Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X-linked recessive disorder characterized by progressive muscular dystrophy, ultimately leading to paralysis and death from cardiac failure and/or respiratory insufficiency. Preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic disorders (PGT-M) has proven effective in helping families with complete pedigrees carrying DMD mutations to produce unaffected offspring. This study was designed to evaluate the feasibility of using nanopore sequencing as an effective PGT-M technique for DMD, particularly in cases involving de novo mutations or incomplete pedigrees that cannot be analyzed using second-generation sequencing (SGS) alone. Nanopore sequencing was performed on two DMD female carriers. The precise breakpoints of the DMD mutations were detected with nanopore sequencing, and haplotypes were constructed based on flanking single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Haplotype linkage analyses were subsequently performed by comparing parental SNPs with embryonic SNPs to determine whether the embryos inherited the maternal DMD mutation-carrying chromosome. We successfully identified disease-free euploid embryos for both pedigrees. These results were consistent with the data obtained using SGS and amniocentesis. Our results establish nanopore sequencing as a clinically applicable methodology for preimplantation haplotype linkage analysis in PGT-M for DMD, particularly valuable for families with non-informative pedigrees where traditional linkage analyses are not feasible. This finding is crucial for reducing the propagation of DMD in the population through the application of nanopore sequencing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is an X-linked recessive disease that affects approximately 1 in 5,000 newborn males1,2,3. The earliest symptoms, including progressive muscle weakness, difficulties with jumping and climbing stairs, frequent falls, and an unusual waddling gait, usually appear at approximately 2–3 years of age1,4,5. The majority of patients with DMD become wheelchair-dependent around the age of 12 years owing to progressive muscle tissue and function loss and require assisted ventilation by the age of 20 years1,4. Most patients die of cardiac failure and/or respiratory insufficiency at approximately 20–40 years of age1,4. DMD is caused by mutations in the DMD gene, which is the largest known gene in the human genome6. This gene is located on chromosome Xp21 and contains 79 exons6,7. A wide range of mutations have been identified in patients with DMD, with deletions accounting for approximately 60–70% of cases, duplications accounting for 5–15%, and point mutations or other small rearrangements accounting for the remaining 20%4. Accurate characterization of mutations in the DMD gene and utilizing precise diagnostic tools are crucial for effective genetic counseling and personalized medicine6. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) is generally used for DMD diagnosis owing to the convenience of commercially available kits and the high frequency of deletions/duplications4. Multiple PCR and second-generation sequencing (SGS) approaches have also been used to identify mutations in the DMD gene2. These techniques are often used in combination to capitalize on their respective strengths and mitigate their individual limitations2. As is common with most monogenic disorders, there is currently no effective treatment for DMD. Several strategies, including gene addition, exon skipping, stop codon readthrough, and genome editing, have been developed based on the type of mutation to restore the expression of partially functional dystrophin proteins1. However, these treatments cannot prevent the continuous loss of muscle tissue and function that ultimately leads to premature death1. Additionally, some issues still need to be addressed before these therapies can be widely used in clinical applications8.

Preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic disorders (PGT-M) has been widely used to help couples with monogenic mutations to produce unaffected offspring. PGT-M for DMD was initially based on sex selection, which resulted in only 50% of the available embryos being suitable for transfer9. Direct mutation analysis by triplex-nested PCR was subsequently used in PGT-M for DMD, resulting in 75% of embryos being viable for transfer10. However, in families with deletion-type mutations, it is not possible to distinguish female carriers from non-carrier female embryos using these strategies11. SGS is currently capable of providing direct information at a single-base resolution, allowing haplotype linkage analysis using single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)9,12. This can aid in the identification of female carrier embryos in families with deletion-type mutations, ultimately improving the accuracy of PGT-M9. However, the current PGT-M based on SGS cannot provide an effective PGT technique for monogenic disorders that involve de novo mutations, incomplete pedigrees, or disease-causing genes located in a region close to telomere13.

