Abstract

To explore the associations between temperature trajectories and in-hospital mortality and renal replacement therapy in patients with sepsis-associated acute kidney injury (SA-AKI). By using data from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC)-IV, participants were divided into three groups (≤ 36 °C, 36–38 °C, ≥ 38 °C). We identified body temperature trajectories by a latent class mixed model and explored the associations of these trajectories with in-hospital mortality using Cox hazard proportional regression models, further exploring the associations with renal replacement therapy using logistic regression models. Total 1,831 in-hospital deaths during 9,760 person-years of follow-up were documented. In the hypothermia group, five different temperature trajectory classes were identified: L1, L2, L3, L4, and L5. Similarly, four trajectory classes (M1, M2, M3, and M4) emerged in the normal temperature group, whereas the hyperthermia group presented four distinct trajectory classes (H1, H2, H3, and H4). Compared with patients with the M3 trajectory, those with the L1 (hazard ratio [HR]: 2.41, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.58–3.66), L2 (HR: 1.48, 95% CI 1.11–1.97), L3 (HR: 1.27, 95% CI 1.01–1.59), L4 (HR: 1.29, 95% CI 1.08–1.54), and M1 (HR: 1.29, 95% CI 1.06–1.57) trajectories were at greater risk of in-hospital mortality. For patients with different baseline temperatures, the L1 (HR: 1.95, 95% CI 1.19–3.18), M1 (HR: 1.28, 95% CI 1.05–1.56), and H4 (HR: 2.37, 95% CI 1.05–5.36) trajectories were related to an elevated risk of in-hospital mortality. The study suggests that early body temperature trajectories are linked to increased in-hospital mortality risk in patients with SA-AKI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury (SA-AKI) is a severe and life-threatening complication in critically ill patients that significantly contributes to morbidity and mortality1,2. This multifactorial condition is characterized by a rapid decline in kidney function, often accompanied by systemic inflammation, organ dysfunction, and poor outcomes3,4. Between 41% and 62.3% of sepsis patients in intensive care units (ICUs) develop AKI, with the rate of mortality in patients with SA-AKI exceeding 50%5,6,7,8. Furthermore, the presence of both AKI and sepsis notably elevates the risk of ICU and in-hospital mortality9. Compared with patients with nonseptic AKI, patients with SA-AKI in the ICU are at greater risk for severe illness, increased mortality, and increased dialysis requirements9. Therefore, early identification of SA-AKI is vital for preventing complications, reducing mortality, and improving clinical outcomes.

The kidneys play a crucial role in thermoregulation, and their dysfunction may directly affect the ability to regulate body temperature. Studies have shown that the integrated response of the kidneys under heat stress contributes to thermoregulation, cardiovascular control, and the regulation of water and electrolytes10. However, the risk of pathological events in the kidneys increases during heat stress, especially in cases of dehydration and exercise, which may lead to AKI and potentially progress to chronic kidney disease (CKD). This risk is particularly significant in older adults due to changes in renal structure and physiological function that may make them more susceptible to injury during heat stress. Furthermore, hospitalization rates during fever are significantly higher in patients with chronic kidney disease, closely related to renal dysfunction under heat stress. Research indicates that during fever, water and electrolyte imbalance and acute kidney injury are the primary reasons for hospitalization in older adults11. Under conditions of heat stress, renal dysfunction can lead to a decline in the ability to regulate body temperature. Studies show that the response of the kidneys to heat stress involves not only thermoregulation but also cardiovascular and water-electrolyte regulation12. Renal dysfunction can disrupt these regulatory mechanisms, affecting the stability of body temperature. Therefore, maintaining renal function is crucial for normal thermoregulation, especially when facing extreme environmental conditions.

