Abstract

The WHO estimates that postpartum depression occurs in 13–20% of women. It is underdiagnosed and undervalued. The aim is to analyze the prevalence and factors associated with the risk of postpartum depression in times of Pandemic in puerperal women in Baixo-Alentejo, Portugal. Cross-sectional study with 301 participants. The online questionnaire collected sociodemographic data, characteristics of pregnancy, childbirth, puerperium, and also the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The statistical analysis used IBM-SPSS. After bivariate analysis, variables with a p-value < .25 were selected. Logistic regression was performed on the potential predictors. Ethical principles were respected. The average age of the participants was 31.35 years (SD = 5.80). At an EPDS total score cut-off of 10, the prevalence of the risk of postpartum depression was 27.57%. Three protective factors associated with the risk of postpartum depression were: a) feeling safe during childbirth (OR .958, 95% CI .942–.974, B = − .043), b) being accompanied in labor by a family member (OR .342, 95% CI .163–.715, B = − 1.074) and c) planning the pregnancy (OR .209, 95% CI .109–.397, B = − 1.568). The model explained 34.3% of the variance in the risk of postpartum depression. The study suggests the need for local health policies. Potentiation of short- and long-term morbidities must be avoided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The risk of Postpartum Depression (PPD) expresses a woman’s vulnerability after the birth of her child. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates a prevalence of 13–20% among puerperal women, with geographical fluctuations1.

The diagnosis of PPD is based on at least five symptoms that have been present for at least two weeks. Anhedonia occurs, in addition to five of the nine standard symptoms (i.e. insomnia/hypersomnia, fatigue or lack of energy, lack of interest, agitation or low activity, depressed mood, changes in weight, feeling worthless or excessive/inappropiate guilt, decreased concentration, suicidal ideation/attempts…)2. The ICD-10 understands that there are mental disorders associated with the puerperium if they begin within 6 weeks of birth. The DSM-V reports the time frame from pregnancy to 4 weeks postpartum. Other literature consider a diagnosis of PPD if the disorders begin 3–6 months postpartum and empirical studies consider up to 1 year postpartum3.

One of the most widely used instruments for assessing the risk of PPD is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). The cut-off point for EDPS in the postpartum phase differs between studies. In the Japanese population, the cut-off point of 8/9, at the end of the 1st month of puerperium, was the most appropriate4 and in a systematic review with meta-analysis, an EPDS cut-off point ≥ 11 maximized the combined sensitivity and specificity5. In Portugal, the Directorate-General for Health (DGH) version locates the cut-off point at a score ≥ 126, considering it a reason for referral to a psychology consultation. In addition, there are cases where any category ≥ 1 is marked in item 10, corresponding to punitive or suicidal ideation6,7. However, in populations where the risk of PPD is poorly studied, the suggested cut-off point for the puerperal woman is ≥ 108. This perspective argues for greater effectiveness in identifying the risk of mild to major depression7,8, also avoiding false negatives5.

The SARS-Cov2 pandemic has brought unexpected situations to parturient and puerperal women. Admission and hospitalization rules restricted contact and interaction. Labor was sometimes experienced in isolation or with restrictions on companionship. Returning home without the possibility of interactions with other new mothers and without puerperal recovery classes9. These contingencies perhaps facilitated the onset of PPD. Underdiagnosis may have increased and PPD was, at this stage, a pathology that received little attention10.

In Portuguese women, during confinement, it was found that around 27.5% of the women had high levels of anxiety and depression11. Although the Portuguese population demonstrated good knowledge and positive attitudes to support PPD12, there are no studies in southern Portugal that describe the experience of women themselves in the postpartum period. This suggests that it is important, since in Baixo-Alentejo during the pandemic, there was a high representation of moderate to severe depression in the population13, but PPD was ignored. The aim of the current study is therefore to analyze the prevalence and factors associated with the risk of postpartum depression during the pandemic in puerperal women in Baixo-Alentejo, Portugal.

Methods

Study design and selection of participants

This is a cross-sectional study carried out in a clinical setting among women in the puerperal phase. The questionnaire was distributed online using the Google-forms platform. The estimated completion time was 15 min.

Sample size calculation

The sample was a convenience sample. The sample size was calculated a priori, online (Calculator.net: https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html), based on the number of births that took place in 2021 (i.e. 1006 births), in the maternity ward of the hospital that serves the Baixo-Alentejo region, in the south of Portugal. Thus, with a margin of error of 5%, a 95% confidence interval and a proportion of 23.2%, at cut-off ≥ 10, according to a study at the region center of Portugal 14, the minimum estimated sample was 215 participants. An additional 20% was added to this calculation for possible losses15 estimating 258 cases. However, given the low response rate in a study on the same subject 16, it was decided to increase the increase to 30%, estimating to contact a total of 280 women, as potential participants.

Study recruitment

The inclusion criteria were as follows 1) proficiency in spoken and written Portuguese, 2) age 16 or over, 3) between 28 and 42 days postpartum, 4) means of contact via the Internet. The exclusion criteria were 1) multiple pregnancy, 2) gestational age < 37 weeks, 3) suffering from a pathology prior to pregnancy.

