Abstract

Construction workers in Bangladesh experience disproportionate occupational health risks due to the lack of or inadequate safety measures. This study explores the on-site occupational health risks, the essential safety measures, and workers’ safety beliefs in Bangladesh’s construction industry. Following purposive sampling method, data were collected through forty in-depth interviews (IDIs) with workers and ten key informant interviews (KIIs) with contractors and building owners across nine construction sites, using a checklist and interview guidelines. The findings reveal that health risks vary by age and work experience, while formal safety training is virtually non-existent. Contractors typically provide substandard or insufficient personal protective equipment, and managerial oversight is limited due to weak supervision, disorganized worksites, and poor communication. Workers’ unsafe behaviors are primarily driven by low safety awareness, minimal education, and economic necessity. Safety beliefs, shaped by local work culture, peer influence, and individual confidence, contribute to risky behaviors and heightened health hazards. The findings align with Reason’s Accident Causation Theory and suggest an extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior to better capture localized safety perceptions. A context-specific framework is proposed to enhance occupational health and safety practices in Bangladesh’s construction industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background of the study

Globally construction sector is recognized as one of the most hazardous sectors that exposes workers to numerous health risks on building sites1. Construction is risky, often making the occupational environment unfavourable and inappropriate for the workers2. However, current literature identifies specific construction activities, such as the operation of machinery, concrete work, and channel construction, as particularly hazardous due to abrupt changes in work circumstances that frequently jeopardize worker health3. Consequently, construction workers encounter considerable risks to their occupational health and welfare4. Approximately 60,000 fatalities occur annually in the global construction industry, with over 720,000 workers injured daily5. Developed nations such as the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Hong Kong reflect this concerning trend6. The construction industry in India, the second-largest employer, is responsible for nearly one-fifth of all fatal occupational accidents worldwide7. The construction industry in Bangladesh, employing over 3.6 million people, is considered one of the most hazardous sectors8. In addition to accidents, Bangladeshi construction workers endure suffering from different types of illnesses due to low socioeconomic status, restricted access to healthcare, and inadequate health education9. Skin concerns are especially common among construction workers owing to the abrasive characteristics of concrete, a primary construction material10. Despite the intrinsic dangers of construction labour, occupational health concerns arise from both management authorities and the workers themselves11.

Prioritizing occupational safety is essential for protecting workers from health risks and improving project success because occupational health and safety (OHS) have a significant impact on employee productivity and organisational performance12. In Bangladesh, legal frameworks such as the Bangladesh Labor Act (BLA) 2006 (amended in 2018) and the Bangladesh National Building Code (BNBC) 2006 delineate rules for safeguarding workers’ health, safety, and welfare13. The Public Procurement Rules (PPR) (2008), governing government-funded projects in Bangladesh, ensure compliance with safety standards and regulations to guarantee worker safety14. Notwithstanding these laws, safety hazards on construction sites persist15. The state’s apathy toward the occupational safety of construction workers is apparent since the government has ratified only two relevant conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO)16. Moreover, inadequate understanding among management regarding competencies, risk assessments, safety protocols, and safety communication substantially undermines workplace safety17. Alongside administrative issues, a pivotal component affecting construction safety is the workers’ mindset18. The psychological engagement of employees in the safety protocol substantially influences workplace safety. The inclination of workers to prioritize task completion over safety concerns presents a substantial risk to occupational safety on construction sites19.

Many researchers have used the term “occupational health” to refer to long-term health issues or chronic illnesses20,21,22,23. This research employed the phrase to denote both long-term and short-term health concerns, including injuries, fatalities, skin illnesses, and other conditions that construction workers have endured or are presently experiencing. Moreover, “occupational safety” is a widely utilized term in the literature on OHS that refers to immediate safety hazards faced by workers, such as falls from heights and the use of slippery ladders, as well as other minor injuries23,24. This research applied the phrase “Safety Essentials” instead of “Occupational Safety” to refer to various factors such as safety training, construction management, safety communication, etc., which are crucial for reducing health risks and promoting OHS of the workers. This study also examined the “Safety Belief” of the construction workers which is conceptualized as the perception and judgment of the workers regarding the significance of following safety procedures in the workplace.

Current literature on OHS in Bangladesh predominantly centres on garment workers, specifically addressing occupational health and safety management systems (OHSMS) and worker performance25,26, threats to occupational health27, and various health difficulties28. The literature that addressed OHS issues in the construction industry is mostly concentrated on formally employed workers in government projects, ignoring those involved in informal personal projects nationwide, where contractors exclusively manage these projects, rarely prioritizing the application of safety essentials. Only a few studies on construction issues identified general safety practices and safety management29,30, without including all safety essentials and addressing the mental factors of the workers, such as workers’ attitudes and beliefs, that affect safety behaviour on construction sites. Their focus was primarily on examining the incidence of diseases and accident rates among workers while ignoring the firsthand experiences of workers that highlight the severity of the current situation. Consequently, this research sought to investigate workers’ direct encounters with health risks and managerial and behavioural factors. The researchers applied two dominant theories to take methodological help and interpret the data. The researchers also formulated a theory-driven framework to improve OHS conditions. This research thereby contributes to the attainment of relevant Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). Barbosa et al.31 and Fei et al.32 suggested that research on OHS of construction workers in developing nations is vital for achieving SDGs by mitigating occupational health hazards, enhancing workplace conditions, and safeguarding workers’ rights.

Theoretical framework

To understand the OHS of construction workers, the study has followed two dominant theories; Reason’s Accident Causation Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Reason’s theory explains the causal factors of the accident. Earlier, the role of the frontline workers was highlighted as the most evident instigator of the accident. However, Reason’s theory spans the entire accident sequence from organizational to individual levels33. The model divides failures into two; active and latent failures. Active failures are generally associated with the activities of workers that have an immediate adverse effect. Latent failures refer to mistakes at the management and decision-making levels34. Poor management culture as a latent failure creates an infinite number of unsafe behaviours that are often unpredictable. In addition, the lack of safety training originates from aberrant conditions in the construction industry35. The detrimental consequences of these failures give an unquenched space for health hazards to occur34.

TPB has been used by different scholars in conducting safety research in various fields to predict safety-related behaviour36. Ajzen developed TPB in 1995 which proposes that behaviour is determined by cognition (attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control), intention and behaviour framework37. Attitude refers to the importance ascribed for accomplishing an activity; subjective norm indicates social pressure to perform certain behaviour; perceived behavioural control refers to a prejudgment of the possibility of doing certain tasks38. Workers’ past experience, belief salience, morality, self-identity, and group identity together contribute to forming attitudes and subjective norms39. TPB postulates that the intention of workers to a particular work is determined by attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control. In performing any activity, favorability, expectation, and possibility are determined by these three factors of human behaviour40. The TPB also considers environmental influence in explaining human behaviour. According to this theory, safety interventions, such as safety training, PPE, etc., increase safety practices by improving the safety attitude of workers41.

