Abstract

An eco-friendly composite material was developed as a cost-effective and efficient adsorbent for removing Acid Blue 25 (AB25) dye from aqueous solutions. Despite extensive research on dye adsorbents, there remains a need for sustainable and high-performance materials. While chitosan and sodium alginate have shown promise individually, their composite with halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) is less explored. In this study, chitosan/sodium alginate (CSA) and chitosan/sodium alginate/halloysite nanotube (CSAH) composites were synthesized and evaluated for AB25 removal under varying conditions, including pH (3–11), contact time (2–120 min), initial dye concentrations (20–600 mg/L), and HNT content (5–30%). Characterization of the adsorbents was carried out using BET, zeta potential, FESEM, FTIR, EDX, and XRD analyses. CSAH adsorbents were prepared by incorporating different HNT ratios (5–30%) into CSA. At pH 3, CSA achieved 80% dye removal after 70 min, while CSAH with 10% HNT content (CSAH10) showed the best performance, removing 94% of dye within 30 min. Adsorption isotherms (Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, Redlich-Peterson, Toth) revealed that the Toth model best described the equilibrium behaviour. According to the Langmuir model, the maximum adsorption capacity of CSAH10 was 351 mg/g. Kinetic studies, including pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, intraparticle diffusion, and Elovich models, indicated that the adsorption process followed the pseudo-second-order model for both CSA and CSAH adsorbents. Regeneration tests showed a gradual decline in efficiency, with CSAH10 maintaining 58% removal after five cycles, down from 91% initially. Overall, the CSAH10 composite exhibited strong potential for practical AB25 dye removal, combining high efficiency, low cost, and relatively good reusability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, wastewater treatment with composite materials has attracted much attention1. Discharging toxic materials from various industries into water negatively affects water resources and the integrity of the ecosystem2. Textile wastewater is considered a polluting industry. In the textile industry, a large volume of water is used, so in this situation, large quantities of wastewater are generated at various stages3. In the environment, dyes cause many problems due to their great thermal and optical resistance, so they can maintain their state for a long time4. Industrial wastewater residues can contain a large volume of dye content. Ingredients in wastewater are classified as, neutral, direct, acidic, dispersive and metal complex5. In the textile industries, acid dyes account for more than 30% of used dyes, and about 15% of them can enter the wastewater of industries and the environment through various activities6. Acid Blue 25 (AB25) is a colorant commonly used in the textile industry and is a potential carcinogen because it can degrade into aromatic amines, which are known to induce DNA mutations. AB25 has the capability of degrading into harmful byproducts in an aquatic environment under different circumstances, such as elevated temperature, light exposure, and microbial activity, which enhances its potential to cause cancer. Exposure to these degradation products, especially from contaminated water bodies, has, over time, been proven to possess serious health hazards. Besides, the persistence of AB25 in aquatic systems is also an ecological concern, as the dye is bio-accumulative, enhancing risks to human health and wildlife. Hence, the efficient removal and degradation of AB25 from wastewater are of vital importance in reducing its carcinogenic risks and protecting environmental and public health7. The methods that are intended to be utilized for dye removal from wastewater are classified as physical, biological and chemical8. However, the biological and chemical methods have disadvantages such as the use of large amounts of chemicals, toxic sludge generation, high cost and incomplete dye removal9. The main technologies, with different processing efficiency, include advanced oxidation processes10, ion exchange11, bioremediation12, coagulation-flocculation13, activated sludge14, reverse osmosis15, membrane filtration16,17 and adsorption18. The various wastewater treatment technologies offer distinct advantages and limitations. Advanced oxidation processes are highly effective in degrading complex organic pollutants, however, they come with high operational costs due to energy and chemical requirements10. Ion exchange is efficient at selectively removing ions, though it necessitates frequent resin regeneration, leading to secondary waste issues11. Bioremediation is an environmentally friendly and cost-effective method, yet it is often slow and less effective for non-biodegradable contaminants12. Coagulation-flocculation can quickly remove suspended particles and color but generates large amounts of sludge requiring proper disposal13. The activated sludge process excels at eliminating organic matter but demands significant energy for aeration and a large space for operation14. Reverse osmosis produces high-quality water by removing a broad spectrum of contaminants, though it generates a concentrated brine that poses disposal challenges15. Similarly, membrane filtration is effective at removing fine particles and microorganisms but is hindered by membrane fouling, necessitating frequent maintenance19. Among available wastewater treatment techniques, adsorption is generally considered a cost-effective process with rapid effectiveness against a variety of contaminants, simple operation and design, lower generation of toxic byproducts and low initial cost20. Successful and complete adsorption of contaminants from water ensures their recovery, which is particularly important for nutrients in water21. In addition, it is worth mentioning that the regeneration of adsorbent in the adsorption process is becoming increasingly important for subsequent adsorption cycles, which would reduce operation costs22.

Chitosan is a natural polymer with the functional groups of hydroxyl (\(\:-\text{O}\text{H}\)) and amino (\(\:{-\text{N}\text{H}}_{2}\)), which is obtained from the hydrolysis of chitin under alkaline conditions23. The hydroxyl and amino groups also enable the modification of chitosan composites with definite functionality to alter physicochemical and biological properties24. The presence of these functional groups has a significant impact on the reactivity of chitosan and makes it illustrate excellent biological, physical and chemical properties25. Chitosan has a wide variety of degrees of deacetylation. It should be noted that the degree of deacetylation has a significant effect on physicochemical properties, reactivity, molecular weight, charge densities and charge distributions26. Composites of chitosan and other substances have demonstrated conformability, durability and adsorption capacity in acidic conditions27.

Alginate is a well-known member of the polysaccharide group which is obtained from brown algae. Due to its great characteristics such as non-toxicity, specific functional groups, biocompatibility and low cost, it is widely used in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and textile industries28. Alginate-based adsorbents are of great importance in wastewater treatment processes because of their biocompatible and biodegradable nature29. Alginate is water soluble and its aqueous solution is thick and viscous, and if there is a divalent cation, it generates hydrogels based on the complexion mechanism. The generation of hydrogel is also known as inotropic gelation. Owing to this characteristic; the alginate gel formation; chitosan, activated carbon and clays can be combined with alginate gel and used for the adsorption process30. The use of biobased hydrogels in water treatment has gained much attention due to their hydrophilic nature, good reusability and minimum chemical and biological sludge generation31. Alginate and chitosan generally can be used in composite materials including grafting polymerization networks and incorporation of metals and oxide metals nanocomposites to synthesize advanced biobased adsorbents32.

Halloysite is a nano-sized natural mineral with a layered and tubular structure. Each halloysite layer consists of tetrahedral (\(\:\text{S}\text{i}-\text{O}\)) and octahedral (\(\:\text{A}\text{l}-\text{O}\text{H}\)) sheets and one alumina octahedral sheet, which is identical to sheets in kaolinite structure33. However, interlayer spaces in the halloysite are separated by a layer of water molecules and halloysite mainly has higher water content compared to kaolinite34. Halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) have a rolling structure resulting from a misfit between \(\:\text{S}\text{i}-\text{O}\) and \(\:\text{A}\text{l}-\text{O}\) bonds35. These functional groups have distinctive charges and pH values. The HNTs have a slight negative charge on the outer surface with pH ≥ 1.5, while the inner surface of the lumen has a positive charge with pH ≤ 8.5, and due to this characteristic, each surface would be able to adsorb molecules selectively36. The HNTs have the chemical formula of \(\:{\text{A}\text{l}}_{2}{\text{S}\text{i}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{5}{\left(\text{O}\text{H}\right)}_{2}.\text{n}{\text{H}}_{2}\text{O}\), outer diameter in the range of 50 to 80 nm, lumen diameter in the range of 10 to 15 nm and length of 1 μm37. Halloysite has great advantages including biocompatibility, hydrophilicity, and good dispersibility compared to other nanoparticles. Additionally, HNTs as nano clay minerals, are low-cost, eco-friendly adsorbents with strong cation exchange capacity and surface reactivity, offering an effective alternative for removing various contaminants38.

Despite HNTs’ promising physicochemical properties, the integration of HNTs into chitosan/alginate composites for dye adsorption remains underexplored. Additionally, current research often lacks detailed mechanistic insights, such as the roles of electrostatic interactions and surface chemistry in adsorption, especially in advanced hybrid composites. These gaps highlight the need for innovative approaches to optimize dye removal technologies, particularly for specific dyes like AB25.

