Abstract

This study explores the impact of online social interaction on college students’ socio-emotional competence in the digital age, as well as its potential mediation mechanisms. Bonding social capital, represented by parent-child and peer relationships, was selected as the mediating variable. Using data from 693 college students in the 2022 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), this paper analyzes the relationship between online social interaction and socio-emotional competence in college students. The findings indicate that online social interaction does not have a significant direct impact on socio-emotional competence, but it indirectly enhances college students’ socio-emotional competence by strengthening bonding social capital. Furthermore, gender and urban-rural differences exhibit some heterogeneity in this relationship, with a more significant mediating effect of bonding social capital among male and rural college student groups. The results provide new insights into how digital technology, through social relationships, affects college students’ socio-emotional competence and offer important implications for educational practices and family education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Socio-emotional competence refers to an individual’s ability to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and express empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions1,2,3,4. In the 21 st century, many international organizations, such as the OECD5,6, and the World Bank7, have emphasized the key role of socio-emotional competence in individual academic development, mental health, and career success. Studies have also confirmed that socio-emotional competence has a significant positive impact on students’ academic performance4,8,9, subjective well-being, and mental health3,6,10. Compared to primary and secondary school students, many college students face a critical stage in their lives when they transition to university11,12,13, which involves adapting to new social and academic environments14and encountering challenges in learning, mental health, interpersonal relationships, and adapting to adult roles15,16,17. Research shows that socio-emotional competence plays a core role during this transition18, significantly correlating with college students’ academic achievement19,20,21, mental health22, and positive emotions23. College students who are skilled in problem-solving and effectively expressing feelings and thoughts in friendships are likely to experience higher levels of intimacy and well-being, with socio-emotional competence significantly correlated with the quality of their friendships and happiness24. Therefore, socio-emotional competence is crucial to the development of college students.

Research indicates that college students’ socio-emotional competence is influenced by many factors, including the school atmosphere25teaching environment26, social-emotional learning project27,28, and teacher support29. In the digital age, the rapid development of the Internet and mobile communication technologies has reshaped human social interaction30,31, with online social interaction becoming one of the major activities on the Internet. College students are highly active users of online social interaction, and there is an urgent need for more empirical research to examine its impact on their socio-emotional competence. Scholars have studied the positive impact of online social interaction on college students’ mental health32,33, and university adaptation34, in Western countries using platforms such as Facebook and Instagram, and have also examined the positive effects of online social interaction on college students’ subjective well-being35, friendship quality36, interpersonal communication, and social support37 in the Chinese context using the WeChat platform. However, research on the impact of online social interaction on college students’ socio-emotional competence in the digital age is still relatively scarce. China, as a typical country with a strong collectivist culture, has deeply influenced individual development through family and peer groups38,39, but few studies have explored the mediating role of bonding social capital, represented by family and peer relationships, in the relationship between online social interaction and socio-emotional competence in Chinese college students.

To fill the gap in existing research, this study examines the impact of online social interaction on college students’ socio-emotional competence based on data from 693 college students in the 2022 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). The study selects bonding social capital, represented by parent-child and peer relationships, as the mediating variable and explores the mediating role of bonding social capital in the relationship between online social interaction and socio-emotional competence in college students. This study aims to address three core questions: (1) Does online social interaction, as a key variable in the digital age, affect college students’ socio-emotional competence? (2) Does bonding social capital mediate the relationship between online social interaction and college students’ socio-emotional competence? (3) Are there heterogeneous effects of online social interaction on college students’ socio-emotional competence and its mechanisms among different gender and urban-rural groups?

Literature review and research hypotheses

Online social interaction and socio-emotional competence

This study focuses on online social interaction, which primarily includes self-disclosure behaviors conducted by individuals on internet platforms (such as sharing on WeChat Moments) and online communication activities with family and friends through text, voice, and video. Although international social platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter are restricted in China, domestic social applications like WeChat and Weibo have continuously attracted hundreds of millions of users, making China one of the largest social media markets in the world. Data shows that, in 2022, the number of social media users in China reached approximately one billion40. College students, as “digital natives,” are among the most active users of social media. For example, a survey of 500 Chinese college students showed that nearly all respondents used WeChat on a daily basis41. The 693 college students in this study are no exception. The widespread penetration of digital media has made online social interaction an influential factor that cannot be ignored when exploring college students’ socio-emotional competence.

According to the widely adopted CASEL five-component framework in the field of socio-emotional competence research, socio-emotional competence typically encompasses five core dimensions: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making42. This framework can be applied and localized across different developmental stages, from early childhood to adulthood, and in cross-cultural educational contexts43. Specifically, self-awareness refers to the ability to understand one’s emotions, thoughts, and values, and how these elements influence behavior in different situations; self-management refers to the ability to effectively manage emotions, thoughts, and behaviors in different situations to achieve goals and aspirations; social awareness refers to the ability to understand others’ perspectives and resonate with individuals from different backgrounds, cultures, and environments; relationship skills refer to the ability to establish and maintain healthy, supportive relationships and to effectively navigate diverse individual and group environments; responsible decision-making refers to the ability to make caring and constructive choices in personal behavior and social interactions42.

