Abstract

Water scarcity and declining water quality, fueled by uncontrolled industrialization and population growth, have rendered water security a critical global challenge. A principal contributor to this ecological threat is the indiscriminate discharge of industrial effluents, especially dyes, into aquatic systems. As a remedial strategy, electrospun polyacrylonitrile nanofibers integrated with MIL-101(Fe) and graphene oxide (E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO NFs) were engineered as a high-performance and cost-effective adsorbent. Its analytical applicability was demonstrated using a thin-film solid-phase microextraction (TF-SPME) platform, followed by UV-Vis detection, for the sequestration of methyl orange (MO) and congo red (CR), two anionic azo dyes, from textile industry wastewaters (TIWWs). The integration of these materials into the polymeric network imparted exceptional attributes, including a satisfactory specific surface area (SSA, 21.48 m2 g-1), augmented functionalities, enhanced extractability (2.27-fold for MO and 2.54-fold for CR), desirable adsorption capacities (108.015 mg g-1 for MO and 102.704 mg g-1 for CR), and exemplary reusability (< 5% loss after 15 cycles). Electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and π-π stacking were identified as the predominant driving forces governing this mechanism. The proposed methodology offered satisfactory analytical merits, including an expansive linear dynamic range (LDR: 0.05–3.0 mg L-1), low limits of detection (LODs: 0.017 mg L-1 for MO and 0.026 mg L-1 for CR), a low limit of quantification (LOQ: 0.05 mg L-1), and adequate precision (RSD%: 2.52–4.60%). The experimental outcomes validated that the proposed TF-SPME/UV-Vis technique, employing E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO NFs, offers a promising approach for the sequestration of pollutant dyes and the remediation of contaminated waters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water is one of the most important natural resources in the world and its quality directly affects the lives of various creatures1,2. Fast population growth and uncontrolled industrialization have led to water contamination by harmful substances and chemical agents at an alarming rate3. The discharge of pollutants, including organic compounds, synthetic dyes, heavy metals, and pesticides from diverse laboratories and industries not only leads to water contamination but also causes numerous health and environmental issues, such as liver and kidney damage, decreased soil fertility, and diminished photosynthetic activity of aquatic plants, creating anoxic conditions for aquatic flora and fauna4,5,6. Among these pollutants, dye-laden wastewater constitutes a major ecological concern7. According to World Health Organization (WHO) reports, nearly 700,000 tons of synthetic dyes contaminate aquatic systems at levels exceeding safe limits, with approximately 80% originating from untreated discharges8,9.

Within the diverse spectrum of synthetic organic dyes, azo compounds—which contain aromatic and azo (-N = N-) groups—have garnered remarkable attention due to their high chemical stability and xenobiotic nature, rendering them resistant to degradation by conventional wastewater treatment methods, including exposure to light, activated sludge, and chemical agents10,11. Methyl orange (MO) and Congo red (CR) are two anionic azo dyes predominantly used in textile fiber production, yet they are highly stable and scarcely biodegradable12. Even at trace concentrations, MO and CR can exert deleterious effects13,14. Therefore, monitoring these dyes in industrial effluents is essential for environmental protection and pollution control15. Various analytical techniques have been applied for this purpose, comprising high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)16,17gas chromatography (GC)18,19, and ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometry20,21. Of these methods, UV-Vis offers several advantages, such as simplicity, rapid response, low cost, nondestructive sampling, portability, and minimal environmental impact22,23.

Several methodologies have been implemented for dye treatment, namely adsorption, photocatalytic degradation, and membrane processes, with adsorption being favored owing to its simplicity, high efficiency, and cost-effectiveness. The main hindrances of the other two techniques are the generation of toxic by-products and the time-consuming and costly nature of the procedures24,25. Recently, sustainable approaches have been widely adopted to synthesize adsorbents, facilitating efficient and ecologically responsible dye adsorption from wastewaters.

The complexity of industrial wastewater matrices necessitates effective sample preparation approach. Solid-phase extraction (SPE), known for its reduced consumption of time and organic solvents, is extensively applied. Solid-phase microextraction (SPME) was developed as a miniaturized form of SPE, offering minimal solvent usage, high extraction recovery, and satisfactory pre-concentration factors26. Owing to the small quantities of adsorbent employed, the physicochemical and structural traits of the sorbent underpin the extraction performance. To this end, a wide range of inorganic and organic materials have been investigated as SPME sorbents, including clay27, zeolites28, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)29, polymeric compositions30,31, and biochar/hydrochar32,33. The challenges of thoroughly recollecting powdered adsorbents, multi-step synthesis processes demanding sophisticated equipment, and limited reusability are considered major weaknesses of such materials34,35. In this context, the development of promising adsorbents to prevail the above-mentioned deficiencies for detecting and quantifying dyes in aquatic environments is crucial36,37. Nanofiber-based adsorbents, owing to their porous network and high surface area, not only overcome the aforesaid impediments but also possess the flexibility to be tailored for specific applications through the incorporation of various advanced additives into the polymer matrix38.

Among various SPME formats, thin-film SPME (TF-SPME) has been highlighted for its swift extraction, high sensitivity, and large surface-to-volume ratio. In TF-SPME, small segments of the adsorbent mat are either directly immersed in the sample solution or placed in the headspace above it7,39. To realize the benefits of nanofiber-based adsorbents, several fabrication approaches have been developed. Template synthesis40, self-assembly41, phase separation42, drawing43, and electrospinning44 are among the various methods for nanofiber (NF) fabrication. Among these techniques, electrospinning is commonly used to synthesize adsorbents at the nanoscale with well-defined morphology and controllable structure, providing excellent mechanical performance, high surface area, and desirable porosity with fine pores45. In recent years, electrospun (E-spun) NFs have attracted substantial attention in water treatment, particularly for the extraction of organic dyes, heavy metals, toxins, and pathogens46.

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) is among the most widely utilized polymers for electrospinning, stemming from excellent mechanical, thermal, and hydrophobic attributes. The presence of nitrile moieties (C ≡ N) along its backbone further facilitates the adsorption of organic pollutants47,48. To enhance functionality and, consequently, elevate adsorption capacity, pristine PAN NFs are often modified. Accordingly, incorporation of PAN with MIL-101(Fe), an iron-based MOF possessing a multistage pore structure, enables efficient capture of active species within its pores49. Graphene oxide (GO) was incorporated into the PAN/MIL-101(Fe) matrix to reinforce the skeletal structure, increase the abundance of oxygen-containing functionalities, and intensify π-π stacking interactions, without significantly disrupting the NF network. This, in turn, improved the hydrophilicity of NFs and facilitated the diffusion of targeted molecules50,51,52. Up to now, several studies have reported on PAN-based adsorbents incorporated with MIL-101(Fe) and GO. Xu et al.53 fabricated porous PAN/PVP-MIL-101(Fe) NFs, which manifested good structural stability and selective phosphate removal from water (92.3% after seven cycles). However, the fabricated NFs showed moderate adsorption capacity (84.69 mg g-1), limited reusability (only eight cycles), and required a multi-stage synthesis procedure, including an additional step for pore formation via PVP removal. Karimiyan et al.54 synthesized PAN/GO NFs for microextraction by packed sorbent (MEPS) of anesthetic drugs and their metabolites from human plasma at low concentration levels, achieving good selectivity and acceptable recoveries (91–111%). Nonetheless, the use of graphene-based materials in MEPS can cause overpressure in the syringe due to material obstruction55. Moreover, the proposed adsorbent exhibited relatively high matrix effects (−2.3% to −10.2%), which may restrict its practical applicability. Huang et al.56 reported E-spun GO/MIL-101(Fe)/poly(acrylonitrile-co-maleic acid) NFs for the determination of rhodamine B from water samples. Although the adsorbent was reusable for up to 20 cycles, it revealed a very low adsorption capacity (10.46 mg g⁻¹) and required an extended contact time (~ 60 min).

The shortcomings of previous adsorbents—such as moderate capacity, high chemical consumption, slow kinetics, and limited reusability—have here been individually rectified. Accordingly, a streamlined route was implemented in this research to design a reusable, cost-effective, and high-performance E-spun NF adsorbent, composed of PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO, for the adsorption of MO and CR from textile industry wastewaters (TIWWs) utilizing the TF-SPME/UV-Vis approach. Beyond testing in simple laboratory matrix solutions, the adsorbent demonstrated high accuracy (RR%, 89.00–102.50%) and negligible matrix effects (ME%, 84.30–95.38%) in TIWWs, even at short adsorption-desorption cycle times, while reducing solvent consumption in comparison to conventional removal methods, thereby enhancing economic feasibility. From a quantitative viewpoint, the adsorbent displayed the desired adsorption capacity (102.704–108.015 mg g−1) at elevated concentration levels with reasonably fast kinetics. Moreover, the analytical performance of the proposed extraction methodology was rigorously appraised in terms of limit of detection (LOD, 0.017–0.026 mg L−1), precision (RSD%, 2.51–4.75%), and extraction recovery (ER%, 80.63–81.06%).