The primary objective of this study is the development and evaluation of a novel chitosan/sodium alginate/halloysite nanotube (CSAH) triple composite adsorbent, designed specifically for the effective removal of Acid Blue 25 (AB25) dye from aqueous solutions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the fabrication of a CSAH composite incorporating systematically varied halloysite nanotube (HNT) loadings to optimize performance. The integration of chitosan and alginate introduces abundant amino, carboxyl, and hydroxyl functional groups that facilitate strong electrostatic and hydrogen bonding interactions with the anionic dye molecules. The incorporation of HNTs not only enhances the structural stability of the composite, particularly under acidic conditions, but also increases the surface charge and introduces additional active sites for adsorption. Importantly, the optimization of the HNT mass ratio was found to significantly accelerate adsorption kinetics and boost dye removal efficiency, distinguishing this material from previously reported chitosan- or alginate-based adsorbents. This approach presents a synergistic combination of natural polymers and nanotubular clay for fast, efficient, and pH-tolerant dye adsorption, offering a promising and eco-friendly alternative for wastewater treatment applications. The efficiency of adsorption was investigated by batch experiments focusing on the effects of solution pH, contact time, and HNTs ratio. Accordingly, kinetic, isotherm, and regeneration analyses were done to fully understand the working of the adsorption mechanism and effectiveness of the adsorbents.

Materials and methods

Materials

Chitosan (CS, low molecular weight, viscosity 20–300 centipoises (cps) and degree of deacetylation ≥ 75%) and sodium alginate (SA) with viscosity of 4–12 cps were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Co. Halloysite nanotubes (HNTs, 0.5–2 μm long, 15–30 nm in diameter) were purchased from IMERYS Tableware Asia Ltd (New Zealand). The chemical analysis details of HNTs are listed in Table 1. Acid Blue 25 (AB25) a model organic pollutant in wastewater (chemical formula \(\:{\text{C}}_{20}{\text{H}}_{13}{\text{N}}_{2}\text{N}\text{a}{\text{O}}_{2}\text{S}\), molecular mass 416.3 g\(\:{\text{m}\text{o}\text{l}}^{-1}\)) was purchased from Alavan Sabet Company (Hamedan, Iran). The Chemical structure of AB25 is shown in supplementary data Fig. 1A. Acetic acid (glacial) 99.9%, sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and hydrochloric acid (HCl) were obtained from Merck Co.

Preparation of adsorbents

Briefly, to synthesize chitosan-sodium alginate composite (CSA), 0.5 g of chitosan powder was dissolved in 25 mL of 2 wt% acetic acid solution under magnetic stirring for 2 h at ambient temperature. Thereafter, 0.5 g of sodium alginate was added to the solution and mixed thoroughly for 12 h. Afterward, halloysite nanotubes were dispersed in the mixture at weight ratios of 5, 10, 15, 20 and 30% (mass ratio of HNT/CSA) with the aid of an ultrasonic bath for about 5 min, and then mixed for 20 h at room temperature. Eventually, the solutions of CSA-HNTs composite were poured into plates and cooled at -15 °C in a refrigerator overnight. Then, all composites were frozen in a freeze drier at -48 °C for 24 h under vacuum condition, and named CSAH5, CSAH10, CSAH15, CSAH20 and CSAH30. The flow diagram describing the adsorbent preparation is shown in Fig. 1.

Characterization methods

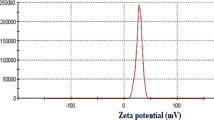

The Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra of the adsorbents were recorded using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet spectrometer (iS50, Netherlands). The crystalline structure was analyzed with an X-ray diffractometer (Philips X’PERT MPD, PW3040, Netherlands) over a 2θ range of 5–60°. Morphological studies were conducted using a Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM, TeScan MIRA3 model, Czech Republic). Textural properties, including the specific surface area and average pore diameter, were determined through nitrogen adsorption-desorption analysis using a gas adsorption analyzer (Micromeritics TriStar II, US). The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method provided data on the surface area, while the Barret–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method was used to analyze pore size distribution from adsorption isotherms. Elemental composition was assessed with Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis using the TeScan MIRA3 model (Czech Republic). Additionally, the zeta potential of the adsorbent was measured via electrophoretic light scattering device (HORIBA Scientific SZ-100, France).

Adsorption experiments

A batch-mode experiment was conducted to evaluate dye adsorption. For each test, 0.05 g of the adsorbent was dispersed in 25 mL of dye solution with varying initial dye concentrations (25–200 mg/L), pH levels (3–11), and contact times (1–120 min) under constant shaking at 300 rpm at room temperature (25–27 °C). The pH of the AB25 solution was adjusted using 0.1 mol/L HCl and 0.1 mol/L NaOH solutions. At predetermined intervals, the amount of adsorbed dye was quantified using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Hach, DR4000, US) by measuring absorbance at the maximum wavelength of 602 nm.

The removal efficiency of AB25 adsorption at any time can be calculated as follows:

The amount of AB25 adsorption capacity was calculated as follows:

where \(\:{\text{q}}_{\text{t}}\)(mg/g), C0 (mg/L) and Ct (mg/L) show the capacity of adsorbent at time t, the initial concentration of adsorbate and the concentration of adsorbate at time t, respectively. V (L) and m(g) indicate the volume of the dye solution and the mass of the adsorbent respectively18.

Results and discussion

Characterization analysis

Based on the chemical analysis presented in Table 1, the halloysite used in this study exhibited a specific surface area of approximately 20 m²/g. In comparison, previously reported values for halloysite range from 56 to 64 m²/g. The cation exchange capacity (CEC) of the halloysite was around 10 meq/100 g, whereas literature values have reported higher CECs, typically between 19.2 and 20 meq/100 g39. The functional groups of the synthesized materials were analyzed using FTIR spectroscopy, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. In Fig. 2(a), the broadband at 3427 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the overlapping stretching vibrations of the OH and NH groups40. The peak at 2875 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the symmetrical and asymmetrical \(\:\text{C}-\text{H}\) stretching vibrations in the chitosan matrix. Sharp peaks at 1654 cm⁻¹ and 1601 cm⁻¹ represent \(\:-\text{N}{\text{H}}_{2}\:\)bending and \(\:\text{C}=\text{O}\) stretching vibrations in the HCO matrix, respectively. Peaks at 1417 cm⁻¹ and 1381 cm⁻¹ are assigned to \(\:\text{C}-\text{O}\) and \(\:\text{C}-\text{N}\) stretching vibrations, while the bands at 1084 cm⁻¹ and 1158 cm⁻¹ indicate polysaccharide bonds related to \(\:\text{C}-\text{O}\) stretching vibrations41. For sodium alginate (SA), the FTIR spectrum shows a broad peak at 3423 cm⁻¹ due to \(\:\text{O}-\text{H}\) stretching vibrations, a peak at 2929 cm⁻¹ for \(\:-\text{C}{\text{H}}_{2}\) functional groups, and characteristic peaks at 1637 cm⁻¹ and 1421 cm⁻¹ corresponding to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of COO⁻ carboxylate groups. Additionally, a peak at 1026 cm⁻¹ indicates saccharide stretching within the SA framework42. In the FTIR spectrum of the chitosan-sodium alginate composite (CSA), the peak shifts to 3422 cm⁻¹ due to the interaction between CS and SA, where the positive ammonium groups in CS form electrostatic bonds with the carboxylate ions in SA, resulting in a polyelectrolyte complex43. Further, the stretching vibration of \(\:\text{C}=\text{O}\) shifts from 1654 cm⁻¹ to 1630 cm⁻¹, confirming CSA composite formation. Electrostatic interactions involving CaCl2 and tri-polyphosphate functional groups further enhance the connection between CS and SA44. The broad peak (at 3422–3427 cm⁻¹) observed in all three spectra (CS, SA and CSA) exhibits slight shifts and broadening in the CSA spectrum, indicating strong hydrogen bonding. Additionally, the CSA spectrum displays a merged and shifted peak at 1630 cm⁻¹ compared to the CS and SA spectra. This shift highlights the formation of ionic bonds between the COO⁻ groups of SA and the NH₃⁺ groups of CS. Similarly, the peak at 1097 cm⁻¹ in the CSA spectrum shows a slight shift from the individual value of 1084 cm⁻¹, confirming that structural blending impacts the polysaccharide backbone. Overall, the CSA composite retains the key characteristics of both polymers, while the observed shifts and overlaps validate the successful interaction and formation of a blended material with modified properties45. Figure 3(a) and (b) depict FTIR spectra of HNTs and CSAH10. For HNTs, characteristic peaks include 3549 cm⁻¹ (\(\:\text{O}-\text{H}\) stretching of water), 1652 cm⁻¹ (\(\:\text{O}-\text{H}\) deformation of water). Peaks at 3695 cm⁻¹ and 3623 cm⁻¹ correspond to hydroxyl (\(\:-\text{O}\text{H}\)) stretching vibrations from the \(\:{\text{A}\text{l}}_{2}-\text{O}\text{H}\) bond on the HNTs surface46. The bands at 1036 cm⁻¹ and 912 cm⁻¹ correspond to the stretching vibrations of Si–O–Si bonds and the bending vibrations of inner surface hydroxyl groups (Al–O–H), respectively. Additionally, the band at 537 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the deformation vibration of Al–O–Si bonds39. In the CSAH10 composite, the appearance of characteristic HNTs peaks at 3695 cm⁻¹ and 912 cm⁻¹, along with those from the CSA matrix, confirms the successful incorporation of HNTs into the CSA framework47. The characteristic peaks of HNTs at 3695, 3549, and 1036 cm⁻¹ are retained in the CSAH10 spectrum but show reduced intensity and slight shifts. This indicates the successful incorporation of HNTs into the composite, with interactions primarily involving hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions. In the HNTs spectrum, peaks at 912 cm⁻¹ (Al-OH bending) and 469 cm⁻¹ (Si-O bending) also exhibit reduced intensity, confirming the contribution of HNTs to the structural framework of the CSAH10 composite. The broad peak at 3422 cm⁻¹ in the CSAH10 spectrum is broader compared to the CSA composite, suggesting stronger hydrogen bonding due to the addition of HNTs. Furthermore, the COO⁻ stretching peaks (asymmetric at 1564 cm⁻¹ and symmetric at 1411 cm⁻¹) in CSAH10 are slightly shifted relative to the CSA spectrum, reflecting enhanced ionic interactions between alginate and HNTs in the presence of chitosan. The Si-O stretching peak at 1036 cm⁻¹, which is absent in CSA, appears prominently in CSAH10, confirming the incorporation of halloysite nanotubes48. Chitosan’s amide I and amide II peaks (1654 and 1601 cm⁻¹) and alginate’s COO⁻ peaks (1637 and 1421 cm⁻¹) are merged and shifted in CSAH10, indicating strong interactions among the components. Additionally, the new HNT-related peaks at 1036 cm⁻¹ and 912 cm⁻¹ in CSAH10 further confirm the presence of halloysite nanotubes within the composite45. Some characteristic peaks are summarized in Table 2.