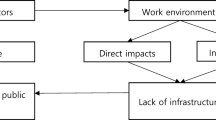

To guide the analysis of the study findings, a conceptual framework was developed (Fig. 1), drawing on TPB and Reason’s Accident Causation Theory. This integrated model seeks to explicate the interaction of behavioral, psychological, and organizational factors in shaping OHS practices among construction workers in Bangladesh. The framework conceptualizes management deficiencies—including the lack of safety training, inadequate supervision, poor communication, and the absence of personal protective equipment (PPE)—as latent failures, in line with Reason’s model. These deficiencies create a structurally unsafe environment, influencing workers’ intentions to undermine systematic safety practices. Incorporating TPB, the framework emphasizes on the centrality of workers individual psychological state that is shaped by three interrelated constructs; attitudes, which are informed by fatalistic beliefs and the perceived tension between safety adherence and productivity demands; subjective norms, shaped by hierarchical workplace relations and culturally embedded social expectations; and perceived behavioural control, which encompasses both actual control (e.g., access to safety resources, training, and managerial oversight) and perceived control (e.g., workers’ risk perception and safety self-efficacy). These components collectively inform workers’ commitment to engage in unsafe working practices. Unsafe behaviors are not simply the result of individual recklessness, rather, as Reason’s theory posits, they are the outcome of systemic vulnerabilities and organizational weaknesses, compounded by cultural and contextual factors in Bangladesh. The framework further delineates the consequential outcomes of these unsafe acts, which include increased workplace injuries, occupational diseases, and overall diminished safety performance. While TPB is valuable for understanding individual decision-making, it is not adequate for explaining the sociocultural and hierarchical complexities of the construction sector in Bangladesh. In this context, like many countries in Global South, construction workers’ behavior is not solely shaped by psychological factors but is deeply influenced by cultural values, conformity to group norms, and respect for authority figures. The collectivist cultural expectations often create strong social pressures that override personal risk assessments. Moreover, workers fully remain submissive to contractors due to fear of job loss. This situation compels workers to engage in unsafe practices despite awareness of potential risks.

Objectives of the study

The general objective of the study is to understand the OHS of the construction workers in Bangladesh. However, to gain a comprehensive understanding of the OHS of construction workers on current sites in Bangladesh, this study specifically pursued the following objectives:

-

To explore the occupational health risks that construction workers face on construction sites in Bangladesh;

-

To investigate the factors that are essential for the occupational safety of construction workers in Bangladesh; and.

-

To understand construction workers’ beliefs regarding their health and safety at work.

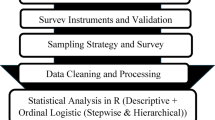

Materials and methods

Study area and respondents

The study followed a qualitative research design which is primarily used to enhance knowledge of the topic that needs to be known better42,43. This research was carried out in the Sylhet City Corporation area since construction-related research in Bangladesh has been conducted predominantly covering the capital city, Dhaka, due to its rapid urbanization and high construction activity44,45,46,47. To bridge the gap between the capital city and other areas, the researchers deliberately selected this region. The Sylhet City Corporation area is 79.50 sq. km with a population of approximately 1 million across 42 wards48. During fieldwork, many building projects were found underway in various Wards of the City Corporation area. However, the building authorities restricted access to several building sites. Initially, the study included participants from six sites in four Wards. Then, based on the scholarly suggestions of five qualitative research experts, the researchers included three sites from two additional Wards to strengthen the study results and enhance the overall argument. Table 1 provides information about the sample area along with respondents’ numbers.

Purposive sampling was used to obtain data from respondents since it is a means of selecting a sample based on the judgment of the researcher. Workers having at least 2 years of experience in this sector were included in this study anticipating that experienced workers would have a deeper understanding of health risks and safety issues than the fresh workers. This strategy facilitates the researchers to explore a comprehensive view of the OHS of construction workers in Bangladesh. A total of 71 workers were identified to be eligible for participation; however, 50 workers consisting of both males and females participated. The researchers also invited all contractors and building owners of the selected sites to participate as key informants, but only 6 contractors and four building owners gave consent for participation. Table 2 provides the key demographic information of all respondents who participated in this study.

Data collection techniques and tools

The researchers conducted IDIs with construction workers and KIIs with contractors and building owners to collect data. A checklist and two sets of interview guidelines—one tailored for contractors and another for building owners—were designed in alignment with the theoretical framework illustrated in Fig. 1. During preparing the checklist, issues were included being guided by the theoretical framework. For example, several questions were asked to know management deficiencies including “Are you pressured by your contractor to work longer hours or perform more tasks?”, “Why do you not use helmets and gloves at work?”, “Have you ever received any safety training for your work?” and “Does your contractor instruct you before starting any risky tasks?” To explore the enforcement of safety measures, questions like “Are PPEs provided to you?” and “Does your contractor monitor your work?” were included. To explore the psychosocial factors, a few questions were included like, “What do you personally believe about the importance of safety in your work?”, “How do you consider PPE for your safety?”, “Why do you not follow safety practices at work?” and “How do workers typically react when someone experiences an accident?” To understand fallible decision-making and behavioural intentions, questions such as “What kinds of work do you complete using shortcuts, and why?”, “How often do you work in risky conditions?” and “Do you anticipate the risks before starting hazardous tasks?” were included. Prevalence and nature of health-related risks were reflected in the questions, like, “Have you experienced or witnessed any injuries at site?”, “How often do accidents occur at your workplace?” and “How did you manage while experiencing injuries?”

Similarly, interview guidelines included the questions, such as “Why do you not arrange safety training or awareness programs for workers?”, “How do you communicate with workers?” and “Why do you remain absent at site?”, that revealed management-level deficiencies. To assess perceptions of workers’ attitudes toward safety, questions like “How would you describe workers’ attitudes toward safety on-site?”, “What do you think are the reasons workers are not genuinely committed to safe work practices?” and “How do you address workers’ neglect of safety protocols?” were incorporated. The question “What safety measures do you take to ensure worker safety?” was used to examine existing defence mechanisms. To understand risk behaviours and health-related hazards “What safety risks have you observed on-site?” was asked.