Experimental section

Reagent and materials

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN, (C3H3N)n, Mw = 230,000), iron (III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3.6H2O), 1,4-benzenedicarboxylicacid (Terephthalic acid, C6H4−1,4-(CO2H)2, H2BDC, 98%), methyl orange (MO, C14H14N3NaO3S, ACS reagent, dye content 85%), and congo red (CR, C32H22N6Na2O6S2, dye content ≥ 35%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. N, N-dimethyl formamide (DMF, C3H7NO), acetonitrile (ACN, CH3CN, LiChrosolve), ethanol (EtOH, C2H6O, 99.8% ACS), methanol (MeOH, CH3OH, ACS), acetic acid (HOAc, CH3COOH, glacial 100%), and hydrochloric acid (HCl, 36%) were bought from Merck Millipore.

Apparatus

UV–Vis spectroscopy was conducted employing a UV-S600 spectrophotometer (Analytik Jena, Germany) for qualitative and quantitative analyses. An FTIR-ATR spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet Nexus 470, Massachusetts, USA) was implemented to investigate the functionality of adsorbent’s components within the mid-IR range of 600 to 4000 cm−1. Morphological and surface structural insights were examined via field emission-scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, FEI ESEM QUANTA 200, USA). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX, EDAX Silicon Drift 2017, USA) and mapping were conducted to analyze the elemental composition and their distribution on the adsorbent. The crystalline nature of the adsorbent was characterized by a powder X-ray diffractometer (PXRD, X’Pert MPD model of Philips, Holland company) over a 2θ range of 1⁰- 80⁰, applying Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54060 Å) under operating conditions of 40 kV and 40 mA. Solution stirring and agitation were carried out using a Heidolph MR Hei Standard Stirrer (Schwabach, Germany) and an IKA vortex (USA), respectively.

Synthesis of components and adsorbent

Synthesis of MIL-101(Fe)

Following Skobelev’s methodology57, approximately 2.45 mmol of FeCl3·6H2O and 1.24 mmol of the linker H2BDC were thoroughly dissolved in 30.0 mL of DMF. After, the solution was poured into a Teflon-lined autoclave, sealed, and subjected to thermal treatment at 120 °C (Heating rate 5 °C min-1 for 15 h. The synthesized sample was isolated from the supernatant via centrifugation. To remove any unreacted components and further purify the MIL, the washing procedure was accomplished three times with MeOH. Subsequently, the sample was dried in a vacuum oven at 100 °C.

Synthesis of GO

The GO applied in the preparation of the E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO composite NFs was synthesized utilizing a modified Hummers’ methodology, excluding sodium nitrate (NaNO3) from the reaction medium. Briefly, 3.0 g of graphite powder (325 mesh) was gradually added to 70.0 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) in a round-bottom flask under stirring in an ice bath. Upon increasing the agitation speed, 9.0 g of potassium permanganate (KMnO4) was slowly introduced into the mixture, which allowed the temperature to be maintained around 20 °C and assisted in controlling the reaction rate. The system was then transferred to a coil bath at 45 °C and stirred vigorously for 40 min. Next, 150.0 mL of deionized water was added to the solution and stirred at 95 °C for 20 min. After this period, an aliquot of 500.0 mL of water was introduced, followed promptly by 15.0 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%), which caused a color change from brown to pale yellow. The sample was vacuum-filtered and washed with 250.0 mL of 10% v/v HCl by centrifugation at 6000 rpm to eliminate metal ion impurities. In the final step, the sample was poured into Petri dishes and air-dried58,59.

Synthesis of E-spun PAN NFs and PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO composite NFs

A total of 0.3 g of PAN was dissolved in 2.0 mL of DMF. Separately, approximately 0.03 g of pre-synthesized MIL was dispersed in 1.0 mL of DMF and subjected to vigorous stirring for 2 h. Subsequently, 0.002 g of as-prepared GO was incorporated into the MIL dispersion. The contents of the second container were then incrementally added into the first, and the resulting mixture was continuously stirred at ambient temperature for 24 h to ensure the attainment of a uniform solution.

The prepared solution was loaded into a 5.0 mL syringe fitted with a 24-gauge flattened needle and subjected to electrospinning under optimized conditions: an applied voltage of 23.5 kV, a flow rate of 0.6 mL h−1, and a needle-to-collector distance of 11 cm.

It is noteworthy that the solution of pristine PAN NFs was fabricated using the identical procedure outlined for the first container, with the exception that 3.0 mL of DMF was utilized, and the electrospinning parameters were adjusted as follows: an applied voltage of 18.0 kV, a flow rate of 0.5 mL h−1, and a needle-to-collector distance of 9.5 cm.

Real sample pretreatment and microextraction procedure

TIWW real-samples collection and pre-treatment

TIWW samples were sampled from factories located in Qaem Shahr (Mazandaran Province) and Tajan (Astaneh-ye-Ashrafiyeh County, Gilan Province), Iran (pH 8.3–9.1, conductivity 2170–2905 µS cm−1). The samples were promptly transferred to the laboratory in sterile glass containers under controlled conditions and preserved at 4℃ to maintain their integrity for subsequent analytical analyses.

In brief, for sample pre-treatment, the supernatant was separated following centrifugation at 20℃ for 10 min at 9000 rpm, and thereafter passed through a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate syringe filter to ensure thorough clarification.

Microextraction procedure

The highly facile and user-friendly technique of TF-SPME was accomplished for the pre-concentration and adsorption of two intended dyes, MO and CR, from aqueous solution. In this procedure, 10.0 mL of a sample solution containing 2.0 mg L−1 of analytes at pH 6 was poured into a beaker and placed on a magnetic stirrer set to 500 rpm. A 1 cm × 1 cm segment of E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO composite NFs, supported on aluminum foil was excised and immersed into the solution using tweezers. Following an optimized adsorption period of 15 min, the adsorbent was carefully removed and transferred into a tube containing 1.0 mL of 0.5 M HCl solution. Desorption was facilitated through vortex agitation for 5 min. The desorbed analytes-containing solvent was subsequently loaded into a UV cell and analyzed via UV–Vis spectrophotometry.

UV–Vis spectra of MO and CR sample solutions (2.0 mg L⁻¹) were recorded before and after the prescribed extraction (Fig. S1). Prior to adsorption, the absorption bands at ~ 465 and ~ 501 nm for MO and CR, respectively, were barely discernible. Subsequent to extraction and desorption from the E-spun NF adsorbent, these characteristic bands were clearly restored with elevated intensity, manifesting efficient adsorption and preconcentration of the intended dyes.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the adsorbent materials

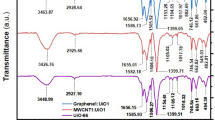

FTIR spectroscopy was applied to elucidate the functional groups present in the E-spun composite NFs and their respective constituents (Fig. 1). In the accompanying figure, stretching and bending vibrational modes are designated as ‘s’ and ‘b’, respectively. For GO, the key transmission peaks are as follows: 3267 cm−1 (O—H stretching vibration, with contributions from adsorbed water molecules), 1715 cm−1 (C=O stretching vibration in carboxylic groups), 1586 cm−1 (aromatic C=C stretching vibration), 865 cm−1 and 1162 cm−1 (epoxy C—O stretching vibration), and 1021 cm−1 (alkoxy C—O stretching vibration). The existence of oxygen-containing functional groups in GO was substantiated by the observed peaks60. In the E-spun PAN NFs, the distinctive peaks at 2935 cm−1, 2245 cm−1, 1455 cm−1, and 1066 cm−1 are ascribed to the symmetric and asymmetric C—H stretching vibrations (notably within methylene groups), the C≡N stretching vibration, the C—H bending vibration, and the C—C stretching vibration, respectively60. As apparent in the MIL-101(Fe) spectrum, the peaks at 3410 cm−1 and 1667 cm−1 are respectively assigned to the O—H stretching vibration and the C=O stretching vibration. The symmetric and asymmetric vibrations of O—C=O manifest at approximately 1389 cm−1 and 1593 cm−1, respectively, affirming the integration of the dicarboxylic acid linker within the MIL-101(Fe) structure. Further, the peaks observed at 1023 cm−1, 753 cm−1, and 534 cm−1 correspond to the bending vibration of C—O—C, the C—H bending vibration within the benzene ring, and the Fe—O stretching vibration, respectively. The resultant spectrum is in concordance with findings reported in the extant literature49.

The majority of the characteristic peaks corresponding to the aforementioned components were discerned and identified in the spectrum of the PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO composite NFs. Among these, the symmetric and asymmetric O—C=O stretching vibration peaks of MIL-101(Fe) (1392 and 1658 cm−1, respectively) are discernible, with the symmetric peak partially overlapping the C—C bending vibration of PAN, manifesting as a doublet. The peak, marginally shifted to 1724 cm−1, is assigned to the C=O functionality in both MIL-101(Fe) and GO, which are wholly superimposed due to the proximity of their wavenumbers. The broad peak detected from 950 to 1150 cm−1 is ascribed to the overlapping stretching vibrations of epoxy and alkoxy moieties in GO and of C—C in PAN. It merits noting that several GO and MIL peaks are not clearly identifiable in this spectrum, as expected given the preponderance of PAN in the E-spun composite NFs.