The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm and BJH pore size distributions are provided in Fig. 4. The N2 adsorption-desorption curve indicates the mesoporous pore size of CSAH10 in the range of 2–50 nm. The isotherm (Fig. 4a) displays a type II with distinct type H3 hysteresis loop in the relative pressure (P/\(\:{\text{P}}_{0}\)) and this type of isotherm was a typical characteristic of mesoporous and macropores structures49. The BET surface area of the CSAH10 composite was measured to be 0.7791 m²/g, which is lower than the values reported for raw halloysite nanotubes (60 m²/g) and their chitosan-based composites (82 m²/g). It also falls below the surface areas documented for sodium alginate (21.1 m²/g) and sodium alginate–halloysite composites (2.9 m²/g). This reduction can be attributed to the formation of a compact biopolymer matrix composed of chitosan and alginate, which likely envelops the halloysite nanotubes and restricts access to their internal pores. In addition, the dense structure created by hydrogen bonding between the polymer chains and their relatively high molecular weights may further limit the availability of accessible surface area. Despite this modest BET surface area, the material retains a mesoporous architecture and is rich in functional groups—such as amino, hydroxyl, and carboxyl moieties—verified through FTIR and zeta potential analysis. The BJH pore size distribution results are shown in Fig. 4b and c, indicating that the average pore diameter of CSAH10 was calculated to be 15.96 nm, and the pore volume was determined as 0.00311 \(\:{\text{c}\text{m}}^{3}/\)g.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of chitosan (CS), sodium alginate (SA), the chitosan–sodium alginate composite (CSA), pure halloysite nanotubes (HNTs), and the CSAH10 composite are presented in Fig. 5. In Fig. 5(a), two sharp peaks observed at 2θ = 11.4° and 20.4° are attributed to the semi-crystalline structure of chitosan. This crystallinity arises from the regular arrangement of polymer chains stabilized by intermolecular hydrogen bonding, particularly involving –OH and –NH₂ functional groups50. In contrast, the XRD pattern of sodium alginate (Fig. 5(b)) displays broader peaks at 2θ = 19.4° and 31.8°, which are indicative of its predominantly amorphous nature due to the more irregular structure of alginate chains51. For the CSA composite, the XRD pattern shown in Fig. 5(c) exhibits a notable reduction in the intensity of the characteristic peaks associated with both CS and SA. This reduction is primarily due to the disruption of hydrogen bonding between chitosan chains upon blending with alginate, leading to a decrease in overall crystallinity52. However, the presence of peaks at 2θ = 11.9°, 19.1°, and 31.8° still confirms successful formation of the CSA composite, suggesting a semi-crystalline nature with reduced structural order compared to the individual components. The XRD pattern of pure halloysite nanotubes (Fig. 5(d)) displays well-defined peaks at 2θ = 11.9°, 19.9°, and 24.8°, consistent with the highly crystalline nature of HNTs as reported in literature46. These peaks confirm the ordered tubular structure of the mineral component. In Fig. 5(e), the CSAH10 composite exhibits distinct peaks at 2θ = 12.7°, 20.3°, and 24.9°, aligning with the crystalline peaks of HNTs and CS, while the presence of a peak at 2θ = 31.8° corresponds to SA. The presence of these peaks indicates that the CSAH10 composite retains partial crystallinity, derived primarily from the crystalline HNTs and the semi-crystalline regions of CS. Compared to the CSA composite, the incorporation of halloysite nanotubes enhances the overall crystallinity of the material. This partial crystalline structure in CSAH10 may contribute to improved mechanical stability and may influence dye adsorption by affecting porosity and surface characteristics53.

The FE-SEM images of HNTs are shown in Fig. 6(a). It reveals the tubular structure of HNTs. Also, the SEM image of CSA composite is shown in Fig. 6(b). The structure on the surface of the CSA composite is smooth because of the smooth surface of the pure sodium alginate and coating of composite surface with chitosan molecules54. The SEM image of CSAH10, the mass ratio of HNTs to CSA composite is 10%, is shown in Fig. 6(c). The structure on the surface of CSAH10 was revealed to be rougher in surface structure compared to the CSA composite. This is because of adding HNTs to the CSA composite structure. The SEM image of CSAH30, the mass ratio of HNTs to CSA composite is 30%, is shown in Fig. 6(d). The main difference between CSAH10 and CSAH30 is that the amount of halloysite nanotube in CSAH30 is greater than CSAH10, and this probably would not change the whole surface structure of CSAH regardless of the amount of HNTs. It can be observed from Fig. 6(d) that halloysite nanotubes are more visible than in Fig. 6(c). The Energy Dispersive spectroscopy micrograph and elemental mapping of CSA composite and CSAH10 are shown in Fig. 7(a, left side) and (b, right side). Figure 7(b) reveals the presence of halloysite nanotubes on the CSA composite, because the content of aluminum and silicon which are the main elements of HNTS, are more than CSA composite based on the report of element weight percentages. The elemental composition (mass ratio, wt%) of the CSA and CSAH10 samples based on EDS analysis is summarized as follows: For the CSA composite, the dominant elements were carbon (32.23%), oxygen (40.97%), nitrogen (5.42%), and sodium (21.28%). In contrast, the CSAH10 composite showed an increase in carbon (38.63%) and oxygen (43.52%), with additional signals for aluminum (3.86%) and silicon (4.14%), which are characteristic elements of halloysite nanotubes. The sodium content significantly decreased to 4.91% after HNT incorporation. These results confirm the successful integration of HNTs into the CSA matrix and support the observations made in the elemental mapping. It also shows that the HNTs are uniformly distributed over the surface of CSA composite and the interface between HNTs and CSA composite matrix is clear55.

The zeta potential of CSAH10 was measured 3 times in the pH values of 3, 4, 6 and 9, and is shown in supplementary data Fig. 2A. For the analysis, a 0.1 wt% aqueous suspension of CSAH10 was prepared and ultrasonicated for 10 min to ensure uniform dispersion prior to measurement. The results indicate that CSAH10 exhibits a positive zeta potential across the tested pH range, with the highest value observed at pH 3. As the pH increases, the zeta potential decreases steadily, indicating a reduction in surface charge. This trend can be attributed to the protonation and deprotonation of functional groups on the composite surface. At low pH, the amino groups (–NH₂) of chitosan are protonated to –NH₃⁺, and carboxyl and hydroxyl groups on alginate and halloysite surfaces may also be in their protonated forms. This leads to a strongly cationic surface, which enhances the electrostatic attraction between the adsorbent and anionic dye molecules like AB25. As the pH increases, these functional groups undergo deprotonation, diminishing the net positive surface charge. At pH 9, the zeta potential is significantly lower, reflecting a weaker electrostatic interaction potential under alkaline conditions56.

Effect of solution pH on the adsorption process

The pH of a solution is an important parameter in the adsorption mechanism and influences the efficiency of dye removal. The extent of AB25 dye removal is related to the solution’s initial pH and the nature of the adsorbent surface charge, which may be defined by its point of zero charge (pHpzc). Changes in pH may result in an increase or a decrease in the capacity for dye adsorption, depending on changes in the adsorbent’s surface charge. The pH value of the solution affects the magnitude of the electrostatic interactions between the adsorbent and the adsorbate, thereby markedly influencing the removal efficiency. The anionic nature of the AB25 dye molecules attracts them to the surface of the positively charged adsorbent, underlining the prime contribution of ionic interactions in the mechanism of adsorption57.