The university stage is considered a period of “emerging adulthood”44, which is critical for identity development45, the maturation of interpersonal relationships46, and the development of key socio-emotional competences47. Existing literature indicates that the impact of online social interaction on socio-emotional competence presents a complex dual-edged effect. On one hand, studies suggest that online social interaction can compensate for the emotional support loss caused by a lack of face-to-face social interaction, thereby alleviating depressive symptoms48 and enhancing self-management skills, such as emotional regulation. Online social interaction also helps improve college students’ social skills and university adaptation49, enhancing feelings of social support and self-worth50, which in turn promotes relationship skills, social awareness, and self-awareness. Self-disclosure on social platforms enables college students to receive supportive responses and positive feedback from friends51,52, which helps enhance their empathy, social awareness, and relationship skills. On the other hand, several studies have also identified negative effects of online social interaction. For example, research has shown that excessive online social interaction leads to social media addiction, which in turn contributes to smartphone addiction53, and smartphone addiction is associated with poorer interpersonal communication skills in “phubbing” college students54. A study using a wearable fNIRS system to monitor brain activity found that the use of social media negatively affects cognitive executive function in college students, which further impairs their empathy and emotional regulation abilities55. Therefore, while online social interaction may enhance college students’ socio-emotional competence, its negative impact on socio-emotional competence in certain contexts should also be considered. Based on the mainstream positive impact, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1

Online social interaction has a significant positive predictive effect on college students’ socio-emotional competence.

Mediating role of bonding social capital

This study adopts social capital theory as the core theoretical framework to explore the impact of online social interaction on college students’ acquisition of bonding social capital, as well as the effect of bonding social capital on college students’ socio-emotional competence. According to social capital theory, individual-level social capital is typically divided into bonding social capital and bridging social capital. Bonding social capital originates from emotionally close and highly trusting “strong ties” networks (such as family and close friends), emphasizing emotional support and deep interaction; bridging social capital, on the other hand, comes from “weak ties” networks with high heterogeneity and broad scope, focusing on information exchange and opportunity expansion56,57,58. In contrast to the “Anglo-American style SNS” which primarily promotes weak ties, the WeChat ecosystem in the Chinese context places more emphasis on familiar ties and bonding social capital59. Therefore, this study focuses on bonding social capital in family and peer relationship networks.

College students, in the “emerging adulthood” stage, face the significant challenge of establishing and developing intimate relationships60. They seek to build intimacy by strengthening their connections with family and friends, obtaining emotional support and self-identity. Studies have shown that when weak ties formed by online social interaction replace strong ties with family and friends in offline interactions, frequent internet socializing is associated with increased feelings of loneliness, depression, and stress61. The use of online platforms reduces face-to-face interpersonal communication in real life, thereby increasing loneliness among college students62. Some scholars have pointed out that when internet use contributes to real-life interpersonal communication, increasing the time and frequency of communication with family and friends, it can reduce loneliness63,64. Online social interaction helps increase college students’ connections with family and friends, enabling them to maintain and strengthen existing intimate relationships36,63,64,65,66, thereby consolidating and enhancing bonding social capital33,37,67.

Empirical studies on social capital theory indicate that online social interaction is significantly positively correlated with college students’ social capital68, and social capital is significantly positively correlated with subjective well-being and life satisfaction69. Some scholars have found that bonding social capital provided by family, intimate relationships, and close friends plays a core role in enhancing self-esteem and well-being70. Other studies have shown that the relationship between college students’ WeChat use intensity and life satisfaction and mental health is mediated by bonding social capital59. This is because strong tie networks involve more frequent social interactions, emotional intensity, and intimacy71, as well as more personalized communication72providing individuals with high-quality emotional and continuous support56,57,58. These supports effectively reduce stress52,73,74, thus enhancing self-awareness, self-management, and relationship skills. Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H2

Bonding social capital mediates the relationship between online social interaction and college students’ socio-emotional competence.

H2a

Online social interaction has a significant positive predictive effect on bonding social capital.

H2b

Bonding social capital has a significant positive predictive effect on socio-emotional competence.

Heterogeneity of college students’ socio-emotional competence

Research has shown significant gender differences in emotional expression and regulation. Females are generally better at expressing positive and internalized emotions75, but they may face higher levels of emotional challenges76. In terms of emotion regulation, females are more adept at using positive emotions to reduce negative ones77. However, some studies have indicated that males’ online interpersonal relationship quality is more easily influenced by the amount of time spent on the internet, but as usage time increases, the improvement in males’ online relationships is more pronounced than that in females65. Regarding urban-rural differences, some studies have found that rural household registration is associated with lower levels of anxiety and depression, which has a positive effect on emotional regulation78. However, other research has found that rural groups experience greater emotional and interpersonal relationship pressures79. Based on the above studies, this research proposes the following hypotheses:

H3

There is group heterogeneity in the mediating effect of bonding social capital between online social interaction and college students’ socio-emotional competence.

H3a

There is gender heterogeneity in the mediating effect.

H3b

There is urban-rural heterogeneity in the mediating effect.

