in the SS-BFR group in the current study. Similarly, a study of low-intensity walking combined with BFR found no improvement in body composition in physically active individuals25, which is consistent with our findings. Another study also found that combining low-intensity resistance training with BFR did not improve body composition in untrained individuals26. The reason for this finding may be related to the intervention cycle. This is because ES was found to have a significant effect on improving body composition in sedentary obese adults14 and adolescents with type 1 diabetes27 during longer intervention cycles (≥ 12 weeks). Therefore, longer intervention cycles may be beneficial to observe the efficacy of SS combined with BFR in improving body composition.

Regarding anaerobic power, a significantly lower decrease in Pi was observed in the SS-BFR group than in the SS group only after the 6-week intervention. This may be related to increased muscle resistance to fatigue induced by BFR application during SS. Application of BFR during isokinetic resistance exercise exacerbated muscle fatigue compared to controls without BFR, suggesting a strong but transient effect of BFR on neuromuscular function28. In chronic studies, however, BFR improves skeletal muscle fatigue resistance by prolonging resting muscle glycogen and ATP levels, improving muscle fatigue tolerance29. Another study showed that implementing BFR during rest periods can induce metabolic stress, locally improving muscle fatigue resistance30. Conversely, we did not observe a significant difference in the other anaerobic power indices (p > 0.05). It was hypothesized that this may be related to cuff pressure. A study by Amani-Shalamzari31 found that running at high cuff pressures (240 mmHg) was more likely to improve anaerobic power in physically active college women. It was hypothesized that there is a relationship between the magnitude of cuff pressure and the improvement in anaerobic power, i.e., the higher the cuff pressure, the more significant the improvement in anaerobic power. In our study, the cuff pressure used was between 90 and 120 mmHg, much lower than the cuff pressure used by Amani-Shalamzari in their research. Increasing the cuff pressure may have improved anaerobic power in participants in the SS-BFR group. Another possible reason is related to the low single-exercise dose of SS. In a different study, Amani-Shalamzari32 found that a single exercise dose of three minutes was effective when combined with small-sided games. By contrast, our intervention duration was just 30 s per session, which may have limited improvement in anaerobic power.

It has been demonstrated that BFR exerts several physiological effects, including the induction of cell swelling, premature recruitment of fast muscle fibers, and hormone secretion33,34. These effects, in turn, have been shown to increase anabolic stimulation of blood flow-restricted muscles. Our results revealed a significant difference between groups (p < 0.05) in the peak torque of the right leg extensors at 60 °/s. As observed in Amani-Shalamzari’s study31, combining BFR with running significantly increased the peak torque of the knee extensor muscles. We speculate that the significant improvement in peak torque of the right knee extensor muscles at 60°/s could be due to the reduced oxygen supply during BFR. This could have prompted the recruitment of extra motor units (type II muscle fibers) to compensate for the loss of strength35. Also, during SS, exercise-induced cell swelling and metabolic accumulation may intermittently stimulate anabolic hormonal changes36,37, which in turn stimulate group III and IV afferent nerves to increase fibre recruitment38, leading to an increase in muscle strength. Conversely, no significant differences between groups were observed for the remaining leg muscle strength indicators. SS itself can promote muscle strength gains. This is because Wun’s12 study found that even sporadic Wingate training can improve leg muscle strength. One possible explanation is the learning effect: participants may have developed a more efficient force generation pattern in the right extensor muscles during the 60°/s peak torque test, influencing the results. For these possibilities, it is, therefore, necessary to have a non-exercise control group that can be used to determine whether SS combined with BFR does indeed affect the changes in participants’ leg muscle strength, to determine whether they are affected by a learning effect or an improvement in muscle adaptation. It must be noted that sex differences may affect improvements in muscle strength. A particular study demonstrated that female subjects exhibited superior muscular endurance compared to their male counterparts during isometric knee extension training, both with and without the application of BFR39. A recent study revealed that, following a 6-week intervention involving low-intensity resistance exercise in conjunction with BFR, male subjects exhibited greater strength gains than female subjects40. Unfortunately, the effects of sex differences on muscle strength, as observed in this study, were not detected. Therefore, although this study observed a significant improvement in extensor strength, the results should still be interpreted with caution.