The pathophysiology of SA-AKI is complex and involves a combination of hemodynamic instability, inflammatory mediators, and renal tubular damage13,14. Emerging evidence suggests that body temperature may serve as a potential indicator of clinical severity and disease progression4,15,16,17,18. Early temperature abnormalities may reflect a dysregulated response to infection; fever is often observed as part of the body’s inflammatory cascade and associated with lower mortality in sepsis patients16,19. In contrast, hypothermia is commonly linked to a higher incidence of AKI20. The dynamic fluctuations in body temperature may represent a heterogeneous immune response in patients with sepsis. Several temperature trajectory phenotypes have been identified in sepsis, with varying immune profiles across these phenotypes. Patients with persistently low temperatures have the highest mortality rates, whereas those with initially elevated temperatures followed by rapidly decreasing temperatures have relatively low mortality rates21,22. Prognostic models indicate that a higher baseline body temperature is also associated with reduced mortality in ICU patients with SA-AKI23,24. Hypothermia has been reported to enhance renal function, potentially preventing or minimizing injury and assisting in renal recovery by reducing metabolic demand, decreasing free radical production, promoting cellular integrity, limiting apoptosis, and exerting anti-inflammatory effects25,26. In renal ischemia‒reperfusion injury models, sustained hypothermia has been shown to mitigate renal damage27.

The precise relationship between early temperature trajectories and clinical outcomes in patients with SA-AKI remains adequately defined. This study aimed to address this gap by exploring these associations, thereby contributing to the refinement of prognostic models and development of targeted interventions for patients with SA-AKI.

Methods

Study participants

The present retrospective study utilized the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC)-IV-ICU-v2.0 database, which includes ICU admission data from critically ill patients at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) collected between 2008 and 2022. The deidentified data, which were collected during routine clinical care, were processed and made available to qualified researchers who completed the necessary human research ethics training and signed a data use agreement. The Institutional Review Board at BIDMC waived the requirement for informed consent and authorized the sharing of research resources. All the data can be accessed publicly at https://mimic.mit.edu/docs/iv/.

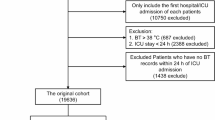

Patients diagnosed with SA-AKI upon their first ICU admission were included in the analysis. Sepsis was identified on the basis of the Sepsis-3 criteria, where patients with a documented or suspected infection and a ≥ 2-point increase in the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score are classified as septic1. Acute kidney injury was diagnosed according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines, defined as an increase of 0.3 mg/dl in the serum creatinine (Scr) level within 48 h, a 1.5-fold increase in the Scr level from baseline within the previous 7 days, or a urine output < 0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 h28. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) an age < 18 years, (2) an ICU stay < 24 h, (3) missing creatinine data, (4) a history of kidney transplant, (5) the presence of end-stage renal disease at ICU admission, (6) the use of renal replacement therapy (RRT) within 24 h of ICU admission, (7) a lack of AKI assessment during follow-up, (8) fewer than three temperature measurements within 24 h of ICU admission, and (9) missing survival information. The detailed selection process is depicted in Fig. 1.

Measurement of body temperature

Body temperature was measured within the first 24 h of ICU admission. According to many scoring systems (e.g., APACHE II, PIRO, SAPS II, SIRS), body temperature below 36.0 °C or above 38.0 °C are considered equally pathological1, which values are in accordance with the criteria of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. In present study, patients were categorized into three groups on the basis of their maximum body temperature during the first 24 h: the hypothermia group (< 36 °C), the normal temperature group (36–38 °C), and the hyperthermia group (> 38 °C)19. Body temperature trajectories were determined using a latent class mixed model (LCMM), which analyzes individual developmental patterns from repeated longitudinal measurements and defines population heterogeneity as a finite number of latent classes29. Individuals with similar trajectories are assigned to the same latent class on the basis of the calculated probabilities. These latent classes represent distinct trajectory groups.

Outcomes and follow-up

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality, whereas the secondary outcome was the receipt of RRT from 24 h after ICU admission to ICU discharge. Follow-up was conducted from admission to the ICU until discharge or death.

