Abstract

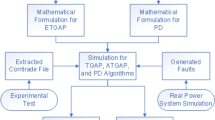

This paper presents an adaptive protection algorithm that adjusts the tripping characteristics of the differential relaying schemes in response to changes in CT saturation levels and DC component content of fault currents. Moreover, the main protection function differentiates between internal and external faults with or without CT saturation. This is accomplished by estimating the appropriate tripping characteristic slope using form and ripple factors calculated for the current signals measured at the entering and exiting terminals of the protected equipment. The modified approach aims to achieve automatic resetting to inhibit the relay operation during external faults and to avoid any delay or restriction of the relay operation during severe internal faults due to the presence of harmonics. Numerous cases, including various types of internal and external faults with or without CTs saturation and DC component, are carried out on a typical power system simulated using the ATP platform. The proposed algorithm can be performed utilizing the MATLAB software, which can receive current measurements from the ATP simulator. The simulation results manifest the functional efficiency of the suggested technique under diverse operating and fault conditions and its ability to discriminate fault location. Additionally, the response time of the suggested technique is roughly 10.0 ms in the event of internal faults, which is also appropriate for preventing the technique from functioning in the case of non-fault or external fault disturbances. Furthermore, it is able to recognize CT saturation conditions, assess the degree of current distortion, and select which feeder CT is saturated. Besides, the outcomes demonstrate the extreme simplicity, effectiveness, stability, accuracy, and reliability of the proposed algorithm. Quantitative findings from the extensive case studies indicate that the estimated ratios of the protection’s accuracy, dependability, security, and reliability are greater than 99.40%. It is applicable to Smart Grids (SGs) and Substation Automation Systems (SAS), as the algorithm is one of the applications in digital protection relays/systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Power system components require continuous monitoring and a fast protection response. The major components of the power system include synchronous generators, power transformers, large motors, feeders, and busbars. The objective of the protection is to isolate the component that is susceptible to the fault event in order to prevent any damage to the power system1. A differential current relay is essential for fast tripping the protected component, which can sense the disparity between phase currents entering and leaving the component1. The biased or percentage differential current relay is the most prevalent type of differential relays that distinguishes between differential and restraining currents2,3. If an imbalance is found between the two quantities with a presetting value, the relay will activate and trip all circuit breakers of the protected equipment4. It is the main protection for power systems because it operates instantaneously, protects the equipment against both earth and phase faults, and has a limited protection zone5. Even though the differential relay is considered to be reliable and robust, it faces many drawbacks due to nonlinear operation resulting from variations in CT characteristics, CT ratios, and fault currents accompanied by DC components6. When there is variation in the through fault current due to system configuration changes, the relay may give reduced accuracy. Hence, if the maximum through fault current is accurately determined, a proper characteristic slope can be selected, and then the relay malfunction will be avoided7. Conventional percentage differential relays may lose their selectivity property in the instances of external fault with a significant amount of DC component due to the high value of the decaying time constant, which may result in over-tripping if any CT is saturated8. Moreover, they do not operate under the low internal fault current as expected. The large quantity of fault currents may cause CT saturation within the first half-cycle or the full-cycle following fault time inception 9.

Motivation and incitement

Most traditional differential relays typically possess fixed-bias tripping characteristics. In some situations of severe CT saturation, the selection of an unsuitable restraint factor may cause the relay to malfunction10. Adaptive protection relays/systems can change relay settings online using input signals measured from local transducers or a central control system. Therefore, certain protection shortcomings can be addressed by the adaptive protections, such as (1) the relay stability during large external faults with CT saturation conditions, (2) the relay sensitivity during low internal faults, and (3) the presence of harmonics may delay or prevent relay operation in the event of severe internal faults11.

Literature review

Numerous numerical techniques were presented in the field of adaptive differential protection systems, which were used to protect various electrical elements in conventional and smart grids. Several methods based on statistical/mathematical models were employed, encompassing but not limited to alienation coefficients12,13, correlation coefficients14 transient signal analysis15, wireless communication and computer technologies16, alpha plane17, machine learning18, superimposed sequence current19, superimposed reactive energy20, limited wide area21, Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)22, Fuzzy decision and graph23, Wavelet Transform (WT) integrated with correlation analysis24, Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT)25, and Phasor Measurement Unit (PMU)26. In27, a protection scheme based on analytically derived pick-up and slope of the differential relay characteristic was presented, where its sensitivity was enhanced during internal faults using input information like rating and connection of CTs. These methods aim to ensure a proper operation and improve the protection performance, stability, sensitivity, security, accuracy and efficiency. Although some of these methods are complicated, their use is beneficial23,24,25. Three critical issues for a conventional differential overcurrent relay in28 are addressed in this study, which can be listed as follows:

-

(1)

the sensitivity and security of the relay cannot be automatically modified utilizing the prescribed low pickup differential current and the selected single restraining factor that identify the tripping and blocking zones of the operating characteristic,

-

(2)

The presence of harmonics in the event of severe internal faults will accelerate the relay operation, which originates from the DC components and CT saturation, and.

-

(3)

The relay needs a supplementary algorithm or device to define the event of external faults with CT saturation extent.

As a consequence, the implementation of an adaptation strategy for tripping characteristics is indispensable to enhance the relay stability in the instance of external faults with CT saturation.

In29, the adaptive overcurrent relay (AOCR) used the three Z-scores of the three single phase current signals (measured in the distribution system with/without Fault Current Limiters (FCLs) or with/without Distributed Generators (DGs)) to select the faulty phase and define the fault type. Also, the FCLs limit the fault current magnitude and prevent the presence of CT saturation; nevertheless, the relay couldn’t identify the fault location, whether it is internal or external29. In30, the adaptive overcurrent relay (AOCR) was contingent on Fano Factors (FFs) of current signals. It was also unable to ascertain the fault protection zone30. In31, an adaptive protection strategy for overcurrent relays, meticulously tailored to accommodate the fluctuations in electrical load, was presented. This strategy used a hybrid algorithm, which amalgamated the strengths of three preeminent metaheuristic models: Improved Harmony Search, Particle Swarm Optimization, and Differential Evolution31. The results and analyses substantiated the efficacy of the algorithm in optimizing the coordination among overcurrent relays aiming to uphold the overarching protective imperatives of the grid; moreover, the operation speed of the relay was reasonably high31.

In32, a virtual consensus-based wide area differential protection (WADP) method through cooperative control concepts and graph theory was presented. It was designed to adapt to network topology changes using the existing telecommunication connections. By implementing dynamic decision-making within protection areas, the method32 offered an efficient and high-speed solution to power grid protection. While, the paper32 primarily focused on applying the proposed virtual differential protection to support other distance protections. In33, a dynamic wide-area cooperative protection based on cooperative control of distributed multi-agent systems and graph theoretical methods was introduced. The protection decisions were collective, while a centralized master did not exist, and local information was applied. A fault detection code and a wide-area fault detection code were used for fault detection33. The suggested protection performance was studied as a backup protection for distance relays during normal, stable power swings, unstable power swings, and load encroachment conditions33. In34, the study used the slope degree of grey incidence analysis model to design a methodology for busbar protection. A grey-based busbar protection criterion was established to inspect the similarities of the superimposed currents measured by nearby CTs inside the busbar protection zone. It was seen that the methodology34 could reliably discriminate between internal and external faults. Moreover, the results demonstrated that the protection indexes of the scheme34 are satisfactory for different conditions, including fault type, high fault resistance, fault, simultaneous faults, and faults with CT saturation. In35, an integrated busbar protection scheme based on a coherence approach was applied. The approach35 had the ability to discern the faulty phase and determine the fault type and fault protection zone; besides, it could detect the case of external faults with CT saturation extent.