Similarly, in terms of sEMG, we did not observe any changes in the values of vastus medialis and vastus lateralis in either group of participants. In addition, a major limitation is that because SS is a multi-joint manoeuvre, the muscles involved are often not limited to vastus medialis and vastus lateralis, which limits our further understanding of the improvement in muscle status after SS (as adaptive improvements in muscles may also occur in the muscles around the ankle or hip joints) and is not conducive to observing whether SS is actually effective in improving muscle metrics (muscle activation, muscle fatigue). Although BFR combined with low-intensity exercise was observed to result in increased iEMG in a previous study41, no changes in vastus medialis and vastus lateralis were observed in either group of participants before and after the 6-week intervention, with or without the implementation of BFR. It is recommended that the overall movement of the lower limb muscles be monitored to further determine the effect of SS combined with BFR on muscle adaptation.

Limitations

First, the study involved a small sample size, which may have influenced the findings. Therefore, increasing the sample size in subsequent studies is recommended to strengthen the power of the observed results. Secondly, this study estimated cuff pressure by applying Loenneke’s20 prediction equation. While the original method employed a 5 cm cuff, our research utilized a 10 cm width, creating a specification discrepancy from the formula’s development parameters. This deviation could introduce systematic errors in AOP estimation. de Queiros‘42 studies have demonstrated that distinct key predictors arise when developing the equation for various cuff widths. For instance, in the case of a medium cuff width, thigh circumference serves as a predictor for lower limb AOP. In contrast, for a large cuff, SBP emerges as the primary indicator. Consequently, given the methodological inconsistencies in prediction, we do not advocate for the direct replication of this study without careful consideration of these variations. Using handheld Doppler probes43 and pulse oximeters44 may improve the rigour of BFR, as these methods have been validated in previous studies. Finally, the lack of a non-exercising (time-matched) control group limited our ability to distinguish the effects of BFR from natural adaptations induced by SS. Without a control group, we cannot exclude that the observed within-group SS-BFR improvements reflect general exercise benefits (e.g., neuromuscular coordination) rather than BFR-specific mechanisms. Future studies should include non-exercising cohorts to isolate the independent effects of BFR. Also, diet and lifestyle were not assessed. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that participants changed their physical activity and eating behavior throughout the study, which in turn may have affected body composition.

Conclussion

Although incorporating the current BFR parameters (40–50% AOP) into SS significantly increased the peak torque of the right leg extensor muscles at 60°/s, there were no additional effects on other indicators, such as body composition, sEMG, anaerobic power, and lower limb muscle strength. Further validation of the potential value of BFR in optimizing ES is recommended under more scientifically controlled conditions, such as pressure calibration, extending the intervention duration, and incorporating a non-exercise control group.

Data availability

Data provided in manuscripts or supplementary information documents.

References

Booth, F. W., Roberts, C. K. & Laye, M. J. Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Compr. Physiol. 2 (2), 1143–1211. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c110025 (2012).

Bull, F. C. et al. World health organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 54 (24), 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955 (2020).

Strain, T. et al. National, regional, and global trends in insufficient physical activity among adults from 2000 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 507 population-based surveys with 5·7 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 12 (8), e1232–e1243. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(24)00150-5 (2024).

Garcia, L. et al. Barriers and facilitators of domain-specific physical activity: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Public Health. 22,1964(2022).https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14385-1

Hupin, D. et al. Even a low-dose of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces mortality by 22% in adults aged ≥ 60 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 49, 1262–1267. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-094306 (2015).

Jakicic, J. M. et al. Association between bout duration of physical activity and health: systematic review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 51, 1213–1219. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001933 (2019).

Islam, H., Gibala, M. J. & Little, J. P. Exercise snacks: A novel strategy to improve cardiometabolic health. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 50 (1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1249/JES.0000000000000275 (2022).

Jenkins, E. M., Nairn, L. N., Skelly, L. E., Little, J. P. & Gibala, M. J.Do stair climbing exercise snacks improve cardiorespiratory fitness? Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme.44(6), 681–684 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2018-0675

Yin, M. et al. Exercise snacks are a time-efficient alternative to moderate-intensity continuous training for improving cardiorespiratory fitness but not maximal fat oxidation in inactive adults: a randomized controlled trial. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 49 (7), 920–932. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2023-0593 (2024).

