Abstract

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is a significant global public health threat. HPV vaccination in males is crucial for reducing the risk of related cancers and partner infection. On the basis of the health belief model (HBM), this study delves into the factors influencing the willingness to receive HPV vaccination among male college students in Jinan. Using convenience sampling, a cross-sectional survey of 3,410 male students from six Jinan universities was conducted in December 2024. The structured questionnaires collected data on demographics, HPV knowledge, and health beliefs via SPSS 27.0 with univariate and binary logistic regression analyses. The results revealed that 88.5% of the participants were aware of HPV, with 77.7% willing to vaccinate. Univariate analysis revealed that lower grades, urban household registration, and adequate HPV knowledge were correlated with greater vaccination willingness, whereas average monthly consumption of ≥ 2,500 yuan was negatively correlated. Within the HBM, perceived susceptibility and self-efficacy positively predict vaccination willingness, whereas perceived severity and barriers have inhibitory effects. This study concludes that HPV vaccination intention among male university students in Jinan is influenced by sociodemographic factors, knowledge, and health beliefs. Higher willingness was linked to younger age and urban residence, while higher monthly expenditure correlated with lower intention. Adequate HPV knowledge significantly increased willingness, whereas lacking personal acquaintance with HPV-related disease was a barrier. Within the Health Belief Model, perceived benefits paradoxically associated with reduced intention, potentially due to “health illusion” among young adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is a global public health issue, and its long-term persistence can lead to cervical cancer and other malignancies1A US-based study reported that males develop over 9,000 HPV-related cancers annually, accounting for 63%, 91%, and 72% of penile, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers, respectively2. In China, male HPV infection is also a concern. Feixue Wei et al.3 reported a 10.5% HPV infection rate in males in South China, and Zhonghu He et al.4 reported a 17.5% rate in Anyang, Henan, from 2007 to 2009. Moreover, male HPV infection can indirectly increase female partners’ cervical cancer risk5.

The health belief model (HBM) is often used to explain vaccination willingness, especially when people do not readily accept disease prevention or screening for asymptomatic conditions6; it includes perceived susceptibility, severity, barriers, benefits, and self-efficacy7 and has shown strong explanatory power in studies of HPV and other viral vaccines8,9,10,11. Many studies have shown that HPV vaccines significantly reduce the burden of HPV-related cancers12,13,14. The WHO recommends incorporating HPV vaccines into national immunization programs as part of a comprehensive cervical cancer prevention strategy, along with enhanced health education, screening, and treatment services15.

Existing global research has extensively studied HPV-related cognition and vaccination willingness across different populations5,10,16,17.Yanru Zhang’s18 meta-analysis of 58 observational studies revealed HPV vaccination awareness and knowledge rates of 15.95% and 17.55%, respectively, with females having significantly higher rates than males. Several scholars19,20,21 also noted limited HPV-related cognition among Chinese individuals, especially males.

On January 18, 2025, Merck announced that its Gardasil®1 [Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)] had received multiple new approvals from China’s National Medical Products Administration for males aged 9–26, becoming the first and currently only HPV vaccine for males in China22. Previously, Chinese HPV research focused mainly on females, with few studies on male HPV cognition. Against this backdrop, our team chose male college students in Jinan, Shandong, as research subjects to investigate their HPV-related knowledge, vaccine cognition, and health beliefs. As a sexually active young group, in-depth research on the HPV-related situations of male college students can fill research gaps in specific male populations and provide a more comprehensive basis for public health strategies and vaccine promotion.

Materials and methods

Study population and sample size calculations

This cross-sectional study used a two-stage stratified cluster sampling method. In the first stage, stratified by junior colleges and undergraduate universities, the six universities in Jinan (Shandong Normal University, Shandong University of Art and Design, Shandong Labor Vocational College, Shandong Women’s University, and Shandong Shenghan College of Finance and Economics) were selected.In the second stage, male students enrolled in each of these six universities were selected, with the data collection conducted from December 1 to 31, 2024. The sample size was calculated via the cross-sectional survey formula23:

With Z1 − 2/α=1.96 for a 95% confidence interval, δ = 0.02, and P = 0.689 from Weiyi Wang’s study11, accounting for a 20% attrition rate, the calculated sample size was 2470, with a final sample size of 3410 participants included in the study to reduce individual-difference-induced bias and enhance result credibility and validity24,25.