The first author prepared the tools in consultation with the second and third authors. Subsequently, the first author conducted interviews with three workers and one contractor to assess the tools’ effectiveness in eliciting appropriate responses from participants. The first author then shared these findings with the second author, who emphasized the need to address cultural and contextual issues. The refinement and revision of the tools were made based on the second author’s feedback. Data collection was accomplished solely by the first author with the assistance of a data collector. The first author asked the respondents and the data collector wrote the responses of the participants besides recording the interviews. Interviews with workers lasted between 30 and 45 minutes and the length was 60 minutes with contractors on average. However, the building owners were interviewed longer time than both contractors and workers. During fieldwork, the researchers conducted both IDIs and KIIs with those who showed willingness to participate in the study. Female respondents did not feel comfortable being interviewed at work, so they were interviewed at home. Since male workers were staying in makeshift tents built on-sites, they were interviewed in their tents during off time.

Data analysis

In addition to taking written notes during the interviews, all sessions were audio-recorded using a mobile phone. Upon completion of each interview, the recordings were transcribed by the interviewer. To ensure accuracy and evidence-based analysis, the transcribed data were cross-checked with field notes. The inductive analytical approach was primarily adopted being guided by the theoretical model of this study. Themes were generated after careful reading of verbatims making alignment with the theoretical constructs used in this study. In the analysis of health-related risks, abstractions from the participants’ narratives were highlighted. While examining participants’ statements regarding occupational safety and workers’ safety beliefs, deeper insights and structural factors were uncovered. The study employed Braun and Clarke’s49 six-phase framework for thematic analysis, which provided a systematic and rigorous approach. First, the researchers engaged in repeated reading of the transcripts to become familiar with the data. Second, initial codes were generated, focusing on concepts relevant to TPB and accident causation theories. Third, related codes were grouped to construct preliminary themes, with careful attention paid to identifying patterned meanings. Fourth, these themes were reviewed and refined to ensure alignment with the research objectives and theoretical underpinnings. Fifth, clear and meaningful headings were assigned to each theme. Finally, the confirmed themes were used to structure the findings of the manuscript.

Initial coding was made by reading line-by-line to capture descriptive and interpretive insights. These initial codes were then organized into conceptual groupings such as “types of occupational health risks,” “types of occupational health diseases”, “organization of work”, etc. Through iterative discussions within the research team, these grouped codes were further refined into analytically coherent themes, including Understanding Health Risks, Critical Factors of Safety, Construction Workers’ Safety Beliefs. This analytical process is illustrated in Table 3, which demonstrates the pathway from raw data to final thematic categorization. Thematic saturation was reached when no new themes emerged from ongoing data collection. While initial coding commenced after the first 10 interviews, by the 40th interview, the data began to repeat existing patterns without contributing substantially new insights. Nevertheless, all 50 IDIs and KIIs were included in the final analysis to capture the diversity and richness of participants’ experiences. Researchers’ reflexivity was maintained throughout the study. The first author, who conducted all interviews and led the coding process, brought prior academic and contextual familiarity with occupational health issues in the Bangladeshi construction sector. To strengthen analytical reliability, the second and third authors, who were not involved in data collection, independently reviewed the codes and thematic framework. Their critical input, combined with several rounds of discussion and refinement, ensured that the themes were conceptually sound, empirically grounded, and not unduly influenced by the first author’s positionality.

Verbatims were selected to accurately express the sentiments, experiences, and latent meanings of the narratives50. This thematic analysis was appropriate for the study context, enabling a theory-driven analysis that both explicated the underlying ideas in participants’ narratives and depicted a picture of ground-level realities of OHS experienced by construction workers in Bangladesh. The third author guided the selection of appropriate verbatims from respondents’ narratives to increase the readability of the identified themes.

Research ethics

The study was conducted following the ethical guidelines of the Research Center of Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh. The study was conducted as part of a Master’s thesis, completed over three semesters. The research protocol, including the study design, data collection instruments, data analysis, and ethical considerations, was reviewed and approved by the respective institutional review committees at multiple stages of the timeframe. In the first semester, the first author developed the research proposal, which was formally presented before a review committee and it approved the proposal. In the second semester, the author conducted an extensive literature review, identified the research gap, and developed research instruments. These were also reviewed and approved through departmental procedures. In the final semester, the first author collected and analysed the data, prepared the thesis report, and successfully presented the findings in front of scholars. Each phase of the work was rigorously evaluated by the supervisor and respective institutional committees. Informed consent was taken from the participants as it provided an extended opportunity to ask questions51. It was taken verbally from respondents because many were illiterate and fearful of giving written consent. Data collection tools were pretested and reviewed to avoid questions that could create conflicts or hurt anyone of the respondents. Voluntary participation of respondents was ensured. They have been given the opportunity to quit the interview anytime they wish. They were given assurance of maintaining the confidentiality of their information. The anonymity of the respondents has been maintained.

Limitations of the study

The study, conducted using a qualitative methodology, has limitations. The findings, based on narratives of the workers from a specific region, may not be generalized across the entire country. The unequal participation of male and female workers could affect the robustness of the findings. Future research should employ a more extensive and representative sample size, including various worker segments, and utilize advanced statistical analyses to produce more valid and reliable results. Additionally, future research could delve into the impact of safety beliefs on safety practices to propose robust recommendations for ensuring the safety of construction workers.

Results of the study

Results have been presented in three sections; understanding health risks, critical factors of health safety, and construction workers’ safety beliefs.

Understanding health risks

This study finds various occupational injuries and diseases among workers that are shown in the Table 4 with extracts from the statements of the respondents of this study.

Critical factors of health safety

Occupational health safety in the construction sector is profoundly impacted by safety training, safety education, PPE, contractors’ supervision, organization of the work, and contractors’ communication with workers. These factors are described in the following.

Safety training

It is essential to provide safety training to enhance workers’ skills and ensure safety at work. However, the construction industry lacks a fundamental understanding of occupational safety. Workers highly value safety training for its role in enhancing workplace efficiency and ensuring safety. However, some contractors prioritize hiring experienced labourers over investing in safety training. This practice frequently results in increasing the chances of workplace injuries. One respondent recounted a personal incident:

I was assigned a task of cutting rods using a machine, which I had never performed before. I connected the machine by plugging it into an electric socket, and after some time, the wire was unexpectedly pulled, causing the machine to spark, which resulted in eye irritation.

While inexperienced workers are more susceptible to workplace accidents and injuries due to unfamiliarity and lack of skills, experienced workers may face risks due to self-complacency or overconfidence. An experienced worker shared:

A co-worker with nearly a decade of experience in construction was quickly laying bricks on a wall. After building a wall about two feet high, the entire structure collapsed, causing a serious injury to his leg. He has been absent from work for several days due to this injury.