Contribution and paper organization

This work develops an adaptive protection mechanism that manages the tripping features of differential relay responses to change in the CT saturation levels and the content of the DC components during the current faults. The approach depends on evaluating the most convenient slope for the relay tripping characteristics by calculating the form and ripple factors of the current signals in order to finally formulate a restraint signal making the relay operation more appropriate when facing the external faults. Moreover, the estimated form and ripple factors are useful for accelerating the relay operation in the incidence of large internal fault currents with high DC components. These features enable the technique to reinforce the protection stability and security during periods of CT saturation and DC components of fault currents. Besides, its main function is to select the faulty phase(s), classify the faults, and discriminate the fault location. A typical three-phase power network is subject to a diverse range of internal and external faults, including but not limited to CT saturation and varying operating conditions. This proposal possesses the following characteristics:

-

(1)

The algorithm is able to identify steady-state conditions, and faults located on the protected component.

-

(2)

The instances of internal and external shunt faults can be swiftly differentiated,

-

(3)

The approach can be used to discriminate between external shunt faults with or without CT saturation occurrence,

-

(4)

The technique can be used to categorize fault types, select faulty phases, and discriminate fault directions,

-

(5)

The approach is able to detect CT saturation conditions and assess the extent of DC components,

-

(6)

The convenient tripping zone of the differential current protection can be neatly determined using novel mathematical models based on form and ripple factors computed for current signals of the protected component,

-

(7)

The restraining slope of the differential current relay can be automatically adjusted when the level of CT saturation or the amount of DC components changes,

-

(8)

The algorithm can be employed online and is compatible with other digital differential current relays made by different companies,

-

(9)

Local current measurements can only be used, reducing the time spent to transmit and process the local data,

-

(10)

This approach is suitable for both conventional and smart grids with a variety of voltage and power ratings,

-

(11)

The methodology can be harnessed in practice,

-

(12)

The method maintains protection stability despite the specifications of power element parameters are changed,

-

(13)

The algorithm can be applied to protect a single-phase or three-phase component or equipment,

-

(14)

The approach responds when internal faults occur, while its operation is blocked when the protected element is healthy or when external faults is existent,

-

(15)

The data window and the specified settings of the differential current algorithm can be used to alter the sensitivity and speed of fault detection, and

-

(16)

The proposed algorithm can be characterized as being smart, reliable, swift, stable, and precise,

This paper is arranged as follows: Section “Traditional biased differential relay” describes the applications, the principle of operation, and the tripping characteristics of the conventional biased differential relay made by the Siemens Company. Mathematical models and algorithm procedure for the adaptive differential current relay are elaborately explained in Section “Proposed method”. A simulation power system under study and the specifications of its components are exhibited in Section “Power system description”, which is used to validate the performance of the advanced algorithm. The simulation outcomes are described and analyzed in Section “Simulations and results analysis”. In Section “Protection scheme assessment”, the benefits of the adaptive differential current protection are enumerated, as well as a thorough comparison between the current proposed and recent published methods. Eventually, the results are concluded in Section “Conclusions”.

Traditional biased differential relay

In order to present a proposal to improve the stability of differential relay characteristics during periods of CTs saturation and DC component extent, one model of biased differential current relays (made by Siemens Company) should be described28.

Description and application

The SIPROTEC 7SS60 system is one sample of numerical differential current relays used to protect busbars. It is compatible with a wide variety of busbar configurations, and is suitable for all voltage levels. This relay is designed for diverse busbars, such as single, one and half breaker and double busbars with or without bus couplers28.

Function principle

The 7SS60 protection system operates with the differential current measuring principle to protect busbars. Its algorithm relies on Kirchhoff’s current law, which states that in a fault-free condition, the vector sum (Id) of all currents flowing into an independent busbar section must be zero. Some minor deviations from this law may be attributed to errors in CTs, inaccuracies in the matching of the CTs ratios and measurement inaccuracies. Further errors may be due to CTs saturation in the presence of large external short-circuit currents, which are counteracted by a load-dependent supplementary restraint28. The restraint current (Ir) is derived from the load condition, which arises from the summation of all the busbar current magnitudes28.

Differential relay tripping characteristics

The tripping characteristic settings of the differential relay encompass a pickup value (Id0) and a restraint factor (Ks) that considers both linear and non-linear CT errors. Tripping occurs when the estimated differential current exceeds the set characteristic, as shown in Fig. 128. The differential current low setting (Ido) ranges from 0.20 to 2.50 In, and the restraint factor (Ks) lies between 0.10 and 1.0 (in steps of 0.01)28. The threshold value (Ido) should be set above maximum load current to avoid tripping by the load current and CT errors, and it should be set at about 50% below minimum short-circuit currents to ensure tripping under minimum internal faults in power systems28. The change in the factor (Ks) alters both tripping and stabilizing areas of the relay characteristic, as depicted in Fig. 1. A high setting for this factor can improve the stability with regard to faults outside the protection zone, but it can also reduce the sensitivity of fault detection. Therefore, the Ks factor should be selected as low as possible and as high as necessary. Moreover, a sensitive differential current monitoring with the parameter Idthr can identify CT faults (such as CT short-circuits, open-circuits and reverse wiring even with load currents). The CT fault causes a differential current in the differential protection that will be then blocked, and an alarm will be declared. The setting of CT supervision differential current (Idthr) ranges from 0.1 In to 1.00 In28.

The differential current (ids(k)) at the ‘k’ sample for the ‘S’ phase of the protected busbar is calculated using the following formula:

whereas, the restraining current (irs(k)) at the ‘k’ sample for the ‘S’ phase of the protected busbar is computed as follows:

It is obvious that ids(k) and irs(k) are estimated at every sample ‘k’ by processing the sequential samples. The amplitudes of the fundamental components of ids(k) and irs(k) are Ids and Irs, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 1, the tripping characteristic of the relay during the first section ‘AB’ is determined by the following inequality28:

whereas, the tripping characteristic of the relay for the slope (Ks) during the second section ‘BC’ is contingent on the following inequality28:

For normal load or through-fault currents, the differential current quantity is almost zero, while the restraint current quantity increases instantly. Whereas, both differential and restraint currents rise at the same time in the event of internal faults. Hence, the protection relay can decide whether there is an internal or external fault condition within a few milliseconds. Certain assumptions are made in order to achieve a proper relay operation, including that the type and ratio of CTs at both busbar ends are identical, that entering and exiting currents are exactly synchronized, and that CTs are dimensioned to ensure that all CTs transform currents without saturation for a duration of at least 4.0 ms28.

Proposed method

Basic concept

It is known that any fault current signal encompasses AC with/without DC components. The shape of the current signal is measured by the form factor, and the ripple content in the signal is measured by the ripple factor36,37. Both factors are dimensionless, and their quantities are typically expressed as a percentage. The ripple factor reveals the quality of the signal, which consists of AC and some DC parts, as well as its conversion efficiency to pure AC or pure DC components. The lower value of the ripple factor indicates a proper current signal, while the greater value of the ripple factor denotes a distortion in the current signal36,37. When the form factor is approaches unity and the ripple factor vanishes, both factors indicate the steady-state condition. Hence, a pure AC current signal is obtained (i.e., the signal is clear from the DC component content and without CT saturation extent). As a consequence, the ripple and form factors can be used to detect the CT saturation condition and the DC component of current signals. Furthermore, both factors are able to control a restraint factor/signal to prevent the differential relay operation during external faults with CT saturation presence. The characteristic slope of the differential protection can be adjusted online, and it can be modified based on the form and ripple factors of the current signals measured at the two terminals of the power system component. As a result, adaptive differential current relay characteristics based on the form and ripple factors of the busbar current signals can be established. The subsequent section will explain the numerical method for estimating the form and ripple factors.

Form and ripple factors

-

(a)

For conversion to DC output:

The absolute value of the phase current waveform is regarded as a single-phase full-wave rectifier bridge. The ratio of the RMS value to the DC value of the current signal is defined as the Form Factor (FFi)36,37, which is a measure of the shape of the signal. The form factor (FFi) can be expressed as follows36,37:

The Ripple Factor (RFi) is another essential parameter used to measure the ripple content in the current signal36,37. Thus, it represents the smoothness of the current waveform. The RFi is defined as the ratio between the effective RMS value of the AC component and the DC value of the measured current. The ripple factor (RFi) can be computed as follows36,37:

The full-cycle RMS value (IsRMS) of the current signal can be calculated as follows36,37:

The full-cycle DC current (IsDC) is defined as the average value of the current signal per one cycle,36,37. The full-cycle DC component of the current signal can be quantified as follows:

The proposed technique can apply the concept of moving data set, for calculating the form and ripple factors, whose size can be selected within the range of one cycle to a sub-cycle. The size of the data set can be configured as: 1/8, 1/4, 1/2, 3/4, or one cycle. In this study, the half-cycle period is selected to accelerate the relay operation. For this selection, the RMS and DC values (IsRMS and IsDC) of the sinusoidal current signal can be calculated to obtain the form and ripple factors as described below.