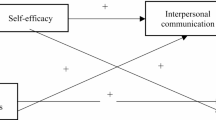

As shown in Fig. 1, this study proposes a conceptual model and the following research hypotheses:

Method

Data source

The data used in this study comes from the 2022 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) database. The sample covers 25 provinces, cities, and autonomous regions, and the survey targets all household members within the sampled households. Different questionnaires were designed for various groups, including community, family, and individual levels, covering areas such as education, economy, family relationships, social interactions, and health. The 2022 individual self-administered questionnaire contains data from 27,001 samples. After screening for the study population, which consists of college students (including both junior college and undergraduate students), the sample was limited to those with valid data for independent variables, dependent variables, mediating variables, and control variables. Samples with missing values (including values of “−1”, “−2”, “−8”, and “−9”) were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 693 valid cases.

Variable definitions

Dependent variable

This study uses the CASEL five-component framework to construct a socio-emotional competence scale for college students based on five dimensions: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. The scale is constructed using 15 items from the 2022 CFPS individual self-administered questionnaire (see Table 1). Prior to data analysis, reverse-coded items were recoded (highest value + 1 minus item score), and the data was standardized using Z-scores to eliminate dimensionality. The Cronbach’s α of the scale is 0.764, indicating good reliability.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to combine the 15 indicators into a comprehensive socio-emotional competence index. The EFA results showed a KMO value of 0.780 (greater than 0.6), and the data passed Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.001), indicating that the data is suitable for factor analysis. The factor analysis extracted five factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. The explained variance of the five factors after rotation was 15.901%, 15.889%, 11.356%, 11.272%, and 8.360%, respectively. The cumulative explained variance after rotation was 62.777%. The factor loading matrix after Promax rotation is shown in Table 2. The communality values for all items are above 0.4 (ranging from 0.438 to 0.831), indicating a strong correlation between the study items and the factors, and the factors can effectively extract information. The calculation formula for the comprehensive socio-emotional competence index is: (15.901 × PC1 + 15.889 × PC2 + 11.356 × PC3 + 11.272 × PC4 + 8.360 × PC5)/62.777.

Independent variable

The independent variable in this study is online social interaction (OSI). This study uses two items from the 2022 CFPS individual self-administered questionnaire to measure online social interaction: “Frequency of sharing on WeChat Moments” (ranging from “almost every day” to “never,” scored 1–7) and “Importance of staying in touch with family and friends online” (ranging from “very unimportant” to “very important,” scored 1–5). First, the item “Frequency of sharing on WeChat Moments” was reverse scored (8 - item score). Then, after performing Z-score standardization to eliminate dimensionality for both items, the mean value was taken as the score for online social interaction.

Mediating variable

The mediating variable in this study is bonding social capital, which includes two dimensions: parent-child relationships and peer relationships. The parent-child relationship is measured using two items from the 2022 CFPS individual self-administered questionnaire: “How is your relationship with your father in the past 6 months?” and “How is your relationship with your mother in the past 6 months?” (scored from 1 to 5, from “very distant” to “very close”). A higher value indicates a closer parent-child relationship. Peer relationships are measured using the item “How good do you think your interpersonal relationships are?” (scored from 0 to 10, from “lowest” to “highest”). A higher value indicates a stronger peer relationship network. Since the original indicators have different scales, this study first conducted Z-score standardization to eliminate dimensionality. Then, non-negative translation was applied to meet the requirements of the entropy method for calculation. Finally, the weights and comprehensive scores were calculated based on these processed data.

Control variables

Previous research has shown that demographic factors such as age, gender, and household registration are important variables affecting socio-emotional competence. Studies indicate that, within college student populations, older students tend to score higher in socio-emotional competencies such as emotional control and expression80. Significant gender differences have been found in emotional challenges, emotional expression, emotional regulation, and the impact of social capital on emotional regulation75,76,77,81. Moreover, household registration (urban vs. rural) affects levels of emotional regulation and the pressure related to emotions and interpersonal relationships78,79. To control for these potential confounding factors, this study includes age (continuous variable), gender (male = 1, female = 0), and household registration (urban = 1, rural = 0) as control variables.

Results

Descriptive statistics

This study conducted descriptive statistical analysis on six core variables in the sample, covering demographic characteristics, online social interaction, bonding social capital, and socio-emotional competence. The descriptive statistics in Table 3 show that, in terms of demographic characteristics, the sample’s age follows an approximately symmetrical distribution (M = 21.330, SD = 3.360), with a balanced gender ratio (Gender = 0.495) and a slightly higher proportion of urban households compared to rural (Urban = 0.551). The mean score for online social interaction is close to zero (M = 0.003, SD = 0.729), indicating an overall moderate level. The bonding social capital score is relatively high (M = 4.259, SD = 0.727), showing that the sample has a strong intimate relationship network. The mean score for socio-emotional competence is close to zero (M = −0.000, SD = 0.348), with a relatively concentrated distribution, but still with some individual variation. It is noteworthy that all variables exhibit varying degrees of variation, suggesting potential group heterogeneity. Subsequent research will further explore the differences in these variables among different gender, household registration.

Correlation analysis

This study analyzed the correlations between the three core variables—online social interaction, bonding social capital, and socio-emotional competence. The Pearson correlation analysis results in Table 4 show that there is a significant moderate positive correlation between bonding social capital and socio-emotional competence (r = 0.394, p < 0.001), indicating that individuals with stronger social relationship networks tend to have higher socio-emotional competence. Online social interaction is also significantly positively correlated with bonding social capital (r = 0.101, p < 0.01), though the correlation is weaker. Notably, the direct correlation between online social interaction and socio-emotional competence is not statistically significant (r = 0.052). This correlation pattern suggests that online social interaction may not directly promote the development of socio-emotional competence, but rather exerts an indirect effect through enhancing bonding social capital as a mediating pathway. Further analysis can test the significance of this indirect path using mediation models.

Baseline regression results

Table 5 presents the baseline regression analysis results of the effect of online social interaction on socio-emotional competence. Model 1, the baseline model, shows that without including any control variables, the positive predictive effect of online social interaction on socio-emotional competence is not statistically significant (β = 0.025, p > 0.05). As control variables such as age (Model 2), gender (Model 3), and household registration (Model 4) are gradually added, the regression coefficients for online social interaction remain stable (β = 0.023–0.027), but they continue to lack statistical significance. The overall model explains a small amount of variance, with R² increasing slightly from 0.003 (Model 1) to 0.032 (Model 4), while the adjusted R² similarly shows limited explanatory power (Adjusted R² ranges from 0.001 to 0.027). In conclusion, after controlling for variables such as age, gender, and household registration, the direct effect of online social interaction on socio-emotional competence remains non-significant, suggesting that further exploration of possible mediating mechanisms is needed. Therefore, hypothesis H1 is not supported.

Mediation mechanism analysis

This study tests the mediation mechanism of online social interaction influencing college students’ socio-emotional competence through bonding social capital, based on the three-step mediation framework proposed by Baron & Kenny (1986)82. The regression analysis results in Table 6 show that, in the total effect model with socio-emotional competence as the dependent variable (Column 1), the direct effect of online social interaction is not significant (β = 0.027, p > 0.05). Next, online social interaction has a significant positive predictive effect on the mediating variable, bonding social capital (β = 0.119, p < 0.01). Furthermore, in the model including both online social interaction and socio-emotional competence (Column 3), bonding social capital shows a significant positive predictive effect on socio-emotional competence (β = 0.186, p < 0.001), while the direct effect of online social interaction remains non-significant (β = 0.005, p > 0.05). With the introduction of the mediating variable, the overall explained variance of the model increases significantly (R² rises from 0.032 to 0.179). These results meet the conditions for a full mediation effect, indicating that bonding social capital fully mediates the relationship between online social interaction and socio-emotional competence. Therefore, hypotheses H2a, H2b, and H2 are supported.

Robustness check

To verify the generalizability and reliability of the research conclusions and avoid biases caused by the choice of dependent variable, measurement methods, or model specification, this study performs robustness checks using three methods: adding control variables, changing the measurement of the dependent variable, and using Bootstrap resampling. The results are shown in Table 7. First, research has indicated that parental education level is an important factor influencing college students’ socio-emotional competence26To verify the generalizability and reliability of the research conclusions and avoid biases caused by the choice of dependent variable, measurement methods, or model specification, this study performs robustness checks using three methods: adding control variables, changing the measurement of the dependent variable, and using Bootstrap resampling. The results are shown in Table 7. First, research has indicated that parental education level is an important factor influencing college students’ socio-emotional competence. Therefore, this study matches data from children and their parents, adding father’s education level (father_edu) and mother’s education level (mother_edu) as control variables (Models 1–3). Models 1–3 show that even after controlling for parental education level, the direct effect of online social interaction remains non-significant (β = 0.039, p > 0.05). Online social interaction still has a significant positive predictive effect on the mediating variable, bonding social capital (β = 0.141 vs. 0.120, p < 0.01). In the model including both online social interaction and socio-emotional competence, bonding social capital continues to show a significant positive predictive effect on socio-emotional competence (β = 0.149 vs. 0.192, p < 0.001).

Next, the method for calculating socio-emotional competence scores was changed from exploratory factor analysis to the entropy method (Models 4–6). Models 4–6 show that the direct effect of online social interaction remains non-significant (β = 0.000, p > 0.05). Online social interaction still has a significant positive predictive effect on the mediating variable, bonding social capital (β = 0.119 vs. 0.120, p < 0.01). In the model including both online social interaction and socio-emotional competence, bonding social capital continues to show a significant positive predictive effect on socio-emotional competence (β = 0.176 vs. 0.192, p < 0.001).

Additionally, this study uses the bias-corrected Bootstrap method recommended by Preacher & Hayes (2008)83and performs 5000 resampling iterations to calculate the bias-corrected confidence intervals to test the statistical significance of the mediation path (as shown in Table 8). First, the confidence interval for the direct effect of online social interaction ([−0.028, 0.038]) contains zero, indicating that the direct effect is not significant. Second, the indirect effect of bonding social capital in the mediation path is 0.022, with a Bootstrap 95% confidence interval of [0.015, 0.078], which does not include zero. This confirms the presence of the mediating effect of bonding social capital and further validates that online social interaction indirectly affects socio-emotional competence entirely through its impact on bonding social capital. In conclusion, a series of robustness checks show that the coefficient estimates of the core variables remain stable, indicating that the research model and conclusions are highly robust.

