Abstract

Understanding the relationship between molecular structure and physicochemical properties is a central problem in mathematical chemistry and molecular informatics. Among the many topological descriptors used for this purpose, Zagreb indices play a significant role due to their proven relevance in quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) studies. Motivated by the need for structural insight into molecules modeled as trees, this work focuses on deriving lower bounds for the first and second Zagreb indices of trees with a fixed total domination number. By analyzing the structural properties of such trees, we establish new inequalities that highlight the interplay between domination parameters and molecular descriptors. To validate their practical relevance, we apply the derived bounds in a QSPR context, specifically examining their correlation with key physicochemical properties of alkanes. The statistical analysis reveals strong predictive capability, with near-to-unity correlation coefficients between the computed bounds and experimental data. These results demonstrate the potential of domination-theoretic methods in advancing predictive modeling in chemical graph theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological indices serve as fundamental tools in mathematical chemistry, enabling the characterization of molecular structures and the prediction of their physicochemical properties. For this purpose, chemical graphs \(G=(V,E)\) were constructed from the molecular structures, where vertices (V) represent the major non-hydrogen atoms, and edges (E) denote bonds without distinguishing between single and double types, in accordance with standard conventions1. Among the many topological descriptors, the Zagreb indices2 are particularly well-established and are defined for a simple, connected graph G as follows:

where \(d_\alpha\) denotes the number of vertices in \(N(\alpha )\), the set of vertices adjacent to \(\alpha\). The diameter of G, denoted as d, measures the maximum distance between any pair of vertices in G.

A tree \(\mathscr {T}\) is a connected acyclic graph, and the total domination number \(\gamma _t(G)\) is the minimum size of a set \(\mathscr {D}\) (denoted as TDS) in V(G) such that every vertex in G has a neighbor in \(\mathscr {D}\)3. The Zagreb indices provide insights into the degree distribution of a molecular graph, offering a connection to molecular stability and reactivity. In parallel, the total domination number captures aspects of structural regulation within the graph, often associated with molecular branching and interaction patterns. Both descriptors are fundamental in Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling, where they are employed to predict a wide range of physical, chemical, and biological properties based on molecular structure. Their central role in QSPR highlights the need for continued investigation and refinement of these indices to enhance the accuracy and interpretability of predictive models.

The study of graph-based molecular descriptors continues to attract significant attention, particularly through recent investigations into extremal trees involving geometric-arithmetic and Randić indices4,5, exponential augmented Zagreb indices6, and their applications in structure-property relationships via topological indices7. Notably, a growing body of work has examined the relationships between domination-related graph parameters and various well-known indices such as Randić8,9, geometric-arithmetic10, Sombor11 and Zagreb12. Motivated by these findings, the present work introduces a new lower bound for the Zagreb indices of trees based on their total domination number, thereby extending previously known upper bound results12. Furthermore, the predictive capability of this bound is assessed using a dataset of 15 unbranched alkanes, and linear regression models are developed to demonstrate its relevance in QSPR studies.

For definitions of graph-theoretic notations and terminology not explicitly provided in this work, the reader is referred to13. For topics related to domination in graphs, see14, and for further details on Zagreb indices, refer to15,16. The approach underlying the main results is based on the framework presented in10.

Preliminary concepts

Let \(\mathscr {T}_{n,\gamma _t}\) denote the set of trees with n vertices and total domination number \(\gamma _t\). Denote \(\zeta _1(\alpha ,\beta )=\alpha + \beta\) and \(\zeta _2(\alpha ,\beta )=\alpha \beta\). The following results can be readily observed.

Lemma 1

Let \(\mathscr {T}\) be a tree of order \(n \ge 3\). Then

where \(S_n\) and \(P_n\) denote the star and path on n vertices, respectively.

