Abstract

Understanding the factors contributing to neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) in older adults with mild behavioral impairment (MBI) is crucial for developing effective interventions. Although psychological resilience and social support are key factors related to NPS, with anxiety and sleep quality playing significant roles, the precise mechanisms underlying their relationships remain unclear. Therefore, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of 328 older adults with MBI in 42 nursing homes across nine cities in Fujian Province, Southeast China, and investigated how psychological resilience, sleep quality, and anxiety influence the relationship between social support and NPS in older adults with MBI. Our findings showed that social support was significantly linked to NPS (β = -0.194, p < 0.001); psychological resilience mediated the relationship between social support and NPS (β = -0.219; confidence interval: -0.291, -0.153); sleep quality moderated the relationship between psychological resilience and social support (β = 0.141, p < 0.001); and anxiety moderated the relationship between social support and NPS (β = -0.117, p = 0.019), as well as that between psychological resilience and NPS (β = -0.189, p < 0.001). These findings highlight the potential of exploring resilience-focused interventions and their effects on social support and NPS in older adults with MBI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of dementia has been increasing worldwide1, and this condition has emerged as the fifth-leading cause of death globally2. In this context, early identification of at-risk individuals is critical. As a prodromal phase of dementia, mild behavioral impairment (MBI) is a concept aimed at predicting the progression to dementia even before the onset of cognitive symptoms. MBI is defined as a behavioral disturbance that does not meet the NINCS-ADRDA3 criteria for Alzheimer’s dementia, Lund and Manchester criteria4 for frontotemporal dementia (FTD), DLB International Consortium criteria5 for Lewy body dementia (DLB), and the DSM-IV criteria6 for psychosis or another major psychiatric condition. The diagnosis of MBI is based on the following criteria: (i) presence of persistent behavioral changes and mild psychiatric symptoms, especially disinhibition; (ii) no severe memory impairment; (iii) no difficulty in activities of daily living; and (iv) no dementia. The frequency of neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) is high in all stages of dementia. One study by Castillo-García et al.7 indicated that the prevalence of NPS tended to be the highest in the more advanced stages of dementia that present with worse functionality. Matsuoka et al.8 observed that these symptoms severely affect the daily functioning and social capabilities of older adults with MBI. A cross-sectional survey conducted by Taragano et al.9 found that the risk of progression from MBI to dementia is 8.07 times higher than that of other psychiatric disorders and that 71.5% of older adults with MBI eventually progressed to dementia, which was significantly higher than the corresponding proportion (59.6%) among patients with only mild cognitive impairment. These data highlight the importance of early identification of MBI. By accurately predicting the risks of diseases, healthcare professionals can formulate timely and targeted preventive and intervention strategies. While the etiology of NPS is multifactorial, emerging evidence10,11 highlights social support as a modifiable protective factor for brain health in older adults. Social support12 is a multidimensional concept referring to practical, emotional, or tangible assistance derived from interpersonal relationships within social networks (e.g., family, friends, caregivers), which helps individuals cope with stressors and fosters feelings of esteem, inclusion, and understanding. Sippel et al.13 proposed that positive social support systems can enhance psychological resilience by increasing self-confidence or activating the parasympathetic nervous system and other neurobiological mechanisms, thereby maintaining individual physical and mental health. Specifically, for older adults with MBI, the level of social support directly influences the severity of NPS, as reported by Burley et al.14. Their study also revealed that insufficient social support is a crucial factor exacerbating the severity of NPS in older adults with MBI, while ample social support can effectively mitigate these symptoms.

A growing body of evidence has demonstrated that good social support correlates with better emotional regulation15. The well-established relationship between anxiety and dementia conversion is especially relevant, with multiple studies indicating that anxiety can increase the rate of conversion to dementia16,17. Specifically, individuals exhibiting heightened anxiety have a 48% higher risk of developing dementia18. Importantly, dysregulation of the neural systems underlying the manifestation of anxiety can result in excessive or inappropriate biobehavioral responses to perceived threats, potentially leading to the manifestation of several psychopathologies19. Older adults who experience long-term anxiety often perceive less social support, which, in turn, aggravates their NPS, as discussed by Yin et al.20. Since older adults with MBI frequently exhibit emotional instability and social adaptation disorders, these findings are particularly relevant for this population. Experiments by Kosel et al.21 on Canadian TgCRND8 Alzheimer’s mice further confirmed that enriching the environment can alleviate behavioral symptoms by increasing exploratory behavior and reducing anxiety-related behaviors. Tolchin et al.22 noted that the complex interplay between cognitive impairment and NPS involves multiple biological, psychological, and social factors. Collectively, these studies have elucidated the relationship between social support and NPS, indicating that strengthening social support may help reduce anxiety levels, thereby alleviating the severity of NPS in older adults with MBI. However, additional research is warranted to definitively confirm these findings, especially in relation to the unique needs and challenges faced by older adults with MBI.