Heterogeneity analysis

To test potential heterogeneity, we conducted moderated mediation analysis and subgroup mediation analysis with gender and household registration as moderating variables. The moderated mediation model shown in Table 9 indicates that the interaction terms for gender and online social interaction (Gender*OSI), gender and bonding social capital (Gender*BSC), urban-rural household registration and online social interaction (Urban*OSI), and urban-rural household registration and bonding social capital (Urban*BSC) were not statistically significant. These results do not support H3, H3a, and H3b: gender and household registration do not moderate the mediation path between online social interaction and socio-emotional competence.

However, to further explore potential group differences, we conducted subgroup mediation analysis. As shown in Table 10, in the male group, the indirect effect of online social interaction on socio-emotional competence through bonding social capital was significant (effect size = 0.027, 95% CI [0.009, 0.101]); in the female group, the confidence interval for this indirect effect contained zero (effect size = 0.019, 95% CI [−0.000, 0.085]), and it was not significant. Similarly, in the rural sample, the indirect effect was significant (effect size = 0.025, 95% CI [0.015, 0.096]), while in the urban sample, it was not significant (effect size = 0.018, 95% CI [−0.006, 0.084]). Although the interaction terms in the moderated mediation model were not significant, the observed pattern of “significant for males, not significant for females” and “significant for rural, not significant for urban” in the subgroup analysis still suggests a potential trend of heterogeneity. This finding warrants further investigation in future studies with larger sample sizes.

Discussion

Based on the 2022 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) data, this study systematically examines the impact mechanism of online social interaction on college students’ socio-emotional competence and tests the mediating role of bonding social capital, represented by parent-child and peer relationships. The study finds that online social interaction does not have a direct significant effect on socio-emotional competence (β = 0.027, p > 0.05), but it exerts an indirect positive effect through bonding social capital as a mediating variable (β = 0.022, 95% CI [0.015, 0.078]).

First, this study did not find a direct effect of online social interaction on college students’ socio-emotional competence. This finding partially supports the “Internet Paradox” proposed by Kraut et al. (1998), which suggests that internet use may not bring psychosocial benefits61. This result may stem from the counterbalancing of both positive and negative effects brought by online social interaction. For example, excessive online social interaction may lead to social media addiction and a decline in interpersonal communication skills53,54. Moreover, when weak ties formed through online social interaction replace strong ties between family and friends and face-to-face communication in real life, it may result in increased feelings of loneliness61,62. These negative effects may offset some of the positive impacts of online social interaction on socio-emotional competence in college students, such as self-worth perception50self-emotional regulation48, university adaptation49, and interpersonal relationship skills49,52.

However, in contrast to previous studies, this study found that online social interaction is not ineffective in the Chinese context but exerts its influence through bonding social capital. Compared to the overall explained variance in the baseline model (R² = 0.032), the overall explained variance in the mediation model significantly increased (R² = 0.179). Even during robustness checks, when adding control variables for father’s and mother’s education levels, as well as changing the measurement of socio-emotional competence, the overall explained variance in the mediation model still significantly increased (R² = 0.035 vs. 0.153, R² = 0.023 vs. 0.081). These results indicate that bonding social capital plays a key mediating role in the relationship between online social interaction and college students’ socio-emotional competence. This finding aligns with Ellison et al.‘s (2007) research on the use of Facebook social media to enhance mental health through social capital33. This study further refines this mechanism, finding that online social interaction in the Chinese context indirectly promotes college students’ socio-emotional competence by enhancing bonding social capital through familiar ties between family and friends. This finding is consistent with Xia & Liu (2023), who highlighted the emphasis on familiar ties and bonding social capital in China’s WeChat ecosystem59, and it also supports social capital theory, which posits that bonding social capital provides individuals with high-quality emotional and continuous support56,57,58.

Moreover, the heterogeneity analysis shows a trend of gender and urban-rural differences in the impact of online social interaction on college students’ socio-emotional competence. In the male and rural student groups, the indirect effect of online social interaction on socio-emotional competence through bonding social capital was significant (β = 0.027, 95% CI [0.009, 0.101]; β = 0.025, 95% CI [0.015, 0.096]), while in the female and urban student groups, this effect was not significant (β = 0.019, 95% CI [−0.000, 0.085]; β = 0.018, 95% CI [−0.006, 0.084]). These findings enrich our understanding of the “third-level digital divide” (i.e., the differences in the benefits of digital technology use between urban and rural areas)84, and resonate with the research by Lai & Gwung (2013) on males being more likely to enhance relationship quality through internet use65, the study by Yu et al. (2022) on urban-rural differences in individual mental health78, and the research by Cui et al. (2022) on urban-rural differences in emotional and interpersonal relationships79.

Implications and limitations

Theoretical implications

This study makes three main theoretical contributions: First, it applies social capital theory to analyze the relationship between digital social interaction and socio-emotional competence, clarifying the mediating role of bonding social capital, thereby enriching the content and application of social capital theory in the digital age. Second, it validates the core role of family and peer relationships in college students’ development within a collectivist cultural context, showing that even in a highly digitized environment, traditional strong ties remain a significant factor influencing an individual’s socio-emotional competence. Third, by conducting heterogeneity analysis, this study reveals potential differences in the benefits of digital social interaction among different groups, providing a nuanced perspective for future research.