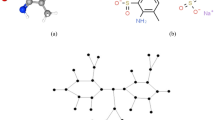

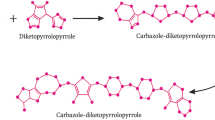

The family of trees \(\mathscr {G}\) is defined recursively as follows10: For each integer \(k \ge 1\), the path graph of order 4k belongs to \(\mathscr {G}\). Furthermore, suppose \(\mathscr {T} \in \mathscr {G}\) contains two vertices \(\alpha _1, \alpha _2 \in V(\mathscr {T})\) satisfying \(N(\alpha _1) = \{\theta _1, \alpha _2\}\), \(N(\alpha _2) = \{\alpha _1, \theta _2\}\), \(d_{\theta _1}=d_{\theta _2}=2\), and \({\alpha _1, \alpha _2}\) is contained in a minimum TDS of \(\mathscr {T}\). Then, for integers \(l_1\) and \(l_2\), let \(P_{4l_1+1}\) and \(P_{4l_2+1}\) be paths of orders \(4l_1+1\) and \(4l_2+1\), respectively. Let \(\eta _1\) and \(\eta _2\) denote pendant vertices of \(P_{4l_1+1}\) and \(P_{4l_2+1}\). The tree obtained by attaching \(P_{4l_1+1}\) and \(P_{4l_2+1}\) to \(\mathscr {T}\) via the edges \(\alpha _1\eta _1\) and \(\alpha _2\eta _2\) is also included in \(\mathscr {G}\) (see Fig. 1, where the dark vertices represent elements of the minimum TDS).

Define \(\mathscr {G}_{n,\gamma _t}\) as the set of all \(\mathscr {T} \in \mathscr {G}\) having n vertices and total domination number \(\gamma _t\). Denote

Lemma 2

\(M_1(\mathscr {T})=\chi _{n(\mathscr {T}), \gamma _t(\mathscr {T})}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T})=\chi '_{n(\mathscr {T}), \gamma _t(\mathscr {T})}\) for each \(\mathscr {T} \in \mathscr {G}_{n,\gamma _t}\).

Proof

Let \(l_p\) represent the count of vertices that have a degree of p. For \(\mathscr {T} \in \mathscr {G}_{n,\gamma _t}\),

Hence, \(l_1=n-2\gamma _t+2\), \(l_2=4\gamma _t-n-2\), and \(l_3=n-2\gamma _t\). Applying these equations to the definitions of \(\mathscr {G}_{n,\gamma _t}\), \(M_1\), and \(M_2\),

\(\square\)

Main results

Lemma 3

Let \(h_1(c)= c^2-7c+14\). Then, \(h_1(c)>0\) whenever \(c \ge 4\).

Proof

Thus, \(h_1(c) \ge h_1(4)=2 > 0\). \(\square\)

Theorem 1 establishes \(\chi _{n(\mathscr {T}), \gamma _t(\mathscr {T})}\) as a lower bound for \(M_1(\mathscr {T})\) and \(\chi '_{n(\mathscr {T}), \gamma _t(\mathscr {T})}\) as a lower bound for \(M_2(\mathscr {T})\), and also identifies the extremal trees achieving these bounds.

Theorem 1

Let \(\mathscr {T} \in \mathscr {T}_{n,\gamma _t}\). The following results are observed.

-

1.

\(M_1(\mathscr {T}) \ge \chi _{n(\mathscr {T}), \gamma _t(\mathscr {T})}\). Moreover, for \(d>3\), equality occurs if and only if \(\mathscr {T} \in \mathscr {G}_{n,\gamma _t}\).

-

2.

For \(\frac{n}{2} \le \gamma _t\), it holds that \(M_2(\mathscr {T}) \ge \chi '_{n(\mathscr {T}), \gamma _t(\mathscr {T})}\). Additionally, equality occurs if and only if \(\mathscr {T} \in \mathscr {G}_{n,\gamma _t}\).

