Abstract

Declining water quality poses serious environmental and public health risks, with chlorophyll-a serving as a key biological indicator of harmful algal blooms. This study evaluates the use of a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network to forecast chlorophyll-a concentrations in the Chesapeake Bay, a critical estuarine ecosystem supporting over 17 million people. Weekly satellite-derived chlorophyll-a measurements from 1997 to 2020 were collected for three geographic regions of the bay. The LSTM model was benchmarked against traditional statistical models, including ARIMA and TBATS, and trained to capture complex seasonal patterns in the time series data. Across all three regions, the LSTM consistently outperformed the other models, achieving lower root mean squared error (RMSE) values of 0.121, 0.155, and 0.199 mg/m3. These results demonstrate the LSTM model’s superior ability to learn spatiotemporal dynamics and accurately predict future chlorophyll-a levels. This work highlights the potential of deep learning approaches to improve water quality forecasting, inform timely policy decisions, and support sustainable management of aquatic ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As human populations grow and industrial activities expand, water quality degradation has become a pressing global issue1. Every year, unsafe or inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene are estimated to contribute to approximately 1.4 million deaths worldwide2, illustrating the severe impacts of water pollution on ecosystems and public health. Monitoring the quality of water in rivers, lakes, and estuaries is therefore essential for assessing human impacts on aquatic environments and the effectiveness of remediation efforts. Chemical, physical, and biological water quality indicators provide critical information for evaluating ecosystem health and guiding management policies, as well as establishing reasonable goals and standards for future water quality endeavors.

Chlorophyll-a (chl-a), the predominant photosynthetic pigment in algae, cyanobacteria, and plants, is one such key biological indicator whose concentration in water serves as a proxy for algal biomass and distribution. In practical terms, “algae” encompasses a broad range of chlorophyll-containing aquatic organisms, including phytoplankton, macroalgae (seaweed), and pond scum. Chlorophyll-a levels are widely used to monitor algal growth and trophic status, making it an important metric for evaluating water quality. Elevated algal production is often associated with nutrient enrichment and can trigger eutrophication. As algal biomass increases, water transparency declines and decomposition of excess algae depletes dissolved oxygen, creating hypoxic conditions that are harmful to fish and other wildlife. In extreme cases, algal blooms can produce toxins and render water unsafe for human and animal use. Monitoring chlorophyll-a thus helps in the early detection and prevention of harmful algal bloom events that threaten ecosystem and public health3,4,5,6.

Machine learning techniques have emerged as powerful tools for modeling complex environmental patterns, including chlorophyll dynamics. For example, Blix and Eltoft (2018) applied a machine learning algorithm to retrieve oceanic chlorophyll-a concentrations on a global scale with high accuracy7. However, such approaches have not been fully explored for more localized and vital regional water bodies that directly affect large human populations. The Chesapeake Bay—the largest estuary in the United States—is a prime example, supporting a watershed population of over 17 million people and providing crucial ecological and economic services. Long-term observations indicate that Chesapeake Bay water quality has been deteriorating in recent decades, with persistently high chlorophyll-a levels linked to eutrophication and low-oxygen “dead zones”8,9. There is a clear need for reliable predictive models that can forecast chlorophyll-a trends in such systems to inform timely management actions.

The aim of this study is to (1) implement and evaluate LSTM-based models across 3 subregions of the Chesapeake Bay from data collected from in situ measurements and satellite-based sensors; (2) assess model performance using in situ chlorophyll-a measurements over a 1-week prediction horizon to support proactive water quality management; (3) determine whether LSTMs can outperform traditional ARIMA (Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average) and TBATS (Trigonometric seasonality, Box-Cox transformation, ARIMA errors, Trend, Seasonal components) models in capturing the complex interannual dynamics of chlorophyll-a; and (4) benchmark results against existing literature. To our knowledge, this is the first application of LSTM networks for chlorophyll-a prediction in the Chesapeake Bay, making each component—from dataset integration to model design and temporal scope—novel.

Literature review

Machine learning for water quality monitoring

Early water-quality forecasting relied on mechanistic models or univariate time-series methods (e.g. ARIMA)10,11,12. However, these traditional methods struggle to capture long-term patterns and nonlinear dynamics inherent to water quality prediction, with many factors such as nutrient loads and sediment concentration having a joint effect on algal growth rates13,14,15. By contrast, data-driven methods such as support vector regression (SVR), decision trees and neural networks (NNs) can learn complex patterns without detailed process assumptions, making them a popular choice for water quality forecasting. For example, random forest models have been applied to predict nutrient concentrations and turbidity in large river systems with high accuracy16. Deng et al. (2021) applied SVR and ANN models to predict the quality of marine water in the Tolo Harbour in Hong Kong17.

However, shallow ML models (RF, SVR, NN) are still constrained by the inability to capture patterns over long periods of time because they generally treat lagged observations as independent input features and lack mechanisms to retain states across extended time spans. Deep learning methods—such LSTMs—can overcome this limitation, effectively capturing temporal dependencies beyond linear memory limits. On the coast of subtropical Sabah, Malaysia, Yussof et al. (2021) used MODIS-derived Chl-a as a proxy for harmful algal blooms; their LSTM outperformed a CNN model trained on the same data18. Cen et al. (2022) trained an LSTM on 10 years of satellite-derived chlorophyll-a in the East China Sea to forecast five days ahead, successfully reproducing seasonal patterns with RMSEs as low as 0.0223 mg/m^319. Eze et al. (2021) combined ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD) with LSTM to predict hourly and daily Chl-a at a salmon farm, achieving high precision with 3 months’ worth of data20,21. In general, deep learning methods tend to outperform both traditional models (ARIMA, TBATS) and shallow ML (RF, SVR) for forecasting nonlinear variables.