The half-cycle RMS value of the current signal is quantified as follows36,37:

The half-cycle DC value of the current signal is quantified as follows36,37:

The half-cycle effective RMS value of the AC component for the current signal is calculated as follows36,37:

The half-cycle form factor (FFi) for the current signal is given by36,37:

The half-cycle ripple factor (RFi) for the current signal is given by36,37:

Table 1 lists the normal values of the form and ripple factors for ideal sinusoidal waveforms, in the instances of normal operation and steady-state fault current, at various data windows (including 1/8, 1/4, 1/2, 3/4, and one cycle).

-

(b)

For conversion to AC output:

When converting to AC output, ripples may arise as a result of unfavorable DC components. This means that the AC signals should be pure sinusoidal waveforms (i.e., without any DC components) in the process of ideal conversion. Consider RFix to be the ratio between the effective value of the DC/ripple component and the RMS value of the AC component of the measured current. The mathematical formula for estimating the ripple factor (RFix) is as follows:

Also, assume that FFix is the ratio between the RMS value and the RMS value of the AC component of the measured current. The mathematical equation for evaluating the form factor (FFix) is as follows:

When the data set size is a half-cycle, the values of RFix and FFix can be quantified using the following formula:

In fact, different unwanted ripples appear in power systems. Some of these ripples are inserted in the sinusoidal current signals due to DC component and CT saturation conditions. The CT saturation event causes loss of portions from the CT secondary current waveform, and this current loss flows in the CT iron core. Many applications of protection and control systems require that the ripple content doesn’t exceed a specified value, or the adaptation concept is used to avoid its negative effects on the action of these systems. Throughout this work, the developed adaptation procedure includes appropriate on-line modifying of the differential relay curves based on the estimated form and ripple factors, thus enabling improvement of protection stabilization for the situation of close external faults with high DC components.

Adaptive differential relay scheme

The current data, measured at both ends of the protected equipment, are sufficient for processing the proposed algorithm utilizing the signals processing principal. The proposed algorithm identifies the fault condition, discriminates between internal and external faults, detects CT saturation, and estimates on-line the convenient slope for the differential relay characteristics. The more suitable slope of differential relay characteristic aims to make adaptive characteristics during CT saturation period to avoid false relay operation in the event of external faults. The adaptation process leads to extending the stabilizing area of the relay characteristic or accelerating the relay tripping during large internal fault currents with high DC components (i.e., relay operation is without pickup time delay). This is accomplished using the form and ripple factors calculated for each CT current signal. The strategy of the modified differential current protection can be described in the following sections:

Determination of fault inception instant (kf )

The proposed algorithm identifies the fault inception instant (kf) using the first derivative estimated for each CT current signal, and for each feeder connected to the protected busbar. In the majority of cases, the first derivative of the pre-fault current is negligible with respect to the first derivative of the post-fault current. Hence, the first derivative corresponding to each phase CT current can be considered a proper method for fault detection. In this method, if the first derivative has a value above a threshold value, a fault is ascertained; this is for at least one phase current signal. To determine the fault inception instant from the CT secondary current (ism(k)) of each circuit ‘m’ and for each ‘S’ phase, the first derivative (Fism(k)) can be obtained as follows:

where, h is the sampling time interval, and fs is the sampling frequency (h = 1/fs).

Then the proposed technique compares the estimated factor (Fism(k)) with a setting value (Fs = 200% Fm) to determine the fault time inception (kf), where Fm is the maximum first derivative obtained from the stored pre-fault current. If the first derivative (Fism(k)) is greater than the setting value (Fs), then the fault is identified at a sample index of kf = k.

Fault directionality

The directionality factor (DFs), calculated using the input and output currents for each data window of each ‘S’ phase of the protected equipment, can discriminate between the internal and external faults with/without CT saturation condition. The factor (DFs) is estimated instantly as follows:

where as, the factor (DFsv) can be formulated for each data window as follows:

To discriminate between the cases of normal operation and external and internal faults with/without CT saturation presence, the proposed algorithm relies on the following rules:

-

(I)

Normal operation and external fault without CT saturation conditions.

If DFa = DFb = DFc = + 1 (i.e. the three directionality factors are + 1 for the three phases of the protected equipment), then this case is normal operating conditions or external faults without CT saturation extent. This condition results in DFav = DFbv = DFcv = + 1 during the periods of normal operation and external fault without CT saturation. Besides, the evaluated differential currents (ida(k), idb(k) and idc(k)) are below the set characteristic for the three phases of the protected equipment.

-

(II)

Internal fault condition.

If DFa = − 1.0, DFb = − 1.0, or DFc = − 1.0 (i.e., the directionality factor is ‘− 1.0’ for at least one phase of the protected equipment during the first data window after the fault time inception), then this case indicates to a fault located inside the protection zone. This state leads to DFav < 0, DFbv < 0 or DFcv < 0 during the period of internal fault. Additionally, the estimated differential current (ida(k), idb(k) or idc(k)) is above the set characteristic for at least one phase of the protected equipment. Hence, the faulted equipment must be isolated from the remaining power system.

-

(III)

External fault with CT saturation condition.

In this situation, consider the time interval of the free saturated portion (after fault inception) for the distorted secondary current is at least one-eighths cycle (i.e., the minimum time-to-saturation is 1/8 cycle) because the CT secondary current does not saturate suddenly. Due to the case of external fault with CT saturation extent, the values of the three directionality factors (DFa, DFb, and DFc) or (DFav, DFbv, and DFcv) are positive values during the first data window after fault inception; besides the value of DFav, DFbv, or DFcv isn’t equal to unity (i.e., the directionality factor is equal + 1.0 during the first window after the fault time inception for at least one phase of the protected equipment). In other words, the value of directionality factor for at least one phase isn’t equal to + 1.0, and the values of the other directionality factors of the remaining phases are equal to + 1.0. This case results in + 1.0 > DFav ≥ 0.0, + 1.0 > DFbv ≥ 0.0 or + 1.0 > DFcv ≥ 0.0 during the time snap of external fault with CT saturation condition. Moreover, the calculated differential currents (ida(k), idb(k), and idc(k)) are below the set characteristic for the three phases during the free saturated portions of the secondary currents, while they are above the set characteristic for at least one phase during the saturated portions of secondary currents. Consequently, this event makes the protection scheme implements the adaptation process for relay operating characteristics. The values range of the three-phase directionality factors and differential currents for each fault type is given in Table 2. As shown in the table, it is obvious that the values of directionality factors are restricted between − 1.0 and + 1.0, while the magnitudes of differential currents aren’t limited.

CT saturation detection

The proposed algorithm performs three criteria sequentially processed (during the first window after the fault time inception) to affirm the CT saturation condition as follows:

-

(I)

The estimated three-phase directionality factors are used to detect the CT saturation state based on the rules mentioned in the previous section.

-

(II)

The calculated form and ripple factors of each individual CT secondary current can be used to identify the CT saturation condition. This is based on the following concept:

In the cases of normal operation, no CT saturation and no DC component extent in fault currents, the factor (RFi) is fixed and close to the value of 1.21 (i.e., RFix = 0.83). This means that the form and ripple factors (FFi, RFi, FFix and RFix) are normal values as given in Table 1. Whereas in the cases of CT saturation extent and DC component content in the fault currents, the factor (RFi) is not constant, and it becomes greater than a selected threshold value of )1.21 + Δ(= 1.31. Also, the factor (RFix) is not constant, and it becomes lower than the selected threshold value of 0.76 (i.e., 1/1.31 = 0.76). The values of the two factors (FFi and RFi) change according to the CT saturation level and the asymmetrical component extent. The more CT saturation severity level, the more values of form and ripple factors (FFi and RFi) and also the lower values of the two factors (FFix and RFix).

