Abstract

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common malignancy in women worldwide and the fourth leading cause of cancer death in women. Although an association between marital status and prognosis has been observed in a variety of malignancies, this link has not been fully elucidated in the field of cervical cancer. A total of 30,853 patients were enrolled in this study, of whom 14,286 (46.3%) were married and 16,567 (53.7%) were unmarried. The median follow-up time was 76 months. Before propensity score matching (PSM), cancer-specific survival (CSS) (HR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.49–1.61, p < 0.001) and overall survival (OS) (HR = 1.66, 95% CI 1.61–1.73, p < 0.001) in unmarried patients were significantly lower than those in married patients. After 1:1 PSM matching, there were 10,771 patients in each of the two groups, and baseline features were balanced (p > 0.05 for all variables). Even after PSM, CSS (HR = 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.13, p = 0.003) and OS (HR = 1.13, 95% CI 1.08–1.18, p < 0.001) of unmarried patients were significantly lower than those of married patients. Multivariate Cox regression analysis confirmed that unmarried status was an independent risk factor for CSS (HR = 1.12, 95% CI 1.07–1.17, p < 0.001) and OS (HR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.14–1.24, p < 0.001). Based on the large sample size analysis, this study revealed the association between unmarried status and poor prognosis of cervical cancer, and confirmed that marital status is an independent factor affecting the prognosis of cervical cancer. Nevertheless, more prospective studies and in-depth mechanistic studies are needed to validate our findings and explore the biological basis behind them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common malignancy among women worldwide and occupies the same position among the causes of cancer death in women1. In 2020, there will be approximately 600,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 340,000 deaths due to cervical cancer worldwide2. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma (AC), and adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) are the three most common histological types of cervical cancer. SCC accounts for about 80% of all cervical cancers. Regardless of the histological type and HPV infection status of patients with cervical cancer, the current mainstream treatment options are surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, or a combination of the above treatments3. Despite the introduction of cervical cancer vaccine and cervical cancer screening for a long time, there are still more new cases of cervical cancer around the world, and even the proportion of young cervical cancer patients in some countries is increasing1, which indicates that cervical cancer is still a serious threat to women’s health worldwide.

Current studies have shown that the prognosis of cervical cancer is related to a variety of factors, mainly the histopathological features of the tumor, such as the size of the primary tumor, lymph node metastasis, lymphatic-vascular space infiltration, staging, and histological grade4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Secondly, some laboratory indicators and their derivatives are also related to the prognosis of cervical cancer13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. With the rise of bio-psychosocial medical models, psychological and social factors have become increasingly important in cancer research23. It is worth noting that marital status has been shown to be associated with the prognosis of various cancers24, such as prostate cancer25,26, early liver cancer27, breast cancer28, pancreatic ductal carcinoma29, glioblastoma30, and non-small cell lung cancer31. Although some previous studies have initially explored the impact of marital status on the prognosis of cervical cancer32,33,34, due to the different control methods of confounding factors, there may be a certain degree of bias. Therefore, there is a lack of a comprehensive study to delve into the link between marital status and cervical cancer prognosis, highlighting the importance of our study. Identifying the link between marital status and cervical cancer prognosis is critical, not only to help clinicians take marital status into account when making treatment plans in order to achieve better treatment outcomes, but also to reveal potential biological mechanisms affecting prognosis and provide directions for exploring new treatment strategies.

In this study, we used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, the largest cancer database in the world, to assess the difference in outcomes between married and unmarried cervical cancer patients. Through this study, we expect to provide new insights into the field of cervical cancer treatment and lay the foundation for future research directions.