Questionnaire design and distribution

On the basis of the health belief theory framework, the questionnaire was designed through a literature review and expert discussion in the field and was created on Wenjuanxing(https://www.wjx.cn/), which is a widely used online survey platform in China whose data security protocols have obtained ISO certification.

Prior meetings with school officials clarified specific details of the questionnaire.Subsequently, heads of each college disseminated the survey link through WeChat groups of individual classes. Participation was entirely voluntary without any coercion or monetary compensation, with strict guarantees for data confidentiality. Specifically, the sampling implementation covered 6 schools encompassing 59 majors, totaling 3410 participants, including 2125 freshmen, 804 sophomores, 345 juniors, and 136 seniors and above.

To reduce individual difference bias, the two-stage stratified cluster random sampling design was implemented: universities were stratified by type (junior colleges and undergraduate universities), with classes randomly selected within strata. For quality control, the questionnaire designers and principal investigators discussed implementation details with university administrators to address issues during and after survey completion, ensuring data quality. Quality control questions were included, such as gender-specific items (males required to select D) and first sexual intercourse timing, with 39 questionnaires excluded finaly.

The Jinan CDC team managed the data export and review, while the participants completed the survey via smartphones or computers. The questionnaire covered:

General sociodemographic characteristics

Age, household registration, ethnicity, monthly consumption, and parents’ education level were included.

HPV-related knowledge

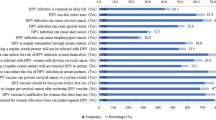

An 11-item HPV knowledge questionnaire was developed through a literature review and expert discussion (Table 1). Each question had “Yes”, “No”, or “Unclear” options, with 1 point for correct answers. Students who answered more correctly than 7 questions were deemed HPV-knowledge-qualified. The Cronbach’s α was 0.847, indicating good internal consistency and validity.

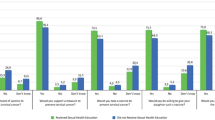

HPV health beliefs

An HPV-specific health belief questionnaire was developed, covering 16 items across five dimensions: perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy. A 5-point Likert scale was used, with responses ranging from “Strongly disagree” (1 point) to “Strongly agree” (5 points). Higher dimension scores indicate greater participant agreement. (Table 2). The overall Cronbach’s α of the health belief scale was 0.896, and the range of each dimension ranged from 0.667 to 0.889,indicating good internal consistency and validity.

Data analysis and cleaning

SPSS 27.0 was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were generated, with counts expressed as component ratios. Univariate analysis and binary logistic regression were used to identify influencing factors.

Research results

Of the 3,449 questionnaires collected, 3,410 were valid (98.87%). Most respondents were aged 16–21 years (89.1%), were of Han ethnicity (97.7%), and were of rural origin (70.6%). A total of 54.0% had a monthly consumption of ≤ 1,500 yuan. Their parents’ education was mainly junior high school or below (42.0%) or high school (36.3%). A total of 73.8% were single, and 15.2% had sexual experience. A total of 88.5% had heard of HPV, and 77.7% (2,650) were willing to be vaccinated. (Table 3).

Univariate analysis revealed significant associations between willingness to receive HPV vaccination and various social, demographic and cognitive factors. Notably, significant differences in vaccination willingness were found across grades, with freshmen having the highest willingness (78.59%) and seniors having the lowest willingness (48.00%) (χ² = 16.709, P = 0.002). Significant variations were also observed in religious belief (χ² = 4.821, P = 0.028), urban household registration (χ² = 6.445, P = 0.011), younger age groups (≤ 20 years old, χ² = 13.153, P = 0.001), and higher monthly consumption levels (χ² = 18.142, P < 0.001). Moreover, participants who had heard of HPV (χ² = 111.755, P < 0.001), had received sex education (χ² = 110.097, P < 0.001), or had greater HPV-related knowledge (χ² = 259.209, P < 0.001) presented greater vaccination willingness (Table 4).

