Abstract

Antenatal Care, use of skilled delivery attendants, Institutional delivery and postnatal care services are key maternal health services that can significantly reduce maternal mortality. The objective of this study was to identify spatial distribution and factors that affect full package utilization of maternal health services in Ethiopia. Sampling weights were applied, and analyses were conducted using STATA version 17. Spatial statistics, including Moran’s I and Getis-Ord Gi*, were performed in ArcGIS to assess spatial autocorrelation and identify FPMHSU clusters. SaTScan software detected purely spatial clusters. Multilevel binary logistic regression identified individual- and community-level factors. Model selection was based on a significant log-likelihood ratio test and Variables with p < 0.05 were deemed significant, with adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals quantifying associations. The prevalence of in Ethiopia was 56.96% (95% CI: 55.41%, 58.51%) and exhibited significant spatial clustering (Moran’s Index = 0.686, P < 0.001). Women aged 20–24 years [AOR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.44–0.97], high parity [AOR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.40–0.69] and urban residents [AOR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.31–0.89] reduce the outcome, while being married [AOR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.04–2.30], Muslim religion [AOR = 2.25, 95% CI: 1.45–3.48], primary education [AOR = 2.04, 95% CI: 1.65–2.52], secondary education [AOR = 2.30, 95% CI: 1.53–3.45], higher education [AOR = 6.10, 95% CI: 2.43–15.07], awareness of pregnancy complications [AOR = 3.62, 95% CI: 3.00–4.36], poorer households [AOR = 1.77, 95% CI: 1.32–2.37], middle wealth category [AOR = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.13–2.14], richer households [AOR = 2.61, 95% CI: 1.84–2.71], and the richest households [AOR = 6.70, 95% CI: 3.96–11.56] increase the outcome. This study revealed significant disparities in in Ethiopia, with spatial clustering (Moran’s I = 0.686) and hotspots in Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa, Harari, and East Gojam. Women with higher education (primary, secondary, and higher), Muslim religion, awareness of pregnancy complications, better economic status (poorer, middle, richer, and richest wealth categories), and urban residence were more likely to utilize maternal health services. Addressing these disparities is crucial for improving maternal health outcomes and ensuring equitable access.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maternal health care utilization refers to the comprehensive healthcare services provided to women from pregnancy through the postpartum period. This includes antenatal care (ANC), delivery care, and postnatal care (PNC) services1. Access to comprehensive maternal healthcare ensures early detection of complications, timely interventions, and improved health outcomes for both mothers and newborns2. However, disparities in maternal health service utilization remain a major public health challenge, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including sub-Saharan Africa3.

In 2020, nearly 800 women died every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth, equating to a maternal death approximately every two minutes. Despite a global reduction in the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) by about 34% between 2000 and 2020, the burden remains disproportionately high in low- and lower-middle-income countries, accounting for 95% of all maternal deaths4,5. However, skilled care during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period has the potential to save the lives of both women and newborns, highlighting the critical importance of improving access to maternal health services globally1,6,7,8,9,10.

In 2009, the Ethiopian government launched the Urban Health Extension Program (UHEP) to promote health equity by increasing demand for essential services through household-level health education, outreach in schools and youth centers, and improving access via referrals to health facilities. This initiative aims to bridge gaps in healthcare access and empower communities with critical health knowledge7,10. Despite national efforts to improve maternal health, only 43% of women in Ethiopia received at least four ANC visits, 48% delivered with a skilled birth attendant, and just 34% received PNC within 48 h, highlighting significant gaps in the full package of maternal health service utilization (FPMHSU)11.

In Ethiopia, limited autonomy often restricts women’s access to the full package of maternal health services, including antenatal care, skilled delivery, and postnatal care, exacerbating maternal health disparities. Addressing these barriers is critical for empowering women and enhancing maternal health outcomes nationwide12,13.