Inadequately secured formwork, which supports concrete during construction, or incorrect masonry techniques can not only cause delays but also greatly increase the chances of injuries. Furthermore, untrained or inadequately trained workers often lack fundamental understanding of masonry techniques, which not only causes construction delays but also disrupts the workflow. Another worker described the challenges of transitioning to a new role on an unfamiliar construction site:

As a newcomer to this site with no prior urban construction experience, I faced many difficulties adapting to the work environment. Previously, I assisted in carrying concrete. Due to lack of fundamental knowledge about concrete mixture ratios, initially I was puzzled and made errors in mixing.

This example highlights the potential outcomes of insufficient construction training, which not only puts the stability of buildings at risk but also endangers the long-term health and safety of construction workers.

Safety education

Construction workers generally lack formal education and receive no training on occupational safety, leaving them largely unaware of health risks and best practices for on-site safety. One employer noted that:

The absence of formal safety training renders workers unaware of essential health protections. This deficiency also reduces their motivation to adhere to safety protocols on site.

In this sector, employment practices worsen these issues as contractors informally hire workers without considering their educational backgrounds or prior safety training. New hires are rarely provided with job-specific training or safety awareness initiatives. An experienced labourer explained:

Contractors often employ new workers based on verbal agreements, permitting them to start work immediately without any preliminary safety orientation. These workers begin with limited or no understanding of how to protect their health on-site, as contractors prioritize physical readiness over safety knowledge. This lack of attention results in a higher risk of injuries and accidents.

It is clear that workers need safety awareness as it greatly impacts their compliance with construction protocols and helps reduce exposure to hazardous conditions. As another worker expressed:

Building safety awareness among us is crucial; it encourages adherence to safe work procedures and reduces suffering from various adverse situations.

Senior workers recognize that the absence of safety education and awareness directly leads to unsafe practices and OHS difficulties. Reflecting on this, one labourer shared:

Construction work is inherently risky and requires constant vigilance. However, many of us only grasp this after experiencing injuries. This occurs largely because most workers have little or no formal education, making them unaware of workplace health and safety.

Occasionally, informal discussions between contractors and workers address job expectations, but these rarely cover safety considerations. A worker recounted as follows:

The contractor instructed us to expedite the work but did not mention anything about safeguarding ourselves from injuries or accidents. We are compelled to prioritize survival over safety. Raising safety concerns can lead to termination, so we cannot focus on avoiding hazardous situations.

Owners agree that workers are being inattentive and facing increased risk because of the lack of safety education and awareness.

Personal protective equipment (PPE)

PPE is crucial for safeguarding construction workers from various health hazards. Training on PPE usage is essential to improve worker safety compliance, as one building owner noted:

Educating workers on the importance and correct application of PPE would increase their willingness to use it and enhance workplace safety standards.

However, the supply of PPE is largely dependent on the discretion of individual contractors in Bangladesh.

Contractors provide PPE only for specific high-risk tasks. However, contractors blame workers for not using PPE. One contractor mentioned,

I supplied helmets, gloves, and boots for workers during casting work on a building roof, but workers are unwilling to use PPE Some workers found the gloves uncomfortable, making their hands feel heavier and limiting finger movement.

Echoing the above statement another contractor shared:

Workers are reluctant to use helmet because it restricts the easy mobility of head, slowing down their work.

These statements highlight the workers’ lack of safety awareness, resulting in risky behaviors and a reluctance to use PPE. Workers do not agree with contractors. Confronting contractor statement, a worker noted that contractors’ frequent harsh behaviors and pressure lead them to complete tasks quickly, which discourages adherence to safety measures, like using PPE.

Contractors’ supervision

Expert supervision is crucial in preventing errors and ensuring operational accuracy in construction work. Contractors can offer immediate on-site supervision, giving direct guidance to workers. They manage several construction projects concurrently which limits their ability to comprehensively monitor every location. As a result, they prioritize their visits according to each site’s progress. One worker explained:

Our contractor is currently managing four sites. He visits our site every two days to oversee the progress. Recently, he has been visiting another site daily, where roof casting for a multi-story building is underway.

Another worker echoed a similar experience:

Our contractor primarily visits the site to check task completion rather than to offer on-the-job supervision. He stays in contact with senior workers via phone, providing remote instructions to guide them.

Each construction site poses unique safety risks. Continuous on-site supervision is vital for enforcing safety protocols and fostering worker alertness and caution during work hours. However, it is surprising that supervisors are rarely concerned about health and safety issues. A worker shared that:

Contractors sometimes pass idle time or engage in casual conversations rather than actively monitoring ongoing tasks to identify potential hazards.

Organization of the work

Maintaining an ordered workflow is essential for efficiency, safety, and cost-effectiveness. Despite the necessity, disorganized conditions at the workplace expose heightened safety risks. The lack of prioritization in task management not only causes delays in project implementation but also increases safety risks and financial losses for construction projects. A worker narrated his experience:

I was assigned to work on the staircase frame using metal rods which required a larger team with tools. Nearby, some masons were plastering, some were laying bricks on the basement wall who were assisting me in the beginning. When they returned to their respective tasks, I was bending a rod to form the staircase frame alone and got injured my hand at the hinge. It could not be happened if they were with me.

Contractors’ communication with workers

Effective communication between contractors and workers is essential for maintaining work momentum and fostering dynamic teamwork. However, during visits to the research sites, effective communication between contractors and workers with clear and purposeful message was found missing . Insufficient safety communication often leads to work-related injuries. One worker shared his experience:

I was instructed to switch off the grinder machine, but the switchboard was in a separate room. When I entered, my foot accidentally touched a faulty electrical line, and I nearly experienced electrocution.

This incident demonstrates how workers become vulnerable if they do not receive sufficient instructions. Workers, particularly subcontracting and substitute, often bear a high risk for lack of experience and minimal interaction. One worker noted:

Substitute workers tend to be reserved and often work without much interaction with the team and are more likely to experience accidents and workplace hazards.

Though contractors placed importance on safety communication, workers expressed deep concern for delayed or dismissive responses and the threat of job termination. Interpersonal communication between workers is crucial for identifying and mitigating safety risks in the construction environment. One building owner emphasized:

Communication between workers and -contractors are equally essential because it allows transfer of knowledge to encounter unwanted workplace hazards. It also prevents repeated mistakes, creates a supportive environment, and enhances the competency of workers.

Construction workers’ safety beliefs

Ensuring workplace safety at the construction sites is a multifaceted challenge. It is very often exacerbated by local workplace cultures that impede adherence to essential safety protocols. Contractors, who are primarily responsible for improving safety performance, often ignore safety regulations and do not provide any safety training. Workers are relied on informal practices as contractors provide makeshift safety measures. One building owner recounted the following:

I have witnessed a fragile state of workplace safety due to inadequate PPE. Contractors offer sandals for walking on uneven surfaces and debris, along with hats for protection from the sun or head injuries. I have also noticed workers placing folded handkerchiefs or similar items on their heads to provide support when lifting heavy loads. Contractors often supply rope ladders for workers to get access to the upper floors of buildings. While these measures are meant to be protective, they increase the risk of accidents.