Data collection

Structured Query Language (SQL) was used to extract data recorded on the first day of ICU admission. The extracted data included sociodemographic data, vital signs data, first care unit data, laboratory data, pretreatment scoring system data, and data on drugs used during the ICU stay. Sociodemographic data included age, sex, race, insurance status, marital status, and weight. Vital signs data included data on temperature, heart rate, mean arterial pressure (MAP), and respiratory rate. For patients, the first care unit data (Medical Intensive Care Unit [MICU], Surgical Intensive Care Unit [SICU], Cardiac Vascular Intensive Care Unit [CVICU], and others) were also documented. The laboratory data included the white blood cell (WBC) count, platelet count, red blood cell (RBC) count, hemoglobin level, hematocrit level, red cell distribution width (RDW), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), international normalized ratio (INR), prothrombin time (PT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level, glucose level, lactate level, anion gap, and calcium level. The pretreatment scoring systems included the SOFA score and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). Drugs used during the ICU stay, including antibiotics, vasopressors, ibuprofen, aspirin, acetaminophen, and diuretics, were also recorded. Additionally, SpO2, AKI severity, 24-hour urine output, RRT use, and first-day ventilation use were included.

Statistical analysis

An LCMM was employed to identify subgroups of patients with SA-AKI exhibiting similar longitudinal temperature trajectories. LCMMs divide heterogeneous populations by estimating latent classes and model individual trajectories using linear mixed models30,31. This model calculated the probability of each individual’s longitudinal body temperature trend belonging to each potential class, assigning the class with the highest probability. Separate models for Groups 1–3 were fitted in each functional form, with optimal models selected on the basis of the following criteria: (1) the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC); (2) an entropy value > 0.7; (3) group membership > 1% for each class; (4) a posteriori probability > 0.7 for each class; and (5) the clinical significance of the classification.

The normality of continuous data was detected using skewness and kurtosis, whereas homogeneity was detected by the Levene test. Continuous data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs) for normally distributed data and as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for nonnormally distributed data. Categorical data are reported as numbers and percentages (%). For continuous data, Student’s t tests, Satterthwaite t tests, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were performed to evaluate the differences between two groups. Chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical data comparisons. Missing data were addressed through multiple imputations, followed by a sensitivity analysis before and after imputation. Covariates with a P value < 0.05 in the univariate Cox and logistic regression models were identified as potential confounders. Both univariate and multivariate Cox and logistic regression models incorporating bidirectional stepwise regression were used to examine the relationships between temperature trajectories and in-hospital mortality and RRT use in patients with SA-AKI. Hazard ratios (HRs), odds ratios (ORs), and confidence intervals (CIs) were computed to assess these relationships. Latent class analysis was performed using the R package ‘lcmm’ in R V.4.3.1, with additional analyses also conducted via R software. A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Characteristics of patients with SA-AKI

Among the 9760 individuals included, the median age was 66.79 years (IQR: 51.29–82.29 years), with 5639 (57.78%) male participants. During the 8.25-day (IQR: 3.10-22.98 days) follow-up, 1831 (18.76%) individuals died in the hospital, and 521 (5.34%) participants received RRT during their ICU stay. The mean body temperature was 36.65 (0.94)°C. Compared with patients with SA-AKI without in-hospital mortality, those with in-hospital mortality were more likely to be older, have Medicare insurance, have more severe AKI, use vasopressors, and use RRT. Compared with patients with SA-AKI without in-hospital mortality, those with in-hospital mortality had higher SOFA scores, CCIs, heart rates, WBC counts, and BUN levels and lower 24-hour urine output, SPO2 levels, and eGFRs (all P < 0.05). Table 1 shows more detailed characteristics of the patients with SA-AKI. No significant differences were observed before and after the imputation of data for the missing variables (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Body temperature trajectories of patients with SA-AKI in the first 24 h after ICU admission

We selected models with latent classes contained in the hypothermia, normal temperature, and hyperthermia groups on the basis of the lowest AIC and BIC values and an entropy value > 0.7. Additionally, the model had mean posterior class membership probabilities ranging between 0.7 and 0.81 and the highest relative entropy among the models with different classes, suggesting that this model provided better discrimination. The estimation of the models for a varying number of latent classes is summarized in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4. The different body temperature trajectories of each class are depicted in Fig. 2. In the hypothermia group, five different temperature trajectory classes were identified: L1, L2, L3, L4, and L5. Similarly, four trajectory classes (M1, M2, M3, and M4) emerged in the normal temperature group, whereas the hyperthermia group presented four distinct trajectory classes (H1, H2, H3, and H4). Each trajectory class represented unique patterns of temperature variations within the first 24 h of ICU admission. The overall distribution of trajectory classes varied, with some patients showing rapid temperature increases and others showing gradual decreases or maintaining relatively stable temperature levels.