Existing research has identified several socio-demographic and economic determinants of maternal health service utilization, such as education, wealth, and residence6,7,9,10,14. However, limited studies have explored the spatial distribution and community-level factors influencing the full package of maternal health services in Ethiopia. Spatial disparities, particularly between urban and rural areas and across regions, are not well-documented. Additionally, there is a lack of integration of spatial analysis and multilevel modeling in understanding these patterns, which hinders the development of targeted and location-specific interventions.

Addressing these gaps is crucial for improving maternal health outcomes and achieving equity in healthcare access. Identifying underserved regions and understanding the drivers of low utilization can inform resource allocation, policy formulation, and the design of tailored interventions to meet the needs of Ethiopian women more effectively.

The primary aim of this study is to assess the spatial distribution and determinants of FPMHSU in Ethiopia using the 2019 Mini Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (MEDHS). By employing spatial and multilevel analytical approaches, this research seeks to identify geographic disparities and the individual-, household-, and community-level factors that influence maternal health service utilization. The findings will provide critical evidence for policymakers and stakeholders to address gaps in maternal healthcare and promote equitable access across Ethiopia.

Methods and materials

Study area and period

The study was conducted in Ethiopia, the second most populous country in sub-Saharan Africa, located in the northeastern part of the continent. Ethiopia lies between 3° and 15° north latitude and 33° and 48° east longitude. It has an estimated total population of 128,764,502, making it the 11th most populous country in the world15. The total land area is approximately 1,000,000 km2 (386,102 square miles), with a population density of 115 people per km2. Of the total population, 21.3% (24,463,423) resides in urban areas15. The study was conducted from October 2024 to December 2024.

Study design

A cross-sectional secondary data analysis was conducted using the 2019 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) dataset.

Population

Source population

All pregnant and Lactating women in Ethiopia.

Study population

All pregnant and Lactating who were found in the randomly selected enumeration areas (EAs) of Ethiopia included in the 2019 EDHS and had complete data on maternal health service utilization.

Sample size and sampling procedure

The sampling frame for the 2019 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) was derived from the enumeration areas (EAs) identified in the 2007 Ethiopian Population and Housing Census (PHC). A stratified, two-stage cluster sampling design was employed. In the first stage, 305 EAs (93 urban and 212 rural) were randomly selected from the 149,093 EAs listed in the PHC sampling frame, using probability proportional to size (PPS). In the second stage, 30 households were systematically selected from each EA using an equal-probability sampling approach. The survey collected data from a nationally representative sample of 8,885 women aged 15–49 years. Of these, 3,927 (weighted) women provided complete data relevant to the analysis of full-package maternal health service utilization (FPMHSU), drawn from nine regional states and two city administrations.

Data source and extraction

The DHS data set is publicly available for registered users. The 2019 EDHS dataset was downloaded from the DHS Program website (https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/dataset_admin). Data on maternal health service utilization and related independent variables (individual- and community-level factors) were extracted for analysis.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

This study included women aged 15–49 years who had given birth within five years prior to the 2019 EDHS survey and had complete data on maternal health service utilization.

Exclusion criteria

Women were excluded from the analysis if they had incomplete or inconsistent data on any of the key components of FPMHSU. Clusters with zero eligible respondents or clusters containing only missing values for maternal health service indicators were also excluded during data cleaning to ensure the reliability of spatial and multilevel analysis.

Variables of the study

Dependent variable

Full package maternal health service utilization: The outcome variable, Full Package Maternal Health Service Utilization was ascertained based on whether women received all four essential maternal health services:(attending at least four antenatal care visits during pregnancy, delivery assisted by a skilled birth attendant, giving birth in a healthcare facility, and receiving postnatal care within 48 h of delivery). Women who met all four criteria were coded as "1" (utilized FPMHSU), while those who missed any component were coded as "0" (did not utilize FPMHSU).

Independent variables

Individual-/Household-level variables: Maternal age, marital status, religion, educational status, wealth index, parity, preceding birth interval, contraceptive use, media exposure, sex of household head, age at first birth, told pregnancy complication, sex of child and family size.