A limitation of deep learning methods is the lack of data availability, which can help improve accuracy. Most existing time-series studies for water quality monitoring use data spanning several months to 15 years18,19,20,22,23,24. We apply LSTMs to a larger, more studied body of water—the Chesapeake Bay—which has over 20 years of available and accurate Chl-a data. This allows us to create a dataset of unprecedented size with potential for higher accuracy, motivating our use of training better-informed LSTMs as the primary predictor, and ARIMA/TBATS for benchmarking.

Forecasting in coastal and estuarine environments

Coastal and estuarine environments are of particular importance due to their complex hydrodynamics and proximity to human populations. Some previous studies have explored the applications of deep learning to these regions. For example, Lin et al. (2023) constructed a flexible pipeline (SVR, RF, wavelet-BPNN and wavelet‐LSTM) to predict chlorophyll-a in two coastal systems (the Neuse River Estuary and a Pacific Pier site), finding that wavelet‐filtered LSTM and BPNN yielded the most robust bloom forecasts24.

In addition to chlorophyll, other key water-quality variables have been forecast using ML. Dissolved oxygen (DO) is a common target: Gachloo et al. (2024) developed ML and LSTM models for short-term DO forecasting in a microtidal estuary to enhance ecosystem restoration by providing timely warnings of hypoxia events25. Zhu et al. (2022) applied an ensemble of ML regressors to Sentinel-2 satellite imagery in Shenzhen Bay (a coastal estuary) to estimate Chl-a, turbidity and dissolved oxygen simultaneously, achieving errors of only ~ 1–2% by optimizing spectral band inputs with Shapley analysis26. While forecasting Chl-a alone yields interpretable, actionable results (e.g. bloom alerts), including dissolved oxygen, nutrients or other covariates can refine accuracy. These coastal studies underscore that ML approaches can handle multivariate and spatial datasets (satellite or sensor-based) to produce useful near-term water-quality forecasts.

However, there is a large gap in research on forecasting water quality parameters (including chl-a) with deep learning in estuarine regions specifically. Notably, there has been no application of an LSTM to predict Chl-a in the Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in the United States, and one of the largest in the world. In the present study, we therefore focus solely on Chl-a prediction to provide a clear, understandable proxy for ecosystem response, while recognizing that future extensions could incorporate additional parameters and use this single-variable model as a baseline comparison for multivariate models.

Prediction time horizons and management feasibility

A critical yet underexplored aspect in the application of machine learning to chlorophyll-a and algal bloom prediction is the choice of prediction horizon and its practical implications for water quality management. Most existing studies on machine learning-based chlorophyll-a prediction have concentrated on extremely short prediction windows, typically ranging from 6 h to 1–3 days20,22,23,27,28. While these ultra-short-term predictions can achieve impressive accuracy metrics—often exceeding 90% in terms of correlation coefficients or achieving very low RMSE values—they provide limited practical utility for proactive management responses.

From an ecological perspective, harmful algal blooms can develop incredibly fast, and have been recorded to form over periods as small as several hours to a few days, including in the Chesapeake Bay itself29,30. Recent studies emphasize that forecasting windows on the scale of multiple days to weeks are most actionable for managers, who require warnings early enough to deploy response measures (e.g. public advisories, treatment protocols, equipment adjustments) yet short enough to minimize prediction uncertainty31,32. A 2017 case study in Lake Utah, for instance, showed that in the absence of forecasting tools, public warning decisions lagged behind bloom onset by up to 7 days — leading to potentially avoidable economic losses of up to $1 M + depending on factors like bloom size and exposure33. The 7-day delay encompassed the average time it takes for a bloom to be spotted, reported, on-site testing to occur, analyze the results, make a decision to post warnings, and then finally post the warnings, suggesting the criticality of predicting blooms at last a week in advance.

Timelag analysis of algal bloom drivers further supports this scale. A 2021 study by Liu et al. found that phytoplankton response to environmental drivers often exhibits a lag of 7–14 days, depending on species and hydrological transport processes; shorter timelags (2–4 days) occur in certain lakes, but estuarine/coastal blooms more commonly manifest after 1 week of antecedent forces such as nutrient pulses, temperature shifts, or stratification events34. This suggests that forecast windows shorter than one week may miss the full causal signal, while longer windows may introduce noise or reduced leadtime utility.

Thus, our choice of a one-week prediction horizon represents a careful and effective compromise between predictive accuracy and management utility, while preserving alignment with ecological lag responses. This uniquely positions our model to be a robust tool for effective water quality management, providing sufficient lead time for most immediate response actions with reliable predictivity.

Methods

Data collection and processing

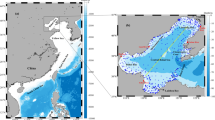

The Chesapeake Bay was divided into three regions (lower Bay, middle Bay, and upper Bay) for the purposes of this study, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The upper Bay constitutes the region above 38.6° N longitude, the middle Bay between 37.6° and 38.6° N longitude, and the lower Bay south of 37.6° N longitude35. Weekly chlorophyll-a concentration data (in mg·m^−3) for each region from 1997 to 2020 were obtained using NASA’s SeaWiFS Bio-optical Archive and Storage System (SeaBASS) Regional Time Series tool. The chlorophyll-a measurements consisted of near-surface concentrations derived from four satellite sensors (SeaWiFS, MODIS-Aqua, MODIS-Terra, and VIIRS-SNPP) as well as in situ observations compiled by SeaBASS. All individual observations were aggregated into calendar weeks (Monday–Sunday) and averaged to produce a continuous weekly time series for each region, yielding 1,209 weekly data points per region. The three regional time series each contained a small fraction of missing values (less than 1% of weeks); these gaps were infilled by linear interpolation to maintain a complete record. The data processing and time series assembly were performed using Python (pandas library).