Caldwell, H. G., Coombs, G. B., Rafiei, H., Ainslie, P. N. & Little, J. P. Hourly staircase sprinting exercise snacks improve femoral artery shear patterns but not flow-mediated dilation or cerebrovascular regulation: a pilot study. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 46 (5), 521–529. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0562 (2021).

Perkin, O. J., McGuigan, P. M. & Stokes, K. A. Exercise snacking to improve muscle function in healthy older adults: A pilot study. J. Aging Res. 7516939 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7516939 (2019).

Wun, C. H. et al. R.Efficacy of a Six-Week dispersed Wingate-Cycle training protocol on peak aerobic power, leg strength, insulin sensitivity, blood lipids and quality of life in healthy adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17 (13), 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134860 (2020).

Wong, P. Y. et al. A single all-out bout of 30-s sprint-cycle performed on 5 consecutive days per week over 6 weeks does not enhance cardiovascular fitness, maximal strength, and clinical health markers in physically active young adults. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 124, 1861–1874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-023-05411-0 (2024).

Zhou, J., Gao, X., Zhang, D., Jiang, C. & Yu W.Effects of breaking up prolonged sitting via exercise snacks intervention on the body composition and plasma metabolomics of sedentary obese adults: a randomized controlled trial. Endocr. J. 72 (2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1507/endocrj.EJ24-0377 (2025).

Yin, M. et al. Comment on exercise snacks and other forms of intermittent physical activity for improving health in adults and older adults: A scoping review of epidemiological, experimental and qualitative studies. Sports Med. 54, 2199–2203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-024-02080-7 (2024).

Patterson, S. D. et al. Blood flow restriction exercise: considerations of methodology, application, and safety. Front. Physiol. 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.00533 (2019).

Behringer, M., Behlau, D., Montag, J. C. K., McCourt, M. L. & Mester, J. Low-Intensity sprint training with blood flow restriction improves 100-m Dash. J. Strength. Cond Res. 31 (9), 2462–2472. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001746 (2017).

Amani-Shalamzari, S. et al. Occlusion training during specific futsal training improves aspects of physiological and physical performance. J. Sports Sci. Med. 19 (2), 374–382 (2020).

Fatela, P., Mendonca, G. V., Veloso, A. P., Avela, J. & Mil-Homens, P. Blood flow restriction alters motor unit behavior during resistance exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 40 (9), 555–562. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0888-8816 (2019).

Loenneke, J. P. et al. Blood flow restriction in the upper and lower limbs is predicted by limb circumference and systolic blood pressure. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 115 (2), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-014-3030-7 (2015).

Lunn, W. R., Zenoni, M. A., Crandall, I. H., Dress, A. E. & Berglund, M. L. Lower wingate test power outcomes from All-Out pretest pedaling Cadence compared with moderate Cadence. J. Strength. Cond Res. 29 (8), 2367–2373. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000216 (2015).

De Oliveira, M. P. B. et al. L. P. Reproducibility of isokinetic measures of the knee and ankle muscle strength in community-dwelling older adults without and with alzheimer’s disease. BMC Geriatr. 22 (1), 940. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03648-6 (2022).

Hermens, H. J., Freriks, B., Disselhorst-Klug, C. & Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 10 (5), 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1050-6411(00)00027-4 (2000).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences Hillsdale (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates,, 1988).

Herda, A. A. et al. Blood flow restriction during walking does not impact body composition or performance measures in highly trained runners. J. Funct. Morphology Kinesiol. 9 (2). https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk9020074 (2024).

Chang, H., Yang, X., Chen, B. & Zhang, J. Effects of different blood flow restriction training modes on body composition and maximal strength of untrained individuals. Life (Basel Switzerland). 14 (12), 1666. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14121666 (2024).

Hasan, R. et al. Can short bouts of exercise (Exercise Snacks) improve body composition in adolescents with type 1 diabetes?? A feasibility study. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 92 (4), 245–253. https://doi.org/10.1159/000505328 (2019).