The effect of solution pH on the adsorption process was examined in the range of 3 to 11 by applying an adsorbent dosage of 2 g/L, initial concentration of 50 mg/L and at a constant temperature of 27 °C for about 2 h. The effect of pH value on the adsorption process for CSA and CSAH10 is shown in Fig. 8. As it shows, dye removal decreased in equilibrium condition at the end of the adsorption process with an increase in pH value. In acidic conditions, because of the formation of hydrogen bonds, the adsorption of AB25 molecules, as an anionic dye, is favorable for the positively charged surfaces of the adsorbent. Moreover, the NH₂ groups of chitosan are protonated to NH₃⁺, leading to strong electrostatic attraction between the positively charged adsorbent surface and the negatively charged dye molecules. As pH approaches neutrality, the degree of protonation of chitosan decreases, reducing electrostatic interactions. However, other interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces, still contribute to adsorption58. According to the zeta potential results, it can be interpreted that the adsorbent reveals cationic properties and shows a favorable tendency over the adsorption of anionic compounds. In Fig. 8(a), the maximum dye removal percentage of CSA is obtained 79.9, 72.4, 70.3, 60.3 and 51.8 for pH values of 3, 4, 6, 9 and 11 respectively. Also, In Fig. 8(b), the maximum dye removal percentage of CSAH10 is calculated as 93.8, 83.1, 78.5, 71.5 and 59.6 for pH values of 3, 4, 6, 9 and 11 respectively. At all pH values, CSAH10 consistently outperforms CSA, with a particularly notable improvement in acidic and neutral conditions. The maximum dye removal percentage for CSA and CSAH10 in pH value of 3 are obtained 79.9 and 93.8 respectively. Because, the incorporation of halloysite nanotubes introduces additional adsorption sites, including hydroxyl groups, which enhance the overall adsorption capacity. The tubular structure of HNTs may also provide more active sites and facilitate dye diffusion into the composite matrix45. With a pH value greater than 9.0, the percentage of AB25 dye removal shows a gradual decrease. This can be majorly attributed to a kind of competition between hydroxyl ions (OH⁻) and the anionic sulfonic groups of AB25 for the adsorption sites available. Additionally, the surface charge of the adsorbents becomes less positive or even negative due to the deprotonation of chitosan. The negatively charged adsorbent surface experiences electrostatic repulsion with the dye molecules, leading to reduced adsorption efficiency57. CSAH10 demonstrates better adsorption efficiency at pH 6 and 9 compared to CSA, suggesting that HNTs help stabilize adsorption performance across a wider pH range because the interactions between HNTs and dye molecules supplement the pH-dependent electrostatic interactions provided by chitosan and alginate45. The highest adsorption capacity was obtained at a highly acidic pH of 3 and decreased with the increase in pH. A similar result was obtained by Hanafiah et al.59. At reduced pH values, the high concentration of H⁺ ions in the solution protonates the carboxyl, hydroxyl, and amino functional groups on the adsorbents. This increases the degree of electrostatic attraction between the positively charged surface of the adsorbent and the anionic AB25 molecules. In an aqueous environment, the sulfonate groups of AB25 ionize into their anionic form, as shown:

This reaction facilitates the attraction between the sulfonate groups of AB25 and the positively charged adsorbent surface, represented by the following equations:

Additionally, AB25 contains sulfonic acid functional groups, which are known to have low pKa values (pKa ̴̴ 1) indicating that the dye readily deprotonates in aqueous solutions above pH 2. As a result, AB25 exists predominantly in its anionic form (–SO₃⁻) across the pH range studied (pH 3–11). This consistent negative charge influences how the dye interacts with the surface of the adsorbent. At lower pH values, the protonation of amine and hydroxyl groups on CSAH10 enhances the surface’s positive charge, leading to strong electrostatic attraction between the cationic adsorbent and the anionic dye. As the pH increases, deprotonation of these functional groups reduces the surface charge, weakening these interactions. Although the structural form of AB25 remains largely unchanged above pH 3 due to its low pKa, the electrostatic driving force for adsorption diminishes at higher pH because of changes in the adsorbent’s surface charge rather than the dye itself.

Additionally, with increasing pH, the number of positively charged sites available on the surface of the adsorbent decreases, leading to reduced electrostatic attraction and, hence, a decreased capacity for AB25 adsorption. The presence of various functional groups in these adsorbents, demonstrated by FTIR spectra, does suggest that other mechanisms, such as hydrogen bonding and chemical adsorption, may also be involved in this process. From these results, pH 3 was chosen as an optimum pH for all further adsorption experiments since it increases the electrostatic attraction between the adsorbent and dye molecules.

Adsorption mechanism of AB25 onto CSAH

The adsorption of AB25 onto the CSAH composite is driven by multiple interactions between the functional groups of the adsorbent and the dye molecules. Under acidic conditions (pH 3), the amino groups (–NH₂) of chitosan are protonated to –NH₃⁺, and the carboxyl (–COOH) and hydroxyl (–OH) groups of alginate are also partially protonated, forming –COOH₂⁺ and –OH₂⁺. These positively charged sites form strong electrostatic attractions with the anionic sulfonate groups (–SO₃⁻) of AB2545. Additionally, hydrogen bonding occurs between the hydroxyl and carboxyl groups of the adsorbent and the oxygen atoms in the sulfonate or hydroxyl groups of AB25. The tubular halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) contribute to adsorption through their surface –OH groups, which participate in hydrogen bonding with dye molecules and provide additional active sites46. The following representative interactions can occur: RNH₃⁺⋯SO₃⁻, ROH₂⁺⋯SO₃⁻, and RCOOH₂⁺⋯SO₃⁻, enhancing the overall binding of AB25. As the pH increases, deprotonation reduces the number of positively charged sites, weakening electrostatic attractions and resulting in decreased adsorption. Thus, the high removal efficiency observed at low pH can be attributed to the synergistic effects of electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and the structural contribution of HNTs47. This mechanism is well described in the Fig. 9.

Effect of the HNTs ratio on the adsorption process

The effect of the HNTs ratio in chitosan–sodium alginate–halloysite nanotube (CSAH) composites was evaluated using an adsorbent dosage of 2 g/L, an initial AB25 concentration of 50 mg/L, solution pH of 3, and a contact time of 2 h at 27 °C. The dye removal efficiency for various HNT loadings is shown in Fig. 10. As the HNT content increased from 5 to 10%, the maximum dye removal improved from 84.3 to 93.8%, indicating enhanced adsorption capacity. However, further increases in HNT loading to 15%, 20%, and 30% resulted in a gradual decline in removal efficiency to 88.3%, 82.9%, and 81.3%, respectively. Therefore, CSAH10 (with 10% HNT by weight relative to CSA) was identified as the optimal formulation.

This trend can be explained by considering both the structural and chemical characteristics of the composite. Halloysite nanotubes contribute additional functional groups (mainly hydroxyl groups on their inner and outer surfaces) and increase surface area and porosity, as supported by BET and FTIR analyses. At 10% loading, these enhancements appear to synergize with the functional groups in chitosan (–NH₂) and alginate (–COOH, –OH), facilitating stronger electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding with the anionic AB25 dye. Moreover, the XRD pattern of CSAH10 shows preserved crystalline peaks from both HNTs and the biopolymer matrix, suggesting good structural integration without excessive aggregation60. However, when the HNT ratio exceeds 10%, excessive halloysite content may lead to the partial coverage or blockage of active binding sites on the CSA matrix. This reduces the accessibility of dye molecules to key adsorption sites. Additionally, too much inorganic filler can disrupt the polymer network’s homogeneity and reduce the swelling capacity and flexibility of the composite, thereby lowering overall performance. Thus, the CSA-to-HNT weight ratio in CSAH10 achieves a critical balance—providing sufficient additional active sites from HNTs while maintaining the accessibility and functionality of the biopolymer matrix61.

Adsorption isotherm study

Adsorption isotherm data shows how adsorbate interacts with the adsorbent and provides detailed results about the mechanism of the adsorption processes. The isotherm studies for CSAH10 were conducted with an adsorbent dosage of 2 g/L, initial concentration of 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 and 600 mg/L, pH solution of 3 and constant temperature of 27 °C for about 2 h. In this regard, contact between the adsorbent and adsorbate was continued until the equilibrium point. The adsorption isotherm data shows the relative changes of equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) versus equilibrium concentration of adsorbate (Ce)62. The initial concentration of dye significantly influences the adsorption characteristics of the CSAH10 composite. As the AB25 concentration increased from 25 to 600 mg/L, a corresponding rise in equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) was observed. This can be explained by the enhanced concentration gradient at higher dye levels, which improves mass transfer and promotes greater interaction between dye molecules and the adsorbent’s active sites. At lower concentrations, fewer dye molecules are available to occupy these sites, resulting in reduced adsorption. In contrast, higher concentrations lead to a more substantial loading of dye onto the adsorbent until surface sites begin to reach saturation.