Community-level variables: Residence (urban/rural) and region.

Operational deflations

-

Full Package Maternal Health Service Utilization (FPMHSU) refers to a woman accessing all four essential components of maternal health services1.

-

Media exposure: Cgorized as Yes of the household in the cluster had TV/ radio and No if the household in the cluster had TV/radio16.

-

Wealth Index: The wealth index in the 2019 EDHS is a composite measure of a household’s living standard and calculated using data on household assets, housing materials, and access to services. Households are ranked and divided into five groups from poorest to richest17.

Data processing and analysis

Data processing and analysis for this study involved cleaning, recoding, and weighting the data to account for sampling probabilities and non-responses. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, were computed using STATA 17, with results presented in tables, graphs, and text. Spatial analysis linked maternal health service utilization proportions to the geographic locations of survey clusters using ArcGIS. This analysis involved spatial autocorrelation with Moran’s I statistic to assess clustering, Getis-Ord Gi* for hotspot analysis, Kriging interpolation for estimating maternal health utilization in un-sampled areas, and SaTScan to identify spatial clusters.

For multilevel binary logistic regression, a two-level mixed-effects model was employed to estimate the effects of individual- and community-level factors. The model-building process included an empty model to examine clustering, adjustments for individual- and community-level factors in subsequent models, and the final combined model. Variance measures like the Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC), Median Odds Ratio (MOR), and Proportional Change in Variance (PCV) were used to assess community-level influence. Variables with p < 0.25 were considered for multivariable analysis., and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to identify associations. Model fit was assessed using log-likelihood ratio tests and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

Result

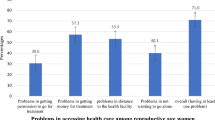

Individual level and Household level characteristics of study participants

This study analyzed data from a weighted sample of 3,927 women aged 15 to 49, of which 2,236 (56.94%, 95% CI: 55.41%, 58.51%) had utilized full package maternal health services. The average age of the respondents was 28.65 ± 0.1 years. Only one third (36%) had completed only primary education. Additionally, 2,193 (55.84%) women reported not using any contraceptive methods, and 2,176 (55.4%) hadn’t been told about pregnancy complication (Table 1).

Household level characteristics of study participants

Approximately 826 (21.03%) of the women were classified as the poorest, while 754 (19.2%) were categorized as the richest. Regarding household composition, 3,401 (86.6%) of the respondents lived in male-headed households, and 1,342 (34.17%) came from large families (Table 2).

Community level characteristics of study participants

This study included 305 clusters, with 2,900 women (73.84%) residing in rural areas. The Harari region had the lowest maternal health service utilization at 8 women (0.2%), while the Oromia region had the highest utilization, with 778 women (19.81%) (Table 3).

Spatial distribution of full package maternal health service utilization

Spatial autocorrelation analysis

At the regional level, Ethiopia showed significant spatial variations in maternal health service utilization (MHSU) rates. The spatial distribution analysis revealed statistical significance, with a Moran’s index of 0.686 and a p-value of less than 0.01 (Fig. 1).

Spatial Autocorrelation report of FPMHSU in Ethiopia 2019 EDHS. The map was created by the authors using ArcGIS version 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview). The shapefile for Ethiopia’s administrative boundaries was obtained from https://data.humdata.org/dataset/cod-ab-eth, which is freely available for public use under the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) open license.

Spatial distribution of full package maternal health service utilization

The spatial distribution of Full Package Maternal Health Service Utilization in Ethiopia exhibited significant variation across its zones. The highest utilization rates were found in Addis Ababa, Harari, Dire Dawa, EasternAfar region, Southern andEastern Amhara, Eastern Oromia region and southern parts of SNNPR, and western Benishangul Gumuz region. In contrast, southern parts of the Afar region,western parts of Amhara region, and most areas in the Somali region had lower rates of FPMHSU (Fig. 2).

