Abstract

The Three-Dimensional Meaning in Life Scale (3DM) is a newly developed instrument designed to assess individuals’ meaning in life on the basis of an assumed trichotomous structure (i.e., significance, purpose, and coherence). The aim of this study was to translate the 11-item 3DM into Chinese and assess the psychometric characteristics of the Chinese version of the 3DM (3DM-C) among Chinese undergraduate students. In this cross-sectional study, two samples of undergraduate students were recruited using convenience sampling. Sample A consisted of 547 students, and the students filled out the 3DM-C, the Short Form 36 Health Survey Version 2, and the 9-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for Students and provided demographic information (e.g., gender, age, major, and annual household income). Sample B included 319 students, and the participants completed the 3DM-C, the Presence of Meaning subscale from the Meaning in Life Questionnaire, and the Flourishing Scale and provided the same demographic information as Sample A. For test‒retest analysis, 166 respondents from Sample A completed the 3DM-C again after two weeks. Confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated adequate structural fit with the three-factor (coherence, purpose, and significance) model and the hierarchical model based on a second-order latent factor that included the three first-order latent constructs of significance, purpose, and coherence (χ2 = 207.738, df = 41, CFI = 0.966, TLI = 0.954, RMSEA = 0.069). The standardized factor loadings for the second order factor are very high (ranged from 0.82 to 0.94). The 3DM-C’ total (Cronbach’s α = 0.91) and subscale (Cronbach’s α = 0.81–0.91) scores exhibited good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.81–0.84) and temporal stability (r = 0.69–0.80, intraclass correlation coefficients = 0.69–0.89), as well as strict invariance across genders (χ2 = 343.554, df = 109, CFI = 0.952, TLI = 0.952, RMSEA = 0.070, ΔCFI = -0.004). We found that the three factors of the 3DM-C play different roles in predicting psychological well-being, physical health, mental health, and academic engagement. These results further support the rationale for the uniqueness of the three dimensions of the 3DM-C. Overall, the 3DM-C demonstrated good psychometric properties within the Chinese cultural context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although meaning in life is a common part of daily experiences and has been extensively discussed by theologians, philosophers, and psychologists, its definition remains ambiguous. Meaning in life is a subjective experience or mental state1 that was first explored scientifically as a psychological concept by Viktor Frankl2. In recent years, researchers have made progress in achieving a well-recognized conception of meaning in life. Steger and colleagues defined it as the understanding and significance a person attributes to his or her existence3.

Researchers have sought to quantify this intuitive sense through self-report measures, such as the notable example of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) by Steger and colleagues3. The MLQ includes two dimensions: the search for meaning and the presence of meaning. Numerous studies have confirmed its association with various health outcomes, showcasing the higher global meaning, the greater reduction in mortality risk and incidence of physical disability4,5, the less severity of posttraumatic stress disorder6, and the lower probability of suicidal ideation7. The MLQ prompts respondents to rate their sense of meaning in life with direct questions (e.g., “I understand my life’s meaning”) without offering explicit definitions, which may raise concerns about its construct validity. Consequently, scholars have investigated the conceptualization of meaning in life and its components with more specific measurement methods8,9.

Researchers including King and Hicks1, Heintzelman and King8, Martela and Steger9, and George and Park10 concurred that meaning in life consists of three main components, comprehension or coherence, significance or mattering, and purpose, each of which contributes to a global sense of meaning10. Comprehension or coherence refers to individuals’ ability to understand their life and the world around them and reflects the cognitive aspect of meaning8,9. Purpose represents the feeling that one’s behavior is guided by goals or a central aim and helps to organize thoughts and actions11. Mattering or significance is the sense of one’s importance and the extent to which a person believes that his or her life counts1.

The concept of the trichotomous structure of meaning in life has been discussed in multiple studies12,13. Among the three dimensions, coherence and purpose are widely accepted by researchers; however, whether significance and mattering are the same construct remains debatable. To operationalize this trichotomy and empirically examine the independence of significance and mattering, Martela and Steger constructed the Three-Dimensional Meaning in Life Scale (3DM)14. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of the 3DM demonstrate that a highly correlated three-factor structure comprising significance, purpose, and coherence is appropriate for adult populations in the United States. The three dimensions of the 3DM independently predict constructs measured by the Presence of Meaning subscale of the MLQ and together account for 79% of the variance in the general experience of meaningfulness14. This suggests that the 3DM offers a comprehensive understanding of meaning in life. Additionally, the three dimensions of the 3DM demonstrate strong and positive correlations with positive affect, life satisfaction, competence, relatedness, and beneficence14. In summary, the 3DM, a new, brief, and comprehensive tool, has demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties and provides empirical evidence for the tripartite view of meaning in life.