Proof

When \(n=3\), \(M_1(P_3) = 6 > \chi _{3,2}\) and \(M_2(P_3) = 4 > \chi '_{3,2}\). If \(n=4\), \(M_1(S_4)= 12 > \chi _{4,2}\), \(M_1(P_4)= 10 = \chi _{4,2}\), \(M_2(S_4)= 9 > \chi '_{4,2}\), and \(M_2(P_4)= 8 = \chi '_{4,2}\). While \(n=5\), \(M_2(P_5)= 12 > \chi '_{5,3}\). A tree \(\mathscr {T}\) in \(\mathscr {T}_{n,\gamma _t}\) with \(n \ge 5\) is examined in the case of \(M_1\), and a tree with \(n \ge 6\); \(\frac{n}{2} \le \gamma _t\) is considered for the case of \(M_2\), presuming that all trees of order \(n-1\) meet the inequality. For a diameter \(\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \ldots , \alpha _{d+1}\) of \(\mathscr {T}\), \(\mathscr {T} \cong S_n\) whenever \(d=2\), and \(M_1(S_n) - \chi _{n,2} = (n^2-n)-(6n-14) > 0\) by Lemma 3. Assume \(d \ge 3\). Denote \(d_{\alpha _2}=k,\)\(\ N(\alpha _2) = \{\alpha _1, \alpha _3, \omega _1, \ldots , \omega _{k-2} \},\)\(\ d_{\alpha _3}=q,\)\(\ N(\alpha _3) = \{\alpha _2, \alpha _4, \beta _1, \ldots , \beta _{q-2} \},\)\(\ d_{\alpha _4} = r, \ N(\alpha _4) = \{\alpha _3, \alpha _5, \eta _1, \ldots , \eta _{r-2} \},\)\(\ d_{\alpha _5}=s, \ N(\alpha _5) = \{\alpha _4, \alpha _6, \theta _1, \ldots , \theta _{s-2} \}\), and \(d_{\alpha _6} =p, \ N(\alpha _6) = \{\alpha _5, \alpha _7, z_1, \ldots , z_{p-2} \}\). Subsequently, the following claims are established, forming the basis for a case-wise analysis.

Claim 1

Fix \(d_{\alpha _1}=d_{\omega _1}= \ldots = d_{\omega _{k-2}}=1\) and assume \(d_{\alpha _3} \ge 2\). If \(d_{\alpha _2} \ge 3\), then \(M_1(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) (see Fig. 2).

Proof of Claim 1

Let \(\mathscr {T}_1=\mathscr {T}-\{\alpha _1\}\). Then

Claim 2

Fix \(d_{\alpha _1}=1\), \(d_{\alpha _2}=2\), and assume \(d_{\beta _m} \le 2; \ m \in \{1,2, \ldots , q-2\}\). If there is a minimum TDS \(\mathscr {D}\) satisfying \(|\mathscr {D} \cap N(\alpha _3)| \ge 2\), then \(M_1(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) (see Fig. 2).

Proof of Claim 2

Take \(\mathscr {T}_2 = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1\}\). Then

Claim 3

Fix \(d_{\alpha _1}=1\), \(d_{\alpha _2}=2\), and assume \(d_{\alpha _3} \ge 4\). If \(d_{\beta _m} = 1; \ m \in \{1,2, \ldots , q-2\}\) and \(d_{\alpha _4} \ge 2\), then \(M_1(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) (see Fig. 2).

Proof of Claim 3

Let \(\mathscr {T}_3 = \mathscr {T} - \{\beta _{q-2}\}\). Then

Claim 4

Fix \(d_{\alpha _1}=1, d_{\alpha _2}=2, d_{\alpha _3}=3\), \(d_{\alpha _4} \le 3\) with \(d_{\beta _1}=1\). Then \(M_1(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) (see Fig. 2).

Proof of Claim 4

Consider \(\mathscr {T}_4 = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \beta _1 \}\) and as in Claim 3,

Claim 5

Suppose that \(d_{\alpha _1}=1, d_{\alpha _2}=2, d_{\alpha _3}=3\). Consider \(d_{\alpha _4} \ge 4\) with \(d_{\beta _1}=1\). If \(|N(\alpha _4) \cap \mathscr {D}| \ge 2\), then \(M_1(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) (see Fig. 3).

Proof of Claim 5

Let \(\mathscr {T}_5 = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, \beta _1 \}\). Then

Claim 6

Set \(d_{\alpha _1}=1, d_{\alpha _2}=d_{\alpha _3}=2\), and suppose \(d_{\alpha _4} \ge 3\). If \(|N(\alpha _4) \cap \mathscr {D}| \ge 2\), then \(M_1(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) (see Fig. 3).

Proof of Claim 6

Let \(\mathscr {T}_6 = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3 \}\). Then

Claim 7

Set \(d_{\alpha _1}=1, d_{\alpha _2}=d_{\alpha _3}=d_{\alpha _4}=2\), and assume \(d_{\alpha _5} \ge 4\). Then \(M_1(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) (see Fig. 3).