Several spectral features reflect interactions among the constituents. The C≡N peak in the composite NFs (2188–2263 cm−1, centered at 2240 cm−1) demonstrates subtle broadening and a red shift relative to the unmodified PAN NFs (2196–2265 cm−1, centered at 2244 cm−1). The main reason arises from Lewis acid–base coordination between this functionality and MIL, wherein the C≡N group acts as a Lewis base owing to its lone pair, while Fe+3 acts as a Lewis acid. Hydrogen bonding with oxygenated functionalities in GO may also contribute. The O—C=O vibrations, along with the slightly weaker C=O vibration, display minor shifts. The former pertains to MIL, while the latter involves both MIL and GO; these peaks are not observed in the spectrum of neat PAN NFs. Moreover, the 950–1150 cm−1 region exhibits altered patterns compared to the PAN NF spectrum, aligning with contributions from the additive functionalities within this range. These findings substantiate the successful synthesis of the composite NFs.

Moreover, the adsorption of the intended dyes onto the composite NFs was validated through post-adsorption FTIR spectral analysis, and the resulting spectra were subsequently compared (Fig. S2). The representative post-adsorption spectrum shows new peaks at 1215 and 1560 cm−1, corresponding to the stretching vibrations of sulfonate (S=O) and azo (N=N) moieties from both targeted dyes, respectively, indicating dye–adsorbent interactions. Additionally, reductions in the intensities of several characteristic peaks of composite NFs, specifically those related to O—H and C≡N groups, were observed, reflecting interactions with dye molecules via hydrogen bonding and electrostatic attraction. These results affirm the successful uptake of CR and MO61.

The crystalline structure of the prepared NFs was elucidated via PXRD analysis across a 2θ range of 0.1°–80°. Scrutiny of the resultant diffraction pattern (Fig. S3) reveals a sharp peak at 8.86°, corresponding to the interplanar spacing between graphene layers in GO62. The peak observed at 16.81° is ascribed to PAN, which predominates in the NF network63. An attenuated, broad feature in the approximately 20°–30° range, partially overlapping with the PAN 2θ region, has been outlined in previous literature on MIL-101(Fe)–based composite synthesis, albeit not expressly emphasized64. On the other hand, the distinct peaks at around 11°, 17°, and 20°, reported in some investigations65 are not evident here, presumably due to the low proportion of MIL-101(Fe) in the composite network.

The observations outlined above substantiate the semicrystalline architecture of the E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO composite NFs, in addition to affirming the fidelity of the synthesis procedure.

The structural morphology of the synthesized MIL-101(Fe), GO, and the various types of E-spun NFs was meticulously examined through FE-SEM imaging. Image (A) in Fig. 2 illustrates the pristine PAN NFs with a bead-free, smooth morphology and diameters spanning 132.5 nm to 238.1 nm. In (B), the octahedral structure of MIL particles is prominently depicted, characterized by smooth surfaces and well-defined edges. The resultant structural features are in full concordance with findings reported in previously published literature66. Further, the layered architecture of the synthesized GO particles is clearly inferred from Fig. 2 (C). As depicted in Fig. 2 (D and E), the integration of MIL-101(Fe) and GO into the PAN network has effectively reinstated the NF structure. Compared to (A), this modification induces minimal alterations to the overall morphology of the composite NFs. Additionally, it is noteworthy that there is a slight increase in the diameter of the adsorbent NFs, ranging from 225.3 nm to 308.7 nm, compared to the pure PAN NFs. This enlargement is likely attributed to the incorporation of the aforementioned materials, which facilitate the formation of new interactions within the composite structure.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and mapping analyses provide valuable insights into the elemental composition and its distribution across the certain surface of the E-spun adsorbent. As demonstrated by the data presented in Fig. 3, the iron content of 9.68% by weight substantiates the incorporation of MIL-101(Fe) within the composite adsorbent. Moreover, the mapping diagram clearly illustrates the homogeneous dispersion of all elements.

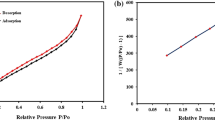

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption analysis at 77 K was performed to determine the adsorbent’s specific surface area (SSA) and pore size distribution (PSD) utilizing the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) and Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) techniques (Fig. 4). According to the IUPAC classification, the resultant isotherm (Fig. 4 (A)) corresponds to Type IV with a discernible H3 hysteresis loop, characteristic of mesoporous materials (2–50 nm). The observed hysteresis reflects capillary condensation within the slit-like pores formed by sheet-like GO and the porous framework of the MIL-101(Fe) structure. The PSD curve attained by BJH analysis (Fig. 4 (B)) further verified that the fabricated E-spun NFs fall within the mesoporous range, with a substantial fraction of pores below 20 nm. Moreover, BET and BJH analyses yielded a SSA of 21.48 m2 g−1, a total pore volume of 0.0438 cm3 g−1, and an average pore diameter of 20.82 nm.

Such a structure, featuring suitable porosity, mesopores, and interconnected pores, constitutes a promising adsorbent and facilitates the effective penetration of target molecules.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) quantitatively assesses moisture, residual solvents, and weight loss associated with thermal decomposition. PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO NFs were analyzed up to 700 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 under a nitrogen atmosphere with a flow rate of 10 mL min−1. In Fig. S4, the solid line represents the TGA curve and the dashed line its derivative. A minor weight loss of ~2.8% at 105 °C is ascribed to the removal of trapped solvents, primarily water and DMF. A pronounced weight loss of ~34.4% at an intermediate temperature of 302 °C is assigned to the pyrolytic decomposition of PAN, arising from thermally induced chemical reactions67. At this temperature, the polymer backbone undergoes breakdown, releasing volatile compounds such as ammonia and hydrogen cyanide. An additional weight loss observed at 390 °C is attributed to the combined decomposition of MIL-101(Fe) terephthalic acid linkers and the oxygen-containing functional moieties of GO, predominantly as CO and CO2. In the final stage, a relatively minor weight loss at 620 °C stems from the slow carbon degradation of PAN and GO residues.

This test provided insights into the thermal stability and degradation pathways potentially occurring at different temperature stages, enabling the tailored implementation of the fabricated NFs.

Point of zero charge (pHpzc) studies

To attain a deeper understanding of the interactions between the adsorbent and the dye molecules under investigation, a point of zero charge (pzc) analysis is deemed indispensable. The pHpzc signifies the pH at which the adsorbent’s net surface charge equals zero, effectively rendering it electrically neutral. In accordance with the “solid addition” protocol68, 10.0 mL aliquots of a 0.01 M NaCl solution were dispensed into glass vials. The pH of each vial was meticulously adjusted within the range of 4.0 to 10.0 (initial pH, pHi) by employing 0.10 M HCl and 0.10 M NaOH solutions. Adsorbent specimens, precisely sectioned into dimensions of 1 cm × 1 cm, were immersed in the prepared vials. The vials were securely sealed and subjected to continuous stirring on a magnetic stirrer under ambient conditions for 24 h. Following this period, the final pH (pHf) of each vial was recorded. A curve depicting the variation of ΔpH as a function of pHi was subsequently plotted. The intersection point at which ΔpH equals zero was identified as the pHpzc. As demonstrated in Fig. 5, the pHpzc of the synthesized E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO NFs is approximately 6.3. Below this pH threshold, the NFs possess a positive surface charge, attributable to the protonation of nitrile (-C≡N) functionalities within the polymer skeleton, carboxyl (-COOH), hydroxyl (-OH), and Fe–O moieties in the MIL structure, as well as the hydroxyl (-OH) and epoxide (–O–) functionalities on the GO basal plane. Conversely, at pH values exceeding 6.3, the deprotonation of hydroxyl and carboxyl groups imparts a negative surface charge to the NFs, thereby altering their electrostatic properties. It is paramount to note that the protonation of the functional moieties in the adsorbent constituents does not occur concurrently, but depends on each group’s inherent pKa and the solution pH.

Regarding the intended dyes, MO adopts an anionic form at neutral pH due to deprotonation of its sulfonic acid (R—SO3−) functionalities. CR, a diprotic acid with two pKa values (\(\:{\text{pK}}_{{\text{a}}_{\text{1}}}\)= 4.08 and \(\:{\text{pK}}_{{\text{a}}_{\text{2}}}\)= 11.43), primarily exists as the monoprotic HIn⁻ form within the pH span of 6.0–9.0. Hence, under the experimental pH of ≈ 6, both dyes carry a negative charge, in accordance with the anticipated electrostatic interactions based on the adsorbent’s resultant pHpzc.

pH stability of E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO composite NFs

The environment pH stands as a critical factor in sequestration approaches, while the stability of the adsorbent under these conditions is equally essential. Accordingly, its stability was appraised over a pH range of 1.0–11.0. Initially, defined weights of NF mat (Wi) were immersed in vials of pure water adjusted to the specified pH values at ambient temperature. After exposure for a prescribed duration (24 h), the samples were removed, dried, and their final weights (Wf) were recorded. The percentage of adsorbent loss was then calculated using the following equation:

Here, Wi and Wf represent the weights of the dried mat before and after immersion, respectively. The findings (Fig. S5) reveal an insignificant weight loss across a broad pH range, reflecting that the proposed adsorbent can adsorb and desorb the target dye molecules throughout this pH span without compromising its structural integrity.