Recently, there have been notable improvements in third-generation sequencing (TGS) technology in terms of read length, cost, and accuracy. Oxford Nano and PacBio are two commonly used instruments for TGS. Oxford Nanopore sequencing offers direct and long read lengths with simple library preparation, minimal capital cost, and short user time, on a small handheld platform14,15. This technology is extensively used in PGT for structural rearrangements (PGT-SR) and aneuploidy (PGT-A)15,16,17,18,19,20,21. PacBio single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing was initially applied to PGT-M for maple syrup urine disease22. In a recent study, PacBio SMRT sequencing was used to detect the mutation sites involved in beta-thalassemia (β-thalassemia), as well as multiple consecutive SNP markers located nearby, which facilitated efficient haplotype linkage analysis in PGT-M for β-thalassemia13. To date, there have been no reports on the applicability of nanopore sequencing for DMD during PGT-M cycles.

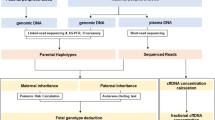

The present study assesses the feasibility of using nanopore sequencing in PGT-M for DMD. The accuracy of the nanopore sequencing results was confirmed using an SGS-based method, which was further validated by amniocentesis. Using nanopore sequencing, we identified a set of informative heterozygous SNPs in DMD female carriers, which were then used for haplotype linkage analyses. Ultimately, the couples were able to transfer DMD disease-free euploid embryos, and the outcomes of invasive prenatal diagnosis were within normal parameters. Both pregnancies are currently progressing as expected.

Results

SGS-based mapping of DMD mutations

In pedigree 1, patient 1 was identified with a duplication of exons 15–17 in the DMD gene by MLPA analysis (Fig. 1A, B). Further investigation of the family indicated that the DMD mutation was inherited from the patient’s mother (Fig. 1A, B). In pedigree 2, the proband YZJ was diagnosed as a DMD patient (Fig. 1C). Subsequently, MLPA analysis was performed on genomic DNA samples from the family to identify DMD mutations, revealing a deletion of exons 3–9 in both the proband and her mother (Fig. 1C, D).

MLPA reveals the DMD gene mutation in the pedigrees. (A) Genealogical tree of pedigree 1. (B) DMD gene mutation confirmed by MLPA. In pedigree 1, a duplication of exons 15–17 was detected in both patient 1 and her mother. (C) Genealogical tree of pedigree 2. (D) In pedigree 2, MLPA analysis revealed a deletion of exons 3–9 in both the proband and her mother.

In patient 1, five blastocysts (E1–5) were obtained and biopsied for whole-genome amplification (WGA). Copy number variation (CNV) analysis revealed that embryos E3, E4, and E5 exhibited normal ploidy (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1). Two embryos (E1 and E2) with abnormal chromosomes were identified (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1). For patient 2, 12 embryos were examined. Normal ploidy was confirmed in five embryos: E2, E5, E8, E10, and E12 (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1). Five embryos (E3, E4, E6, E7, and E11) exhibited abnormal chromosomes, while two mosaic embryos (E1 and E9) were detected (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1).

In the first pedigree, SNP information for all family members and embryos was acquired using SGS. Following the removal of low-quality SNPs, we successfully identified a number of reliable SNPs that were located within a 1 Mbp range of the DMD gene (Fig. 2A). Haplotype linkage analysis was conducted by comparing the coincident-phasing SNPs of patient 1 with those of the embryos (Fig. 2A). According to haplotype linkage analysis, embryos E2, E4, and E5 carried a heterozygous duplication in exons 15–17, whereas embryos E1 and E3 did not inherit the maternal DMD mutation (Fig. 2A; Table 1). In a similar manner, haplotype linkage analysis was performed by comparing the coincident-phasing SNPs of patient 2 and embryos, both obtained from SGS, revealing that five embryos (E3, E4, E5, E6, and E12) did not inherit the maternal DMD mutation (Fig. 2B; Table 2). Complete SNP information for embryo E7 of patient 2 could not be obtained owing to a high allele dropout (ADO) rate during WGA, making it impossible to ascertain whether the embryo inherited the maternal DMD mutation.