Psychological resilience refers to the ability of an individual to mobilize internal and external resources to cope with adverse environments when facing setbacks, trauma, and stress23. Research by Guerrero et al.24 showed that older adults with higher levels of psychological resilience are less likely to exhibit NPS, while those with lower psychological resilience are more prone to these symptoms. However, direct evidence demonstrating the influence of psychological resilience levels on NPS in older adults with MBI is currently lacking25. Resilience is not a static trait but rather a dynamic process shaped by a combination of risk and protective factors26. In older adults, anxiety acts as a key risk factor that affects the level of psychological resilience27, while individuals with higher psychological resilience often display fewer symptoms of anxiety28. Jalilianhasanpour et al.29 highlighted the interplay of resilience, anxiety, and NPS, mentioning that anxiety may exacerbate the decline in psychological resilience. However, the influence of anxiety on the relationship between psychological resilience and NPS in older adults with MBI is unclear.

Beyond psychological factors, the association between social support and favorable sleep outcomes is backed by multiple studies30,31. A web-based empirical study on sleep disorders in the Chinese population showed that individuals with poorer self-perceived economic status and those living farther from community health services were more likely to have sleep problems32. These groups also tended to have lower psychological resilience and lower levels of social support33,34, reinforcing the notion that sleep quality is closely tied to both resilience and social support. Van35 proposed that good sleep quality significantly increases psychological resilience. Berkman’s social relations model36 suggests that social participation, as a downstream factor of social relations, can have a positive effect on mental health and health behaviors to promote sleep. For older adults with MBI, higher psychological resilience may alleviate NPS, and sleep quality can be reasonably considered to moderate the effect of social support on psychological resilience.

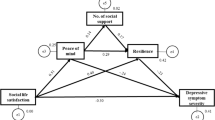

In summary, psychological resilience and social support are generally associated with a lower probability of NPS in older adults. However, the mechanisms underlying these relationships, especially in older adults with MBI, remain unclear. While existing research suggests that psychological resilience may directly reduce NPS and mediate the protective effects of social support, the potential moderating roles of anxiety and sleep quality in these pathways have not been thoroughly examined. To address these gaps, this study investigated the interplay among psychological resilience, social support, and NPS in older adults with MBI, proposing a moderated mediation model grounded in prior empirical research rather than a single theoretical framework. Through this approach, we aimed to determine (1) whether psychological resilience mediates the link between social support and NPS; (2) whether anxiety moderates the relationships of both social support and resilience with NPS; and (3) whether sleep quality moderates the effect of social support on psychological resilience. By testing these hypotheses, the study aimed to clarify the complex interactions shaping NPS risk in this vulnerable population, offering insights for targeted interventions.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study in nine cities in Fujian Province, southeastern China. To obtain a representative sample of older adults, we used multistage stratified whole-population sampling to select individuals aged ≥ 60 years from 42 nursing homes for older adults across nine cities. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) age ≥ 60 years; (2) meeting the ISTAART diagnostic criteria for MBI (Appendix S1)37, with MBI considered to be present when the Mild Behavioural Impairment Checklist (MBI-C) score was ≥ 1; (3) no significant visual or hearing impairments; (4) verbal communication skills sufficient to complete the scale assessments; and (5) voluntary participation in this study. The exclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) severe physical illnesses that could prevent the participants from completing the cognitive function screening, and (2) other neurological disorders that could cause cerebral dysfunction and severe medical illnesses. The study was conducted from June to October 2023. Forty-two nursing homes with more than 5693 residents were included in our study. A total of 1118 older adults were surveyed, and after excluding 423 older adults with combined mental disorders and 355 with MBI-C scores less than 1, 328 older adults were ultimately included in this study. More details on participant recruitment are shown in Fig. 1.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics

The sociodemographic characteristics recorded in this study included age, sex, education level, marital status, state of residence, occupation before retirement, history of diabetes, history of hypertension, history of coronary heart disease, history of chronic pain, history of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), psychiatric drug use, smoking, alcohol consumption, eating habits, smartphone use, participation in physical activity, and participation in recreational activity.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms

NPS was evaluated using the validated Chinese version of MBI-C, which was translated by Peking University Sixth Hospital’s Memory Center. This checklist consists of 34 items across five dimensions, with yes and no responses for each entry. The responses were scored on a three-point scale from mild to severe, with a total score of ≥ 1 indicating the presence of MBI37. The MBI-C has shown good reliability in Chinese clinical samples38.

Social support

Social support was evaluated using the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), which evaluates three dimensions using 10 items rated on a 4-point scale. Higher scores denote greater support, with scores below 20 indicating low support, 20–30 indicating average support, and 30–40 indicating satisfactory support39. The SSRS has demonstrated strong psychometric properties in the Chinese population40.

Psychological resilience

Psychological resilience was measured using the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10). The CD-RISC-10 contains 10 items rated on a 5-point scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always), with a total score of 40, where higher scores reflect greater resilience. The CD-RISC-10 demonstrates strong psychometric properties and has been extensively validated in the Chinese population41.

Anxiety

Anxiety was evaluated by the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS). The SAS includes 20 items rated on a 4-point scale. Scores range from “seldom” to “always,” which were converted to a total score of 100 by multiplying the raw score by 1.25. Higher scores indicate greater anxiety: a score ≥ 50 indicates the presence of anxiety, with scores of 50–59, 60–69, and ≥ 70 indicating mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively42. The Chinese version has shown strong psychometric properties in clinical settings43.

Sleep quality

Sleep quality of patients in the past month was assessed by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The PSQI consists of 18 items across seven dimensions that are scored on a 4-point scale to yield total scores ranging from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicate poorer sleep quality, which is categorized as follows: scores > 5 indicate poor sleep quality; 6 to 10, mildly poor sleep quality; 11 to 15, moderately poor sleep quality; and 16 to 21, severely poor sleep quality44. The PSQI has shown strong reliability and validity in the Chinese population45.

Data collection

The study design and procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from our university’s ethics committee, and permission was granted by the hospital manager and human resources department after a comprehensive explanation of the study’s purpose and procedures. All participants were fully informed about the study objectives and provided written informed consent. Participation was voluntary, and participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any consequences. Participants were instructed to complete the questionnaire independently, and if a participant needed assistance with the questionnaire, the researcher provided verbal explanation. Data collection for each participant required approximately 40 to 50 min. Before completing the data collection procedure, the researcher checked the integrity of the entire questionnaire. To ensure privacy, all collected data were kept strictly confidential.

Data analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). In two-tailed tests, p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Participants’ characteristics were described using mean ± standard deviation (SD) values for continuous variables and frequency (percentage) values for categorical variables. The correlations of study variables (social support, sleep quality, psychological resilience and anxiety) were analyzed by Pearson correlation analyses.

Before data analysis, scores for social support, psychological resilience, sleep quality, anxiety, and NPS were standardized. The analysis was conducted using Model 28 in PROCESS version 4.2.

To test the significance of the indirect effects, a bootstrap approach with 5000 samples was employed to generate bias-corrected bootstrap 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A significant indirect effect was indicated if the bias-corrected 95% CI did not include zero46.

After adjusting for all covariates (marital status, chronic pain, use of psychotropic drugs, diabetes mellitus, smartphone use, physical exercise, recreational or intellectual activities), a moderated mediation model was tested with social support as the predictor, psychological resilience as the mediator, and NPS as the outcome variable. Sleep quality moderated the relationship between the independent and mediator variables, and anxiety moderated the relationship between the independent and dependent variables as well as those between the mediator and dependent variables. A simple slope test was used to examine the significance of the moderating effect or interaction.

Results

Participants

A total of 1,118 older adults were surveyed in this study, and valid data were obtained from 1,106 participants (recovery rate, 98.9%). After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 328 older adults with MBI (29.66%; mean age, 78.2 years; 60.67% aged 80–89 years) were included in the study. Among these 328 older adults, 186 were currently single, divorced, or widowed (56.71%). The majority of these older adults were not living alone (74.39%) (Table 1).