Practical implications

The findings of this study have important implications for educational practices and family communication. First, university mental health education and socio-emotional competence development programs should recognize the potential value of online social interaction and guide students to use social media to maintain high-quality interactions with family and friends. Second, in family education, parents should be aware of the importance of digital communication, actively engage in their children’s online interactions, and provide emotional support and recognition. Finally, policymakers may consider improving students’ online social skills, especially for rural and male students, through digital literacy education, helping them more effectively build and maintain social support networks.

Limitations

This study has several limitations, which also point to important directions for future research. First, this study uses cross-sectional data. Although the stability of the results was validated through robustness checks, reverse causality cannot be ruled out. Future studies could employ multiple longitudinal tracking surveys to analyze the impact of online social interaction at different developmental stages of college students (such as the adaptation period, major selection period, and employment preparation period). Second, bonding social capital in this study is only measured through parent-child and peer relationship networks, which may not fully capture the rich meaning encompassed by bonding social capital. Future research could supplement measurements of the resources embedded in these networks, such as emotional support and instrumental support. Lastly, the quantitative research paradigm used in this study cannot deeply understand the subjective experiences of users. Future research could further explore the process of online social interaction influencing college students’ socio-emotional competence through bonding social capital using netnography or in-depth interviews.

Conclusion

This study systematically examines the impact mechanism of online social interaction on socio-emotional competence in Chinese college students in the digital age, revealing the mediating role of bonding social capital. It provides a new theoretical perspective and practical insights for understanding how digital technology is embedded within social relationship networks in collectivist cultures. The study finds that the direct effect of online social interaction on college students’ socio-emotional competence is not significant and only exerts an impact by promoting bonding social capital to enhance socio-emotional competence. This finding validates the applicability of social capital theory in the digital age and provides empirical evidence for school education, family education, and social policy formulation.

Data availability

This study utilized de-identified, publicly available data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS 2022) database[Https://cfpsdata.pku.edu.cn]. As noted, this is a restricted-access database that requires user registration, login, and approval to obtain the data.

References

Domitrovich, C. E., Durlak, J. A., Staley, K. C. & Weissberg, R. P. Social-Emotional competence: an essential factor for promoting positive adjustment and reducing risk in school children. Child Dev. 88, 408–416 (2017).

Social and emotional learning :Past, present, and future. In Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice (eds Weissberg, R. P. et al.) 3–19 (The Guilford Press, 2015).

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A. & Weissberg, R. P. Promoting positive youth development through School-Based social and emotional learning interventions: A Meta-Analysis of Follow-Up effects. Child Dev. 88, 1156–1171 (2017).

Santos, A. C. et al. Social and emotional competencies as predictors of student engagement in youth: a cross-cultural multilevel study. Stud. High. Educ. 48, 1–19 (2023).

OECD. Skills for Social Progress: The Power of Social and Emotional Skills. (OECD & Publishing, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264226159-en

OECD. Beyond Academic Learning: First Results from the Survey of Social and Emotional Skills (OECD Publishing, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1787/92a11084-en

Sarzosa, M. & Muller, N. Beyond Qualifications: Returns To Cognitive and Socio-Emotional Skills in Colombia (World Bank Group, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-7430

Guo, J. et al. The roles of social-emotional skills in students’ academic and life success: A multi-informant and multicohort perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 124, 1079–1110 (2023).

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D. & Schellinger, K. B. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child. Dev. 82, 405–432 (2011).

Schoeps, K., de la Barrera, U. & Montoya-Castilla, I. Impact of emotional development intervention program on subjective well-being of university students. High. Educ. 79, 711–729 (2020).

Gale, T. & Parker, S. Navigating change: a typology of student transition in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 39, 734–753 (2014).

Hultberg, J., Plos, K., Hendry, G. D. & Kjellgren, K. I. Scaffolding students’ transition to higher education: parallel introductory courses for students and teachers. J. Furth. High. Educ. 32, 47–57 (2008).

Leese, M. Bridging the gap: supporting student transitions into higher education. J. Furth. High. Educ. 34, 239–251 (2010).

Fisher, S. Stress in Academic Life: The Mental Assembly Line. xiii, 106 (Society for Research into Higher Education, Guildford, England, 1994).

Stallman, H. M. Psychological distress in university students: A comparison with general population data. Australian Psychol. 45, 249–257 (2010).

Lipson, S. K. & Eisenberg, D. Mental health and academic attitudes and expectations in university populations: results from the healthy Minds study. J. Ment Health. 27, 205–213 (2018).

Thurber, C. A. & Walton, E. A. Homesickness and adjustment in university students. J. Am. Coll. Health. 60, 415–419 (2012).

Postareff, L., Mattsson, M., Lindblom-Ylänne, S. & Hailikari, T. The complex relationship between emotions, approaches to learning, study success and study progress during the transition to university. High. Educ. 73, 441–457 (2017).

Lanciano, T. & Curci, A. Incremental validity of emotional intelligence ability in predicting academic achievement. Am. J. Psychol. 127, 447–461 (2014).

Iqbal, J. et al. How emotional intelligence influences cognitive outcomes among university students: the mediating role of relational engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 12 (2021).