Allelic haplotype mapping to identify the carrier status of the DMD gene mutation in the embryos. SGS was used to sequence SNPs located within a 1 Mbp range of the DMD gene for all family members and embryos in both pedigrees. (A) In pedigree 1, haplotype linkage analysis indicated that embryos E2, E4, and E5 carried a heterozygous duplication in exons 15–17, whereas embryos E1 and E3 did not inherit the maternal DMD mutation. (B) In pedigree 2, five embryos (E3, E4, E5, E6, and E12) did not inherit the maternal DMD mutation; however, the carrier status of embryo E7 could not be determined due to ADO during WGA. The remaining embryos exhibited a heterozygous deletion in exons 3–9.

Nanopore sequencing-based mapping of DMD mutations

Libraries were constructed using genomic DNA extracted from the peripheral blood of patients 1 and 2. Nanopore sequencing was performed using a PromethION 48 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) with a single sample loaded onto one flow cell. After data filtering, we obtained 97.4 Gb of data for patient 1. The mean read length was 19,764 bp, and the N50 was 26,288 bp. The average sequencing depth for the whole genome was 32.47×. For patient 2, 67 Gb of data was collected, with a mean read length of 17,429 bp and an N50 of 20,000 bp. The average sequencing depth for the whole genome was 22.33×.

SNPs located within a 1 Mbp range upstream and downstream of the DMD mutation on the same read or contig were classified as belonging to the same haplotype, typically referred to as hap1. SNPs that were not linked to the DMD mutation were grouped into another haplotype, usually referred to as hap2. A total of 1,085 reliable SNPs were identified for patient 1 and 427 reliable SNPs for patient 2 within the 1 Mbp range to perform phasing for the DMD mutation located on chromosome X. The SNP haplotypes constructed using the nanopore sequencing data were consistent with those obtained from SGS (comparing Fig. 3A with Fig. 2A, and Fig. 3B with Fig. 2B). Haplotype linkage analysis based on nanopore sequencing data indicated that in patient 1, embryos E1 and E3 did not inherit the maternal DMD mutation (Fig. 3A), while in patient 2, embryos E3, E4, E5, E6, E7, and E12 did not inherit the maternal DMD mutation (Fig. 3B). The Integrative Genomics Viewer graphs display the breakpoints of the DMD mutations on chromosome X, as determined using the GRCh37 reference genome (Fig. 4A–D). The breakpoints for patient 1 identified by nanopore sequencing were located at chrX:32,562,666 and chrX:32,591,938 (Fig. 4A, B), whereas for patient 2, the breakpoints were found at chrX:32,711,038 and chrX:32,904,034 (Fig. 4C, D).

Resolving the carrier status of the DMD gene mutation in the embryos by nanopore sequencing mapping. SNPs haplotyping were conducted successfully using SNPs obtained by nanopore sequencing and embryonic SNPs obtained through SGS. (A) In the case of patient 1, haplotype linkage analysis revealed that embryos E2, E4, and E5 inherited the maternal DMD mutation, while embryos E1 and E3 did not inherit it. (B) For patient 2, embryos E3, E4, E5, E6, E7, and E12 were found not to have inherited the maternal DMD mutation.

Nanopore sequencing mapping of the DMD gene mutation breakpoints. Nanopore sequencing was performed on a PromethION 48. (A, B) In the case of patient 1, the breakpoints identified by nanopore sequencing were located at chrX:32,562,666 and chrX:32,591,938. (C, D) For patient 2, the breakpoints were found at chrX:32,711,038 and chrX:32,904,034.