Univariate analysis based on the health belief model revealed that students with different levels of vaccination willingness had significantly different scores in each dimension (P < 0.05). Those with higher perceived susceptibility, benefits, and self-efficacy were more willing to be vaccinated, whereas higher perceived severity and barriers were associated with lower willingness (Table 5).

With vaccination willingness as the dependent variable and social-demographic characteristics (grade, household registration, religious belief, age, monthly consumption, and sexual orientation), HPV-related information (awareness of HPV, sex education, acquaintance with condyloma acuminata patients, and HPV-related knowledge), and total health belief scores as covariates, binary logistic regression was performed (Table 6).

The results revealed that a monthly consumption of ≥ 2,500 yuan (OR = 0.524, 95% CI: 0.362–0.759) was negatively correlated with vaccination willingness. Those who had heard of HPV (OR = 1.512, 95% CI: 1.169–1.954), had qualified HPV knowledge (OR = 2.203, 95% CI: 1.807–2.685), or sex education (OR = 1.639, 95% CI: 1.328–2.023) as well as a higher Health Belief Score (OR = 1.459, 95% CI: 1.349–1.577) were more willing to be vaccinated.Regarding Condyloma Acuminatum occurrence in family/friends, reporting “None” was a risk factor (OR = 1.992, 95% CI: 1.12–3.541) while “Not clear” was protective (OR = 0.688, 95% CI: 0.545–0.869).Perceived benefits(OR = 0.658, 95% CI: 0.596–0.727) hinder vaccination.Because perceived susceptibility (OR = 0.714, 95% CI: 0.641–0.794),severity (OR = 0.639, 95% CI: 0.584–0.698) and barriers (OR = 0.641, 95% CI: 0.586–0.701) were inversely scored, these two factors are considered protective factors for vaccination.School category was not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Table 7).

Discussion

This study combined sociodemographic characteristics and HPV awareness and clarified the factors influencing HPV vaccination intentions on the basis of the health belief model. The results reveal a complex interplay between structure, education, and health belief dimensions. These findings can provide scientific guidance for the implementation of targeted interventions in the future.

Beyond economic determinants: sociodemographic variations

Our study revealed that 88.5% of the male college students in Jinan had heard of HPV, and 62.3% had adequate HPV knowledge, surpassing international averages26,27,28,29,30. This may be due to Jinan’s status as a national pilot city for cervical cancer prevention and control, with active government-led vaccination initiatives since 2021, initially offering free HPV vaccination to eligible girls and later expanding to boys31,32. Collaborative efforts across departments, including health education and publicity, have also contributed. For example, education departments conduct school-based registration, whereas health health administrative departments and the CDC handle vaccinations33. Younger students (≤ 20 years old) and those with urban household registration exhibit greater vaccination willingness, which aligns with the findings of Erika L. Thompson’s study, which revealed that American male college students aged 18–21 years were more likely to be vaccinated than those aged 22–26 years were34 and with global research trends35,36,37.

Notably, a higher monthly expenditure (≥ 2,500 yuan) was associated with lower vaccination willingness, contradicting the traditional assumption that economic capability generally promotes health engagement38,39. The relationship may be complex and depend on how these funds are allocated.In the Chinese context, students with higher expenditures may prioritize lifestyle and personalized consumption, such as fashion, entertainment, and dining40,41, potentially viewing discretionary health expenditures like HPV vaccination which is not covered by national medical insurance and carries a significant cost for the full course with greater caution42.Furthermore, research indicates that male students’ dietary habits and health perceptions may be comparatively less developed43,44.The above students might rely more on lifestyle measures like balanced diets, regular exercise, or premium health supplements, perceiving these as sufficient for maintaining health and reducing the perceived necessity of preventive vaccination. The results of our study differs from studies by Peiwan Fang45, Xinyue Lu46, which suggested higher expenditure students were more willing to vaccinate. This discrepancy could arise if a subset of high-expenditure students in those studies allocated funds towards active self-improvement, potentially reflecting better health behaviors and higher vaccination willingness. The specific expenditure patterns within the high-spending group in the present study warrant further investigation in future research.

