Abstract

Understanding the rheological behavior and thermal stability of hybrid polymer-nanoparticle solutions is crucial for designing enhanced oil recovery (EOR) processes under reservoir conditions. The graphene oxide (GO)-hydrolyzed polyacrylamide (HPAM) hybrid has recently emerged as a promising approach, drawing significant attention for its potential to improve EOR efficiency. This study evaluates the impact of polymer concentration, content of GO nanoparticles and ionic strength on the hybrid solution’s performance through rheological measurements, long-term thermal stability tests, and ANOVA statistical analyses. Using a 2k factorial design and ANOVA, polymer concentration in the range of 1000–1500 ppm was identified as the primary factor, accounting for 58.34% contribution on the viscosity of hybrid solution, followed by divalent ion (18%), salinity (9%), and GO (5%). Accordingly, the Carreau rheological model was used to fit the rheological behavior of the hybrid solution. The hybrid formulation with 300 ppm GO retained 78% of its initial viscosity after 28 days at 80 °C, compared to lower retention for other formulations, highlighting the role of GO nanoparticles in improving polymer thermal stability. These findings advance the understanding of hybrid polymer-nanoparticle systems, highlight the specific role of GO nanoparticles to increase polymer performance, and provide valuable insights for designing the GO-polymer hybrid method for EOR purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the common enhanced oil recovery (EOR) methods is polymer flooding1,2. During this process, adding polymer to the injected water increases its viscosity, thus significantly improving the mobility ratio between oil and water3,4. This improvement of the mobility ratio enables a potential improvement in achieving better sweep efficiency coupled with higher oil recovery. By all established standards at the field scale, polymer flooding has secured a significant position in the petroleum industry. This technique typically yields over 20% higher recovery than waterflooding by optimizing fluid properties. Also, core flooding experiments showed that, for an applied process at the right time with the right polymer molecular weight and concentration, the oil recovery factor could be more than 20% higher than conventional water flooding5. In recent decades, owing to the declining discoveries of oil reservoirs, increase in crude oil prices, advances in technology, and economical preparation of polymers compared with other chemical EOR methods, increasing attention has been directed toward applying polymer flooding EOR method6,7.

In polymer flooding operations, different types of polymer are used; although synthetic polymers have shown promising results8,9,10so that the hydrolyzed polyacrylamide (HPAM) remains the most widely used polymer in the petroleum industry11. These polymers have a coil-like structure, and hydrolysis imparts their distinctive properties. The viscosity of HPAM increases due to the unfolding of the coiled polymer in a long chain through the repulsion of similar charges. Normally, the degree of hydrolysis for these kinds of polymers varies from 5 to 35%. Beyond the optimum degree of hydrolysis, the polymer chains re-coil, resulting in a viscosity loss12. Compared with natural polymers, synthetic polymers possess good thermal stabilities and resistivities to microbial environments13. However, applying HPAM polymers in general is also facing several challenges. According to previous studies, high salinity increases the interaction between polymer molecules and ions, deforming the polymer molecules, which may reduce the viscosity of polymer solution1. More precisely, in ionic solutions, charged molecules are surrounded by ions of opposite charge; they develop an attractive force between them, establishing a double electric layer. The functional groups of the HPAM molecules are negatively charged and interact in high-salinity solutions with cations present in the solution. These interactions decrease the thickness of the electric double layer, leading to the aggregation of polymer molecules, which reduces the viscosity of the solutio14. Temperature is another critical factor influencing polymer flooding performance. In general, an increase in temperature reduces the viscosity of the polymer solution, thus decreasing the efficiency of polymer flooding. HPAM, for example, is particularly stable at low temperatures, but at high temperatures, it undergoes both viscosity reduction and intensified hydrolysis. Such changes can lead to structural alterations in the polymer molecules, reducing their effectiveness in EOR15. Even without precipitation, the interactions between cations and the carboxyl group of the HPAM polymer can lead to decreased viscosity. Moreover, an increase in temperature raises the degree of hydrolysis, altering the polymer solution’s properties, such as rheological behavior and stability16. Previous studies have shown that HPAM polymer solution could exhibit pseudoplastic behavior under shear stress, meaning their viscosity decreases as shear stress increases17. During the polymer flooding process, polymer solution may experience shearing as it passes through pores, pumps, valves, and chokes, leading to a reduction in its viscosity. Such viscosity reduction could negatively influence the polymer performance for the EOR purposes18. The pH of the solution also significantly affects the viscosity of polymer flooding. A decrease in pH leads to protonation of polymer molecules and viscosity reduction16,19,20. Conversely, an increase in pH can raise viscosity, as initial polymer hydrolysis may occur. pH influences viscosity through two competing mechanisms. The salt effect lowers viscosity by reducing electrostatic repulsion between polymer chains, whereas hydrolysis raises viscosity by generating additional charged groups along the polymer backbone. The resulting viscosity depends on which of these effects prevails17. In addition to pH, impurities, and contaminants can also negatively impact the rheological properties of polymers21. Contaminants such as oxygen and iron typically lead to oxidation and degradation of the polymer22. The stability of the polymer solution is a variable that depends on the contact time between the solution and the reservoir. Long-term stability needs to be evaluated based on the time required for oil recovery. If the solution’s stability is shorter than the oil recovery time, the polymer will lose its properties in the porous environment, reducing the efficiency of the process23.