Meaning in life might vary across cultures15, necessitating consideration of cultural differences when assessing it. Collectivist cultures such as China differ significantly from individualistic cultures (e.g., the USA) in various aspects. Culture can influence people’s experience of meaning in life by organizing experiences, imbuing life with purpose, and providing a sense of mattering1. In collectivist cultures, people are believed to have closer interpersonal relationships than they do in individualistic cultures. As functional meaning-making systems, worldviews, including religious faith, play a crucial role in shaping meaning in life16. For example, religiosity, which is a common reality in many cultures, is positively associated with meaning in life17. However, the association between nonreligious worldviews and sense of meaning remains underexplored. In China, most individuals, particularly Han Chinese, are identified as nonreligious. Because the 3DM was developed and validated within English-speaking contexts, its applicability to Chinese populations warrants further examination. Therefore, the aim of this research was to translate the original 3DM into Chinese and initially examine the factorial structure of the 3DM among a selected cohort of Chinese undergraduate students. We further validated the three-factor model of the Chinese version of the 3DM (3DM-C) based on first-order factor analyses and the hierarchical model of the 3DM-C based on a second-order latent factor that included the three first-order latent constructs of significance, purpose, and coherence.

Few studies have focused on the measurement invariance (MI) of the 3DM. Byrne and Watkins stated that MI is essential for comparing distinct groups because interpreting the variations in the mean across groups can be misleading and uncertain unless the underlying constructs of various subgroups are identical18. Thus, MI needs to be established to compare different groups, such as men and women. Previous research has shown that both women and men interpret the meaning of life on the basis of their unique gendered experiences and societal expectations19. Therefore, this research further investigated the MI of the 3DM across gender.

Furthermore, to address the scarcity of research that assesses the criterion-related validity of the 3DM, we explored the associations between meaning in life and its constituent dimensions with health-related quality of life (including both physical and mental aspects), psychological well-being and academic engagement. Extensive evidence highlights the intricate connection between meaning in life and health outcomes, indicating its pivotal role in enhancing health-related quality of life and psychological well-being14,15,20. Similarly, meaning in life fosters academic engagement because sentiments of significance, purpose, and coherence inspire a deeper appreciation for learning, motivate students to set academic goals, ignite curiosity, and amplify learning engagement21. To provide further validation of the 3DM, we conducted an analysis to assess its incremental validity. Specifically, we explored whether the total score or subscales of the 3DM could predict psychological well-being even after accounting for the presence of meaning captured by the subscale of the MLQ.

In summary, this study has the following objectives: (1) translate the 3DM into Chinese and test the three-factor structure of the 3DM-C among Chinese undergraduate students; (2) determine whether 3DM-C scores exhibit measurement invariance across genders; (3) assess the internal consistency and stability coefficients of the translated 3DM-C; and (4) to investigate the unique relationships between meaning in life and its dimensions with criterion-related variables, including the presence of meaning, health-related quality of life, psychological well-being, and academic engagement.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

Due to size of the instrument battery, we recruited two subsets of participants to lessen the burden on individual participant. Two samples of undergraduate students were recruited from Zunyi Medical University from May 8 to 26, 2024 using convenience sampling through Wenjuanxing, an online survey platform. Sample A consisted of 547 students, and Sample B included 319 students. The survey link was distributed via two Tencent QQ groups used for sharing campus life information, which comprised approximately 800 students (Sample A) and 650 students (Sample B). The participants were compensated with either 5 RMB or a public service certificate. The design of this study followed the guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zunyi Medical University (No. 2024-2-019). All participants indicated informed consent to participate in the research. Each participant could withdraw from the study at any stage of the project. Incomplete questionnaires were not allowed to be submitted in the survey platform Wenjuanxing.

In Sample A, the students completed the 3DM-C14, the Short Form 36 Health Survey Version 2 (SF-36 v2)22, and the 9-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for Students (UWES-9S)23 and provided demographic information (e.g., gender, age, major, and annual household income), from May 8 to 10, 2024. From May 11 to 12 (T1), the participants in Sample B completed the 3DM-C14, the Presence of Meaning subscale from the MLQ24, and the Flourishing Scale (FS)25 and provided the same demographic information as Sample A. For test‒retest analysis, 166 respondents from Sample B completed the 3DM-C again after two weeks, from May 25 to 26 (T2).