Interestingly, workers show little concern about these inadequate precautions. In the study area, workers often perceive safety protocols as obstructive to fulfilling their target set by the contractors even though head injuries are a potential risk on the construction site. This decision may create a more comfortable work environment and help workers meet contractor-set deadlines. Additionally, the informal sharing of task methods among workers, along with their individual interpretations of task execution, often fosters negative attitudes toward following safety protocols, further exacerbating risks. One building owner shared the following incident:

Once two workers attempted to lift a heavy machine from the ground floor to the second floor. I suggested them to involve more workers, but other workers engaged nearby refused considering it as an easy task. Ironically two workers later complained about pain and stiffness in their lower backs.

This situation highlights the lack of managerial initiatives such as adequate supervision and communication, which leads workers to foster a poor safety belief. Moreover, workers’ reluctance to engage in safety practices is often fueled by their belief that workplace injuries and fatalities are inevitable. It resonates with the safety precautions at construction sites. The study also identified a tendency among workers to prioritize speed over safety, increasing the likelihood of accidents. One respondent recounted:

A fellow worker was cutting rods for a roof casting frame. Since many rods needed to be cut, he used an electric hacksaw to cut several rods at once, creating erratic sparks that caused eye irritation.

The influence of pressure from contractors or senior workers frequently compels junior employees to undertake precarious tasks. One worker shared his experience:

I was pressured to operate a vibrator machine to ensure proper mortar integration during casting, despite having no prior experience with the task. When I started operating the machine, it became stuck in the casting frame, and I strained my hinge.

Internal conflict among workers restrains them from making a consensus on safety issues and limits their collective voices. If senior workers impose something on junior workers that they are unwilling to do, it creates mistrust and conflict between them which in turn weaken their collective voices. In the absence of collective voices, they cannot place any demands for increasing their safety and security. Furthermore, constant fear of accidents may increase the safety risk. Like many others, one worker said:

We cannot anticipate the risks for lack of experience and proper guidance. when we decide to start a risky job, we continuously feel threat. It may often create insecurity and excessive fear which in turn increase the risk of injury.

Discussion

This research was conducted to investigate the OHS of the construction workers in Sylhet, Bangladesh. The findings of the study reveal that young construction workers commonly experience pain in the back and muscle discomfort, cuts on hands and legs, scratches on the skin, and suffer from issues with eyes and skin diseases. Workers’ experiences of health hazards vary based on physical capacity, work experience, risk exposure, and adaptability to the working environment. Older workers are often more experienced and skilled, but they are physically less resilient. Although their experiences and skills help them avoid certain common injuries, age-related vulnerabilities make them susceptible to respiratory issues and musculoskeletal problems52,53. Aged workers face injuries to knees, ankles, and other joints, and respiratory problems. A similar finding was reported in the study of Tetik et al.54, which mentioned higher rates of serious or fatal injuries among workers aged over 35 years old. Younger workers, on the other hand, are physically strong, but their fewer working experiences make them more exposed to those mentioned health risks. Earlier research indicates that industries that are labour-intensive face occupational hazards, but the construction industry is generally more hazardous due to the nature of the work30. Health risks in the construction industry vary across different regions of Bangladesh. In Dhaka city, construction workers commonly experience contact dermatitis, although they bear a significant burden of other skin diseases, including fungal infection, scabies, and acne9. Hasan et al.55 reported respiratory problems, back pain, and other related injuries as the major health hazards in Patuakhali, a district of Bangladesh. The regional differences in occupational health risks in the construction industry across Bangladesh likely stem from varying levels of worksite conditions, safety practices, PPEs, and weather patterns. Handling concrete, such as sand, cement, and stone, using construction equipment and an unsafe working environment largely contribute to these health risks10. Similar to the context-specific risks identified in Turkish historical building sites, such as unstable structures and exposure to hazardous materials56, this study also reveals unique environmental hazards in urban areas of Sylhet district. Construction projects being implemented on waterlogged or waste disposal places expose workers to a heightened risk of skin diseases. This emphasizes the need for localized occupational safety planning for addressing site-specific health risks.

Furthermore, this research identified safety training, safety education, contractors’ supervision, PPE, organizing construction projects, and contractors’ communication with workers as essential for ensuring occupational safety. However, regarding safety essentials, different reactions among stakeholders were observed. While contractors emphasize profit maximization by completing projects within tight deadlines, usually at the cost of labour safety, workers often hesitate to speak out owing to fear of job loss. Nonetheless, building owners stress the need to reduce health hazards by applying safety measures. They impose responsibilities on contractors to ensure a safe working environment by providing proper training and supervision to workers. Although safety measures are important, contractors of self-managed projects have not followed any policies to apply them, leading to increased risks for workers. These findings expose management flaws that are compatible with the management deficiencies explained by Reason’s theory. Although contractors sometimes arrange informal discussion meetings with workers, they ignore the skill development and safety-related issues of the workers. A recent study by Chan et al.57 highlighted the need for improved safety training in developing countries. As workers lack safety education, they remain unaware of their OHS at work. Likewise, workers lack basic construction knowledge, which includes understanding the ratios of concrete materials needed to prepare construction mortar. As they have poor safety knowledge, they cannot raise their voice against the existing work culture58. A noteworthy finding of this study is the shared perception among both contractors and workers that the use of PPE is problematic, reflecting an active failure as conceptualized in Reason’s theory. While contractors occasionally provide PPE, it is often inadequate or inappropriate for ensuring meaningful protection for workers. This aligns with the findings of Akboğa-Kale and Eskisar59, who observed that a significant proportion of unsafe acts on construction sites stem from the failure to supply workers with proper equipment. The use of PPE is influenced by previous accident experiences, safety awareness, perceived effectiveness of PPE, and the conditions of the workplace60. In the current study, building owners attribute the reluctance of workers to use PPE to a lack of education and awareness and emphasize that contractors should initiate simulation training to ease its use. Despite the crucial role of supervisory support in enhancing workers’ safety performance61, Bangladeshi workers frequently experience inadequate supervision from contractors, reflecting a perceived lack of seriousness in ensuring worker safety. Irregular communication between contractors and workers often hampers project organization, leaving workers uninformed about health risks that jeopardizes their safety. Tight work schedules further worsen the situations and increase the likelihood of accidents. In developing countries, construction management shows low levels of management practices62,63. Conversely, in developed countries, construction management is characterized by higher maturity levels in project management practices, often supported by established legal frameworks, robust infrastructure, skilled labour, and advanced technologies64.