Spatial distribution of FPMHSU in Ethiopia 2019 EDHS. The map was created by the authors using ArcGIS version 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview). The shapefile for Ethiopia’s administrative boundaries was obtained from https://data.humdata.org/dataset/cod-ab-eth, which is freely available for public use under the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) open license.

Local Morans I result of full package maternal health service utilization

As illustrated in the figure below, identifying significant neighborhood clustering is essential, including high clustering, low clustering, and spatial outliers (represented by red and green dots). High-High clustering refers to areas with high FPMHSU utilization surrounded by regions with similarly high utilization, while Low-Low clustering indicates areas with low prevalence surrounded by regions with similarly low prevalence. High-High clustering was observed in Addis Ababa, East Gojam, Gurage, Silte, and East Shewa parts of Ethiopia. Conversely, Low-Low clustering was found in Gamo Gofa, Wolayta, Sidama, Zone 3, and Zone 5 of the Afar region, where low utilization areas were surrounded by other low utilization areas (Fig. 3).

Local Moran I analysis of FPMHSU in Ethiopia 2019 EDHS. The map was created by the authors using ArcGIS version 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview). The shapefile for Ethiopia’s administrative boundaries was obtained from https://data.humdata.org/dataset/cod-ab-eth, which is freely available for public use under the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) open license.

Gettis-OrdGi* statistics identification of full package maternal health service utilization

Hotspot analysis identifies regions with either high or low utilization of FPMHSU. Low-risk areas, indicated by green color, were found in Dire Dawa, Harari, Addis Ababa, East Shewa, West Shewa, Gurage, and Silte parts of Ethiopia. Conversely, regions such as Somali, Sidama, Gamo Gofa, and Gedo were identified as High risk areas as indicated by red color, characterized by low utilization of FPMHSU (Fig. 4).

Gettis-OrdGi* statistics of FPMHSU in Ethiopia 2019 EDHS. The map was created by the authors using ArcGIS version 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview). The shapefile for Ethiopia’s administrative boundaries was obtained from https://data.humdata.org/dataset/cod-ab-eth, which is freely available for public use under the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) open license.

Kringing interpolation of full package maternal health service utilization

Interpolation analysis predicted high FPMHSU utilization in areas such as East Shewa, West Shewa, Addis Ababa, Harari, and Dire Dawa. In contrast, the majority of areas in the Somali region were predicted to have low utilization of FPMHSU (Fig. 5).

Kringing interpolation of FPMHSU in Ethiopia 2019 EDHS. The map was created by the authors using ArcGIS version 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview). The shapefile for Ethiopia’s administrative boundaries was obtained from https://data.humdata.org/dataset/cod-ab-eth, which is freely available for public use under the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) open license.

Spatial scan statistics of full package maternal health service utilization in Ethiopia

Spatial scan statistics are highly effective in detecting clusters, offering more reliable results compared to other methods. In 2019, this analysis identified one primary and five secondary clusters of FPMHSU in Ethiopia. The primary cluster, with a log-likelihood ratio (LLR) of 71.62 and a p-value of less than 0.0000000001, encompasses Addis Ababa, the Amhara region, Tigray, Benishangul, and zones of the Afar region. This cluster is centered at (12.985634 N, 36.239465 E), with a radius of 558.56 km and a relative risk (RR) of 21.39 (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 6).

SaTScan analysis of FPMHSU in Ethiopia based on the 2019 Mini Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. The map was created by the authors using SaTScan™ version 10.1 (https://www.satscan.org/), and ArcGIS version 10.8 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview). The shapefile for Ethiopia’s administrative boundaries was obtained from https://data.humdata.org/dataset/cod-ab-eth, which is freely available for public use under the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) open license.