Associations between body temperature trajectories and in-hospital mortality

Covariates, including RRT use, age, insurance status, marital status, first care unit, AKI severity, 24-hour urine output, SOFA score, CCI, weight, heart rate, respiratory rate, SPO2 level, RBC count, hematocrit level, RDW, eGFR, PT, BUN level, lactate level, anion gap, ibuprofen use, aspirin use, and acetaminophen use (Supplementary Table S5), were adjusted for. Compared with patients with the M3 trajectory, those with the L1 (HR: 2.41, 95% CI 1.58–3.66), L2 (HR: 1.48, 95% CI 1.11–1.97), L3 (HR: 1.27, 95% CI 1.01–1.59), L4 (HR: 1.29, 95% CI 1.08–1.54), and M1 (HR: 1.29, 95% CI 1.06–1.57) trajectories were at greater risk of in-hospital mortality. Compared with patients with a body temperature between 36 °C and 38 °C, those with a temperature < 36 °C (HR: 1.29, 95% CI 1.13–1.47) had an increased risk of in-hospital mortality (Table 2). This association was further analyzed in patients with SA-AKI with varying baseline temperatures. In the hypothermia group, the L1 (HR: 1.95, 95% CI 1.19–3.18) trajectory was associated with increased in-hospital mortality risk. In the normal temperature group, the M1 (HR: 1.28, 95% CI 1.05–1.56) trajectory was related to elevated in-hospital mortality risk. In the hyperthermia group, the H4 (HR: 2.37, 95% CI 1.05–5.36) trajectory was associated with increased in-hospital mortality risk (Table 3).

Associations between body temperature trajectories and RRT use

Additionally, we examined the links between body temperature trajectories and RRT use. Covariates, including age, marital status, 24-hour urine output, SOFA score, respiratory rate, eGFR, glucose, antibiotics, ventilation, vasopressors, diuretics, ibuprofen use, aspirin use, and acetaminophen use, were adjusted for (Supplementary Table S6). Among all patients with SA-AKI, the M2 (HR: 1.32, 95% CI 1.01–1.73), M4 (HR: 1.65, 95% CI 1.03–2.66), H1 (HR: 4.96, 95% CI 1.38–17.77), and H4 (HR: 6.52, 95% CI 1.74–24.42) trajectories were linked to increased odds of receiving RRT (Table 4). In the normal temperature group, the M4 (HR: 1.66, 95% CI 1.03–2.68) trajectory was associated with increased odds of receiving RRT. For the hyperthermia group, the H1 (HR: 5.19, 95% CI 1.04–25.75) and H4 (HR: 5.45, 95% CI 1.03–28.76) trajectories were correlated with a higher incidence of RRT use (Table 5).

Discussion

We found that in patients with SA-AKI, a gradual increase in the hypothermia trajectory (L1), a decrease followed by an increase in the normal trajectory (M1) and an increase followed by a gradual decrease in the hyperthermia trajectory (H4) were both associated with an increased in-hospital mortality risk compared with a stable normal temperature trajectory (M3). With respect to RRT use, the M4, H1, and H4 trajectories, characterized by substantial fluctuations in body temperature, were significantly associated with a higher incidence of RRT use. Our findings agree with those of previous studies that have suggested a link between body temperature abnormalities and adverse outcomes in patients with sepsis.