However, the injuries and accidents in this industry often result from workers’ failure to follow proper procedures65, compounded by pressure from foremen and safety officers66. Furthermore, local working contexts play a crucial role in occupational safety, shaping negative safety beliefs among workers, which are further reinforced by the absence of training, supervision, monitoring, and communication. Worker group interactions, peer networks, and self-confidence are significant factors in determining the safety beliefs of workers. These findings are consistent with the study by Shabani et al.66, which investigated the impact of behaviour-based procedures on workplace safety. This safety belief system is shaped in a way that leads workers to undermine their OHS at work. It adversely impacts the workers by instilling a sense of desperation in them. Interestingly, safety beliefs differ between male and female workers, as female workers hold positive safety beliefs and exhibit a more cautious approach towards work. Another important finding is that senior workers exhibit self-serving behaviour towards junior workers, abstaining from risky work and delegating responsibility to junior workers who lack prior experience in such tasks. This result suggests that safety beliefs among male workers improve with age as they gain more experience at work. Furthermore, contractors often exhibit demanding behaviour towards workers in an attempt to extract more labour from them and expedite the completion of the project in order to save more money. Although these patterns of behaviour may ensure the safety of some older workers and increase financial benefits for the contractors, they must establish a long-lasting system that prevents a significant portion of workers, particularly those who are new or have limited experience, from paying attention to OHS, using personal PPE, and adhering to other safety measures. While the majority of the findings regarding safety beliefs align with the TPB, there exists a gap between theoretical propositions and the realities of different local working contexts. This study employs the TPB36 and Reason’s Accident Causation Model33 to examine occupational health risks in the Bangladeshi construction sector. While these frameworks offer foundational perspectives on behavioral intention and systemic failure, the empirical findings from this study reveal contextual complexities that call for significant adaptations. In particular, the local work culture, informal hierarchies, and structural inadequacies demand a nuanced extension of these theoretical models. In terms of attitude, the data reveal widespread fatalistic beliefs among workers, such as the conviction that accidents are inevitable, alongside a perception that safety protocols hinder productivity. These culturally embedded beliefs undermine the rational choice assumptions of TPB and suggest that the attitude construct should be expanded to account for fatalism and the productivity-safety trade-offs commonly accepted by workers. The findings show that junior workers are frequently compelled by senior colleagues to engage in high-risk tasks, and that managerial attitudes prioritize output over safety. These dynamics reflect a system of hierarchical coercion and informal authority that operates beyond the neutral social influence assumed by TPB. Therefore, subjective norms in this setting are shaped by power imbalances and internalized organizational neglect, rather than collective behavioral standards. Workers have the lack of safety knowledge and resources that often motivate them to work in unsafe condition. In response to these insights, this study proposes a theoretical adaptation of TPB to comprehensively capture worker behaviour and safety practices in a country like Bangladesh.

Policy implications

This study provides practical insights for cutting off occupational health risks by employing safety essentials in the construction sector in Bangladesh. The results explored management deficiencies, which suggest the necessity for management personnel to comprehend and address the underlying causes of health risks occurrences on-sites. Furthermore, the results regarding the negative safety beliefs of workers underscore the significance of addressing the psychological factors of workers. This study advocates for implementing worker-centric approach that are required to bring a positive change in workers’ belief systems to equally prioritize both health safety and workplace commitment. Special focus on regulatory and policy development is essential to bring the construction industry under strict regulation. The adapted framework (Fig. 2) informs a series of initiatives essential for improving the OHS of the construction workers in Bangladesh. The framework aligns with existing national institutions and policy instruments. For example, initiatives such as leadership accountability, root cause analysis, and feedback loops can be implemented through the Ministry of Labour and Employment and Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments (DIFE). These components can also be integrated into site-level monitoring systems under the Bangladesh National Building Code (BNBC). Environmental enhancement strategies, including risk control through engineering modifications, PPE provision, and equipment maintenance, can be enforced via BNBC and monitored by the Local Government Engineering Department (LGED). Furthermore, the Public Procurement Rules (PPR) 2008 could be revised to reward contractors who implement advanced safety practices and technology. Regulatory enforcement should also be strengthened by fully operationalizing the Labour Act 2006 (amended in 2018), ensuring stakeholder compliance across formal and informal sectors. At the worker level, behavioral training can be incorporated into the Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) curriculum under the Bangladesh Technical Education Board (BTEB), equipping future construction workers with essential OHS competencies. Peer-support networks and participatory approaches can be supported by NGOs like Bangladesh Occupational Safety, Health, and Environment (OSHE) Foundation and labor rights organizations such as the Bangladesh Institute of Labour Studies (BILS). Training modules should be delivered through institutions like the Bangladesh Industrial Technical Assistance Center (BITAC), and pilot initiatives can be embedded within municipal construction projects. Finally, inter-agency coordination through policy dialogues led by the above-mentioned bodies are essential to mainstream the framework into national practice.

Conclusion

Although construction work is characteristically accompanied by different diseases and fatalities, risk at work is largely created by managerial failures, workers’ unsafe behaviours, and poor safety beliefs in Bangladesh. Lack of safety training, poor site management, inadequate contractors’ supervision, poor project organization, and irregular safety communication between contractors and workers signify the latent failures of Reason’s theory that are responsible for poor OHS in the construction sector to a large extent. Construction workers hold poor safety beliefs being influenced by defiance, intent, group interactions and their self-confidence, which are in line with active failures of Reason’s theory and support the expectations of TPB theory. However, worker psychology and behaviour are also influenced by some additional factors that should be incorporated into TPB theory to provide full coverage to differential local and regional contexts. Finally, while workers of different regions are continuously experiencing various occupational health risks, immediate and urgent interventions are required to guarantee the OHS of workers and improve the workplace environment applying safety essentials that are currently fully or partially absent in the construction industry in Bangladesh. Therefore, if proper policy and practical initiatives are not in place, occupational health problems and safety threats will continue to be the major challenges for the construction industries in Bangladesh in the future.

Data availability

The authors confirm that all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

References

Sousa, V., Almeida, N. M. & Dias, L. A. Risk-based management of occupational safety and health in the construction industry—Part 1: background knowledge. Saf. Sci. 66, 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2014.02.008 (2014).

Sultana, N., Ferdousi, J. & Shahidullah, M. Health problems among women building construction workers. J. Bangladesh Soc. Physiol. 9, 31–36. https://doi.org/10.3329/jbsp.v9i1.22793 (2014).