Optimization

Optimizing the adsorbent conditions

The attainment of the optimal composition in the fabricated E-spun NFs was realized through the meticulous evaluation of key parameters, including the proportion of MIL-101(Fe), the amount of GO particles, and the selection of the adsorbent type.

MIL-101(Fe) amount. The amount of MIL-101(Fe) was optimized (while the GO amount remains constant at 0.001 g) by varying quantities of the compound ranging from 0.01 g to 0.05 g. As shown in Fig. S6 (A), after 0.03 g, the absorbance signal plateaued. Therefore, to conserve resources and reduce synthesis cost, 0.03 g was selected for subsequent steps.

GO amount. To achieve high adsorption performance with E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO NFs, two amounts of GO (0.001 g and 0.002 g) were examined. According to the attained results, incorporating 0.002 g of GO into the adsorbent improved the extractability, resulting in higher absorbance. However, increasing the GO content beyond the aforementioned amount required higher voltages during the electrospinning process and led to the formation of multiple droplets.

Adsorbent type. The extractability of PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO composite NFs was compared with the pristine PAN NFs and PAN/MIL-101(Fe) composite NFs to select the best adsorbent. As indicated in Fig. S6 (B), the most absorbance signals are related to the PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO composite NFs as the adsorbent. The incorporation of PAN with a mix of MIL-101(Fe) and GO led to improvement of signals 2.27-fold for MO and 2.54-fold for CR. The elevated performance of the PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO ternary system reflects the synergistic effect of its three constituents. Specifically, MIL-101(Fe) and GO increase the density of oxygen-containing functionalities, reinforcing interactions with the intended azo dyes, while GO boosts NF permeability and facilitates dye diffusion, thereby augmenting the adsorption capacity49.

Optimizing the TF-SPME conditions

To investigate the parameters affecting the TF-SPME procedure, several factors—including pH, sorbent size, sample volume, adsorption and desorption time, and eluent type and volume—were optimized through the one-at-a-time (OAT) technique, with 2.0 mg L−1 of the dyes applied at each step. The OAT methodology offers straightforward interpretation and practical application. Although it does not account for variable interactions, its reliability has been extensively validated32,69. Comparative investigations employing statistical designs have revealed that such interactions are either not significant70 or exert merely a limited influence on adsorption efficiency71.

pH. Since pH is one of the most influential factors affecting both the analytes and adsorbent structure, this parameter was tested in the range of 4.0 to 9.0 to determine the optimal value. At pH values beyond this range, owing to the changes in the surface charge of the adsorbent as well as the ionization state of the selected dye molecules, adverse effects on adsorption may occur. As shown in Fig. S7 (A), the absorbance signals for both target analytes increased with pH up to 6 and then decreased slightly beyond this value. At pH 6, considering the pHpzc of 6.3 for PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO, the adsorbent acquired a positive charge (δ+). Meanwhile, CR, with a \(\:{\text{pK}}_{{\text{a}}_{\text{1}}}\)of 4.0872, carried a negative charge, and MO, with a pKa of 3.5073, also obtained a negative charge at this pH. Consequently, at this optimal pH, π-π stacking, hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions contributed effectively to the adsorption process. Therefore, pH 6.0 was selected for the next steps. A comprehensive explanation of all the possible interactions between the adsorbent and adsorbates is provided in Section "Interaction mechanisms of two dyes uptake by E-spun NFs".

Sorbent size. To appraise the sorbent size of E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO in the extraction process, sheets of different sizes, including 0.5 × 0.5, 1 × 1, 1.5 × 1.5, 2 × 2, and 3 cm × 3 cm were investigated (Fig. S7 (B)). It is evident that the highest absorbance of the targeted dyes was attained with a 1 cm × 1 cm sorbent, after which it slightly decreased. An insufficient amount of adsorbent results in suboptimal extraction of the analytes. In contrast, an excessive amount not only elevates the procedure cost and eluent consumption but also amplifies environmental consequences owing to higher chemical usage. Moreover, larger eluent volumes cause dilution, thereby diminishing the preconcentration factor74. As a result, a 1 cm × 1 cm sorbent was utilized in subsequent experiments.

Sample volume. In order to determine the optimal sample volume based on the attained analytical signal, volumes of 5.0, 10.0, 15.0, 20.0, and 25.0 mL were tested. As seen in Fig. S7 (C), the signals increased in the initial range (5.0 mL–10.0 mL),which can be ascribed to greater analyte transfer to the adsorbent surface75. However, at volumes exceeding 10.0 mL, no discernible change was observed. Hence, ensuing experiments were conducted with 10.0 mL of the sample solution.

Adsorption time. In light of the time-dependent nature of mass transfer during extraction, the efficacy of the process is governed by the duration of adsorbent-adsorbate contact. To evaluate this parameter while preserving time economy, adsorption periods of 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 min were tested. According to the results in Fig. S7 (D), the absorption signals enhanced up to 15 min, after which no appreciable change was observed, reflecting the attainment of equilibrium. Accordingly, 15 min was designated as the optimal adsorption time.

Desorption time. Given the deeply time-dependent inherent of mass transfer in desorption duration, different time intervals from 1 to 9 min were selected to examine. The results, as shown in Fig. S8 (A), revealed that the highest absorbances were for 5 min desorption time, after which they slightly decreased. Consequently, 5 min was applied for the following experiments.

Eluent type. With the aim of examining the eluent type, which is one of the outstanding parameters affecting extractability, various solvents such as ACN, EtOH, 0.5 M HCl, MeOH, MeOH/HOAc5%, and EtOH/HOAc5% were analyzed. The obtained data (Fig. S8 (B)) demonstrate that the best absorbances were gained with 0.5 M HCl. Since MO and CR are anionic dyes, exposure to acidic solvents can neutralize the dye molecules, making desorption from the adsorbent surface easier due to weaker electrostatic interactions between the dyes and the adsorbent. Additionally, using HCl as an eluent solvent can compete with the dyes for active sites on the adsorbent, allowing HCl to be absorbed and thereby displacing the dye molecules.

Eluent volume. Eluent volume is another parameter that must be optimized. It should neither be excessively low, which would hinder the complete release of analytes from the adsorbent surface, nor excessively high, which would lead to a dilution effect in the sample solution and ultimately reduce the absorbance signals. Therefore, five different eluent volumes of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 mL were consumed. According to the results illustrated in Fig. S8 (C), the highest absorbances were obtained with 1.0 mL of eluent, and beyond this volume, the absorbance signal of the analytes decreased. Eventually, 1.0 mL was selected.

Batch adsorption of dyes onto prepared E-spun NFs

Adsorption capacity

The adsorption capacity of E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO NFs was investigated by immersing 1 cm × 1 cm dimensions of the adsorbent into solutions of target dyes with concentrations ranging from 1.0 to 80.0 mg L−1. After performing this procedure for 2 h under optimized conditions, the adsorbent was removed from the sample solution and the absorbance was measured. Eventually, the amount of equilibrium adsorption capacity (Qe (mg g−1)) was calculated through Eq. (2), where Ci (mg L−1) and Ce (mg L−1) display the initial and equilibrium concentrations of analytes, respectively, V (L) is the sample volume, and m (g) illustrates the dry adsorbent weight.

According to the gained results (Fig. S9), the equilibrium adsorption capacities of the adsorbent for MO and CR were 108.015 mg g−1 and 102.704 mg g−1, respectively.

Adsorption isotherms study

The interaction between the adsorbent and adsorbate was investigated utilizing adsorption isotherms at room temperature (25 °C). In this study, the Langmuir, Temkin, and Freundlich adsorption isotherm models were examined as detailed below:

The Langmuir adsorption isotherm Eq. (3):

The Temkin adsorption isotherm Eq. (4):

The Freundlich adsorption isotherm Eq. (5):

Where Ce (mg L−1) is the equilibrium concentration, Qe (mg g−1) is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium, Qm (mg g−1) is the maximum adsorption capacity, KL (L mg−1) is the Langmuir constant, B is related to the heat of adsorption, KT (L g−1) is the Temkin constant, n is the Freundlich intensity, and KF ((mg g−1)(L mg−1)1/n) is the Freundlich constant. The separation constant (RL, Eq. (3)) is a key parameter obtained from the Langmuir model, its magnitude reflecting the favorability of adsorption. In particular, RL > 1 denotes unfavorable adsorption, RL = 1 reflects linear adsorption, and RL = 0 indicates irreversible adsorption, whereas values within the range 0 < RL < 1 evince favorable adsorption. In Eq. (4), derived from the Temkin model, B represents a constant associated with the adsorption heat. It is proportional to the universal gas constant (R = 8.314 J mol−1 K−1), the absolute temperature (T, K), and the Temkin constant (bT, J mol−1). In the Freundlich model (Eq. (5)), 1/n designates the heterogeneity factor, whereas the dimensionless constant n corresponds to the adsorption intensity. Hence, values of n falling within the interval 2–10 manifest the favorability of the adsorption procedure.

Based on the data presented in Table S1 and the results illustrated in Figs. S10-S12, the Langmuir adsorption isotherm yielded the highest R2 values (0.9859 for MO and 0.9788 for CR) and provided the best fit. This indicates that the adsorption of MO and CR on the PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO NFs adsorbent occurs predominantly as a monolayer on energetically equivalent adsorption sites, consistent with the Langmuir assumptions76.