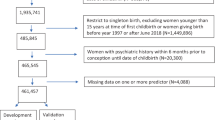

Recruitment began with the potential participants between the 3rd and 6th day postpartum, at the Health Center on the date of the sample collection for the National Neonatal Screening Program, or alternatively around 10–15 days postpartum, at the time of the newborns first appointment at the Health Center. During this first contact, the potential participant was informed about the study and invited to take part. If she agreed, the purpose of the study was explained to her orally. Her cell phone number was collected from her file and permission was asked to contact her after 28 days postpartum. The second contact was made by telephone, sending a message reminding people of the study and asking for permission to call the next day (561 messages sent). If there was a reply to the message sent (47 cases without a reply), a phone call was made, reminding them of the study and informing them of the link they should access to answer the questionnaire (514 messages were sent with the link). Of the potential 514 participants who answered the phone and said they would take part, 316 responded. It should be noted that contacts were abandoned when, after three phone messages in the same week, they didn’t respond to the second contact. Questionnaires with 10% or more unanswered questions were eliminated, as statistical analysis tends to be biased by this proportion16. The sample consisted of 301 cases. Considering concrete and real access to women who had given birth (n = 514) and complete responses (n = 301), the response rate was 58.56 (Fig. 1, with the support of software Lucidchart). The data was collected between January 2022 and January 2023.

The response rate of about 59% was satisfactory. Perhaps pre-notification contributed to greater success, compared to similar studies where the rate was around 60%16.

Study instrument

The questionnaire had six sections. The first section dealt with socio-demographic data, with five questions (categorical variables: nationality, marital status, schooling; discrete variables: age). The second section dealt with preparation for motherhood, with three dichotomous “yes”/“no” categorical variables (pregnancy planning, pregnancy complications, attendance at prenatal classes). The third section focused on childbirth and postpartum data. Information was collected using three polychotomous variables (type of delivery, technician who assisted during the expulsive period of the Labor and a companion during the Labor) and four dichotomous variables, with “yes” and “no” categories (ability to control oneself during the Labor, feeling strong during the Labor, feeling afraid during the Labor and support from the nurses during the Labor). In the fourth section, the questions relating to newborns included assigned sex (male/female) and dichotomous categorical “yes”/“no” questions (skin-to-skin contact, breastfeeding in the first hour of life and breastfeeding difficulties). This section also considered two categorical variables (type of food given to the newborn in the maternity ward, type of food given to the newborn at the time of answering the questionnaire) and a continuous variable (newborn birth weight in grams), which was categorized later. Section five asked, using a visual analogue scale scored from 0 (absence of the attribute) to 100 (maximum of the attribute), 1) the level of security felt by the parturient, as well as 2) the level of pain, both variables contextualized during labor. Finally, the sixth section presented the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) in the Portuguese version applied in the clinic 6,8 which is the criterion variable or explained variable of the current study.

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) used in the questionnaire is the Portuguese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) 6,17. It is an instrument that has been around for 30 years and has been translated and validated in more than 60 languages7,8. For the Portuguese context, it was validated in 1996 for portuguese mothers 8,18,19. Its application has been recommended by the DGH since 2005 subsequently reinforced6. It is a screening measure used in the clinic and does not require permission from any entity or author.

The EPDS is a 10-item self-completion instrument that uses a 0–3 point scale to access the symptoms recognized by the postpartum woman. After reversing items 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10, the sum of the scores is obtained, which reveals the risk of postpartum depression, but does not diagnose the severity of the condition. In the current study, taking guidance from the literature and clinical guidelines6,8,14,20, although the score ≥ 12 is mentioned, as this is the cut-off initially established by the DGH the cut-off point ≥ 10 was adopted for the statistical analysis5,7,8. The reliability of the EPDS, observed through the Cronbach’s α coefficient, was good21, with a value of 0.845, similar to a previous study in Portugal14.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS software (version 28, with a user license from the University of Évora, Portugal). When sorting the data, we ensured that there were no missing cases, obtaining 301 participants with complete answers.

In the univariate analysis, continuous variables were analyzed with measures of central tendency and dispersion and categorical variables with frequencies and proportions. Predictors were screened to identify potential covariates to include in the model22,23.

The EPDS, a criterion variable for recording the prevalence of risk of PPD, after reversing the items indicated, was observed from the perspective of two cut-off points 6,8,17.The cut-off point ≥ 12 is referred to occasionally and the analysis of the sample continued based on the cut-off point ≥ 10, based on literature orientation7,8.

In the bivariate analysis, considering the cut-off point ≥ 10, the chi-square test was applied to observe the relationship between the risk of PPD and the categorical variables. The relationship between the risk of PPD and the continuous variables was observed using the Mann–Whitney test.

In the multivariate analysis, in order to identify the factors associated with the risk of PPD (i.e. 0 = no, 1 = yes), a binary logistic regression (BLR) was carried out, taking into account the relationship that the EPDS had with the variables observed in the bivariate analysis. Potential predictors were those variables whose p-value ≤ 0.2521,23,24,25.