Proof of Claim 7

Assume \(\alpha _4 \notin \mathscr {D}\). Let \(\mathscr {T}_7 = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, \alpha _4 \}\). Then

Claim 8

Fix \(d_{\alpha _1}=1, d_{\alpha _2}=d_{\alpha _3}=d_{\alpha _4}=2\), and \(d_{\alpha _5}= 3\), where \(\alpha _5 \in \mathscr {D}\). Then \(M_1(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) (see Fig. 4).

Proof of Claim 8

Let \(\mathscr {T}_8 = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3 \}\). Then

Claim 9

Assume that the path \(b_2 b_1 \theta _1 \alpha _5\) is attached to \(\alpha _5\), where \(d_{b_2}=1, d_{b_1}=d_{\theta _1}=2\), and \(d_{\alpha _5}=3\). Fix \(d_{\alpha _1}=1, d_{\alpha _2}=d_{\alpha _3}=d_{\alpha _4}=2\), and \(d_{\alpha _6} \ge 2\). Then \(M_1(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) (see Fig. 4).

Proof

Suppose that \(\alpha _4, \alpha _5 \notin \mathscr {D}\).

Let \(\mathscr {T}_{9} = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, \alpha _4, \alpha _5, \theta _1, b_1, b_2 \}\). Then

Claim 10

Assume that the path \(b_3 b_2 b_1 \theta _1 \alpha _5\) is attached to \(\alpha _5\), where \(d_{b_3}=1, d_{b_2}=d_{b_1}=d_{\theta _1}=2\), and \(d_{\alpha _5}=3\). Set \(d_{\alpha _1}=1, d_{\alpha _2}=d_{\alpha _3}=d_{\alpha _4}=2\). Then \(M_1(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) (see Fig. 4).

Proof of Claim 10

Let \(\alpha _5 \notin \mathscr {D}, \alpha _6 \in \mathscr {D}\). If \(p \ge 2\), take \(\mathscr {T}_{10} = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, \alpha _4, \theta _1, b_1, b_2, b_3 \}\).

Let \(d_{\alpha _7}=i, \ N(\alpha _7) = \{\alpha _6, \alpha _8, y_1, \ldots , y_{i-2} \}\) and \(d_{\alpha _8} =l, \ N(\alpha _8) = \{\alpha _7, \alpha _9, x_1, \ldots , x_{l-2} \}\). It can be seen that \(M_1(P_5) > \chi _{5, 3}\), \(M_1(P_6) > \chi _{6, 4}\), and \(M_1(P_7) > \chi _{7, 4}\). In addition, \(M_2(P_5) > \chi '_{5, 3}\), \(M_2(P_6) > \chi '_{6, 4}\), and \(M_2(P_7) > \chi '_{7, 4}\). Hence it follows from Claims 1-10 that \(d \ge 7, d_{\alpha _2} = d_{\alpha _3} = d_{\alpha _4} = d_{\alpha _5} = 2, \ \alpha _2, \alpha _3, \alpha _6 \in \mathscr {D}\), and \(\alpha _4, \alpha _5 \notin \mathscr {D}\). Furthermore, one can assume that every vertex \(z \in N(\alpha _6) \setminus \{\alpha _5, \alpha _7\}\) satisfies \(d_z \le 2\).

Case A Let \(d_{\alpha _6} = 2\). Take \(\mathscr {T}_{11} = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, \alpha _4 \}\). Then

The equality is observed whenever \(\mathscr {T}_{11} \in \mathscr {T}_{n-4,\gamma _t-2}\) which implies \(\mathscr {T} \in \mathscr {G}_{n,\gamma _t}\).

Case B Suppose that \(d_{\alpha _6} = 3\).

Case B.1 Take \(d_{z_1} = 1\).

Case B.1.a For \(d_{\alpha _7} \le 3\), take \(\mathscr {T}_{12} = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, \alpha _4, \alpha _5, z_1 \}\). Then

Case B.1.b Suppose that \(d_{\alpha _7} \ge 4\).

Case B.1.b.1 While \(|N(\alpha _7) \cap \mathscr {D}| \ge 2\),

take \(\mathscr {T}_{13} = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, \alpha _4, \alpha _5, \alpha _6, z_1 \}\). Then

Case B.1.b.2 Suppose that \(N(\alpha _7) \cap \mathscr {D} = \{\alpha _6\}\).