The calculated RL values (0.0237–0.7134) reveal that the adsorption process on the composite NFs is favorable. Moreover, the average n value of 4.49 authenticates the favorable nature of the adsorption. The bT values compiled in Table S1 are below 20 kJ mol−1, illustrating that the adsorption of the intended azo dyes onto the adsorbent mat occurs predominantly via physisorption69.

Adsorption kinetics study

The adsorption kinetics of two anionic azo dyes onto the PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO adsorbent were evaluated by analyzing the pseudo-first-order (PFO), pseudo-second-order (PSO), and intraparticle diffusion (IPD) kinetic models.

The pseudo-first-order Eq. (6):

The pseudo-second-order Eq. (7):

Where Qe (mg g−1) and Qt (mg g−1) represent the adsorption capacity at equilibrium and at time t, respectively. K1 (min−1) is the rate constant of the PFO model, t (min) is the adsorption time, and k2 (g mg−1 min−1) is the rate constant of the PSO model. The parameter k2Qe2 in Eq. (7) denotes the maximum rate at which the analytes are adsorbed onto the adsorbent. The calculated values, spanning 1.2096–1.5746 mg g−1 min−1, are represented by the notation ‘h’ in Table S2. Equation (7) also enables the determination of t1/2, the reciprocal of h (t1/2 = 1/k2Qe2), which defines the time required for adsorption of half the equilibrium concentration of dyes. The computed t1/2 quantities, ranging from 0.6351 to 0.8267 min, are listed in Table S2.

The PFO and PSO kinetic models (Fig. S13) are incapable of clarifying the diffusion mechanism and identifying the rate-controlling step of analyte molecules within the composite NF adsorbent77. For this purpose, the intraparticle diffusion (IPD) model was applied, and the respective kinetic curves were plotted. The model is expressed by Eq. (8):

where kid denotes the intraparticle diffusion rate constant (mg g−1 min −0.5), t0.5 is the square root of time (min0.5), and C is a constant (mg g−1) associated with the boundary layer thickness.

The findings (Fig. S14) unambiguously manifest three discrete regions in the dye adsorption behavior onto the composite NFs. The marked multi-linearity and non-zero intercept from the origin provide evidence that intraparticle diffusion is not the sole rate-controlling mechanism69.

Considering the data compiled in Table S3, Region I, corresponding to external surface diffusion, is approximately identical for both dyes, with kid values of 9.24–9.50, illustrating a comparable boundary layer influence on their adsorption rate. In Region II, characterizing intraparticle diffusion, MO demonstrates slightly faster diffusion into the adsorbent pores than CR (5.83 vs. 4.08), arising from the greater molecular dimensions or stronger adsorbent–molecule interactions32. In Region III, the equilibrium phase, the kid value for MO is marginally higher than that for CR (13.96 vs. 11.26), likely due to the more efficient diffusion of MO molecules, as previously corroborated by the results from Region II. It is noteworthy that the salient boundary layer resistance affecting the intraparticle diffusion of the CR analyte leads to a C parameter with higher positivity in Region II (Table S3).

Based on the kinetic data (Tables S2 and S3) and corresponding results (Figs. S13 and S14), the PFO model demonstrates a more accurate representation of the adsorption mechanism than the other models, with satisfactory R2 values (0.9334 for MO and 0.9831 for CR). The substantial consistency between the calculated (Qe, cal) and experimental (Qe, exp) adsorption capacities further underscores the preeminence of the PFO model, therefore, the adsorption procedure is chiefly dictated by physisorption. The correlation in Region I of the IPD model (R2 = 0.9080 for MO and 0.9140 for CR) supports a physisorption-dominated mechanism30.

In conclusion, the combination of multi-stage mass transfer, as evidenced by the IPD model, and the aforesaid low-energy, reversible interactions rationalize the better fit of the adsorption data to the PFO model over the PSO model.

Interaction mechanisms of two dyes uptake by E-spun NFs

The adsorption mechanisms of dyes onto the NF mat can generally be delineated into three sequential stages: the diffusion stage, during which dye molecules traverse toward the surface layer of the film; the gradual adsorption stage, marked by the progressive occupation of active adsorption sites; and the equilibrium stage, wherein the majority of the active sites become saturated with dye molecules78. Furthermore, to provide a comprehensive interpretation of the adsorption behavior, the experimental data were fitted to isotherm and kinetic models, as elaborated in Section "Batch adsorption of dyes onto prepared E-spun NFs". The Langmuir isotherm, which best fitted the experimental data (R2 = 0.9859–0.9788), demonstrated monolayer adsorption on the surface of composite NFs with equivalent active sites. RL values within the suitable range (0.0237–0.7134), n values (4.19–4.79), and bT data (139.6681–161.3738 J mol−1), calculated from the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin isotherm models, cumulatively corroborate the favorability and dominance of physical adsorption between the prepared composite NFs and targeted azo dyes. Kinetic examinations show that the R2 values (0.9334–0.9831) from the PFO model, along with the close agreement between Qe,cal (112.776–112.426 mg g−1) and Qe,exp (108.015–102.704 mg g−1), reflect the involvement of physical adsorption mediated by non-covalent interactions69.

To acquire spectral evidence, the FTIR spectrum of the adsorbent was recorded after dye adsorption (Fig. S2). Dye-associated peaks were discernible, while neither the composite’s inherent functional groups nor newly emerging ones revealed any discernible wavenumber shifts, suggesting that adsorption was mainly physical. The relative attenuation of certain peaks is probably attributable to the binding of dye molecules to the adsorbent surface. Figure 6 schematically illustrates the plausible interaction mechanism between the adsorbent constituents and the intended adsorbates.

The existence of diverse functional moieties, including nitrile (-C≡N) groups in the polymer backbone, carboxyl (-COOH) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups in the MIL and GO components, as well as epoxide (–O–) linkages on the GO surface, collectively enables the deduction of the adsorption mechanisms of MO and CR onto the E-spun NFs. Taking into account the pKa values of the dyes (MO = 3.50 and \(\:{\text{pK}}_{{\text{a}}_{\text{1}}}\)for CR = 4.08), the pHpzc value of the NFs (approximately 6.3), and the optimal pH (6.0) at which the adsorption process occurs, it can be inferred that both dye molecules are negatively charged, while the adsorbent carries a partial positive charge. Therefore, the adsorption mechanism is primarily driven by non-covalent electrostatic interactions. At pH = 6.0, the positive surface charge of the NFs induces a robust electrostatic attraction with the anionic sulfonate groups (-SO3⁻) present in both MO and CR dye species. The two primary constituents of the NFs, MIL and GO, both enriched with aromatic and conjugated structures, act as active sites for π-π stacking interactions. These interactions occur between the aromatic rings of the dye molecules and the delocalized π-electrons within these components. Additionally, H atoms on the surface of the PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO NFs interact via hydrogen bonding with the N, O, and S atoms in the targeted anionic dyes. Notably, this latter interaction, involving the oxygen-bearing functional groups of the adsorbent—such as -COOH and -OH moieties—and the organic species of the dyes, is particularly pronounced and energetically favorable.

Accordingly, the adsorption mechanisms of adsorbates onto the PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO NFs is predominantly dictated by physisorption, encompassing a complex interplay of electrostatic interactions, π-π stacking, and hydrogen bonding. The multifaceted interactions among the PAN, MIL, and GO components synergistically elevate the overall adsorption performance, rendering the synthesized NFs highly proficient at sequestering anionic dyes from aqueous environments.

Method validation

To assess the performance characteristics of the TF-SPME/UV-Vis methodology utilizing E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO NFs for the quantification of MO and CR, key parameters—including the limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), linear dynamic range (LDR), enrichment factor (EF), extraction recovery percentage (ER%), and relative standard deviation percentage (RSD%)—were determined under optimized conditions.

As displayed in Table 1, the LOD (S/N = 3) was determined to be 0.017 mg L−1 for MO and 0.026 mg L−1 for CR, while the LOQ (S/N = 10) was found to be 0.05 mg L−1. The LDR ranged from 0.05 mg L−1 to 3.0 mg L−1 for each analyte, with R2 values of 0.9952 for MO and 0.9982 for CR. Moreover, the within-day RSD% (n = 5) spanned from 3.20% to 4.04% for MO and 2.69 to 4.38% for CR, illustrating the desirable precision of the developed procedure. The EF, computed as the ratio of the extraction calibration slope to the direct calibration slope, yielded values of 8.11 for MO and 8.06 for CR.

In addition, ER% was calculated using Eq. (9), where VEluent is the volume of the elution solvent and VSample represents the volume of the sample solution, resulting in values of 81.06% for MO and 80.63% for CR.

Reusability study

Considering its crucial environmental and economic implications, the reusability of the PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO adsorbent was systematically evaluated by monitoring the extraction efficiency of the target analytes over 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 15 adsorption–desorption cycles. The experimental conditions encompassed an adsorbent size of 1 cm × 1 cm, 10.0 mL of intended azo dye solution at an initial concentration of 2.0 mg L−1, an optimal pH of 6.0, 15 min adsorption time, and 5 min desorption time employing 1.0 mL of 0.5 M HCl as the eluent. Subsequent to each adsorption–desorption cycle, the utilized adsorbent was thoroughly rinsed with a 50:50 v/v water/MeOH mixture. As depicted in Fig. S15, after 15 cycles, the extraction efficiency showed a slight decline from 96.08% to 93.72% for MO and from 94.19% to 90.59% for CR, representing an insignificant loss in efficiency (less than 5%).