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

The patient selection process is shown in Fig. 1. The baseline characteristics of the included patients are shown in Table 1. A total of 30,853 patients were included, with a median follow-up of 76 months. Among them, 16,567 (53.7%) were unmarried and 14,286 (46.3%) were married. A total of 15,154 patients (49.1%) were diagnosed from 2000 to 2008 and 15,699 (50.9%) were diagnosed from 2009 to 2017. There were 13,458 patients (43.6%) aged < 45 years, 10,886 patients (35.3%) aged 45–60 years, and 6,509 patients (21.1%) aged > 60 years. In terms of demographics, most patients were white (76.6%), non-Hispanic (75.8%), had a median household income of less than $75,000 (54.6%), and lived in an urban area (88.2%). In terms of tumor characteristics, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and other histological types accounted for 66.9%, 22.5% and 10.6% of the total population, respectively. There were 4332 (14.0%) well-differentiated patients, 13,055 (42.3%) moderately differentiated patients, and 13,466 (43.7%) poorly differentiated or undifferentiated patients. For cancer stage, 14,347 (46.5%) patients were local, 12,326 (40.0%) patients were regional, and 4180 (13.5%) patients were distant stages. In terms of treatment, 18,700 patients (60.6%) received surgery, 18,443 patients (59.8%) received radiotherapy, and 15,537 patients (50.4%) received chemotherapy.

Before PSM, significant differences were observed between unmarried and married patients in various aspects, including year of diagnosis (p < 0.001), age (p < 0.001), race (p < 0.001), ethnicity (p < 0.001), median household income (p < 0.001), place of residence (p < 0.001), tumor histology (p < 0.001), tumor grade (p < 0.001), cancer stage (p < 0.001), surgery (p < 0.001), radiotherapy (p < 0.001), and chemotherapy (p < 0.001). After 1:1 PSM, 10,771 unmarried patients and 10,771 married patients were included in the analysis, with no significant differences in any of the included variables (all p > 0.05).

Survival outcomes

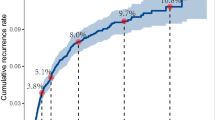

Before PSM, unmarried patients exhibited significantly lower CSS (HR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.49–1.61, p < 0.001, Fig. 2A) and OS (HR = 1.66, 95% CI 1.61–1.73, p < 0.001, Fig. 2B) compared to married patients. After adjustment with 1:1 PSM, although the differences were reduced, unmarried patients still had significantly lower CSS (HR = 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.13, p = 0.003, see Fig. 3A) and OS (HR = 1.13, 95% CI 1.08–1.18, p < 0.001, see Fig. 3B) than married patients. Table 2 details the differences in CSS and OS at key time points of 12 months, 36 months, and 60 months for the two groups before and after PSM. Prior to PSM, unmarried patients had markedly lower CSS at 12 months (84.0% vs. 91.0%), 36 months (69.0% vs. 79.0%), and 60 months (64.0% vs. 75.0%), and similarly lower OS at 12 months (82.0% vs. 91.0%), 36 months (66.0% vs. 78.0%), and 60 months (60.0% vs. 73.0%) compared to married patients. Even after PSM, the CSS at 12 months (88.0% vs. 90.0%), 36 months (74.0% vs. 76.0%), and 60 months (69.0% vs. 71.0%), and the OS at 12 months (87.0% vs. 89.0%), 36 months (71.0% vs. 74.0%), and 60 months (66.0% vs. 69.0%) for unmarried patients remained significantly lower than those for married patients, indicating a less favorable prognosis.

In subgroup analyses, as depicted in Fig. 4, compared to married patients, unmarried patients exhibited lower CSS in the majority of subgroups (HR > 1, p < 0.05). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in CSS among patients in the following subgroups (diagnosed between 2000 and 2008, aged 45–60 years, of other races, Hispanic ethnicity, with a median household income ≥ 75,000 USD, living in rural areas, with adenocarcinoma and other histological types, well-differentiated tumors, localized and distant metastatic stages, who underwent surgery, did not receive radiotherapy, and received chemotherapy) (all p > 0.05). As shown in Fig. 5, except for the subgroups (of other races, living in rural areas, with adenocarcinoma and other histological types, well-differentiated tumors, and not receiving radiotherapy) where no significant impact of marital status on OS was observed (all p > 0.05), in the remaining subgroups, the OS of unmarried patients was significantly lower than that of married patients (HR > 1, p < 0.05).

In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, the year of diagnosis, age, marital status, race, ethnicity, median household income, histological type, tumor grade, stage, surgery, and chemotherapy were identified as independent prognostic factors for both CSS and OS (all with p < 0.05), while radiotherapy was identified as an independent prognostic factor solely for OS (p < 0.001). The results of the Cox regression are presented in Table 3.