In the regression, although the Forward Stepwise and Backward Stepwise methods were observed, the Enter method was used to identify the best multivariate model21,24. The regression coefficient and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were determined for each predictor.

In the RLB model, it was decided to keep the outlier, as it was below 2.5821 and mirrored the case that does not fit into a general pattern of around 300 women. In fact, such outliers represent natural variations, exceptional cases in the observed population.

The choice to analyze the data using RLB was due to its advantages, as it has fewer restrictions than other techniques. It does not require the predictor variables to have a normal distribution or a linear relationship with the criterion variable, nor does it require homogeneity of variance in the predictor variables21.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current study was carried out under the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki26. All methods were performed according to the relevant guidelines and regulations. Following the recruitment process, informed consent was requested on the Google Platform. The potential respondent could only progress to the questions and answer the questionnaire if she had ticked “yes” after reading the following sentence “If you have understood the above, if you feel you have been informed and if you agree to participate, please click ‘yes’ in the box below”. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Évora. It received a positive opinion on January 3, 2022, with registration number 22005.

Results

The participants responded on average around the 10th week postpartum (M = 9.90; SD = 4.19), ranging from 4.02 (4 weeks and 1 day) to 22.35 (approximately 5th month postpartum). The majority of responses were received between 4 and 11.9 weeks (n = 227; 75.4%).

Sociodemographic characteristics

The 301 participants had an average age of 31.35 years (SD = 5.90), with a range of 16–47 years, with 10 (3.3%) under the age of 20. The majority were Portuguese (n = 271; 90.0%). The majority were living in a formal marriage or de facto union (n = 227; 75.4%), with the predominant level of education being secondary school (i.e. 12th grade; n = 126; 41.9%).

Characteristics of the pregnancy and labor experience

The majority of pregnancies were planned (n = 185; 61.5%) and had no complications (n = 242; 80.4%), with 157 (52.2%) having attended antenatal classes (AC).

The most common type of delivery was eutocic (n = 139; 46.2%), but in 58 women (19.3%) forceps/suction cups were used. Urgent caesarean section occurred in 61 (20.3%) and elective caesarean section in 43 (14.3%). Most women reported not having a companion during the first stage of labor (n = 177; 58.8%) and 238 (79.1%) acknowledged the support of the nurses throughout labor. Of the 197 women who gave birth vaginally, the majority were assisted by a doctor (n = 114; 57.9%) and 83 (42.1%) were assisted by nurses. Immediately after fetal expulsion, the majority had skin-to-skin contact with the NB (n = 184; 61.1%) and breastfed within the first hour of life (n = 195; 64.8%). In 199 cases (64.8%) no difficulties were reported with breastfeeding.

Most of the newborns (n = 271; 90%) were of normal weight (i.e. 2,500—3,999 kg) and female (n = 153; 50.8%). The majority of these children were exclusively breastfed in the maternity ward (n = 197; 65.4%), falling to 61.5% (n = 185) at the time of answering the questionnaire at home (Table 1).

The average time between admission to the hospital and delivery was 12.63 h (SD = 11.71), ranging from 15 min to 101 h (4.2 days).

On a scale of 0–100, the participants described feelings of safety during labor with an average of 75.40 (SD = 25.87). The level of pain during Labor varied between 0 and 100, with an average of 56.06 (SD = 35.89).

Risk of postpartum depression

Regarding EDPS, the frequencies and proportions are shown in Table 2

The sum of the EPDS ranged from 1 to 24 (M = 7.149; SD = 4.30).

There were 49 women (16.27%) at the cut-off point ≥ 12. Item 10 was marked positively in 16 cases (5.3%). Taking into account the 49 cases with a score ≥ 12 and the cases in which item 10 exists in the current sample there are 57 women at risk, i.e. a prevalence of 19% ([57/301] * 100 = 18.93%).

However, following the current study, the cut-off point is ≥ 10. This is due to the authors’ recommendation that “a cut-off of 9/10 was likely to detect almost all cases of depression, with few false negatives. This cut-off score is particularly useful in a research project in which the EPDS is the only measure used or when it is used as a first-stage screening scale to identify possible depression” (p.21)8. In this interpretation, the frequency of risk of PPD is 83 cases, with a point prevalence of risk of PPD of 27.57% ([83/301] *100). Category 1 was assigned to women at risk (score ≥ 10) and category 0 to those whose score did not reach 10. The analysis continued considering the cut-off of 10.

Bivariate analysis of categorical variables against the EPDS criterion variable

The relationship between the EPDS (i.e. without risk = 0; with risk = 1) and the categorical variables was analyzed using χ2 tests, previously safeguarding the Cochran criteria (expected values > 5; n ≥ 40)21.

With regard to the sociodemographic variables, there was no statistically significant relationship with the risk of PPD, with p-value > 0.05 for nationality and level of education.

In the variables of the “preparation for motherhood” group, there was a statistically significant relationship between the pregnancy planning variable and the risk of PPD (p = 0.001). In the other variables in this group, there was no statistically significant association (p-value > 0.05).

In the variables of the “labor and postpartum experience” group, there was a statistically significant relationship between whether the woman felt strong during labor (p < 0.001), fear (p < 0.001) and self-control (p = 0.025).