MacCann, C. et al. Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 146, 150–186 (2020).

Landa, J. M. A., Martos, M. P. & López-Zafra, E. Emotional intelligence and personality traits as predictors of psychological well-being in Spanish undergraduates. Social Behav. Personality: Int. J. 38, 783–794 (2010).

Extremera, N. & Rey, L. Ability emotional intelligence and life satisfaction: positive and negative affect as mediators. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 102, 98–101 (2016).

Demir, M., Jaafar, J., Bilyk, N. & Mohd Ariff, M. R. Social skills, friendship and happiness: A Cross-Cultural investigation. J. Soc. Psychol. 152, 379–385 (2012).

Fang, Z., Fu, Y., Liu, D. & Chen, C. The impact of school climate on college students’ socio-emotional competence: the mediating role of psychological resilience and emotion regulation. BMC Psychol. 13, 1–12 (2025).

Wang, F., Zeng, L. M. & King, R. B. University students’ socio-emotional skills: the role of the teaching and learning environment. Stud. High. Educ. 50, 1670–1687 (2025).

Elmi, C. Integrating social emotional learning strategies in higher education. Eur. J. Invest. Health Psychol. Educ. 10, 848–858 (2020).

Dundas, I., Binder, P. E., Hansen, T. G. B. & Stige, S. H. Does a short self-compassion intervention for students increase healthy self-regulation? A randomized control trial. Scand. J. Psychol. 58, 443–450 (2017).

Wang, F., Zeng, L. M. & King, R. B. Teacher support for basic needs is associated with socio-emotional skills: a self-determination theory perspective. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 28, 76 (2025).

Amichai-Hamburger, Y. Internet and personality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 18, 1–10 (2002).

Steinfield, C., Ellison, N. B., Lampe, C. & Vitak, J. Online Social Network Sites and the Concept of Social Capital. In Frontiers in New Media Research (Routledge, 2013).

Hanna, E. et al. Contributions of social comparison and self-objectification in mediating associations between Facebook use and emergent adults’ psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology Behav. Social Netw. 20, 172–179 (2017).

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C. & Lampe, C. The benefits of Facebook friends: social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Computer-Mediated Communication. 12, 1143–1168 (2007).

Yang, C. & Lee, Y. Interactants and activities on facebook, instagram, and twitter: associations between social media use and social adjustment to college. Appl. Dev. Sci. 24, 62–78 (2020).

Wen, Z., Geng, X. & Ye, Y. Does the use of WeChat lead to subjective Well-Being? The effect of use intensity and motivations. Cyberpsychol Behav. Soc. Netw. 19, 587–592 (2016).

Pang, H. WeChat use is significantly correlated with college students’ quality of friendships but not with perceived well-being. Heliyon 4, e00967 (2018).

Wang, G., Zhang, W. & Zeng, R. WeChat use intensity and social support: the moderating effect of motivators for WeChat use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 91, 244–251 (2019).

Chen, X. & French, D. C. Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 59, 591–616 (2008).

Triandis, H. C. Individualism & Collectivism. xv, 259 (Westview Press, Boulder, CO, US, 1995).

Statista Number of social media users in China 2018–2027. (2025). https://www.statista.com/statistics/277586/number-of-social-network-users-in-china/

Zhou, M. & Zhang, X. Online social networking and subjective well-being: mediating effects of envy and fatigue. Comput. Educ. 140, 103598 (2019).

CASEL CASEL’s SEL Framework. (2020). https://casel.org/casel-sel-framework-11-2020/?view=1

CASEL. What Is the CASEL Framework? (2023). https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-is-the-casel-framework/

Arnett, J. J. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 55, 469–480 (2000).

Chickering, A. W. & Reisser, L. Education and Identity. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series (ERIC, 1993).

Foubert, P. D., Urbanski, L. A. & J. D. & Effects of involvement in clubs and organizations on the psychosocial development of First-Year and senior college students. NASPA J. 43, 166–182 (2006).

Bos, D. J. et al. Distinct and similar patterns of emotional development in adolescents and young adults. Dev. Psychobiol. 62, 591–599 (2020).

Morgan, C. & Cotten, S. R. The relationship between internet activities and depressive symptoms in a sample of college freshmen. CyberPsychology Behav. 6, 133–142 (2003).

Yang, C. & Brown, B. B. Factors involved in associations between Facebook use and college adjustment: social competence, perceived usefulness, and use patterns. Comput. Hum. Behav. 46, 245–253 (2015).

Shaw, L. H. & Gant, L. M. Defense of the internet: the relationship between internet communication and depression, loneliness, self-esteem, and perceived social support. CyberPsychology Behav. 5, 157–171 (2002).

Zhang, R. The stress-buffering effect of self-disclosure on facebook: an examination of stressful life events, social support, and mental health among college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 75, 527–537 (2017).

Kim, J. & Roselyn Lee, J. E. The Facebook paths to happiness: effects of the number of Facebook friends and self-presentation on subjective well-being. Cyberpsychology Behav. Social Netw. 14, 359–364 (2011).

Tanhan, F., Özok, H. İ., Kaya, A. & Yıldırım, M. Mediating and moderating effects of cognitive flexibility in the relationship between social media addiction and phubbing. Curr. Psychol. 43, 192–203 (2024).