The participants in Sample A ranged from 17 to 24 years of age, with an average age of 19.5 ± 1.2 years. Women constituted 72.2% (N = 395) of the sample. In terms of ethnicity, 61.1% (N = 334) were Han Chinese, followed by Miao (9.3%), Buyi (6.4%), Tujia (6.0%), and other ethnic groups (collectively accounting for 17.2%). With respect to academic majors, 46.9% (N = 256) of the participants were studying clinical medicine, followed by dentistry (10.6%), medical imaging (8.6%), prevention medicine (7.3%), nursing (5.7%), and other majors (collectively accounting for 20.9%). Annual household income was measured by per capita annual income ranging from 1 (less than 5000 yuan) to 8 (more than 80000 yuan), and the mean annual household income was 2.08 ± 1.35.

Similarly, in Sample B, the age range was 17 to 24 years with a mean age of 19.3 ± 1.3 years. A total of 73.0% (N = 233) of the sample was women. Ethnically, 63.9% (N = 204) were Han Chinese, and the remaining participants were Tujia (7.2%), Miao (6.9%), Buyi (6.9%), and other ethnicities (collectively accounting for 15.0%). In terms of academic majors, 37.6% (N = 120) of the participants were studying clinical medicine, followed by prevention medicine (27.3%), dentistry (9.1%), nursing (5.3%), medical imaging (5.0%), and other majors (collectively accounting for 15.7%). Annual household income was also measured by per capita yearly income, with a scale from 1 (below 5000 yuan) to 8 (over 80000 yuan), and the mean annual household income was 2.29 ± 1.36.

Instruments

The three dimensional meaning in life scale (3DM)

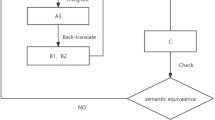

The 3DM is an 11-item scale with three subscales: significance (3 items, e.g., “My life is full of value”), purpose (4 items, e.g., “I pursue one or more big purposes in my life”), and coherence (4 items, e.g., “Most things happening in my life make sense”)14. The items are evaluated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). A greater mean score represents greater perceived meaning in life. The Chinese version (3DM-C) was developed using forward and back translations and reviewed by English language professors and senior psychologists to ensure equivalence with the original scale. The final Chinese version and the English back-translation version were reviewed by the two developers of the original scale (Martela and Steger). The English back-translation version and the original English version did not significantly differ. The items from the English version of the 3DM and the Chinese version (3DM-C) are listed in Table S1 of the online supplemental materials.

Presence of meaning subscale from the meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ)

The MLQ, which is a 10-item scale, was used to evaluate perceived meaning in life (Steger et al., 2006)3. This measure has two subscales: the search for meaning and the presence of meaning. The respondents rated each statement using a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating “not true at all” and 7 signifying “very true”. This research only used the presence of meaning subscale from the Chinese version of the MLQ24, which had a Cronbach’s α of 0.81 in sample B. The MLQ was adopted to assess the criterion and incremental validity of the 3DM-C.

The flourishing scale (FS)

The 8-item FS was used to assess positive state and mental health, with a 7-point Likert scale ranging 1 (not true at all) to 7 (very true)26. The Chinese version has good psychometric properties25, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.90 in sample B. The FS was used to assess the criterion and incremental validity of the 3DM-C.

The short form 36 health survey version 2 (SF-36 v2)

The SF-36 v2 is used to measure eight wellness domains that include general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional (constraints resulting from emotional health issues), mental health, physical functioning, role physical (constraints caused by physical health issues), and bodily pain22. These domains are divided into the mental component summary (MCS) and physical component summary (PCS). In sample A, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for PCS and MCS were 0.77 and 0.89, respectively. The SF-36 v2 was used to assess the criterion validity of the 3DM-C.

The 9-item Utrecht work engagement scale for students (UWES–9S)

The UWES-9S, which features 9 items, is used to assess academic engagement through three subscales: vigor (e.g., “When I’m doing my work as a student, I feel that I am bursting with energy”), dedication (e.g., “I am enthusiastic about my studies”), and absorption (e.g., “I feel happy when I am studying intensely”)27. Each item is evaluated on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always). We employed the Chinese version of the UWES–9S to create a composite academic engagement score23. In sample A, the Cronbach’s α for the overall scale was 0.90. The UWES–9S was adopted to assess the criterion validity of the 3DM-C.