With regard to the “accompaniment during labor” variables, there was a statistically significant relationship between the risk of PPD and the support figure (p = 0.002) and the nurses’ support (p = 0.036). Finally, the variables relating to how the newborn was fed showed no association with the risk of PPD and all the p-values, except for the variable “breastfeeding difficulties” (p = 0.119), were higher than 0.250 (Table 3).

The variable “food given to the newborn in the maternity ward” was not subject to bivariate analysis because one of the cells did not meet Cochran’s criterion21.

Bivariate analysis of continuous and discrete variables in relation to the EPDS criterion variable

A bivariate analysis using the Mann–Whitney test showed that age had no influence on the risk of PPD. With regard to the two visual analog scales reported during labor, there was a statistically significant relationship only with the level of safety felt during labor (Table 4).

BLR analysis of the risk of PPD and its influencing factors

No multicollinearity was found, with tolerance values between 0.563 and 0.957 (T > 0.100) and VIF between 1.045 and 1.777 (VIF < 10).

We moved on to the BLR, inserting nine potential predictor variables, eight of which were categorical and one continuous, according to the previous bivariate analysis. In the current RLB, the categorical variables have category 0 (first) as a reference.

Decision on the method to be used in the BLR—enter or stepwise

Before deciding on the method of logistic regression analysis, a step-by-step approach was taken, applying the Forward Stepwise and the Backward Stepwise methods (supplementary table 1 and supplementary table 2). The stepwise method is an exploratory method and the decision on which variables to include is made using statistical criteria27. It is a method normally applied to large samples. However, this method can choose uncomfortable variables instead of true variables28 Therefore, we opted for the enter method, the standard method, which inserts all the independent variables simultaneously, since there were no candidate covariates, more or less significant, to start the statistical process.

Establishing the cut-off point for the risk of PPD

Given that the literature invoked different cut-off points for PPD, the relationship between the predictor variables identified in the bivariate analysis and the Risk of PPD was observed, considering the cut-off point for the EPDS ≥ 12. However, the cut-off point ≥ 12 was abandoned, as the sensitivity was very low (22.4%), suggesting that false negatives could be hidden (Supplementary table 3).

RLB analysis using the enter method and EPDS cut-off ≥ 10

The logistic regression was continued with the Enter method and a cut-off score ≥ 10 was considered. This decision was based on the fact that false negatives have serious adverse consequences for both women and children 27. Since there was no significant multicollinearity between the predictors, the Enter method would lead to stable and reliable parameter estimates, making it easier to interpret the individual effects of each predictor 21,24.

In the RLB analysis, using the Enter21, the model was found to be statistically significant, as revealed by the 2nd stage Omnibus tests of model coefficients (\({\upchi }_{(10)}^{2}\)=81.582, p < 0.001). The model explained 34.3% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in the risk of PPD, although the log-likelihood statistic is high (− 2 Log likelihood = 272.931). About 70% of cases (77.1%) were correctly classified. According to the Hosmer and Lemeshow test, the model is adjusted (p = 0.055).

Analyzing the variables included in the model and keeping the other independent variables constant, three factors were significantly associated with the risk of PPD: 1) Level of safety during labor, 2) Pregnancy planning and 3) Figure of a companion during labor.

The OR value for the variable “level of safety during labor” (adj OR = 0.958, 95% CI 0.942–0.974) suggests that for each incremental unit, the chances of PPD decrease by about 4.2% ([0.958–1]*100 = 4.2).

The second predictor variable, “pregnancy planning”, has a negative Beta value (B = − 1.568, 95% CI 0.109–0.397), which is a protective factor against PPD. The OR coefficient (Exp(B) = 0.209) shows that the chance of PPD in women who have planned their pregnancy is lower than in those who have not, as its value is less than one. On the other hand, having used the “first” criterion in the categorical variables at the time of the BLR, the ratio 1/Exp(B) (1/0.209 = 4.78) means that women who have not planned their pregnancy are 4.78 more likely to have PPD.

The third predictor, related to the companion figure “Family-Accompanying Person”, in relation to the reference category “Nobody-Accompanying Person”, shows a negative Beta value (B = − 1.074, 95% CI 0.163–0.715). Thus, the risk of PPD is higher in situations where the woman had no one to accompany her, compared to women who had a relative. The chance of women without a companion having PPD is 2.92 times higher compared to women who were accompanied by a relative (1/exp(B) = 1/0.342 = 2.92) (Table 5).

The model has one outlier (case 258), whose standardized residuals were 2,503.

The sensitivity analysis showed that the model correctly classifies 33 cases (true positives) and misses 50 cases (false negatives). In other words, it correctly classifies 39.8% of cases. On the other hand, the specificity analysis shows that it correctly classifies 91.3% of the cases that have no risk of PPD (true negatives). The weighted average was 77.1% (Table 6).

Discussion

This discussion, in order to substantiate some aspects and due to the volume of guidelines produced by the DGH and the Portuguese Government, draws on gray literature, presented in Supplementary Table 4.