Validation of PGT-M results by prenatal diagnosis

Embryo E3, which did not carry the maternal DMD mutation and had normal ploidy, was a frozen day-5 blastocyst of Gardner’s grade 4CB. It was transferred to the uterus of patient 1 with informed consent, resulting in a singleton pregnancy. Amniocentesis was performed at 18–20 weeks of gestation. Prenatal diagnosis by MLPA confirmed the absence of large deletions or duplications in the 79 exons of the DMD gene, consistent with the findings obtained from SGS and nanopore sequencing (data not shown). Karyotype analysis based on chromosome G-banding revealed a non-pathogenic polymorphic pericentric inversion, 46,XN, inv(9)(p12q13), inherited from patient 1 (Supplementary Fig. S2). In pedigree 2, embryo E5 with Gardner’s grade 5BA, which did not carry the maternal DMD mutation and had normal ploidy, was transferred to the uterus of patient 2 with informed consent. MLPA analysis of genomic DNA from amniotic fluid cells also verified the lack of large deletions or duplications in the 79 exons of the DMD gene, aligning with the results from SGS and nanopore sequencing (data not shown). The pregnancy is currently ongoing. Postnatal follow-up will be conducted for both patients to confirm the consistency between the results of the PGT-M cycle, amniocentesis, and peripheral blood.

Discussion

In this study, we used nanopore sequencing to identify embryos free of DMD mutations from heterozygous carriers in PGT-M cycles. Using nanopore sequencing, we identified the breakpoints of the DMD mutations and established haplotypes using the flanking SNPs. Subsequently, we conducted haplotype linkage analyses with embryonic SNPs to ascertain whether the embryos had inherited the maternal DMD mutation-carrying chromosome. These findings were consistent with those obtained using the conventional SGS-based method and were further validated using an amniotic fluid test. This work highlights the value and practicality of using nanopore sequencing in the PGT-M for DMD, particularly for families unable to obtain haplotype analysis using SGS-based methods.

A major challenge in PGT-M is the occurrence of ADO during WGA. This is primarily caused by the limited amount of the initial DNA template, which is usually obtained from only 3–5 trophectoderm cells. ADO refers to the preferential amplification of one allele over another, or the complete amplification of one allele, whereas the other allele remains unamplified. This phenomenon can lead to an unsuccessful or inaccurate diagnosis, which in turn can result in false-positive or false-negative outcomes in PGT-M cycles. To reduce the impact of factors, such as ADO and sample contamination, it is commonly recommended to simultaneously conduct direct detection of mutation sites and haplotype linkage analysis. This strategy enables comprehensive assessment of genetic variations and ensures precise outcomes. Short tandem repeat (STR)-based haplotype linkage analysis is the conventional method in PGT-M cycles for DMD11. The inclusion of STR polymorphic markers in the analysis helps to validate the results and reduce the likelihood of misdiagnosis. However, STR-based haplotyping has certain limitations such as limited detection throughput, lengthy detection cycles, and a restricted number of STRs. The abundance of SNPs in the human genome makes them ideal genetic markers, and SNP-based linkage analysis can further minimize the risk of false negatives or false positives. SGS technology requires DNA fragmentation, and the read length range of commonly used SGS platforms is 50–150 bp. It is worth noting that SNPs typically occur every 300 bp in the human genome. Consequently, SGS cannot detect more than one SNP per DNA fragment, thereby lacking direct information on sequentially aligned SNPs. Furthermore, the information provided by individual SNPs is incomplete and relatively limited compared with that provided by a combination of consecutive SNPs. Therefore, when SGS technology is used for haplotype linkage analysis based on SNPs, a proband is typically required for clinical PGT-M cycles. In addition, SGS faces challenges in effectively handling unique scenarios, such as de novo mutations in families, incomplete family structures, and a multitude of homologous regions resulting from inbreeding. Furthermore, difficulties arise when dealing with a target gene located at the end of a chromosome.