Our findings align with and build upon previous studies investigating the relationship between body temperature fluctuations and outcomes in patients with sepsis. Research has indicated that both fever and hypothermia can contribute to poor prognosis in sepsis patients, as they are markers of systemic inflammation and underlying physiological dysfunction32. Bhavani SV et al.22 found that hypothermic patients, who had the highest mortality rate, also presented the lowest levels of most pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Similar findings were also reported by Zhao et al.16, Yang et al.17, and Doman et al.18. Han et al.33 reported that in hypothermic sepsis patients, an increase of 1 °C or more in body temperature after the initial 6 h was associated with a reduced risk of 28-day mortality, which is similar to our findings. Unlike previous studies that focused primarily on peak or nadir temperature values, our findings underscore the importance of monitoring temperature trends, particularly in the early stage of SA-AKI, to predict patient prognosis more accurately.

The mechanisms underlying the observed associations between temperature trajectories and clinical outcomes in patients with SA-AKI are likely multifactorial and reflect underlying pathophysiological processes in sepsis. Body temperature-related markers, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α levels, is increased in response to infection and inflammation4,34,35. Our study indicates that both gradual increases in hypothermic temperature trajectories and fluctuations within the normal range are associated with poorer outcomes, likely due to disrupted thermoregulation and systemic inflammation.

The gradual increase in the hypothermic trajectory (L1) observed in our study may reflect a progressive collapse of the thermoregulatory and immune systems, potentially due to a systemic inflammatory response or inadequate compensatory mechanisms in the context of SA-AKI. In sepsis, hypothermia is often associated with impaired peripheral vasoconstriction and reduced metabolic activity, both of which can contribute to poor organ perfusion and worsening kidney function33,36. The increase in temperature following a decrease in the normal trajectory (M1) could signify a dysregulated immune response or an inadequate compensatory mechanism in response to infection, possibly leading to endothelial dysfunction and increased risk for organ failure. Temperature fluctuations, particularly rapid increases or decreases in body temperature, suggest a disturbed immune response and metabolic disturbance, both of which contribute to increased mortality risk in patients with SA-AKI37,38. An increase followed by a gradual decrease in the hyperthermia trajectory (H4) showed body temperature trajectory remained above 38 °C for an extended period, indicating persistent high inflammation or hyperdynamic state post-admission. Studies have shown that high temperatures can directly damage renal tubules39,40, and excessive inflammatory responses can further exacerbate renal ischemia and hypoxia, leading to AKI39. Although some believe that fever-induced renal function decline may be a self-protective mechanism to reduce water loss10, sustained elevation in body temperature still negatively impacts renal function more than positively. In contrast, a stable normal temperature trajectory appears to reflect better immune regulation and organ function, as patients with stable temperatures are less likely to experience drastic alterations in clinical status.

Our findings provide new insights into the utility of temperature monitoring in patients with SA-AKI. Current management strategies for septic patients often focus on addressing the underlying infection and supporting organ function, with temperature monitoring being a routine part of patient assessment. However, our study suggests that early, dynamic changes in temperature, rather than just static temperature measurements, can be critical for identifying patients at high risk for in-hospital mortality and those who need RRT. By integrating temperature trajectory monitoring into routine clinical practice, health care providers may be able to identify high-risk patients earlier, allowing timely interventions to mitigate further organ damage and improve outcomes. Moreover, these findings suggest that interventions aimed at stabilizing body temperature, such as targeted temperature management, might hold promise for improving the prognosis of SA-AKI, although further research is needed to assess the effectiveness of such approaches in this specific cohort.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, our study was observational, and while our findings were statistically significant, we cannot draw definitive causal conclusions. The observed associations between temperature trajectories and outcomes may be influenced by unmeasured confounding variables (such as antipyretics or ECMO), which could affect both body temperature and clinical outcomes. Additionally, recent researches indicate that the prognostic significance of temperature patterns may vary significantly across different ICU subgroups41,42, our findings are based on a specific cohort of patients with SA-AKI, which limits the generalizability of the results to other patient populations or those with different underlying conditions. Further studies examining a broader range of patients and conditions are needed to determine whether body temperature trajectories can serve as universal prognostic markers for other forms of acute kidney injury or sepsis.