Interaction between knowledge and social attributes

International scholars have emphasized that disease-related knowledge can better serve beliefs, which is consistent with our findings that HPV knowledge and sex education promote vaccination willingness47,48,49. Remarkably, students with adequate HPV knowledge were more than twice as willing to be vaccinated as those without (OR = 2.203, 95% CI: 1.807–2.685), underscoring the critical role of health education. When they fully understand HPV transmission, harm, and vaccine preventive effects, they are more likely to view vaccination as an effective self-protection measure9.

Moreover, multivariate logistic regression revealed that lacking personal acquaintance with condyloma acuminata patients or being unaware of such cases was a barrier to vaccination willingness, similar to Zhenwei Dai’s16 and Alex’s findings50. People often assess their health risks by referencing others’ experiences. Without real-life cases, male college students may perceive HPV infection as distant, reducing their degree of vaccination urgency.

Health belief model: the paradox of perceived benefits

Consistent with HBM expectations, vaccine-willing individuals presented significantly greater perceived susceptibility, severity, which aligns with the findings of GEREND M A10 and SONG S Y’s9 research. Perceived susceptibility enhances risk assessment, increasing vaccination willingness51, Research by scholars such as Katekaew Seangpraw52 also suggests that people who perceive diseases as harmful are more likely to make decisions to protect their health, and therefore they may be more likely to get vaccinated.

However, our study revealed a paradox that perceptual impairment promotes vaccination behavior, while perceived benefit hinders vaccination behavior.Research indicates that when vaccination is combined with strong cues to action, barriers may be transformed into motivation. As noted by Chenwen Claire Zhong53, while perceived benefits can increase vaccination intention by 3.92 times, the enhancing effect of cues to action (such as healthcare professionals’ recommendations) proves even more significant.Similarly, researcher Peng Yalan54 and ADIYOSO W55emphasize that strengthening vaccine education, clarifying disease risks, highlighting vaccine benefits, and utilizing advertising campaigns constitute effective strategies for improving vaccination rates. Prior to survey distribution, we conducted relevant knowledge lectures in each participating school, which may represent an influential factor. However, the specific contribution level of these lectures to vaccination intention merits further investigation.

Additionally, relevant studies indicate that self-rated healthy individuals exhibit a 46.2% reduction in vaccination intention53, highlighting the “health illusion” effect. In this study, the male university student cohort consisted primarily of first-year undergraduates—typically characterized by youthful vigor and physical robustness—who may harbor optimism bias leading to underestimation of infection risks56. This consequently manifests as higher perceived benefits coexisting with lower vaccination intention.

Conclusions

This study identified factors influencing HPV vaccination intention among male university students in Jinan, China, using the Health Belief Model and sociodemographic analysis. Younger age (≤ 20 years) and urban household registration correlated with higher vaccination willingness. Students with higher monthly expenditure (≥ 2,500 yuan) exhibited lower vaccination intention, suggesting potential prioritization of lifestyle consumption or alternative health measures over discretionary vaccination costs. Adequate HPV knowledge more than doubled vaccination willingness (OR = 2.203, 95% CI: 1.807–2.685). Lack of personal acquaintance with condyloma acuminata cases acted as a barrier to vaccination. Perceived susceptibility and severity aligned with HBM expectations in promoting intention. However, perceived benefits were associated with lower vaccination intention, potentially explained by the “health illusion” effect among young, healthy students. The findings demonstrate a complex interplay of sociodemographic, knowledge, and health belief factors.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design excludes causal inferences, although it may provide a basis for factors related to vaccination willingness. Secondly, although the strict two-stage hierarchical cluster sampling improves the internal validity, the data in this study are from 6 efficient schools in Jinan, which may limit the representativeness and universality of the data. Third, self-reported data may introduce social desirability bias; Finally, quantitative measures could not fully capture complex socio-cultural factors, which qualitative approaches should explore.