Random effects

The random effects analysis revealed significant clustering in FPMHSU across communities in Ethiopia, as indicated by the intra-cluster correlation coefficient (ICC). The ICC in the empty model was 42.48%, suggesting that nearly 43% of the variation in FPMHSU could be attributed to differences between clusters or communities, highlighting the substantial role of contextual and community-level factors in the utilization of maternal health services. As individual- and community-level variables were added to the models, the ICC progressively decreased, reaching 19.99% in the final model, indicating that while predictors explained a large portion of the variation, unexplained community-level factors still played a significant role in determining FPMHSU.

The Proportional Change in Variance (PCV) showed a substantial reduction in variance from 2.43 in the empty model to 0.82 in the final model, indicating that much of the inter-community variability was explained by both individual- and community-level factors. This suggests that interventions targeting these factors could reduce disparities in maternal health service utilization. The Median Odds Ratio (MOR) in the models also reflected a decrease in cluster heterogeneity. The MOR was 4.02 in the empty model, decreasing to 2.33 in the final model, highlighting a reduction in unexplained variation with the inclusion of predictors.

Model fitness improved with the inclusion of predictors, evidenced by the log-likelihood increasing from -2238.02 in the empty model to -1878.90 in the final model. This improvement underscores the value of incorporating both individual and contextual factors to better explain and predict FPMHSU (Table 4).

Factors associated with full package maternal health service utilization (fixed‑effect)

This study identified several key factors influencing FPMHSU. Maternal age was significant, with women aged 20–24 years 35% less likely [AOR = 0.65, 95% CI (0.44–0.97)] to utilize the services compared to those aged 15–19 years. Married women were 54% more likely [AOR = 1.54, 95% CI (1.04–2.3)] to use FPMHSU than unmarried women. Muslim women being over twice as likely [AOR = 2.25, 95% CI (1.45–3.48)] to use the services compared to other religion follower women.

Women with primary education were twice as likely [AOR = 2.04, 95% CI (1.65–2.52)], and those with secondary education were 2.3 times more likely [AOR = 2.3, 95% CI (1.53–3.45)] to use the full package. Women with higher education had the highest likelihood, being six times more likely [AOR = 6.1, 95% CI (2.43–15.07)] to utilize the services. Awareness of pregnancy complications was also a key factor, with informed women 3.6 times more likely [AOR = 3.62, 95% CI (3–4.36)] to use FPMHSU.

Women having high parity 48% less likely [AOR = 0.52, 95% CI (0.4–0.69)] to use the services. Women from poorer households more likely to use the services, especially those in the richest category, who were 6.7 times more likely [AOR = 6.7, 95% CI (3.96–11.56)]. Finally, women living in rural areas were 47% less likely [AOR = 0.53, 95% CI (0.31–0.89)] to utilize FPMHSU compared to urban residents (Table 5).

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the spatial distribution and factors associated with FPMHSU in Ethiopia. The prevalence of FPMHSU was found to be 56.96% (95% CI: 55.41%, 58.51%), with its distribution exhibiting non-random patterns. Significant associations were identified with various factors, including maternal education, household wealth index, maternal age, residence, parity, religion, marital status, and awareness of pregnancy complications.

The prevalence observed in our study is slightly higher than a study done in Jima (54.4%)18, Ambo (14.2%)1 and Pooled Study of 37 Low and Middle-Income Countries (33.7%)19, but lower than a study in west Shewa (64.8%)20. Variation in these results may be difference in health system infrastructure, maternal health program implementation, community awareness and availability of integrated maternal health service7.

At the regional level, significant spatial variation in of FPMHSU was observed in Ethiopia (Moran’s I = 0.686, P valu < 0.01), consistent with studies conducted in 2016 EDHS21 and India22. Hotspot analysis of FPMHSU revealed that there were high utilization of maternal health service in Addis Ababa, Harari, Diredawa, East Shewa, Gurage and Silte. This difference may be attributed to better health system infrastructure, higher accessibility of health facilities and urbanization in these areas, which enhance service delivery and utilization21,23,24.