Data analysis

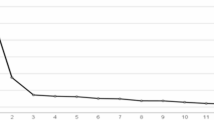

Factor Structure Analyses: To test the three-factor structure for the 3DM-C, we combined Sample A (N = 547) and Sample B (N = 319) to form an overall sample (N = 866). The result of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) showed that a three-factor structure of the 3DM-C could explain 58.4% of total variance. Given that the 3DM is built on a strong theoretical foundation, and we did not intend to refine the existing model, the EFA results of the 3DM-C are not presented. In line with a previous study14, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) with Mplus 8.328 to evaluate the one-factor model, the correlated three-factor model, and the hierarchical model, which is a second-order latent factor underpinned by the three first-order latent constructs of significance, purpose, and coherence. Considering the findings of a prior study and the skewness and kurtosis values (with a range from − 1.20 to + 1.66; see Table 1)14, we performed a series of CFAs using the maximum likelihood (ML) estimator. We assessed model fit with the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker‒Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI and TLI values greater than 0.95 and RMSEA values lower than 0.06 suggest a strong fit, whereas CFI and TLI values higher than 0.90 and RMSEA values lower than 0.08 reveal an adequate fit29,30. A model can be considered to have a better fit if the CFI and TLI values increase by a minimum of 0.01 or the RMSEA decreases by at least 0.01531.

MI: We conducted MI tests across genders following the procedure outlined by32: (a) configural invariance, (b) invariance of the factor loadings (metric invariance), (c) invariance of the thresholds (scalar invariance), and (d) invariance of the residual variances (strict invariance). Due to the influence of sample size on the chi-square difference test, we used changes (Δ) in the goodness-of-fit indices to assess invariance31. If the CFI of a model decreases by 0.01 or less compared to the previous model, the hypothesis of MI should be accepted31.

Internal Consistency and Test–Retest Reliability: We evaluated the internal consistency of the 3DM-C with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. According to Barker and colleagues33, alpha coefficient values ranging from 0.70 to 0.79 indicate adequate consistency, values from 0.80 to 0.89 suggest high consistency, and values exceeding 0.90 indicate excellent consistency. We calculated Pearson correlations and intraclass correlation coefficients to examine the test‒retest reliability of the 3DM-C. An intraclass correlation value between 0.60 and 0.74 indicates acceptable test‒retest reliability, whereas a coefficient of 0.75 or greater suggests high test‒retest reliability34.

Criterion Validity and Incremental Validity: For Sample A (N = 547), we report the zero-order correlations between the 3DM-C and various quality-of-life outcomes, specifically PCS and MCS, as well as academic engagement. The correlation coefficients were evaluated according to the criteria proposed by Cohen35, which categorize correlations as small if they are less than 0.30, moderate if they range from 0.30 to 0.50, and large if they exceed 0.50. Additionally, we conducted a variety of hierarchical regression analyses to evaluate the criterion validity of the total and subscale scores of the 3DM-C for PCS, MCS, and academic engagement, controlling for gender, age and annual household income. Similarly, in Sample B (N = 319), we reported the zero-order correlations between the 3DM-C and the presence of meaning and psychological well-being. Furthermore, we conducted a series of hierarchical regression analyses of Sample B (N = 319) to evaluate the incremental validity of the total and subscale scores of the 3DM-C for psychological well-being while controlling for the presence of meaning and demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age, and annual household income). To assess whether specific predictors had potentially significant contributions to (near) multicollinearity36,37, we used variance inflation factors (VIFs) and tolerance indices (TIs) as observational indices. VIFs greater than 10 indicate considerable multicollinearity36. TIs lower than 0.1 indicate presence of multicollinearity among predictors37.

Results

Factor structure and measurement invariance

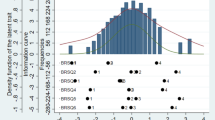

As shown in Table 2, the one-factor model revealed a poor fit to the data (CFI and TLI < 0.90, RMSEA > 0.08). In contrast, the correlated three-factor model and the hierarchical model, which are equivalent, revealed adequate fit indices (CFI and TLI > 0.95, RMSEA < 0.08). These models showed superior fit compared with the one-factor model (ΔCFI = 0.087 and ΔRMSEA = −0.055). The results of the three-factor model indicated that the factors (i.e., significance, purpose, and coherence) were highly correlated (r = 0.75–0.85). The standardized factor loadings for significance, purpose, and coherence factors in the hierarchical model ranged from 0.82 to 0.94. For each item within the three-factor model and the hierarchical model, they ranged from 0.54 to 0.88 (see Table 1).