Lee, L. J. H., Lin, C. K., Hung, M. C. & Wang, J. D. Impact of work-related cancers in Taiwan—estimation with QALY (quality-adjusted life year) and healthcare costs. Prev. Med. Rep. 4, 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.05.015 (2016).

Dutta, M. J. Migration and health in the construction industry: culturally centering voices of Bangladeshi workers in Singapore. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 14, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14020132 (2017).

Patel, D. A. & Jha, K. N. An estimate of fatal accidents in Indian construction. In Proc. 32nd Annu. ARCOM Conf. 539–548Association of Researchers in Construction Management, (2016).

Pandit, B., Albert, A., Patil, Y. & Al-Bayati, A. J. Fostering safety communication among construction workers: role of safety climate and crew-level cohesion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16010071 (2019).

Kanchana, S., Sivaprakash, P. & Joseph, S. Studies on labour safety in construction sites. Sci. World J. 2015 (590810). https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/590810 (2015).

Ahmed, S. Causes and effects of accident at construction site: a study for the construction industry in Bangladesh. Int. J. Sustainable Constr. Eng. Technol. 10, 18–40. https://penerbit.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/IJSCET/article/view/4499 (2020).

Bhuiyan, M. S. I., Sikder, M. S., Wadud, F., Ahmed, S. & Faruq, M. O. Pattern of occupational skin diseases among construction workers in Dhaka City. Bangladesh Med. J. 44, 11–15. https://doi.org/10.3329/bmj.v44i1.26338 (2015).

Lette, A., Ambelu, A., Getahun, T. & Mekonen, S. A survey of work-related injuries among building construction workers in Southwestern Ethiopia. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 68, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2018.06.010 (2018).

Reason, J. Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents (Routledge, 2016). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315543543

Shabani, T., Jerie, S. & Shabani, T. The impact of occupational safety and health programs on employee productivity and organisational performance in Zimbabwe. Saf. Extreme Environ. 5, 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42797-023-00083-7 (2023a).

Ansary, M. A. & Barua, U. Workplace safety compliance of RMG industry in bangladesh: structural assessment of RMG factory buildings. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 14, 424–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.09.008 (2015).

Hossain, M. K. & Islam, M. Z. Good governance practices in procurement operations and quality procurement: a comparative study between public and private sector organisations in Bangladesh. Int. J. Procure. Manag. 14, 796–820. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPM.2021.117890 (2021).

Hossain, M. M. & Ahmed, S. A case study on safety assessment of construction project in Bangladesh. J. Constr. Eng. Manag Innov. 1, 147–156. https://doi.org/10.31462/jcemi.2018.04147156 (2018).

Bhuiyan, A. J. & Haq, M. N. Improving occupational safety and health in Bangladesh. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health. 14, 231–233. https://doi.org/10.1179/oeh.2008.14.3.231 (2008).

Teo, E. A. L., Ling, F. Y. Y. & Ong, D. S. Y. Fostering safe work behaviour in workers at construction sites. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 12, 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1108/09699980510608848 (2005).

Mohammadi, A., Tavakolan, M. & Khosravi, Y. Factors influencing safety performance on construction projects: a review. Saf. Sci. 109, 382–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2018.06.017 (2018).

Wu, X., Liu, Q., Zhang, L., Skibniewski, M. J. & Wang, Y. Prospective safety performance evaluation on construction sites. Accid. Anal. Prev. 78, 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2015.02.003 (2015).

Harrison, J. & Dawson, L. Occupational health: meeting the challenges of the next 20 years. Saf. Health Work. 7 (2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2015.12.004 (2016).

Rushton, L. The global burden of occupational disease. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 4, 340–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-017-0151-2 (2017).

Bira, S., Zanabazar, A., Purev, B., Otgonbayar, A. E., & Gansukh, B. A. Examining the linking between the occupational health and safety practices, employee awareness, and performance. Eur. J. of Bus. and Mang. Res. 10, 162–167. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejbmr.2025.10.3.2702 (2025).

Turner, N. et al. Young workers and safety: a critical review and future research agenda. J. Saf. Res. 83, 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2022.08.006 (2022).

Hoque, I. & Shahinuzzaman, M. Task performance and occupational health and safety management systems in the garment industry of Bangladesh. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 14, 369–385. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-09-2020-0169 (2021).

Tania, F. & Sultana, N. Health hazards of garments sector in bangladesh: the case studies of Rana plaza. Malays J. Med. Biol. Res. 1, 111–117. https://doi.org/10.18034/mjmbr.v2i1.384 (2015).

Sadhra, S., Kurmi, O. P., Sadhra, S. S., Lam, K. B. H. & Ayres, J. G. Occupational COPD and job exposure matrices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 12, 725–734. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S125980 (2017).

Islam, L. N., Sultana, R. & Ferdous, K. J. Occupational health of the garment workers in Bangladesh. J. Environ. 1, 21–24 (2014).

Bajracharya, N., Magar, P. R., Karki, S., Giri, S. & Khanal An occupational health and safety issues in the construction industry in South asia: a systematic review and recommendations for improvement. J. Multidisciplinary Res. Advancements. 1, 27–31 (2023).

Khahro, S. H., Ali, T. H., Memon, N. A. & Memon, Z. A. Occupational accidents: a comparative study of construction and manufacturing industries. Curr. Sci. 118, 243–248. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27226327 (2020).

Barbosa, I. D. O., Macêdo, A. N. & Martins, V. W. B. Construction industry and its contributions to achieving the SDGs proposed by the UN: an analysis of sustainable practices. Buildings 13, 1168. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13051168 (2023).

Fei, W. et al. The critical role of the construction industry in achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs): delivering projects for the common good. Sustainability 13, 9112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169112 (2021).

Hosseinian, S. S. & Torghabeh, Z. J. Major theories of construction accident causation models: a literature review. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Technol. 4, 53. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268439084 (2012).

Reason, J. The contribution of latent human failures to the breakdown of complex systems. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 327, 475–484. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1990.0090 (1990).

Seevaparsaid-Mansingh, K. & Haupt, T. C. Construction accidents causation: an exploratory analysis. Institutional Repository Cape Peninsula Univ. Technology (2008).

Jovanović, D., Šraml, M., Matović, B. & Mićić, S. An examination of the construct and predictive validity of the self-reported speeding behavior model. Accid. Anal. Prev. 99, 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2016.11.015 (2017).

Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In Action Control. SSSP Springer Series in Social Psychology (eds Kuhl, J. & Beckmann, J.) (Springer, 1985). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-69746-32.

Xu, S., X Zou, P. & Luo, H. Impact of attitudinal ambivalence on safety behaviour in construction. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018 (7138930). https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7138930 (2018).