The study revealed that the odds of utilizing FPMHSU were lower among mothers aged 20–24, a finding consistent with other research25. This suggests that adolescent and young mothers represent a uniquely vulnerable subgroup within the broader population of women. They often face compounded challenges, including limited autonomy, reduced access to information, and financial constraints, which hinder their ability to seek comprehensive maternal healthcare26.

Education was another associated factor for FPMHSU in which educated women’s are more likely to use FPMHSU than uneducated one. This find was supported by a study done on 2011 EDHS10, Uganda9 and Nigeria8. This positive relationship may be attributed to the fact that educated women are more likely to be informed about the importance of maternal health services. They may have better access to written information and tend to adopt more modern cultural perspectives27,28.

In this study, urban residence was significantly associated with the utilization of maternal health services. This finding aligns with other studies conducted in Nigeria6 and Ethiopia10. The disparity may be attributed to the greater availability of infrastructure in urban areas, such as shorter distances to health facilities, better roads, and improved transportation options. In Ethiopia, the availability of health workers varies significantly across regions. For instance, Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa, with urban populations of 100% and 67.5% respectively, have a higher number of medical doctors compared to regions with larger rural populations. In these cities, the ratio of doctors to the population is more favorable, with one medical doctor per 3,056 people in Addis Ababa and one per 6,796 in Dire Dawa. In contrast, regions like Amhara and Oromia, where urban populations are 12.6% and 12.2% respectively, have significantly fewer medical doctors29.

This study found that household wealth status is significantly associated with the utilization of maternal health services. Women from wealthier households are more likely to use maternal health services compared to those from poorer households. This finding is consistent with other similar studies7,9,10,14,20. The correlation between wealth and service utilization can be explained by the fact that access to health services in Ethiopia largely depends on out-of-pocket payments. While services for antenatal care (ANC), delivery, and postnatal care (PNC) are exempt from fees, women are still required to pay for medications, and additional costs such as transportation can make seeking care expensive, potentially deterring women from utilizing available services30.

This study has shown that parity plays a significant role in determining maternal health service utilization, consistent with findings from studies conducted in Ethiopia10. Women with higher parity (more than two children) were less likely to use maternal health services. This could be attributed to the fact that women with more children may feel more confident in delivering at home and may lack the motivation to seek professional care. In contrast, primipara women (those with their first pregnancy) may be more likely to use maternal health services due to concerns about pregnancy complications and outcomes, stemming from the perceived risks associated with first pregnancies.

Mothers who were informed about the potential complications of pregnancy were more likely to utilize maternal health services. This finding is consistent with a national level survey conducted in Ethiopia11 and Holeta town7 The increased likelihood of service utilization can be attributed to a greater awareness of the risks associated with pregnancy, which likely leads to a heightened perception of the need for comprehensive care. Being informed about potential complications may motivate expectant mothers to seek timely medical attention to ensure their health and the health of their baby31.

Women who follow the Muslim faith were found to be more likely to utilize FPMHSU, a finding consistent with previous research10. This trend could be attributed to the structured guidance and community support often embedded within Islamic teachings, which emphasize health and well-being. In contrast, women adhering to traditional religions may have a stronger inclination toward cultural practices and beliefs that prioritize traditional healing methods over modern healthcare31,32.

The study also observed that married women are more likely to utilize FPMHSU compared to their unmarried counterparts, aligning with findings from previous studies conducted in Ethiopia10. This disparity may be explained by the social and financial support that marriage often provides. Married women are more likely to have a partner who can share the responsibilities and costs associated with seeking maternal healthcare. Additionally, spousal support may encourage joint decision-making, increasing the likelihood of timely health service utilization33.

The study’s strengths include its use of nationally representative data with a large sample size and a statistical approach that effectively addresses the data’s hierarchical structure. Additionally, the application of sampling weights ensured reliable estimates. However, the study has several limitations. The cross-sectional design prevents causation from being established between independent and dependent variables. The reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of recall bias, as respondents were asked to recall past events. Moreover, the EMDHS data, being a mini report, lacked information on some predictor variables for FPMHSU. Lastly, to maintain data confidentiality, location values were adjusted by 1–2 km in urban areas and 5 km in rural areas, which may affect the accuracy of case locations.