The results for the invariance models for the correlated three-factor model across gender are shown in Table 2. The configural, metric, scalar, and all strict invariance models adequately fit the data (CFI and TLI > 0.95, RMSEA < 0.08), supporting strict invariance across gender (ΔCFI = −0.004).

Internal consistency and test-retest reliability

For the entire sample (N = 866), the overall Cronbach’s alpha for the 3DM-C was 0.91, indicating excellent internal consistency. The Cronbach’s alpha for the three dimensions (i.e., significance, purpose, and coherence) ranged from 0.81 to 0.84 (see Table 3), indicating high internal consistency. Additionally, the pairwise Pearson correlation values between T1 and T2 3DM-C total and subscale scores ranged from 0.69 to 0.80, and pairwise intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) between T1 and T2 3DM-C total and subscale scores ranged from 0.69 to 0.79 (see Table 3), suggesting good test-retest reliability.

Criterion validity and incremental validity

In line with our hypotheses, the 3DM-C total and subscale scores were positively associated with PCS (r > 0.25), MCS (r > 0.42), and academic engagement (r > 0.54) in Sample A (see Table 4). Hierarchical multiple regression analyses indicated that significance and coherence, but not purpose, significantly predicted PCS and MCS, respectively, without multicollinearity issues (VIFs < 2.36, TIs > 0.42). Furthermore, significance and purpose, but not coherence, significantly predicted academic engagement without multicollinearity issues (VIFs < 2.36, TIs > 0.42). The 3DM-C subscales accounted for 15.2%, 36.5%, and 46.6% of the variance in PCS, MCS, and academic engagement, respectively. The 3DM-C total score positively and significantly predicted PCS, MCS, and academic engagement without multicollinearity issues (VIFs < 1.03, TIs > 0.95), accounting for 12.7%, 33.1%, and 46.6% of the variance in PCS, MCS, and academic engagement, respectively. Corresponding results are available in Table S2 of the online supplementary materials.

Consistent with our assumptions, the 3DM-C total and subscale scores were positively associated with the presence of meaning (r > 0.60) and psychological well-being (r > 0.72) in Sample B (see Table 5). The results of hierarchical multiple regression analyses demonstrated that all 3DM-C subscale scores significantly predicted psychological well-being beyond the presence of meaning and demographic characteristics (i.e., gender and annual household income) in Sample B. The subscales explained 27.4% of the variance in psychological well-being with no multicollinearity issues (VIFs < 2.8, TIs > 0.35). Replacing the subscale scores with the total 3DM-C score significantly increased the explanatory power for psychological well-being by 24.6% without multicollinearity issues (VIFs < 2.3, TIs > 0.43). Corresponding results are available in Table S3 of the online supplementary materials.

Discussion

Our study initially investigated the psychometric properties of the 3DM-C in Chinese undergraduate students with different sociocultural backgrounds compared with the population for which it was originally devised and contributes new evidence on its suitability for Chinese culture. Overall, this 11-item scale showed sound psychometric properties, including structural validity, reliability, criterion validity and incremental validity.

With respect to structural validity, the results indicated that the correlated three-factor model demonstrated adequate fitness among Chinese undergraduate students. The factor structure of the 3DM-C aligns with the theoretical three-factor structures of significance, purpose, and coherence proposed by Martela and Steger14. More importantly, the hierarchical model, which are equivalent with the correlated three-factor model, demonstrated adequate fitness among Chinese undergraduate students. The standardized factor loadings for the second order factor are very high (ranged from 0.82 to 0.94), indicating that the hierarchical solution or second-order factor model is preferrable38,39. Our findings provide evidence for that significance, purpose, and coherence contributes to a global sense of meaning10, suggesting that the second order factor of meaning in life is meaningful to calculate the total score for lower-order factors (i.e., significance, purpose, and coherence). Our findings also revealed that this three-factor structure was strictly invariant across gender. Moreover, the 3DM-C revealed good internal consistency and temporal stability, which was absent in the original study by Martela and Steger14. Overall, these results suggest that the 3DM-C is an appropriate tool for comparing meaning in life across gender (i.e., males and females).