Case B.1.b.2.a While \(d_{y_1} \ge 2\), by the claims proved above, there is a pendant path \(\alpha _7 y_1 a_1 a_2 a_3 a_4\) attached to \(\alpha _7\) such that \(d_{y_1}=d_{a_1}= d_{a_2}=d_{a_3}=2, d_{a_4}=1\). Since \(d_{\alpha _7} \ge 4\), one can obtain \(M_1(\mathscr {T})> \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T})> \chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) by considering the above cases.

Case B.1.b.2.b Let \(d_{y_m} = 1; \ m \in \{1,2, \ldots , i-2\}\). Take \(\mathscr {T}_{14} = \mathscr {T} - \{y_1\}\). Then

Case B.2 Consider \(d_{z_1} = 2\). From the claims proved above, there is a pendant path \(\alpha _6 z_1 c_1 c_2 c_3 c_4\) attached to \(\alpha _6\) with \(d_{c_1}=d_{c_2}=d_{c_3}=2, d_{c_4}=1\).

Case B.2.a Let \(d_{\alpha _7} = 2\). Take \(\mathscr {T}_{15} = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, \alpha _4, \alpha _5 \}\). Then

Consider \(\mathscr {T}_{16} = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, \alpha _4 \}\). Then

Case B.2.b Let \(d_{\alpha _7} \ge 3\).

Case B.2.b.1 For \(| N(\alpha _7) \cap \mathscr {D}| \ge 2\), by considering the above claims and cases, let \(d_{y_m} \le 3; \ m \in \{1,2, \ldots , i-2\}\). As \(d_{\alpha _8} \ge 1\), take \(\mathscr {T}_{17} = \mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, \alpha _4, \alpha _5, \alpha _6, z_1, c_1,c_2,c_3,c_4\}\). Then

Case B.2.b.2 Consider \(N(\alpha _7) \cap \mathscr {D} =\{\alpha _6\}\). Based on the above claims, suppose that \(d_{y_m} \le 2; \ m \in \{1,2, \ldots , i-2\}\).

Case B.2.b.2.a Let \(d_{y_1}=1\).

Case B.2.b.2.a.1 While \(d_{\alpha _7} \ge 4\), since \(d_{\alpha _8} \ge 1\), take \(\mathscr {T}_{18} = \mathscr {T} - \{y_1\}\). Then

Assume \(d_{y_m} = 1, \ m \in \{1,2, \ldots , i-2 \}\). Then

Case B.2.b.2.a.2 Take \(d_{\alpha _7}=3\).

Case B.2.b.2.a.2.a For \(d_{\alpha _8} \le 3\), take \(\mathscr {T}_{19} = \mathscr {T} - \{y_1, z_1, c_1, c_2, c_3, c_4\}\). Then

Case B.2.b.2.a.2.b Suppose that \(d_{\alpha _8} \ge 4\).

Case B.2.b.2.a.2.b.1 If \(|N(\alpha _8) \cap \mathscr {D}| \ge 2\), take \(\mathscr {T}_{20}\) and \(\mathscr {T}_{21}\) as sub-trees of \(\mathscr {T} - \alpha _7 \alpha _8\) containing \(\alpha _7\) and \(\alpha _8\), respectively, then

Case B.2.b.2.a.2.b.2 Suppose that \(N(\alpha _8) \cap \mathscr {D} =\{\alpha _7\}\). Any path from \(\alpha _8\) to a pendant vertex through \(\alpha _8 x_m; \ m \in \{1,2, \ldots , l-2\}\) has length 4. From the claims, \(M_1(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) can be obtained.

Case B.2.b.2.b Let \(d_{y_m}= 2; \ m \in \{1,2, \ldots , i-2\}\). Any path from \(\alpha _7\) to a pendant vertex through \(\alpha _7 y_m; \ m \in \{1,2, \ldots , i-2\}\) has length 5. Given the above cases, the condition \(d_{\alpha _7} \ge 3\) necessarily implies \(d_{\alpha _7} = 3\). Hence, there is a pendant path \(\alpha _7 y_1 a_1 a_2 a_3 a_4\) attached to \(\alpha _7\) on 6 vertices such that \(d_{y_1}=d_{a_1}=d_{a_2}=d_{a_3}=2\) and \(d_{a_4}=1\).