Policy recommendations

Targeted Health Promotion: Intensify publicity for younger and urban-registered students to reinforce their vaccination willingness. For older and rural registered students, HPV education can be enhanced through diverse channels.

Digital Interventions: Digital measures should be integrated into traditional health promotion, vaccine-related information should be managed strictly, and misinformation should be curbed to alleviate safety concerns.

Case-Sharing and Risk Communication: Organize cases—sharing sessions with HPV-infected individuals or professionals to vividly illustrate HPV risk. Health departments and schools should conduct regular risk communication to update students on HPV trends and prevention.

Balanced Fear Appeals: When disseminating HPV information, use fear appeals judiciously to motivate behavioral change without causing excessive fear. This study presents information in a scientific, objective, and comprehensible manner to minimize cognitive dissonance and prevent vaccine avoidance due to psychological defenses.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they involve in-depth investigations but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

GRAVITT P E, WINER, R. L. Natural history of HPV infection across the lifespan: role of viral latency [J]. Viruses, 9(10). (2017).

HAN, J. J. et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus infection and human papillomavirus vaccination rates among US adult men: National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2013–2014 [J]. JAMA Oncol. 3 (6), 810–816 (2017).

WEI, F. et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence and associated factors in women and men in South china: a population-based study [J]. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 5 (11), e119 (2016).

HE, Z. et al. Human papillomavirus genital infections among men, china, 2007–2009 [J]. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19 (6), 992–995 (2013).

BOSCH F X, CASTELLSAGUé, X. et al. Male sexual behavior and human papillomavirus DNA: key risk factors for cervical cancer in Spain [J]. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 88 (15), 1060–1067 (1996).

EASTON-CARR, A. L. Y. A. F. E. I. A. R. The Health Belief Model of Behavior Change [M]. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL); StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025 (StatPearls Publishing LLC, 2025).

ALICIA NORTJE P D. What is the health belief model?? An updated look [EB/OL] 12 Apr 2024 https://positivepsychology.com/health-belief-model/

YI, Y. et al. Perceptions and acceptability of HPV vaccination among parents of female adolescents 9–14 in china: A cross-sectional survey based on the theory of planned behavior [J]. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 19 (2), 2225994 (2023).

SONG S Y, GUO, Y. et al. Analysis of factors influencing HPV vaccination intention among Chinese college students: structural equation modeling based on health belief theory [J]. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1510193 (2024).

GEREND M A, SHEPHERD, J. E. Predicting human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in young adult women: comparing the health belief model and theory of planned behavior [J]. Ann. Behav. Med. 44 (2), 171–180 (2012).

WANG, W. The role of personal health beliefs and altruistic beliefs in young Chinese adult men’s acceptance of the human papillomavirus vaccine [J]. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 20341 (2024).

HARPER D M & DEMARS L R. HPV vaccines - A review of the first decade [J]. Gynecol. Oncol. 146 (1), 196–204 (2017).

JOURA E A et al. A 9-Valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women [J]. N. Engl. J. Med. 372 (8), 711–723 (2015).

FORMAN, D. et al. Global burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases [J]. Vaccine 30, F12–F23 (2012).

Human papillomavirus vaccines. WHO position paper, May 2017 [J]. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 92 (19), 241–268 (2017).

Dai, Z. et al. Willingness to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and influencing factors among male and female university students in China. J. Med. Virol. 94(6), 2776–2786 (2022).

GUILAN, X., XIAOJING, Q. & LU, Q. Analysis on the cognition of cervical cancer and HPV vaccine among female college students in Beijing [J]. Chin. J. Reproductive Health. 32 (01), 32–35 (2021).

ZHANG, Y. et al. Awareness and knowledge about human papillomavirus vaccination and its acceptance in china: a meta-analysis of 58 observational studies [J]. BMC Public. Health. 16, 216 (2016).

LIU C, R. et al. Effect of an educational intervention on HPV knowledge and attitudes towards HPV and its vaccines among junior middle school students in chengdu, China [J]. BMC Public. Health. 19 (1), 488 (2019).