With respect to criterion validity, the 3DM-C and its three dimensions all show mid-level to high-level correlations with the presence of meaning (r ≥ 0.6), psychological well-being (0.72 < r < 0.86) and the MCS (0.42 < r < 0.58), in line with the findings of Martela and Steger14. Additionally, the 3DM-C and its dimensions exhibit low to moderate correlations with the PCS (0.25 < r < 0.39). These findings align with Park’s model40, which posits that meaning in life is a precursor to improved physical health, as well as with prior research that indicates that meaning in life positively predicts physical health20. Furthermore, it shows relatively high correlations with academic engagement (0.54 < r < 0.64), which supports previous findings that both meaning in life and positive meaning in academic study are positively linked to study engagement21,41. These findings provide new evidence of the positive link between meaning in life and various aspects, such as physical health and academic engagement, based on the trichotomy of meaning in life.

Moreover, in line with previous findings that the three dimensions of meaning in life (i.e., significance, coherence and purpose) predict well-being-related outcomes (i.e., positive affect, negative affect and life satisfaction)14, our results showed that both the 3DM-C and its three dimensions contributed to psychological well-being above and beyond the presence of meaning. These findings provide evidence for the incremental validity of meaning in life in contributing to psychological well-being after accounting for other constructs of meaning in life. Surprisingly, our results revealed that significance and coherence, rather than purpose, positively and significantly predicted the PCS and MCS scores measured by the SF-36, respectively. These findings differ from previous findings among U.S. participants14. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that a greater perception of purpose in life is strongly linked to reduced levels of depression and anxiety42. On the one hand, the reasons for these conflicting results may be attributed to the demographic composition of the sample or the adoption of varying tools for measuring outcomes. On the other hand, in contemporary times, Chinese people, particularly undergraduate students, differ from people in the West. Chinese people predominantly believe that life is short and fraught with suffering, fate is unpredictable, and the future is uncertain. The notion that “life is short” encourages a focus on living in the moment and appreciating the beauty of the present43. This perspective suggests that having a clear goal is not always necessary. Many adhere to the life philosophy that “whatever will be, will be,” implying that a less purposive approach to life can reduce anxiety, increase happiness, and ultimately improve quality of life44.

Our research distinctly contributes to the literature by revealing that significance and purpose, rather than coherence, positively and significantly predict academic engagement. This finding indicates that undergraduate students with greater degrees of significance and purpose are more inclined to engage in their studies. In contrast, a better understanding of one’s life does not necessarily correlate with increased academic engagement. Unlike middle school students, who primarily concentrate on the university entrance exam, undergraduate students, who have a broader understanding of their life and the world, tend to approach academic study in a more balanced manner45. They do not merely pursue higher grades, which may not be crucial for their career development. Instead, they may prioritize improving their comprehensive skills and employability46. Because research on the trichotomy of meaning in life is limited, more studies are needed to better understand the psychological and behavioral outcomes of significance, purpose and coherence.

Limitations and future directions

When interpreting these results, we should acknowledge a few limitations. First, the participants in our research were limited to a convenience sample from one university. Further research is warranted to replicate our results in more varied collectivist groups that include a wide range of ages and occupations as well as populations with different health issues. Second, although the measurement equivalence of the 3DM-C has been validated across male and female students, other populations, including different age groups, vocations or cultures, should be included to comprehensively reflect its measurement stability47. Third, we only used presence of meaning subscale of the MLQ in line with Martela and Steger’s study, future research should be further investigate the unique relationships between the 3DM-C’ total and subscale scores and search for meaning measured by MLQ. Fourth, as there are currently numerous multi-dimensional questionnaires for measuring various aspects of the sense of meaning in life, such as the Comprehensive Measure of Meaning (CMM) and the Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scale10,48, more empirical research is needed in the future to examine and contrast the cultural adaptability of these scales in the context of Chinese culture.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 3DM:

-

Three-Dimensional Meaning in Life Scale

- 3DM-C:

-

Chinese version of the Three-Dimensional Meaning in Life Scale

- MLQ:

-

Meaning in Life Questionnaire

- MI:

-

measurement invariance

- SF-36 v2:

-

Short Form 36 Health Survey Version 2

- PCS:

-

Physical component summary scores of the SF-36 v2

- MCS:

-

Mental component summary scores of the − 36 v2

- UWES-9s:

-

9-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for Students

- FS:

-

Flourishing Scale

- ML:

-

maximum likelihood

- CFI:

-

comparative fit index

- TLI:

-

Tucker‒Lewis index

- RMSEA:

-

root mean square error of approximation

- VIFs:

-

variance inflation factors

- TIs:

-

tolerance indices

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- M:

-

Mean

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- AE:

-

Academic engagement

- POM:

-

Presence of meaning

- PWB:

-

Psychological well-being

References

King, L. A. & Hicks, J. A. The science of meaning in life. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 72, 561–584. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-072420-122921 (2021).