Considering sociodemographic characteristics, the average age of the participants coincides with the average age of women who were mothers in 2022 in the Baixo-Alentejo region (31.4 years in 2022). This indicator has been above 30 in this region since 200928. In the nationality variable, 10% of foreign women are represented, corresponding to the current increase in social and labor mobility. In 2022, the contribution of foreign women to the birth rate was 10.1% in Baixo-Alentejo29. Regarding educational qualifications, the representation of secondary education in the current study is close to that of women in this district at the time of the 2021 Census (41.9% versus 40.99%)30. The formal marriage or de facto union show that the vast majority recognize a conventional parenting model.

Considering the characteristics of pregnancy experience, the participants’ statements about planning their last pregnancy are at odds with the advances made by Portuguese society since the 1980s. Although unplanned pregnancies and births continue to occur in Portugal, the number of cases has decreased since the 1990s, from 39.4 to 25% in the 2015–2019 period31.

Attendance at AC suggests that some of the pregnant women were looking for training in motherhood skills. It is in accordance with Portuguese law which also contributes to this (Supplementary Table 4: Reference 1). At the same time, the results reflect the crisis imposed by the pandemic. In fact, the end of the alert status in Portugal at the end of September 2022 (Supplementary Table 4: Reference 2) did not immediately bring the availability of face-to-face AC.

Considering the labor experience, the period of time between the parturient’s admission and delivery, although averaging 12.63 h, varied widely. Anxiety specific to childbirth is a major factor in late pregnancy32, perhaps aggravated by the pandemic, although the DGH guidelines were intended to guide and reassure (Supplementary Table 4: Reference 3).

The presence of a companion during the PT, as reported by the participants, is in line with other studies where poor adherence has been recognized, with the region of the country having the lowest representation9. Perhaps the changes to the DGH guidelines (Supplementary Table 4: Reference 4) have created some confusion in interpretation.

The representation of vaginal deliveries is similar to the data present in the year 2022 in the DGH information (65.4% versus 67.3%)33. On the other hand, cases of forceps/ventilation and caesarean sections are very high, suggesting Odent’s question as to whether women are losing the ability to give birth34. These results concur with other studies35, showing the medicalization of labour, and a substantial increase in cesarean deliveries in Portugal10.

The representation of skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding was low, in agreement with literature, which recognize that the region has the lowest rates in the country9. The effect of the pandemic was felt in the support expected/offered during the parturient/midwife interaction36. Skin-to-skin contact and early breastfeeding in the postpartum period, as proposed by the DGH during the pandemic, perhaps had some resolutions that were seen as justifiable and safe for the time, which were later clarified (Supplementary Table 4: Reference 5). It was a difficult time, with information not always assimilated in the best way.

The risk of PPD is high in this population, with a prevalence of 27.57% at the cutoff point ≥ 10, which is close to Brazil’s results37,38, Spain39 and in other countries40. For organic and social reasons, or a combination of these factors, puerperal susceptibility is higher.

The context in which PPD is considered in Portugal is controversial. On the one hand, the National Health Council Report on Mental Health41, relied on the Minsk Declaration to identify PPD as a neglected problem (item 5.5, page 7). In a positive light, the same report warns of the DGH guidelines and exemplifies the inclusion of PPD prevention in the AC41. Meanwhile, the reference to depression in recent Portuguese guidelines is residual (page 6, item 20). (Supplementary Table 4: Reference 4). On the other hand, considering environmental factors that can influence depressive conditions42, the Alentejo region, has the highest suicide rates compared to the national average (17.4 versus 9.9/100,000 inhab—Mortality rate due to intentional self-harm [suicide] per 100.000 inhabitants) 43. Monitoring these women is essential, as morbidity tends to last for years42, with implications for individual and family development, often leading to self-destructive behavior44.

It is particularly relevant that in item 10, sixteen women (5.3%) recognized self-harm thoughts (SHTs) in themselves. The results corroborate the 6.2% in Denmark44. The current results also refer to coexisting factors in the environment, corroborating the 5% of women with SHTs in Finland compared to 15% in India42. Reflecting on the results of item 10 of the EPDS, there is perhaps a notion of the invisibility of risk in health policies and thus the invisibility of local women. The collection of data through the EPDS by the midwife and subsequent referral, given the greater contact she has with the woman, is a suggestion45, perhaps to be implemented universally in the country.

Discussing the BLR analysis of the risk of PPD and its associated factors, the screening of predictors was carried out in order to identify potential covariates to include in the model 22,23. The univariate analysis with potential predictors, preceding logistic regression, was useful, corroborating previous studies 46. The cut-off point for the significance of the predictors is somewhat liberal (p-value < 0.10 or < 0.25 or < 0.157)24,25. The p-value limit < 0.05 is often used, but this can lead to important variables being removed due to stochastic variability (i.e. the occurrence of predictors that are uncertain and unpredictable) 25. The threshold of 0.25 was used because, although it is a less rigorous criterion it is a strategy that reduces the failure to detect a real effect. This avoids the exclusion of potentially important variables, which by being disregarded, restrict the possibility of finding an effect that does exist.

As well as there being a gap in the predictors of PPD risk in the local context, there was some uncertainty about which variables to include in the regression model. In fact, previous studies which include Portugal have mainly looked at the association of the risk of PPD with political and economic factors, maternal and infant mortality and sociodemographic characteristics 47.