-

(III)

The differential current (ids(k)) is useful to differentiate between internal fault and external fault with CT saturation. If the magnitude of the differential current quantity, during the interval following the fault time inception and before the CT saturates for at least one-eighths cycle, is lower than a predefined threshold value, a fault location is outside the equipment protection zone; otherwise, the fault is internal. The external fault with CT saturation extent is defined from the calculated differential current (ids(k)), which is above the set characteristic after a delay time (Td) from the fault time starting. After the delay time (Td), the differential current (ids(k)) transfers between the tripping and blocking areas of the relay characteristic.

Calculation of adaptive characteristic slope

The protection technique is based on estimating the suitable slope for the relay characteristics, using the form and ripple factors (FFi and RFi) or (FFix and RFix) calculated for the current signals, in order to produce a restraint signal that prevents the relay operation during external faults with CT saturation presence. In this instance, the stabilizing area must be increased with the increase in the CT saturation level. The greater the form and ripple factors (FFi and RFi), the greater the operating characteristic slope (Ks) of the differential relay. As a result, the relation between the characteristic slope (Ks) and the two factors (FFi and RFi) is proportional linear. The convenient slope is estimated for each data window of half-cycle. For estimating the operating characteristic slope (Ks), the two factors (FFix and RFix) are used.

In the ideal case, IsDC = 0 and IsRMS = IsacRMS. As a result, FFix = + 1 and RFix = 0. Whereas, in the presence of the CT saturation and the DC components of the fault current, IsDC > 0 and IsRMS > IsacRMS. As a consequence, FFix > + 1 and RFix > 0.

In this scenario, consider that the selected data window is half-cycle and the differential relay characteristic with slope Ks varies from 0.1 to 1.0 like Siemens manufacturer28. Initially, select the slope Ks1 = 0.0 when FFi = 1.0 (for the ideal case) and Ks1 = 1 when FFi = 2.3 (for the worst case in Table 1). Also, select the slope Ks2 = 0.0 when RFi = 0.0 (for the ideal case) and Ks2 = 1 when RFi = 2.08 (for the worst case in Table 1). By substituting these values into both two linear Eqs. (21) and (25), the values of the constants c1, c2, c3 and c4 are 0.77, − 0.77, 0.48 and 0.0, respectively. The adaptive tripping characteristics slopes (Ks1 and Ks2) can be calculated by Eqs. (24) and (28).

From the tripping characteristics slopes (Ks1 and Ks2), it is often more convenient to select:

-

The tripping characteristic slopes Ks1 = Ks2 = 0.0 for the ideal case without ripples content, where FFix = + 1 and RFix = 0, respectively,

-

The tripping characteristic slopes Ks1 = 0.23 and Ks2 = 0.4 are suitable for normal operation with ripple content and for no CT saturation extent, due to the linear CTs errors, where FFix = 1.30 and RFix = 0.83, respectively, and.

-

The operating characteristic slopes Ks1 = Ks2 = + 1 are suitable for the worst degree of CT saturation where FFix = 2.30 and RFix = 2.08, respectively, due to the linear and non-linear CT errors.

Figure 2a illustrates the relation between the two tripping characteristics slopes (Ks1 and Ks2) and the two factors (FFix and RFix), respectively. Now, the online adaptation process can be applied by selecting only one formula of the two mathematical formulas (Ks1 and Ks2) for calculating the suitable operating characteristic slope.

(a) The relation between the two tripping characteristics slopes (Ks1 and Ks2) and the two factors (FFix and RFix), respectively. (b) Adaptive characteristics of the biased differential relay. (c) Flow chart of the adaptive differential protection scheme based on the form and ripple factors for the current signals.

In this study, the form and ripple factors (FFix and RFix) can be used to:

-

(1)

Figure out and assess the intensity level of the CT saturation,

-

(2)

Estimate the DC component percentage in the fault current, and.

-

(3)

Determine the curve slope for the adaptive differential relay characteristic.

Adaptive operating characteristics

Figure 2b shows the adaptive characteristics of the biased differential relay. The novel adaptive tripping characteristics based on the form and ripple factors estimated for the measured currents represent a development for the conventional differential current relays. Each operating characteristic includes three regions as follows:

-

(I)

The tripping zone, which can be used to detect internal fault events, then the faulted equipment must be isolated from the remaining power system. Consequently, the proposed scheme action sets the trip signal to a high value of (1),

-

(II)

The blocking zone, which can be used to prevent isolating/tripping equipment CBs in the case of external faults or normal operating instances. As a consequence, its action holds the trip signal to a low value of (0), and

-

(III)

The adaptive zone, which can be used to adjust the tripping characteristic of the differential current relay in response to CT saturation extent or DC component content of fault currents. This is accomplished by estimating the suitable slope for the relay characteristic using the form and ripple factors calculated for the measured current signals to produce a convenient restraint factor/signal. The relay operation during the external faults with CT saturation can be inhibited. Moreover, it performs other protection functions to differentiate between the instances of internal and external faults.

Adaptive algorithm procedure

Figure 2c presents the flow chart of the adaptive differential protection scheme based on the form and ripple factors for the measured current signals measured at the input and output terminals of the protected power element. The proposed algorithm of adaptive differential protection characteristics can be sequentially processed as follows:

-

(1)

Measure the data of each ‘S’ phase secondary current signal (ism(k)) for each branch (m) connected to the protected equipment,

-

(2)

Select the setting value (Fs) of the first derivative,

-

(3)

Calculate the first derivative (Fism(k)) for each secondary current (ism(k)) measured from each phase CT. This is to identify the fault instant (kf); a transition is detected for each phase and for each feeder connected to the equipment,

-

(4)

Set the number of samples per cycle and the number of samples per moving data window (Ns and Nw, respectively),

-

(5)

Estimate the phase directionality factors (DFa, DFb, and DFc) and (DFav, DFbv, and DFcv),

-

(6)

Define the event of external faults without CT saturation using the phase directionality factors (DFav, DFbv, and DFcv),

-

(7)

Select the ripple factor limit (RFx),

-

(8)

Estimate the maximum values of form and ripple factors (FFix, RFix, FFi and RFi) for all CTs secondary current signals (ism(k)),

-

(9)

Set the equipment nominal current, pickup differential current, and the minimum and maximum slopes of the characteristic curve (In, Ido, KsMIN, and KsMAX, respectively),

-

(10)

Evaluate the new tripping characteristic slope (Ks = Ks1 or Ks = Ks2) using the maximum values of the form and ripple factors (FFix and RFix), which is able to modify the ratio between the stabilizing and tripping zones within the differential relay characteristic curve,

-

(11)

Calculate the vector sum of the differential current (ids(k)) and the algebraic sum of the restraining current (irs(k)) using the measured secondary currents for each phase of the protected equipment,

-

(12)

Compare between the differential and restraining currents (ids and Id0 + Ks × irs) for each phase,

-

(13)

Differentiate between the instances of internal and external faults with CT saturation extent, and

-

(14)

A relay response is as follows:

-

(i)

In the instance of internal faults: Trip the CBs of the protected equipment,

-

(ii)

In the instance of external faults without CT saturation condition: Block the CBs of the protected equipment,

-

(iii)

In the instance of external faults with CT saturation condition: execute the online adaptation process of the differential relay curve during the periods of CT saturation and DC component content of the fault current.

-

(i)

Power system description

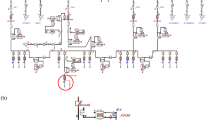

The SLD of the power system model under study is shown in Fig. 3, which is used to verify the developed scheme. The model is a segment of a medium-voltage power system. It is composed of double-circuits of 19.57 kV; each TL has a length of 100 km and extends between a synchronous machine and a connected electrical network via two busbars (BB1 and BB2), besides three electrical loads. Each TL is represented by distributed parameters, and the frequency dependence of the line parameters is taken into account. The components of the system model, simulated by the Alternative Transient Program (ATP), are based on realistic parameters given in Appendix 138. To validate the proposed technique, extensive simulation case studies have been carried out under variable operating and fault conditions using the ATP software, and the algorithm operation has been implemented using the MATLAB/M-file environment.