Frankl, V. E. Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy 4th edn (Beacon Press, 1992).

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S. & Kaler, M. The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns. Psychol. 53 (1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80 (2006).

Boyle, P. A., Barnes, L. L., Buchman, A. S. & Bennett, D. A. Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosom. Med. 71 (5), 574–579. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a5a7c0 (2009).

Mota, N. P. et al. Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident physical disability in aging U.S. Military veterans. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 24 (9), 706–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2016.03.004 (2016).

Owens, G. P., Steger, M. F., Whitesell, A. A. & Herrera, C. J. Posttraumatic stress disorder, guilt, depression, and meaning in life among military veterans. J. Trauma. Stress. 22 (6), 654–657 (2009).

Corona, C. D., Van Orden, K. A., Wisco, B. E. & Pietrzak, R. H. Meaning in life moderates the association between morally injurious experiences and suicide ideation among U.S. Combat veterans: results from the National health and resilience in veterans study. Psychol. Trauma. 11 (6), 614–620. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000475 (2019).

Heintzelman, S. J. & King, L. A. On knowing more than we can tell: intuitive processes and the experience of meaning. J. Posit. Psychol. 8 (6), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.830758 (2013).

Martela, F. & Steger, M. F. The three meanings of meaning in life: distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. J. Posit. Psychol. 11 (5), 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623 (2016).

George, L. S. & Park, C. L. The multidimensional existential meaning scale: A tripartite approach to measuring meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. 12 (6), 613–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1209546 (2016).

McKnight, P. E. & Kashdan, T. B. Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-Being: an integrative, testable theory. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 13 (3), 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017152 (2009).

King, L. A., Heintzelman, S. J. & Ward, S. J. Beyond the search for meaning: A contemporary science of the experience of meaning in life. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 25 (4), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416656354 (2016).

Womick, J., Atherton, B. & King, L. A. Lives of significance (and purpose and coherence): subclinical narcissism, meaning in life, and subjective well-being. Heliyon 6 (5), e03982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03982 (2020).

Martela, F. & Steger, M. F. The role of significance relative to the other dimensions of meaning in life – an examination utilizing the three dimensional meaning in life scale (3DM). J. Posit. Psychol. 18 (4), 606–626. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2022.2070528 (2023).

Zhou, Z., Qi, W., He, Q., Wen, J. & Miao, M. Which one is the best for evaluating the multidimensional structure of meaning in life among chinese: A comparison of three multidimensional scales. Appl. Res. Qual. Life. 19, 1791–1810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-024-10307-y (2024).

Park, C. L. Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol. Bull. 136 (2), 257–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018301 (2010).

Dar, K. A. & Iqbal, N. Religious commitment and well-Being in college students: examining conditional indirect effects of meaning in life. J. Relig. Health. 58 (6), 2288–2297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0538-2 (2019).

Byrne, B. M. & Watkins, D. The issue of measurement invariance revisited. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 34 (2), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102250225 (2003).

Sumner, R. ; The shape of a life: Gender and its influence on purpose development. In A. L. Burrow & P. L. Hill (Eds.), The ecology of purposeful living across the lifespan: Developmental, educational, and social perspectives (pp. 149–164). Springer International Publishing. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52078-6_9

Czekierda, K. et al. Meaning in life and physical quality of life: Cross-lagged associations during inpatient rehabilitation. Rehabil Psychol. 64 (4), 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000281 (2019).

Huang, W. & Zhang, S. The impact of meaning in life on preservice teachers’ innovative behavior: the chain mediating effects of career calling and learning engagement. Curr. Psychol. 43 (20), 18294–18306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05671-9 (2024).

Zhou, K. et al. Psychometrics of the short form 36 health survey version 2 (SF-36v2) and the quality of life scale for drug addicts (QOL-DAv2.0) in Chinese Mainland patients with methadone maintenance treatment. PloS One. 8 (11), e79828. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079828 (2013).

Tang, H., Datu, J. A. D., Liu, Z., Shen, J. & Xing, Q. The engaged lives of encouraged students: academic encouragement, grit and academic engagement in Chinese first year undergraduate students. Curr. Psychol. 42 (23), 19526–19536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03057-3 (2022).

Liu, S. & Gan, Y. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the meaning in life questionnaire. Chin. Ment Health J. 24 (6), 478–482 (2010).

Duan, W. & Xie, D. Measuring adolescent flourishing: psychometric properties of flourishing scale in a sample of Chinese adolescents. J. Psychoeduc Assess. 37 (1), 131–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282916655504 (2019).