Husmann, F., Mittlmeier, T., Bruhn, S., Zschorlich, V. & Behrens, M. Impact of blood flow restriction exercise on muscle fatigue development and recovery. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc. 50 (3), 436–446. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001475 (2018).

Fahs, C. A. et al. Muscular adaptations to fatiguing exercise with and without blood flow restriction. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging. 35 (3), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpf.12141 (2015).

Schwiete, C., Franz, A., Roth, C. & Behringer, M. Effects of resting vs. Continuous Blood-Flow Restriction-Training on strength, fatigue resistance, muscle thickness, and perceived discomfort. Front. Physiol. 12, 663665. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.663665 (2021).

Amani-Shalamzari, S. et al. B.Effects of blood flow restriction and exercise intensity on aerobic, anaerobic, and muscle strength adaptations in physically active collegiate women. Front. Physiol. 10, 810. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.00810 (2019).

Amani-Shalamzari, S. et al. Blood flow restriction during futsal training increases muscle activation and strength. Front. Physiol. 10, 614. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.00614 (2019).

Abe, T. et al. Effects of low-intensity walk training with restricted leg blood flow on muscle strength and aerobic capacity in older adults. J. Geriatric Phys. Therapy (2001). 33 (1), 34–40 (2010).

de Oliveira, M. F., Caputo, F., Corvino, R. B. & Denadai, B. S. Short-term low-intensity blood flow restricted interval training improves both aerobic fitness and muscle strength. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 26 (9), 1017–1025. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12540 (2016).

Loenneke, J. P. et al. Effects of cuff width on arterial occlusion: implications for blood flow restricted exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 112 (8), 2903–2912. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-011-2266-8 (2012).

Loenneke, J. P., Fahs, C. A., Rossow, L. M., Abe, T. & Bemben, M. G. The anabolic benefits of venous blood flow restriction training May be induced by muscle cell swelling. Med. Hypotheses. 78 (1), 151–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2011.10.014 (2012).

Jessee, M. B., Mattocks, K. T., Buckner, S. L., Dankel, S. J., Mouser, J. G., Abe, T., & Loenneke, J. P. (2018). Mechanisms of blood flow restriction: The new testament. Techniques in Orthopaedics, 33(2), 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1097/BTO.0000000000000252

Pope, Z. K., Willardson, J. M. & Schoenfeld, B. J. Exercise and blood flow restriction. J. Strength. Cond Res. 27 (10), 2914–2926 (2013).

Labarbera, K. E., Murphy, B. G., Laroche, D. P. & Cook, S. B. Sex differences in blood flow restricted isotonic knee extensions to fatigue. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 53 (4), 444–452 (2013).

Nancekievill, D., Seaman, K., Bouchard, D. R., Thomson, A. M. & Sénéchal, M. Impact of exercise with blood flow restriction on muscle hypertrophy and performance outcomes in men and women. PloS One. 20 (1), e0301164. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0301164 (2025).

Yasuda, T. et al. Effects of low-intensity, elastic band resistance exercise combined with blood flow restriction on muscle activation. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 24 (1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2012.01489.x (2014).

de Queiros, V. S. et al. Body position and cuff size influence lower limb arterial occlusion pressure and its predictors: implications for standardizing the pressure applied in training with blood flow restriction. Front. Physiol. 15, 1446963. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1446963 (2024).

Laurentino, G. C. et al. Validity of the handheld doppler to determine Lower-Limb blood flow restriction pressure for exercise protocols. J. Strength. Conditioning Res. 34 (9), 2693–2696. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002665 (2020).

Lima-Soares, F. et al. Determining the arterial occlusion pressure for blood flow restriction: pulse oximeter as a new method compared with a handheld doppler. J. Strength. Conditioning Res. 36 (4), 1120–1124. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003628 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. was responsible for identifying the research topic, designing the experimental protocol, and writing and revising the paper.M.L. was responsible for revising the paper and making suggestions.C.W. was responsible for compiling and analysing the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, J., Li, M. & Wang, C. Effects of blood flow restricted staircase sprint snacks on body composition, anaerobic power, and muscle strength in physically inactive students. Sci Rep 15, 26610 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11196-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11196-3