Applicability of the suggested method in real samples analysis and matrix effect assessment

The performance of the proposed TF-SPME/UV-Vis methodology, employing the fabricated E-spun NF-based adsorbent, was explored for the quantification of two intended dyes in TIWW samples, both unspiked and spiked at three distinct concentration levels. As elucidated by the data listed in Table 2, varying concentrations of the dyes were detected in the wastewater samples. The calculated RR% values (Eq. (10)) ranged from 89.00% to 102.50%, with RSD% values spanning from 3.17% to 5.04%, underscoring the method’s reliability and precision.

In the above equation, Cfound, Creal, and Cadded demonstrate the concentration of dyes in the spiked real sample, the concentration of dyes in the unspiked real sample, and the concentration of a certain standard amount added to the real sample, respectively.

Given the potential impact of the intricate matrix of TIWWs on the accurate quantification of dyes—manifesting as either enhancement or suppression effects—it is imperative to assess the matrix effect percentage (ME%). This parameter is determined by Eq. (11):

Where As and An are the absorbances of the target dyes in the spiked and unspiked real samples, respectively, and Aw indicates their absorbances in the spiked pure water. The calculated ME% values fall between 84.30% and 95.38% (Table 2). The findings substantiate the high efficacy of the developed E-spun NF-based TF-SPME/UV-Vis technique in providing reliable analysis of real-world samples, while also demonstrating solid performance in mitigating the influence of interfering compounds in complex matrices.

Comparison with other previously reported methods

Several parameters pertaining to the extraction protocol, along with pivotal analytical attributes, have been compiled and tabulated in Table 3 to facilitate a comprehensive comparison between the proposed TF-SPME/UV-Vis methodology and those described in prior literature79,80,81,82. A salient observation is that the most established procedures rely on HPLC-PDA instrumentation for the qualitative and quantitative analyses of the intended dyes. While acclaimed for their sensitivity, such systems entail labor-intensive, multi-step workflows, incur elevated operational expenditures, and generate substantially more waste compared to UV-Vis spectrophotometry. The UV-Vis technique features a streamlined procedure with minimal steps, enabling the expeditious acquisition of results. It is exceptionally user-friendly, economically advantageous, and, most importantly, environmentally sustainable owing to substantially reduced waste generation and the elimination of reliance on costly consumables. Moreover, despite the widespread application of HPLC-PDA instrumentation in the methodologies referenced in Table 3, the proposed TF-SPME/UV-Vis approach exhibits superior analytical sensitivity, as reflected by its lower LOD and LOQ values relative to the majority of the listed methods.

A notable merit of this research is the remarkably small quantity of adsorbent required, which, in conjunction with its commendable reusability, is sufficient for at least 15 adsorption/desorption cycles. This attribute aligns seamlessly with the tenets of green analytical chemistry (GAC), underscoring its environmental sustainability and operational efficacy. Although the research presented in the fourth row of Table 3 obtained a lower LOD compared to the TF-SPME/UV-Vis protocol, it necessitates the use of a larger amount of adsorbent. Unlike the TF-SPME/UV-Vis method, recognized for its operational simplicity and ease of handling, the method in question faces challenges in the efficient and thorough separation of adsorbent particles from the sample solution. Moreover, some reported adsorbents manifest relatively higher Qm values; however, their adsorption process is markedly slower, and isolating powdered adsorbents necessitates additional high-speed centrifugation (10,000 rpm), thereby contributing to methodological complexity.

Upon an in-depth comparison of the methodologies presented in the table, it can be reasonably inferred that the proposed TF-SPME/UV-Vis procedure, utilizing E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO NFs as the adsorbent, constitutes a straightforward, user-friendly, and robust analytical approach. It demonstrates notable reproducibility and sensitivity, while concurrently generating less analytical waste. Consequently, it may serve as a dependable technique for the determination of MO and CR anionic dyes in various water samples.

Practical limitations and cost estimate

Analogous to all adsorption procedures, the adsorbent proposed in this study is accompanied by certain inevitable limitations. Repeated utilization across successive adsorption–desorption cycles can provoke irreversible saturation of the adsorbent’s active sites and induce deterioration of the nanofibrous network, ultimately diminishing its operational durability. Exposure to harsh acidic or basic media induces the breakdown of intercomponent bonds within the adsorbent’s architecture, culminating in structural disruption, impaired efficacy, and compromised reusability. However, the fabricated E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO composite NFs manifested efficient extractability in environments with pH 4–9, maintained structural integrity, and yielded satisfactory analytical signals.

Alternatively, despite the high adsorbent efficacy attested in TIWWs, real-world sample matrices often harbor various contaminants with the potential to compete with target dyes for the adsorbent’s active sites, thus undermining analytical accuracy32,69. Notwithstanding the aforesaid issues, the suggested E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO NFs in this research possess a suite of benefits, comprising a robust skeletal structure conferred by the integration of MIL-101(Fe) and GO sheets, favorable adsorption capacity at elevated concentrations, porosity, and sustained reusability over successive cycles, jointly alleviating these constraints.

An essential determinant for the practical implementation and development of laboratory-scale adsorbents is their economic feasibility, which can be ascertained by estimating the material cost per unit mass used in the fabrication process. This analogy assumes comparable operating costs and recovery efficacies across all adsorbents. The evaluation is informative, as it is conducted on a per-gram basis of adsorbate uptake, thereby accounting for adsorption capacity69. The equation below (Eq. (12)) enables cost estimation with extrapolation for industrial-scale purposes.

In the above equation, AC and Q are the adsorption cost per gram of adsorbate and the adsorption capacity (mg g-1), respectively. Considering the cost of all materials and solvents, as well as applying Eq. (12) with a maximal adsorption capacity of 108.015 mg g-1, the cost of the synthesized composite adsorbent per gram of adsorbate was estimated at $0.33. This value does not account for the number of consecutive cycles a single adsorbent piece can be subjected to. The combination of affordable cost, reusability, and satisfactory adsorption capacity toward MO and CR azo dyes renders the E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO composite NFs a promising adsorbent for routine dye analysis.

Conclusions

In summary, an E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO composite NF mat was successfully fabricated through a streamlined and resource-efficient protocol. This adsorbent efficiently extracts MO and CR anionic dyes from TIWWs in TF-SPME/UV-Vis format. It exhibited desirable adsorption performance, with maximum capacities of 108.015 mg g−1 and 102.704 mg g−1 for MO and CR, respectively. Other benefits, including a satisfactory SSA (21.48 m2 g−1) and total pore volume (0.0438 cm3 g−1), along with robust physicochemical stability and reusability (< 5% loss after 15 cycles), support its practical applicability in real TIWW matrices, with high RR% values of 89.00–102.50%. The synergistic incorporation of GO and MIL-101(Fe) within the NF networks increased the abundance of oxygen-containing functionalities and strengthened π-π interactions, thereby augmenting the adsorbent’s affinity for dyes.

The straightforward and thorough separation of the adsorbent using tweezers streamlined the procedure, enhanced user-friendliness, and reduced time inefficiencies. Isotherm and kinetic studies revealed that the adsorption behavior of these analytes onto the NFs is best described by the Langmuir isotherm and the PFO kinetic models. These findings reflect the potential of the proposed E-spun NFs as a scalable and environmentally sustainable adsorbent for routine quantification of the selected dyes.

Despite the noted strengths, the proposed E-spun PAN/MIL-101(Fe)/GO composite NF-based TF-SPME/UV-Vis approach has certain limitations. The primary limitation is the lack of a suitable interface for coupling the TF-SPME setup with analytical instruments, which hampers automation. Another constraint is the employment of high voltage during NF fabrication, which raises safety concerns. Given its low estimated production cost (≈$0.33 per gram of adsorbate), future investigations should assess its applicability to other pollutants and complex real-world matrices, explore the feasibility of commercial-scale fabrication, and develop a suitable TF-SPME interface to enable automation.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its Supplementary Information file. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Shabir, M. et al. A review on recent advances in the treatment of dye-polluted wastewater. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 112, 1–19 (2022).

Oladipo, A. A. & Gazi, M. Uptake of Ni2 + and Rhodamine B by nano-hydroxyapatite/alginate composite beads: batch and continuous-flow systems. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 98 (2), 189–203 (2016).

Mosaffa, E., Ramsheh, N. A., Patel, D., Oroujzadeh, M. & Banerjee, A. Textile industrial wastewater treatment using eco-friendly Kigelia fibrous biochar: column and batch approaches. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 194, 555–571 (2025).

Umamaheswari, C., Lakshmanan, A. & Nagarajan, N. S. Green synthesis, characterization and catalytic degradation studies of gold nanoparticles against congo red and Methyl orange. J. Photochem. Photobiol B Biol. 178, 33–39 (2018).

Al-Tohamy, R. et al. A critical review on the treatment of dye-containing wastewater: ecotoxicological and health concerns of textile dyes and possible remediation approaches for environmental safety. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 231, 113160 (2022).