Case B.2.b.2.b.1 Consider \(d_{\alpha _8}=2\).

Take \(\mathscr {T}_{22} = \mathscr {T} - \{z_1, c_1, c_2, c_3, c_4, y_1, a_1, a_2, a_3, a_4\}\). Then

The equality is intact in when \(\mathscr {T}_{22} \in \mathscr {T}_{n-10,\gamma _t-4}\) implies \(\mathscr {T} \in \mathscr {G}_{n,\gamma _t}\).

Case B.2.b.2.b.2 Let \(d_{\alpha _8} \ge 3\).

Case B.2.b.2.b.2.a While \(|N(\alpha _8) \cap \mathscr {D}| \ge 2\), take \(\mathscr {T}_{23}\) and \(\mathscr {T}_{24}\) as sub-trees of \(\mathscr {T} - \alpha _7 \alpha _8\) containing \(\alpha _7\) and \(\alpha _8\), respectively, then

Case B.2.b.2.b.2.b Suppose that \(N(\alpha _8) \cap \mathscr {D} =\{\alpha _7\}\). Any path from \(\alpha _8\) to a pendant vertex through \(\alpha _8 x_m; \ m \in \{1,2, \ldots , l-2\}\) has length 4. From the claims, \(M_1(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(M_2(\mathscr {T}) > \chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) can be obtained.

Case C Consider \(d_{\alpha _6} \ge 4\). As \(d_{\alpha _7} \ge 1\), take \(\mathscr {T}_{25}=\mathscr {T} - \{\alpha _1, \alpha _2, \alpha _3, \alpha _4, \alpha _5\}\). Then

Consider \(d_{z_m} \le 2, \ m \in \{1,2, \ldots , p-2 \}\).

\(\square\)

Example 1

Figure 5 illustrates an example of a full binary tree, a widely studied data structure in computer science. The vertices colored black represent the minimum TDS of the tree B. Thus, \(B \in \mathscr {T}_{15,6}\). Let \(E_{d_u,d_v}\) denote the number of edges connecting vertices of degrees \(d_u\) and \(d_v\). Then \(E_{1,3}=8, E_{3,3}=4\), and \(E_{2,3}=2\). This yields, \(M_1=66, M_2=72, \chi _{15,6}=60\), and \(\chi '_{15,6}=65.5\). Clearly, Theorem 1 holds for both the cases even also with \(\frac{n}{2} \ge \gamma _t\).

Remark 1

In general, the result for \(M_2\) index in Theorem 1 is not valid for \(\frac{n}{2} \ge \gamma _t\); however, it remains valid for all star graphs \(S_n\); \(n \ne 5\), since

Thus, \(h_2(n) \ge h_2(6) \ge 0\).

Applications and discussion

The structural composition of a molecule profoundly influences its physicochemical and biological properties, which can be systematically analyzed through QSPR modeling. By leveraging mathematical and statistical techniques, this approach establishes correlations between molecular characteristics and their corresponding properties. Graph-theoretic topological indices play a vital role in representing chemical compounds as graphs, enabling the formulation of QSPR models. Regression analysis further strengthens these models by linking molecular descriptors to observed physicochemical and biological behaviors. This section focuses on evaluating the relevance and implications of the obtained results.

Linear regression models for the physicochemical properties of alkanes

As established in Lemma 1, the path graph \(P_n\) attains the minimum values for the first and second Zagreb indices. Since the chemical graphs of unbranched alkanes exhibit isomorphism to path graphs, a correlation analysis has been performed to examine the relevance of the derived lower bounds for these compounds. Statistical analyses and diagram generation were carried out using Python. Table 1 presents the computed values of \(M_1\), \(M_2\), \(\gamma _t\), \(\chi _{n, \gamma _t}\), and \(\chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) for these compounds. Additionally, Table 2 provides experimental data on select physicochemical properties for 15 unbranched alkanes17. This analysis aims to assess whether the derived bounds contribute to predicting key properties such as the logarithm of the partition coefficient (\(\log\) P), molar refraction (MR in \(\text {cm}^3/\text {mol}\)), molar volume (MV in \(\text {cm}^3/\text {mol}\)), parachor (PR in \(\text {cm}^3\)), and polarizability (\(\alpha\) in \(\text {\text{\AA }}^3\)).