In summary, our study suggested that early body temperature trajectories, including a gradual increase in the hypothermia trajectory, a decrease followed by an increase in the normal trajectory and an increase followed by a gradual decrease in the hyperthermia trajectory, were both associated with increased in-hospital mortality risk in patients with SA-AKI. Large fluctuations in temperature, particularly in the normal temperature and hyperthermia trajectories, were associated with the receipt of RRT. These findings highlight the potential role of body temperature trajectories as early indicators of clinical deterioration and emphasize the importance of early monitoring and intervention for patients with SA-AKI. However, further research is needed to validate these associations and explore the underlying mechanisms by which temperature dysregulation influences clinical outcomes in patients with SA-AKI.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the MIMIC-Ⅳ.

References

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). Jama 315 (8), 801–810 (2016).

Markwart, R. et al. Epidemiology and burden of sepsis acquired in hospitals and intensive care units: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 46 (8), 1536–1551 (2020).

White, K. C. et al. Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit: Incidence, patient characteristics, timing, trajectory, treatment, and associated outcomes. A multicenter, observational study. Intensive Care Med. 49 (9), 1079–1089 (2023).

Pais, T., Jorge, S. & Lopes, J. A. Acute kidney injury in sepsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (11), 5924 (2024).

Donaldson, L. H. et al. Quantifying the impact of alternative definitions of Sepsis-Associated acute kidney injury on its incidence and outcomes: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care Med. 52 (8), 1264–1274 (2024).

Song, M. J. et al. Epidemiology of sepsis-associated acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: A multicenter, prospective, observational cohort study in South Korea. Crit. Care. 28 (1), 383 (2024).

Fang, Y. et al. Association between renal mean perfusion pressure and prognosis in patients with sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: insights from the MIMIC IV database. Ren. Fail. 47 (1), 2449579 (2025).

Li, H. et al. Trends and outcomes in sepsis hospitalizations with and without acute kidney injury: A nationwide inpatient analysis. Shock 62 (4), 470–479 (2024).

Gao, N. et al. [A multicenter clinical study of critically ill patients with sepsis complicated with acute kidney injury in beijing: Incidence, clinical characteristics and outcomes]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 36 (6), 567–573 (2024).

Chapman, C. L. et al. Kidney physiology and pathophysiology during heat stress and the modification by exercise, dehydration, heat acclimation and aging. Temp. (Austin). 8 (2), 108–159 (2021).

Layton, J. B. et al. Heatwaves, medications, and heat-related hospitalization in older medicare beneficiaries with chronic conditions. PLoS One. 15 (12), e0243665 (2020).

Kwiatkowski, M. J. et al. [Water-sodium homeostasis in hemodialysis - the eternal problem in nephrology practice]. Pol. Merkur Lekarski. 49 (292), 311–315 (2021).

Yamada, S. et al. Phosphate overload directly induces systemic inflammation and malnutrition as well as vascular calcification in uremia. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 306 (12), F1418–F1428 (2014).

Fang, L. et al. Systemic inflammatory response following acute myocardial infarction. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 12 (3), 305–312 (2015).

Kuwabara, S., Goggins, E. & Okusa, M. D. The pathophysiology of Sepsis-Associated AKI. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17 (7), 1050–1069 (2022).

Zhao, Y. & Zhang, B. Association between body temperature and all-cause mortality in patients with sepsis: analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Eur. J. Med. Res. 29 (1), 630 (2024).

Yang, W. et al. The Association between Body Temperature and 28-day Mortality in Sepsis Patients: A Retrospective Observational Study (Med Intensiva (Engl Ed), 2024).

Doman, M. et al. Temperature control in sepsis. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 10, 1292468 (2023).

Rumbus, Z. et al. Fever is associated with reduced, hypothermia with increased mortality in septic patients: A Meta-Analysis of clinical trials. PLoS One. 12 (1), e0170152 (2017).

Wiewel, M. A. et al. Risk factors, host response and outcome of hypothermic sepsis. Crit. Care. 20 (1), 328 (2016).

Bhavani, S. V. et al. Identifying novel sepsis subphenotypes using temperature trajectories. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 200 (3), 327–335 (2019).

Bhavani, S. V. et al. Distinct immune profiles and clinical outcomes in sepsis subphenotypes based on temperature trajectories. Intensive Care Med. 50 (12), 2094–2104 (2024).

Fan, Z. et al. Construction and validation of prognostic models in critically ill patients with sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: interpretable machine learning approach. J. Transl Med. 21 (1), 406 (2023).

Gao, T. et al. Machine learning-based prediction of in-hospital mortality for critically ill patients with sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Ren. Fail. 46 (1), 2316267 (2024).

Moore, E. M. et al. Therapeutic hypothermia: benefits, mechanisms and potential clinical applications in neurological, cardiac and kidney injury. Injury 42 (9), 843–854 (2011).

Polderman, K. H. Mechanisms of action, physiological effects, and complications of hypothermia. Crit. Care Med. 37 (7 Suppl), S186–202 (2009).

Delbridge, M. S. et al. The effect of body temperature in a rat model of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transpl. Proc. 39 (10), 2983–2985 (2007).

Wang, B. et al. The neutrophil Percentage-to-Albumin ratio is associated with All-Cause mortality in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, p5687672 (2020).

Proust-Lima, C., Philipps, V. & Liquet, B. Estimation of extended mixed models using latent classes and latent processes: the R package Lcmm. J. Stat. Softw. 78 (2), 1–56 (2017).

Li, C. et al. Trajectories of perioperative serum tumor markers and colorectal cancer outcomes: A retrospective, multicenter longitudinal cohort study. EBioMedicine 74, 103706 (2021).

Burro, R. et al. An Estimation of a nonlinear dynamic process using latent class extended mixed models: Affect profiles after terrorist attacks. Nonlinear Dynamics Psychol. Life Sci. 22 (1), 35–52 (2018).

Thomas-Rüddel, D. O. et al. Fever and hypothermia represent two populations of sepsis patients and are associated with outside temperature. Crit. Care. 25 (1), 368 (2021).

Han, D. et al. Temperature trajectories and mortality in hypothermic sepsis patients. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 84, 18–24 (2024).

Drewry, A. & Mohr, N. M. Temperature management in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 50 (7), 1138–1147 (2022).

Guzelj, D. et al. The effect of body temperature changes on the course of treatment in patients with pneumonia and sepsis: Results of an observational study. Interact. J. Med. Res. 13, e52590 (2024).

Hariri, G. et al. Narrative review: clinical assessment of peripheral tissue perfusion in septic shock. Ann. Intensiv. Care. 9 (1), 37 (2019).

Cao, M., Wang, G. & Xie, J. Immune dysregulation in sepsis: Experiences, lessons and perspectives. Cell. Death Discov. 9 (1), 465 (2023).

van der Poll, T., Shankar-Hari, M. & Wiersinga, W. J. The immunology of sepsis. Immunity 54 (11), 2450–2464 (2021).

Amorim, F. & Schlader, Z. The kidney under heat stress: A vulnerable state. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 34 (2), 170–176 (2025).

Sato, Y. et al. Increase of core temperature affected the progression of kidney injury by repeated heat stress exposure. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 317 (5), F1111–F1121 (2019).

Jie Yang, B. Z. et al. Identification of clinical subphenotypes of sepsis after laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic, Endoscopic and Robotic Surgery, Volume 7(Issue 1): p. Pages 16–26. (2024).

Jie Yang, L. W. et al. A comprehensive step-by-step approach for the implementation of target trial emulation: Evaluating fluid resuscitation strategies in post-laparoscopic septic shock as an example. Laparoscopic, Endoscopic and Robotic Surgery, Volume 8(Issue 1): pp. 28–44. (2025).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-Ⅳ) for the offering the related data regarding the paper. Patients or the public WERE NOT involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.F. and M.Z. designed this study. N.F., Z.S.,T.G. and L.G. analyzed data. Z.S. and N.F. wrote the paper. N.F. and M.Z. revised the manuscript. Z.S., T. G. and L. G. contributed equally as first author in this work.All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, Z., Gao, T., Gao, L. et al. Early body temperature trajectories and short term prognosis in sepsis associated acute kidney injury. Sci Rep 15, 31820 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17170-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17170-3