To describe adsorption capacity, analysis and design of adsorption systems, the isotherm models are used commonly. The Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, Redlich-Peterson and Toth isotherm models are used to interpret the equilibrium adsorption data (Supplementary data S. 1). These models establish the relationship between the concentration of the adsorbate at equilibrium and the amount of solute adsorbed onto the adsorbent at a constant temperature63.

The fitted parameters, coefficient of determination (\(\:{\text{R}}^{2}\), supplementary data) and the absolute average relative deviation (AARD, supplementary data) values are summarized in Table 3. Among the models tested, the Freundlich, Toth, and Redlich-Peterson models provided the best fits to the experimental data, with \(\:{\text{R}}^{2}\) values of 0.9987, 0.9996, and 0.9994, respectively, and AARD values of 11.2717%, 4.4696%, and 5.7805%, respectively. The Toth model, with the highest \(\:{\text{R}}^{2}\) and lowest AARD, showed the best agreement with the experimental data, indicating that the adsorption of AB25 onto the CSAH10 composite occurs in a heterogeneous system64. Additionally, the maximum adsorption capacity of CSAH10 for AB25, based on the Langmuir model, was calculated to be 351.07 mg/g, as shown in Table 3. The experimental isotherm data, along with the Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, Redlich-Peterson, and Toth models, are depicted in supplementary data Fig. 3A. The experimental data clearly demonstrate a nonlinear increase in adsorption capacity (qe) with increasing equilibrium concentration (Ce), confirming that the adsorption process is concentration-dependent and does not follow a strictly linear trend. At lower dye concentrations, qe increases gradually, suggesting that ample active sites are available on the CSAH10 surface, and adsorption proceeds efficiently via monolayer coverage18. As the concentration increases beyond this range (toward 400–600 mg/L), the rate of increase in qe becomes more pronounced, indicating a shift toward multi-layer adsorption or site saturation effects where higher dye molecule density enhances surface coverage through interactions beyond just active site availability. This behavior supports the presence of heterogeneous surface energy distribution, as evidenced by the better fit of nonlinear isotherm models such as Toth, Redlich–Peterson, and Freundlich. These models, which account for site heterogeneity and variable affinity, align closely with the experimental data across the full range of concentrations. Thus, the experimental trend not only reinforces the capacity of CSAH10 to adsorb higher dye loads effectively but also validates the selection of complex isotherm models to capture the equilibrium behavior of the system more accurately than simpler models like Langmuir65.

Comparative adsorption capacity of CSAH10 and other adsorbents

Comparative data for CSAH10 and other adsorbents from the literature are also provided in Table 4. It is evident that the CSAH10 adsorbent used in this study demonstrates a higher adsorption capacity in comparison with most of the adsorbents, including chitosan (48.8 mg/g)66, cross-linked chitosan beads (127 mg/g)67, and some modified adsorbents like BGFS-CTAB (166.67 mg/g)68 and Zeolite-CTAB (112.44 mg/g)69. Although adsorption capacity of CSAH10 is lower than the adsorption capacity of pectin derived from pomelo peel (719.4 mg/g)70, which is rich in some functional group like hydroxyl (\(\:-\text{O}\text{H}\)), carboxylate (\(\:{\text{C}\text{O}\text{O}}^{-}\)), and ester (\(\:{-\text{C}\text{O}\text{O}\text{C}\text{H}}_{3}\)), the CSAH10 showed notable performance due to the synergistic effect of chitosan and alginate. The presence of amino (\(\:{-\text{N}\text{H}}_{2}\)) groups in chitosan and carboxylate groups in alginate facilitates efficient dye binding through electrostatic interactions, making CSAH10 a competitive alternative for AB25 removal despite its lower overall adsorption capacity42.

Kinetic study

The effect of contact time for CSA and CSAH10 was investigated by using an adsorbent dosage of 2 g/L, initial concentration of 50 mg/L and constant temperature of 27 °C for about 2 h. at various solution pH in the range of 3 to 11. Additionally, the effect of contact time on the adsorption performance of CSA and CSAH composites is clearly illustrated in Fig. 8. As shown, the adsorption process proceeds rapidly within the first 10–20 min for all samples, with CSAH10 achieving the highest dye uptake. This initial phase is dominated by a strong concentration gradient between the dye in the solution and the available active sites on the adsorbent surface, which facilitates fast external diffusion and surface interaction. As time progresses, the rate of adsorption gradually decreases, and a plateau is reached, indicating equilibrium. Beyond this point, no significant increase in adsorption capacity is observed, suggesting that the available adsorption sites have been occupied or become less accessible due to steric hindrance and adsorbate–adsorbent repulsion. Notably, CSAH10 reaches equilibrium more quickly and with higher dye removal compared to other formulations, which is attributed to the enhanced porosity and availability of active functional groups from the halloysite nanotubes. These observations confirm that reaction time is a critical factor in determining adsorption efficiency and kinetics, especially during the early stages of the process where most dye uptake occurs18.

The process of conventional adsorption is conventionally divided into four steps: the transportation of AB25 molecules from the bulk solution to the outer layer of the adsorbent, external diffusion from the solution film to the bulk surface of the adsorbent, intraparticle diffusion, and adsorption-desorption interactions of AB25 molecules at the active sites of the adsorbent83. The kinetic study of the adsorption process is one of the methods for investigating the rate of dye molecules’ adsorption. Also, kinetic studies play a significant role in the design of adsorption-based systems. The kinetics of adsorption processes depend highly upon the physical and chemical characteristics of the adsorbent and show the mechanism of the process. Commonly, the forecasting of adsorption rate and computation of kinetic parameters by models usually applied in kinetic investigations have great importance in designing and modeling the adsorption systems. The kinetic modeling of AB25 adsorption to the tested adsorbents was determined using two different kinetic models, namely the pseudo-first-order kinetic model and the pseudo-second-order kinetic model84. In these models, the idea is based on the assumption that adsorption in the adsorbent’s surface is the only factor controlling adsorption systems. The intraparticle diffusion model and the Elovich kinetic model were thus applied in the study of the mechanistic approach to the adsorption process. More explanation is provided in supplementary data S. 2.

In the pseudo-first-order kinetic model, the rate of adsorption is assumed to be proportional to the number of adsorption active sites of the adsorbent58. The validity of each model was studied using the coefficient of determination (R2, supplementary data) and absolute average relative deviation (AARD, supplementary data) as an error function to interpret the conformity of the calculated parameters with the experimental data. In this approach, the nonlinear least-squares function provided by MATLAB software was utilized. For AB25 regarding the CSA and CSAH10 adsorbents, the parameters corresponding to the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models, R2 and AARD for each solution pH value are tabulated in Table 5. This reflects that the AARD value in the pseudo-second-order is less for CSA adsorbent compared to the pseudo-first-order, and the R2 value in the pseudo-second-order indicates that this model and the experimental data are in good agreement. Also, the same trend was realized for the CSAH10 adsorbent, and both CSA and CSAH10 adsorbent since R2 has a great value and AARD has a low value. The pseudo-second-order kinetic model is the one governing the adsorption process. Moreover, the effect of HNTs ratio on contact time and kinetic study was investigated by various HNTs ratios that varied from 5 to 30%, as shown in Fig. 10, at an adsorbent dosage of 2 g/L, an initial concentration of 50 mg/L, pH solution of 3 at constant temperature at 27 °C for about 2 h. Additionally, the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic model parameters for all ratios of HNTs are reported in Table 6. From this table, it can be realized that for all cases of the adsorbent studied, the AARD value for a pseudo-second-order model is smaller than a pseudo-first-order model, and also R2 value for a pseudo-second-order model shows that there is a strong correlation between this model and experimental data. Also, the very high value of R2 and low value of AARD prove that the pseudo-second-order kinetic model is a governing mode in the adsorption process. The intraparticle diffusion model equation (supplementary data S. 2), which was conducted by testing the model as the rate-limiting step using the model, is investigated and the parameters are obtained by the method proposed for the calculation of pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order parameters. The calculated parameters are tabulated in Tables 7 and 8. In Table 7, intraparticle diffusion model parameters, R2 and AARD for CSA and CSAH10 adsorbents are listed. The same parameters are listed for CSAH with various HNTs ratios in Table 8. All the data obtained in the study of the intraparticle diffusion curve fitting reveal that the value of the coefficient of determination related to the intraparticle diffusion model is low and also the high value of AARD shows the inapplicability of the intraparticle diffusion model in explaining adsorption kinetic. Figure 6A from Supplementary data illustrates that the intraparticle diffusion models do not go through the origin, which indicates that the adsorption process of AB25 onto adsorbents is controlled by both boundary and intraparticle diffusion mechanisms. Hence, the intraparticle diffusion does not become the rate-controlling step solely for the adsorption process of AB25 onto adsorbents. The high values of constant C obtained from the Tables 7 and 8, indicate great affection for the boundary layer on the AB25 molecules’ diffusion83.