The linear correlation between the physicochemical property values and the computed \(\chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(\chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) values for the alkanes is presented in Table 3.

The general form of a linear regression model is expressed as \(y = aX+b\), where y denotes the dependent variable representing the molecular property under investigation, X is the independent variable corresponding to the calculated lower bound value, a is the slope of the regression line, and b is the intercept. To assess the predictive performance and reliability of the regression model, several standard statistical indicators are employed. These include the coefficient of determination (\(R^2\)), root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), standard error (SE), F-statistic, and p value. A detailed summary of these parameters is provided in Tables 4 and 5.

The regression equations arising from the calculated values of \(\chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) and \(\chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\), used to predict the physicochemical characteristics of alkanes, are presented in Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively.

A comparison of the actual and predicted values of the physicochemical properties, based on Eqs. 1 and 2, are presented in Tables 6 and 7, respectively.

The strength of the linear regression analysis can be observed from the residual plots (Figs. 8 and 9) and the corresponding regression fit diagrams (Figs. 6 and 7).

Discussion

-

Although a lower bound was employed as a parameter rather than an exact value in the QSPR analysis, the results reveal a strong agreement with experimental data (see Table 3).

-

The coefficient of determination (\(R^2\)) substantiates the predictive strength of the models with \(R^2 = {\textbf {0.99}}\) for \(\chi _{n, \gamma _t}\) (see Table 4) and \(R^2 = {\textbf {0.97}}\) for \(\chi _{{n,\gamma _{t} }}^{\prime }\) (see Table 5), indicating a high degree of model accuracy across all properties evaluated.

-

As shown in Tables 6 and 7, and illustrated in Figs. 6 and 7, the predicted values for all physicochemical properties are closely aligned with their experimental counterparts.

-

The RMSE and MAE values are notably low across all physicochemical properties, indicating a strong model fit. Furthermore, all predictors are statistically significant (p value \(< 0.01\)) and are associated with high F-statistic values, underscoring the robustness of the regression models (see Tables 4 and 5).

-

The residual plots (see Figs. 8 and 9) show that the residuals are randomly scattered around zero, indicating that the model effectively captures the underlying trend in the data.

Overall, both bounds demonstrate strong predictive capabilities, with only minor deviations observed for select properties. These findings underscore the robustness and reliability of the statistical models, affirming their effectiveness in accurately estimating the physicochemical properties of alkanes and supporting their utility in QSPR studies.

Conclusion, implications and future work

In this study, we established lower bounds for the first and second Zagreb indices of trees under a fixed total domination number, offering a novel domination-theoretic approach to understanding molecular structure through topological descriptors. By integrating these bounds into a QSPR framework, we demonstrated their practical relevance in predicting physicochemical properties of alkanes.

One potential limitation of this study is the use of lower bounds as independent variables rather than the exact topological index values. However, these bounds closely approximate the actual values, and the accompanying statistical analysis reveals strong correlations with experimental measurements, with coefficients of determination reaching up to \(R^2=0.99\). This indicates that the proposed bounds remain highly effective for predicting physicochemical properties such as \(\log\) P, parachor, polarizability, molar refractivity, and molar volume. Additionally, the current formulation of the lower bound for \(M_2\) is applicable specifically to trees satisfying certain total domination number constraints (\(\frac{n}{2} \le \gamma _t\)). This presents an opportunity for future work to explore general bounds that extend to broader classes of trees.

Overall, the findings highlight the potential of combining structural graph theory with QSPR analysis to enhance molecular informatics. The proposed methods not only deepen the theoretical understanding of Zagreb indices in constrained graph classes but also demonstrate their applicability in real-world chemical modeling.

Future work may extend this framework by investigating other graph-theoretic indices and their bounds, exploring their applicability in broader classes of compounds, or integrating these descriptors into more complex structure-property models, as exemplified in recent studies18,19,20.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Trinajstic, N. Chemical Graph Theory (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2018).

Gutman, I. & Trinajstić, N. Graph theory and molecular orbitals. Total \(\varphi\) electron energy of alternant hydrocarbons. Chem. Phys. Lett. 17(4), 535–538 (1972).