Simulations and results analysis

In the proposed approach, the data of three-phase currents are taken from the four circuits connected to the first busbar (BB1). The data is used to evaluate the first derivative, the directionality factors, and the form and ripple factors for each current signal, the adaptive slope, and the differential and restraint currents for each phase to perform the adaptation process. This work aims to adjust the differential relay characteristics in the case of changes in CT saturation level and the DC component content of fault currents (to enhance the relay stability and security). In this study, the CT distorted currents and DC components arise from both internal and external faults. Moreover, some assumptions are required in order to get a proper relay operation as follows: (1) identical CT type on both ends of the protected equipment, (2) equal CT ratio, (3) currents at both BB1 ends are exactly synchronized, and (4) CTs are dimensioned such that all CTs transform currents without saturation for a time at least equals 2.5 ms. The BB1 currents are generated using the ATP program with a sampling time of 0.2 ms, and the total simulation time is 0.3 s (i.e., the total number of samples is Nsim = 1500 samples). Appendix 2 contains the input data of the proposed protection algorithm.

Numerous simulation situations have been tested under various operating and fault conditions. The performance of the algorithm is evaluated under the impact of variations of fault and power system parameters such as fault type (SLG, DLG, DL and 3LG), fault resistance (0–200 Ω), fault inception angle (0–360 °), fault location (internal/external), CT burden (0–500 Ω), CT ratio (12,000/1–1000/1) and power flow angle. For each case study, consider the external faults are situated at the point F1 located on 25% of TL2 length starting from the relay place (installed at busbar BB1), and the internal faults are located at the point F2 located on the busbar BB1. Also, assume that the power system is loaded before the fault inception. The pre-fault operating conditions of the simulated power system are included in Appendix 1. For each case, δ1= 30°, δ2 = 0°, F1Operated = F2Operated = 50 Hz, and V1Max = V2Max = 16.063 kV.

Case study 1: external SLG fault with CT saturation

In this case study, the simulation is carried out to evaluate the performance of the proposed technique in the instance of the external fault with CT saturation extent. An external SLG fault without fault resistance (Rf = 0 Ω) is simulated at the point F1 located at 25% of TL2 length for the ‘A’ phase. For this case, the fault inception time is tf = 0.103 S. This means that the sample index where the fault time inception is kf = 515. The CTR is changed from 12,000/1 to 1000/1 for each CT of all feeders connected to the BB1. The CT burden for all feeders is Rb = 0.5 + j0.0 Ω except the CT burden Rb = 500 Ω for ‘A’ phase CT of the third branch (TL2). Figures 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 show the simulation results for case study 1. Figures 4a–c present the three-phase secondary currents of the four circuits (including generator, TL1, TL2 and Load ‘2’ circuits) connected to the protected busbar (BB1), respectively, in the case of the external SLG fault with CT saturation. Figure 4d plots the primary and saturated secondary currents (referred to as the primary side) for the ‘A’ phase of the branch of TL2 (i.e., the faulted and third circuit). It is noticed that for the ‘A’ phase of the faulted circuit, the current signal during the fault time interval is higher than the pre-fault current; the fault current is greater than 6 × In, and the current signal is with a large asymmetrical component. It is obvious that the high magnitude of short-circuit current, the low CTR, the large CT burden, and the asymmetry in the current waveform during the transient period are attributed to CT saturation for the ‘A’ phase current of the faulted circuit (TL2). Also, it is seen that the above-mentioned reasons result in low time-to-saturation, where the CT saturation condition reveals during the first half-cycle of the fault time.

(a) The ‘A’ phase secondary currents of the four feeders. (b) The ‘B’ phase secondary currents of the four feeders. (c) The ‘C’ phase secondary currents of the four feeders. (d) The ‘A’ phase primary and secondary (referred to primary side) currents of the third feeder (TL2 = the faulted feeder). (a-d) Simulation current signals for case study 1.

(a) The input and output secondary current signals (iain and iaout) for the ‘A’ phase of BB1. (b) The input and output secondary current signals (ibin and ibout) for the ‘B’ phase of BB1. (c) The input and output secondary current signals (icin and icout) for the ‘C’ phase of BB1. (d) The instantaneous values of three-phase directionality factors (DFa, DFb and DFc) in the case of external fault with CT saturation. (a–d) Simulation current signals and the directionality factors for case study1.

(a) The average values of three phases directionality factors (DFav, DFbv and DFcv) in the case of external fault with CT saturation. (b) The calculated maximum form and ripple factors (FFi and RFi). (c) The calculated form and ripple factors (FFix and RFix). (d) The calculated operating characteristic slope of differential relay (Ks1 and Ks2). (a–d). Response of adaptive busbar differential relay for case study 1.

(a) The instantaneous differential and restraining current signals (ida and Id0 + Ks2 × ira) for the ‘A’ phase of BB1. (b) The instantaneous differential and restraining current signals (idb and Id0 + Ks2 × irb) for the ‘B’ phase of BB1. (c) The instantaneous differential and restraining current signals (idc and Id0 + Ks2 × irc) for the ‘C’ phase of BB1. (a–c) The calculated instantaneous differential and restraining current signals for case study 1.

(a) The average value of differential and restraining current signals (ida and Id0 + Ks2 × ira) for the ‘A’ phase of BB1. (b) The average value of differential and restraining current signals (idb and Id0 + Ks2 × irb) for the ‘B’ phase of BB1. (c) The average value of differential and restraining current signals (idc and Id0 + Ks2 × irc) for the ‘C’ phase of BB1. (d)The three-phase directionality factors (DFa, DFb and DFc) in the cases of normal operation and external fault without CT saturation and Rb = 0.5 Ω. (a–c) The calculated average differential and restraining current signals for case study 1.

Figures 5a–c show the calculated input and output current signals of the A, B and C phases for the protected busbar (BB1), respectively. As illustrated in Figs. 5b–c, the input and output current signals of ‘B’ and ‘C’ phases are in phase and identical before and during the fault span. Whereas, the input and output current signals for the ‘A’ phase of BB1 are symmetrical before the fault time, while their values are slightly out of phase during the first four cycles of the fault time. This is a result of the CT saturation extent, as depicted in Fig. 5a. Figure 5d offers the instantaneous values of the three-phase directionality factors (DFa, DFb and DFc) in the case of the external fault with CT saturation for the ‘A’ phase of the faulted circuit (TL2). As shown in Fig. 5d, It is noticed that the instantaneous values of DFb = DFc = + 1.0 before and during the fault time, while DFa = + 1.0 before the fault inception and DFa = − 1.0 at discrete intervals during the external fault time due to the CT saturation event. Moreover, DFa is changed from the value of 1.0 to − 1.0 and vice versa during the fault time, but the majority of fault time DFa = 1.0. Thus, DFa indicates the occurrence of CT saturation state for the ‘A’ phase current signal, while the values of DFb and DFc affirm that there is no CT saturation condition for the two current signals of ‘B’ and ‘C’ phases.