Interaction and sensitivity analyses

None of the interactions reached statistical significance (all P > 0.10), and thus the final model was retained without these terms. The detailed results are presented in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Across all sensitivity analyses, unmarried status remained an independent risk factor for both CSS and OS, with hazard-ratio directions consistent with our primary results (Supplementary Table S3).

Discussion

Over the past three decades, marital status has been proven to be associated with the prognosis of various types of cancer24. For instance, María Elena Martínez and her colleagues analyzed data from 145,564 patients with invasive breast cancer from the California Cancer Registry (CCR), finding that in a multivariable-adjusted model, the relative risk of total mortality for unmarried women compared to married women was 1.28 (95% CI 1.24–1.32)28. Similarly, Dechang Zhao and others used data from 58,424 patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the SEER database, discovering that married patients had significantly better OS and CSS compared to unmarried patients, and multivariate COX regression analysis also indicated that being unmarried is an independent risk factor for the prognosis of NSCLC31. The above conclusions have also been confirmed in other types of tumors, including glioblastoma in the nervous system30, prostate cancer in the urinary system25,26, early liver cancer in the digestive system27, and pancreatic ductal carcinoma29. In the field of gynecological malignant tumors, similar findings have been reported. In 2013, a study by Haider Mahdi and others included 49,777 patients with epithelial ovarian cancer, showing that the 5-year overall survival rate for married patients was 45.0%, while for unmarried patients it was 33.1% (p < 0.001). After controlling for confounding factors, married patients had a significantly improved survival rate compared to unmarried patients (HR = 0.8, 95% CI 0.78–0.83, p < 0.001)35. In 2019, a study by Pei Luo and others included 19,276 patients with serous ovarian cancer, finding that the median overall survival for unmarried and married patients was 48 months and 52 months, respectively, and multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated that the risk ratio (HR) for unmarried patients was 1.05 (95% CI 1.00–1.11; P = 0.05)36. In the same year, a study by Jia Dong and others included 39,387 patients with endometrial cancer, identifying marital status as an independent prognostic factor for OS and CSS, with married patients having the lowest risk of death37.

Current research indicates that the impact of marital status on the prognosis of malignant tumors may be related to several factors. In terms of psychosocial factors, cancer patients endure significant psychological stress, and the emotional support provided by a spouse in specific ways can help reduce the negative impact of stress, thereby leading to better therapeutic outcomes28. Studies have also found that individuals who are widowed, divorced, or separated are more likely to suffer from psychological distress during the disease diagnosis and treatment process due to the lack of a partner’s support, increasing the risk of mental health issues38. A healthy marital status not only helps maintain a positive psychological state and reduce negative emotions such as anxiety and depression but also plays a crucial role in improving survival rates39,40. With the emotional support and encouragement of their spouses, married patients are often better able to cope with stress and depression and are more motivated to seek treatment41,42. In addition, the association between optimistic mood and a lower risk of death has been confirmed by prospective studies43. In terms of physiological factors, some studies have suggested that marital status may improve patients’ physiological condition by affecting cardiovascular, endocrine, and immune functions, with the quality of marriage playing a decisive role44,45. A loving and caring partner is associated with an increased release of oxytocin, a hormone that can inhibit the growth of cancer cells through both indirect and direct mechanisms46. In contrast, unmarried patients may be chronically exposed to higher levels of glucocorticoids and catecholamines, which may lead to physiological dysfunction and negatively affect the tumor microenvironment and tumor growth, migration, and angiogenesis, thus impacting prognosis47. At the same time, psychological factors have a strong impact on the tumor immune microenvironment48; depression and stress can reduce the activity of cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells, potentially weakening immune surveillance and promoting tumor growth49. Research has shown that widowed individuals have a poorer peripheral blood lymphocyte response and reduced activity of natural killer cells, which play a key role in identifying and eliminating cancer cells24. HPV infection is a clear cause of cervical cancer, which is a unique aspect of cervical cancer compared to other cancers. Previous studies have indicated that married women have a lower HPV infection rate, especially for high-risk oncogenic HPV types, compared to other unmarried women or women living with partners50. In terms of economic factors, a stable marriage is usually associated with a higher economic status, and family members such as spouses and children may provide financial and emotional support for patients’ long-term treatment51. Married individuals with a better economic foundation are more likely to have health insurance and receive medical assistance at the time of diagnosis52. In terms of compliance, married individuals often adopt healthier lifestyles, including better dietary habits, more exercise, and less drug abuse, which helps improve health outcomes, and a stable marriage can enhance patients’ adherence to treatment regimens53. Marriage and cohabitation with others can moderately improve compliance, and patients from cohesive families show higher compliance than those from conflict-ridden families54, and higher treatment compliance is closely related to better survival outcomes55,56. In addition, married patients are more likely to detect the disease at an early stage and choose active treatment. Compared with unmarried patients, they are more likely to receive chemotherapy and have a higher survival rate, which may be related to the involvement and support of family members in the treatment plan, as well as a higher perceived value of life25.