Elovich kinetic model, R2, and AARD parameters for CSA and CSAH10 adsorbents and different HNTs ratios of CSAH adsorbent are presented in Tables 9 and 10. All obtained data from the curve fitting study reveals that the value of the coefficient of determination for the Elovich model is low and also, the high value of AARD reveals the inapplicability of the Elovich kinetic model to explain the adsorption kinetic. The experimental kinetic data, along with the pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, intraparticle diffusion and Elovich kinetic models (The best fit) are depicted in supplementary data Fig. 4A.

Cost assessment of adsorbent preparation

Assessing the cost-effectiveness of the CSAH10 composite is crucial for evaluating its practical viability in dye wastewater treatment. The total production cost of the adsorbent includes the cost of raw materials and energy consumption during synthesis. The adsorbent was prepared from chitosan, sodium alginate, and halloysite nanotubes in a 1:1:0.2 mass ratio (i.e., 10 wt% HNTs relative to the CSA polymer matrix). The cost per gram of dye removed was calculated using the following expression38:

AC refers to the adsorption cost per gram of pollutant removed, while q represents the adsorption capacity of CSAH10. Cost of chemicals is calculated based on the proportions used, and cost of energy is estimated from freeze-drying and stirring operations. Among the various components used in adsorbent preparation, chitosan is the most expensive, often serving as the primary factor influencing the overall production cost. For comparison purpose, the chitosan/cellulose composite developed for chromium removal, the reported adsorbent cost reached approximately $0.62 per gram of adsorbate. Additionally, the production cost of magnetic chitosan-functionalized graphene oxide used for removing Reactive Black 5 was estimated at 127.7 USD per kilogram38. Using Eq. 7 and the estimated wholesale prices of the raw materials sourced from common markets, the adsorption cost per gram of AB25 removed (AC) for the CSAH10 composite—featuring a maximum adsorption capacity of 351.07 mg/g—was calculated to be approximately $1.08/g. Despite the relatively high-cost contribution from chitosan, the composite remains economically promising due to its efficient dye uptake, fast kinetics, and reusability. The balanced combination of cost-effectiveness and adsorption performance positions CSAH10 as a viable and competitive alternative to many conventionally reported adsorbents.

Adsorbent reuse study

The experiment on regeneration explores the possibility of a different route for direct disposal of spent adsorbent, where the potential to recycle the spent adsorbent may decrease the overall costs related to adsorbent treatment. A dosage of 2 g/L adsorbent, an initial concentration of 50 mg/L, pH 3, and a constant temperature of 27 °C were used in running the reuse and regeneration of CSAH10 for five cycles, each lasting about 2 h. For the reactivation of the used adsorbents, 0.1 M sodium hydroxide solution was used in the experiment. The experimental testing focused on the potential sustainability of the adsorbent, especially in successive processes of adsorption. The results are shown in supplementary data Fig. 5A. As can be observed, the difference between the first and the last cycle is obtained 39%. The calculated percentage removal efficiency was 91.2 ± 2.3%, 83.1 ± 1.8%, 75.7 ± 1.2%, 60.8 ± 1.4% and 57.7 ± 2.4% for 5 successive cycles. If the adsorption process were fully reversible, all AB25 molecules would have been desorbed. The 91.2% removal observed in the first regeneration cycle suggests that most of the adsorbent’s active sites were effectively restored85. This indicates predominantly weak interactions between AB25 molecules and high-energy adsorption sites, which is advantageous for desorption and enhances the material’s regeneration potential. The adsorption capacities in the first and fifth cycles were 22.79 ± 0.57 mg/g and 14.42 ± 0.61 mg/g, respectively, indicating a moderate decline after five regeneration cycles. In comparison, previous studies reported a more substantial decrease in the adsorption capacity of modified halloysite for Congo Red, dropping from 60 to 30 mg/g over five cycles86. This comparison suggests that the adsorbent used in the present study exhibits better regeneration stability and retains a higher proportion of its initial adsorption performance.

It can be explained that at the high pH of the solution, the adsorbent surface becomes predominantly negatively charged and causes the repulsion of anionic AB25 molecules. In the pH experiment, it was observed that the adsorption of AB25 was unfavorable in high pH; this may account for the effectiveness of the base in desorbing AB25 from the adsorbents. In such an unfavorable condition, the interaction between AB25 and the adsorbent might be weakened and be easily displaced by the \(\:{\text{O}\text{H}}^{-}\) present.

Conclusion

This study investigated the removal of Acid Blue 25 (AB25) dye from aqueous solutions using chitosan/sodium alginate (CSA) and chitosan/sodium alginate/halloysite nanotube (CSAH) composites. Characterization confirmed the structural and surface properties of the adsorbents. The CSAH10 composite, containing 10% halloysite nanotubes, showed superior performance, achieving 94% dye removal within 30 min—an improvement over CSA, which reached 80% in 70 min. Isotherm analysis indicated that the Toth model best described the adsorption behavior, while kinetic studies revealed that the process followed a pseudo-second-order model, suggesting chemisorption. The maximum adsorption capacity of CSAH10 was 351 mg/g. The enhanced performance was attributed to the synergistic effects of electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and the additional active sites provided by the nanotubes. Regeneration tests demonstrated the reusability of CSAH10, with efficiency declining moderately from 91 to 58% over five cycles. Overall, CSAH10 is an effective, eco-friendly, and cost-efficient adsorbent for AB25 removal, particularly under acidic conditions.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Bhattacharya, S., Bar, N., Rajbansi, B. & Das, S. K. Adsorptive elimination of Cu(II) from aqueous solution by chitosan-nanoSiO2 nanocomposite—Adsorption study, MLR, and GA modeling. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 232, 161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-021-05070-x (2021).

Zhang, P. et al. Ordered mesoporous materials for water pollution treatment: adsorption and catalysis. Green. Energy Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gee.2023.11.001 (2023).

Mirzaei, S. & Javanbakht, V. Dye removal from aqueous solution by a novel dual cross-linked biocomposite obtained from mucilage of Plantago psyllium and eggshell membrane. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 134, 1187–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.119 (2019).

Kazemi, J. & Javanbakht, V. Alginate beads impregnated with magnetic chitosan@zeolite nanocomposite for cationic methylene blue dye removal from aqueous solution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 154, 1426–1437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.024 (2020).

Ghodbane, H. & Hamdaoui, O. Decolorization of antraquinonic dye, C.I. Acid Blue 25, in aqueous solution by direct UV irradiation, UV/H2O2 and UV/Fe(II) processes. Chem. Eng. J. 160, 226–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2010.03.049 (2010).

Ghanei, M., Rashidi, A., Tayebi, H. A., Yazdanshenas, M. E. & Rezainejad, H. Adsorption of Acid Blue 25 dye by CPAA coated on SBA-15 in aqueous solution: A density functional theory study. Synth. Met. 269, 116568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synthmet.2020.116568 (2020).

Krishna, L. S., Yuzir, A., Yuvaraja, G. & Ashokkumar, V. Removal of Acid Blue 25 from aqueous solutions using Bengal gram fruit shell (BGFS) biomass. Int. J. Phytorem. 19, 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/15226514.2016.1244161 (2017).

Radoor, S., Kassahun, S. K. & Kim, H. Selective adsorption of cationic dye by κ-carrageenan-potato starch bio-hydrogel: kinetics, isotherm, and thermodynamic studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 281, 136377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136377 (2024).

Golie, W. M. & Upadhyayula, S. An investigation on biosorption of nitrate from water by chitosan based organic-inorganic hybrid biocomposites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 97, 489–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.066 (2017).

Kanakaraju, D., Glass, B. D. & Oelgemöller, M. Advanced oxidation process-mediated removal of pharmaceuticals from water: A review. J. Environ. Manage. 219, 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.04.103 (2018).

Levchuk, I., Rueda Márquez, J. J. & Sillanpää, M. Removal of natural organic matter (NOM) from water by ion exchange – A review. Chemosphere 192, 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.10.101 (2018).

Sevda, S., Sreekishnan, T. R., Pous, N., Puig, S. & Pant, D. Bioelectroremediation of perchlorate and nitrate contaminated water: A review. Bioresour Technol. 255, 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2018.02.005 (2018).

Sadri Moghaddam, S., Alavi Moghaddam, M. R. & Arami, M. Coagulation/flocculation process for dye removal using sludge from water treatment plant: optimization through response surface methodology. J. Hazard. Mater. 175, 651–657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.10.058 (2010).

da Medeiros, D. C. C., Chelme-Ayala, P. & Gamal El-Din, M. Sludge-based activated Biochar for adsorption treatment of real oil sands process water: selectivity of naphthenic acids, reusability of spent Biochar, leaching potential, and acute toxicity removal. Chem. Eng. J. 463, 142329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.142329 (2023).