Oladipo, A. A., Ifebajo, A. O., Nisar, N. & Ajayi, O. A. High-performance magnetic chicken bone-based Biochar for efficient removal of rhodamine-B dye and tetracycline: competitive sorption analysis. Water Sci. Technol. 76 (2), 373–385 (2017).

Liu, W. et al. Magnesium ferrite as a dispersive solid-phase extraction sorbent for the determination of organic pollutants using spectrophotometry. J. Mol. Liq. 382, 121969 (2023).

Thevenon, F., Alabaster, G., Shantz, A. & Johnston, R. Progress on the proportion of domestic and industrial wastewater flows safely treated. World Health Org. pp. 81–96. (2024).

Kant, R. & Kant, R. Textile dyeing industry an environmental hazard. Nat. Sci. 4 (1), 22–26 (2011).

Islas, G. et al. Simple and efficient removal of Azo dyes from water samples by dispersive solid-phase micro-extraction employing graphene oxide with high oxygen content. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 105 (5), 1172–1184 (2025).

Chacko, J. & Kalidass, S. Enzymatic degradation of Azo Dyes – A review enzymatic degradation of Azo Dyes – A review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 1, 1250–1260 (2014).

Shabbir, R. et al. Highly efficient removal of congo red and Methyl orange by using petal-like Fe-Mg layered double hydroxide. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 102 (5), 1060–1077 (2022).

Kishor, R. et al. Degradation mechanism and toxicity reduction of Methyl orange dye by a newly isolated bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa MZ520730. J. Water Process. Eng. 43, 102300 (2021).

Firmino, H. C. T. et al. High-Efficiency adsorption removal of congo red dye from water using magnetic NiFe2O4 nanofibers: an efficient adsorbent. Mater 18 (4), 754 (2025).

Liang, N. et al. Ionic liquid-based dispersive liquid-liquid Microextraction combined with functionalized magnetic nanoparticle solid-phase extraction for determination of industrial dyes in water. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 1–9 (2017).

Ullah, J. K., Ashraf, M. S., Tariq, K. A. & Iqbal, S. Nanoparticle-Mediated remediation of wastewater contaminants: an inclusive analysis of glyphosate, congo red and Methyl orange. J. Mol. Struct. 1321 (4), 140127 (2025).

He, Y., Grieser, F. & Ashokkumar, M. The mechanism of sonophotocatalytic degradation of Methyl orange and its products in aqueous solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 18 (5), 974–980 (2011).

Victor, H., Ganda, V., Kiranadi, B. & Pinontoan, R. Metabolite identification from biodegradation of congo red by Pichia Sp. KnE Life Sci. 20, 102–110 (2020).

Ghattavi, S. & Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. GC-MASS detection of Methyl orange degradation intermediates by AgBr/g-C3N4: experimental design, bandgap study, and characterization of the catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 45 (46), 24636–24656 (2020).

Islam, S. U. et al. Ecofriendly blue emissive ZnO-graphene nanocomposite and its application as superior catalytic reduction of Methyl orange and congo red. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 108 (2), 411–422 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. High efficiency reductive degradation of a wide range of Azo dyes by SiO2-Co core-shell nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 199, 504–513 (2016).

Shojaei, S., Rahmani, M., Khajeh, M. & Abbasian, A. R. Ultrasound assisted based solid phase extraction for the preconcentration and spectrophotometric determination of malachite green and methylene blue in water samples. Arab. J. Chem. 16 (8), 104868 (2023).

Guo, Y., Liu, C., Ye, R. & Duan, Q. Advances on water quality detection by UV-Vis spectroscopy. Appl. Sci. 10 (19), 6874 (2020).

Oladipo, A. A. & Ifebajo, A. O. Highly efficient magnetic chicken bone Biochar for removal of Tetracycline and fluorescent dye from wastewater: Two-stage adsorber analysis. J. Environ. Manage. 209, 9–16 (2018).

Oladipo, A. A. & Gazi, M. Enhanced removal of crystal Violet by low cost alginate/acid activated bentonite composite beads: optimization and modelling using non-linear regression technique. J. Water Process. Eng. 2, 43–52 (2014).

Khan, W. A., Varanusupakul, P., Haq, H. U., Arain, M. B. & Boczkaj, G. Applications of nanosorbents in dispersive solid phase extraction/microextraction approaches for monitoring of synthetic dyes in various types of samples: A review. Microchem J. 208, 112419 (2025).

Zayed, A. M., Wahed, A., Mohamed, M. S. M., Sillanpää, M. & E. A. & Insights on the role of organic matters of some Egyptian clays in Methyl orange adsorption: isotherm and kinetic studies. Appl. Clay Sci. 166, 49–60 (2018).

Muhtar, S. A. et al. Complex mixture dye removal using natural zeolite modified polyacrylonitrile/polyvinylidene fluoride (Ze-PAN/PVDF) composite nanofiber membrane via vacuum filtration technique. Mater. Today Commun. 42, 111357 (2025).

Al-Omari, M. H. et al. Optimized congo red dye adsorption using ZnCuCr-Based MOF for sustainable wastewater treatment. Langmuir 41 (9), 5947–5961 (2025).

Mosaffa, E. et al. Bacterial cellulose microfiber reinforced Hollow Chitosan beads decorated with cross-linked melamine plates for the removal of the congo red. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 254, 127794 (2024).

Abdulhameed, A. S. et al. Polymeric nanocomposite adsorbent of Cross-linked Chitosan-adipic acid and SnO2 nanoparticles for adsorption of Methyl orange dye: isotherms, kinetics, and response surface methodology. J. Polym. Environ. 33 (2), 1086–1105 (2025).

Mosaffa, E. et al. Bioinspired chitosan/pva beads cross-linked with LTH-doped bacterial cellulose hydrochar for high-efficiency removal of antibiotics. Int J. Biol. Macromol 306, 141522–141540 (2025).

Mosaffa, E., Patel, R. I., Purohit, A. M., Basak, B. B. & Banerjee, A. Efficient decontamination of cationic dyes from synthetic textile wastewater using Poly(acrylic acid) Composite Containing Amino Functionalized Biochar: A Mechanism Kinetic and Isotherm Study. J. Polym. Environ. 31, 2486–2503 (2023).

Oladipo, A. A., Gazi, M. & Yilmaz, E. Single and binary adsorption of Azo and anthraquinone dyes by chitosan-based hydrogel: selectivity factor and Box-Behnken process design. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 104, 264–279 (2015).

Ngwabebhoh, F. A., Gazi, M. & Oladipo, A. A. Adsorptive removal of multi-azo dye from aqueous phase using a semi-IPN superabsorbent chitosan-starch hydrogel. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 112, 274–288 (2016).

Wen, Z. et al. Three-dimensional porous adsorbent based on chitosan-alginate-cellulose sponge for selective and efficient removal of anionic dyes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11 (5), 110831 (2023).

Narayan, M., Sadasivam, R., Packirisamy, G. & Pichiah, S. Electrospun polyacrylonitrile-Moringa olifera based nanofibrous bio-sorbent for remediation of congo red dye. J. Environ. Manage. 317, 115294 (2022).

Amini, S., Kandeh, S. H., Ebrahimzadeh, H. & Khodayari, P. Electrospun composite nanofibers modified with silver nanoparticles for extraction of trace heavy metals from water and rice samples: an highly efficient and reproducible sorbent. Food Chem. 420, 136122 (2023).

Aziziyan, R., Ebrahimzadeh, H. & Nejabati, F. Simultaneous determination of trace amounts of dopamine and uric acid in human plasma samples with novel voltammetric biosensor (GCE/Ppy/DEA MIP) following the thin film-µSPE method based on electrospun nanofibers. Microchem J. 194, 109235 (2023).

Liu, R. et al. Progress of Fabrication and Applications of Electrospun Hierarchically Porous Nanofibers. Adv. Fiber Mater. 4 (4), 604–630 (2022). (2022).

Wang, P. et al. Surface engineering via self-assembly on PEDOT: PSS fibers: biomimetic fluff-like morphology and sensing application. Chem. Eng. J. 425, 131551 (2021).

Cheng, N. et al. Nanosphere-structured hierarchically porous PVDF-HFP fabric for passive daytime radiative cooling via one-step water vapor-induced phase separation. Chem. Eng. J. 460, 141581 (2023).

Hasan, M. M. et al. Scalable fabrication of MXene-PVDF nanocomposite triboelectric fibers via thermal drawing. Small 19 (6), 2206107 (2023).

Nasir, A. M. et al. Recent progress on fabrication and application of electrospun nanofibrous photocatalytic membranes for wastewater treatment: A review. J. Water Process. Eng. 40, 101878 (2021).

Khodayari, P., Jalilian, N., Ebrahimzadeh, H. & Amini, S. Electrospun cellulose acetate /polyacrylonitrile /thymol /Mg-metal organic framework nanofibers as efficient sorbent for pipette-tip micro-solid phase extraction of anti-cancer drugs. React. Funct. Polym. 173, 105217 (2022).

Oleiwi, A. H., Jabur, A. R. & Alsalhy, Q. F. Electrospinning technology in water treatment applications: review Article. Desalin. Water Treat. 322, 101175 (2025).