BALOCH, Z. et al. Knowledge and awareness of cervical cancer, human papillomavirus (HPV), and HPV vaccine among HPV-Infected Chinese women [J]. Med. Sci. Monit. 23, 4269–4277 (2017).

WANG, S. et al. Do male university students know enough about human papillomavirus (HPV) to make informed decisions about vaccination?? [J]. Med. Sci. Monit. 26, e924840 (2020).

MERCK’S. Merck’s Gardasil® becomes the first and currently the only HPV vaccine approved in China that can be applied to men. [EB/OL] 2025.1.18 https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/g4bMqwMAjZU9Alur5wJB0A

CHARAN, J. & BISWAS, T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? [J]. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 35 (2), 121–126 (2013).

MY W. Analysis ofHPV vaccination intention and influencing factors among ruralwomen in Guangxi minority areas [D], (2024).

ML C. Survey on awareness ofhuman papillomavirus vaccineand analysis of influencing factors of vaccinationintention among 18–45 (2025). years old women [D].

GUILAN, X. et al. Analysis on the cognition of cervical cancer and HPV vaccine among female college students in Beijing [J]. Chin. J. Reproductive Health. 32 (01), 32–35 (2021).

LI, M. et al. Awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine among college students in China [J]. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1451320 (2024).

PAN X F, ZHAO Z M, SUN, J. et al. Acceptability and correlates of primary and secondary prevention of cervical cancer among medical students in Southwest china: implications for cancer education [J]. PLoS One. 9 (10), e110353 (2014).

SHIMBE, M. et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination awareness and uptake among healthcare students in Japan [J]. J. Infect. Chemother. 31 (2), 102554 (2025).

PATEL, H. et al. Knowledge of human papillomavirus and the human papillomavirus vaccine in European adolescents: a systematic review [J]. Sex. Transm Infect. 92 (6), 474–479 (2016).

TENCENT. Latest survey: Only 5% have not heard of HPV vaccine, but less than 40% have been vaccinated! The most common ice-breaking motivation is… EB/OL] 2023.7.1 https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20230701A0284000.

HEALTH. Accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer · in action | jinan, shandong: orderly promote vaccination for girls of appropriate age. [EB/OL] 12.9 (2024). https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_29597437

NEWS C. Stay away from HPV infection and scientifically safeguard health! Jinan takes multiple measures to help teenagers grow up healthily. [EB/OL] 12.30 (2024). https://city.sina.cn/news/2024-12-30/detail-inecfrav1258903.d.html

THOMPSON E L, VAMOS C A, VáZQUEZ-OTERO, C. et al. Trends and predictors of HPV vaccination among U.S. College women and men [J]. Prev. Med. 86, 92–98 (2016).

HAO N T M, KHANH H V N, LIAMPUTTONG, P. et al. HPV Vaccine Uptake by Young Adults in Hanoi, Vietnam: A Qualitative Investigation [J]23100619 (X, 2025).

LAJOIE A S et al. Influencers and preference predictors of HPV vaccine uptake among US male and female young adult college students [J]. Papillomavirus Res. 5, 114–121 (2018).

WANG, W. The impact of vaccine access difficulties on HPV vaccine intention and uptake among female university students in China [J]. Int. J. Equity Health. 24 (1), 4 (2025).

MAHUMUD, R. A. et al. Cost-effectiveness evaluations of the 9-Valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: evidence from a systematic review [J]. PLoS One. 15 (6), e0233499 (2020).

SCHüLEIN, S. et al. Factors influencing uptake of HPV vaccination among girls in Germany [J]. BMC Public. Health. 16, 995 (2016).

XIANGMING, K., HUI, W. & LIN, Z. Survey research on health consumption expenditure of contemporary college students [J]. China Electr. Power Educ., (07): 179–182. (2010).

ZIHAO, W. et al. The impact of consumption upgrade on the fashion consumption of youth in China [J]. Market Modernization, (18): 55–56. (2018).