Vinardell, S., Astals, S., Mata-Alvarez, J. & Dosta, J. Techno-economic analysis of combining forward osmosis-reverse osmosis and anaerobic membrane bioreactor technologies for municipal wastewater treatment and water production. Bioresour Technol. 297, 122395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122395 (2020).

Sabarish, R. & Unnikrishnan, G. Polyvinyl alcohol/carboxymethyl cellulose/ZSM-5 zeolite biocomposite membranes for dye adsorption applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 199, 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.123 (2018).

Radoor, S. et al. Low-cost and eco-friendly pva/carrageenan membrane to efficiently remove cationic dyes from water: isotherms, kinetics, thermodynamics, and regeneration study. Chemosphere 350, 140990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140990 (2024).

Babazadeh, M., Abolghasemi, H., Esmaeili, M., Ehsani, A. & Badiei, A. Comprehensive batch and continuous Methyl orange removal studies using surfactant modified chitosan-clinoptilolite composite. Sep. Purif. Technol. 267, 118601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2021.118601 (2021).

Dong, K. et al. A study on treatment efficacy of ballast water treatment system applying filtration + membrane separation + deoxygenation technology during shipboard testing. Mar. Pollut Bull. 188, 114620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.114620 (2023).

Bhatnagar, A. & Anastopoulos, I. Adsorptive removal of bisphenol A (BPA) from aqueous solution: A review. Chemosphere 168, 885–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.10.121 (2017). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

Usman, M. et al. Magnetite and green rust: synthesis, properties, and environmental applications of mixed-valent iron minerals. Chem. Rev. 118, 3251–3304. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00224 (2018).

Ajmal, Z. et al. Phosphate removal from aqueous solution using iron oxides: adsorption, desorption and regeneration characteristics. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 528, 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2018.05.084 (2018).

Leudjo Taka, A., Klink, M. J., Yangkou Mbianda, X. & Naidoo, E. B. Chitosan nanocomposites for water treatment by fixed-bed continuous flow column adsorption: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 255, 117398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117398 (2021).

Bhattacharya, S., Bar, N., Rajbansi, B. & Das, S. K. Adsorptive elimination of methylene blue dye from aqueous solution by chitosan-nSiO2 nanocomposite: adsorption and desorption study, scale-up design, statistical, and genetic algorithm modeling. Environ. Prog Sustain. Energy. 43, e14282. https://doi.org/10.1002/ep.14282 (2024).

Rizeq, B. R., Younes, N. N., Rasool, K. & Nasrallah, G. K. Synthesis, bioapplications, and toxicity evaluation of chitosan-Based nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20225776 (2019).

Bhattacharya, S., Bar, N., Rajbansi, B. & Das, S. K. Synthesis of chitosan-nTiO2 nanocomposite, application in adsorptive removal of Cu(II)—Adsorption and desorption study, mechanism, scale-up design, statistical, and genetic algorithm modeling. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 37, e7094. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.7094 (2023).

Morais da Silva, P. M. et al. Effective removal of basic dye onto sustainable chitosan beads: batch and fixed-bed column adsorption, beads stability and mechanism. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 18, 100348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2020.100348 (2020).

Kurczewska, J., Cegłowski, M. & Schroeder, G. Alginate/PAMAM dendrimer – Halloysite beads for removal of cationic and anionic dyes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 123, 398–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.119 (2019).

Verma, A. et al. Graphite modified sodium alginate hydrogel composite for efficient removal of malachite green dye. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 148, 1130–1139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.142 (2020).

Biswas, S., Mohapatra, S. S., Kumari, U., Meikap, B. C. & Sen, T. K. Batch and continuous closed circuit semi-fluidized bed operation: removal of MB dye using sugarcane Bagasse biochar and alginate composite adsorbents. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8, 103637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2019.103637 (2020).

ALSamman, M. T. & Sánchez, J. Recent advances on hydrogels based on chitosan and alginate for the adsorption of dyes and metal ions from water. Arab. J. Chem. 14, 103455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103455 (2021).

Zubair, M. & Ullah, A. Chap. 14 - Biopolymers in Environmental Applications: Industrial Wastewater Treatment. (Thomas, S., Gopi, S. Eds.). 331–349 . (Elsevier, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819240-5.00014-6

Szczepanik, B. Photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants over clay-TiO2 nanocomposites: A review. Appl. Clay Sci. 141, 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2017.02.029 (2017). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

Yuan, P., Tan, D. & Annabi-Bergaya, F. Properties and applications of Halloysite nanotubes: recent research advances and future prospects. Appl. Clay Sci. 112–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2015.05.001 (2015).

Bessaha, G. et al. Enhancement of the comprehensive performance of Tetracycline adsorption by Halloysite nanotubes: kinetics, mechanism, and reusability study, desalin. Water Treat. 320, 100695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dwt.2024.100695 (2024).

Nyankson, E. & Kumar, R. V. Removal of water-soluble dyes and pharmaceutical wastes by combining the photocatalytic properties of Ag3PO4 with the adsorption properties of Halloysite nanotubes. Mater. Today Adv. 4, 100025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtadv.2019.100025 (2019).

Fakhruddin, K. et al. Halloysite nanotubes and halloysite-based composites for biomedical applications. Arab. J. Chem. 14, 103294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103294 (2021).

Mosaffa, E. et al. Enhanced adsorption removal of Levofloxacin using antibacterial LDH-biochar cross-linked chitosan/pva beads through batch and column approaches; comprehensive isothermal and kinetic study. Desalination 599, 118452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2024.118452 (2025).

Bessaha, F., Marouf-Khelifa, K., Batonneau-Gener, I. & Khelifa, A. Characterization and application of heat-treated and acid-leached Halloysites in the removal of malachite green: adsorption, desorption, and regeneration studies. Desalin. Water Treat. 57, 14609–14621. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443994.2015.1063090 (2016).

Arni, L. A. et al. Fabrication of magnetic chitosan-grafted salicylaldehyde/nanoclay for removal of Azo dye: BBD optimization, characterization, and mechanistic study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 248, 125943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125943 (2023).

Jawad, A. H., Abdulhameed, A. S., Reghioua, A. & Yaseen, Z. M. Zwitterion composite chitosan-epichlorohydrin/zeolite for adsorption of methylene blue and reactive red 120 dyes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 163, 756–765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.014 (2020).

Sabbagh, N., Tahvildari, K. & Mehrdad Sharif, A. A. Application of chitosan-alginate bio composite for adsorption of malathion from wastewater: characterization and response surface methodology. J. Contam. Hydrol. 242, 103868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2021.103868 (2021).

Bajpai, A. K. Facile Preparation of ionotropically crosslinked chitosan-alginate nanosorbents by water-in-oil (W/O) microemulsion technique: optimization and study of arsenic (V) removal. J. Water Process. Eng. 32, 100920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2019.100920 (2019).

Dubey, R., Bajpai, J. & Bajpai, A. K. Chitosan-alginate nanoparticles (CANPs) as potential nanosorbent for removal of Hg (II) ions, environ. Nanotechnology. Monit. Manag. 6, 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enmm.2016.06.008 (2016).

Wen, Z. et al. Three-dimensional porous adsorbent based on chitosan-alginate-cellulose sponge for selective and efficient removal of anionic dyes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 110831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2023.110831 (2023).

Erdem, S., Öztekin, M. & Sağ Açıkel, Y. Investigation of Tetracycline removal from aqueous solutions using Halloysite/chitosan nanocomposites and Halloysite nanotubes/alginate hydrogel beads. Environ. Nanatechnol. Monit. Manag. 16, 100576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enmm.2021.100576 (2021).

Liu, M., Dai, L., Shi, H., Xiong, S. & Zhou, C. In vitro evaluation of alginate/halloysite nanotube composite scaffolds for tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 49, 700–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2015.01.037 (2015).

Paul, A. et al. Halloysite nanotube and Chitosan polymer composites: physicochemical and drug delivery properties. J. Drug Deliv Sci. Technol. 72, 103380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103380 (2022).

Radoor, S., Karayil, J., Jayakumar, A., Parameswaranpillai, J. & Siengchin, S. Efficient removal of Methyl orange from aqueous solution using mesoporous ZSM-5 zeolite: synthesis, kinetics and isotherm studies. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 611, 125852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125852 (2021).

Mexicana, R. & De, I. Q. Preparation and characterization of Chitosan / Carbon. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2, 205–211 (2006).

Ionita, M., Pandele, M. A. & Iovu, H. Sodium alginate/graphene oxide composite films with enhanced thermal and mechanical properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 94, 339–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.01.065 (2013).

Kanti, P., Srigowri, K., Madhuri, J., Smitha, B. & Sridhar, S. Dehydration of ethanol through blend membranes of Chitosan and sodium alginate by pervaporation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 40, 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2004.03.003 (2004).