Matysiak, W., Tański, T. & Smok, W. Electrospinning of PAN and composite PAN-GO nanofibres. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 91 (1), 18–26 (2018).

Khalili, R., Sabzehmeidani, M. M., Parvinnia, M. & Ghaedi, M. Removal of hexavalent chromium ions and mixture dyes by electrospun pan/graphene oxide nanofiber decorated with bimetallic nickel–iron LDH. Environ. Nanatechnol. Monit. Manag. 18, 100750 (2022).

Liu, Z., He, W., Zhang, Q., Shapour, H. & Bakhtari, M. F. Preparation of a GO/MIL-101(Fe) composite for the removal of Methyl orange from aqueous solution. ACS Omega. 6 (7), 4597–4608 (2021).

Lee, J., Yoon, J., Kim, J. H., Lee, T. & Byun, H. Electrospun PAN–GO composite nanofibers as water purification membranes. J Appl. Polym. Sci 135 (7), 45858 (2018).

Zhang, X., Zhang, S., Tang, Y., Huang, X. & Pang, H. Recent advances and challenges of metal–organic framework/graphene-based composites. Compos. Part. B Eng. 230, 109532 (2022).

Jafarian, H. et al. Synthesis of heterogeneous metal organic Framework-Graphene oxide nanocomposite membranes for water treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 455, 140851 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. Robust porous PAN-MIL-101(Fe) nanofiber composite membranes for highly selective phosphate removal and recovery from water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 375, 133741 (2025).

Karimiyan, H., Uheida, A., Hadjmohammadi, M., Moein, M. M. & Abdel-Rehim, M. Polyacrylonitrile / graphene oxide nanofibers for packed sorbent Microextraction of drugs and their metabolites from human plasma samples. Talanta 201, 474–479 (2019).

Cardoso, A. T., Martins, R. O. & Lanças, F. M. Advances and applications of hybrid Graphene-Based materials as sorbents for solid phase Microextraction techniques. Mol 29 (15), 3661 (2024).

Huang, Z. et al. Electrospun graphene oxide/MIL-101(Fe)/poly(acrylonitrile-co-maleic acid) nanofiber: A high-efficient and reusable integrated photocatalytic adsorbents for removal of dye pollutant from water samples. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 597, 196–205 (2021).

Skobelev, I. Y., Sorokin, A. B., Kovalenko, K. A., Fedin, V. P. & Kholdeeva, O. A. Solvent-free allylic oxidation of alkenes with O2 mediated by Fe- and Cr-MIL-101. J. Catal. 298, 61–69 (2013).

Chen, J., Yao, B., Li, C. & Shi, G. An improved hummers method for eco-friendly synthesis of graphene oxide. Carbon N Y. 64 (1), 225–229 (2013).

Lozano, N. M., Reynoso, F. P. & Gutiérrez, C. G. Eco-Friendly approach for graphene oxide synthesis by modified hummers method. Materials 15 (20), 7228 (2022).

Ahmed, S., Fatema-Tuj-zohra, Choudhury, T. R., Alam, M. Z. & Nurnabi, M. Adsorption of Cu(II) and Cd(II) with graphene based adsorbent: adsorption kinetics, isotherm and thermodynamic studies. Desalin. Water Treat. 285, 167–179 (2023).

Cyril, N., George, J. B., Joseph, L. & Sylas, V. P. Catalytic degradation of Methyl orange and selective sensing of mercury ion in aqueous solutions using green synthesized silver nanoparticles from the seeds of Derris trifoliata. J. Clust Sci. 30 (2), 459–468 (2019).

Mikhaylov, P. A. et al. Synthesis and characterization of polyethylene terephthalate-reduced graphene oxide composites. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng 693 (1), 012036 (2019).

Al Faruque, M. A. et al. Graphene oxide incorporated waste wool/pan hybrid fibres. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1–12 (2021).

Karami, K., Beram, S. M., Siadatnasab, F., Bayat, P. & Ramezanpour, A. An investigation on MIL-101 fe/pani/pd nanohybrid as a novel photocatalyst based on MIL-101(Fe) metal–organic frameworks removing methylene blue dye. J. Mol. Struct. 1231, 130007 (2021).

Beiranvand, M., Farhadi, S. & Mohammadi-Gholami, A. Adsorptive removal of Tetracycline and Ciprofloxacin drugs from water by using a magnetic rod-like hydroxyapatite and MIL-101(Fe) metal-organic framework nanocomposite. RSC Adv. 12 (53), 34438–34453 (2022).

Fattahi, M. et al. Boosting the adsorptive and photocatalytic performance of MIL-101(Fe) against methylene blue dye through a thermal post-synthesis modification. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 1–13 (2023).

Alarifi, I. M., Alharbi, A., Khan, W. S., Swindle, A. & Asmatulu, R. Thermal, electrical and surface hydrophobic properties of electrospun polyacrylonitrile nanofibers for structural health monitoring. Materials 8 (10), 7017–7031 (2015).

Jamali, M. & Akbari, A. Facile fabrication of magnetic Chitosan hydrogel beads and modified by interfacial polymerization method and study of adsorption of cationic/anionic dyes from aqueous solution. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9 (3), 105175 (2021).

Mosaffa, E. et al. Enhanced adsorption removal of Levofloxacin using antibacterial LDH-biochar cross-linked chitosan/pva beads through batch and column approaches; comprehensive isothermal and kinetic study. Desalination 599, 118452 (2025).

Birniwa, A. H., Ali, U., Jahun, B. M., Al-dhawi, S. & Jagaba, A. H. B. N. Cobalt oxide doped polyaniline composites for Methyl orange adsorption: optimization through response surface methodology. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng 9, 100553 (2024).

Rose, P. K., Kumar, R., Kumar, R., Kumar, M. & Sharma, P. Congo red dye adsorption onto cationic amino-modified walnut shell: characterization, RSM optimization, isotherms, kinetics, and mechanism studies. Groundw Sustain. Dev 21, 100931 (2023).

Hemdan, S. S. The dependence of acid-base equilibria and acidity constants of congo red in buffer solutions on the ionic strength. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 59 (3), 505–512 (2024).

Vo, Q. V., Truong-Le, B. T., Hoa, N. T. & Mechler, A. The degradation of Methyl orange by OH radicals in aqueous environments: A DFT study on the mechanism, kinetics, temperature and pH effects. J. Mol. Struct. 1323, 140631 (2025).

Khodayari, P., Jalilian, N., Ebrahimzadeh, H. & Amini, S. Trace-level monitoring of anti-cancer drug residues in wastewater and biological samples by thin-film solid-phase micro-extraction using electrospun polyfam/Co-MOF-74 composite nanofibers prior to liquid chromatography analysis. J. Chromatogr. A. 1655, 462484 (2021).

Asghari, Z., Sereshti, H., Soltani, S. & Rashidi Nodeh, H. Hossein Shojaee aliabadi, M. Alginate aerogel beads doped with a polymeric deep eutectic solvent for green solid-phase Microextraction of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in coffee samples. Microchem J. 181, 107729 (2022).

Karim, S., Ahmad, N., Hussain, D., Mok, Y. S. & Siddiqui, G. U. Active removal of anionic Azo dyes (MO, CR, EBT) from aqueous solution by potential adsorptive capacity of zinc oxide quantum Dots. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 97 (8), 2087–2097 (2022).

Paredes-Laverde, M. et al. Understanding the removal of an anionic dye in textile wastewaters by adsorption on ZnCl2activated carbons from rice and coffee husk wastes: A combined experimental and theoretical study. J Environ. Chem. Eng 9 (4), 105685 (2021).

Esvandi, Z., Foroutan, R., Peighambardoust, S. J., Akbari, A. & Ramavandi, B. Uptake of anionic and cationic dyes from water using natural clay and clay/starch/MnFe2O4 magnetic nanocomposite. Surf. Interfaces. 21, 100754 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Fabrication of highly crystalline covalent organic framework for solid-phase extraction of three dyes from food and water samples. J. Sep. Sci 46 (6), 2200996 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. A novel hydroxyl-riched covalent organic framework as an advanced adsorbent for the adsorption of anionic Azo dyes. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1227, 340329 (2022).

Hashemi, S. H., Kaykhaii, M., Jamali Keikha, A. & Mirmoradzehi, E. Box-Behnken design optimization of pipette tip solid phase extraction for Methyl orange and acid red determination by spectrophotometry in seawater samples using graphite based magnetic NiFe 2 O 4 decorated exfoliated as sorbent. Spectrochim Acta - Part. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 213, 218–227 (2019).

Hashemi, S. H., Kaykhaii, M., Jamali Keikha, A. & Parkaz, A. Application of response surface methodology to optimize pipette tip micro-solid phase extraction of dyes from seawater by molecularly imprinted polymer and their determination by HPLC. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 16 (12), 2613–2627 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to Shahid Beheshti University for its financial support through the research grants.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Parisa Khodayari: Ideas, Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Validation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Review & editing, Software, Visualization, Resources. Reyhaneh Aziziyan: Validation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Review & editing, Software, Visualization, Resources. Homeira Ebrahimzadeh: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Review & editing, Methodology, Resources. Arshia Hejazi: Formal analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note