Figure 6a shows the average values of the three-phase directionality factors (DFav, DFbv, and DFcv) for each data window, whose interval is selected as a half-cycle. As seen in Fig. 6a, in the case of external fault with CT saturation extent, the average values (DFav, DFbv, and DFcv) of the three directionality factors are positive values; and the average values of DFa = 0.88 (during the first window after the fault time inception). These values prove that the fault type is external with ‘A’ phase CT saturation. This is because the three directionality factors (DFav, DFbv, and DFcv) are positive, and the values of DFa exceed 1.0. Additionally, the calculated differential currents (ida(k), idb(k), and idc(k)) are below the set characteristic (i.e., the operating points are located within the blocking area) for the three phases of the protected element during the first window of the fault time inception. Figure 6b depicts the calculated maximum form and ripple factors, FFi and RFi estimated for the ‘A’ phase of the TL2 circuit. As shown in Fig. 6b, FFi ≈ 1.57 and RFi ≈ 1.21 during the pre-fault and the steady-state fault period (i.e., fault current without DC component extent). The two factors FFi and RFi become greater than 1.65 and 1.31, respectively, during the distorted portions and the large DC component extent in the saturated secondary current; and their values are the same pre-fault values during the unsaturated portions for the ‘A’ phase secondary current of the faulted circuit. Figure 6c plots the estimated form and ripple factors, FFix and RFix, (estimated for ‘A’ phase of the TL2 circuit). As shown in Fig. 6c, FFix ≈ 1.30 and RFix ≈ 0.83 during the pre-fault and the steady-state fault conditions. The two factors (FFix and RFix) are less than 1.26 and 0.76, respectively, during the saturated portions and the large DC component. Their values resemble those of the pre-fault values during the free saturation portions of the ‘A’ phase current signal. Figure 6d displays the estimated restraint factors (Ks1 and Ks2) of the adaptive differential relay, where their numerical values are modified with the changes of CT saturation level and the DC component content of the fault current. As mentioned before, the two slopes (Ks1 and Ks2) are based on the calculated form and ripple factors (FFix and RFix), respectively.

Figures 7a–c illustrate the instantaneous differential and restraining current signals (ids and Id0 + Ks2 × irs) for the A, B and C phases of the protected busbar (BB1), respectively. Figure 7a shows the values of ida ≈ 0 (which correspond to RFi ≈ 1.21) before the fault time inception and during the free saturation portions of the fault current, while the values of ida become larger (which correspond to the RFi values ≥ 1.31) during the saturated portions for the ‘A’ phase fault current signal. Figures 8a–c present the average values of the differential and restraining current signals (ids and Id0 + Ks2 × irs) of the BB1 three phases, which are estimated for each half-cycle data window of the current signal. The mathematical formula of the adaptive characteristic (Id0 + Ks2 × irs) includes three variables as follows: the pickup value of differential current (Id0), the adaptive slope (Ks2), and the restraining current signal (irs). In this case study, it is observed that the three-phase differential currents (ida, idb and idc) are lower than the three-phase restraining currents ((Id0 + Ks2 × ira), (Id0 + Ks2 × irb), and (Id0 + Ks2 × irc)), respectively, as depicted in Figs. 8a–c. Thus, this makes the operating points concentrated inside the stabilizing zone of the relay operating characteristic. As a result, the proposed relay prevents isolating the CBs of the busbar (BB1). Figure 8d plots the three-phase directionality factors (DFa, DFb, and DFc) in the instance of the external fault without CT saturation and Rb = 0.5 Ω for each CT of the protected busbar (BB1). It is clear that DFa = DFb = DFc = 1.0 during the time periods of the normal operation and the external fault without CT saturation condition (as shown in Fig. 8d). Therefore, the protection scheme holds a trip signal to low (0) in the case of external fault without/with CT saturation presence.

From the extensive simulation results, it is obvious that the adaptive differential current relay, based on the estimated form and ripple factors of the measured current signals is able to determine the instant fault onset, detect CT saturation conditions, identify the fault location zone (whether it is an internal or external fault), and efficiently adjust its tripping characteristics according to the change in the CT saturation level and the DC component. Moreover, it has the ability to differentiate between external faults with and without CT saturation extent, and it can define the CT saturation condition, identify the distorted and undistorted portions of the current waveform, assess the CT saturation level, and select which feeder CT is saturated.

(c) The ‘C’ phase secondary currents of the four feeders. (d) The ‘A’ phase primary and secondary (referred to primary side) currents of the third feeder (TL2 = the faulted feeder). (a–d) Simulation current signals for case study 1.

Case study 2 : internal SLG fault with CT saturation

This case examines the performance of the proposed scheme in the event of internal SLG (A-G) fault with CT saturation condition. The fault is without fault resistance (Rf = 0.0 Ω), and it is placed at the point F2 on BB1. In this case study, the operating conditions of the power system parameters are the same as those of in case 1, except that the CTR of the CT for each feeder is changed from 1000/1 to 12,000/1, and the CT burden is 0.5 + j0.0 Ω for each CT. Figures 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13 present the simulation results for case study 2. Figure 9a–c depict the three-phase secondary currents for the four branches connected to BB1 in the event of the internal SLG (A-G) fault with CT saturation. Figure 9d shows the primary and saturated secondary (referred to as primary side) currents for the ‘A’ phase of the generator circuit. It is noticed that the current quantity (for the ‘A’ phase of the generator circuit) during the fault interval is higher than the pre-fault current quantity. Its magnitude is greater than 7 × In, and the current signal is accompanied by a large DC component. For the ‘A’ phase fault current of the generator circuit, the large magnitude of the fault current with the high DC component cause the distorted secondary current, as depicted in Fig. 9d. In this case, the CT saturation situation appears after five cycles from the fault time inception. As a consequence, the protection scheme should isolate rapidly the faulted BB1 to avoid the CT saturation. In this instance, the internal fault associated with the presence of CT saturation is analyzed and discussed.

(a) The ‘A’ phase secondary currents of the four feeders. (b) The ‘B’ phase secondary currents of the four feeders. (c) The ‘C’ phase secondary currents of the four feeders. (d) The ‘A’ phase primary and secondary (referred to primary side) currents of the first branch (the generator circuit). (a–d) Simulation current signals for case study 2.

(a) The input and output secondary current signals (iain and iaout) for the ‘A’ phase of BB1. (b) The input and output secondary current signals (ibin and ibout) for the ‘B’ phase of BB1. (c) The input and output secondary current signals (icin and icout) for the ‘C’ phase of BB1. (d) The instantaneous values of three phases directionality factors (DFa, DFb and DFc) in the case of internal fault. (a–d) simulation current signals and the directionality factors for case study 2.

(a) The average values of three phases directionality factors (DFav, DFbv and DFcv) in the case of internal SLG fault with CT saturation. (b) The calculated maximum form and ripple factors (FFi and RFi). (c) The calculated form and ripple factors (FFix and RFix). (d) The calculated operating characteristic slope of differential relay (Ks1 and Ks2). (a–d) Response of adaptive busbar differential relay for case study 2.

(a) The instantaneous differential and restraining current signals for ‘A’ phase of BB1 (ida and Id0 + Ks2 × ira). (b) The instantaneous differential and restraining current signals for ‘B’ phase of BB1 (idb and Id0 + Ks2 × irb). (c) The instantaneous differential and restraining current signals for ‘C’ phase of BB1 (idc and Id0 + Ks2 × irc). (a–c) The calculated instantaneous differential and restraining current signals for case study 2.

(a) The average value of differential and restraining current signals (ida and Id0 + Ks2 × ira) for the ‘A’ phase of BB1. (b) The average value of differential and restraining current signals (idb and Id0 + Ks2 × irb) for the ‘B’ phase of BB1. (c) The average value of differential and restraining current signals (idc and Id0 + Ks2 × irc) for the ‘C’ phase of BB1. (a–c) The calculated average differential and restraining current signals for case study 2.