Conclusion and recommendations

In conclusion, this study revealed some striking differences in how Full Package Maternal Health Services are used across Ethiopia, with a significant clustering effect (Moran’s I = 0.686). Areas with high utilization were mainly found in urban and central regions like Dire Dawa, Harari, Addis Ababa, and certain parts of Shewa and Gurage zones. On the flip side, low-utilization hotspots were identified in regions such as Somali, Sidama, Gamo Gofa, and Gedo. The research found that higher maternal education, being part of the Muslim community, better economic conditions, awareness of pregnancy complications, and living in urban areas were all linked to increased service utilization. Conversely, younger women (ages 20–24), those with multiple children, and those living in rural areas tended to use these services less.

Recommendations

-

The Ministry of Health should focus on low-utilization areas (Somali, Sidama, Gamo Gofa, and Gedo) with customized maternal health programs.

-

Regional Health Bureaus ought to enhance community education initiatives on maternal health, particularly targeting younger women and those with multiple children.

-

Both federal and local governments need to work on improving rural health infrastructure and access to help bridge the gap between urban and rural areas.

-

Health Extension Programs should give priority to women with lower education levels and those facing economic challenges.

Data availability

The data sets used and or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author up on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey

- FPMHSU:

-

Full Package Maternal Health Service Utilization

- EAs:

-

Enumeration areas

References

Berri, K. M., Adaba, Y. K., Tarefasa, T. G., Bededa, N. D. & Fekene, D. B. Maternal health service utilization from urban health extension professionals and associated factors among women who gave birth in the last one year in Ambo town, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia, 2018. BMC Public Health 20(1), 499 (2020).

Blaauw, D. & Penn-Kekana, L. Maternal health s on the Millennium Development Goals. S. Afr. Health Rev. 2010(1), 3–28 (2010).

Ahmed, S., Creanga, A. A., Gillespie, D. G. & Tsui, A. O. Economic status, education and empowerment: Implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS ONE 5(6), e11190 (2010).

Roser, M. & Ritchie, H. Maternal mortality (2024).

Maternal mortality. World Health Organization (2024).

Babalola, S. & Fatusi, A. Determinants of use of maternal health services in Nigeria–looking beyond individual and household factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 9, 43 (2009).

Birmeta, K., Dibaba, Y. & Woldeyohannes, D. Determinants of maternal health care utilization in Holeta town, central Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 13(1), 256 (2013).

Ononokpono, D. N., Odimegwu, C. O., Imasiku, E. & Adedini, S. Contextual determinants of maternal health care service utilization in Nigeria. Women Health 53(7), 647–668 (2013).

Rutaremwa, G., Wandera, S. O., Jhamba, T., Akiror, E. & Kiconco, A. Determinants of maternal health services utilization in Uganda. BMC Health Serv. Res. 15(1), 271 (2015).

Tarekegn, S. M., Lieberman, L. S. & Giedraitis, V. Determinants of maternal health service utilization in Ethiopia: Analysis of the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14(1), 161 (2014).

Dadi, T. L. et al. Continuum of maternity care among rural women in Ethiopia: Does place and frequency of antenatal care visit matter?. Reprod. Health 18(1), 220 (2021).

Kimport, K. No Real Choice: How Culture and Politics Matter for Reproductive Autonomy (Rutgers University Press, 2021).

Negash, W. D., Kefale, G. T., Belachew, T. B. & Asmamaw, D. B. Married women decision making autonomy on health care utilization in high fertility sub-Saharan African countries: A multilevel analysis of recent Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS ONE 18(7), e0288603 (2023).

Atnafu, A. et al. Determinants of the continuum of maternal healthcare services in Northwest Ethiopia: Findings from the primary health care project. J. Pregnancy 2020(1), 4318197 (2020).