Statistical time series models (ARIMA/TBATS)

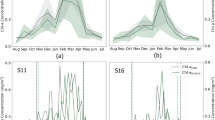

We benchmarked the performance of the deep learning model against two conventional time-series forecasting models: an ARIMA model and a TBATS model. Prior to fitting these models, we analyzed the chlorophyll-a time series for seasonal patterns. Each regional series was decomposed using Seasonal-Trend decomposition based on Loess (STL) to identify significant periodic components. The decomposition (illustrated in Fig. 2) revealed multiple seasonal frequencies in the data, with particularly strong cyclic behavior at the weekly and quarterly scales. These two periods (approximately 7 days and 3 months, corresponding to intra-seasonal and seasonal bloom cycles) were therefore selected as the seasonal components for the multiple-seasonality time series (MSTS) structure.

For the TBATS model, we utilized an implementation from the forecast package in R. Each regional chlorophyll-a time series was first converted into a multiple seasonal time series (MSTS) format incorporating the identified weekly and quarterly periodicities. We partitioned each dataset into a training set (85% of the data, corresponding to the years 1997–2016) and a testing set (the remaining 15%, approximately 2017–2020). The TBATS model was then automatically fitted to the training portion of each MSTS. The model’s internal parameters (including whether to apply a Box-Cox transformation and damping on trend) were estimated from the data. The fitted TBATS model produces forecasts by jointly modeling the multiple seasonal cycles along with any long-term trend and autocorrelation structure in the residuals.

For the ARIMA model, we similarly used 85% of each regional dataset for training and reserved the final 15% for testing the forecasts. We employed the auto.arima function from the R forecast package to automatically select optimal ARIMA model parameters for each training series. This automated selection considers differencing orders and ARIMA(p, d,q) terms that best fit the data (minimizing the corrected Akaike Information Criterion, or AICc). To improve the ARIMA model’s ability to handle the complex seasonal patterns in the chlorophyll-a series, we incorporated Fourier series terms as exogenous regressors representing the prominent seasonal cycles. Specifically, Fourier terms for the weekly and quarterly frequencies were included in the ARIMA model to capture those periodic components. The number of Fourier terms for each frequency was chosen by the algorithm based on AICc optimization. This approach allows the ARIMA model to approximate multiple seasonality by modeling seasonal effects in the residuals with sinusoidal terms. The final ARIMA models were checked for adequacy via residual diagnostics; in each case, diagnostic tests (e.g., Ljung–Box test) confirmed that no significant autocorrelation remained in the residuals, indicating that the models had accounted for the major serial dependencies in the training data.

All statistical modeling was conducted in the R environment using standard forecasting libraries. The forecast accuracy of the ARIMA and TBATS models was evaluated on the held-out test data (2017–2020) by comparing the predicted weekly chlorophyll-a values against the true observed values and computing error metrics (ME, RMSE, MAE, MAPE) as reported in the Results.

LSTM neural network

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are a class of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) designed to capture long-range temporal dependencies in sequential data by incorporating memory cells and gating mechanisms36. At each time step t, the LSTM maintains two key internal states: the cell state ct and the hidden state ht, which are updated through gated operations that control the flow of information. The forget gate ft determines which information from the previous cell state ct−1 is retained via the following equation:

where xt is the input at time t, ht−1 is the hidden state from the previous time step, Wf and Uf are weight matrices, bf is the bias term, and σ(⋅) denotes the sigmoid activation function37.

The input gate it controls how much new information flows into the cell, while the candidate cell state \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{c}}_{t}\) represents the new content potentially added to the memory:

The cell state is then updated by combining the retained previous state with the new candidate state:

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication. Finally, the output gate ot determines the next hidden state ht:

This structure allows LSTMs to selectively remember or forget information, making them effective for modeling complex, nonlinear temporal patterns in environmental time series38,39. Figure 3 represents the structure of a single LSTM unit, multiple of which make up an LSTM layer.

In our study, we also used bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) units, which extend the standard LSTM by incorporating two parallel LSTM layers that process the input sequence in both forward and reverse directions40. This allows the model to leverage both past and future context when making predictions, which is particularly advantageous in applications such as ecological forecasting and hydrological modeling where dependencies may not be strictly unidirectional41. The outputs of the forward and backward LSTM layers are concatenated and passed to a fully connected layer to generate the final prediction.

LSTM model architecture for Chl-a forecasts

The architecture of our chlorophyll-a prediction model is based on a BiLSTM neural network and consists of the following components in order: an input layer, a BiLSTM hidden layer, a dropout layer, a fully connected LSTM output layer, a second dropout layer, a flattening and batch normalization step, and a final dense layer, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Prior to model training, each regional chlorophyll-a time series was normalized to a 0–1 scale (min–max normalization) to stabilize the optimization. To frame the forecasting problem for the LSTM, we employed a sliding window approach: the network uses a sequence of N past observations to predict the next week’s chlorophyll-a value. We explored a range of window lengths from N = 4 to N = 20 and found the optimal length to be N = 12 weeks based on minimizing validation error. Thus, for each region, the LSTM takes the chlorophyll-a values from the previous 12 weeks as input features and outputs a prediction for week 13. Then, data points from weeks 1–13 will be used to predict the 14th week’s value and so on, allowing the model to extract patterns amongst the sequences. Using this windowing procedure on the training portion of each time series yielded approximately 1,015 training samples (input-output pairs) per region. The final shape of the input was 1015 × 12 × 1 (# of samples, # of timesteps, # of observations per timestep to predict).

This input sequence is passed to a hidden layer of bidirectional LSTM units, which enables the model to learn temporal dependencies in both forward and reverse directions. Such bidirectional encoding has been shown to improve predictive performance in environmental time series forecasting tasks, as it allows the model to consider both preceding and succeeding context in the sequence when learning feature representations40.

Following the BiLSTM layer, a dropout layer is applied to prevent overfitting by randomly deactivating a fraction of neurons during training. Dropout has been widely used in deep learning models for regularization, as it reduces co-adaptation of neurons and improves generalization on unseen data42. The output is then passed to an LSTM layer, which learns non-linear relationships among the data with context from past and future data points from the BiLSTM layer. This is followed by a second dropout layer, which further enhances model robustness during training.

To prepare the final prediction, the output is flattened, and then subjected to batch normalization. Batch normalization accelerates training and improves stability by reducing internal covariate shift and maintaining mean and variance consistency across batches43. The normalized vector is passed to a final dense, fully-connected output layer that produces a single list of values: the one-week-ahead forecast of chlorophyll-a concentration.

Model training was conducted using the Adam optimizer, which adaptively adjusts the learning rate for each parameter based on first- and second-order moment estimates. Adam has demonstrated faster convergence and better performance compared to conventional stochastic gradient descent in time series modeling44. An early stopping criterion based on validation loss was employed to prevent overfitting and to determine the optimal number of training epochs. Additionally, 15% of the training data was withheld as a validation set to guide model selection and hyperparameter tuning. The number of BiLSTM units, learning rate, batch size, and number of epochs were optimized independently for each region using a Tree-Parzen Estimator approach for hyperparameter optimization45.

Model training was performed separately for the lower, middle, and upper Bay datasets, resulting in three region-specific LSTM models. Each model was trained on its normalized training set until convergence (with early stopping to avoid overfitting) and then applied to generate predictions over the 15% testing period (approximately the last 181 weeks of data for each region, spanning 2017–2020). The denormalized LSTM predictions were compared to the true chlorophyll-a values to compute the same error metrics as for the ARIMA and TBATS models. These error metrics on the test set, reported in Table 1, allow a direct performance comparison across all models.

All computations for the LSTM modeling were carried out in Python. The Keras and TensorFlow46 libraries were used for building and training the neural network, while data handling and analysis of results were performed with pandas and NumPy. The overall workflow—from data preprocessing and model training to forecasting and evaluation—was integrated to ensure that each model was evaluated on an identical time period and under the same error metric definitions.

Results

Forecast accuracy

The LSTM model achieved the highest predictive accuracy for chlorophyll-a across all three regions of Chesapeake Bay. Table 1 summarizes the out-of-sample error metrics for each model and region, including Mean Error (ME), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). In every region, the LSTM’s errors were substantially lower than those of the ARIMA and TBATS models. Notably, the LSTM yielded the lowest RMSE values (e.g., 0.121 in the upper Bay, 0.155 in the middle Bay, 0.199 in the lower Bay), indicating superior overall accuracy. By contrast, the ARIMA models produced the highest errors on all metrics, while the TBATS models performed intermediately. The relatively low MAPE values under 15% for the LSTM further indicate its strong predictive performance.

Although the ARIMA models had weaker forecast accuracy, diagnostic checks confirmed that they captured the broad seasonal signal present in the data. A Ljung–Box test (with lag equal to twice the dominant seasonal period) showed no significant autocorrelation in the ARIMA forecast residuals (p > 0.05)47. This result implies that each ARIMA model accounted for the primary seasonality in its respective time series, even though it failed to predict many of the higher-frequency fluctuations and extremes. Overall, the error analysis in Table 1 identifies the LSTM as the most effective model for forecasting chlorophyll-a, consistently outperforming the statistical approaches.

Predicted Chlorophyll-a dynamics

The superior performance of the LSTM is also evident when comparing the time-series predictions against observed chlorophyll-a values. Figures 5, 6 and 7 illustrate the observed and model-predicted chlorophyll-a concentrations over time for the lower, middle, and upper Bay regions, respectively. The ARIMA forecasts generally follow the seasonal oscillations of chlorophyll-a (capturing, for instance, annual spring and summer peaks), but they tend to severely underestimate the magnitude of those peaks and miss many of the short-term fluctuations. In particular, ARIMA-predicted curves are smoother and fail to reproduce sudden spikes or drops in chlorophyll-a, indicating that this model struggles with the complex, non-linear variability present in the data.

The TBATS model offers some improvement over ARIMA. TBATS predictions more closely conform to the overall seasonal patterns and moderately changing seasonality of the chlorophyll-a time series. This is consistent with the TBATS framework’s capacity to handle multiple seasonal periods and time-varying seasonal strength. However, TBATS still does not fully capture the amplitude of high-frequency changes – for example, it often underestimates extreme chlorophyll-a surges and does not entirely track the timing of rapid declines.

In contrast, the LSTM predictions align very closely with the observed chlorophyll-a dynamics in all regions. The LSTM model closely reproduces the general upward and downward seasonal trends. Sudden algal bloom events reflected in the observed data are mirrored by corresponding spikes in the LSTM forecasts, and short-term drops in chlorophyll-a are similarly well captured. However, the magnitude of such peaks are often underrepresented, and some peaks are missed, such as the last downward spike in the Upper Region in Fig. 7.

The visual comparisons in Figs. 5, 6 and 7 corroborate the quantitative error metrics: the LSTM’s ability to learn complex temporal patterns allows it to anticipate both gradual seasonal variations and abrupt changes that the traditional statistical models largely miss. The close agreement between observed and LSTM-predicted values reinforces the conclusion that the LSTM approach provides the most reliable chlorophyll-a forecasts among the models tested.

Discussion

LSTM and statistical models comparison

This study set out to develop a robust regression model for forecasting chlorophyll-a levels in different regions of Chesapeake Bay, with the ultimate goal of improving water quality monitoring. Traditional time-series models such as ARIMA and TBATS are widely used for environmental forecasting, especially when seasonal cycles are present48. However, these statistical models have notable limitations when applied to very long and complex time series with multiple, evolving seasonal patterns. Our results demonstrate that a deep learning approach can overcome some of these limitations. By leveraging an LSTM neural network, we achieved substantially better predictive performance compared to the ARIMA and TBATS models, indicating that the LSTM could learn the Bay’s complex spatiotemporal chlorophyll-a dynamics more effectively.

Across all three Bay regions, the LSTM consistently yielded the lowest forecast errors, outperforming the benchmark models by significant margins. The LSTM’s RMSE values were approximately 16–40% lower than those of the corresponding ARIMA models, and up to ~ 25% lower than those of the TBATS models for the same data (Table 1). This improvement in accuracy is also reflected in the MAE and MAPE metrics. Visually, the LSTM predictions tracked the observed chlorophyll-a fluctuations far more closely than ARIMA or TBATS, which often lagged or dampened the true signal (Figs. 3, 4 and 5). The ARIMA models appeared to capture only the broad seasonal trend and failed to predict shorter-term variability and extreme algal bloom events. The TBATS models performed somewhat better—likely because TBATS can incorporate multiple seasonal components and allow seasonal patterns to change over time48—but they still could not fully replicate the magnitude of chlorophyll-a surges or dips. The LSTM’s superior performance can be attributed to its ability to model non-linear relationships and memory of long-term dependencies in the data, enabling it to represent both regular seasonal cycles and irregular events. In essence, the LSTM learned a more complete picture of the underlying dynamics driving chlorophyll-a changes, including interactions and temporal lags that the simpler models could not accommodate. Another advantage is that machine learning models do not require strong a priori assumptions about the data generation process; unlike ARIMA or TBATS, which are constrained by specific statistical formulations, the LSTM can flexibly learn patterns directly from the data. Apart from the need for computational resources, there are relatively few barriers to deploying such models, making them accessible tools for environmental scientists and resource managers The remaining discrepancy in peak magnitude and number of peaks captured by the LSTM can be attributed to a few factors. First, the training objective of the LSTM minimizes overall error (e.g. mean squared error), which biases the model toward accurately predicting average behavior rather than rare, high-magnitude events. Such spikes, especially extreme ones, occur infrequently and often vary by region, and are therefore underrepresented in the training set, limiting the model’s ability to learn temporal patterns of extreme peaks.

From an ecological perspective, sudden surges in chlorophyll-a are typically associated with episodic events like nutrient runoff from storms, seasonal hypoxia, or short-term stratification that promote algal blooms. These drivers are not easily detectable from chl-a time series alone, especially when the model only receives univariate inputs. The LSTM, despite its memory capabilities, lacks access to the broader environmental context—such as rainfall events, river discharge, water temperature, or nutrient loads—which are known to play a critical role in triggering phytoplankton blooms.

Thus, to improve the model’s ability to capture peaks, future iterations could incorporate multivariate inputs that include relevant physical and biogeochemical variables. Additionally, specialized loss functions (e.g. quantile loss or asymmetric penalties) may help prioritize accurate forecasting of extreme events. Augmenting the training dataset with synthetic or oversampled high-peak events could also improve the model’s sensitivity to outliers.

LSTM accuracy by Bay region comparison

Beyond pure accuracy, the LSTM approach offers additional practical advantages for water quality forecasting. One key benefit is scalability: once trained, the LSTM model can be retrained or adapted to incorporate new data streams or applied to different locations, provided sufficient historical data are available. In our study, we trained separate LSTM models for the lower, middle, and upper Bay, allowing each to recognize the unique chlorophyll-a patterns of that region. Differences in the seasonal, physical, and biogeochemical properties of each region can further explain the results in Table 1.

The upper Chesapeake Bay is heavily influenced by freshwater input—predominantly from the Susquehanna River—which drives nutrient loading, turbidity, and phytoplankton bloom dynamics. Interannual variability in freshwater discharge influences salinity stratification and the location of phytoplankton accumulation zones along the estuary, leading to corresponding shifts in chlorophyll a concentrations49. Large rain events or tropical storms—such as Tropical Storm Lee in 2011—can significantly increase discharge, delivering pulses of nutrients and sediments that stimulate sudden blooms in the upper Bay50. This region is also characterized by turbid, estuarinetype (“Case-2”) waters with high colored dissolved organic matter (CDOM) and sediments, reducing light penetration and complicating both measurement and modeling of chlorophylla51. These optically complex and highly variable conditions, combined with episodic pulse events from storms, pose significant challenges for accurate forecasting, resulting in the highest RMSE in the upper Bay.

The middle Bay experiences moderate nutrient input and salinity (~ 5–15 ppt), with seasonal stratification that enhances phytoplankton growth, and subjects the waters to mixing and dilution49. Biogeochemical modeling indicates that peak blooms often occur in middle Bay regions due to the convergence of optimal nutrient, light, and transport conditions20. Yet this region remains influenced by residual CDOM and particulate matter, producing intermediate clarity and moderate optical complexity51. Consequently, the LSTM achieves better predictive performance than in the upper Bay but still struggles to fully resolve fluctuating blooms, yielding intermediate RMSE.

In contrast, the lower Bay exhibits deeper, clearer, polyhaline waters with lower nutrient concentrations and greatly reduced turbidity, approximating “Case-1” optical conditions more akin to coastal ocean waters51. Nutrient inputs are diluted by mixing with Atlantic water and river plumes are seaward of central Bay. Such conditions yield relatively stable chlorophylla distributions, slower bloom growth, and more persistent stratification and phytoplankton dynamics49. These more linear, less noisy environmental signals enable the LSTM model to capture trends robustly, minimizing error. Thus, lower variability in chl-a concentration drivers and clearer optics likely underlie the lowest RMSE in this region.

The gradient of RMSE values (upper > middle > lower Bay) mirrors the estuarine salinity and clarity gradient. In the upper Bay, episodic nutrient pulses, strong variability in freshwater discharge, and high turbidity generate complex, non-linear chlorophylla responses that are poorly constrained by only a univariate time series. MidBay has moderate complexity and more spatial coherence in bloom dynamics, yielding better but still imperfect predictions. In the lower Bay, mixing with ocean water, reduced turbidity, and stable hydrodynamics produce more predictable, smoother chlorophylla dynamics. This spatial gradient in LSTM performance underscores the importance of regional environmental complexity in shaping forecasting accuracy and highlights the need for tailored modeling approaches across different estuarine zones.

Comparison with other studies

Table 2 shows the performance of our proposed LSTM models compared with other closely related chl-a forecasting models based on machine learning methods. Few studies testing LSTMs in estuarine environments exist, so we included comparisons to freshwater and coastal marine environments as a proxy benchmark. Where necessary, RMSE values reported as mg/L were converted to mg/m3 using the factor 1 mg/L = 1000 mg/m3, assuming standard water density. If models were applied to multiple sites/regions, a range of the minimum and maximum RMSE values was provided.

The comparative table highlights that our study achieved significantly lower RMSE values (mg / m^3) than prior deep learning efforts in forecasting chlorophyl-a. In particular, our model achieves a strong balance between longer-term forecasting and low prediction error in an estuarine setting. While some studies (e.g. Barzegar et al., Cen et al.) report lower RMSE values, their prediction windows are much shorter—ranging from 6 h to 5 days—making the forecasting task inherently easier. Lin et al., which is most similar to our study in that it also focuses on estuaries, reports much higher RMSEs (1.14–12.05 mg/m3) for 2-week predictions. In comparison, our 1-week horizon maintains low RMSEs (0.121–0.199 mg/m3), highlighting superior model stability over extended timeframes. This suggests our model captures longer-term ecological patterns in complex estuarine systems more effectively than prior efforts, making it a valuable contribution to operational water quality forecasting.

One key reason for improved performance could be training models on regional data versus the entire Bay. This allowed region-specific LSTMs to better capture local chlorophyll-a dynamics and reduce noise introduced by spatial heterogeneity. Additionally, we used 23 years’ worth of chlorophyll-a data in training/testing the model—substantially more than every study mentioned in the table—which allowed the LSTM model to learn from a wide range of temporal patterns, rare events, and interannual variability, leading to more robust and generalizable predictions. Finally, our use of hyperparameter tuning helped to optimize the model architecture and improve the network’s ability to learn from the data. Interestingly, the choice of a BiLSTM layer followed by a normal LSTM layer (which does not seem to be tested in previous literature) implies that all other combinations of layers (namely: 2 consecutive BiLSTM layers, 2 consecutive LSTM layers, or an LSTM layer followed by a BiLSTM) performed worse in comparison. The optimal analysis sequence can likely be explained as: the first BiLSTM extracts context from both past and future data points, then a normal LSTM processes this enriched representation of the data. This suggests that a hybrid pipeline of a BiLSTM followed by an LSTM provides a unique advantage for applications to time series data and forecasting.

Future direction

There are several avenues for future research to build on these results. First, incorporating additional predictor variables may further enhance forecast accuracy. Chlorophyll-a dynamics are influenced not only by their past values but also by external factors such as nutrient loading (nitrogen and phosphorus inputs), river discharge, temperature, and light availability. Multi-variate LSTM models or hybrid approaches could integrate these drivers to improve predictions and provide mechanistic insights. For instance, a model that ingests both historical chlorophyll-a and nutrient concentration data might better anticipate algal blooms triggered by agricultural runoff or sewage discharges. Second, exploring different deep learning architectures (e.g., sequence-to-sequence models or attention-based networks) could be valuable, as they might capture long-term trends or periodicities differently than a standard LSTM. Finally, extending the forecasting horizon beyond one week and providing uncertainty estimates (prediction intervals) could potentially increase the model’s utility for decision-making in water resource management.

The Chesapeake Bay’s health is of great concern given its ecological significance and the fact that millions of people depend on its waters. Declines in water quality, manifested through symptoms like excessive chlorophyll-a, harmful algal blooms, and hypoxia, can have cascading effects on fisheries, recreation, and drinking water safety in the region. Predictive models such as the LSTM developed in this study can serve as early warning systems for emerging water quality issues. For example, if a model forecasts a sharp rise in chlorophyll-a for the coming weeks, managers could proactively investigate and mitigate nutrient sources or consider preventative aeration in susceptible areas. In a broader sense, our work demonstrates that modern machine learning techniques can complement traditional environmental monitoring, offering enhanced capability to detect complex patterns and changes in ecosystem behavior.

Conclusion

This study presents a novel application of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to forecast chlorophyll-a concentrations in the Chesapeake Bay, marking the first use of deep learning for harmful algal bloom (HAB) prediction in this estuarine system. By incorporating over two decades of satellite and in-situ observations, the model captures long-term temporal dynamics while maintaining strong generalizability across spatially diverse regions. Achieving low RMSE values (0.121–0.199 mg/m3) over a practical one-week forecasting window, our approach offers a promising framework for data-driven, anticipatory water quality management in dynamic coastal environments.The approach presented here can be generalized to other regions, other types of water bodies (lakes, rivers, marine waters, etc.), and water quality indicators, suggesting that deep learning models will play an increasingly important role in sustaining water resources and protecting vital aquatic ecosystems like the Chesapeake Bay.

Data availability

All observational data that support the findings of this study are publicly available, and can be found at this site: https://seabass.gsfc.nasa.gov/timeseries/.

References

Du Plessis, A. Persistent degradation: Global water quality challenges and required actions. One Earth. 5, 129–131 (2022).

Wolf, J. et al. Burden of disease attributable to unsafe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene in domestic settings: A global analysis for selected adverse health outcomes. Lancet 401, 2060–2071 (2023).

Boyer, J. N., Kelble, C. R., Ortner, P. B. & Rudnick, D. T. Phytoplankton bloom status: Chlorophyll a biomass as an indicator of water quality condition in the Southern estuaries of florida, USA. Ecol. Indic. 9, S56–S67 (2009).

Mineeva, N. M. & Makarova, O. S. Chlorophyll content as an indicator of the modern (2015–2016) trophic state of Volga river reservoirs. Inland. Water Biol. 11, 367–370 (2018).

Busari, I., Sahoo, D. & Jana, R. B. Prediction of chlorophyll-a as an indicator of harmful algal blooms using deep learning with bayesian approximation for uncertainty assessment. J. Hydrol. 630, 130627 (2024).

Wang, H. & Convertino, M. Algal bloom ties: Systemic biogeochemical stress and Chlorophyll-a shift forecasting. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110760 (2023).

Blix, K. & Eltoft, T. Machine learning automatic model selection algorithm for oceanic Chlorophyll-a content retrieval. Remote Sens. 10, 775 (2018).

Harding, L. W. et al. Long-term trends, current status, and transitions of water quality in Chesapeake Bay. Sci. Rep. 9, 6709 (2019).

Zhang, Q. & Blomquist, J. D. Watershed export of fine sediment, organic carbon, and chlorophyll-a to Chesapeake bay: Spatial and Temporal patterns in 1984–2016. Sci. Total Environ. 619–620, 1066–1078 (2018).

Kogekar, A. P., Nayak, R. & Pati, U. C. Forecasting of Water Quality for the River Ganga using Univariate Time-series Models. in 8th International Conference on Smart Computing and Communications (ICSCC) 52–57 (IEEE, Kochi, Kerala, India, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSCC51209.2021.9528216

Katimon, A., Shahid, S. & Mohsenipour, M. Modeling water quality and hydrological variables using ARIMA: A case study of Johor river, Malaysia. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 4, 991–998 (2018).

Myronidis, D., Ioannou, K., Fotakis, D. & Dörflinger, G. Streamflow and hydrological drought trend analysis and forecasting in Cyprus. Water Resour. Manag. 32, 1759–1776 (2018).

Su, J., Lin, Z., Xu, F., Fathi, G. & Alnowibet, K. A. A hybrid model of ARIMA and MLP with a grasshopper optimization algorithm for time series forecasting of water quality. Sci. Rep. 14, 23927 (2024).

Glibert, P. M. Eutrophication, harmful algae and biodiversity — Challenging paradigms in a world of complex nutrient changes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 124, 591–606 (2017).

Al Shehhi, M. R. & Kaya, A. Time series and neural network to forecast water quality parameters using satellite data. Cont. Shelf Res. 231, 104612 (2021).

Alnahit, A. O., Mishra, A. K. & Khan, A. A. Stream water quality prediction using boosted regression tree and random forest models. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 36, 2661–2680 (2022).

Deng, T., Chau, K. W. & Duan, H. F. Machine learning based marine water quality prediction for coastal hydro-environment management. J. Environ. Manag. 284, 112051 (2021).

Yussof, F. N., Maan, N. & Md Reba, M. N. LSTM networks to improve the prediction of harmful algal blooms in the West Coast of Sabah. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 7650 (2021).

Cen, H. et al. Applying deep learning in the prediction of Chlorophyll-a in the East China sea. Remote Sens. 14, 5461 (2022).

Eze, E., Kirby, S., Attridge, J. & Ajmal, T. Time series Chlorophyll-A concentration data analysis: A novel forecasting model for aquaculture industry. in The 7th International Conference on Time Series and Forecasting 27 (MDPI, 2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2021005027

Eze, E., Kirby, S., Attridge, J. & Ajmal, T. Aquaculture 4.0: Hybrid neural network multivariate water quality parameters forecasting model. Sci. Rep. 13, 16129 (2023).

Zheng, L. et al. Prediction of harmful algal blooms in large water bodies using the combined EFDC and LSTM models. J. Environ. Manag. 295, 113060 (2021).

Barzegar, R., Aalami, M. T. & Adamowski, J. Short-term water quality variable prediction using a hybrid CNN–LSTM deep learning model. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 34, 415–433 (2020).

Lin, J. et al. Temporal prediction of coastal water quality based on environmental factors with machine learning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 11, 1608 (2023).

Gachloo, M. et al. Using machine learning models for Short-Term prediction of dissolved oxygen in a microtidal estuary. Water 16, 1998 (2024).

Zhu, X. et al. An ensemble machine learning model for water quality Estimation in coastal area based on remote sensing imagery. J. Environ. Manag. 323, 116187 (2022).

Shin, Y. et al. Prediction of Chlorophyll-a concentrations in the Nakdong river using machine learning methods. Water 12, 1822 (2020).

Savoy, P. & Harvey, J. W. Predicting daily river chlorophyll concentrations at a continental scale. Water Resour. Res. 59, eWR034215 (2022).

Gobler, C. J., Burson, A., Koch, F., Tang, Y. & Mulholland, M. R. The role of nitrogenous nutrients in the occurrence of harmful algal blooms caused by cochlodinium Polykrikoides in new York estuaries (USA). Harmful Algae. 17, 64–74 (2012).

Egerton, T. A., Morse, R. E., Marshall, H. G. & Mulholland, M. R. Emergence of algal blooms: the effects of short-term variability in water quality on phytoplankton abundance, diversity, and community composition in a tidal estuary. Microorganisms 2, 33–57 (2014).

McGowan, J. A. et al. Predicting coastal algal blooms in Southern California. Ecology 98, 1419–1433 (2017).

Goodrich, S., Canfield, K. N. & Mulvaney, K. Expert insights on managing harmful algal blooms. Front. Freshw. Sci. 2, 1452344 (2024).

Stroming, S., Robertson, M., Mabee, B., Kuwayama, Y. & Schaeffer, B. Quantifying the human health benefits of using satellite information to detect cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms and manage recreational advisories in U.S. lakes. GeoHealth 4, eGH000254 (2020).

Liu, C., Chen, Y., Zou, L., Cheng, B. & Huang, T. Time-Lag effect: River algal blooms on multiple driving factors. Front. Earth Sci. 9, 813287 (2022).

Magnuson, A., Harding, L. W., Mallonee, M. E. & Adolf, J. E. Bio-optical model for Chesapeake Bay and the middle Atlantic bight. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 61, 403–424 (2004).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Gers, F. A., Schmidhuber, J. & Cummins, F. Learning to forget: Continual prediction with LSTM. Neural Comput. 12, 2451–2471 (2000).

Zhi, W., Appling, A. P., Golden, H. E., Podgorski, J. & Li, L. Deep learning for water quality. Nat. Water. 2, 228–241 (2024).

Kratzert, F. et al. Toward improved predictions in ungauged basins: Exploiting the power of machine learning. Water Resour. Res. 55, 11344–11354 (2019).

Schuster, M. & Paliwal, K. K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal. Process. 45, 2673–2681 (1997).

Ghasemlounia, R., Gharehbaghi, A., Ahmadi, F. & Saadatnejadgharahassanlou, H. Developing a novel framework for forecasting groundwater level fluctuations using Bi-directional long Short-Term memory (BiLSTM) deep neural network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 191, 106568 (2021).

Srivastava, N. et al. A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 1929–1958 (2014).

Ioffe, S. & Szegedy, C. Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1502.03167 (2015).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1412.6980 (2014).

Bergstra, J., Bardenet, R., Bengio, Y. & Kégl, B. Algorithms for hyper-parameter optimization. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Shawe-Taylor, J., Zemel, R., Bartlett, P., Pereira, F. & Weinberger, K. Q.) vol. 24 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2011).

Abadi, M. et al. TensorFlow: A system for large-scale machine learning. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1605.08695 (2016).

Hyndman, R. J. & Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice. 2nd Ed. (OTexts, 2018).

De Livera, A. M., Hyndman, R. J. & Snyder, R. D. Forecasting time series with complex seasonal patterns using exponential smoothing. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 106, 1513–1527 (2011).

Zhang, X., Roman, M., Kimmel, D., McGilliard, C. & Boicourt, W. Spatial variability in plankton biomass and hydrographic variables along an axial transect in Chesapeake Bay. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 111, 2005JC003085 (2006).

Harding, L. W. et al. Variable Climatic conditions dominate recent phytoplankton dynamics in Chesapeake Bay. Sci. Rep. 6, 23773 (2016).

Rose, K. C., Neale, P. J., Tzortziou, M., Gallegos, C. L. & Jordan, T. E. Patterns of spectral, spatial, and long-term variability in light Attenuation in an optically complex sub‐estuary. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, (2019).

Acknowledgements

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SG and SG wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all figures and tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, S., Gupta, S. Time series forecasting of chlorophyll-a concentrations in the Chesapeake Bay. Sci Rep 15, 30877 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16352-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16352-3