Ayar, D. & Gürkan, K. P. The effect of nursing students’ smartphone addiction and phubbing behaviors on communication skill. Comput. Inf. Nurs. 40, 230–235 (2021).

Aitken, A. et al. The effect of social media consumption on emotion and executive functioning in college students: an fNIRS study in natural environment. Res. Sq Rs 3 Rs-5604862. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-5604862/v1 (2024).

Putnam, R. D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community 541 (Touchstone Books/Simon & Schuster, 2000). https://doi.org/10.1145/358916.361990.

Lin, N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action (Cambridge, 2001).

Williams, D. On and off the ’net: scales for social capital in an online era. J. Computer-Mediated Communication. 11, 593–628 (2006).

Xia, M. & Liu, J. Does WeChat use intensity influence Chinese college students’ mental health through social use of wechat, entertainment use of wechat, and bonding social capital? Front. Public. Health. 11, 1167172 (2023).

Subrahmanyam, K., Reich, S. M., Waechter, N. & Espinoza, G. Online and offline social networks: use of social networking sites by emerging adults. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 29, 420–433 (2008).

Kraut, R. et al. Internet paradox. A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am. Psychol. 53, 1017–1031 (1998).

Xie, L., Chen, S., Shang, Y. & Song, D. The effect of internet use behaviors on loneliness: the mediating role of real-life interpersonal communication. Curr. Psychol. 43, 6627–6639 (2024).

Hwang, Y. Antecedents of interpersonal communication motives on twitter: loneliness and life satisfaction. Int. J. Cyber Soc. Educ. 7, 49–70 (2014).

Li, C., Ning, G., Xia, Y., Guo, K. & Liu, Q. Does the internet bring people closer together or further apart?? The impact of internet usage on interpersonal communications. Behav. Sci. 12, 425 (2022).

Lai, C. H. & Gwung, H. L. The effect of gender and internet usage on physical and cyber interpersonal relationships. Comput. Educ. 69, 303–309 (2013).

Cummings, J. N., Lee, J. B. & Kraut, R. Communication technology and friendship during the transition from high school to college. In Computers, Phones, and the Internet: Domesticating Information Technology 265–278 (Oxford University Press, 2006). https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195312805.001.0001.

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C. & Lampe, C. Connection strategies: social capital implications of Facebook-enabled communication practices. New. Media Soc. 13, 873–892 (2011).

Valenzuela, S., Park, N. & Kee, K. F. Is there social capital in a social network site?? Facebook use and college students’ life satisfaction, trust, and participation. J. Computer-Mediated Communication. 14, 875–901 (2009).

Helliwell, J. F. & Putnam, R. D. The social context of well-being. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 359, 1435–1446 (2004).

Bishop, J. A. & Inderbitzen, H. M. Peer acceptance and friendship: an investigation of their relation to self-esteem. J. Early Adolescence. 15, 476–489 (1995).

Han Mo, P. K. et al. Communication in social networking sites on offline and online social support and life satisfaction among university students: tie strength matters. J. Adolesc. Health. 74, 971–979 (2024).

Burke, M. & Kraut, R. E. The relationship between Facebook use and Well-Being depends on communication type and tie strength. J. Computer-Mediated Communication. 21, 265–281 (2016).

Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 38, 300–314 (1976).

Cohen, S. & Wills, T. A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310–357 (1985).

Chaplin, T. M. & Aldao, A. Gender differences in emotion expression in children: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 139, 735–765 (2013).

Graves, B. S., Hall, M. E., Dias-Karch, C., Haischer, M. H. & Apter, C. Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PLOS ONE. 16, e0255634 (2021).

McRae, K., Ochsner, K. N., Mauss, I. B., Gabrieli, J. J. D. & Gross, J. J. Gender differences in emotion regulation: an fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal. Group. Process. Intergroup Relat. 11, 143–162 (2008).

Yu, H. et al. A man-made divide: investigating the effect of urban–rural household registration and subjective social status on mental health mediated by loneliness among a large sample of university students in China. Front. Psychol. 13, 1012393 (2022).

Cui, J. et al. Social media reveals Urban-Rural differences in stress across China. ICWSM 16, 114–124 (2022).

Cerutti, J., Burt, K. B., Moeller, R. W. & Seehuus, M. Declines in social–emotional skills in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 15 (2024).

Kalaitzaki, A., Tsouvelas, G. & Koukouli, S. Social capital, social support and perceived stress in college students: the role of resilience and life satisfaction. Stress Health. 37, 454–465 (2021).

Baron, R. M. & Kenny, D. A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182 (1986).

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods. 40, 879–891 (2008).

Wei, K. K., Teo, H. H., Chan, H. C. & Tan, B. C. Y. Conceptualizing and testing a social cognitive model of the digital divide. Inform. Syst. Res. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1090.0273 (2010).

Funding

No external funding was provided for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing, Ying Xiong; Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Yifei Zhou. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The original survey was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Peking University (Approval No.: IRB00001052-14010).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, Y., Zhou, Y. The impact of online social interaction on college students’ socio-emotional competence mediated by bonding social capital. Sci Rep 15, 33287 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18957-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18957-0