Worldometre. Ethiopian Population-World meter. Accessed through https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/ethiopia-population/. Accessed 21 Jun 2023 (2023).

Yalew, M. et al. Spatial distribution and associated factors of dropout from health facility delivery after antenatal booking in Ethiopia: A multi-level analysis. BMC Womens Health 23(1), 79 (2023).

Public Health Institute (EPHI) CSAC. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey (2019 EMDHS) (EPHI and ICF, 2021).

Bulcha, G., Gutema, H., Amenu, D. & Birhanu, Z. Maternal health service utilization in the Jimma Zone, Ethiopia: Results from a baseline study for mobile phone messaging interventions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 24(1), 485 (2024).

Shanto, H. H. et al. Maternal healthcare services utilisation and its associated risk factors: A pooled study of 37 low- and middle-income countries. Int. J. Public Health 68, 1606288 (2023).

Temesgen, K. et al. Maternal health care services utilization amidstCOVID-19 pandemic in West Shoa zone, central Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 16(3), e0249214 (2021).

Melaku, M. S. et al. Geographical variation and predictors of zero utilization for a standard maternal continuum of care among women in Ethiopia: A spatial and geographically weighted regression analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22(1), 76 (2022).

Usman, M., Reddy, U. S., Siddiqui, L. A. & Banerjee, A. Exploration of spatial clustering in maternal health continuum of care across districts of India: A geospatial analysis of demographic and health survey data. PLoS ONE 17(12), e0279117 (2022).

Hiwale, A. J. & Das, K. C. Geospatial differences among natural regions in the utilization of maternal health care services in India. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 14, 100979 (2022).

Kurji, J. et al. Uncovering spatial variation in maternal healthcare service use at subnational level in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20(1), 703 (2020).

Banke-Thomas, O. E., Banke-Thomas, A. O. & Ameh, C. A. Factors influencing utilisation of maternal health services by adolescent mothers in Low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17(1), 65 (2017).

Emelumadu, O. F. et al. Socio-demographic determinants of maternal health-care service utilization among rural women in Anambra state, South East Nigeria. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 4(3), 374–382 (2014).

Elo, I. T. Utilization of maternal health-care services in Peru: The role of women’s education. Health Transit. Rev. 2, 49–69 (1992).

Govindasamy, P. & Ramesh, B. Maternal education and the utilization of maternal and child health services in India (1997).

CPC. The 2007 population and housing census of Ethiopia.

Debie, A., Khatri, R. B. & Assefa, Y. Contributions and challenges of healthcare financing towards universal health coverage in Ethiopia: A narrative evidence synthesis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22(1), 866 (2022).

Singh, P., Singh, K. K. & Singh, P. Maternal health care service utilization among young married women in India, 1992–2016: Trends and determinants. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21(1), 122 (2021).

Samuel, O., Zewotir, T. & North, D. Decomposing the urban–rural inequalities in the utilisation of maternal health care services: evidence from 27 selected countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod. Health 18(1), 216 (2021).

Sui, Y., Ahuru, R. R., Huang, K., Anser, M. K. & Osabohien, R. Household socioeconomic status and antenatal care utilization among women in the reproductive-age. Front. Public Health 9, 724337 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.F.A. and A.G.E. wrote the main manuscript text. A.G.Y., G.M.B., T.D.T., S.S.T., A.A.G., Z.A.A. and R.M.A. prepared figures 1–6 and Z.A.Y., A.T., A.S.E., G.Y., C.H.Y., A.M., B.A.M., M.A.A. and H.M. prepared tables 1–6. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained after permission to use the 2019 EDHS dataset was granted through an online request after explaining the study’s objectives. The dataset was only used for this study, in line with DHS policies.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, A.F., Ejigu, A.G., Yeshiwas, A.G. et al. Spatial distribution and determinants of full package maternal health service utilization in Ethiopia using 2019 Mini Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey. Sci Rep 15, 31053 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15720-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15720-3