To address the challenges in polymer flooding, several methods have been proposed, including the synthesis of new polymers, the structural combination of polymers and nanoparticles (NPs), and the hybridization of polymers with NPs to enhance polymer solutions. As mentioned, one approach to improve polymer performance under harsh conditions is the synthesis of new polymers with enhanced thermal stability and chemical resistance. These polymers can enhance resistance to salinity, temperature, and other environmental conditions in reservoirs by adding specific functional groups or modifying the molecular structure. Such structural changes could increase polymer stability and improve its rheological properties under varying reservoir conditions24. The structural combination of polymers and the production of new resistant polymers involves adding functional groups such as vinyl pyrrolidone, NPs, and other functional groups to the polymer structure. Despite successes in this area, previous studies have shown that some new salinity-resistant polymers exhibit suboptimal performance, while others are not cost-effective7. Finally, hybridizing polymers with NPs is another effective method in polymer flooding. In this approach, polymer solutions are enhanced with NPs to improve polymer properties and take advantage of the unique characteristics of NPs. Adding NPs to a polymer solution in a hybrid form is a simpler process compared to the structural combination of polymers, as it involves fewer steps and reduced complexity. NPs have unique properties, including small size, larger surface area to volume ratio, and enhanced thermal and mechanical properties25,26,27. Previous studies have reported that adding NPs to polymer solutions could improve polymer performance by enhancing viscosity, rheological behavior, chemical resistance, and thermal stability28,29,30,31. It had been also reported that, in addition to enhancing the performance of polymer solution, the interaction between the rock and fluid is improved, reducing polymer adsorption on the rock surface and thus improving the efficiency of polymer flooding32,33. A diverse array of NPs, such as metallic, clay, and carbon-based NPs, including graphene oxide (GO) as a novel nanoparticle, has been utilized to enhance synergy and improve the properties of polymers4,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. GO is recognized for its ability to shift rock wettability from oil-wet to water-wet, improving oil displacement and recovery efficiency43,44,45,46. Also, reductions in interfacial tension (IFT) have been observed at low concentrations, enhancing oil displacement efficiency while minimizing material usage43,44. Additionally, GO has been shown to optimize mobility ratio and suppress viscous fingering during oil recovery processes47. For instance, viscosity reductions of 20–65% in heavy asphaltene-rich oil were achieved using GO, outperforming other NPs and offering cost-effective advantages48. In micro-model flooding experiments, GO nanosheets increased viscosity by 34% at 800 ppm and lowered IFT to 19.4 mN/m, resulting in a 28% higher oil recovery compared to brine and extending breakthrough time to 98 min47. Recent experimental work demonstrated that injecting low-concentration GO nanofluid (100 ppm) into porous media enhances oil recovery by approximately 10% on top of conventional water flooding, driven by improved pore-scale oil sweeping, emulsion formation, and mobilization of trapped oil, underscoring GO’s potential to address low-production challenges in complex reservoirs49. Previous studies have shown that when integrated with polymers, GO’s performance could be amplified. For instance, the addition of 0.2 wt% surface-modified GO to polymer solution was found to enhance oil recovery by 8%, attributed to improved dispersibility50. In core-flooding tests, the HPAM–graphene oxide hybrid enhanced key fluid properties, including interfacial tension, wettability, and viscosity. These improvements led to a notable increase in oil recovery compared to pure HPAM, primarily due to the amphiphilic characteristics of graphene oxide that promote better interaction at the oil–water interface51.The combined effects of GO and HPAM were examined using coreflooding experiments and CFD modeling. The results clearly demonstrate how their interaction can alter wettability and reduce interfacial tension, ultimately enhancing oil recovery52.

Advancing the progress in polymer flooding techniques, this study examines the synergistic effects of hybrid HPAM-GO solutions for EOR purposes, particularly under harsh reservoir conditions (80 ̊C and high salinity). It investigates the impact of polymer concentration, GO content and ionic strength (salinity and divalent ion) on the rheological properties and thermal stability of these hybrid solutions. Through rheological and thermal stability analyses, this research addresses key gap in the design of HPAM-GO hybrid systems. Therefore, an experimental design was implemented, and the results were subjected to statistical analysis. This study not only advances the development of more effective Polymer EOR methods but also provides key insights into the performance of the hybrid polymer- nanoparticle solution, establishing the basis for the detailed methodology.

Materials

The Table 1 details the materials utilized in this study, including their sources and specific roles. Each material is listed with its supplier, description, and specific role in the synthesis of GO, as well as in the preparation of polymer, hybrid, and brine solutions.

Methods

This section details the experimental design and methodologies employed in this study. A comprehensive overview of the experimental workflow, from material synthesis to data analysis, is provided in Fig. 1, which illustrates the key procedural steps.

Experimental design and statistical analysis

In current study the effects of polymer concentration, GO concentration, salinity (NaCl), and presence of divalent ions (Mg2+) on rheological behaviour was assessed using a 2k full factorial design. This approach allows for efficient investigation of factor interactions, making it ideal for experiments involving multiple variables. A constant ionic strength (I) was maintained to isolate the effects of the factors. The ionic strength of each solution was obtained using the following expression:

where Ci is the molar concentration of ion i (mol/L), zi is its charge number, and I is the ionic strength (eq/L). While variations in specific ion concentrations were considered, a constant ionic strength levels for the different salinity conditions were maintained to isolate the effects of the factors in our experimental design. This consistency in ionic strength was achieved by carefully adjusting the balance of ions present in the solution. For example, in the high salinity condition with no Mg²⁺, the concentrations of Na⁺ and Cl⁻ were calculated to fulfill the target ionic strength. Conversely, for the high salinity condition with the presence of Mg²⁺, the concentration of Mg²⁺ was increased, and the concentration of Na⁺ was proportionally lowered to maintain the same overall ionic strength.