Conner, M. & Armitage, C. J. Extending the theory of planned behavior: a review and avenues for further research. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 28, 1429–1464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01685.x (1998).

Goh, Y. M. Binte sa’adon, N. F. Cognitive factors influencing safety behavior at height: a multimethod exploratory study. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 141, 04015003. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000972 (2015).

Arcury, T. A., et al. Work safety climate and safety practices among immigrant Latino residential construction workers. American journal of industrial medicine. 55, 736–745. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.22058 (2012).

Swedberg, R. Cambridge University Press,. Exploratory research. In The Production of Knowledge: Enhancing Progress in Social Science (eds Elman, C., Gerring, J. & Mahoney, J.) 17–41 (2020).

Creswell, J. W. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative (Prentice Hall, 2012).

Roy, S., Sowgat, T. & Mondal, J. City profile: dhaka, Bangladesh. Environ. Urban Asia. 10, 216–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975425319859126 (2019).

Hoque, M. I. & Hasan, M. Factors affecting the construction quality in Bangladesh. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBPA-03-2022-0037 (2022).

Datta, S. D. et al. Critical project management success factors analysis for the construction industry of Bangladesh. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBPA-01-2022-0006 (2023).

Hossain, M. A., Shams, S., Amin, M., Reza, M. S. & Chowdhury, T. U. Perception and barriers to implementation of intensive and extensive green roofs in Dhaka. Bangladesh Buildings. 9, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings9040079 (2019).

Bangladesh National Portal. Sylhet City Corporation. (2024). https://scc.gov.bd/site/page/ca420ff3-9d80-49fd-9c08-906ee0110975/-.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa (2006).

Maguire, M. & Delahunt, B. Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Irel. J. High. Education 9. http://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/335 (2017).

Sen, V. & Nagwanshee, R. K. Ethical issues in social science research. Res. J. Manag Sci. 5, 37–41. (2016).

Jebens, E., Mamen, A., Medbø, J. I., Knudsen, O. & Veiersted, K. B. Are elderly construction workers sufficiently fit for heavy manual labour? Ergonomics 58, 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2014.977828 (2015).

Peng, L. & Chan, A. H. Adjusting work conditions to Meet the declined health and functional capacity of older construction workers in Hong Kong. Saf. Sci. 127, 104711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104711 (2020).

Tetik, Y. Ö., Akboğa-Kale, Ö., Bayram, I. & Baradan, S. Applying decision tree algorithm to explore occupational injuries in the Turkish construction industry. J. Eng. Res. 10, 59–70. https://doi.org/10.36909/jer.12209 (2022).

Hasan, M. M., Khanam, R., Zaman, A. M. & Ibrahim, M. Occupational health and safety status of ongoing construction work in Patuakhali science and technology university, dumki, Patuakhali. J. Health Environ. Res. 3, 72–83. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.jher.20170305.11 (2017).

Gümürçinler, T. & Akboğa-Kale, Ö. Evaluation of occupational safety in restoration projects of historic buildings: risk analysis with selected projects. Buildings 13 (12), 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13123088 (2023).

Chan, D. W., Cristofaro, M., Nassereddine, H., Yiu, N. S. & Sarvari, H. Perceptions of safety climate in construction projects between workers and managers/supervisors in the developing country of Iran. Sustainability 13, 10398. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810398 (2021).

Mamin, F. A., Dey, G. & Das, S. K. Health and safety issues among construction workers in Bangladesh. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Health. 9, 13–18. https://doi.org/10.3126/ijosh.v9i1.25162 (2019).

Akboğa-Kale, Ö. & Eskisar, T. Work-related injuries and fatalities in the geotechnical site works. Ind. Health. 56 (5), 394–406. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2017-0166 (2018).

Wong, T. K. M., Man, S. S. & Chan, A. H. S. Critical factors for the use or non-use of personal protective equipment amongst construction workers. Saf. Sci. 126, 104663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104663 (2020).

Haas, E. J. The role of supervisory support on workers’ health and safety performance. Health Commun. 35, 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1563033 (2020).

Pretorius, S., Steyn, H. & Bond-Barnard, T. J. Project management maturity and project management success in developing countries. S Afr. J. Ind. Eng. 34, 36–48. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-indeng_v34_n2_a4 (2023).

Amoah, A., Berbegal-Mirabent, J. & Marimon, F. Making the management of a project successful: case of construction projects in developing countries. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 147, 04021166. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002196 (2021).

Huda, M., Soepriyono, S., Siswoyo, S. & Azizah, S. Implementation of PMBoK 5th standard to improve the performance and competitiveness of contractor companies. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advance and Scientific Innovation (ICASI) 242 (2019). https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.18-7-2019.2288604 (2019).

Guldenmund, F., Cleal, B. & Mearns, K. An exploratory study of migrant workers and safety in three European countries. Saf. Sci. 52, 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2012.05.004 (2013).

Zhang, M. & Fang, D. A cognitive analysis of why Chinese scaffolders do not use safety harnesses in construction. Constr. Manag Econ. 31, 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2013.764000 (2013).

Shabani, T., Jerie, S. & Shabani, T. A review of the role of behaviour-based procedures in work safety analysis in the medical sector of Zimbabwe. Life Cycle Reliab. Saf. Eng. 12, 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41872-023-00227-5 (2023b).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely appreciate the respondents for their invaluable support during the data collection process. They also extend their gratitude to the anonymous scholars whose insightful suggestions greatly contributed to the development of the quality of this article.

Funding

There was no financial support received for this research and/or publication of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

While the first author drafted and prepared the manuscript based on the data from his MSS (Master of Social Science) thesis, the second and third authors guided throughout the process and reviewed the manuscript. The third author reviewed the initial manuscript and suggested further improvement. The first author then refined the manuscript. The third author edited the manuscript again. Then all authors approved the current version of the manuscript for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Participants, including contractors, building owners, and construction workers, agreed to its publication for the country’s benefit. All authors approved the current version of the manuscript and are agreed to publish the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted as the first author’s Master’s thesis, with ethical approval from the relevant academic review committee (Thesis Review Committee for the Session 2017-18, Department of Social Work at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology), consisting several professors. However, this committee did not provide any ethical approval number. All sources were properly cited to avoid plagiarism.

Consent to participate

Prior to participating in the study, all building owners, contractors, and the majority of the workers who have minimal academic education gave informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from guardians of all illiterate workers. They had complete control over when to call off the interview. If respondents did not want their information to be used in the report, they might also get in touch with the researchers. All authors actively played their roles in conducting and accomplishing this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad, I., Pervin, A. & Hossain, M.I. Occupational health risks, safety essentials, and safety beliefs among construction workers in Bangladesh. Sci Rep 15, 33064 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12621-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12621-3