The Enter method was preferred because there was no literature on local research, corroborating literature46. On the other hand, the stepwise approach is influenced by random variations in the data and may not provide replicable data if the model is run later with the same sample 21.

The findings of this study indicate that a poor sense of security during labor is a predictor of PPD, corroborating the importance of the subjective safety of the parturient for the success of the childbirth process48. Insecurity generates fear, unease and anxiety, preventing the woman in labor from achieving an Altered State of Consciousness (ASC). If a woman does not feel safe or protected during labor, catecholamine levels rise and labor slows down or stops49. A quiet and private environment, dark, without noise, without unnecessary interventions, it will lead to the induction of ASC, which is a consequence of transient hypofrontality34,49. Lite touch communicates safety, attention and does not trigger the production of cortisol and catecholamines50.

ASC, as a temporary state of reduced frontal cortex activity, leaves women vulnerable. This leads us to interpret the predictor “presence of a family member” as a protective factor for the risk of PPD. Recent studies have identified a positive association51 and the WHO even recommends the presence of a family companion during labor45. Faced with an unfamiliar hospital environment, with people she has never seen before, with unfamiliar sounds and smells, but where one of the most significant moments of her life will take place, the presence of a familiar figure will be valued. It should also be borne in mind that the participants’ labor took place during the pandemic, in which, if the woman was infected, she would not have a companion and would be assisted by a professional wearing personal protective equipment (PPE). In other words, a major barrier to the tangible support that touch can offer (Supplementary Table 4: Reference 6).

The desire for motherhood and the desire to have a child do not always coincide, resulting in unplanned pregnancies, which lead to depressive states52. This is described in a meta-analysis, which found a significant association between unwanted pregnancy and the risk of PPD53. Perhaps greater investment in preconception care, with increased interaction between patients and professionals, could lead to better outcomes and improved access to voluntary termination of pregnancy.

A progressive movement to integrate PPD screening is underway54. There is an urgent need for clinical practice to be transformed, providing the care repeatedly recommended by WHO45,55,56, the DGH6, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 57. Light may be shed on the risk of PPD and its clinical practices through the “Women Choose Health” project, announced by the SNS58.

In the current study, the percentage of women at risk of PPD, considering the cut-off point ≥ 10, proved to be high (n = 83, 27.5% in the sample of 301 cases). However, if the specificity was high (91.3%), i.e. the ability to correctly classify postpartum women who really had no risk of PPD (true negatives), a low sensitivity (true positives) was expected, but not as low as 39.8%. The cut-off in the EDPS ≥ 10 was used on purpose, as the scarce local knowledge about the risk of PPD was intended to avoid false negatives and identify the majority of women at risk.. However, the sensitivity of 39.8% is lower than that observed by a meta-analysis which recorded a cut-off point ≥ 10 of around 77%5. Despite the limitations, the ≥ 10 cutoff bridge nevertheless proved to be useful for local studies, as it provided some information in the face of a strong gap in knowledge.

Limitations

Since the sample was a convenience sample, the results cannot be generalized. The results for the marital status variable may have been biased by the incorrect way the question was asked. It would have been more appropriate to say “not cohabiting with husband/partner”. For reasons of inaccessibility, it was not possible to compare the participant group with the non-respondent group in terms of differences in sociodemographic and clinical variables. This could lead to a bias in the sample and more depressed cases could be over-represented or even not represented at all.

Conclusion

In Portugal, there is a lack of studies on the subject in the south of the country, particularly in the Alentejo. The current study aims to respond to this regional gap.

In terms of associated factors, pregnancy planning is a robust predictor of PPD, so it will be important to invest in health care that leads women to have more skills to deal with fertility. It’s also important to set up puerperal follow-up programs with a mixed team (psychologist, social worker, nurse, doctor) to ensure that the case is flagged and that progress is assessed. In fact, ignored or untreated PPD has a negative impact on the dyad. It leaves significant sequelae on the child’s development and women health.

Perhaps the universal application of screening tools to postpartum women, longer postpartum follow-up programs, could facilitate help-seeking and more positive maternity experiences. Nurses and midwives are the first line of the multidisciplinary team to continuously monitor women during the pregnancy-puerperium phase and are a valuable element in assessing the risk of PPD.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

WHO. WHO recommendations: Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience: web annex; evidence base. (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2018).

APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™, 5th ed. (American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., 2013).

Brum, E. Depressão pós-parto: discutindo o critério temporal do diagnóstico. Cadernos de Pós-Graduação em Distúrbios do Desenvolvimento 17, https://doi.org/10.5935/cadernosdisturbios.v17n2p92-100 (2017).

Tanuma-Takahashi, A. et al. Antenatal screening timeline and cutoff scores of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for predicting postpartum depressive symptoms in healthy women: A prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 527. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04740-w (2022).

Levis, B., Negeri, Z., Sun, Y., Benedetti, A. & Thombs, B. D. Accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for screening to detect major depression among pregnant and postpartum women: Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ 371, m4022. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4022 (2020).