LI, Y. & QIN, C. The effectiveness of pay-it-forward in addressing HPV vaccine delay and increasing uptake among 15-18-year-old adolescent girls compared to user-paid vaccination: a study protocol for a two-arm randomized controlled trial in China [J]. BMC Public. Health. 23 (1), 48 (2023).

JINFANG, D. & SHENGYONG, W. Logistic regression analysis on risk factors of unhealthybehavior among college students [J]. Chin. J. Disease Control Prev. 14 (10), 953–955 (2010).

GUOPING, D. et al. Health-risk behaviors amongcollege students and associatedfactors [J]. Chin. J. School Health. 36 (05), 711–714 (2015).

FANG, P. et al. Factors influencing knowledge and acceptance of nonavalent human papillomavirus vaccine among university population in Southern china: A Cross-Sectional study [J]. Cancer Control. 31, 10732748241293989 (2024).

LU, X. et al. Willingness to pay for HPV vaccine among female health care workers in a Chinese nationwide survey [J]. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22 (1), 1324 (2022).

QIAO Y, ANALYSIS OF THE CURRENT SITUATION AND PROBLEMS OF KAP FOR CHILDREN’S & BRONCHIAL ASTHMA PREVENTION AND TREATMENT SERVICES BY PRIMARY CARE GENERAL PRACTITIONERS IN CHONGQING. [D]; ChongQing Medical University, (2024).

ANDRADE, C. & MENON, V. Designing and conducting knowledge, attitude, and practice surveys in psychiatry: practical guidance [J]. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 42 (5), 478–481 (2020).

PAPASTERI, C. & LETZNER R D, P. A. S. C. A. L. S. Pandemic KAP framework for behavioral responses: initial development from lockdown data [J]. Curr. Psychol. 43 (26), 22767–22779 (2024).

KOSKAN, A. & STECHER, C. College males’ behaviors, intentions, and influencing factors related to vaccinating against HPV [J]. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 17 (4), 1044–1051 (2021).

PETRIE K J, W. E. I. N. M. A. N. J. Why illness perceptions matter [J]. Clin. Med. (Lond). 6 (6), 536–539 (2006).

SEANGPRAW, K. et al. Using the health belief model to predict vaccination intention among COVID-19 unvaccinated people in Thai communities [J]. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 890503 (2022).

ZHONG, C. C. et al. Factors associated with willingness among adults to receive Pneumococcal vaccine in Hong kong: a cross-sectional study using HBM constructs [J]. Vaccine 62, 127544 (2025).

PENG, Y. et al. Exploring perceptions and barriers: A health belief Model-Based analysis of seasonal influenza vaccination among High-Risk healthcare workers in China [J]. Vaccines (Basel), 12(7). (2024).

ADIYOSO, W. The use of health belief model (HBM) to explain factors underlying people to take the COVID-19 vaccine in Indonesia [J]. Vaccine X. 14, 100297 (2023).

RATNAPRADIPA K L, NORRENBERNS, R. et al. Freshman flu vaccination behavior and intention during a nonpandemic season [J]. Health Promot Pract. 18 (5), 662–671 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the support provided by the Changqing District CDC of Jinan and the staff of the universities involved in the study, particularly for their assistance with on-site data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by the PKU-MSD Joint Laboratory on Infectious Disease Prevention and Control and the Haiyou Health High-Caliber Talent Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Caiyun Chang and Qingbin Lu conceived and designed the study and developed the initial research plan.Yanrui Xu performed the data analysis and drafted the initial manuscript.Li Yang, Xing Chen, and Xiaonan Yang contributed to the revision of the manuscript.Weibing Wang and Caiying Cheng coordinated with university officials for questionnaire distribution.All the authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki principles, obtained informed consent from all participants, ensured strict data confidentiality for scientific research use only, and was approved by the Jinan Center for Disease Control and Prevention Ethics Committee (approval No: 2025–001).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Y., Wang, W., Cheng, C. et al. Factors influencing HPV vaccination willingness among male college students in Jinan according to the health belief model. Sci Rep 15, 30369 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16299-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16299-5