Some previous studies have preliminarily explored the impact of marital status on the prognosis of cervical cancer32,33,34. In 2010, Mehul K Patel and colleagues analyzed 7997 patients with primary invasive cervical cancer from the SEER database and found that the risk of death for unmarried, separated/divorced, and widowed women was 1.13 (95% CI = 1.03–1.25), 1.41 (95% CI = 1.28–1.57), and 2.51 (95% CI = 2.29–2.76) times higher than that for married women, respectively. However, after adjusting for covariates in the model, no independent association was found between marital status and the risk of death (p = 0.21)32. In 2016, Sanae El Ibrahimi and colleagues studied 31,425 cervical cancer patients from the SEER database, and the results showed that after controlling for relevant confounding factors, the risk of death for unmarried, separated/divorced, and widowed women was significantly increased compared to married women, with hazard ratios of 1.35 (95% CI 1.28–1.43), 1.22 (95% CI 1.15–1.29), and 1.28 (95% CI 1.19–1.36), respectively33. Similarly, Qing Chen and colleagues reported using SEER data that married cervical cancer patients had better OS and CSS than unmarried patients, and marital status was an independent prognostic factor for OS (HR: 0.830, 95% CI 0.798–0.862) and CSS (HR: 0.892, 95% CI 0.850–0.937) in cervical cancer patients34. Although these studies offered valuable preliminary insights and some had sample sizes comparable to ours, their findings have been inconsistent. Therefore, further large-population investigations into the impact of marital status on CSS and OS remain highly valuable. A systematic and comprehensive study of the impact of marital status on the prognosis of cervical cancer can provide key guidance for personalized treatment, reveal potential biological mechanisms, and help formulate targeted public health policies. Our study used patient data from the SEER database to construct a large retrospective cohort and found that unmarried cervical cancer patients had poorer prognosis, and marital status was an independent prognostic factor for cervical cancer. After adjusting for baseline differences with PSM and controlling for covariates with multivariate COX regression analysis, this difference remained significant. It is worth noting that in all subgroup analyses, the prognosis of unmarried cervical cancer patients was not better than that of married patients. In the subgroup analysis based on histological grading, marital status had a significant impact on the CSS and OS of patients with moderately differentiated and poor/undifferentiated cervical cancer, while the impact on well-differentiated cervical cancer patients was not significant for CSS (p = 0.533) and OS (p = 0.125). This phenomenon of non-significance may be due to a small sample size, limiting statistical power, especially when detecting smaller differences, a larger sample size is needed to provide sufficient statistical power, which may also be one of the reasons for the non-significance of the results in several other subgroup analyses.

This study has several notable strengths. First and foremost, by leveraging one of the world’s largest cancer databases—the SEER database—this study was able to utilize its extensive patient data resources. This not only enhanced the statistical power of our analysis but also improved the broad representativeness of the research findings. Second, by employing advanced statistical methods such as PSM and multivariate COX regression, we effectively minimized the potential impact of baseline characteristic differences and covariates on the study results, thereby enhancing the credibility of the conclusions. Third, compared to similar studies, this study controlled for a more comprehensive range of potential confounding factors while including a large sample size, which played a key role in increasing the precision of the research findings. However, this study also faces several limitations. Firstly, as a retrospective study, it may be more susceptible to biases than prospective studies. Secondly, due to data limitations in the SEER database, we were unable to obtain all variables that could potentially affect prognosis, such as smoking history, human papillomavirus infection history, sexual behavior history, reproductive history, chronic disease history, comorbidities, specific chemotherapy regimens and dosages, and special pathological features like lymphovascular space invasion, parametrial invasion, and vaginal margin status, all of which could confound the study results. Thirdly, the SEER database only records the marital status of patients at the time of disease diagnosis and does not update it during the follow-up process, which may introduce certain information biases. Additionally, the SEER database does not record the quality of patients’ marriages, limiting our in-depth exploration of how marital quality affects the prognosis of cervical cancer patients. Existing studies have shown that the closeness of marital relationships has an important impact on the psychological adaptation of cancer patients57. Poor marital relationships may lead to higher levels of dysfunction and worse health behaviors, thereby affecting the prognosis of cancer58. Fourthly, the SEER database only records legally recognized marriages and does not document de facto cohabiting partner relationships; our study classified cohabiting partners as unmarried, yet patients with cohabiting partners may receive equal emotional and socioeconomic support. Although the proportion of such patients is small, it may still affect the study results. Fifthly, the absence of recurrence and quality-of-life (QoL) information in SEER prevented us from assessing disease-free survival (DFS) and QoL, key indicators of long-term prognosis. Future prospective studies should incorporate these endpoints to provide a more comprehensive assessment. Lastly, since the SEER database mainly covers white and black populations, this may limit the applicability of our research findings to other racial groups, such as individuals of Asian descent. Therefore, well-designed, large-scale prospective studies that include a more diverse range of racial groups are needed in the future to further verify the impact of marital status on the prognosis of cervical cancer.

Conclusion

In summary, our study, based on an in-depth analysis of a large sample of data, has revealed a significant association between unmarried status and poor prognosis in cervical cancer, confirming marital status as an independent prognostic indicator. However, to further validate these findings and gain a deeper understanding of the underlying biological mechanisms, we urgently need to conduct more prospective studies and mechanistic investigations. At the same time, it is necessary to carry out further research to explore the impact of marital satisfaction and quality on the prognosis of cervical cancer patients, with the aim of improving their outcomes.

Methods

Data source

The SEER database is a comprehensive cancer statistics database managed by the National Cancer Institute. It collects data on the incidence, prevalence, survival, and mortality rates of cancer in each region of the United States. This study used the SEER-17 dataset from 2000 to 2021, covering approximately 26.5% of the total U.S. population.

Patient selection

In this study, we identified primary cervical cancer cases from 2000 to 2021 in the SEER-17 data set using the codes C53.0, C53.1, C53.8, and C53.9, based on the International Classification of Diseases in Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3) coding system. The study was limited to adults aged 18 years and older, all of whom were histologically confirmed and each patient was assured of having only one primary malignant tumor, cervical cancer. During the screening process, we excluded cases with zero or unknown follow-up time and those with unclear information on oncology outcomes, including cancer-specific survival and overall survival. In addition, patients whose marital status was unknown at diagnosis, as well as cases with missing information in other subgroups (race, ethnicity, median household income, place of residence, histological type, grade, stage, surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy), were not included in the final analysis. In the end, 30,853 patients were enrolled in the study.

Variable processing

Based on the coding system of the SEER database, we obtained patients’ demographic characteristics (including age, year of diagnosis, marital status, race, ethnicity, median household income, and place of residence), oncology characteristics (including histological type, grade, stage, and regional lymph nodes), and treatment measures (surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy). In addition, we determined tumor prognosis, including cancer-specific survival (CSS) and overall survival (OS), based on the patient’s final state and duration of follow-up. In the SEER-17 dataset from 2000 to 2021, cancer staging is classified into three categories: “Localized” who is limited to the primary organ, “Regional” who has spread to nearby tissues, and “Distant” who has metastasized far away. Median household income (adjusted to 2022) was categorized as follows: < 40,000 United States Dollar (USD), 40,000–44,999 USD, 45,000–49,999 USD, 50,000–54,999 USD, 55,000–59,999 USD, 60,000–64,999 USD, 65,000–69,999 USD, 70,000–74,999 USD, 75,000–79,999 USD, 80,000–84,999 USD, 85,000–89,999 USD, 90,000–94,999 USD, 95,000–99,999 USD, 100,000–109,999 USD, 110,000–119,999 USD, and 120,000 + USD. Marital status was classified as Married, Single (never married), Separated, Divorced, Widowed, and Unmarried or Domestic Partner.

In the subsequent statistical analysis, we divided the years of diagnosis into 2000–2008 and 2009–2017, the age of patients at diagnosis into < 45 years, 40–60 years, > 60 years, and the marital status at diagnosis into married and unmarried (including single, separated, divorced, widowed, and unmarried or domestic partner). Racial groups were classified as white, black, and other (Asian or Pacific Islander and American Indian/Native Alaska), ethnic groups as Hispanic and non-Hispanic, median household income as < 75,000 USD and ≥ 75,000 USD, and residence as urban and rural. These cases were classified into squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and other types based on histological coding. Histological grades were Well, Moderately and Poorly/Undifferentiated.

Statistical analysis

The patients were divided into married and unmarried groups according to their marital status. Differences in baseline features between the two groups were determined by Wilcoxon rank sum test and Pearson Chi-square test, as appropriate. The tumor outcome measures we were interested in were OS and CSS. Kaplan–Meier curves and Log-rank tests were used to assess differences in CSS and OS between the two groups. Subsequently, to reduce the impact of baseline differences on survival, we performed 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM). After PSM, Kaplan–Meier curves and Log-rank tests were used again to assess the effects of marital status on CSS and OS. In addition, subgroup analyses were performed based on predetermined variables. Finally, multivariate COX regression analysis was used to verify the independent effects of marital status on CSS and OS. In univariate COX regression, variables with a p value less than 0.05 were included in multivariate COX regression. To assess whether marital status interacts with socioeconomic characteristics (race, ethnicity, median household income, and residence), we included interaction terms in the multivariable Cox models and evaluated their significance using likelihood-ratio tests (LRTs). To assess the robustness of our findings across different matching methods and model assumptions, we conducted three sensitivity analyses (stabilized inverse-probability-of-treatment weighting as an alternative to PSM; full-cohort multivariable regression to adjust for confounding; re-classifying cohabiting but unmarried partners as “married” to evaluate the impact of cohabitation). All statistical analyses in this study were performed using R software (version 4.3.0). All P-values were bilateral, and the threshold of significance was set at 0.05.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in software package SEER*Stat 8.4.3 (https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/).

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Singh, D. et al. Global estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2020: A baseline analysis of the WHO global cervical cancer elimination initiative. Lancet Glob. Health 11, e197–e206 (2023).

Abu-Rustum, N. R. et al. NCCN Guidelines® insights: cervical cancer, Version 1.2024. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 21, 1224–1233 (2023).

Brambs, C. E. et al. The prognostic impact of grading in FIGO IB and IIB squamous cell cervical carcinomas. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 79, 198–204 (2019).

Bhatla, N. et al. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 145, 129–135 (2019).

Matsuo, K., Machida, H., Mandelbaum, R. S., Konishi, I. & Mikami, M. Validation of the 2018 FIGO cervical cancer staging system. Gynecol. Oncol. 152, 87–93 (2019).

Wright, J. D. et al. Prognostic performance of the 2018 international federation of gynecology and obstetrics cervical cancer staging guidelines. Obstet. Gynecol. 134, 49–57 (2019).

McComas, K. N. et al. The variable impact of positive lymph nodes in cervical cancer: Implications of the new FIGO staging system. Gynecol. Oncol. 156, 85–92 (2020).

Gien, L. T. & Covens, A. Lymph node assessment in cervical cancer: prognostic and therapeutic implications. J. Surg. Oncol. 99, 242–247 (2009).

Balaya, V. et al. Validation of the 2018 FIGO classification for cervical cancer: lymphovascular space invasion should be considered in IB1 stage. Cancers (Basel) 12, 3554 (2020).

Margolis, B. et al. Prognostic significance of lymphovascular space invasion for stage IA1 and IA2 cervical cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 30, 735–743 (2020).

Ten Eikelder, M. et al. Does the new FIGO 2018 staging system allow better prognostic differentiation in early stage cervical cancer? A dutch nationwide cohort study. Cancers (Basel) 14, 3140 (2022).

Zhao, M. et al. Predictive significance of lymphocyte level and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio values during radiotherapy in cervical cancer treatment. Cancer Med. 12, 15820–15830 (2023).

Nomelini, R. S., Mota, S. & Murta, E. Absolute band neutrophils count is a predictor of overall survival in advanced uterine cervical cancer. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 306, 1697–1701 (2022).

Menczer, J. Preoperative elevated platelet count and thrombocytosis in gynecologic malignancies. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet 295, 9–15 (2017).

Wang, X., Xu, J., Zhang, H. & Qu, P. The effect of albumin and hemoglobin levels on the prognosis of early-stage cervical cancer: A prospective, single-center-based cohort study. BMC Womens Health 23, 553 (2023).

Lin, F. et al. Predictive role of serum cholesterol and triglycerides in cervical cancer survival. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 31, 171–176 (2021).

Wang, H., Wang, M. S., Zhou, Y. H., Shi, J. P. & Wang, W. J. Prognostic values of LDH and CRP in cervical cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 13, 1255–1263 (2020).

Yu, J. et al. Systematic re-analysis strategy of serum indices identifies alkaline phosphatase as a potential predictive factor for cervical cancer. Oncol. Lett. 18, 2356–2365 (2019).

Niu, Z. & Yan, B. Prognostic and clinicopathological effect of the prognostic nutritional index (PNI) in patients with cervical cancer: A meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 55, 2288705 (2023).

Guo, J. et al. Prognostic value of inflammatory and nutritional markers for patients with early-stage poorly-to moderately-differentiated cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Control 30, 10732748221148912 (2023).

Jiang, P. et al. Predicting the recurrence of operable cervical cancer patients based on hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet (HALP) score and classical clinicopathological parameters. J. Inflamm. Res. 15, 5265–5281 (2022).

Blay, J. Y. Evolution in soft tissue sarcoma. Future Oncol. 13, 1–2 (2017).

Krajc, K. et al. Marital status and survival in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 12, 1685–1708 (2023).

Chen, Q. et al. A study on the impact of marital status on the survival status of prostate cancer patients based on propensity score matching. Sci. Rep. 14, 6162 (2024).

Li, Y., Ma, X., Guan, C. & Yang, X. Analysis of the influence of marital status on prognosis of prostate cancer patients based on big data. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 10, 320–326 (2022).

Chen, F., Wu, Y., Xu, H., Song, T. & Yan, S. Impact of marital status on overall survival in patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 12, 19923 (2022).

Martínez, M. E. et al. Prognostic significance of marital status in breast cancer survival: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 12, e0175515 (2017).

Chen, Q. et al. Studying the impact of marital status on diagnosis and survival prediction in pancreatic ductal carcinoma using machine learning methods. Sci. Rep. 14, 5273 (2024).

Hu, S., Sun, C., Chen, M. & Zhou, J. Marital status as an independent prognostic factor in patients with glioblastoma: A population-based study. World Neurosurg. 182, e559–e569 (2024).

Zhao, D. et al. The independent prognostic effect of marital status on non-small cell lung cancer patients: A population-based study. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 10, 1136877 (2023).

Patel, M. K. et al. Impact of marital status on survival among women with invasive cervical cancer: Analysis of population-based surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data. J. Low Genit. Tract. Dis. 14, 329–338 (2010).

El Ibrahimi, S. & Pinheiro, P. S. The effect of marriage on stage at diagnosis and survival in women with cervical cancer. Psychooncology 26, 704–710 (2017).

Chen, Q., Zhao, J., Xue, X. & Xie, X. Effect of marital status on the survival outcomes of cervical cancer: A retrospective cohort study based on SEER database. BMC Womens Health 24, 75 (2024).

Mahdi, H. et al. Prognostic impact of marital status on survival of women with epithelial ovarian cancer. Psychooncology 22, 83–88 (2013).

Luo, P., Zhou, J. G., Jin, S. H., Qing, M. S. & Ma, H. Influence of marital status on overall survival in patients with ovarian serous carcinoma: Finding from the surveillance epidemiology and end results (SEER) database. J. Ovarian Res. 12, 126 (2019).

Dong, J., Dai, Q. & Zhang, F. The effect of marital status on endometrial cancer-related diagnosis and prognosis: A surveillance epidemiology and end results database analysis. Future Oncol. 15, 3963–3976 (2019).

Holmes, T. H. & Rahe, R. H. The social readjustment rating scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 11, 213–218 (1967).

Irani, E., Park, S. & Hickman, R. L. Negative marital interaction, purpose in life, and depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older couples: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. Aging Ment. Health 26, 860–869 (2022).

Zhu, P., Chen, C., Liu, X., Gu, W. & Shang, X. Factors associated with benefit finding and mental health of patients with cancer: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer 30, 6483–6496 (2022).

Aizer, A. A. et al. Multidisciplinary care and pursuit of active surveillance in low-risk prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 3071–3076 (2012).

DiMatteo, M. R., Lepper, H. S. & Croghan, T. W. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 2101–2107 (2000).

Kim, E. S. et al. Optimism and cause-specific mortality: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 185, 21–29 (2017).

Gallo, L. C., Troxel, W. M., Matthews, K. A. & Kuller, L. H. Marital status and quality in middle-aged women: Associations with levels and trajectories of cardiovascular risk factors. Health Psychol. 22, 453–463 (2003).

Herberman, R. B. & Ortaldo, J. R. Natural killer cells: their roles in defenses against disease. Science 214, 24–30 (1981).

Ai, L. et al. Effects of marital status on survival of medullary thyroid cancer stratified by age. Cancer Med. 10, 8829–8837 (2021).

Antoni, M. H. et al. The influence of bio-behavioural factors on tumour biology: Pathways and mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 6, 240–248 (2006).

Furman, D. et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med. 25, 1822–1832 (2019).

Reiche, E. M., Nunes, S. O. & Morimoto, H. K. Stress, depression, the immune system, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 5, 617–625 (2004).

Hariri, S. et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus among females in the United States, the national health and nutrition examination survey, 2003–2006. J. Infect. Dis. 204, 566–573 (2011).

Xu, C. et al. Socioeconomic factors and survival in patients with non-metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 108, 1253–1262 (2017).

Yang, K. B. et al. Contribution of insurance status to the association between marital status and cancer-specific survival: A mediation analysis. BMJ Open 12, e060149 (2022).

Ding, Z., Yu, D., Li, H. & Ding, Y. Effects of marital status on overall and cancer-specific survival in laryngeal cancer patients: A population-based study. Sci. Rep. 11, 723 (2021).

DiMatteo, M. R. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 23, 207–218 (2004).

Chirgwin, J. H. et al. Treatment adherence and its impact on disease-free survival in the breast international Group 1–98 trial of tamoxifen and Letrozole, alone and in sequence. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 2452–2459 (2016).

Gustafsson, U. O., Oppelstrup, H., Thorell, A., Nygren, J. & Ljungqvist, O. Adherence to the ERAS protocol is associated with 5-year survival after colorectal cancer surgery: a retrospective cohort study. World J. Surg. 40, 1741–1747 (2016).

Manne, S. & Badr, H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer 112, 2541–2555 (2008).

Yang, H. C. & Schuler, T. A. Marital quality and survivorship: Slowed recovery for breast cancer patients in distressed relationships. Cancer 115, 217–228 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 82272710) and the Health Care Scientific and Technology Project of Sichuan Province (2022-1701). We acknowledged the contributions of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program registries for creating and updating the SEER database.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 82272710) and the 2024NSFC1875, Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Department.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was designed by Kaige Pei and Mingrong Xi. Data extraction, statistical analysis, interpretation of data and manuscript drafting were performed by Kaige Pei. All authors were involved in revision of the manuscript and approved the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval was waived by the local ethics committee, as SEER data is publicly available and de-identified.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pei, K., Xi, M. The effect of marital status on cervical cancer related prognosis: a propensity score matching study. Sci Rep 15, 35166 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19122-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19122-3