DGS. Programa Nacional para a Vigilância da Gravidez de Baixo Risco. (Direção Geral de Saúde, 2015).

Cox, J. in Br J Psychiatry Vol. 214 127–129 (2019).

Cox, J., Holden, J. & Henshaw, C. Perinatal Mental Health. 2nd edn, 213 (The Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2014).

Costa, R. et al. Regional differences in the quality of maternal and neonatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal: Results from the IMAgiNE EURO study. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 159(Suppl 1), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.14507 (2022).

Borges Charepe, N. et al. One year of COVID-19 in pregnancy: A national wide collaborative study. Acta Med. Port. 35, 357–366. https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.16574 (2022).

Fernandes, D. V., Canavarro, M. C. & Moreira, H. Postpartum during COVID-19 pandemic: Portuguese mothers’ mental health, mindful parenting, and mother-infant bonding. J. Clin. Psychol. 77, 1997–2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23130 (2021).

Branquinho, M., Canavarro, M. C. & Fonseca, A. Postpartum depression in the Portuguese population: The role of knowledge, attitudes and help-seeking propensity in intention to recommend professional help-seeking. Community Ment. Health J. 56, 1436–1448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00587-7 (2020).

INSA. Relatório final: SM-COVID19 - Saúde mental em tempos de pandemia. (Instituto Nacional de Saúde Doutor Ricardo Jorge, 2020).

Alves, S., Fonseca, A., Canavarro, M. C. & Pereira, M. Predictive validity of the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised (PDPI-R): A longitudinal study with Portuguese women. Midwifery 69, 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2018.11.006 (2019).

Suresh, K. & Chandrashekara, S. Sample size estimation and power analysis for clinical research studies. J. Human Reproduct. Sci. 5, 7–13. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-1208.97779 (2012).

Ostacoli, L. et al. Psychosocial factors associated with postpartum psychological distress during the Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 703. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03399-5 (2020).

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M. & Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry. 150, 782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782 (1987).

Augusto, A., Kumar, R., Calheiros, J. M., Matos, E. & Figueiredo, E. Post-natal depression in an urban area of Portugal: Comparison of childbearing women and matched controls. Psychol. Med. 26, 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700033778 (1996).

Areias, M. E., Kumar, R., Barros, H. & Figueiredo, E. Comparative incidence of depression in women and men, during pregnancy and after childbirth Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in Portuguese mothers. Br. J. Psychiatry 169, 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.169.1.30 (1996).

Fonseca, A. et al. Treatment options and their uptake among women with symptoms of perinatal depression: Exploratory study in Norway and Portugal. BJPsych Open 9, e77. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.56 (2023).

Field, A. P. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. (SAGE, 2018).

Grant, S. W., Hickey, G. L. & Head, S. J. Statistical primer: Multivariable regression considerations and pitfalls†. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 55, 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezy403 (2019).

Bursac, Z., Gauss, C. H., Williams, D. K. & Hosmer, D. W. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol. Med. 3, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0473-3-17 (2008).

Ranganathan, P., Pramesh, C. S. & Aggarwal, R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Logistic regression. Perspect. Clin. Res. 8, 148–151. https://doi.org/10.4103/picr.PICR_87_17 (2017).

Heinze, G. & Dunkler, D. Five myths about variable selection. Transpl. Int. 30, 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/tri.12895 (2017).

WMA. Medical Ethics Manual. 3rd edn, 73 (World Health Communication Associates, 2015).

Djatche Miafo, J. et al. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale and prevalence of depression among adolescent mothers in a Cameroonian context. Sci. Rep. 14, 30670. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79370-7 (2024).

Pordata. Idade média da mãe ao nascimento de um filho. Ano 2022, <https://www.pordata.pt/db/municipios/ambiente+de+consulta/tabela> (2024).

Pordata. Nados-vivos de mães residentes em Portugal. Total e por nacionalidade da mãe, <https://www.pordata.pt/municipios/nados+vivos+de+maes+residentes+em+portugal+total+e+por+nacionalidade+da+mae-718> (2024).

INE. Proporção da população residente com pelo menos o ensino secundário completo (%) por Local de residência à data dos Censos [2021] (NUTS - 2013) e sexo, https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&indOcorrCod=0011660&contexto=bd&selTab=tab2 (2022).

Guttmacher Institute. Unintended pregnancy and abortion. Portugal profile, <https://www.guttmacher.org/regions/europe/portugal> (2024).

Ataman, H. & Tuncer, M. The effect of COVID-19 fear on prenatal distress and childbirth preference in primipara. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. (1992) 69, e20221302. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.20221302 (2023).

SNS. Partos e Cesarianas nos Cuidados de Saúde Hospitalares, https://transparencia.sns.gov.pt/explore/dataset/partos-e-cesarianas/table/?flg=pt-pt&disjunctive.regiao&disjunctive.instituicao&sort=tempo&refine.regiao=Regi%C3%A3o+de+Sa%C3%BAde+do+Alentejo&refine.instituicao=Unidade+Local+de+Sa%C3%BAde+do+Baixo+Alentejo,+EPE&refine.tempo=2022 (2022).