Correlation analysis

The correlation matrix of the key study variables is shown in Table 2. Sleep quality was negatively correlated with social support (r = −0.146, p < 0.01). Psychological resilience showed a significant positive correlation with social support (r = 0.476, p < 0.001) and a significant negative correlation with sleep quality (r = −0.453, p < 0.001). Anxiety showed a significant positive correlation with sleep quality (r = 0.608, p < 0.001) and significant negative correlations with social support (r = −0.349, p < 0.001) and psychological resilience (r = −0.638, p < 0.001). NPS showed significant positive correlations with sleep quality (r = 0.378, p < 0.001) and anxiety (r = 0.567, p < 0.001) and significant negative correlations with social support (r = −0.432, p < 0.001) and psychological resilience (r = −0.561, p < 0.001). Therefore, the mediating effects of these five variables were further analyzed in this study.

Testing the mediation model

The regression analyses for the mediated moderation model are presented in Fig. 2 and Appendix S2. According to Model 1 and Model 4, social support positively predicted psychological resilience (β = 0.478, p < 0.001) and negatively predicted NPS (β = −0.137, p < 0.001). Psychological resilience negatively predicted NPS (β = −0.432, p < 0.001). Bootstrap results confirmed the mediating effect of psychological resilience between social support and NPS (indirect effect = −0.207, 95% CI [−0.289, −0.133]).

In a further exploration of the regulatory effects of poor sleep and anxiety, according to Model 3, the simple slope test results (see Appendix S3 and Appendix S4) indicated that the interaction between social support and poor sleep quality significantly predicted psychological resilience (β = 0.141, p = 0.001). This finding established the regulatory role of poor sleep between social support and psychological resilience. The predictive effect of social support on psychological resilience for mildly poor sleep quality (β = 0.315, p < 0.001) was different from that for highly poor sleep quality (β = 0.597, p < 0.001).

To more clearly elucidate the essence of the interaction effect between anxiety and psychological resilience, anxiety was categorized into high and low levels. Subsequently, a simple slope test was conducted, and a simple effect analysis graph was plotted (see Appendix S5 and Appendix S6). According to Model 7, the interaction between social support and anxiety significantly predicted NPS (β = −0.117, p = 0.019), establishing the moderating effect of anxiety on the relationship between social support and NPS. At mild anxiety, social support was not a significant predictor of NPS (β = −0.019, p = 0.774). At high anxiety, social support significantly predicted NPS (β = −0.254, p = 0.002). The interaction between psychological resilience and anxiety significantly predicted NPS (β = −0.189, p < 0.001), establishing the moderating effect of anxiety on the relationship between psychological resilience and NPS. Psychological resilience was a non-significant predictor of NPS at mild anxiety (β = −0.061, p = 0.418), but a significant predictor at severe anxiety (β = −0.440, p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study was conducted in a nursing facility to specifically address NPS in older adults with MBI. Conducting the study in this setting allowed for a controlled environment, providing valuable insights into the management of NPS in this vulnerable population. The model was verified through regression and simple slope tests, examining the mediation effects of psychological resilience, social support, anxiety, sleep quality, and NPS in older adults with MBI. Psychological resilience in older adults with MBI was shown to mediate social support and NPS, and social support and NPS showed a stronger association in older adults with low levels of psychological resilience. In addition, poor sleep quality and anxiety was found to exacerbate the effects of these relationships. These findings highlight the critical importance of targeting psychological resilience and social support in treatment plans within nursing facilities to effectively reduce NPS and enhance the quality of life for older adults with MBI.

The findings from our study further supported the results of previous studies regarding the direct influence of social support level on NPS in older adults with MBI, showing a negative correlation between social support and the incidence of NPS. Previous research has shown that lower levels of social support are associated with a higher likelihood of NPS, but these studies did not specifically focus on older adults with MBI24,47. On the basis of the characteristics of our study participants, we hypothesize that these findings could be attributed to the following reasons: First, social support provides emotional comfort and validation, helping individuals cope with stress and emotional distress and making them feel less lonely and isolated. The study by Kotwal et al.48 found that social support acts as a protective factor in the early stages of cognitive decline, reducing the behavioral and psychological problems caused by worsening symptoms. Second, social support may encourage healthy lifestyle and behavior choices, such as better habits, regular exercise, and healthy eating, all of which contribute to maintaining good mental health49. Therefore, enhancing the level of social support is particularly important for alleviating NPS in older adults with MBI. The findings of the present study in older adults with MBI indicate that targeted interventions are crucial for managing NPS and improving their overall health.

In this study, psychological resilience mediated the link between social support and NPS in older adults with MBI, indicating that social support affects NPS through psychological resilience in this group. Previous studies, such as those by Pałasz A et al.50 and Park et al.51, have shown that social support and coping styles influence negative emotions and suicide risk through psychological resilience. Kim et al.52 also found that higher social support is associated with fewer depressive symptoms and better quality of life, and that these relationships are mediated by psychological resilience. Our study extends these findings specifically to older adults with MBI. Psychological resilience helps older adults with MBI recover and adapt in the face of adversity, consistent with the findings of the study by Sullivan53. Social support enhances psychological resilience by promoting psychological stability and emotional regulation, thereby reducing NPS54. Moreover, it promotes the adoption of more salutary coping strategies, preventing reliance on negative mechanisms that exacerbate NPS. Thus, psychological resilience mediates the positive effects of social support on NPS. When psychological resilience acts as a mediator, the effect of social support on NPS is enhanced through internal psychological changes, effectively reducing NPS. Understanding this mediating role is crucial for developing targeted interventions to enhance social support and psychological resilience in older adults with MBI.

Our study found that poor sleep quality moderates the relationship between social support and psychological resilience in older adults with MBI. Specifically, in situations involving poor sleep quality, the predictive effect of social support on psychological resilience was stronger. A review by Seo et al.55 indicates that, across most studies, social support showed a positive correlation with sleep quality. Bush et al.56 used a social defeat model in male mice and observed that differences in resilience are strongly associated with interindividual variability in sleep regulation. For older adults with MBI, our findings in a previous study suggested that poor sleep quality may affect brain function, particularly in areas involved in emotional and cognitive processing, such as the prefrontal cortex57. As observed in the present study, the differential impact of social support on psychological resilience across varying levels of sleep quality further underscores the importance of social support in mental health, particularly in scenarios involving additional stressors such as sleep disorders.

Another key finding is that high anxiety significantly enhances the positive effect of social support on NPS in older adults with MBI through moderation, while mild anxiety does not. This implies that social support becomes more crucial and significantly predicts an increase in NPS only in situations involving severe anxiety. Tolchin B22 also described that anxiety, social support, and NPS were linked, but our study further refines this conclusion, specifically focusing on older adults with MBI in nursing home settings. The possible explanations for these findings are as follows: First, social support may affect NPS by altering the levels of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine50. In patients with high anxiety levels, changes in the levels of these neurotransmitters may be more drastic, making the positive effects of social support more significant. Second, high levels of anxiety are usually associated with high stress states in the body58. Social support may reduce the stress response by lowering the levels of stress hormones (e.g., cortisol), yielding more pronounced psychological and physiological improvements for individuals with high anxiety. In contrast, individuals with lower levels of anxiety are less sensitive to social support. Considering the absence of additional neuropathological studies in this area, more neurobiological and psychological studies are needed to validate and explore this finding in depth.

Moreover, anxiety levels moderated the effect of psychological resilience on NPS in older adults with MBI. Specifically, psychological resilience significantly predicted NPS under severe anxiety but not under mild anxiety. The study by Matsuoka8 explored psychological resilience in caregivers of patients with mild and moderate Alzheimer’s disease and found that psychological resilience is influenced by factors such as anxiety and depression, depending on the severity of the disease. However, our study specifically targeted older adults with MBI and was conducted in nursing homes, which may have been responsible for the differences in results. One possible reason for this moderation effect is that high anxiety depletes psychological resources59. During severe anxiety, individuals’ psychological resources (e.g., attention and emotion regulation) may be overly taxed, making psychological resilience more critical. Those with high psychological resilience can cope with stress more efficiently, significantly predicting NPS under severe anxiety. Conversely, in situations involving mild anxiety, individuals typically have sufficient psychological and emotional resources to manage daily stress, diminishing the role of psychological resilience. Mild anxiety alone may be sufficient to help individuals maintain a stable psychological state, reducing the relative importance of psychological resilience.

This study has several strengths. First, it was conducted in a nursing home setting, which provided a relatively controlled environment and consistent caregiving conditions. This minimized variability associated with caregiver differences and daily routines, thereby enhancing the reliability of the observed associations. Second, the study systematically examined the relationships among NPS, social support, psychological resilience, sleep quality, and anxiety in older adults with MBI. This multidimensional approach offers a more comprehensive understanding of the psychosocial factors associated with NPS in this population. Taken together, the findings underscore the importance of targeting psychological resilience and social support in the care of older adults with MBI. Interventions aimed at enhancing these factors—particularly within institutional settings—may help alleviate behavioral symptoms and improve overall quality of life. Future research should be extend to investigate these relationships in community-dwelling populations and adopt longitudinal designs to clarify causal pathways.

However, this study has some limitations. First, a substantial number of individuals were excluded due to communication barriers related to the widespread use of various dialects in Fujian Province. Future research may benefit from developing dialect-specific assessment tools to improve inclusivity and representativeness. Second, mood and anxiety symptoms are assessed in the MBI-C, which served as the outcome variable, their partial overlap may affect the interpretation of the results. Therefore, caution is warranted when interpreting these findings. Third, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits our ability to draw causal inferences or assess changes over time. Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the dynamic relationships among social support, psychological resilience, sleep quality, anxiety, and neuropsychiatric symptoms in older adults with MBI. Fourth, although participants’ global cognitive functioning was assessed to exclude dementia, specific cognitive domains—such as executive function and social cognition—were not evaluated. These unmeasured cognitive variables may influence the associations among key psychosocial factors and neuropsychiatric symptoms, limiting the depth of our analysis. Despite these limitations, our findings provide meaningful insights for the management of older adults with MBI in nursing home settings. Specifically, they highlight the importance of enhancing social support and fostering psychological resilience as potential strategies to mitigate neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Conclusions

The findings of this study emphasize the influence of social support on NPS in patients with MBI, indicating an urgent need for safe and effective treatments and management approaches. In addition, the results of mediation analyses more clearly revealed the mediating role of psychological resilience between social support and NPS, indicated that poor sleep quality moderated the effects of social support and psychological resilience, and showed that anxiety moderated the relationship between social support and NPS and that between psychological resilience and NPS. These findings will facilitate the development of non-pharmacological treatments for NPS in older adults with MBI and further contribute to the ultimate goal of preventing and delaying the onset and progression of dementia.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study is available from the corresponding author on request.

6.References

Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2018 (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2018).

GBD 2016 Dementia Collaborators. Global, regional, and National burden of alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18 (1), 88–106 (2019).

McKhann, G. et al. Clinical diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of department of health and human services task force on alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 34 (7), 939–944 (1984).

Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. The Lund and Manchester groups. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 57 (4), 416–418 (1994).

McKeithIG et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology 47 (5), 1113–1124 (1996).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders(4th ed.). Washington, DC.

Castillo-García, I. M. et al. Clinical trajectories of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Mild-Moderate to advanced dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 86 (2), 861–875 (2022).

Matsuoka, T., Ismail, Z. & Narumoto, J. Prevalence of mild behavioral impairment and risk of dementia in a psychiatric outpatient clinic. J. Alzheimers Dis. 70 (2), 505–513 (2019).

Taragano, F. E. et al. Risk of conversion to dementia in a mild behavioral impairment group compared to a psychiatric group and to a mild cognitive impairment group. J. Alzheimers Dis. 62 (1), 227–238 (2018).

Lin, N., Simeone, R. S., Ensel, W. M. & Kuo, W. Social support, stressful life events, and illness: a model and an empirical test. J. Health Soc. Behav. 20 (2), 108–119 (1979).

Duffner, L. A. et al. Associations between social health factors, cognitive activity and neurostructural markers for brain health - A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 89, 101986 (2023).

Cohen, S. Social relationships and health. Am. Psychol. 59 (8), 676–684 (2004).

Costa, A. L. S. et al. Social support is a predictor of lower stress and higher quality of life and resilience in Brazilian patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Nurs. 40 (5), 352–360 (2017).

Burley, C. V., Casey, A. N., Chenoweth, L. & Brodaty, H. Views of people living with dementia and their families/care partners: helpful and unhelpful responses to behavioral changes. Int. Psychogeriatr. 35 (2), 77–93 (2023).

Kehoe, L. A. et al. Associations of quality of social support and accurate beliefs about curability among older adults with advanced cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 15 (8), 102061 (2024).

Lyketsos, C. G. et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7 (5), 532–539 (2011).

Mah, L., Binns, M. A., Steffens, D. C. & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Anxiety symptoms in amnestic mild cognitive impairment are associated with medial Temporal atrophy and predict conversion to alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 23 (5), 466–476 (2015).

Pentkowski, N. S., Rogge-Obando, K. K., Donaldson, T. N., Bouquin, S. J. & Clark, B. J. Anxiety and alzheimer’s disease: behavioral analysis and neural basis in rodent models of alzheimer’s-related neuropathology. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 127, 647–658 (2021).

McEwen, B. S., Eiland, L., Hunter, R. G. & Miller, M. M. Stress and anxiety: structural plasticity and epigenetic regulation as a consequence of stress. Neuropharmacology 62 (1), 3–12 (2012).

Yin, S., Yang, Q., Xiong, J., Li, T. & Zhu, X. Social support and the incidence of cognitive impairment among older adults in china: findings from the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey study. Front. Psychiatry. 11, 254 (2020).

Kosel, F., Pelley, J. M. S. & Franklin, T. B. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in mouse models of alzheimer’s disease-related pathology. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 112, 634–647 (2020).

Tolchin, B., Hirsch, L. J. & LaFrance, W. C. Jr. Neuropsychiatric aspects of epilepsy. Psychiatr Clin. North. Am. 43 (2), 275–290 (2020).

Wermelinger Ávila, M. P. et al. Resilience and mental health among regularly and intermittently active older adults: results from a Four-Year longitudinal study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 41 (8), 1924–1933 (2022).

Guerrero, J. M., Gutiérrez, B. & Cervilla, J. A. Psychotic symptoms associate inversely with social support, social autonomy and psychosocial functioning: A community-based study. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 68 (4), 898–907 (2022).

Rutter, M. Resilience as a dynamic concept. Dev. Psychopathol. 24 (2), 335–344 (2012).

Zhang Haimiao, Z., Yongai, Z., Xiaolan, Z. & Lu Predictive factors affecting psychological resilience in urban empty nesters. Public. Health Prev. Med. 29 (03), 141–144 (2018).

Zhang Jingfeng, Z. & Jianxin, Z. Neighborhood characteristics and older adults’well-being: the roles of sense of community and personal resilience. Soc. Indic. Res. 12 (4), 1–15 (2017).

Durán-Gómez, N. et al. Understanding resilience factors among caregivers of people with alzheimer’s disease in Spain. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 13, 1011–1025 (2020).

Jalilianhasanpour, R. et al. Resilience linked to personality dimensions, alexithymia and affective symptoms in motor functional neurological disorders. J. Psychosom. Res. 107, 55–61 (2018).

Kent de Grey, R. G., Uchino, B. N., Trettevik, R., Cronan, S. & Hogan, J. N. Social support and sleep: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 37, 787–798 (2018).

Xiao, H., Zhang, Y., Kong, D., Li, S. & Yang, N. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med. Sci. Monit. 26, e923549 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances and associated factors among Chinese residents: A web-based empirical survey of 2019. J. Glob Health. 13, 04071 (2023).

Popa-Velea, O., Pîrvan, I. & Diaconescu, L. V. The impact of Self-Efficacy, optimism, resilience and perceived stress on academic performance and its subjective evaluation: A Cross-Sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18 (17), 8911 (2021).

Wyngaerden, F., Vacca, R., Dubois, V. & Lorant, V. The structure of social support: a multilevel analysis of the personal networks of people with severe mental disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 22 (1), 698 (2022).

Van, K. The ability of older adults to overcome adversity: a review of the resilience concept. Geriatr. Nurs. 34 (2), 122–127 (2013).

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I. & Seeman, T. E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 51 (6), 843–857 (2000).

Ismail, Z. et al. ISTAART neuropsychiatric symptoms professional interest area. neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioral impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 12 (2), 195–202 (2016).

Xu, L. et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of mild behavioral impairment checklist in mild cognitive impairment and mild alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 81 (3), 1141–1149 (2021).

Hou, T. et al. Social support and mental health among health care workers during coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: A moderated mediation model. PLoS One. 15 (5), e0233831 (2020).

Shen, Z., Ding, S., Shi, S. & Zhong, Z. Association between social support and medication literacy in older adults with hypertension. Front. Public. Health. 10, 987526 (2022).

Tu, Z. et al. Psychometric properties of the 10-item Connor-Davidson resilience scale in Chinese military personnel. Front. Psychol. 14, 1163382 (2023).

Dunstan, D. A. & Scott, N. Norms for zung’s Self-rating anxiety scale. BMC Psychiatry. 20 (1), 90 (2020).

Shao, R. et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety and correlations between depression, anxiety, family functioning, social support and coping styles among Chinese medical students. BMC Psychol. 8 (1), 38 (2020).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F. 3rd, Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28 (2), 193–213 (1989).

Liu, X. et al. The mediation role of sleep quality in the relationship between cognitive decline and depression. BMC Geriatr. 22 (1), 178 (2022).

Qiao, X. et al. The association between frailty and medication adherence among community-dwelling older adults with chronic diseases: medication beliefs acting as mediators. Patient Educ. Couns. S0738-3991 (20), 30279–30272 (2020).

Huang, X. Q., Zhang, H. & Chen, S. Neuropsychiatric symptoms, parenting stress and social support in Chinese mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Curr. Med. Sci. 39 (2), 291–297 (2019).

Kotwal, A. A., Kim, J., Waite, L. & Dale, W. Social function and cognitive status: results from a US nationally representative survey of older adults. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 31 (8), 854–862 (2016).

Thoits, P. A. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 52 (2), 145–161 (2011).

Pałasz, A., Menezes, I. C. & Worthington, J. J. The role of brain gaseous neurotransmitters in anxiety. Pharmacol. Rep. 73 (2), 357–371 (2021).

Park, S. et al. The association of suicide risk with negative life events and social support according to gender in Asian patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 228 (3), 277–282 (2015).

Kim, B., Jun, H., Lee, J., Kim, Y. M. & Social Support Activities of daily living, and depression among older Japanese and Koreans immigrants in the U.S. Soc. Work Public. Health. 35 (4), 163–176 (2020).

Sullivan, K. A., Kempe, C. B., Edmed, S. L. & Bonanno, G. A. Resilience and other possible outcomes after mild traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 26 (2), 173–185 (2016).

Chang, Y. H., Yang, C. T. & Hsieh, S. Social support enhances the mediating effect of psychological resilience on the relationship between life satisfaction and depressive symptom severity. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 4818 (2023).

Seo, S. & Mattos, M. K. The relationship between social support and sleep quality in older adults: A review of the evidence. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 117, 105179 (2024).

Bush, B. J. et al. Non-rapid eye movement sleep determines resilience to social stress. Elife 11, e80206 (2022).

Hultman, R. et al. Dysregulation of prefrontal Cortex-Mediated Slow-Evolving limbic dynamics drives Stress-Induced emotional pathology. Neuron 91 (2), 439–452 (2016).

Zalachoras, I. et al. Opposite effects of stress on effortful motivation in high and low anxiety are mediated by CRHR1 in the VTA. Sci. Adv. 8 (12), eabj9019 (2022).

Pellerin, N., Raufaste, E., Corman, M., Teissedre, F. & Dambrun, M. Psychological resources and flexibility predict resilient mental health trajectories during the French covid-19 lockdown. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 10674 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study and patient advisers for their support. The authors would also like to thank nursing homes and those who contributed to the study by recruiting patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yanhong Shi and Zixin Fang are joint first authors. Study design: HL, Yanhong Shi, Yuanjiao Yan and Rong Lin. Data collection: Yanhong Shi, Yuanjiao Yan, Danting Chen, Ziping Zhu, Xiaozhen Fu, Bingjie Wei, Zhengmin Wang, Shaobo Wu and Zixin Fang. Data analysis: Yanhong Shi, Yuanjiao Yan, Danting Chen, Ziping Zhu, Xiaozhen Fu, Bingjie Wei, Zhengmin Wang, Shaobo Wu and Chenshan Huang. Manuscript preparation and approval: Hong Li, Yanhong Shi, Zixin Fang, Yuanjiao Yan, Rong Lin and Chenshan Huang.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Review Committee of Fujian Medical University (2023 − 177).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Y., Fang, Z., Chen, D. et al. Relationship between neuropsychiatric symptoms and social support in older adults with mild behavioral impairment: a moderated mediation model. Sci Rep 15, 32904 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17516-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17516-x