Figures 10a–c offer the estimated input and output current signals of the A, B and C phases for the protected busbar (BB1), respectively. The input and output current signals of the ‘B’ and ‘C’ phases are in phase and equal before and during the fault time, while the input and output current signals for the ‘A’ phase of the busbar (BB1) are identical before the fault span and their values are unsymmetrical during the fault interval. Figure 10d demonstrates the instantaneous values of the three-phase directionality factors (DFa, DFb, and DFc) in the incidence of the internal fault accompanied by CT saturation. As obvious in Fig. 10d, the DFa = DFb = DFc = 1.0 during the normal operation period, while the DFa = − 1.0 and DFb = DFc = + 1.0 during the first data window after the commencement of the fault time. Figure 11a reveals the average values of the three-phase directionality factors (DFav, DFbv, and DFcv) computed for each data window of the fault current. The three-phase directionality factors assure that the fault location is within the BB1 protection zone, and its type is SLG (A-G) fault. This is because the values of the factor (DFav) are negative, while the values of the factors (DFbv and DFcv) are positive. Moreover, the estimated differential current (ida(k)) for the ‘A’ phase of the protected busbar is above the set characteristic (i.e., the operating points are located in the tripping area within the differential relay characteristic). Figure 11b depicts the calculated maximum form and ripple factors (FFi and RFi ) for the ‘A’ phase of the generator circuit. As shown in Fig. 11b, FFi ≈ 1.57 and RFi ≈ 1.21 during the pre-fault condition (i.e., during the normal operation period). The two factors (FFi and RFi) become greater than 1.65 and 1.31, respectively, during the interval of asymmetrical fault current (i.e., the period of DC component extent). Figure 11c illustrates the estimated form and ripple factors (FFix and RFix) calculated for the ‘A’ phase current of the generator circuit. As illustrated in Fig. 11c, FFix ≈ 1.30 and RFix ≈ 0.83 during the normal operation period, while the two factors become less than 1.26 and 0.76, respectively, during the large DC component. Figure 11d displays the suitable operating characteristic slopes (Ks1 and Ks2) of the adaptive differential current relay for case study 2.

Figures 12a-c illustrate the instantaneous differential and restraining current signals (ids and Id0 + Ks2 × irs) for the three phases of the protected busbar (BB1) in the event of the internal SLG (A-G) fault with CT saturation. Figure 12a shows the values of ida ≈ 0.0 (which correspond to the values of RFi ≈ 1.21) before the fault time inception, while the values of ida become larger (which correspond to the RFix values that are greater than 1.31) during the fault time. The values of idb ≈ idc ≈ 0.0 before and during the fault time, as depicted Fig. 12b–c. Figures 13a–c present the average values of the differential and restraining current signals (ids and Id0 + Ks2 × irs) for the three phases of the protected busbar (BB1). In this case study, it is clear that the three-phase differential currents (ida, idb and idc) are lower than the three-phase restraining currents ((Id0 + Ks2 × ira), (Id0 + Ks2 × irb), and (Id0 + Ks2 × irc)), respectively, as depicted in Fig. 13a–c. Consequently, the operating points are located inside the tripping zone of the relay characteristic curve. Hence, this assures that the fault location is internal, and the fault type is SLG (A-G). Thus, a tripping signal is sent to the CBs for isolating the faulted busbar (BB1) from the remaining power system. This is accomplished by disconnecting the CBs of the four branches connected to the busbar (BB1). The protection scheme sets the tripping signal to high (1) in the situation of the internal fault.

To further investigate the numerical accuracy and robustness of the proposed method, many study cases have been simulated under the influence of normal operation with varying electrical loads and running power factor. The load changes from 1.0 to 20% of the rated load (with step 1.0%) at running power factor = 0.85, and the running power factor is altered from 0.8 to 1.0 (with step 0.1) at the same rated real power. It is also examined under the effect of different fault conditions, including fault zones (internal and external), faulty phases (A-G, B-G, C-G, A-B-G, B-C-G, C-A-G, A-B, B-C, C-A, and A-B-C-G), fault resistances (Rf), fault inception times (tf), fault locations on TL2 length, and various CT saturation levels. The fault resistance (Rf) changes from 0.2 to 200 Ω (with step 0.2 Ω), and the fault inception time (tf) changes from 0.100 to 0.120 Sec (with step 0.001 Sec) with varying the faulty phase(s). The level of the CT saturation could be elevated by reducing the Current Transformer Ratio (CTR) and/or increasing the CT burden (Rb).

The performance of the Adaptive Differential Overcurrent Relay (ADOCR) for the diverse scenarios is given in Table 3. The table reveals that the developed ADOCR responds to the instance of internal faults, while it remains inactive in the situation of normal operations or external faults with/without CT saturation.

Table 4 presents the assessment of the protection characteristics for the proposed scheme. The ratios of the protection algorithm’s dependability, security, reliability, and accuracy exceed 99.40%, as indicated by Table 4. Finally, a comparative evaluation of the proposed ADOCR with the existing ADOCRs is held, which clearly indicates the superiority of the proposed ADOCR, as shown in Table 5.

The obtained results demonstrate the following information:

-

(1)

The causes of the presence of CT saturation severity are as follows:

-

a.

Increase of CT secondary burden (Rb),

-

b.

Increase of CT primary fault current (due to a reduction in the fault resistance, Rf),

-

c.

Increase of asymmetry in the primary fault current (due to the presence of DC components), and

-

d.

Low current transformer ratio (CTR).

-

a.

-

(2)

The proposed relay of the adaptive percentage differential type has some immunity to its malfunction in the case of severe external faults (with/without CT saturation extent and DC component content) because its operating characteristic requires a substantial ratio of operating current to restraining current.

-

(3)

In conventional differential relays, the presence of harmonics (as a result of DC components, CT saturation, or both together) may delay or prevent operation in the event of the severe internal faults. It is customary to include a high-set, unrestrained overcurrent unit in these relays. The present method addresses this issue.

Protection scheme assessment

Protection characteristics evaluation

In this study, the scenarios of internal and external faults were 1401 and 1023, respectively. There were 1400 trips in total, of which 4.0 were incorrect. Out of all scenarios, the algorithm failed to trip in 5.0 instances. The algorithm was restrained 41.0 times without any malfunctions when the system was operating normally. Table 4 illustrates the estimated dependability (DR), security (SR), reliability (RR), and accuracy (AR) of the algorithm under the influence of disparity of internal and external faults (encompassing three line, double line, double line-to-ground, and single line-to-ground faults with/without arc resistances, as well as the error of current transformers)39,40,41,42,43,44,45. The table demonstrates that the estimated values of DR, SR, RR, and AR are greater than 99.40%.

Protection scheme features

The main achievements of the adaptive differential protection are enumerated as follows:

-

(1)

It is suitable for application in digital relays,

-

(2)

It can be implemented simply because it utilizes the simplest technique of signal processing compared to the other existing schemes,

-

(3)

It is secure to the external faults accompanied by light/heavy CT saturation,

-

(4)

It has an adequate stable response for varying operating and fault conditions,

-

(5)

It has a fast response, as the operating time taken by this method is a sub-cycle,

-

(6)

It is effective, accurate and reliable,

-

(7)

It can operate online for all voltage levels of traditional and smart grids,

-

(8)

It can be used for protecting different power system elements (such as synchronous generators, power transformers, busbars, and short transmission lines),

-

(9)

It is able to apply various sizes of moving data windows for signal processing; thus, the relay operation speed can be controlled,

-

(10)

It can use various slopes criteria to execute the concept of adaptive differential relay characteristics,

-

(11)

It is useful to detect the saturated current signals, assess the severity level of CT saturation, evaluate the content of DC components in the fault current signals, and adapt the differential relay characteristics,

-

(12)

No need for selecting dual characteristic slopes or a fixed slope where the modified relay is provided with the adaptive characteristic slope,

-

(13)

Three-phase current measurements (for the two terminals of the protected equipment) are sufficient for processing the proposed algorithm; the specifications of power system elements and current transformers are not required,

-

(14)

The technique can be implemented practically,

-

(15)

The improved differential overcurrent technique develops various protection functions, such as current fault detector, faulty phase selection, fault classifier, fault direction discrimination, CT saturation detector, CT saturation assessment, and differential relay with adaptive tripping characteristics based on the form/ripple factors for the measured current signals to avoid the impacts of the current transformer saturation and the DC components.

Critical comparisons

Table 5 presents a comparison between the existing adaptive differential current relays (ADOCRs) based on alienation12,13 and correlation14 coefficients for current signals, and the proposed adaptive differential current relay (ADOCR) based on form/ripple factors for the current signals measured at the two terminals of the protected busbrs.