Odent, M. Do we need midwives? , (Pinter & Martin, 2015).

Sabetghadam, S., Keramat, A., Goli, S., Malary, M. & Rezaie Chamani, S. (2022) Assessment of medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth in low-risk pregnancies: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery. 10, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.30476/ijcbnm.2021.90292.1686 .

Padez Vieira, F. et al. Depression among Portuguese pregnant women during COVID-19 lockdown: A cross sectional study. Maternal Child Health J. 26, 1779–1789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-022-03466-7 (2022).

Lutz, B. H. et al. Folic acid supplementation during pregnancy and postpartum depressive symptoms. Rev. Saude Publica 57, 76. https://doi.org/10.11606/s1518-8787.2023057004962 (2023).

Figueiredo, F. P. et al. Postpartum depression screening by telephone: A good alternative for public health and research. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 18, 547–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0480-1 (2015).

Míguez, M. C. & Vázquez, M. B. Prevalence of postpartum major depression and depressive symptoms in Spanish women: A longitudinal study up to 1 year postpartum. Midwifery 126, 103808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2023.103808 (2023).

Lyubenova, A. et al. Depression prevalence based on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale compared to Structured Clinical Interview for DSM DIsorders classification: Systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 30, e1860. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1860 (2021).

CNS. Sem mais tempo a perder. Saude mental em Portugal: um desafio para a próxima década. (Conselho Nacional da Saude, 2019).

Iliadis, S. I. et al. Self-harm thoughts postpartum as a marker for long-term morbidity. Front. Public Health 6, 34. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00034 (2018).

INE. Mortality rate due to intentional self-harm (suicide) per 100.000 inhabitants (No.) by Place of residence (NUTS - 2013). www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&indOcorrCod=0003736&contexto=bd&selTab=tab2&xlang=en (2022).

Ayre, K. et al. Self-harm in women with postpartum mental disorders. Psychol. Med. 50, 1563–1569. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719001661 (2020).

WHO. WHO recommendations on maternal care for a positive postnatal experience. (World Health Organization, 2022).

Hazra, A. & Gogtay, N. Biostatistics series module 10: Brief overview of multivariate methods. Indian J. Dermatol. 62, 358–366. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijd.IJD_296_17 (2017).

Hahn-Holbrook, J., Cornwell-Hinrichs, T. & Anaya, I. Economic and health predictors of national postpartum depression prevalence: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 291 studies from 56 countries. Front. Psych. 8, 248 (2018).

Lyberg, A., Dahl, B., Haruna, M., Takegata, M. & Severinsson, E. Links between patient safety and fear of childbirth-A meta-study of qualitative research. Nurs. Open 6, 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.186 (2019).

Lothian, J. A. Do not disturb: the importance of privacy in labor. J. Perinat. Educ. 13, 4–6. https://doi.org/10.1624/105812404x1707 (2004).

Yang, W. et al. Effect of lite touch on the anxiety of low-risk pregnant women in the latent phase of childbirth: a randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychol. 15 (2024).

Lin, Y. H., Chen, C. P., Sun, F. J. & Chen, C. Y. Risk and protective factors related to immediate postpartum depression in a baby-friendly hospital of Taiwan. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 61, 977–983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2022.08.004 (2022).

Carlander, A. et al. Unplanned pregnancy and the association with maternal health and pregnancy outcomes: A Swedish cohort study. PLoS ONE 18, e0286052. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286052 (2023).

Qiu, X., Zhang, S., Sun, X., Li, H. & Wang, D. Unintended pregnancy and postpartum depression: A meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. J. Psychosom. Res. 138, 110259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110259 (2020).

O’Hara, M. W. & McCabe, J. E. Postpartum depression: Current status and future directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 379–407. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185612 (2013).

WHO. Thinking Healthy. A manual for psychosocial management of perinatal depression. (World Health Organization, 2015).

WHO. Guide for integration of perinatal mental health in maternal and child health services. (World Health Organization, 2022).

ACOG. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 757: Screening for Perinatal Depression. Obstetrics & Gynecology 132 (2018).

SNS. Projeto quer promover a saúde mental da mulher na gravidez e pós-parto, <https://saudemental.min-saude.pt/projecto-quer-promover-a-saude-mental-da-mulher-na-gravidez-e-pos-parto/> (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank to all women who agreed to participate in the study

Funding

This work is funded by national funds through the Foundation for Science and Technology, under the project UIDP/04923/2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S., O.Z. and M.S-S. contributed to the conception. S.S. and M.S-S. contributed to the design of the study and funding acquisition. S.S., U.S. collected data, U.S. S.S. and M.S-S., contributed to the manage the data collection and commented on the manuscript. M.S-S., O.Z. and M.B. conducted statistical analysis of data and drafed the manuscript. O.Z., M.B. and U.S. commented on the manuscript. All the authors approved the final manuscript as submitted, agreed to be accoutable for all aspects of the work and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, S., Barros, M., Zangão, O. et al. Prevalence and contributing factors of postpartum depression risk during the pandemic among women living in Baixo Alentejo at Portugal. Sci Rep 15, 35420 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17949-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17949-4