Mosaffa, E., Patel, R. I., Banerjee, A., Basak, B. B. & Oroujzadeh, M. Comprehensive analysis of cationic dye removal from synthetic and industrial wastewater using a semi-natural Curcumin grafted biochar/poly acrylic acid composite hydrogel. RSC Adv. 14, 7745–7762. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA08521J (2024).

Viscusi, G., Lamberti, E. & Gorrasi, G. Design of a hybrid bio-adsorbent based on sodium alginate/halloysite/hemp hurd for methylene blue dye removal: kinetic studies and mathematical modeling. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 633, 127925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.127925 (2022).

Amir Afshar, H. & Ghaee, A. Preparation of aminated chitosan/alginate scaffold containing Halloysite nanotubes with improved cell attachment. Carbohydr. Polym. 151, 1120–1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.06.063 (2016).

Li, M. et al. Treatment of potato starch wastewater by dual natural flocculants of Chitosan and poly-glutamic acid. J. Clean. Prod. 264, 121641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121641 (2020).

Lakkaboyana, S. K., Soontarapa, K., Vinaykumar, R. K. & Marella Kannan, K. Preparation of novel Chitosan polymeric nanocomposite as an efficient material for the removal of acid blue 25 from aqueous environment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 168, 760–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.11.133 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. Superior adsorption of Methyl orange by h-MoS2 microspheres: isotherm, kinetics, and thermodynamic studies. Dye Pigment. 170, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dyepig.2019.107591 (2019).

Hanafiah, M. A. K. M., Ngah, W. S. W., Zolkafly, S. H., Teong, L. C. & Majid, Z. A. A. Acid blue 25 adsorption on base treated Shorea dasyphylla sawdust: kinetic, isotherm, thermodynamic and spectroscopic analysis. J. Environ. Sci. 24, 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1001-0742(11)60764-X (2012).

Choo, C. K. et al. Chitosan/halloysite beads fabricated by ultrasonic-assisted extrusion-dripping and a case study application for copper ion removal. Carbohydr. Polym. 138, 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.11.060 (2016).

Ramanayaka, S., Sarkar, B., Cooray, A. T., Ok, Y. S. & Vithanage, M. Halloysite nanoclay supported adsorptive removal of Oxytetracycline antibiotic from aqueous media. J. Hazard. Mater. 384, 121301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121301 (2020).

Brahma, D., Priyom Nath, K., Patgiri, M. & Saikia, H. Synthesis of ternary CaNiAl-Layered double hydroxide as potential adsorbent for congo red dye removal in aqueous solution. Asian J. Chem. 34, 3215–3223. https://doi.org/10.14233/ajchem.2022.23977 (2022).

Brahma, D. & Saikia, H. and Surfactants assisted synthesis of CuAl-sodium Dodecyl sulfate layered double hydroxide and its adsorptive removal of Methyl red dye from aqueous solution. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 53, 605–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/24701556.2023.2166074 (2023).

Al-Ghouti, M. A. & Da’ana, D. A. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of adsorption isotherm models: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 393, 122383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122383 (2020).

Babazadeh, M., Irannezhad, M., Abolghasemi, H., Hosseiniyan, S. B. & Ehsani, A. 3D mathematical modeling of external mass transfer effect in high-rate adsorption process. Surf. Interfaces. 29, 101771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2022.101771 (2022).

Juang, R., Tseng, R., Wu, F. & Lin, S. Use of Chitin and Chitosan in Lobster shell wastes for color removal from aqueous solutions. J. Environ. Sci. Heal Part. Environ. Sci. Eng. Toxicol. 31, 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/10934529609376360 (1996).

Chiou, M. S., Ho, P. Y. & Li, H. Y. Adsorption of anionic dyes in acid solutions using chemically cross-linked Chitosan beads. Dye Pigment. 60, 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0143-7208(03)00140-2 (2004).

Krishna, L. S., Soontarapa, K., Asmel, N. K., Yuzir, A. & Zuhairi, W. Y. W. Effect of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide on the biosorption of Acid Blue 25 onto Bengal gram fruit shell, desalin. Water Treat. 150, 386–395. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2019.23765 (2019).

Krishna, L. S. et al. Adsorption of Acid Blue 25 from aqueous solution using zeolite and surfactant modified zeolite. Desalin. Water Treat. 150, 348–360. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2019.23726 (2019).

Shahrin, E. W. E. S. et al. Pectin derived from pomelo pith as a superior adsorbent to remove toxic Acid Blue 25 from aqueous solution. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2, 100116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carpta.2021.100116 (2021).

Sarwar, H. et al. Adsorption kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies for the removal of acid blue 25 from wastewater by using modified sugarcane bagasse, desalin. Water Treat. 312, 247–257. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2023.30067 (2023).

Ahmed, T., Ali, A. M. & Sen Gupta, S. Application of NFO-GO composite for the removal of acid blue 25 toxic dye from aqueous solution. Desalin. Water Treat. 174, 400–413. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2020.24884 (2020).

Tovar-Gómez, R. et al. Synergic adsorption in the simultaneous removal of Acid Blue 25 and heavy metals from water using a Ca(PO3)2-modified carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 199–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.11.015 (2012).

Saheed, I. O., Oh, W. D. & Suah, F. B. M. Enhanced adsorption of Acid Blue-25 dye onto chitosan/porous carbon composite modified in 1-allyl-3-methyl imidazolium bromide ionic liquid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 183, 1026–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.042 (2021).

Haque, A. N. M. A., Remadevi, R., Wang, X. & Naebe, M. Adsorption of anionic Acid Blue 25 on chitosan-modified cotton gin trash film. Cellulose 27, 9437–9456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-020-03409-x (2020).

Dahri, M. K., Lim, L. B. L., Priyantha, N. & Chan, C. M. Removal of Acid Blue 25 using Cempedak Durian Peel from aqueous medium: isotherm, kinetics and thermodynamics studies. Int. Food Res. J. 23, 1154–1163 (2016). https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:102432346

Sivarama Krishna, W. Z. W. Y., Lakkaboyana, S., Khantong, M. A., Kabir, Y. & Ali Removal of Acid Blue 25 dye from wastewater using Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum Linn.) seed as an efficient natural biosorbent. Indian J. Adv. Chem. Sci. 2. 6 (3), 2018. https://doi.org/10.22607/IJACS.2021.904017 (2018).

Shahrin, E. W. E. S. et al. Adsorption behavior and dynamic interactions of anionic Acid Blue 25 on agricultural waste. Molecules 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27051718 (2022).

Kooh, M. R. R., Dahri, M. K., Lim, L. B. L. & Lim, L. H. Batch adsorption studies on the removal of Acid Blue 25 from aqueous solution using Azolla pinnata and soya bean waste. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 41, 2453–2464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-015-1877-5 (2016).

Jain, S. N. & Gogate, P. R. NaOH-treated dead leaves of Ficus racemosa as an efficient biosorbent for Acid Blue 25 removal. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 14, 531–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-016-1160-7 (2017).

Ghanei, M., Rashidi, A., Tayebi, H. A. & Yazdanshenas, M. E. Removal of Acid Blue 25 from aqueous media by magnetic-SBA-15/CPAA super adsorbent: Adsorption isotherm, kinetic, and thermodynamic studies. J. Chem. Eng. Data 63 3592–3605. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jced.8b00474. (2018).

Auta, M. & Hameed, B. H. Preparation of waste tea activated carbon using potassium acetate as an activating agent for adsorption of Acid Blue 25 dye. Chem. Eng. J. 171, 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2011.04.017 (2011).

Bhattacharya, S., Bar, N., Rajbansi, B. & Das, S. K. Chitosan-nTiO2 nanocomposite synthesis and its adsorptive removal capacity for methylene blue from its aqueous solution: Batch adsorption study and modeling. ChemistrySelect 9, e202400903. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202400903

Sabarish, R. & Unnikrishnan, G. PVA/PDADMAC/ZSM-5 zeolite hybrid matrix membranes for dye adsorption: fabrication, characterization, adsorption, kinetics and antimicrobial properties. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 6, 3860–3873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2018.05.026 (2018).

Mosaffa, E. et al. Bioinspired chitosan/pva beads cross-linked with LTH-doped bacterial cellulose hydrochar for high-efficiency removal of antibiotics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 306, 141522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.141522 (2025).

Bessaha, F., Mahrez, N., Marouf-Khelifa, K., Çoruh, A. & Khelifa, A. Removal of congo red by thermally and chemically modified halloysite: equilibrium, FTIR spectroscopy, and mechanism studies. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 16, 4253–4260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-018-2041-z (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our special appreciation and thanks to Professor Dr. Bart Van der Bruggen for his helpful discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ali Farzaneh: Data curation, Validation, Conceptualization, Mohammadreza Bababzadeh: Software, Writing- Original draft preparation, Supervision, Validation, Conceptualization, Hossein Ganjidoust: Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Ali Ehsani: Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Conceptualization, Supervision, Mojtaba Hadi: Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions