Abstract

Microtubules (MTs) play a crucial role in mitosis and are composed of α-/β-tubulin heterodimeric subunits. In eukaryotes, eight α-tubulin and ten β-tubulin isotypes have been reported, each displaying tissue-specific expression patterns. Among them, the βIII-tubulin isotype is significantly overexpressed in various cancers and is closely associated with resistance to anticancer agents, making it an attractive target for cancer therapies. This study employed a comprehensive approach integrating structure-based drug design, machine learning, ADME-T and PASS biological property evaluations, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations to identify potential natural compounds targeting the ‘Taxol site’ of the αβIII-tubulin isotype. Screening of 89,399 compounds from the ZINC natural compound database yielded 1,000 initial hits based on binding energy. Further, refinement using machine learning classifiers narrowed down these to 20 active natural compounds, of which four - ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577, ZINC08952607, and ZINC03847075 exhibited exceptional ADME-T properties and notable anti-tubulin activity. Molecular docking revealed significant binding affinities of these compounds to the ‘Taxol site’ of the αβIII-tubulin isotype. Molecular dynamics simulations evaluated using RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and SASA analysis, revealed that these compounds significantly influenced the structural stability of the αβIII-tubulin heterodimer compared to the apo form of the αβIII-tubulin isotype. Moreover, binding energy calculations showed a decreasing order of binding affinity for αβIII-tubulin; ZINC12889138 > ZINC08952577 > ZINC08952607 > ZINC03847075. In conclusion, this study identified natural compounds against drug resistant αβIII-tubulin isotype. These findings offer a promising foundation for developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting carcinomas associated with βIII-tubulin overexpression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

MTs play an essential role in mitosis, intracellular transport, cell signaling, and cell movement1. Hence, MTs are considered as an important target for designing a potential anticancer agent2. MTs are composed of α-tubulin and β-tubulin heterodimeric subunits. In humans, a total of eight α-tubulin and ten β-tubulin isotypes have been identified to exist in human, each exhibiting tissue-specific expression patterns3. MTs targeting anticancer agents bind to specific sites on the tubulin, such as the Vinca, Colchicine, Non-taxane, Taxoid and Maytansine sites and thereby binding modulates its structure and dynamics4,5,6. However, mutation in β-tubulin, overexpression of p-glycoprotein drug efflux pump and specific β-tubulin isotype affects the efficacy of anti-tubulin agents7.

Taxol, an FDA-approved microtubule-stabilizing agent8,9is used to treat various carcinomas, including ovarian10,11breast12lung cancers13 and several others. However, the expression of the βIII tubulin isotype in several carcinomas reduces sensitivity to Taxol by altering microtubule dynamics and impairing the drug’s ability to bind and stabilize them. Previous study involving 98 ovarian cancer patients indicated that βIII tubulin isotype expression is associated with resistance to Taxol, while down-regulation of βIII enhances responsiveness to the treatment14. Similarly, analysis of 41 advanced ovarian cancer patients showed significant up-regulation of βIII tubulin isotype and overexpression of the MDR-1 gene15. To further investigate the role of βIII tubulin in Taxol resistance, small interfering RNA (siRNA) was used to silence βIII expression in two non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines, NCI-H460 and Calu-6, resulting in increased sensitivity to Paclitaxel, Vincristine, and Vinorelbine16. The A549-T24 NSCLC cell line, resistant to Taxol, exhibited a 17-fold increase in resistance and a fourfold increase in βIII expression compared to the parental A549 cells17. High levels of βIII tubulin are associated with reduced susceptibility to taxane-based chemotherapy in ovarian cancer18,19 and are also correlated with decreased survival rates in NSCLC20breast cancer21colon cancer22and cancers of unknown primary origin23. Recently, several drugs targeting Taxane site, including Tesetaxel, TPI-287, EPO906, and ZK219477, have entered clinical trials24,25. Additionally, natural products such as Protopine26Protuboxepin A27and Fisetin28 have demonstrated potential as microtubule-stabilizing agents. However, βIII-tubulin isotype-specific drugs have not yet been developed for clinical use. In addition to drugs targeting the Taxol site, other agents that bind to tubulin sites, such as Eribulin29non-taxane30Indanocine31and DAMA-colchicine32also encounter resistance due to the overexpression of the βIII tubulin isotype.

Previously, Zhang et al. utilized a multi-step computational and experimental approach to identify potent anti-tubulin compounds, successfully highlighting tubulin-hit 8 and tubulin-hit 30 as promising candidates exhibiting significant anti-tubulin activity33. Similarly, novel paclitaxel-mimicking alkaloids with 5-7-6 tricyclic scaffolds were synthesized, with alkaloid 2 exhibiting potent activity against drug-sensitive and resistant cancer cell lines. MD simulations revealed structural stability differences between alkaloid 2 and REDOR-Taxol, guiding design improvements34. Similarly, molecular docking analysis identified etoposide as the most effective tubulin-targeting anticancer drug35. Also, colchicine-site-targeting tubulin modulator was designed via ensemble pharmacophore-based screening, yielding tetrazole 5, which inhibited tubulin polymerization and showed nano molar anti-proliferative activity against HeLa cells36. Additionally, seven novel microtubule stabilizers were discovered using molecular modelling and in vitro assays, demonstrating enhanced tubulin interactions, MT assembly promotion, and moderate cytotoxicity in HeLa cells, validating this rational discovery approach37. Earlier, computational modelling approach was utilized to identify the potential inhibitors38,39and also effect of mutation on drug binding40.

In this study, we employed a structure-based drug design protocol as mentioned in the Fig. 1 which includes homology modelling, drug library preparation, high-throughput virtual screening, machine learning, PASS prediction, ADME-T analysis, and molecular dynamic simulations, to discover novel natural compounds with potential binding affinity for ‘Taxol site’ of the human βIII tubulin isotype. This approach aims to identify potential anti-tubulin agents that specifically target the βIII tubulin isotype, potentially aiding in the treatment of drug-resistant carcinomas.

Computational methodology

Homology modeling of human αβIII tubulin isotype

A homology modeling approach was employed to construct the three-dimensional atomic coordinates of human βIII tubulin isotype using Modeller 10.241. The sequence of human βIII tubulin isotype was retrieved from the Uniprot protein database (Uniprot ID: Q13509). The crystal structure of αIBβIIB tubulin isotype bound with Taxol (PDB ID − 1JFF.pdb, resolution 3.50 Å) was retrieved from the RCSB protein database for homology modeling as template structure. The 1JFF.pdb is crystallized from bovine source and shares 100% sequence identity with humans for β-tubulin. To model the αβIII tubulin isotype, we kept the αIB-tubulin unchanged (with GTP and Mg2+) and simply changed the modelled βIII tubulin isotype without changing the Taxol and GDP from crystal structure 1JFF.pdb using PyMol v2.5.0 (https://www.pymol.org/)42. This helps to maintain the natural binding pocket of the ligand. The homology model of βIII tubulin isotype was selected based on the DOPE (Discrete optimized protein energy) score, which is a statistical potential, optimized for model assessment. Further, the stereo-chemical quality of the βIII tubulin isotype was assessed using the Ramachandran plot through PROCHECK43 as shown in the Supplementary Fig. 1.

Structure based virtual screening (SBVS)

The natural compounds consisting of 89,399 were retrieved from the ZINC database for virtual screening (https://zinc12.docking.org/pdbqt/)44 in the SDF format. These SDF files were then converted into the PDBQT format using Open-Babel software45. In this study, virtual screening was performed targeting the ‘Taxol site’ of βIII tubulin isotype using the AutoDock Vina software46. It utilizes the advanced Vina scoring function to systematically evaluate extensive compound libraries. Next, InstaDock v1.0 software was used to identify possible hit compounds based on the binding energy47. It facilitates the filtering of ‘docked out files’ based on the binding affinity, allowing us to identify the top hits for subsequent analysis. Here, we selected the top 1000 hit compounds for machine learning process.

Identification of active compounds using machine learning (ML) approach

To identify potential active natural compounds among the above selected 1000 hits from virtual screening, we employed a ML approach. ML has the potential to speed up pharmaceutical research by identifying new and significant information from the massive amount of complex data produced throughout the drug discovery process48,49. This approach has been utilized in a variety of drug discovery methodologies, including molecular property, activity prediction, virtual screening and de novo drug design50. In this study, a supervised ML approach was employed based on their chemical descriptor properties to differentiate between active and inactive molecules51. This approach enabled the identification of potential drug compounds. Here, identified hit compounds based on their binding energy were considered as test datasets. While, for the training data set, Taxol site targeting drugs were considered as active compounds (Supplementary Table 1), while non-Taxol targeting drugs are considered as inactive compounds (Supplementary Table 2). The details of the training datasets are mentioned in the Supplementary Table 3. Next, Decoys were generated for this training dataset by using the Directory of Useful Decoys - Enhanced (DUD-E) server52. This tool helps to generate decoys from the given set of compounds that have similar physicochemical properties but different topologies53. Furthermore, test and training dataset was used to generate the molecular descriptor properties using the PaDEL-Descriptor54. PaDEL-Descriptor software calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints using the SMILE code of the compounds. The software generates 797 descriptors and 10 types of fingerprints54. These descriptors and fingerprints are primarily calculated using the Chemistry Development Kit54. It plays a pivotal role in transforming chemical structures into numerical representations, making them suitable for machine learning algorithms. This method is crucial for predicting chemical characteristics and designing novel compounds. Next, 5-fold cross-validation, based on the true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), and false negative (FN) data, we calculated several performance indices such as precision, recall, F-score, accuracy, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), TT, Kappa and Area Under Curve (AUC), for various machine learning (ML) models. The performance indices were calculated using the expressions described in the previous study54.

In general, better model performance is indicated by higher values for accuracy, precision, recall, specificity, F1-score, and AUC. The significance of Recall and Precision are crucial for evaluating the handling of false negatives and false positives54. While Accuracy and F1 Score provide an overall view of performance, they may be insufficient for imbalanced datasets. Metrics such as AUC, Kappa, and MCC offer deeper insights, especially in cases of dataset imbalance or when accounting for chance agreement. Additionally, TT (Sec) is a practical measure, emphasizing the computational efficiency and feasibility of effective models. Here, supervised machine learning (ML) model- AdaBoost55Logistic regression (LR)56Decision tree classifier (DT)57Random forest (RF)58Linear discriminant analysis (LDA)59Extra trees classifier (ET)60K Neighbors Classifier (KNN)61naive Bayes (NB)62Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (QDA)63Dummy Classifier64SVM- Linear kernel65and Ridge classifier was used to separate the active and inactive compounds from the both test and training dataset based on chemical descriptor properties classification66. Here, 20 active compounds were selected based on their highest probability score for further prediction and the details of selection criteria is described in the Supplementary Fig. 2.

PASS prediction

The Prediction of Activity Spectra for Substances (PASS) is a valuable tool for assessing biologically active compounds, enabling the identification of pharmacological effects and potential toxicities, including mutagenicity and carcinogenicity. PASS evaluation shows two different probabilities, ‘probability to be active (Pa)’ and ‘probability to be inactive (Pi)’67. Compounds are physiologically active if their Pa value is greater than their Pi value. Here, Way2drug webserver (http://www.way2drug.com/passonline/) was used for the prediction of PASS, biological activity of 20 active compounds selected from the ML process68.

ADME-T prediction

The absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination, and toxicity (ADME-T) properties of active compounds were predicted using the Swiss-ADME69 and pkCSM70 web server, respectively. ADME-T properties prediction is helpful in the selection of appropriate drug candidate71. Pharmacokinetics and drug-likeness activity of selected drug compounds such as human gastrointestinal absorption (GI), blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeation, skin penetration coefficient, permeability glycoprotein (P-gp), and hepatotoxicity were predicted.

Molecular Docking

The interaction of human αβIII tubulin isotype with selected active compounds was assessed using the molecular docking through AutoDock 4.2.372. Here, we used a local docking protocol, to investigate the binding mode of selected drug compounds with Taxol site of human αβIII tubulin isotype. For local docking, grid box with the dimension of 45 × 45 × 45 and spacing 0.375Å covering the Taxol site of βIII tubulin isotype was generated. The grid box offered ample space for translation and rotation of the selected compounds to achieve optimal binding conformation32. 100 runs were performed using the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA). The clusters were then compared based on the cluster size and binding energy calculated by the AutoDock4.2.3 scoring function. The lowest energy docked conformation was selected as the most stable conformation at the Taxol binding site of αβIII tubulin isotype. The PyMoL V2.5042 and Discovery Studio Visualizer were used to examine the binding poses and all potential interactions. The Discovery Studio Visualizer73 was used to examine atomic coordinates, types of interaction, and participation of residues in the interactions. Here, the compounds that interact specifically with the Taxol binding site of the human αβIII tubulin isotype were selected for further analysis.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

To explore the mode of interaction, stability and binding affinity of αβIII tubulin isotype with anticancer compounds, we performed MD simulations using GROMACS 2021.574. The AMBER ff99SB-force field parameters were utilized for the tubulin protein, and for the Mg2+, GDP, and GTP parameters were obtained from the AMBER parameter database75,76as similar to earlier study32. While force field parameters for the drug compound were generated using the “generalized AMBER force field” (GAFF) through Antechamber module of AmberTools22, similar to previous study32. Here, ‘Xleap’ module of AmberTools22 were used to generate the MD simulation systems. The αβIII tubulin-drug complexes were solvated using TIP3P water model in a cubic box and then neutralized by adding appropriate number of sodium (Na+) counter ions. The ‘Xleap’ generated ‘Prmtop’ and ‘Inpcrd’ files were further converted into GROMACS compatible topologies using the “ParmEd” tool77similar to earlier study78. All systems were then energy minimized using the steepest descent (5000 steps) and conjugate gradient (5000 steps) methods, to remove the strain energy on the systems. The NVT and NPT ensembles were further used to equilibrate all the systems for 1000 ps each. The temperature was maintained at 300 K using the velocity-rescale thermostat79 and pressure was kept constant at 1 bar using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat80. The production simulation was run on each system for 500 ns, and simulation trajectories were incremented for every 2-fs time step. During the simulation, a 1.0 nm cut-off distance, a 0.16 nm Fourier spacing, and a 4-interpolation order were employed. The LINCS algorithm was used to apply constraints on the H-bond lengths81. During the MD simulation, long-range electrostatic interactions were computed using the particle mesh Ewald (PME) approach82. The simulation trajectories were further analysed using the ‘XMGrace’83 and ‘Visual Molecular Dynamics’ (VMD) software’s84.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a potent statistical technique that is used in the field of biomolecular dynamics. It is particularly useful for visualizing and understanding the collective motions of biomolecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids85. The eigenvectors are a representation of the direction of the motion whereas eigenvalues indicate the amplitude of motion combined with the direction86. To calculate the covariance matrix for the PCA illustration, the GROMACS gmx_covar was utilized and to compute the overlap between the principal components and the trajectory coordinates, the gmx_anaeig tool was used74. The eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the covariance matrix were computed and diagonalized to identify the principal components of the simulation systems, which include the αβIII-tubulin and αβIII-tubulin with drugs.

Free energy landscape

Free Energy Landscape (FEL) was plotted to represent the conformational variability of a system by quantifying two key variables such as root mean square deviation and radius of gyration of the simulation system. The gmx sham tool74 facilitated the construction of the FEL87. The FEL visualization was performed using OriginLab software v2024b (OriginLab Version 2024, OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA.)

Pair distribution function (PDF) analysis

Pair Distribution Function (PDF) analysis was utilized to identify the specific atomic interactions within the selected drug compounds that most strongly associate with αβIII-tubulin. To achieve this, we utilized MD simulation trajectory of each αβIII-tubulin drug complex and subsequently calculated the PDFs. Generally, PDF indicates the probability of finding a particular particle at a specific distance from a chosen atom within the molecule under investigation88. Here, the output of the PDF denoted by a g(r) where r is the distance between the pair of atoms and g(r) is the density number of atoms at that distance relative to a reference ideal gas. Here g(r) = 1 indicates a random distribution, whereas g(r) > 1 suggests clustering or attraction between atoms at that distance. Similarly, g(r) < 1 indicates a depletion or avoidance of atoms at that distance. A higher probability, represented by a larger g(r) value, and a shorter distance signify a stronger interaction89. Furthermore, strong interactions are also characterized by sharply defined g(r) profiles. All PDFs pertaining to the interaction of the drug compound with αβIII-tubulin were analysed.

Binding energy calculation

To investigate the binding affinity of αβIII tubulin isotype with the selected drugs, we employed binding energy calculations using the Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) approach provided in the gmx_mmpbsa tool90. Binding energy was calculated of the last equilibrated 100ns MD simulation trajectory for each system. Entropy computations were not considered while determining the binding energy in this study, as it is computationally expensive, similar to earlier studies on tubulin and drug complexes78,91. To identify the active site residues contribution in the binding energy, the per-residue energy decomposition was also calculated.

Result & discussion

Homology modeling of human αβIII tubulin isotype

Homology model of the human βIII tubulin isotype was constructed using the αIBβIIB tubulin heterodimer (PDB ID: 1JFF) as template through Modeller 10.292. Here, 100 models of the βIII tubulin isotype were generated, and the best model was selected based on the DOPE (Discrete Optimized Protein Energy) score (−51589.82422). DOPE is a statistical potential optimized for model assessment, which calculates an “energy” score for a given protein model. Lower DOPE scores generally indicate higher-quality models. The stereo-chemical quality of the βIII tubulin was assessed using the Ramachandran plot through PROCHECK93 and results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The Ramachandran plot revealed that 88.1% of residues are in the most favoured region, 9.6% residues in the additional allowed region, 1.5% residues in the generously allowed region, and 0.8% residues in the disallowed region. This indicates that the model quality is suitable for further molecular modelling study, as total of 97.7% of residues are in the most favoured and additional allowed region. Further, the complete model of αβIII tubulin isotype was prepared by keeping the αIB-tubulin constant and changing only the βIII tubulin isotype from crystal structure 1JFF.pdb, similar to an earlier study32. Hereafter, the homology modeled αIBβIII tubulin heterodimer is referred to as αβIII tubulin isotype. This homology model of the human αβIII tubulin heterodimer was then utilized for structure-based virtual screening.

Structure-based virtual screening

Structure-based virtual screening is a computational method for identifying compounds with high binding affinity by analysing their binding energy and mode of interactions with a target protein94. Here, high-throughput virtual screening was performed by targeting the Taxol site of αβIII tubulin isotype through AutoDock Vina95 and compounds were filtered based on the binding affinities. A total of 1000 hit compounds were further selected with binding energy higher than − 10 kcal/mol. These hit compounds were further subjected to a machine learning approach, to identify the potential active compounds.

Identification of active compounds using machine learning

The present study employed the supervised ML approach, a widely used and highly effective method for separating active and inactive molecules from a test dataset. The virtual screening process, followed by hit identification, resulted in a total of 1000 hit compounds, which were considered as a test dataset. While, for the training dataset ‘Taxol site’ targeted and ‘non-Taxol site’ targeted drugs were considered as active and inactive datasets, respectively as shown in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

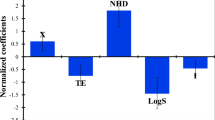

A total of 32 compounds were identified as active, and 26 compounds were identified as inactive for training dataset (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Next, DUD-E database was used to generate decoys for training dataset. Training dataset comprising 3030 decoys, delineated into 1580 active and 1450 inactive compounds. Next, chemical descriptor properties of the of test and training dataset were generated using the PaDEL Descriptor software54and further used to build a classification algorithm to identify chemical activity. PaDEL descriptor uses the SMILES file format to calculate the descriptor properties also known as features. Initially, the prepared dataset underwent pre-processing where a binary ‘Label’ column was created based on compound ‘Activity’, subsequently eliminating rows with missing ‘pIC50’ values and metadata columns were identified96. Subsequently, features containing zero or null values were excluded from the dataset to enhance computational efficiency. To ensure stratified sampling and preserve target class proportions, the remaining dataset was divided into training (75%) and testing (25%). We used the machine learning features of PyCaret97 and entailed setting up a baseline for feature selection, comparing models using Area under Curve (AUC)98,99shown in Table 1. Here, the prediction model was developed by using the following algorithms: AdaBoost, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), Light gradient boosting machine (LightGBM), CatBoost classifier (catboost), Gradient boosting classifier (gbc), Logistic regression (LR), Decision tree classifier (DT), Random forest (RF), Linear discriminant analysis (LDA), Extra trees classifier (ET), K Neighbors Classifier (KNN), naive Bayes (NB), Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (QDA), Dummy Classifier, SVM- Linear kernel, and Ridge classifier100.

In the process of training, we used a 5-fold cross-validation approach to estimate the models. From the dataset, the precision, recall, AUC, accuracy, MCC, TT, Kappa, and F-score were estimated. Here, Table 1 shows that several models achieved very high AUC scores, including: AdaBoost Classifier, XGBoost, LightGBM. However, AdaBoost model exhibits high values for recall, precision, F1-score, Kappa, and MCC, indicating strong overall performance. Therefore, by evaluating the highest value of these indices the best prediction model, AdaBoost, was selected. Through finalization and tuning, the AdaBoost model was further refined. Visualization methods including confusion matrices, AUC plots, and feature importance analysis were performed98. Additionally, Fig. 2 displays the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the AdaBoost model. The ROC plot (Fig. 2) shows the true positive rate (y-axis) and the false positive rate (x-axis) for each compound’s threshold between 0 and 1. Further, the ROC curve of each model was generated, and it is given in Fig. 2. Here, all curves have an AUC of 1.00, indicating that the classifier is perfectly distinguishing between the two classes. The above data undoubtedly explains the significant efficiency of each model.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the ML. Here, The ROC plot illustrates the true positive rate (y-axis) and the false positive rate (x-axis) of each compound’s threshold between 0 and 1 for AdaBoost model. Here, ROC of class 0, AUC = 1.00, this curve represents the performance of the classifier for class 0. The AUC (Area Under the Curve) is 1.00, indicating perfect classification for this class. ROC of class 1, AUC = 1.00, this curve shows perfect classification for class 1. Micro-average ROC curve, AUC = 1.00, this curve is the average of the ROC curves for each class, weighted by the number of samples in each class. An AUC of 1.00 indicates perfect overall classification. Macro-average ROC curve, AUC = 1.00, this curve is the average of the ROC curves for each class, without considering the number of samples in each class. Again, an AUC of 1.00 indicates perfect overall classification.

The probability scores for positive and negative class predictions were visualized using a scatter plot to illustrate the model’s classification performance (Supplementary Fig. 2). The plot shows high accuracy, with most predictions aligning with the true labels, indicated by a horizontal line at the top. This suggests strong model performance and high confidence in both positive and negative class predictions. However, based on the predicted probability scores for the positive class, we selected 20 compounds exhibiting the highest activity.

Pass prediction

The PASS activity of selected 20 active compounds (see Supplementary Table 1) from the machine learning approach was further evaluated using the Way2Drug server68. Out of 20 active compounds, ZINC03847075, ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577, and ZINC08952607 show microtubule formation inhibitors, beta-tubulin antagonistic, tubulin inhibitor, and anticancer, as well as cytostatic activity as shown in Table 2. Selected compounds are listed in Table 2, along with their PubChem IDs for further reference. This shows that the selected drug compounds have a tubulin binding activity and hence they were further considered for the ADME-T study.

ADME-T properties

The ADME and toxicity properties of ZINC03847075, ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577, and ZINC08952607 compounds were assessed using Swiss-ADME69 and pkCSM70 web server respectively, as shown in the Table 3. The ZINC03847075, ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577, and ZINC08952607 have molecular weight of 343.42, 487.54, 472.57, and 448.6, and iLogP value of 3.93, 4.48, 4.26, and 3.93 respectively Water solubility criteria such as Esol, Ali and Silico-IT shows that ZINC03847075 and ZINC08952577 compounds are poorly soluble, and ZINC08952607 and ZINC12889138 compounds are moderately soluble as shown in Table 3.

Lipinski rule, specifying < 5 hydrogen bond donors, < 10 hydrogen bond acceptors, showed only 1 violation for two compounds, which is acceptable. Bioavailability was predicted as 0.55, indicating neutrality. Only ZINC08952607 compound exhibited PAINS (Pan-Assay Interference Compounds) interference. Synthetic availability ranged between 1 (very easy) to 10 (difficult), with all compounds scoring < 6 as shown in Table 3. The toxicity analysis demonstrated that only ZINC03847075 compound displayed AMES mutagenesis, all the drug compounds show maximum tolerated dose (human) less than 0.5 and minnow toxicity < 0; and only ZINC08952607 compound showed hepatotoxicity. The selected compounds show appropriate pharmacokinetics activity which is helpful in further evaluations101.

Binding mode of αβIII tubulin isotype with ZINC compounds using Docking

Molecular docking was performed to identify the least binding energy conformation of ZINC03847075, ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577, and ZINC08952607 with αβIII tubulin isotype using AutoDock 4.2.372. The least binding energy conformation of ZINC03847075, ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577, and ZINC08952607 was found to be −8.52, −9.71, −10.80, and − 10.57 kcal/mol, respectively (Table 4). The analysis of αβIII-ZINC03847075 complex shows that the ZINC03847075 is stabilized by Leu273 (5.46Å), Leu361 (4.61Å), Ala231 (4.74Å), Leu361 (4.87Å), Val23 (5.43Å), Ala231 (4.60Å) and Pro358 (4.71Å) as shown in Fig. 3A; Table 4. Next, the analysis of αβIII-ZINC12889138 complex showed that ZINC12889138 is stabilized by only the non-bonded interactions of the alkyl and π-alkyl type with Ala23 (4.16 Å), Leu215 (4.26 Å), Leu284 (3.93 Å), Pro358 (4.97 Å), Leu361 (4.41 Å), Phe270 (4.92 Å), and Leu361 (5.42 Å) as shown in Fig. 3B; Table 4. The analysis of αβIII tubulin-ZINC08952577 complex shows that ZINC08952577 is stabilized by conventional hydrogen bonding interactions with Arg359 (3.16 Å), and Gly360 (2.85 Å), and CH type of bonding interaction with Thr274 (3.79 Å). Also, Phe270 and Leu361 form a π-donor and π-sigma type of bonding, Ala231 and Pro358 form alkyl, and Phe270, Leu361, and Leu284 form a π-alkyl type of interactions as shown in Fig. 3C; Table 4. Finally, the analysis of αβIII-ZINC08952607 complex showed that the ZINC08952607 is stabilized by only the CH type of interactions with Ala275 (3.37 Å) and Thr274 (3.47 Å) as shown in Fig. 3D; Table 4. While Leu215, Leu217, Ala231, Pro358, and Leu361 forms alkyl-type of interactions whereas Leu215, Leu217, Phe270, and Ala275, form a π-alkyl type of non-bonded interactions as listed in the Table 4.

Interaction of αβIII tubulin isotype with ZINC compounds. Here, (A) shows the αβIII tubulin docked with least energy ZINC03847075 (pink), ZINC12889138 (yellow), ZINC08952577 (green), and ZINC08952607 (magenta) compounds, (B) illustrates the binding mode of αβIII-ZINC03847075 and (C) its 2D interaction network. (D) Binding mode of αβIII-ZINC12889138 and (E) its 2D interaction network, (F) shows the binding mode of αβIII-ZINC08952577 and (G) 2D interaction work at binding pocket, and (H) shows the binding mode of αβIII-ZINC08952607 and (I) show its 2D interaction network. The 3D images in panels A-H were generated using PyMoL v2.5 (https://www.pymol.org/)42, while the 2D interaction network images in panels C-I was created using BIOVIA Discovery Studio v202473.

The analysis docking complexes revealed that only the non-bonded type of interactions stabilizes the αβIII-ZINC12889138 and αβIII-ZINC03847075 complexes. While, the αβIII-ZINC08952577 complex is stabilized by both the type of interactions such as bonded and non-bonded interactions. Similarly, the αβIII-ZINC08952607 complex is stabilized by the CH and non-bonded interactions as shown in Fig. 3; Table 4. Hence, to refine the binding mode and interaction, molecular dynamics simulation was employed and discussed below.

Molecular dynamic simulation

To investigate the refined mode of interaction, stability and affinity of αβIII tubulin isotype with natural drug compounds, MD simulations were performed using Gromacs2021.574. The least binding energy docked complex of αβIII-ZINC03847075, αβIII-ZINC12889138, αβIII-ZINC08952577, and αβIII-ZINC08952607 were used as a starting conformation for MD simulations (Fig, 3).

The stability of the MD simulation trajectories was examined by calculating the root mean square deviations (RMSD) of the Cα backbone atoms of αβIII tubulin isotype. RMSD plot revealed that all αβIII tubulin-drug complexes reached equilibrium after 200ns and remained stable, with fluctuations between 0.20 ± 0.40 nm as shown in Fig. 4A and structural dynamics of all the complexes are shown in Supplementary Movie 1–5. Furthermore, RMSD plot reveals that αβIII-ZINC12889138 complex has less RMSD fluctuations (below 0.3 nm) and is found to be highly stable compared to αβIII tubulin and αβIII tubulin-drug complexes as shown in Fig. 4A. Additionally, RMSD of the drug compounds were plotted to visualize its conformational changes in bound state over time (Supplementary Fig. 3). All drug compounds exhibited deviation patterns, with ZINC12889138 and ZINC03847075 showing more stable fluctuations compared to the others, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3. Additionally, the RMSD analysis revealed that ZINC12889138 and ZINC03847075 maintained lower fluctuations (below 0.3 nm), reflecting more stable binding throughout the simulation. In contrast, ZINC08952577 and ZINC08952607 showed persistent deviations, indicating relatively unstable interactions.

Moreover, to understand the impact of drug on the protein conformation, root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) of backbone Cα atoms were calculated. Regions with higher RMSF values correspond to greater flexibility, whereas lower RMSF values indicate more rigid or stable regions. As shown in Fig. 4B, regions in proximity to the Taxol binding site-specifically the M-loop (residues 272–287) and the H6-H7 loop (residues 210–240)-exhibit notable changes in dynamics. The RMSF analysis indicates that the M-loop becomes increasingly flexible upon drug binding to βIII tubulin. Similarly, the H6-H7 loop also showed enhanced dynamic behaviour. In addition to these, other regions such as the T5 loop (residues 170–180) and a segment of helix H11 (residues 405–426) display a significant increase in flexibility. The region comprises the H6 helix, T7 loop, H7 helix, S7 sheet, and M-loop, which collectively play a key role in accommodating drug compounds at the Taxol binding site (Supplementary Movie 1–5). The analysis of RMSF plot revealed that βIII-ZINC12889138 complex show lower RMSF value (specifically in the region; 225–375 amino acid) as compared to other βIII and drug complexes. Moreover, ZINC12889138 and ZINC08952577 compound has been found to be stable at the ‘Taxol site’ of βIII tubulin and showing the significant interactions with the M-loop (Supplementary Movie 3–4), compared to ZINC03847075 and ZINC08952607 (Supplementary Movies 2 & 5). Hence, to further understand the effect of drug on the protein’s structural stability and conformation the radius of gyration (Rg) and solvent accessible surface area (SASA) were calculated (Fig. 4C and D).

MD simulation analysis of the αβIII tubulin and drug complexes. Here, αβ-tubulin without drug is depicted in black, while αβIII-ZINC03847075 is depicted in red, αβIII-ZINC12889138 in green, αβIII-tubulin with ZINC08952577 in blue and αβIII-ZINC08952607 in orange. Panel (A) illustrates the RMSD plot of backbone Cα atoms of αβIII tubulin for 500ns; all the systems reached their equilibrium after 200ns time steps. Panel (B) displays the RMSF plot of the Cα backbone atoms of βIII tubulin. Panels (C) and (D) provide insights into protein conformational state through the assessment of radius of gyration (Rg) and solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) of αβIII tubulin heterodimer, respectively.

Radius of gyration (Rg) value has been utilized to get insight into the stability of a system by indicating the degree of compactness of a protein. Rg plot analysis revealed that αβIII-ZINC12889138 and αβIII-ZINC08952577 complex has less Rg value and more compact structure compared to αβIII-tubulin, αβIII-ZINC03847075 and αβIII-ZINC08952607 complexes as shown in Fig. 4C. Similarly, αβIII-ZINC12889138 (~ 300–325 nm2 and αβIII-ZINC08952577 (~ 300–340 nm2 complexes had a decrease in surface area as shown in Fig. 4D, while αβIII and αβIII with other drug complexes showed higher SASA value (Fig. 4D).

Overall, MD analysis revealed that the ZINC12889138 and ZINC08952577 have profound effect on the αβIII tubulin heterodimer as compared to other drug compounds. Furthermore, to explore effect of drugs on αβIII tubulin heterodimers, principal component analysis (PCA), free energy landscape (FEL) and binding energy calculations were performed and are discussed in the below sections.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

PCA is an important method to find the total combined movements of the Cα atoms in a protein, which are represented by the Eigen Vectors (EV) s of the covariance matrix. In this study, PCA was performed using the Cartesian coordinates of the 500 ns MD simulation trajectory to assess the conformational dynamics of the αβIII tubulin heterodimer and its complexes with selected compounds, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2), which represent the dominant motions, were extracted and plotted. The αβIII tubulin heterodimer complex with αβIII-ZINC03847075 exhibits wider diversity (PC1 range ~ −4 to 6 nm; PC2 ~ −3 to 4 nm) of conformations during the simulation. Among the complexes, the αβIII-ZINC08952577 (PC1 range ~ −4 to 6 nm; PC2 ~ −2 to 5.5 nm) and αβIII-ZINC08952607 (PC1 range ~ −4 to 6 nm; PC2 ~ −3 to 3 nm) also show wider distribution, indicating significant conformational flexibility in these complexes. While αβIII-ZINC12889138 complex (Fig. 5) exhibits the constricted clustering of data points along both PC1 and PC2 axes (PC1 range ~ −3 to 5 nm; PC2 ~ −3 to 2 nm), indicating limited structural fluctuations and enhanced rigidity. This suggests that the interaction with ZINC12889138 significantly restricts the dynamic movements of αβIII tubulin, likely favouring a more stable conformation. Overall, the PCA analysis revealed that ZINC12889138 induces notable structural stabilization of αβIII tubulin, as reflected by its minimal conformational variation in comparison to other ligand-bound forms. This rigidity may play a crucial role in its effectiveness as a potential inhibitory compound targeting the αβIII tubulin isotype.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of αβIII tubulin with drug complexes. Here, αβIII tubulin is represented in black, whereas αβIII-ZINC03847075 is depicted in red, αβIII-ZINC12889138 in green, αβIII-ZINC08952577 in blue and αβIII-ZINC08952607 in orange. The αβIII- ZINC12889138 complex showed lesser conformational diversity compared to all other complexes.

Free energy landscape

To explore the conformational dynamics and stability of αβIII tubulin in both its unbound form and when complexed with the ZINC03847075, ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577 and ZINC08952607, FELs and their corresponding contour maps were generated and analysed (Fig. 6). FELs allowed us to visualize the conformational state and identify potential energy barriers for transitions between the distinct structural configurations. Figure 6A and E illustrate the conformational ensembles of the various systems, where deep purple areas in the FEL indicate the most energetically favourable states (global minima) whereas other colors indicates the energetically unfavourable states (local minima). The unbound αβIII tubulin (Fig. 6A) demonstrates a broad distribution of conformations, requiring more extensive sampling to reach its lowest energy state, which lies within the range of 0 to 1.740 kJ/mol. In comparison, the αβIII-ZINC03847075 complex (Fig. 6B) reaches its energy minima between 0 and 1.820 kJ/mol, while αβIII-ZINC08952577 (Fig. 6D) and αβIII-ZINC08952607 (Fig. 6E) display minima in the range of 0 to 1.710 kJ/mol (Fig. 6D and E). These complexes exhibit a single dominant energy basin but show greater variability in their folding transitions. Notably, αβIII-ZINC12889138 complex (Fig. 6C) shows a narrower conformational distribution, with a global energy minimum between 0 and 1.680 kJ/mol, indicating enhanced structural stability throughout the simulation. The FEL profile of this complex suggests that it maintains a more stable conformation over time compared to the other ligand-bound forms and maintain the folding transition. Hence, to gain a deeper understanding of intermolecular interactions such as the bonded and non-bonded interactions between αβIII tubulin and the drug compounds, we further employed binding energy calculations using the MM-GBSA method.

Free energy landscape of αβIII tubulin and αβIII tubulin with drugs. Each FEL funnel of all the systems attains narrow edges (deep purple colour) over time which indicates the conformational stability of the tubulin with or without drug compounds. Along with the FEL funnel, contour map plot is also shown for each system. Here, (A) shows the FEL of αβIII tubulin, (B) FEL of αβIII- ZINC03847075 complex, (C) FEL of αβIII-ZINC12889138, (D) FEL of αβIII- ZINC08952577 complex, and (E) FEL of αβIII-ZINC08952607 complex.

Pair distribution functions (PDFs) analysis

Pair Distribution Function (PDF) plots representing the interaction profiles between αβIII-tubulin and the drug compounds following molecular dynamics simulations. The g(r) values indicate the probability of locating neighbouring atoms at a distance r (in Å) from a reference ligand atom, thereby reflecting the strength and nature of interactions within each complex. In the plot, αβIII-ZINC03847075 is shown in red, αβIII-ZINC12889138 in green, αβIII-ZINC08952577 in blue, and αβIII-ZINC08952607 in orange. Among the tested compounds, ZINC12889138 (green) demonstrates the most prominent and well-defined peak, suggesting strong, stable, and ordered interactions with αβIII-tubulin. Conversely, ZINC03847075 (red) displays the lowest peak, indicating the weakest interaction among the group.

Pair Distribution Functions (PDFs) provide a spatial distribution profile of drug molecules relative to a reference point during molecular dynamics simulations, offering crucial insights into molecular packing, interaction strength, and structural stability. As illustrated in Fig. 7, each drug compound exhibits a unique interaction profile. Notably, the PDF for the αβIII-ZINC12889138 complex shows the highest and most distinct first peak, centered around ~ 7 Å with a g(r) value of ~ 4.2 as shown in (Fig. 7). This sharp and prominent peak reflects a strong local ordering and a high likelihood of interaction at this specific distance, suggesting a robust and well-defined structural arrangement. The breadth of the peak also implies a degree of conformational flexibility in the interaction range. Beyond this point, the PDF oscillates before stabilizing near unity at larger distances, indicating persistent, long-range interactions (Fig. 7).

In contrast, the αβIII-ZINC08952577 and αβIII-ZINC08952607 complexes display first peaks around ~ 6 Å with peak g(r) values near ~ 3.3. Although less intense than ZINC12889138, these peaks still reflect moderate interaction strengths (Fig. 7). The αβIII-ZINC03847075 complex shows the weakest interaction, with a broad and relatively low-intensity first peak around ~ 6 Å and a peak height of approximately ~ 5. This indicates a lower probability of interaction and weaker structural ordering compared to the other systems. Overall, among the compounds studied, ZINC12889138 exhibits the strongest and most stable interactions with αβIII tubulin, while ZINC03847075 demonstrates the weakest, as supported by its low and diffuse PDF profile (Fig. 7).

Binding energy calculations

The binding energy calculations were performed using the MM/GBSA approach through gmx_mmpbsa tool90 to quantitatively clarify the energetics of the binding of αβIII tubulin with ZINC03847075, ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577 and ZINC08952607. The estimated binding energies (ΔEbind) of αβIII tubulin with ZINC03847075, ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577, and ZINC08952607 was found to be −0.02, −44.88, −29.62, −28.38 kcal/mol, respectively (Table 5). Among the analyzed complexes, αβIII tubulin exhibited the strongest binding affinity with the ZINC12889138 compound, while the lowest binding affinity was observed with ZINC03847075. (Table 5). The binding affinity of the αβIII tubulin towards the selected compounds followed a descending order: ZINC12889138 > ZINC08952577 > ZINC08952607 > ZINC03847075. Furthermore, In the αβIII- ZINC12889138, the van der Waals energy makes highest energy contribution, while in case of αβIII-ZINC08952577 both electrostatic and van der Waals make a contribution in the binding as compared to other complexes (Table 5).

The solvation energy (ΔE_sol) plays a significant role in ligand binding by offsetting the gas-phase binding energy (ΔE_gas) to varying extents. For αβIII-ZINC03847075, a significant reduction in the van der Waals interaction (−0.03 kcal/mol), a high ΔE_sol value (143.28 kcal/mol) which reduces the strong gas-phase interaction, resulted in less binding energy (ΔE_bind = −0.02 kcal/mol) while maintaining stability. In the case of αβIII-ZINC12889138, minimal solvation effects (ΔE_sol = 7.48 kcal/mol) allow the gas-phase interactions to dominate, yielding a stronger binding energy (ΔE_bind = −44.88 kcal/mol) indicating hydrophobic interactions. For αβIII-ZINC08952577, ΔE_sol (20.70 kcal/mol) partially offsets gas-phase energy, leading to balanced and moderate binding energy (ΔE_bind = −29.62 kcal/mol). In αβIII-ZINC08952607, substantial solvation effects (ΔE_sol = 321.15 kcal/mol) nearly neutralize gas-phase interactions, resulting in a moderate binding energy (ΔE_bind = −28.38 kcal/mol) and adaptability within the solvent-protein environment. The net binding free energy, which is decided by the competition of Egas and Esol, is lowest for αβIII-ZINC12889138 and αβIII-ZINC08952577 as shown in Table 5. As a result, the binding free energy calculation confirms the findings of MD simulation investigations indicating that the ZINC12889138 compound has highest binding affinity with αβIII-tubulin isotype compared to other drug compounds.

The per-residue energy decomposition analysis highlights the key binding site residues involved in stabilizing the interaction between αβIII tubulin and various drug candidates. In the αβIII tubulin–ZINC03847075 complex (Fig. 8A), Gly360 and Thr274 emerge as significant contributors to ligand binding, indicating their active role in the interaction. For the αβIII tubulin–ZINC12889138 complex (Fig. 8B), residues such as Leu228, Thr232, Phe270, and Leu273 show the highest energy contributions. Additionally, Leu215, His227, Ala231, Met300, and Leu361 also participate in stabilizing the complex, reinforcing the involvement of a broader binding interface within the αβIII tubulin isotype. In the αβIII tubulin–ZINC08952577 complex (Fig. 8C), prominent energy contributions are observed from Phe270, Pro272, Thr274, Arg276, and Leu361, along with Ala231 and His227, suggesting a strong network of interactions with the ligand. The αβIII tubulin–ZINC08952607 complex (Fig. 8D) features key contributions from residues Val23, Asp26, Ala231, Phe270, Arg359, Gly360, and Leu361, indicating their role in initiating and maintaining the binding process. Among all the complexes, the αβIII tubulin–ZINC12889138 complex (Fig. 8B) demonstrates the most diverse and energetically favorable set of interactions, involving multiple residues throughout the binding pocket. This extensive engagement likely accounts for its enhanced binding affinity compared to the other drug-tubulin complexes illustrated in Fig. 8A and C, and 8D.

Per-residue Energy Decomposition Analysis. Here, (A) shows the per residue energy decomposition of αβIII-tubulin with ZINC03847075, (B) per residue energy decomposition of αβIII-tubulin with ZINC12889138, (C) per residue energy decomposition of αβIII-tubulin with ZINC08952577, and (D) per residue energy decomposition of αβIII-tubulin with ZINC08952607.

Conclusion

This study identifies promising natural compounds as potential anticancer agents targeting the multidrug-resistant human αβIII tubulin isotype, which play critical role in tumor progression and drug resistance. Through an integrated approach of virtual screening, machine learning, and molecular docking, ZINC03847075, ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577, and ZINC08952607 compounds were identified based on their higher binding affinities to the ‘Taxol site’ of the βIII tubulin and favourable ADME-T and anti-tubulin properties. Molecular dynamics simulations further revealed that ZINC12889138, ZINC08952577, and ZINC08952607 significantly affects the stability of the αβIII tubulin heterodimer. Moreover, ZINC12889138 demonstrating the highest binding affinity, suggesting its superior inhibitory potential compared to other compounds. While these computational predictions underscore the therapeutic potential of these compounds, further experimental validation is crucial to confirm their efficacy and safety. This study lays the groundwork for innovative anticancer therapies targeting carcinomas that overexpress βIII tubulin isotype, offering a new direction in overcoming multidrug resistance in cancer treatment.

Data availability

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and it’s Supporting Information.

References

Wordeman, L. & Vicente, J. J. Microtubule targeting agents in disease: Classic drugs, novel roles. Cancers at (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13225650

Cao, Y. N. et al. Recent advances in microtubule-stabilizing agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 143, 806–828 (2018).

Prassanawar, S. S. & Panda, D. Tubulin heterogeneity regulates functions and dynamics of microtubules and plays a role in the development of drug resistance in cancer. Biochem. J. 476, 1359–1376 (2019).

Gao, M. et al. Combretastatin-A4 phosphate improves the distribution and antitumor efficacy of albumin-bound Paclitaxel in W256 breast carcinoma model. Oncotarget 7, 58133–58141 (2016).

Matthew, S. et al. Gatorbulin-1, a distinct cyclodepsipeptide chemotype, targets a seventh tubulin pharmacological site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, (2021).

Prota, A. E. et al. Structural basis of microtubule stabilization by Laulimalide and Peloruside A. Angew Chemie - Int. Ed. 53, 1621–1625 (2014).

Nussbaumer, S., Bonnabry, P., Veuthey, J. L. & Fleury-Souverain Analysis of anticancer drugs: A review. Talanta 85, 2265–2289 (2011).

Van Vuuren, R. J., Visagie, M. H., Theron, A. E. & Joubert, A. M. Antimitotic drugs in the treatment of cancer. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology vol. 76 1101–1112 at (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-015-2903-8

Weaver, B. A. How taxol/paclitaxel kills cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 25, 2677–2681 (2014).

Barbuti, A. & Chen, Z. S. Paclitaxel through the ages of anticancer therapy: exploring its role in chemoresistance and radiation therapy. Cancers (Basel). 7, 2360–2371 (2015).

Kavallaris, M. et al. Taxol-resistant epithelial ovarian tumors are associated with altered expression of specific beta-tubulin isotypes. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 1282–1293 (1997).

Galmarini, C. M. et al. Class III β-Tubulin isotype predicts response in advanced breast cancer patients randomly treated either with Single-Agent doxorubicin or docetaxel. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 4511–4516 (2008).

McCarroll, J. A., Gan, P. P., Liu, M. & Kavallaris, M. βIII-Tubulin is a multifunctional protein involved in drug sensitivity and tumorigenesis in Non–Small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 70, 4995–5003 (2010).

De Donato, M. et al. Class III β-tubulin and the cytoskeletal gateway for drug resistance in ovarian cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 227, 1034–1041 (2012).

Mozzetti, S. et al. Class III β-Tubulin overexpression is a prominent mechanism of Paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 298–305 (2005).

Gan, P. P., Pasquier, E. & Kavallaris, M. Class III β-Tubulin mediates sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs in Non–Small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 9356–9363 (2007).

Kavallaris, M., Burkhart, C. A. & Horwitz, S. B. Antisense oligonucleotides to class III β-tubulin sensitize drug-resistant cells to taxol. Br. J. Cancer. 80, 1020–1025 (1999).

Ling, K. S. et al. Mechanisms involved in chemoresistance in ovarian cancer. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 44, 209–217 (2005).

Perez, E. A. Microtubule inhibitors: differentiating tubulin-inhibiting agents based on mechanisms of action, clinical activity, and resistance. Mol. Cancer Ther. 8, 2086–2095 (2009).

Sève, P., Reiman, T. & Dumontet, C. The role of βIII tubulin in predicting chemoresistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 67, 136–143 (2010).

Tommasi, S. et al. Cytoskeleton and Paclitaxel sensitivity in breast cancer: the role of β-tubulins. Int. J. Cancer. 120, 2078–2085 (2007).

Mariani, M. et al. Gender influences the class III and V β-Tubulin ability to predict poor outcome in colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 2964–2975 (2012).

Sève, P. et al. Class III beta-tubulin expression in tumor cells predicts response and outcome in patients with non-small cell lung cancer receiving Paclitaxel. Mol. Cancer Ther. 4, 2001–2007 (2005).

Fitzgerald, D. P. et al. TPI-287, a new taxane family member, reduces the brain metastatic colonization of breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 11, 1959–1967 (2012).

Seidman, A. D. et al. Activity of tesetaxel, an oral taxane, given as a single-agent in patients (Pts) with HER2-, hormone receptor + (HR+) locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC) in a phase 2 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 1042–1042 (2018).

Chen, C. H. et al. Protopine, a novel microtubule-stabilizing agent, causes mitotic arrest and apoptotic cell death in human hormone-refractory prostate cancer cell lines. Cancer Lett. 315, 1–11 (2012).

Asami, Y. et al. Protuboxepin A, a marine fungal metabolite, inducing metaphase arrest and chromosomal misalignment in tumor cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20, 3799–3806 (2012).

Mukhtar, E., Adhami, V. M., Sechi, M. & Mukhtar, H. Dietary flavonoid Fisetin binds to β-tubulin and disrupts microtubule dynamics in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 367, 173–183 (2015).

Rai, K., Kumbhar, B. V., Panda, D. & Kunwar, A. Computational study of interactions of anti-cancer drug eribulin with human tubulin isotypes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 16694–16700 (2022).

Kumbhar, B. V. & Bhandare, V. V. Exploring the interaction of Peloruside-A with drug resistant αβII and αβIII tubulin isotypes in human ovarian carcinoma using a molecular modeling approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 39, 1990–2002 (2021).

Kumbhar, B. V., Panda, D. & Kunwar, A. Interaction of microtubule depolymerizing agent Indanocine with different human αβ tubulin isotypes. PLoS One 13(3), e0194934 (2018).

Kumbhar, B. V., Borogaon, A., Panda, D. & Kunwar, A. Exploring the origin of differential binding affinities of human tubulin isotypes αβII, αβIII and αβIV for DAMA-colchicine using homology modelling, molecular Docking and molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS One. 11, e0156048 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. Discovery of novel tubulin inhibitors targeting taxanes site by virtual screening, molecular dynamic simulation, and biological evaluation. J. Cell. Biochem. 122, 1609–1624 (2021).

Sun, L., Veith, J. M., Pera, P., Bernacki, R. J. & Ojima, I. Design and synthesis of de Novo cytotoxic alkaloids by mimicking the bioactive conformation of Paclitaxel. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18, 7101–7112 (2010).

Yadav, M., Dhagat, S. & Eswari, J. S. Structure based drug design and molecular Docking studies of anticancer molecules paclitaxel, Etoposide and Topotecan using novel ligands. Curr. Drug Discov Technol. 17, 183–190 (2020).

Gallego-Yerga, L. et al. Application of ensemble pharmacophore-based virtual screening to the discovery of novel antimitotic tubulin inhibitors. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 4360–4372 (2021).

Zúñiga-Bustos, M. et al. Mechanism-Based rational discovery and In vitro evaluation of novel microtubule stabilizing agents with Non-Taxol-Competitive activity. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 3204–3213 (2020).

Singh, R., Bhardwaj, V. K. & Purohit, R. Inhibition of nonstructural protein 15 of SARS-CoV‐2 by golden spice: A computational insight. Cell. Biochem. Funct. 40, 926–934 (2022).

Singh, R., Bhardwaj, V. K., Sharma, J., Das, P. & Purohit, R. Identification of selective cyclin-dependent kinase 2 inhibitor from the library of pyrrolone-fused benzosuberene compounds: an in Silico exploration. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 40, 7693–7701 (2022).

Kalsi, N., Gopalakrishnan, C., Rajendran, V. & Purohit, R. Biophysical aspect of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and role of oncogenic mutants (E542K & E545K). J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2015.1127774 (2016).

Fiser, A. & Šali, A. MODELLER: Generation and Refinement of Homology-Based Protein Structure Models. Methods in Enzymology 374 461–491 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74020-8

DeLano, W. L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.1. Schrödinger LLC http://www.pymol.org (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2014.17

Laskowski, R. A. et al. Structural summaries of PDB entries. Protein Sci. 27, 129–134 (2018).

Irwin, J. J. & Shoichet, B. K. ZINC - A free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. J. Chem. Inf. Model. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci049714+ (2005).

O’Boyle, N. M. et al. Open babel: an open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform. 3, 33 (2011).

Trott, O., Olson, A. J., AutoDock & Vina Improving the speed and accuracy of Docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 (2010).

Mohammad, T., Mathur, Y., Hassan, M. I. & InstaDock A single-click graphical user interface for molecular docking-based virtual high-throughput screening. Brief. Bioinform. 22, 1–8 (2021).

Dara, S., Dhamercherla, S., Jadav, S. S., Babu, C. M. & Ahsan, M. J. Machine learning in drug discovery: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 55, 1947–1999 (2022).

Vatansever, S. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning-aided drug discovery in central nervous system diseases: State‐of‐the‐arts and future directions. Med. Res. Rev. 41, 1427–1473 (2021).

Ghislat, G., Rahman, T. & Ballester, P. J. Recent progress on the prospective application of machine learning to structure-based virtual screening. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 65, 28–34 (2021).

Kadioglu, O., Saeed, M., Greten, H. J. & Efferth, T. Identification of novel compounds against three targets of SARS CoV-2 coronavirus by combined virtual screening and supervised machine learning. Comput. Biol. Med. 133, 104359 (2021).

Mysinger, M. M., Carchia, M., Irwin, J. J. & Shoichet, B. K. Directory of useful decoys, enhanced (DUD-E): better ligands and decoys for better benchmarking. J. Med. Chem. 55, 6582–6594 (2012).

Chen, L. et al. Hidden bias in the DUD-E dataset leads to misleading performance of deep learning in structure-based virtual screening. PLoS One. 14, e0220113 (2019).

Yap, C. W. PaDEL-descriptor: an open source software to calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1466–1474 (2011).

Ding, Y., Zhu, H., Chen, R. & Li, R. An efficient adaboost algorithm with the multiple thresholds classification. Appl. Sci. 12, 5872 (2022).

Stoltzfus, J. C. & Logistic Regression A brief primer. Acad. Emerg. Med. 18, 1099–1104 (2011).

Quinlan, J. R. Induction of decision trees. Mach. Learn. 1, 81–106 (1986).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Qu, L. & Pei, Y. A Comprehensive Review on Discriminant Analysis for Addressing Challenges of Class-Level Limitations, Small Sample Size, and Robustness. Processes 12, 1382 (2024).

Pagliaro, A. Forecasting significant stock market price changes using machine learning: extra trees classifier leads. Electronics 12, 4551 (2023).

Uddin, S., Haque, I., Lu, H., Moni, M. A. & Gide, E. Comparative performance analysis of K-nearest neighbour (KNN) algorithm and its different variants for disease prediction. Sci. Rep. 12, 6256 (2022).

Yang, Z. et al. A new Three-Way incremental Naive Bayes classifier. Electronics 12, 1730 (2023).

Qin, Y. A review of quadratic discriminant analysis for high-dimensional data. WIREs Comput. Stat 10(4), e1434 (2018).

Pan, J., Liu, Y. & Zhang, W. Detection of Dummy Trajectories Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Secur. Commun. Networks 1–12 (2019). (2019).

Cristianini, N. & Ricci, E. Support vector machines. In Encyclopedia of Algorithms 928–932 (Springer US, 2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30162-4_415.

Peng, J., Jury, E. C., Dönnes, P. & Ciurtin, C. Machine learning techniques for personalised medicine approaches in Immune-Mediated chronic inflammatory diseases: applications and challenges. Front Pharmacol 12, 1–18 (2021).

Lagunin, A., Stepanchikova, A., Filimonov, D. & Poroikov, V. PASS: prediction of activity spectra for biologically active substances. Bioinformatics 16, 747–748 (2000).

Druzhilovskiy, D. S. et al. Computational platform Way2Drug: from the prediction of biological activity to drug repurposing. Russ Chem. Bull. 66, 1832–1841 (2017).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7, 42717 (2017).

Pires, D. E. V., Blundell, T. L. & Ascher, D. B. PkCSM: predicting Small-Molecule Pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using Graph-Based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 58, 4066–4072 (2015).

Abdul-Hammed, M. et al. Virtual screening, ADMET profiling, PASS prediction, and bioactivity studies of potential inhibitory roles of alkaloids, phytosterols, and flavonoids against COVID-19 main protease (M pro). Nat. Prod. Res. 36, 3110–3116 (2022).

Morris, G. M. et al. Software news and updates AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated Docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791 (2009).

Abdel-Hamid, M. & McCluskey, A. In Silico docking, molecular dynamics and binding energy insights into the Bolinaquinone-Clathrin terminal domain binding site. Molecules 19, 6609–6622 (2014).

Van Der Spoel, D. et al. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. Journal of Computational Chemistry vol. 26 1701–1718 at (2005). https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20291

Meagher, K. L., Redman, L. T. & Carlson, H. A. Development of polyphosphate parameters for use with the AMBER force field. J. Comput. Chem. 24, 1016–1025 (2003).

Allnér, O., Nilsson, L. & Villa, A. Magnesium ion-water coordination and exchange in biomolecular simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 1493–1502 (2012).

Swails, J. et al. at https://github.com/ParmEd/ParmEd

Patil, A. F. et al. Investigating the novel acetonitrile derivatives as potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor using molecular modeling approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 41, 3943–3955 (2023).

Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J Chem. Phys 126, 1–8 (2007).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method polymorphic transitions in single crystals : A new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 7182–7190 (1981).

Hess, B., Bekker, H., Berendsen, H. J. C. & Fraaije, J. G. E. M. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1463–1472 (1997).

Darden, T., York, D. & Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089 (1993)

Turner, P. X. M. G. R. A. C. E. Version 5.1. 19. Cent. Coast. Land-Margin Res. Oregon Grad. Inst. Sci. Technol. Beavert. (2005).

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A. & Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Kitao, A. Principal component analysis and related methods for investigating the dynamics of biological macromolecules. J 5, 298–317 (2022).

Zúñiga, M. A. et al. Modulation of lateral and longitudinal interdimeric interactions in microtubule models by Laulimalide and Peloruside A association: A molecular modeling approach on the mechanism of microtubule stabilizing agents. Chem. Biology Drug Des. https://doi.org/10.1111/cbdd.13168 (2018).

Abraham, M. J. et al. High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX https://doi.org/10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001 (2015). Gromacs.

Anadebe, C. Surface interaction and Inhibition mechanism prediction of aciclovir molecule on Fe (110) using computational model based on DFT, RDF and MD simulation. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1238, 114702 (2024).

Mary, Y. S. et al. Concentration and solvent dependent SERS, DFT, MD simulations and molecular Docking studies of a Thioxothiazolidine derivative with antimicrobial properties. J. Mol. Liq. 329, 115582 (2021).

Akkus, E., Tayfuroglu, O., Yildiz, M. & Kocak, A. Accurate binding free energy method from End-State MD simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 4095–4106 (2022).

Miller, B. R. et al. MMPBSA.py: an efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 3314–3321 (2012).

Webb, B. & Sali, A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER. Methods Mol. Biol. 426, 39–54 (2017).

Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 (1993).

Li, Q. & Shah, S. Structure-Based virtual screening. in 111–124 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6783-4_5

Eberhardt, J., Santos-Martins, D., Tillack, A. F. & Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new Docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 3891–3898 (2021).

Islam, M. A. et al. Identification of potential cytochrome P450 3A5 inhibitors: an extensive virtual screening through molecular docking, negative Image-Based screening, machine learning and molecular dynamics simulation studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 9374 (2022).

Moez Ali, C. T. & PyCaret An open source, low-code machine learning library in Python. Version 2.3.5. (2021).

Duan, M. et al. Explainable machine learning models for predicting 30-day readmission in pediatric pulmonary hypertension: A multicenter, retrospective study. Front Cardiovasc. Med 9, 1–12 (2022).

Liu, J., Xu, L., Zhu, E., Han, C. & Ai, Z. Prediction of acute kidney injury in patients with femoral neck fracture utilizing machine learning. Front Surg 9, 1–10 (2022).

Zuo, D. et al. Machine learning-based models for the prediction of breast cancer recurrence risk. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 23, 276 (2023).

Pandey, R. K., Kumbhar, B. V., Sundar, S., Kunwar, A. & Prajapati, V. K. Structure-based virtual screening, molecular docking, ADMET and molecular simulations to develop Benzoxaborole analogs as potential inhibitor against Leishmania donovani trypanothione reductase. J. Recept Signal. Transduct. 37, 60–70 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Pruthanka Patil is thankful to University Grant Commission (UGC), New Delhi for Savitribai Jyotirao Phule single girl child fellowship for doctoral study. Bajarang Kumbhar is thankful to ICMR, New Delhi for extramural small grant F.NO. EMDR/SG/15/2024-01-03727. We are thankful to the Biorender tool for providing the imaging platform.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PP: Methodology, Analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing-original draft, review and editing, BK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Data Curation, Analysis, Validation, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.The data underlying this study are available in the published article and it’s Supporting Information.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary Material 2

Supplementary Material 3

Supplementary Material 4

Supplementary Material 5

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Patil, P.A., Kumbhar, B.V. Structure based drug design and machine learning approaches for identifying natural inhibitors against the human αβIII tubulin isotype. Sci Rep 15, 32716 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17708-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17708-5