Recently, there have been remarkable advancements in TGS technologies such as Oxford Nanopore sequencing and PacBio SMRT sequencing. These advancements have led to improvements in read length, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness. TGS offers several advantages over SGS: (i) TGS can generate long reads ranging from 10 to 60 kb with nanopore sequencing and 10 to 20 kb with SMRT sequencing, enabling direct haplotype construction in PGT-M, even in complex scenarios involving de novo mutations or incomplete pedigrees; (ii) TGS-based PGT-M requires only DNA samples from the couple, simplifying the workflow and reducing the invasiveness compared to SGS-based methods, which typically rely on extended family samples; (iii) TGS do not exhibit a preference for specific chromosomes or regions even when mutations are located in repetitive and GC-bias regions; (iv) TGS have been successfully employed to determine the sequence of full-length RNA transcripts, as well as to identify modifications in native DNA and RNA23.

Two studies have demonstrated the value and feasibility of PacBio SMRT sequencing in PGT-M cases13,22. Wu et al. utilized SMRT sequencing to develop a haplotyping method for direct sequencing the mutation sites associated with β-thalassemia, as well as consecutive SNP markers in close proximity13. This method guarantees the precision and effectiveness of haplotype construction while circumventing the need for proband acquisition13. Consequently, this method is anticipated to assist families with β-thalassemia facing challenges in haplotype construction through SGS13. Using nanopore sequencing, we identified a collection of informative heterozygous SNPs in two DMD female carriers. Subsequently, we successfully conducted haplotype linkage analyses by comparing these SNPs with embryonic SNPs obtained through SGS without relying on sequences from additional family members. The analyses helped to determine whether the embryos inherited the maternal DMD mutation. Our study demonstrates, for the first time, the feasibility of implementing nanopore sequencing in clinical PGT-M for DMD. These clinical studies provide robust evidence for the use of TGS technology as a powerful and effective tool for preimplantation haplotype linkage analysis during PGT-M cycles. This technology will help realize the aspiration of PGT-M for families that are unable to undergo SNP-based haplotyping using conventional SGS methods, thereby enabling them to have a healthy offspring.

Further retrospective and prospective studies are needed to validate the specificity and sensitivity of nanopore sequencing in PGT-M cycles. Additionally, optimization and standardization of the entire process are required to validate the clinical application of this method on a large scale. However, nanopore sequencing does have limitations. For instance, obtaining SNP information for embryos from WGA products using nanopore sequencing is challenging. Moreover, the cost of the entire nanopore sequencing workflow is a critical consideration for PGT centers in daily practice. Nevertheless, nanopore sequencing remains a potential tool for preimplantation haplotype linkage analysis in PGT-M for DMD, particularly in families lacking probands.

In this study, we employed nanopore sequencing for heterozygous carriers of the DMD mutation in PGT-M cycles. We successfully determined the precise breakpoints of the DMD mutations and established haplotypes using flanking SNPs, aided by nanopore sequencing and the GRCh37 reference genome. Following this, we performed haplotype linkage analyses with embryonic SNPs to ascertain whether the embryos had inherited the maternal mutation. Based on the results of CNV and haplotype linkage analyses, the couples were able to transfer disease-free euploid embryos, and the outcomes of invasive prenatal diagnosis were within normal parameters. Our study is the first to demonstrate the application of nanopore sequencing to clinical PGT-M for DMD. This concept offers a practical scheme for addressing the challenges associated with PGT-M for DMD mutations, particularly for families unable to obtain haplotype analysis using SGS-based methods.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

This study was conducted on two couples who underwent a PGT-M cycle at the Reproductive Medicine Center, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University. Patient 1 had a history of miscarriage in 2015 and was found to carry a duplication of DMD exons 15–17. The karyotypes of the couple were determined to be 46,XX, inv(9)(p12q13) for patient 1 and 46,XY for her husband. In the second pedigree, the couple had a son diagnosed with DMD. The karyotypes of this couple were identified to be 46,XX for patient 2 and 46,XY,1qh + for her husband. Blood samples were collected from the patients with complete informed consent. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (approval number: 2021012).