Minitab version 21 and Python’s Statsmodels module were used for statistical analysis. The experimental design is outlined in Table 2. The samples in this study were labeled using a coded naming system that represents the levels of the key factors in the experimental design. The first letter represents polymer concentration, the second letter indicates the GO concentration, the third denotes salinity, and the final letter indicates the presence or absence of divalent ions. For instance, a sample labeled “HLLP” corresponds to high polymer concentration, low GO concentration, low salinity, and the absence of Mg2+, while “LHLA” corresponds to low polymer concentration, high GO concentration, low salinity, and the absence of Mg2+. It is worth mentioning that the ‘Sea water (H)’ level (high salinity) in our experimental design had an ionic strength of 1.6 eq/L, while the ‘0.1 Sea water (L)’ level (low salinity) was prepared to represent an ionic strength of 0.16 eq/L, which is one-tenth of the high salinity condition. Given this experimental design, 16 unique experiments were conducted, accounting for all possible combinations of factor levels.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to evaluate the experimental results. ANOVA is a key statistical method used to identify significant differences between group means and assess variability within and between groups. It helps uncover patterns and relationships in data, guiding decision-making and hypothesis testing. Key metrics include the p-value, which indicates the likelihood of differences occurring by chance (typically lower than threshold of 0.05 is identified as statistically significant factor), the F-statistic, which measures variability between groups, and effect size, which quantifies the magnitude of differences. These metrics collectively assess the influence of each factor on the observed variability.

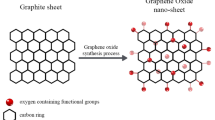

Graphene oxide synthesis and solution Preparation

The GO used in this study was prepared through a multi-stage process involving chemical exfoliation and oxidation, building upon methodologies detailed in our previous work53,54. Initially, graphite underwent thermal expansion at high temperature conditions (e.g., 900 °C) for a short duration, which induced an increase in its inter-sheet spacing. This expanded graphite was then subjected to an oxidation phase, typically involving a mixture of potassium permanganate and sulfuric acid, with controlled temperature conditions (e.g., mixing in an ice bath followed by stirring at 40 °C for two hours). A subsequent modification step involved treating the resultant paste-like liquid with cold water and hydrogen peroxide solution. For purification, the mixture was rigorously washed multiple times with sodium hydroxide and subjected to high-speed centrifugation. The purified graphite oxide was then exfoliated using a high-shear homogenizer to yield smaller GO particles. Finally, the GO nanosheets were dispersed and stabilized using probe and bath sonication to ensure a uniform dispersion.

For the preparation of the hybrid solution, a polymer solution was first prepared and allowed to rest in a controlled environment to ensure stability. The GO dispersion was subsequently added dropwise into the polymer solution under continuous stirring. Following the formation of the initial hybrid solution, it was mixed with a pre-prepared brine solution and stirred for an additional period. Comprehensive details on the synthesis and characterization of GO, as well as the preparation of the hybrid solution, are available in our previous publications53,54.

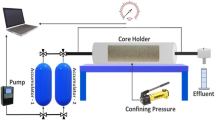

Rheology measurements

The rheological properties of the prepared samples were measured using an MCR300 SN634038 rheometer (Anton Paar, Austria), which enables precise control of shear rate and stress. All measurements were conducted at a constant temperature of 80 °C, maintained using a temperature control system to ensure consistent experimental conditions.

Carreau rheological model

The Carreau model is extensively applied in petroleum engineering to describe the rheological behavior of polymer solutions relevant to EOR. This model reliably captures viscosity variations over a broad shear rate range, encompassing both the low-shear Newtonian plateau and the shear-thinning region characteristic of pseudoplastic fluids. In addition, the model parameters (e.g., zero-shear viscosity, infinite-shear viscosity, relaxation time) possess clear physical significance, enabling quantitative interpretation of flow properties under reservoir conditions. These features collectively support its suitability for predicting the performance of polymer solutions in porous media during polymer flooding operations55. The Carreau model is mathematically expressed as follows56:

In this equation, µ represents the viscosity, with the subscript 0 indicating viscosity at zero shear rate and ∞ representing viscosity at infinite shear rate. \(\:\dot{{\upgamma\:}}\) denotes the shear rate, while n and λ are the power-law index and relaxation time, respectively. In the current study, this model is applied to fit the rheological data of the samples.

Long-term thermal stability analysis

The long-term thermal stability of the hybrid solution was also assessed. The selected samples were stored at a constant temperature of 80 °C, and viscosity measurements were taken on days 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 to examine the stability and retention of rheological properties over time. The data were analyzed to evaluate the degradation or stabilization trend of the hybrid solution under prolonged thermal exposure. The viscosity retention (VR), defined below equation, was used for analyzing the change in viscosity of the samples by time:

In this equation, µ and µ0 represent the viscosity at each time point and the initial viscosity, respectively.

Results and discussion

Investigating the effect of various parameters on the viscosity of the hybrid solution

Figure 2 presents the viscosity profiles of the 16 hybrid solutions as a function of shear rate at 80 °C. The plots are organized to highlight the influence of varying parameters. Figure 2a and c compare viscosity curves for solutions with high polymer concentrations, while Fig. 2b and d show those with low polymer concentrations, considering variations in GO concentration, salinity, and the presence of divalent ions.

Across all solutions, a general trend of shear-thinning behavior (pseudoplasticity) is observed, where viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate. Differences in the magnitude of viscosity and the degree of shear-thinning can be observed across the different plots, suggesting that the specific combination of polymer concentration, GO content, salinity, and divalent ions influences the rheological properties of the hybrid solutions. A more detailed analysis of these effects will be presented in the following sections. To better understand the effects of different factors, the viscosity of the hybrid solution at a shear rate of 10 s⁻¹ (which corresponds to the shear rate typically found in high permeability oil reservoirs) was investigated. Figure 3 illustrates the viscosity of various solutions at this shear rate value.