Conclusions

This paper has presented a protection algorithm for adaptive differential relay characteristics, taking into account the levels of CT saturation and DC component content of the current signals measured at the two ends of the protected equipment. The restraining factor has been adjusted online using the values of form and ripple factors calculated for the measured currents. The form and ripple factors, in addition to the three-phase directionality factors, have been used for CT saturation detection. These factors are useful for regulating a restraint signal in order to prevent the relay operation during external faults with/without CT saturation conditions and accelerate the relay operation in the case of large internal fault currents with high DC components. The developed adaptive protection includes changing the differential relay curve online using the form and ripple factors estimated for the equipment currents. As a result, it improves protection stability and security in the event of close external faults with/without CT saturation and increases protection sensitivity and dependability in the event of internal faults with high DC components. On a typical three-phase power system, the proposed technique has been examined under diverse operating and abnormal states (including fault types, fault locations, fault resistances, fault inception angles, CT ratios and burdens, and CT saturation levels). The ATP simulator has been used to simulate the power system under study with real data of its parameters, while MATLAB software has been used to process the adaptive differential protection algorithm. The simulation results have demonstrated noticeably better relay performance when compared to traditional relays that lack adaptive features. Also, the results have revealed a remarkable achievement in the security and stability of the protection scheme with an automatic resetting operation. Under the influence of the different internal and external faults, the evaluated percentages of the dependability (DR), security (SR), reliability (RR), and accuracy (AR) of the protection algorithm surpass 99.40%. Besides, it is a proper solution for avoiding a relay operation delay in the event of severe internal faults because of the harmonic content (resulting from the DC components or the CT saturation extent) inserted in the fault currents. Additionally, it can be used to protect different power system components with different voltage and power ratings in both conventional and smart grids. Also, the speed of the relay operation can be adjusted by altering the size of the data set, which can be selected within a single cycle. In the suggested approach method, the window length has been the primary determinant of the total post-fault data duration needed to detect a fault. The algorithm has required approximately 10 ms of the current signal following the fault inception time to make a reliable detection decision. Consequently, the proposed technique has a response time of approximately 10 ms in the case of internal faults. This time is suitable for avoiding the operation of the proposed scheme in the situation of non-fault or external fault disturbances. Therefore, it provides a quick response time to avoid the probability of CT saturation presence and its detrimental consequences.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Jena, S. & Bhalja, B. R. Sampled value-based bus zone protection scheme with dq-components. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 14(20), 4520–4528 (2020).

Wu, H., Dong, X. & Wang, Q. New principle of busbar protection based on a fundamental frequency polarity comparison. PLoS ONE 14(3), e0213308 (2019).

Jena, S. & Bhalja, B. R. Initial travelling wavefront-based bus zone protection scheme. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 13(15), 3216–3229 (2019).

Hossain, M., Leevongwat, I. & Rastgoufard, P. Design and testing of a bus differential protection scheme using partial operating current (POC) algorithm. Electr. Power Syst. 157, 29–38 (2018).

Hossain, M., Leevongwat, I. & Rastgoufard, P. Partial operating current characteristics to discriminate internal and external faults of differential protection zone. IET Gener. Transm.Distrib. 12(2), 379–387 (2018).

Qais, M., Khaled, U. & Alghuwainem, S. Improved differential relay for busbar protection scheme with saturated current transformers based on second order harmonics. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 30(4), 320–329 (2018).

Jena, S. & Bhalja, B. R. Numerical busbar differential protection using generalized alpha plane. IET Gen. Trans Dis. 12, 227–234 (2018).

Gil, M. & Abdoos, A. A. Intelligent busbar protection scheme based on combination of support vector machine and S-transform. IET Gen. Trans. Dis. 11, 2056–2064 (2017).

Ristanovic, D. et al. Bus differential protection in industrial systems with generators connected directly to the main distribution bus. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 52(4), 3574–3583 (2016).

Chothani, N. G. & Bhalja, B. R. A new algorithm for busbar fault zone identification using relevance vector machine. Elect. Power Compon. Syst. 44, 193–205 (2016).

Song, S. & Zou, G. B. A novel busbar protection method based on polarity comparison of superimposed current. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 30, 1914–1922 (2015).

Allah, R. A. Adaptive busbar differential relaying scheme during saturation period of current transformers based on alienation concept. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 10(15), 3803–3815 (2016).

R. Abd Allah, 2016 “Adaptive relay scheme with dual protection techniques based on differential and alienation principles”, International Organization of Scientific Research-Journal of Electronics and Electrical Engineering (IOSR-JEEE), E-ISSN: 2278–1676, p-ISSN: 2320–3331 Vol. 11(1) IV 33–56.

Abd Allah, R., Moussa, S., Shehab-Eldin, E. H. & Hamed, M. N. G. Adaptive busbar differential protection based on current transformer saturation degrees. Eng. Res. J. (ERJ) 33(3), 227–232 (2010).

Oliveira, M. O., Bretas, A. S. & Ferreira, G. D. Adaptive differential protection of three-phase power transformers based on transient signal analysis. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 57, 366–374 (2014).

An, W. et al. An adaptive differential protection and fast auto-closing system for 10 kV distribution Networks Based on 4G LTE Wireless Communication. Future Internet 12(1), 2 (2020).

Sarangi, S. & Pradhan, A. K. Adaptive α-plane line differential protection. Int. J. Inst Eng. Technol. 11(10), 2468–2477 (2017).

Lin, H. et al. Adaptive protection combined with machine learning for microgrids. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 13(6), 770–779 (2019).

Muda, H. & Jena, P. Superimposed adaptive sequence current based microgrid protection: A new technique. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 32(2), 757–767 (2017).

Bukhari, S. et al. A protection scheme for microgrid with multiple distributed generations using super imposed reactive energy. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 92, 156–166 (2017).

Shuanghui, Wu. An adaptive limited wide area differential protection for power grid with micro sources. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2(21), 1–9 (2017).

Ahmad, A., Othman, M. L., Zainab, K. K. & Hizam, H. Adaptive ANN based differential protective relay for reliable power transformer protection operation during energisation. IAES Int. J. Artif. Intell. 8(4), 307–316 (2019).

Dr. O. V. Ganana Swathika, S. Angalaeswari, V. Anantha Krishnan, Dr. K. Jamunaa , Dr. J.L. Febin Daya: “Fuzzy decision and graph algorithms aided adaptive protection of microgrid”, 1st International Conference on Power Engineering, Computing and Control, PECCON-2017, 2- 4 March 2017, VIT University, Chennai Campus, Energy Procedia 117, 2017, pp. 1078–1084.

Panahi, M. S. P., Azarakhsh, J. & Raisi, Z. A novel method in differential protection of power transformer using wavelet transform and correlation factor analysis. Bull. Soc. Roy. Sci. Liège 85, 1119–1135 (2016).

Seyedi, H. & Asghari Govar, S. Adaptive CWT-based transmission line differential protection scheme considering cross-country faults and CT saturation. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib 10(9), 2035–2041 (2016).

Elbana, M. S., Abbasy, N., Meghed, A. & Shaker, N. µPMU-based smart adaptive protection scheme for microgrids. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 7(4), 887–898 (2019).

Shah, A. M. A new adaptive differential protection scheme for tap changing power transformer. Int. J. Emerg. Electr. Power Syst. 16(4), 339–348 (2015).

Manufacture’s Catalogue of the Siemens SIP: “Protection, control, measurement, and automation functions”, SIPROTEC 4 – Devices, Siemens SIP · Edition No. 8/ 8.1, Chapter 9: Busbar Differential Protection/7SS52, Sep 4, 2020.

Mahmoud, R. A., Ghaly, K. G. & Hasan, S. A. Adaptive overcurrent protection considering fault current limiters effect. Int. J. Sci. Rep. 15, 20146. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05135-5 (2025).

Mahmoud, R. A. & Malik, O. P. Adaptive overcurrent relay (AOCR) based on Fano Factors of current signals. IET J. Eng. 2023(4), e12267. https://doi.org/10.1049/tje2.12267 (2023).

Sadeghi, S., Naghshbandy, A. H., Moradi, P. & Bagheri, A. Optimal adaptive coordination of overcurrent relays in power systems protection using a new hybrid metaheuristic algorithm. IET Renew. Power Gener. 18, 1948–1971. https://doi.org/10.1049/rpg2.13041 (2024).