Cockayne, E. J., Dawes, R. & Hedetniemi, S. T. Total domination in graphs. Networks 10(3), 211–219 (1980).

Das, K. C., Huh, D.-Y., Bera, J. & Mondal, S. Study on geometric-arithmetic, arithmetic-geometric and Randić indices of graphs. Discrete Appl. Math. 360, 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dam.2024.09.007 (2025).

Mondal, S., Das, K. C. & Huh, D. The minimal chemical tree for the difference between geometric-arithmetic and Randić indices. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 124(1), 27336. https://doi.org/10.1002/qua.27336 (2024).

Mondal, S. & Das, K. C. Complete solution to open problems on exponential augmented Zagreb index of chemical trees. Appl. Math. Comput. 482, 128983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2024.128983 (2024).

Hayat, S., Khan, M. A., Khan, A., Jamil, H. & Malik, M. Y. H. Extremal hyper-Zagreb index of trees of given segments with applications to regression modeling in QSPR studies. Alex. Eng. J. 80, 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2023.08.051 (2023).

Ahmad Jamri, A. A. S., Movahedi, F., Hasni, R., Gobithaasan, R. & Akhbari, M. H. Minimum Randić index of trees with fixed total domination number. Mathematics 10(20), 3729. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10203729 (2022).

Hasni, R., Ahmad Jamri, A.A.S., Arif, N.E., Harun, F.N. (2021) The Randic index of trees with given total domination number. Iranian Journal of Mathematical Chemistry 12(4), 225–237 https://doi.org/10.22052/ijmc.2021.243170.1591

Bermudo, S., Hasni, R., Movahedi, F. & Nápoles, J. E. The geometric-arithmetic index of trees with a given total domination number. Discrete Appl. Math. 345, 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dam.2023.11.024 (2024).

Sun, X., Du, J. & Mei, Y. Lower bound for the Sombor index of trees with a given total domination number. Comput. Appl. Math. 43(6), 356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40314-024-02871-8 (2024).

Mojdeh, D. A., Habibi, M., Badakhshian, L. & Rao, Y. Zagreb indices of trees, unicyclic and bicyclic graphs with given (total) domination. IEEE Access 7, 94143–94149. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2927288 (2019).

West, D. B. Introduction to Graph Theory Vol. 2 (Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 2001).

Haynes, T. W., Hedetniemi, S. T. & Henning, M. A. Topics in Domination in Graphs Vol. 64 (Springer, Berlin, 2020).

Gutman, I. On the origin of two degree–based topological indices. Bulletin (Académie serbe des sciences et des arts. Classe des sciences mathématiques et naturelles. Sciences Mathématiques), 39, 39–52 (2014).

Gutman, I. & Das, K. C. The first Zagreb index 30 years after. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem 50(1), 83–92 (2004).

Mohajeri, A., Manshour, P., Mousaee, M.: A novel topological descriptor based on the expanded Wiener index: applications to QSPR/QSAR studies. Iranian Journal of Mathematical Chemistry 8(2), 107–135 (2017) https://doi.org/10.22052/ijmc.2017.27307.1101

Hayat, S. & Wazzan, S. A computational approach to predictive modeling using connection-based topological descriptors: Applications in coumarin anti-cancer drug properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26(5), 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26051827 (2025).

Hayat, S., Arfan, A., Khan, A., Jamil, H. & Alenazi, M. J. An optimization problem for computing predictive potential of general sum/product-connectivity topological indices of physicochemical properties of benzenoid hydrocarbons. Axioms 13(6), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms13060342 (2024).

Hayat, S., Alanazi, S. J. & Liu, J.-B. Two novel temperature-based topological indices with strong potential to predict physicochemical properties of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with applications to silicon carbide nanotubes. Phys. Scr. 99(5), 055027. https://doi.org/10.1088/1402-4896/ad3ada (2024).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Vellore Institute of Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM contributed to conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and writing the original draft, while PA was responsible for reviewing, editing, and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manuel, M., Parthiban, A. Lower bounds for the Zagreb indices of trees with given total domination number and its applications in QSPR studies of alkanes. Sci Rep 15, 34949 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18870-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18870-6