Figure 3 clearly shows that as the polymer concentration decreases, the viscosity value decreases, with the eight graphs on the right representing low concentration and those on the left representing high concentration. Since the viscosity values were obtained at a shear stress of 10 s⁻¹, an ANOVA analysis was performed on the viscosity results at this shear rate, and the results are presented in Table 3. Figure 4 also depicts the effect of all parameters on viscosity.

001 001q

The ANOVA analysis identified polymer concentration as the most significant factor influencing viscosity, accounting for 58.34% of the total effects. With an F-value of 1323.61 and a p-value of 0.0003, this substantial effect is attributed to the polymers’ ability to enhance viscosity through chain entanglement and hydrodynamic interactions57,58. Higher polymer concentrations increase intermolecular interactions, forming a more entangled network that resists flow and increases viscosity59. Moreover, polymer chains can adopt various configurations, such as coiled or stretched forms, which significantly influence the rheological behavior of the solution60. The increased steric hindrance at higher concentrations further impedes flow, leading to non-Newtonian behavior, typically observed in polymer solutions61. Figure 4a shows the effect of polymer concentration on viscosity.

As shown, the presence of Mg2+ significantly influenced the viscosity, with an F-value of 402.91 and a p-value of 0.0006, accounting for 17.76% of the variation. This effect is illustrated in Fig. 4d. Mg2+, with their double positive charge, can form strong bonds with the carboxyl groups on polymer chains, causing conformational changes and twisting. This ultimately leads to a reduction in hydrodynamic volume and viscosity62,63. However, Mg2+ can also positively affect viscosity by forming ionic bridges between GO NPs and polymer molecules64. Considering these phenomena and the results, it can be concluded that magnesium’s effect is negative in current conditions.

Salinity showed a notable negative effect on viscosity, with an F-value of 211.31 and a p-value of 0.0003, accounting for 9.31% of the variation. The presence of salts can influence viscosity by altering the ionic environment of the polymer-nanoparticle hybrid. High salinity can also screen electrostatic charges on polymer chains, which causes their twisting and a reduction in hydrodynamic volume65. This results in a decrease in viscosity (as seen in Fig. 4c). Additionally, salts can disrupt hydrogen bonds between GO and polymer chains, resulting in reduced viscosity.

Similarly, GO concentration had a significant effect on viscosity, with an F-value of 116.19 and a p-value of 0.0001, accounting for 5.12% of the variation. The unique two-dimensional structure of GO can notably influence viscosity by promoting the formation of a hybrid network within the polymer matrix. These GO NPs bind to polymer chains to form a hybrid network that increases viscosity53. This interaction is due to strong van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonding between the functional groups on the GO surface and the polymer chains. On a molecular level, GO NPs act as fillers, enhancing the solution’s resistance to flow66. The effect GO concentration on viscosity is shown in Fig. 4b.

Significant interactions with notable effects were observed in the ANOVA analysis, as shown in Fig. 5. The interaction between polymer concentration and salinity (as seen in Fig. 5a) was significant, with an F-value of 23.37 and a p-value of 0.0474, accounting for 1.03% of the variation. This indicates that the effect of polymer concentration on viscosity is influenced by the salinity level, where increasing salinity can neutralize the viscosity-enhancing effects of polymer chains. Additionally, the interaction between polymer concentration and Mg2+ was significant, with an F-value of 140.89 and a p-value of 0.0001, contributing to 6.21% of the variation. Figure 5b illustrates the interaction plot between polymer concentration and Mg2+. The significance of the interaction between polymer and salinity highlights the role of Mg2+ in affecting the viscosity of the hybrid. The combination of polymer and magnesium creates a weaker network due to surface charge neutralization and changes in the polymer structure. Moreover, this effect is more pronounced at higher polymer concentrations, likely due to increased interactions between Mg2+ and polymer molecules. As the polymer concentration increases, the number of interactions between magnesium and polymer molecules increases, altering the polymer chain structure and thereby reducing the viscosity of the hybrid solution.

Considering these two interactions, it is evident that the effect of Mg2+ on viscosity reduction is significantly more pronounced than that of salinity, particularly when considering the concentration of magnesium. The interaction between polymer concentration and Mg2+, with a higher F-value and a larger contribution to the variation (6.21%), underscores the substantial impact of magnesium on the hybrid solution’s viscosity. This suggests that Mg2+ are critical in altering the polymer structure and weakening the network, especially at higher polymer concentrations. In contrast, the interaction with salinity, while still significant, has a comparatively lower effect, indicating that magnesium’s influence on viscosity reduction is more dominant considering its low concentration compared with salinity.

The interaction between GO concentration and salinity (showed in Fig. 5 d) also demonstrated a significant effect, with an F-value of 9.11 and a p-value of 0.0295, accounting for 0.40% of the variation. This suggests that salinity subtly affects the contribution of GO to viscosity, where the presence of salts may reduce effective interactions between GO and polymer chains, consequently decreasing the overall viscosity enhancement. Finally, the ANOVA results indicate that the interaction between salinity and Mg2+ was significant, with an F-value of 33.34 and a p-value of 0.0022, contributing to 1.47% of the variation. As observed in Fig. 5c, both factors have a negative effect on the viscosity of the hybrid solution, and their interaction suggests that magnesium can modulate the impact of salinity on viscosity. Notably, at lower salinity levels, the presence of Mg2+ has a stronger negative effect than at higher salinity levels. This can be attributed to the higher ionic density and charge of Mg2+ compared to sodium ions (present in saline water), which have a greater influence on the bonds in the system.

Analysis of n and λ indices in the Carreau model

The Carreau model was used to assess the impact of the studied parameters on shear and viscoelastic behavior. In this process, viscosity data versus shear rate (Fig. 2) were fitted to the Carreau model, and the model provided an excellent fit to our data, with an average R² value of 0.9794. The parameters n and λ, which characterize shear behavior and relaxation time, respectively, were determined. ANOVA analysis was then performed on these parameters. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 4.

The ANOVA analysis of relaxation time (λ) and shear behavior (n) within the Carreau model offers a comprehensive evaluation of the effects of polymer concentration, GO concentration, salinity, and magnesium ion presence on the rheological properties of the hybrid solution. The results for relaxation time indicate that neither the main effects nor the interactions were statistically significant (all p-values ≥ 0.05), as evidenced by the high p-values for all factors. These findings suggest that relaxation time, a viscoelastic property, remains unaffected by variations in these parameters under the experimental conditions. Similarly, the analysis of the shear behavior parameter (n) demonstrated that the studied factors have minimal influence on shear behavior. Although salinity’s effect on ‘n’ (p-value = 0.069) approached statistical significance, it was not below the 0.05 threshold and thus not considered substantial enough to cause a meaningful change. The absence of other statistically significant interactions (all p-values ≥ 0.05) further reinforces the notion that the combined effects of these parameters do not significantly alter the rheological behavior. Overall, the results indicate that the relaxation time and shear behavior of the hybrid solution remain stable, even with varying polymer and GO levels, salinity, and magnesium ion presence. This highlights the stability of its rheological properties under current experimental conditions.

Long-term thermal analysis

In polymer flooding processes, the polymer must maintain stability under harsh reservoir conditions over extended periods. Polymer aging under these demanding conditions results in viscosity reduction, which consequently causes issues for EOR67. In the previous section, the effects of various parameters on rheological behavior were discussed, and the viscosity values for all samples at a shear rate of 10 s−1 were reported. As demonstrated, the HHLA sample exhibited the highest viscosity. Therefore, this section analyzes the long-term thermal stability and examines the impact of nanoparticle concentration, focusing on HHLA—the sample exhibiting the highest viscosity.

Additionally, two other samples, HLLA and HHLA no GO (which has a composition similar to HHLA but without NPs), are used for comparison. HHLA no GO serves as the baseline here. The results of thermal stability tests are presented in Fig. 6. As shown in Fig. 6, the HHLA sample, which contains polymer at a concentration of 1500 ppm, GO at 300 ppm, salinity at 4549 ppm, and no Mg2+, demonstrated the highest thermal stability. After 28 days, the viscosity reduction was approximately 22%. The high polymer concentration helped mitigate rapid thermal degradation by forming long chains and enhancing chain interactions. Additionally, the high concentration of GO NPs formed a stable three-dimensional network through hydrogen bonding with polymer chains, thereby reducing degradation and improving resistance to temperature over time68. Furthermore, low salinity reduced the detrimental effects of ions in the polymer structure, which improved viscosity retention54. The absence of Mg2+ further prevented potential polymer structure degradation through interactions with divalent ions.

In contrast, the HLLA sample, which consists of polymer at 1500 ppm, GO NPs at 100 ppm, salinity at 4549 ppm, and no Mg2+, exhibited lower thermal stability. After 28 days, the viscosity reduction was approximately 34%. In this sample, most parameters were similar to those of the HHLA sample, except for the nanoparticle concentration. The lower nanoparticle concentration diminished the ability of the three-dimensional network to inhibit polymer chain degradation effectively. For comparison, the HHLA sample without NPs (HHLA no GO) also exhibited lower stability than the other two samples. This difference emphasizes the crucial role of GO NPs in forming a hybrid polymer-nanoparticle network, establishing hydrogen bonds with polymer chains, and preventing degradation at high temperatures. Without GO, faster polymer chain degradation occurred due to the lack of stabilization of free radicals and prevention of thermal degradation. After 28 days, the viscosity was reduced by approximately 53%. As the results show (Fig. 6), the most significant viscosity drop occurred within the first three days of the experiment. In terms of viscosity drop rate, the HHLA sample, with its high concentration of GO, exhibited the lowest decrease. In contrast, the HLLA sample displayed a higher viscosity reduction, indicating greater sensitivity. The HHLA no GO sample experienced the highest drop, underscoring the impact of the absence of GO.

Conclusions

This study investigates the synergistic effects of graphene oxide (GO) and hydrolyzed polyacrylamide (HPAM) hybrid solutions for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) applications, focusing on their rheological behavior and thermal stability under reservoir conditions (80 °C and high salinity). The research examines the impact of key parameters such as polymer concentration, GO nanoparticle concentration, salinity, and divalent ions (Mg²⁺) on the viscosity and long-term stability of the hybrid solutions. Through rheological measurements, ANOVA statistical analysis, and long-term thermal stability tests, this study provides valuable insights into the design and optimization of GO-HPAM hybrid systems for EOR. The findings emphasize the importance of understanding the interactions between these parameters to enhance the efficiency and stability of polymer flooding in challenging reservoir environments. The main conclusions of this study are summarized as follows:

• The ANOVA results showed that polymer concentration (58.34% effect) was the most significant factor, followed by GO concentration (5.12%), salinity (9.31%), and divalent ions (Mg²⁺) with a 17.76% effect on viscosity variation.

-

The interaction between polymer concentration and Mg²⁺ was significant, with Mg²⁺ amplifying the negative effect on viscosity, particularly at higher polymer levels.

-

Salinity neutralized the viscosity-enhancing effects of polymers, especially on lower polymer concentration.

-

Results showed that presence of Mg2+ amplifies the effect of salinity on decreasing the viscosity of the hybrid solutions.

-

The Carreau model analysis revealed that shear behavior (n) and relaxation time (λ) remained stable across varying conditions, indicating that the studied parameters do not have significant effect on rheological behavior of hybrid solutions.

-

The HHLA sample (high polymer and GO) exhibited the best thermal stability, with only a 22% viscosity reduction after 28 days, while samples with lower or no GO showed significantly higher viscosity reductions (34% and 53%, respectively), underscoring the critical role of GO in stabilizing the hybrid solution.

-

The GO-HPAM hybrid system is a promising candidate for harsh reservoir conditions (high temperature and high salinity), where maintaining viscosity and thermal stability is critical for long-term efficiency.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

Abbreviations

- A:

-

Absence of divalent ions

- Adj:

-

Adjusted

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of Variance

- DF:

-

Degree of Freedom

- DIW:

-

Deionized Water

- EOR:

-

Enhanced Oil Recovery

- eq/L:

-

Equivalent per Liter

- F-value:

-

Statistical metric measuring variability between groups in ANOVA

- GO:

-

Graphene Oxide

- H:

-

High level in experimental design (e.g., 1500 ppm polymer, 300 ppm GO)

- HPAM:

-

Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide

- H₂O₂:

-

Hydrogen Peroxide

- H₂SO₄:

-

Sulfuric Acid

- I:

-

Ionic Strength

- IFT:

-

Interfacial Tension

- KMnO₄:

-

Potassium Permanganate

- L:

-

Low level in experimental design (e.g., 1000 ppm polymer, 100 ppm GO)

- Mg²⁺:

-

Magnesium Ion

- MgCl₂:

-

Magnesium Chloride

- MS:

-

Mean Square

- NaCl:

-

Sodium Chloride

- NaOH:

-

Sodium Hydroxide

- NPs:

-

Nanoparticles

- n:

-

Power-law index in the Carreau rheological model

- P:

-

Presence of divalent ions

- P-value:

-

Probability value indicating statistical significance

- ppm:

-

Parts per million

- SS:

-

Sum of Squares

- VR:

-

Viscosity Retention (%)

- γ:

-

Shear rate (s− 1)

- λ:

-

Relaxation time in the Carreau model (s)

- μ:

-

Viscosity (cP)

- μ:

-

Viscosity at zero shear rate (cP)

- μ:

-

Viscosity at infinite shear rate(cP)

References

Iravani, M. & Simjoo, M. Modeling of polymer associated low salinity waterflooding by fractional flow theory. J. Model. Eng. 17, 213–222 (2019).

Mousapour, M. S., Simjoo, M. & Chahardowli, M. Shaker shiran, B. Dynamics of HPAM flow and injectivity in sandstone porous media. Sci. Rep. 14, 28720 (2024).

Samanta, A., Ojha, K., Sarkar, A. & Mandal, A. Mobility control and enhanced oil recovery using partially hydrolysed polyacrylamide (PHPA). Int. J. Oil Gas Coal Technol. 6, 245–258 (2013).

Iravani, M., Simjoo, M. & Molaei, A. H. Synergistic effect of polymer and graphene oxide nanocomposite in heterogeneous layered porous media: a pore-scale EOR study. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 15, 9 (2025).

Han, B. & Lee, J. Sensitivity analysis on the design parameters of enhanced oil recovery by polymer flooding with low salinity waterflooding. in ISOPE International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference ISOPE-IISOPE, (2014).

Pope, G. A. Recent developments and remaining challenges of enhanced oil recovery. J. Pet. Technol. 63, 65–68 (2011).

Kamal, M. S., Sultan, A. S., Al-Mubaiyedh, U. A. & Hussein, I. A. Review on polymer flooding: rheology, adsorption, stability, and field applications of various polymer systems. Polym. Rev. 55, 491–530 (2015).

Salem, K. G., Tantawy, M. A., Gawish, A. A. & Gomaa, S. El-hoshoudy, A. N. Nanoparticles assisted polymer flooding: comprehensive assessment and empirical correlation. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 226, 211753 (2023).

Abd-Elaal, A. A., Tawfik, S. M., Abd-Elhamid, A. & Salem, K. G. El-hoshoudy, A. N. Experimental and theoretical investigation of cationic-based fluorescent-tagged polyacrylate copolymers for improving oil recovery. Sci. Rep. 14, 27689 (2024).

El-hoshoudy, A. N. et al. Enhanced oil recovery using polyacrylates/actf crosslinked composite: preparation, characterization and coreflood investigation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 181, 106236 (2019).

Abidin, A. Z., Puspasari, T. & Nugroho, W. A. Polymers for enhanced oil recovery technology. Procedia Chem. 4, 11–16 (2012).

Rezaei, A., Abdi-Khangah, M., Mohebbi, A., Tatar, A. & Mohammadi, A. H. Using surface modified clay nanoparticles to improve rheological behavior of hydrolized polyacrylamid (HPAM) solution for enhanced oil recovery with polymer flooding. J. Mol. Liq. 222, 1148–1156 (2016).

Scott, A. J., Romero-Zerón, L. & Penlidis, A. Evaluation Polym. Mater. Chem. Enhanced Oil Recovery Processes 8, 361–372 (2020).

Chauveteau, G. & Zaitoun, A. Basic rheological behavior of xanthan polysaccharide solutions in porous media: effects of pore size and polymer concentration. in Proceedings of the first European symposium on enhanced oil recovery, Bournemouth, England, Society of Petroleum Engineers, Richardson, TX 197–212 (1981).

Rashidi, M., Blokhus, A. M. & Skauge, A. Viscosity and retention of sulfonated polyacrylamide polymers at high temperature. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 119, 3623–3629 (2011).

Mungan, N. Rheology and adsorption of aqueous polymer solutions. J. Can. Pet. Technol. 8, 45–50 (1969).

Sheng, J. J. Modern Chemical Enhanced Oil Recovery: Theory and Practice (Gulf Professional Publishing, 2010).

Lai, N., Guo, X., Zhou, N. & Xu, Q. Shear resistance properties of modified nano-SiO2/AA/AM copolymer oil displacement agent. Energies 9, 1037 (2016).

Liu, P., Mu, Z., Wang, C. & Wang, Y. Experimental study of rheological properties and oil displacement efficiency in oilfields for a synthetic hydrophobically modified polymer. Sci. Rep. 7, 8791 (2017).

Levitt, D. & Pope, G. A. Selection and screening of polymers for enhanced-oil recovery. in SPE symposium on improved oil recoverySociety of Petroleum Engineers, (2008).

Lee, K. S. Performance of a polymer flood with shear-thinning fluid in heterogeneous layered systems with crossflow. Energies 4, 1112–1128 (2011).

Caulfield, M. J., Qiao, G. G. & Solomon, D. H. Some aspects of the properties and degradation of polyacrylamides. Chem. Rev. 102, 3067–3084 (2002).

Sorbie, K. S. Polymer-improved Oil Recovery (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Khalilnezhad, A., Sahraei, E., Cortes, F. B. & Riazi, M. Encapsulation of Xanthan gum for controlled release at water producer zones of oil reservoirs. Pet Sci. Technol 43(3), 1–22 (2025).

Bera, A. & Belhaj, H. Application of nanotechnology by means of nanoparticles and nanodispersions in oil recovery-A comprehensive review. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 34, 1284–1309 (2016).

Sun, X., Zhang, Y., Chen, G. & Gai, Z. Application of nanoparticles in enhanced oil recovery: a critical review of recent progress. Energies 10, 345 (2017).

Khalilnezhad, A., Rezvani, H., Abdi, A. & Riazi, M. Chapter 8 - Hybrid thermal chemical EOR methods. in Enhanced Oil Recovery Series (eds Hemmati-Sarapardeh, A., Alamatsaz, A., Dong, M. & Li, Z.) (2023). B. T.-T. M.) 269–314 (Gulf Professional Publishing, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821933-1.00003-3.

Paul, D. R. & Robeson, L. M. Polymer nanotechnology: nanocomposites. Polym. (Guildf). 49, 3187–3204 (2008).

Pavlidou, S. & Papaspyrides, C. D. A review on polymer–layered silicate nanocomposites. Prog Polym. Sci. 33, 1119–1198 (2008).

Li, S., Meng Lin, M., Toprak, M. S., Kim, D. K. & Muhammed, M. Nanocomposites of polymer and inorganic nanoparticles for optical and magnetic applications. Nano Rev. 1, 5214 (2010).

Iravani, M., Khalilnezhad, Z. & Khalilnezhad, A. A review on application of nanoparticles for EOR purposes: history and current challenges. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 13, 959–994 (2023).

Cheraghian, G. et al. Adsorption polymer on reservoir rock and role of the nanoparticles, clay and SiO2. Int. Nano Lett. 4, 114 (2014).

Khalilinezhad, S. S., Cheraghian, G., Roayaei, E., Tabatabaee, H. & Karambeigi, M. S. Improving heavy oil recovery in the polymer flooding process by utilizing hydrophilic silica nanoparticles. Energy Sources Part. Recover Util. Environ. 39, Eff 1–10 (2017).

Nourafkan, E., Haruna, M. A., Gardy, J. & Wen, D. Improved rheological properties and stability of multiwalled carbon nanotubes/polymer in harsh environment. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 136, 47205 (2019).

Zhang, L., Tao, T. & Li, C. Formation of polymer/carbon nanotubes nano-hybrid shish–kebab via non-isothermal crystallization. Polym. (Guildf). 50, 3835–3840 (2009).

Feng, L., Xie, N. & Zhong, J. Carbon nanofibers and their composites: a review of synthesizing, properties and applications. Mater. (Basel). 7, 3919–3945 (2014).

Cheraghian, G., Shahram, S. & Nezhad, K. Effect of nanoclay on improved rheology properties of polyacrylamide solutions used in enhanced oil recovery. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13202-014-0125-y (2015).

Bahraminejad, H., Manshad, A. K., Iglauer, S. & Keshavarz, A. NEOR mechanisms and performance analysis in carbonate/sandstone rock coated microfluidic systems. Fuel 309, 122327 (2022).

Khalilnezhad, A. et al. Improved oil recovery in carbonate cores using alumina nanoparticles. Energy Fuels. 37, 11765–11775 (2023).

Rezvani, H., Khalilnejad, A. & Amir Sadeghi-Bagherabadi, A. Comparative experimental study of various metal oxide nanoparticles for the wettability alteration of carbonate rocks in EOR processes. in 80th EAGE Conference and Exhibition : Opportunities Presented by the Energy Transition 2018, 1–5 (European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers, 2018). (2018).

Khalilnejad, A., Lashkari, R., Iravani, M. & Ahmadi, O. Application of synthesized silver nanofluid for reduction of Oil-Water interfacial tension. in Saint Petersburg 2020 2020, 1–5 (European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers, (2020).

Giraldo, L. J. et al. 1 - Natural nanoclays. in Micro and Nano Technologies (eds. Mallakpour, S. & Mustansar Hussain, C. B. T.-F. N.) 3–24 (Elsevier, 2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-15894-0.00002-1

Gómez-Delgado, J. L., Rodriguez-Molina, J. J., Perez-Angulo, J. C. & Santos-Santos, N. Mejía-Ospino, E. Evaluation of the wettability alteration on sandstone rock by graphene oxide adsorption. Emergent Mater. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42247-023-00596-8 (2023).

Xuan, Y., Zhao, L., Li, D., Pang, S. & An, Y. Recent advances in the applications of graphene materials for the oil and gas industry. RSC Adv. 13, 23169–23180 (2023).

Radnia, H., Solaimany Nazar, A. R. & Rashidi, A. Experimental assessment of graphene oxide adsorption onto sandstone reservoir rocks through response surface methodology. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 80, 34–45 (2017).

Molaei, A., Iravani, M. & Simjoo, M. Enhanced oil recovery in a heterogeneous glass micro-model by application of low-concentration graphene oxide. Pet Sci. Technol. 43, 1–19 (2025).

Khoramian, R., Ramazani, S. A., Hekmatzadeh, A., Kharrat, M., Asadian, E. & R. & Graphene oxide nanosheets for oil recovery. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 5730–5742 (2019).

Elshawaf, M. Consequence of graphene oxide nanoparticles on heavy oil recovery. in Society of Petroleum Engineers - SPE Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Annual Technical Symposium and Exhibition 2018, SATS 23–26 (2018). 23–26 (2018). (2018). https://doi.org/10.2118/192245-ms

Molaei, A. H., Simjoo, M., Iravani, M. & Chahardowli, M. Experimental Insights into the EOR Potential of Graphene Oxide Nanofluid: A Micro-Scale Study. in The 12th International Chemical Engineering Congress & Exhibition (IChEC) (2023).) (2023). (2023).

Aliabadian, E. et al. Application of graphene oxide nanosheets and HPAM aqueous dispersion for improving heavy oil recovery: effect of localized functionalization. Fuel 265, 116918 (2020).

Haruna, M. A., Tangparitkul, S. & Wen, D. Dispersion of polyacrylamide and graphene oxide nano-sheets for enhanced oil recovery. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 699, 134689 (2024).

Lashari, N. et al. Synergistic effect of graphene oxide and partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide for enhanced oil recovery: merging coreflood experimental and CFD modeling approaches. J. Mol. Liq. 394, 123733 (2024).

Iravani, M., Simjoo, M., Chahardowli, M. & Moghaddam, A. R. Experimental insights into the stability of graphene oxide nanosheet and polymer hybrid coupled by ANOVA statistical analysis. Sci. Rep. 14, 18448 (2024).

Iravani, M., Simjoo, M. & Chahardowli, M. Screening key parameters affecting stability of graphene oxide and hydrolyzed polyacrylamide hybrid: relevant for EOR application. Heliyon e42875 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42875 (2025).

Zeynalli, M. et al. A comprehensive review of viscoelastic polymer flooding in sandstone and carbonate rocks. Sci. Rep. 13, 17679 (2023).

Carreau, P. J. Rheological equations from molecular network theories. J. Rheol (N Y N Y). 16, 99–127 (1972).

Pawlak, A. & Krajenta, J. Entanglements of macromolecules and their influence on rheological and mechanical properties of polymers. Molecules 29, 3410–3423 (2024).

Kulicke, W. M. & Kniewske, R. The shear viscosity dependence on concentration, molecular weight, and shear rate of polystyrene solutions. Rheol Acta. 23, 75–83 (1984).

Bai, L. et al. Experimental study and numerical simulation of polymer flooding. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Process. 18, 1–12 (2022).

Kulichikhin, V. The role of structure in polymer rheology: review. Polym. (Basel). 14, 1262 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. Properties of nanofluids and their applications in enhanced oil recovery: A comprehensive review. Energy Fuels. 34, 1202–1218 (2020).

Jahandideh, H., Ganjeh-Anzabi, P., Bryant, S. L. & Trifkovic, M. The significance of graphene Oxide-Polyacrylamide interactions on the stability and microstructure of Oil-in-Water emulsions. Langmuir 34, 12870–12881 (2018).

Mao, J. et al. Novel Hydrophobic Associating Polymer with Good Salt Tolerance. Polymers 10, (2018).

Nguyen, B. D. et al. The impact of graphene oxide particles on viscosity stabilization for diluted polymer solutions using in enhanced oil recovery at HTHP offshore reservoirs. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 6, 15012 (2014).

Gbadamosi, A. O., Junin, R. & Manan, M. A. Hybrid suspension of polymer and nanoparticles for enhanced oil recovery. In Polymer Bulletin (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-019-02713-2.

Haruna, M. A., Pervaiz, S., Hu, Z., Nourafkan, E. & Wen, D. Improved rheology and high-temperature stability of hydrolyzed polyacrylamide using graphene oxide nanosheet. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 136, 47582 (2019).

Pospı́šil, J., Horák, Z., Kruliš, Z., Nešpůrek, S. & Kuroda, S. Degradation and aging of polymer blends I. Thermomechanical and thermal degradation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 65, 405–414 (1999).

Haruna, M. A., Pervaiz, S., Hu, Z., Nourafkan, E. & Wen, D. Improved rheology and high-temperature stability of hydrolyzed polyacrylamide using graphene oxide nanosheet. J Appl. Polym. Sci 136, 47582–9 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mostafa Iravani: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization, Perform the experiments, Formal Analysis. Mohammad Simjoo: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization, Resources, Project administration. Mohammad Chahardowli: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iravani, M., Simjoo, M. & Chahardowli, M. Exploring synergistic effects of graphene oxide and hydrolyzed polyacrylamide on rheology and thermal stability relevant to enhanced oil recovery. Sci Rep 15, 27380 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13256-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13256-0