In vitro fertilization (IVF), blastocyst biopsy, and WGA

Metaphase II oocytes were fertilized by intracytoplasmic single-sperm injection, according to a standard protocol. Fertilized oocytes were then cultured for 5–6 days until they developed into blastocysts. Three to five trophectoderm cells were biopsied from fresh day-5/6 blastocysts and placed into PCR tubes. Subsequently, the cells were subjected to WGA using multiple annealing and looping-based amplification cycles (MALBAC). IVF, embryo culture, blastocyst biopsy, and cryopreservation were performed at the Reproductive Medicine Center, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, according to the previously published methods. In total, 5 embryos from pedigree 1 and 12 embryos from pedigree 2 were obtained and analyzed.

DNA extraction

Peripheral blood samples were collected from family members of both pedigrees for analysis. High-molecular-weight genomic DNA was extracted using the SDS method and purified using the QIAGEN® Genomic kit (Cat#13343, QIAGEN, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol24. DNA quality was assessed by monitoring degradation and contamination using 1% agarose gels. DNA purity was determined using a NanoDrop™ One UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA); OD260/280 ranged from 1.8 to 2.0 and OD 260/230 ranged from 2.0 to 2.2. Finally, the DNA concentration was measured using a Qubit® 3.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA).

Library preparation and nanopore sequencing

A total of 2 µg of DNA extracted from the peripheral blood of patients 1 and 2 was used as the input material for library preparation by Oxford Nanopore Technologies. The BluePippin system (Sage Science, USA) was used for qualified size selection of long DNA fragments. Subsequently, the ends of the DNA fragments were repaired and the A-ligation reaction was conducted using a NEBNext Ultra II End Repair/dA-tailing kit (Cat# E7546, NEB, USA). Further ligation was performed using the adapter in the LSK109 kit, and the size of the library fragments was quantified using a Qubit® 3.0 Fluorometer. Sequencing was performed using a PromethION 48 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK).

Data quality control

Nanopore sequencers output FAST5 files containing the signal data. These files were initially converted to the FASTQ format using Guppy. Raw reads in the FASTQ format with a mean_qscore_template of less than 7 were subsequently filtered to obtain pass reads.

SGS-based SNP genotyping

To simultaneously detect DMD mutations using haplotype linkage analysis and chromosomal abnormalities, PGT-M for DMD was performed using a targeted SGS assay. Briefly, trophectoderm biopsy samples were subjected to MALBAC-based WGA. A portion of the WGA products was sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 550 platform (Illumina, USA) to assess chromosomal copy number variations. The remaining WGA products were subjected to PCR using primers targeting single-nucleotide variants in the DMD gene. SNP information from all family members and embryos was then obtained via SGS on the same platform. Haplotype linkage analysis was conducted to select embryos that did not carry the maternal DMD mutation and had normal ploidy.

Validation of nanopore sequencing and SGS results

Following successful conception after PGT-M cycles, the patients were referred to the Department of Obstetrics at Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, for prenatal and postnatal follow-up. Nanopore sequencing and SGS-based results were confirmed through karyotype analysis and molecular diagnosis of amniotic fluid cells at 18–20 weeks of gestation.

Data availability

The data generated or analyzed in this study are available in the published article and its supplementary files. The sequence data have been deposited in the China National GeneBank DataBase (CNGBdb) with accession ID CNP0004795 (patient 1) and CNP0006038 (patient 2), respectively.

References

Verhaart, I. E. C. & Aartsma-Rus, A. Therapeutic developments for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 15, 373–386 (2019).

Sun, C., Shen, L., Zhang, Z. & Xie, X. Therapeutic strategies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an update. Genes (Basel). 11, 837 (2020).

Kolwicz, S. C. Jr. et al. Gene therapy rescues cardiac dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy mice by elevating cardiomyocyte Deoxy-Adenosine triphosphate. JACC Basic. Transl Sci. 4, 778–791 (2019).

Duan, D., Goemans, N., Takeda, S. & Mercuri, E. Aartsma-Rus, A. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 7, 13 (2021).

Fox, H., Millington, L., Mahabeer, I. & van Ruiten, H. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. BMJ 368, l7012 (2020).

Aartsma-Rus, A., Ginjaar, I. B. & Bushby, K. The importance of genetic diagnosis for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Med. Genet. 53, 145–151 (2016).

Koenig, M. et al. Complete cloning of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) cDNA and preliminary genomic organization of the DMD gene in normal and affected individuals. Cell 50, 509–517 (1987).

Chamberlain, J. R. & Chamberlain, J. S. Progress toward gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol. Ther. 25, 1125–1131 (2017).

Ren, Y. et al. Clinical application of an NGS-based method in the preimplantation genetic testing for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 38, 1979–1986 (2021).

Malcov, M. et al. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) by triplex-nested PCR. Prenat Diagn. 25, 1200–1205 (2005).

Ren, Z. et al. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis for Duchenne muscular dystrophy by multiple displacement amplification. Fertil. Steril. 91, 359–364 (2009).

Gui, B. et al. A new Next-Generation Sequencing-Based assay for concurrent preimplantation genetic diagnosis of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A and aneuploidy screening. J. Genet. Genomics. 43, 155–159 (2016).

Wu, H. et al. Long-read sequencing on the SMRT platform enables efficient haplotype linkage analysis in preimplantation genetic testing for β-thalassemia. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 39, 739–746 (2022).

Chow, J. F. C., Cheng, H. H. Y., Lau, E. Y. L., Yeung, W. S. B. & Ng, E. H. Y. Distinguishing between carrier and noncarrier embryos with the use of long-read sequencing in preimplantation genetic testing for reciprocal translocations. Genomics 112, 494–500 (2020).

Madjunkova, S. et al. Detection of structural rearrangements in embryos. N Engl. J. Med. 382, 2472–2474 (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. Long-read sequencing and haplotype linkage analysis enabled preimplantation genetic testing for patients carrying pathogenic inversions. J. Med. Genet. 56, 741–749 (2019).

Hu, L. et al. Location of balanced Chromosome-Translocation breakpoints by Long-Read sequencing on the Oxford nanopore platform. Front. Genet. 10, 1313 (2019).

Gao, M. et al. Noncarrier embryo selection and transfer in preimplantation genetic testing cycles for reciprocal translocation by Oxford nanopore technologies. J. Genet. Genomics. 47, 718–721 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Third-generation sequencing: any future opportunities for PGT? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 38, 357–364 (2021).

Xia, Q. et al. Nanopore sequencing for detecting reciprocal translocation carrier status in preimplantation genetic testing. BMC Genom. 24, 1 (2023).

Xia, Q. et al. Nanopore sequencing with T2T-CHM13 for accurate detection and preventing the transmission of structural rearrangements in highly repetitive heterochromatin regions in human embryos. Clin. Transl. Med. 14, e1612 (2024).

M, M. Y. et al. Variant haplophasing by long-read sequencing: a new approach to preimplantation genetic testing workups. Fertil. Steril. 116, 774–783 (2021).

Logsdon, G. A., Vollger, M. R. & Eichler, E. E. Long-read human genome sequencing and its applications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 597–614 (2020).

Boughattas, S. et al. Whole genome sequencing of marine organisms by Oxford nanopore technologies: assessment and optimization of HMW-DNA extraction protocols. Ecol. Evol. 11, 18505–18513 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study. We also thank the technicians at Yikon Genomics Co., Ltd. for their technical support.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (2023JJ30964 and 2024JJ6675).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Y.Y. conceived and supervised the study. T.L.C. and J.Q.L. collected the samples. Q.P.X. carried out the experiment and drafted the manuscript. Q.P.X. and T.L.D. analyzed the data. T.L.D. and Z.L. provided technical support. Y.P.L. and T.L.C. reviewed the manuscript. The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (approval number: 2021012). Complete informed consent for all procedures was obtained from the patients. Throughout the study, the collection and use of samples followed procedures that are in accordance with ethical standards as formulated in the Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, Q., Chang, T., Ding, T. et al. Clinical application of nanopore sequencing for haplotype linkage analysis in preimplantation genetic testing for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Sci Rep 15, 30498 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16358-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16358-x