Diener, E. et al. New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 97 (2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y (2010).

Schaufeli, W. B., Martínez, I. M., Pinto, A. M., Salanova, M. & Bakker, A. B. Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 33 (5), 464–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005003 (2002).

Muthen, L. K. & Muthen, B. O. Mplus user’s guide. 8th ed. Muthen & Muthen. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2017.

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ Model. 6 (1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 (1999).

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T. & Grayson, D. Goodness of fit evaluation. In Contemporary Psychometrics (eds Maydeu-Olivares, A. & McArdle, J.) 275–340 (Erlbaum, 2005).

Cheung, G. W. & Rensvold, R. B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ Model. 9 (2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5 (2002).

Putnick, D. L. & Bornstein, M. H. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: the state of the Art and future directions for psychological research. Dev. Rev. 41, 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004 (2016).

Barker, C., Pistrang, N. & Elliot, R. Research Methods in Clinical and Counselling Psychology 3rd edn (Wiley, 1994).

Cicchetti, D. V. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol. Assess. 6 (4), 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284 (1994).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences 2nd edn (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Marcoulides, K. M. & Raykov, T. Evaluation of variance inflation factors in regression models using latent variable modeling methods. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 79 (5), 874–882. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164418817803 (2019).

Hongyun Liu. SPSS Basics and Application (China Renmin University, 2002).

Hou, J., Wen, Z. & Cheng, Z. Structural Equation Model and its Applications (Educational Science Publishing House, 2004).

Mengcheng Wang. Latent Variable Modeling Using Mplus (Publishing House of Chongqing University, 2014).

Park, C. L. Integrating positive psychology into health-related quality of life research. Qual. Life Res. 24, 1645–1651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0889-z (2015).

Kwok, S. Y. C. L. & Fang, S. A Cross-lagged panel study examining the reciprocal relationships between positive emotions, meaning, strengths use and study engagement in primary school students. J. Happiness Stud. 22 (3), 1033–1053. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00262-4 (2021).

Boreham, I. D. & Schutte, N. S. The relationship between purpose in life and depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. 79 (12), 2736–2767. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23576 (2023).

Killingsworth, M. A. & Gilbert, D. T. A wandering Mind is an unhappy Mind. Science 330 (6006). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1192439 (2010).

Sun, Z. Research on the Meaning of Life (Beijing Normal University Press (China), 2020).

Chankseliani, M., Qoraboyev, I. & Gimranova, D. Higher education contributing to local, national, and global development: new empirical and conceptual insights. High. Educ. 81 (1), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00565-8 (2021).

Dickinson, J., Griffiths, T. L. & Bredice, A. It’s just another thing to think about’: encouraging students’ engagement in extracurricular activities. J. Furth. High. Educ. 45 (6), 744–757. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1813263 (2020).

Schutte, L. et al. Measurement invariance of the meaning in life questionnaire across 17 countries. Appl. Res. Qual. Life. 18 (3), 1491–1519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10150-7 (2023).

Padgett, R. N. et al. Measuring meaning in life by combining philosophical and psychological distinctions: psychometric properties of the comprehensive measure of meaning. J. Posit. Psychol. 20 (4), 682–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2024.2403367 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to all the participants for their assistance in the study and Dr. Jiahong Zhang for their review of the initial Chinese version of the Three Dimensional Meaning in Life Scale.

Funding

We are grateful for being supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Bases at the Colleges and Universities of Guizhou Provincial Department of Education (Granted No: 23GZGXRWJD2131), High-level Project Cultivation Program Funded Project of Zhaoqing University (Granted No: GCCSK202402), and Fourth Batch of Innovative Research Teams of Zhaoqing University (Granted No: TD202403).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhijun Liu and Hui Tang conceptualized and designed the project, performed the statistical analyses, and wrote and revised the manuscript; Nian Tian, Qiaoyu Guo, Yu Dai collected the data, reviewed, and revised the manuscript; Chaojie Liu provided scientific support and professional guidance, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All the authors proofread and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The design of this study followed the guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by Ethics Committee of Zunyi Medical University (No. 2024-2-019). The authors obtained informed consent from all undergraduate students to participate in the research. Each participant could withdraw from the study at any stage of the project.

Consent for publication

Included in the informed consent provided by all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Tian, N., Guo, Q. et al. Psychometric properties of the Three-Dimensional Meaning in Life Scale in Chinese undergraduate students. Sci Rep 15, 30995 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16656-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16656-4